Mini Review

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Tinea Infections: Changing Face or Neglected?

*Corresponding author: Atzori Laura, Dermatology Clinic, Department of Medical Science and Public Health, University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy.

Received: August 05, 2019 Published: August 12, 2019

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.04.000820

Abstract

Dermatophyte infections are of great importance in dermatology practice. The general impression from the literature retrieval is that we are experiencing a change in tinea infections, and these changes involves epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and therapies. The question is whether dermatophytes are changing their biological attitude or there is a tendency to neglect the diagnosis, because of the common use of topical mixed antibiotic/antimycotic corticosteroid cream, delaying the assessment until no response and evident worsening. Following short review encompass actual knowledge to provide matter of tough and auspicate generation of new studies. The menace of antifungal resistance is worth global alert and address the need of reporting and execution of antifungal sensitity tests, which is not a routinely procedure. The adoption of innovative diagnostic techniques, such as MALDI-TOF and PCR identification are by the way, nevertheless, a trained dermatologist should first of all suspect the infection, even when clinical presentation is not obvious, and possibly perform a simple direct mycological examination after KHO clarification, which rapidly confirms the diagnosis. The use of combined steroidal topical drugs should be avoided, further altering the clinical presentation, sometimes giving the false impression of temporary healing, and favoring patient’s intermittent self-application, with consequent risk of side effects, including skin atrophy. Development of new antifungal and clinical trials realization is a sore point, for the apparently limited interest of pharma industry in respect to the biologics and biosimilars indications. Timing and dosage revisiting of old drugs is the current research topic. Main field of therapeutic interest is implementation of onychomycosis treatment.

Keywords: Dermatophyte Infections; Tinea Incognita; Diagnosis; Treatment; MALDI-TOF, PCR Fungal Identification

Abbreviation: KHO: Potassium Hydroxide; MALDI-TOF: Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; PDT: Photodynamic Therapy

Introduction

Experienced dermatologists rarely misdiagnose dermatophytes infections, but there is an increasing reporting of atypical extensive presentations, often after incongruous treatments, caused by emerging species, and eventually resistant to antimycotic therapy. New diagnostic tools, such as MALDI-TOF identification are expensive, and not always at disposal in daily practice, while a simple direct microscopic examination unravels the diagnosis in few minutes. Specific training should be provided to keep this area of expertise in the dermatologist’s hands.

Introduction

Superficial fungal infections are common worldwide and are of great importance in dermatology practice. The prevailing causes of these infections are dermatophytes, which can lead to a variety of clinical manifestations, such as tinea corporis, cruris, capitis, pedis and unguium [1]. Occasionally dermatophyte infections overcome the not-leaving layers of the epidermis, whose parasitism is well tolerated, with very mild inflammatory reaction and reach the dermis, usually through hair follicle parasitism. At that point, immune defenses arouse a persistent subcutaneous inflammation, with acute forms called Kerium and chronic forms, such as Majocchi’s granuloma [2]. Studies from different geographical areas show a dermatophytic infections prevalence variable from 8-10% [Croatia, Greece, Japan], up to 18-19% [Poland or Iran] [3-7].

Materials and Methods

A systematic literature search was performed on the database PubMed, from 2004 to 2019, using the keywords tinea infections and filtering for reviews and clinical trials in humans. From 612 titles, 296 were reviewed, and 154 were clinical trials. Critical revision of the contents was performed by all authors and generate the following discussing points to improve health management of dermatophyte infections including reductions in morbidity, as well as providing arguments to generate new drug and clinical trials in this neglected field of research.

How has Changed EpidemiologyEpidermophyton floccosum, Microsporum audouinii and Trichophyton schoenleinii acted as the major pathogens of superficial fungal diseases 100 years ago, but their frequency decreased since the middle of the twentieth century; meanwhile, there has been an increased isolation of Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton interdigitale, Trichophyton tonsurans and Microsporum canis, and these fungi have become the major species globally [8].

At present, Trichophyton rubrum is the most common cause of tinea cruris and tinea pedis, followed by Epidermophyton floccosum and Trichophyton interdigitale [formerly T. mentagrophytes]. Furthermore, a recent Japanese study showed that Trichophyton mentagrophytes has a higher spreading rate among tinea pedis in young adults and adults, whereas Trichophyton rubrum shows a higher spreading rate among the elderly [9].

Regarding etiology of tinea corporis, Trichophyton rubrum is the most common cause. Other notable causes of tinea corporis include Trycophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Tricophyton interdigitale, Microsporum gypseum, Tricophyton violaceum and Microsporum audouinii. Tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton Tonsurans in adults may result from a contact with a child with tinea capitis [10]. However, in some countries there has been observed a growing spreading rate of Tricophyton verrucosum as cause of tinea corporis. In fact, a Tunisian retrospective study showed an increased frequency of isolated T. verrucosum passing from one case in 1998 to 37 cases in 2010 [11].

In the last years, a significant increase in incidence and clinical changes of tinea capitis has been reported [12]. For example, in Croatia, frequency of tinea capitis due to Microsporum spp ranged from 1 case in year 1978 to 328 cases in 2008 [13]. Microsporum spp, especially Microsporum canis, presents as the predominant tinea capitis responsible worldwide, including Mediterranean and central Europe. However, in North America and United Kingdom, Tricophyton tonsurans has replaced Microsporum canis as the most common causative organism of tinea capitis, accounting 50-90% of cases in UK, while Tricophyton violaceum represents the major specie in Greece and Belgium [14-16]. Microsporum audouinii and Tricophyton soudanense are primary causes of tinea capitis in West Africa [17-18], while Tricophyton verrucosum is a common cause of tinea capitis in Turkey [13]. An increase in dermatophyte scalp infections caused by African species is reported in countries receiving African immigrants, including Canada. In fact, a recent retrospective Canadian study reported that, in Montreal, the number of tinea capitis caused by African species of dermatophytes increased six-fold over 17 years, affecting mostly African immigrant children (84%) [19].

In the last years, a significant increase in incidence and clinical changes of tinea capitis has been reported [12]. For example, in Croatia, frequency of tinea capitis due to Microsporum spp ranged from 1 case in year 1978 to 328 cases in 2008 [13]. Microsporum spp, especially Microsporum canis, presents as the predominant tinea capitis responsible worldwide, including Mediterranean and central Europe. However, in North America and United Kingdom, Tricophyton tonsurans has replaced Microsporum canis as the most common causative organism of tinea capitis, accounting 50-90% of cases in UK, while Tricophyton violaceum represents the major specie in Greece and Belgium [14-16]. Microsporum audouinii and Tricophyton soudanense are primary causes of tinea capitis in West Africa [17,18], while Tricophyton verrucosum is a common cause of tinea capitis in Turkey [13]. An increase in dermatophyte scalp infections caused by African species is reported in countries receiving African immigrants, including Canada. In fact, a recent retrospective Canadian study reported that, in Montreal, the number of tinea capitis caused by African species of dermatophytes increased six-fold over 17 years, affecting mostly African immigrant children (84%) [19].

Recently, it has been described a case of inflammatory tinea capitis due to Microsporum Gypseum in a Spanish 6-years-old child [20]. Tinea capitis caused by Microsporum Gypseum is a very rare condition, especially in Europe, without new cases since 2000. Sporadic cases have been described in Brasil [21], Mexico [22] and Japan [23]. Tinea capitis is a typical manifestation in prepubertal children, thus the increased observation in adults and elderly patients is an emerging condition [13,24]. While no significant gender predilection or slight male prevalence is reported in children [16,17,25-27], tinea capitis in adolescents and adulthoods involves more frequently female patients, with a ratio ranging from 3:1 to 6:1 [28-30].

How has Changed Clinical Presentation

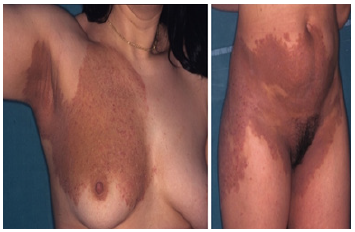

Figure 1: A young lady with longstanding diffuse dermatophyte infection, treated for rosacea and psoriasis. Careful examination pointed out also hand and foot onychomycosis.

A diagnosis of superficial fungal infection may be suspected based upon clinical features, but many cutaneous disorders can present with similar appearance, making differential diagnosis difficult. In the presence of the typical ring-warm pattern, characterized by an erythematous scaling annular lesions, that moves centripetally with central clearing, the diagnosis is very simple, and general practitioner probably detect and correctly treat the majority of cases. Dermatologic consulting takes over the worsening cases, already extensive and often inflammatory, misdiagnosed for rosacea, psoriasis, contact dermatitis (Figure 1 and 2), but also lupus erythematosus, zoster infection, seborrheic dermatitis. Variations in clinical presentation depend on different conditions, combining the pathogen invasiveness and the host response, such as the age of the patient, obesity, and immune status [31-34].

Figure 2: A 24-year-old girl presenting to the Dermatology Clinic to perform patch test, being diagnosed a contact dermatitis, resistant to systemic and topical treatment.

Sometimes the seek for medical care is postponed by the patients, because of the very mild inflammatory host response to the pathogen and its metabolic products is well tolerated or controlled by the self-administration of over-the count products. Especially anthropophilic species such as T. rubrum can inhibit the immune response, and favor long-standing infections [35, 36]. General treatment with immunosuppressant is among major predisposing factors, and sometimes dermatophytes super-infect an underlining skin disease, simulating a sudden worsening which requires immune suppressant dosage increase, such as in pemphigus (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A 56-year-old lady affected with pemphigus vulgaris, with sudden diffuse worsening, resistant to immunosuppressant treatment at high dosage. Direct mycological examination rapidly solved the quandary.

Nevertheless, the most frequent cause of clinical appearance alteration is topical corticosteroid mistreatment, causing a condition called tinea incognito, which is also used interchangeably with the term “steroid-modified tinea”. The term tinea incognito is actually not correct because of the Latin etymology of the term, which literally means “unknown”. In fact, according to Latin grammar, the adjective must reflect the same gender of the name “tinea”, which is female, so the correct term should be tinea incognita [37,38]. Tinea incognita is a dermatophytosis with atypical features [like the absence of the “classic” ringworm] and it can present with different clinical appearances, including lichenoid, rosacea-like, eczema-like and psoriasis-like [39,40].

The abuse of topical steroids in the treatment of tinea lesions, especially in African and other developing countries, creates a large pool of mistreated patients who are a constant source of infection 41. Steroid alone or used in combination with antibiotic, antimycotic, vitamin D derivatives, may therefore contribute to treatment failure and may expose the patient to a risk of side effects like teleangectasia and skin atrophy [42,43]. Recently, other incongruous topical treatment such as acyclovir, tacrolimus, and pimecrolimus, have been reported as responsible for tinea incognita [44,47].

However, it is important to underline that topical steroids do modify the clinical morphology of tinea but do not necessarily make the disease difficult to recognize 38. Lesions are asymmetrical or homolateral, with a defined progression border, which do not escape to the eye of an experienced dermatologist. Of course, a certain training is necessary. In some cases, disease presentation may be difficult to diagnose from the very beginning, due to intrinsic variations of the pathologic process. In a personal experience, 30% of misdiagnosed cases were not previously treated with steroids 43. Certain variations are highly conditioned by the site of involvement, with tinea faciei among the most misleading presentation, probably conditioned by frequent washing, use of moisturizing, and sun exposure [43-46].

In other experience, tinea corporis [52] is among the most misleading presentation, not necessarily related with topical steroids exposure. The term “tinea atypica” was proposed to better define the numerous clinical variables conditioning unusual dermatophyte infection features, both from primary and iatrogenous predisposing factors [40-53]. Independently from site of involvement, tinea atypica usually presents with more severe inflammatory components, with less defined borders, central scaling and/or follicular papules, vesicle-pustules instead of clearing, and sometimes with oedematous indurations. Hyperpigmentation and crusting secondary to itching are also frequent (Figure 2).

Many case collection report atypical, misleading presentation, also in newborns [51-60]. Palmo-plantar regions are sometimes affected with vesicle-bullous lesions [56-60]. Fungal scalp infections are expected to show non-inflammatory lesions, main symptoms seeking for medical consulting being a persistent pruritus, thus noting the pseudo-alopecic patches with black dots or few millimeters cut from the follicle hairs [14]. However, a growing number of very inflammatory tinea capitis cases, clinically characterized by a tumor mass covered with thick crusts [known as Kerion Celsi] caused by Microsporum canis and Microsporum gypseum have been registered [16-18]. For example, in Croatia, 58 cases of Kerion Celsi were reported in the last 8 years, due to Microsporm spp instead of t. mentagrophytes, which was the usual expected pathogen [12].

Substantially, recent literature pointed out atypical presentation might be an emerging problem [43-65]. In our dermatology unit, between 1990 and 2009, 154 cases of atypical tinea were diagnosed (71 male/83 female, 2–81 years old), with a median of 7.7 cases/year, representing 2.5% of all the dermatophyte infections diagnosed every year [43]. As regards isolates, in Europe [66-67] the responsible dermatophytes in order of frequency were: Microsporum canis, Trichophyton rubrum, Tricophyton mentagrophytes var. mentagrophytes, Tricophyton mentagrophytes var. interdigitalis, Microsporum gypseum, Epidermophyton floccosum, and Tricophyton verrucosum. Another similar study made in Iran, based on 56 patients showed a different trend, with prevalence of Tricophyton Verrucosum (35% of cases) followed by Tricophyton Schoenleinii (20%) as primary cause of tinea atypica [52], while in India the most involved dermatophyte was Tricophyton rubrum followed by Tricophyton Mentagrophytes [68].

How has Changed Diagnosis

The conventional procedure used to diagnose a dermatophyte infection is direct microscopic observation after potassium hydroxide [KOH] clarification of skin, hair or nail sampling [69]. Main limitation of this very simple procedure is that microscopy is not directly available in many private and even public offices. Probably, less dermatologists and sometimes laboratory physicians are trained to recognize dermatophytes. Species identification by fungal culture is very rarely performed, because it is often negative for contamination, and time-consuming.

In the last years, a new assay based on matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight [MALDI-TOF] has been developed to ensure a rapid and economic laboratory method of fungi identification [70-73]. The MALDI-TOF MS technology, from several years experienced for bacterial identification, has been implemented to directly detects the molecular weights of the phenotypical proteins from the cultured microorganisms without preselection and purification steps, and it is now applied to fungal identification. The advantages of this assay consist of independency from operator expertise, providing rapid results with accuracy comparable to DNA sequencing. However, filamentous fungi identification has deserved certain technical difficulties, and remains particularly challenging, partly due to the lack of clear species definition for some taxa [71,72].

Moreover, a review of the ten studies published between 2008 and 2015 showed that the accuracy of MALDI-TOF MS-based for dermatophyte identification varied between 13.5 and 100 %. This variability was probably due to lack of standardizations in laboratory process [72]. Recently, the PCR based detection has offered significant advances in fungal species identification, with a potential increase in the speed of diagnosis, allowing identification in 1 day [15,74,75]. Identification of fungi in dermatological samples using PCR provides better results in comparison with cultures, leading to dermatophyte identification while cultures gave negative results. However, the benefits obtained with the use of PCR methods must be put in balance with the costs of molecular biology equipment [74].

In extensive dermatophyte infections or in unclear cases, it may be necessary to perform a skin biopsy for histological analysis, in order to exclude other causes of dermatitis, and assess direct fungal responsibility rather than superinfection [43]. The pathologist should be advised of the clinical diagnostic suspect, to perform special stain, such as periodic acid-Schiff, not to miss the hyphae in the stratum corneum.

How would Change Treatment

Antifungals agents have revolutionized the natural course of the Dermatophyte infections in the last century, with a wide spectrum of oral and topical drugs, whose choice depends on the extent, site of infection and causative organism [76,77]. Most superficial cutaneous dermatophyte infections can be managed with topical agents such as azoles, allylamines, butenafine, ciclopirox and tolnaftate [78,79]. Special lacquers are at disposal to increase penetration into the ungual lamina. Oral treatment with drugs such as terbinafine, itraconazole, fluconazole and griseofulvin is used for extensive or refractory cutaneous infections and every time the infection extends into follicles or nails, which are major sources of persistent infections [80]. The use of combinations therapies, such as azoles with steroids cream is discouraged, although rapidly effective on inflammatory forms and itching, because it is frequently associated with treatment failure, partly due to discontinuation before complete cure, as well as chronic self-prescription with the risk of corticosteroid-induced skin atrophy development [79,80].

However, in the last decade, a growing epidemic trend of recurrent and chronic dermatophytosis has been reported, claiming for newer antifungal agents and more effective strategies. A diagnosis of chronic dermatophyte infection must be considered in patients with disease duration of more than 6 months, with or without recurrence, despite being treated with adequate antifungal drugs. Recurrent dermatophytosis is instead defined as occurrence of infection within few weeks after discontinuation of the antimycotic treatment [81]. These conditions question the possibility that dermatophyte strains resistant to the treatment are emerging. It is difficult to address this question, because few laboratories perform antifungal sensibility tests in daily practice, thus we do not have much evidence of antifungal resistance development, as it is for aspergillus and candida spp. infections [82]. In a very recent study, terbinafine resistance was reported for E. floccosum and two Trichophyton species, i.e., T. rubrum and T. tonsurans [83].

Current limitation of antifungal drugs is the overlapping mechanisms of action, with same cellular targets, which may contribute to the multidrug resistance observed for several dermatophyte: these mechanisms involve the overexpression of efflux pumps or detoxification enzymes, along with target and drug modification [84-87].

Moreover, patients often neglect and abandon treatment, due to its required long-term assumption and side effects, causing a treatment failure [84]. For all these reasons, in the last decade research has investigated newer formulations or derivatives of existing drugs as well as newer antifungal active principles, which are under clinical trials [86]. Especially synthetic drugs acting as metabolic pathways inhibitor are promising pipelines, because of the multiple cellular targets to be exploited: from glyoxylate cycle, to pyrimidine biosynthesis, cytochrome P450 pathway, iron metabolism, acetate metabolism and heme biosynthesis, along with signal transduction pathways, such as mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and calcium signaling pathways, as well as transcription factor, DNA-binding and histone deacetylase inhibitors [87]. Alternative approaches include physical intervention, such as the use of Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) and lasers, whose preliminary clinical trials suggest interesting results, but require further studies [88].

Judicious use of antifungals, emphasizing patient compliance and avoiding combined prescription of topical corticosteroids are necessary conditions to cure patients presenting with difficult to treat dermatophytosis. Furthermore, improving hygiene of the skin, nails, and hair, avoidance of humidity and occlusive clothing represent important measures to control the infection burden.

Conclusion

Beside the lack of systematic epidemiologic studies, it is important to recognize dermatophytosis, which are very spread and sometimes neglected. Modification of human floras along with geography and socio-economic conditions are to be carefully surveyed by the medical community. Migration, changing the lifestyle, auto medication, misdiagnosis, all these factors could change the clinical aspect, the type of fungi or the sensitivity to antifungal agents. The general impression from recent literature is that new pathogens and atypical dermatophyte infections are increasing worldwide, with very extensive and inflammatory presentations, late diagnosis, incongruous treatment and even possible resistance to treatment. Sometimes, chronic evolution could lead us to look for systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, but also congenital and acquired immune disorders.

In the era of over-investigations, this diagnostic of dermatophyte infections can often be made on the clinical presentation, and simple direct mycological examination, but innovative diagnostic techniques and new therapies have been recently provided. The main role of the dermatologist is not only to recognize and choose the right dermatomycosis treatment, but also to address the infection burden, detecting the possible causes and challenge to be covered. Finally, all physicians should be aware of these changes in order to provide healthier population in every environment.

References

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M (2014) Diagnosis and management of Tinea Infections. Am Fam Physician 90: 702-710.

- Bressan AL, Silva RS, Fonseca JC, Alves Mde F (2011) Majocchi’s Granuloma. An Bras Dermatol 86: 797-798.

- Kaštelan M, Utješinović-Gudelj V, Prpić-Massari L, Brajac I (2014) Dermatophyte Infections in Primorsko-Goranska County, Croatia: a 21-year Survey. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 22(3): 175-179.

- Maraki S, Mavromanolaki VE (2016) Epidemiology of Dermatophytoses in Crete, Greece. Med Mycol J 57: E69-E75.

- Sei Y (2015) Epidemiological Survey of Dermatomycoses in Japan. Med Mycol J 56(4): J129-J135.

- Budak A, Bogusz B, Tokarczyk M, Trojanowska D (2013) Dermatophytes isolated from superficial fungal infections in Krakow, Poland, between 1995 and 2010. Mycoses 56(4): 422-428.

- Zamani S, Sadeghi G, Yazdinia F, Moosa H, Pazooki A, et al. (2016) Epidemiological trends of dermatophytosis in Tehran, Iran: A five-year retrospective study. J Mycol Med 26(4): 351-358.

- Zhan P, Liu W (2017) The Changing Face of Dermatophytic Infections Worldwide. Mycopathologia 182(1-2): 77-86.

- Suzuki S, Mano Y, Furuya N, Fujitani K (2017) Epidemiological Study on Trichophyton Disseminating from the Feet of the Elderly. Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi 72(3): 177-183.

- Néji S, Makni F, Cheikrouhou F, Sellami H, Trabelsi H, (2011) Dermatomycosis due to Trichophyton verrucosum in Sfax-Tunisia. J Mycol Med 21(3): 198-201.

- Celić D, Rados J, Skerlev M, Dobrić I (2005) What do we really know about “tinea incognita”? Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 13(1): 17-21.

- Skerlev M, Miklic P (2010) The changing face of Microsporum spp infections. Clin Dermatol 28(2): 146-150.

- Ginter-Hanselmayer G, Weger W, Ilkit M, Smolle J (2007) Epidemiology of tinea capitis in Europe: current state and changing patterns. Mycoses 50(2): 6-13.

- Gupta AK, Summerbell RC (2000) Tinea Capitis. Med Mycol 38(4): 255-287.

- Fuller LC (2009) Changing face of tinea capitis in Europe. Curr Opin Infect Dis 22(2): 115-118.

- Emele FE, Oyeka CA (2008) Tinea capitis among primary school children in Anambra state of Nigeria. Mycoses 51(6): 536-541.

- Fulgence KK, Abibatou K, Vincent D, et al. (2013) Tinea capitis in schoolchildren in southern Ivory Coast. Int J Dermatol 52: 456.

- Kelly BP (2012) Superficial fungal infections. Pediatr Rev 33: e22.

- Marcoux D, Dang J, Auguste H, McCuaig C, Powell J, et al. (2018) Emergence of African species of dermatophytes in tinea capitis: A 17‐year experience in a Montreal pediatric hospital. Pediatr Dermatol 35(3): 323-328.

- García-Agudo L. Espinosa-Ruiz JL (2018) Tiña capitis por Microsporum gypseum, una especie infrecuente. Arch Argent Pediatr 116(2): e296-e299.

- Brilhante RS, Cordeiro RA, Rocha MF, et al. (2004) Tinea capitis in a dermatology center in the city of Fortaleza, Brazil: the role of Trichophyton tonsurans. Int J Dermatol 43(8): 575-579.

- Arenas R (2002) Dermatofitosis en México. Rev Iberoam Micol 19: 63- 67.

- Haga R, Susuki H (2002) Tinea capitis due to Microsporum gypseum. Eur J Dermatol 12: 367-368.

- Lipozencić J, Skerlev M, Pasić A (2002) An overview: the changing face of cutaneous infections and infestations. Clin Dermatol 20: 104-108.

- Mirmirani P, Tucker LY (2013) Epidemiologic trends in pediatric tinea capitis: a population-based study from Kaiser Permanente Northern California. J Am Acad Dermatol 69(6): 916-921.

- Mapelli ET, Cerri A, Bombonato C, Menni S (2013) Tinea capitis in the paediatric population in Milan, Italy: the emergence of Trichophyton violaceum. Mycopathologia 176(3-4):243-246.

- Zampella JG, Kwatra SG, Blanck J, Cohen B (2017) Tinea in Tots: Cases and Literature Review of Oral Antifungal Treatment of Tinea Capitis in Children under 2 Years of Age. J Pediatr 183: 12-18.

- Zhan P, Geng C, Li Z, Li D, Liu W et al. (2015) Evolution of tinea capitis in the Nanchang area, Southern China: a 50-year survey (1965-2014). Mycoses 58(2): 261-266.

- Rebollo N, Lòpez-Barcenas AP, Arenas R (2008) Tinea capitis. Actas Dermosifilogr 99: 91-100.

- Frangoulis E, Papadogeorgakis H, Athanasopoulou B, Katsambas A (2005) Superficial Mycoses due to Tricophyton violaceum in Athens, Greece: a 15-year retrospective study. Mycoses 48(6): 425-429.

- Shiraki Ogawa Y (2010) Role of cytokine secretion of human keratinocytes in dermatophytosis. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi 51: 125-130.

- Wagner DK, Sohnle PG (1995) Cutaneous defenses against dermatophytes and yeasts. Clin Microbiol Rev 8(3): 317-335.

- Dahl MV (1993) Suppression of immunity and inflammation by products produced by dermatophytes. J Am Acad Dermatol 28(5): S19-S23.

- Jones HE (1986) Cell-mediated immunity in the immunopathogenesis of dermatophytosis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 121: 73-83.

- Leibovici V, Evron R, Axelrod O, Westerman M, Shalit M, et al. (1995) Imbalance of immune responses in patients with chronic and widespread fungal skin infection. Clin Exp Dermatol 20(5): 390-394.

- Dahl MV, Grando SA (1994) Chronic dermatophytosis: what is special about Trichophyton rubrum? Adv Dermatol 9: 97-109.

- Holubar K, Male O (2002) Tinea incognita vs. tinea incognito. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 10: 39.

- Verma SB (2017) A closer look at the term “tinea incognito”: a factual as well as grammatical inaccuracy. Indian J Dermatol 62: 219-220.

- Gorani A, Schiera A, Oriani A (2002) Case report. Rosacea-like Tinea incognito. Mycoses 45: 135-137.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N (2013) Tinea atypica. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 148(3): 593-601.

- Bishnoi A, Vinay K, Dogra S (2018) Emergence of recalcitrant dermatophytosis in India. Lancet Infect Dis 18: 250-251.

- Verma SB, Vasani R (2016) Male genital dermatophytosis-clinical features and the effects of the misuse of topical steroids and steroid combinations-an alarming problem in India. Mycoses 59(10): 606-614.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N, Aste N (2012) Dermatophyte infections mimicking other skin diseases: a 154-person case survey of tinea atypical in the district of Cagliari (Italy). Int J Dermatol 51(4): 410-415.

- Aste N, Pau M, Aste N, Atzori L (2011) Tinea corporis mimicking herpes zoster. Mycoses 54: 463-465.

- Siddaiah N, Erickson A, Miller G, Elston DN (2004) Tacrolimus-induced tinea incognito. Cutis 73(4): 237-238.

- Crawfford KM, Bostrom P, Russ B, Boyd J (2004) Pimecrolimus-induced tinea incognito. Skinmed 3(6): 352-353.

- Rallis E, Koumontaki-Mathioudaki E (2008) Pimecrolimus induced tinea incognito masqueranding as intertriginous psoriasis. Mycoses 51: 71- 73.

- Nicola A, Laura A, Natalia A, Monica P (2010) A 20-year survey of tinea faciei. Mycoses. 53(6): 504-508.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JG, Camacho F (1992) Tinea faciei: étude epidemiologique. Ann Dermatol Venereol 119(2): 101-104.

- Meymandi S, Wiseman MC, Crawford RJ (2003) Tinea faciei mimicking cutaneous lupus erythematous: a histopathologic case report. J Am Acad Dermatol 48(2): S7-S8.

- Alteras I, Sandbanyk M, David M, Segal R (1983) Fifteen-year survey of tinea faciei in adult. Dermatologica 177(2): 65-69.

- Ansar A, Farshchian M, Nazeri H, Ghiasian SA (2011) Clinicepidemiological and mycological aspects of tinea incognito in Iran: A 16- year study. Med Mycol J 52(1): 25-32.

- Zisova LG, Dobrev HP, Tchernev G, Semkova K, Aliman AA, et al. (2013) Tinea atypica: report of nine cases. Wien Med Wochenschr 163(23-24): 549-555.

- Serarslan G (2007) Pustular psoriasis-like tinea incognito due to Trichophyton rubrum. Mycoses 50(6): 523-524.

- Romano C, Maritati E, Gianni C (2006) Tinea incognito in Italy: a 15-year survey. Mycoses 49(5): 383-387.

- Canavan TN, Elewski BE (2015) Identifying Signs of Tinea Pedis: A Key to Understanding Clinical Variables. J Drugs Dermatol 14(10): s42-s47.

- Ghislanzoni M (2008) Tinea incognito due to Trichophyton rubrum responsive to topical therapy with isoconazole plus corticosteroid cream. Mycoses 51(4): 39-41.

- Nenoff P, Mügge C, Hermann J, Keller U (2007) Tinea faciei incognito due to Trichophyton rubrum as a result of autoinoculation from onychomycosis. Mycoses 50(2): 20-25.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N (2003) Erytema multiforme IDI reaction in atypical dermatophytosis: case report. JEADV 17(6): 699-701.

- Virgili A, Corazza M, Zampino MR (1993) Atypical features of tinea in newborns. Pediatr Dermatol 10: 92-93.

- Aste N, Pau M, Aste N (2005) Tinea manuum bullosa. Mycoses. 48(1): 80-81.

- Tchernev G, Terziev I (2018) Bullous Tinea Incognito in a Bulgarian Child: First description in the Medical Literature! Open Access Maced J Med Sci 6(2): 376-377.

- Romano C, Rubegni P, Ghilardi A, Fimiani M (2006) A case of bullous tinea pedis with dermatophytid reaction caused by Trichophyton violaceum. Mycoses 49(3): 249-250.

- Neri I, Piraccini BM, Guareschi E, Patrizi A (2004) Bullous tinea pedis in two children. Mycoses 47: 475-478.

- El-Segini Y, Schill WB, Weyers W (2002) Case Report. Bullous tinea pedis in an elderly man. Mycoses 45(9-10): 428-430.

- Dolenc-Voljc M (2005) Dermatophyte infections in the Ljubljana region, Slovenia, 1995-2002. Mycoses 48(3): 181-186.

- Segundo C, Martınez A, Arenas R, Fernández R, Cervantes RA (2004) Superficial infections caused by Microsporum canis in humans and animals. Rev Iberoam Micol 21(1): 39-41.

- Durra B, Rasul ES, Boro B (2017) Cinico-epidemiological study of tinea incognito with microbiological correlation. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 83(3): 326-331.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste N (2015) Mycological Examination. In: Katsambas A, et al. (Eds) European Handbook of Dermatological Treatments. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany. 1245-1267.

- Nenoff P, Erhard M, Simon JC, Muylowa GK, Herrmann J, Rataj W, et al. (2013) MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry - a rapid method for the identification of dermatophyte species. Med Mycol 51(1): 17-24.

- Kallow W, Erhard M, Shah H, Raptakis E, Welker M (2010) MALDI-TOF MS for microbial identification: years of experimental development to an established protocol. In: Shah H, et al. (Eds) Mass Spectrometry for Microbial Proteomics 1st Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 255-276.

- L’Ollivier C, Ranque S (2017) MALDI-TOF-Based Dermatophyte Identification. Mycopathologia 182(1-2): 183-192.

- Gräser Y, Monod M, Bouchara JP, Dukik K, Nenoff P, et al. (2018) New insights in dermatophyte research. Medical Mycology 56: S2-S9.

- Sharma R (2017) A Pilot Study for the Evaluation of PCR as a Diagnostic Tool in Patients with Suspected Dermatophytoses Indian Dermatol Online J 8(3): 176-180.

- Verrier J, Monod M (2017) Diagnosis of Dermatophytosis Using Molecular Biology. Mycopathologia 182: 193-202.

- Durdu M, Ilkit M, Tamadon Y, Tolooe A, Rafati H, et al. (2017) Topical and systemic antifungals in dermatology practice. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 10(2): 225-237.

- Tsunemi Y (2016) Oral Antifungal Drugs in the Treatment of Dermatomycosis. Med Mycol J 57(2): J71-J75.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, El-Gohary M (2015) Evidence-based topical treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis: A summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Dermatol 172(3): 616-641.

- Schaller M, Friedrich M, Papini M, Pujol RM, Veraldi S (2016) Topical antifungal- corticosteroid combination therapy for the treatment of superficial mycoses: Conclusions of an expert panel meeting. Mycoses 59(6): 365-373.

- Sahni K, Singh S, Dogra S (2018) Newer Topical Treatments in Skin and Nail Dermatophyte Infections. Indian Dermatol Online J 9(3): 149-158.

- Dogra S, Uprety S (2016) The menace of chronic and recurrent dermatophytosis in India: Is the problem deeper than we perceive? Indian Dermatol Online J 7: 73.

- Arendrup MC (2014) Update on antifungal resistance in Aspergillus and Candida. Clin Microbiol Infect 20(6): 42-48.

- Salehi Z, Shams-Ghahfarokhi M, Razzaghi-Abyaneh M (2018) Antifungal drug susceptibility profile of clinically important dermatophytes and determination of point mutations in terbinafine-resistant isolates. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 37(10): 1841-1846.

- Martinez-Rossi NM, Peres NT, Rossi A (2008) Antifungal resistance mechanisms in dermatophytes. Mycopathologia 166(5-6): 369-383.

- Cowen LE, Sanglard D, Howard SJ, Rogers PD, Perlin DS (2014) Mechanisms of Antifungal Drug Resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5(7): a019752

- Pianalto KM, Alspaugh JA (2016) New Horizons in Antifungal Therapy. J Fungi (Basel) 2: E26.

- Martinez-Rossi NM, Bitencourt TA, Peres NTA, Lang EAS, Gomes EV, et al. (2018) Dermatophyte Resistance to Antifungal Drugs: Mechanisms and Prospectus. Front Microbiol 29(9): 1108.

- McCarthy MW (2017) Advances in the management of fungal infections. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 15: 837-839.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.