Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Family Needs of Critically Ill Patients in Central Jordan: A Family Perspective

*Corresponding author: Wesam Thaer Almagharbeh, Department of Nursing, AlGhad International Colleges for Applied Medical Sciences, Al Madinah Al Munawarah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Received: February 27, 2019 Published: March 08, 2019

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.01.000546

Abstract

Background and aims: Family members’ needs of hospitalized critically ill patients have been researched using both quantitative and qualitative designs. The purpose of this study was to describe family members’ perceptions of their needs during the hospitalization of their critically ill relative.

Methods: Two questionnaires were used; socio-demographic data sheet and the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory (CCFNI) questionnaire, a descriptive comparative design was utilized to describe family members’ perceptions of their needs during hospitalization of their critically ill relative.

Results: A convenience sample of 227 family members participated in the study. The sample included 57.3% family members from public hospitals and 42.7% from private hospitals. Family members perceived 27 out of 44 needs as important or very important. The family members perceived assurance, information, and proximity higher than comfort and support needs (4 out of the 10 were related to the assurance subscale, 3 were related to proximity subscale; and the remaining items were related to the information subscale).

Discussion and Conclusions: The current study investigated family needs within the context of the Jordanian population using valid and reliable measures. Although several studies investigated family needs, the current study was superlative to these by including larger samples from culturally diverse settings. Regardless of its descriptive nature, the study findings can help nurses give more attention to the psychological needs of the family members and involve these needs in their plan of care. The study has several implications for policy makers and nursing practice where fulfilling family needs is congruent with the holistic practice widely advised.

Keywords: CCFNI; Critically-ill patient; Nursing; Family needs; Jordan

Introduction

Admission to critical care is considered stressful and sometimes traumatic for both patients and their family members [1]. Peoples’ ability to cope with the emotional and psychological aspects of such admission is confronting [2]. Such an experience affects family’s stability and compromise their ability to interact and support their ill relative and subsequently affects treatment’ responses [3,4]. It is well established in the literature that family members can play several crucial roles in the critically ill patient’s plan of care [5,6]. Among the roles assuming decision-making on behalf of the patient, especially when this patient is physically or psychologically compromised by a serious illness [7] and providing social support [8]. The family context represents the most important support system that positively influences patient’s outcomes [5]. When the family responses to stressors are overwhelming, the result may be inability of the family to provide patient support hence affecting patients’ recovery [7,8].

Stressors affecting family members of critically ill patients include unfamiliar critical care environment, total shifting of the responsibilities to family members, lack of knowledge, and financial concerns related to hospitalization [9]. These stressors can generate a variety of emotional responses such as shock, anxiety, anger, fear, which can overwhelm the family unit and affect its sense of wellbeing [1,8]. Melter [10] was one of the first investigators who addressed family needs of critically ill patients. She identified 45 need statements that were ranked according to its importance. Lieske [11] further refined these needs and grouped them into five dimensions: support, information, comfort, proximity, and assurance. The dimension of support includes those behaviours that support the family during critical illness such as behaviours to reduce anxiety. The dimension of information reflects information given to the family members concerning the critically ill patient. The dimension of comfort encompasses the personal comfort needs of the family of the critically ill such as physical rest. Proximity addresses being able to be beside the patient, while the dimension of assurance reflects hope about patient outcomes.

Family members’ needs of hospitalized critically ill patients have been researched using both quantitative and qualitative designs [3,12-16]. Research on these topics has been conducted in different countries (e.g. Australia, Belgium, China, Jordan, Norway, Sweden and USA and many others) within different critical care units. In Jordan, personal obligations and responsibilities of extended family towards relatives are highly valued [12,17]. Therefore, providing support to families when a family member is ill is encouraged [16,17]. Visiting hospitalized relatives is seen as a positive social act, but it is both socially and religiously encouraged, thus becoming both a family necessity and an obligation [12,17], especially with critical and sudden/unexpected admissions. Although needs of family members have been studied in the Jordanian context, the current study targeted different geographic areas of Jordan that have not been studied before. Previous studies included smaller samples, from Northern Jordan, and/or didn’t include private hospitals [12,16,18,19].

The purpose of the study

The purpose of this study was to describe family members’ perceptions of their needs during the hospitalization of their critically ill relative. A secondary aim was to compare needs according to members’ demographics and hospital type.

Methods

Study design

A descriptive comparative design was utilized to describe family members’ perceptions of their needs during hospitalization of their critically ill relative. Two questionnaires were used; socio-demographic data sheet and the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory (CCFNI) questionnaire originally developed by Melter and Lieske [20] and translated by Omari [16]. The questionnaire was further refined by the researchers for clarity and understandability.

Setting

Five hospitals selected for this study were in Amman, the capital of Jordan. At the time of data collection, Amman encompassed a total of 37 hospitals with specialized units that provide critical care to adult patients; 30 private, 3 public and 4 military hospitals [21]. Because of approval issues, the military hospitals refused participation. The final sample included 3 private and two public hospitals. Hospitals were representative of the central region of Jordan.

Samples

The study populations consisted of family members of hospitalized critically ill patients. For the purpose of this study, a critically ill patient is any patient aged 18 years or older admitted to any critical care unit from the selected hospitals. A convenience sampling technique was used to select willing family members from the selected hospitals. The inclusion criteria included an adult family member aged 18 years or over, able to read write Arabic, had a first-degree relationship with the patient (spouse, father/ mother, son/daughter, or brother/sister), and visiting their relative within 48-72 hours of hospitalization since it was suggested to study family needs within this period [11]. Parents and other family members of paediatric patients were excluded from the study, since the family members of paediatric patients have different needs [22,23]. The sample size was calculated using a free-available statistical software package called the statistical software (G*Power version three). Estimated sample size for independent sample t-test was 64 participants. A sample size of 216 was required to achieve statistically significant relationships of moderate effect size of significant level of α = 0.05 and ß= .20. Questionnaires were completed by family members at their convenience and returned to the researchers through departments.

Ethical considerations

Prior to conducting this study, permission and approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Faculty of Graduate Studies at the University of Jordan as well as IRB from the selected hospitals. On the participant level, informed written consent was obtained from each participant. The nature of the study, its purposes, significance, and benefits were explained to the family members via detailed letter. The letter asked each participant to sign indicating his/her agreement to participate.

The Instruments

The study included the use of two instruments. First, a short socio-demographic questionnaire about family member’ age, gender, educational level, previous hospital experience, the relationship to the patient, perceived health condition of the patient and type of hospital. The second was the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory (CCFNI) questionnaire originally developed by Melter and Lieske [20] consisting of 45 need statements within 5 subscales. Internal consistency reliability for the total questionnaire using Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.88 to 0.98. Items in the CCFNI are scored on a Likert scale from (1, not important) to (4, very important) with higher scores indicating greater importance of the need being measured. The modified and translated CCFNI questionnaire to Arabic by Omari [16] was use for the purpose of this study. Permissions to use the CCFNI were obtained from the original and translating authors. A pilot test was conducted with several family members to ensure its readability and clarity. Besides, the questionnaire has been proven valid in several previous studies both in English and Arabic.

Data analysis

The Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 was used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation and percentage) were used to describe the study samples and to answer research questions. Comparative tests (t test and chi square) were used to test differences between subgroups.

Results

Socio-demographics of the family members

A convenience sample of 265 family members were invited to participate, 25 family members declined participation because they were either busy or tired. Thirteen questionnaires were eliminated because of missing data. The final family members sample was 227. All 227 family members met the inclusion criteria. The mean age of family members was 33.3 years (SD=9.1 year) ranged from 18 to 59 years. The majority was males (61.1%) and had attained high school education or greater (89.9%). More than 50 % of family members were sons and daughters. Approximately (75%) of the sample perceived the condition of the patient as serious or critical. Almost 35% of the sample had no previous experience of a relative admission. The sample included 57.3% (n=130) family members from public hospitals, and 42.7% (n=97) from private hospitals.

Family members’ perceptions of the most important needs

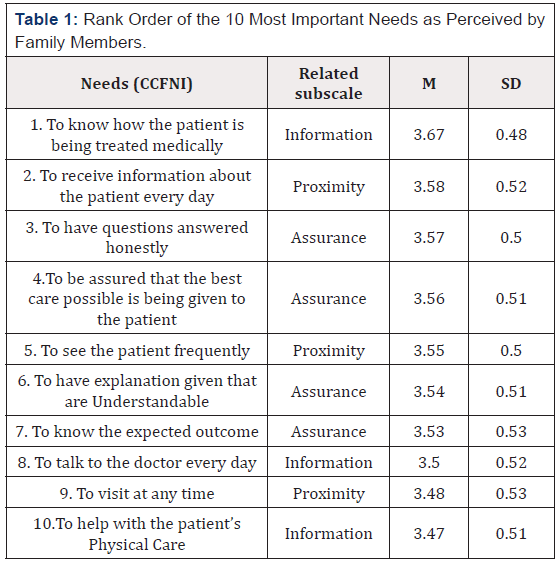

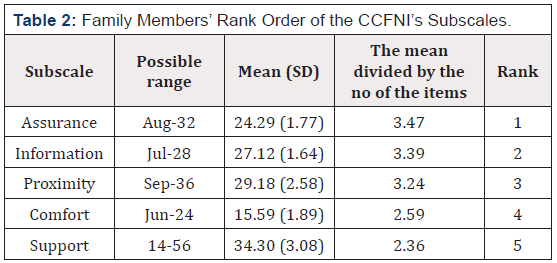

Family members perceived 27 out of 44 needs as important or very important. On the other hand, Table 1 shows the 10 most important needs as perceived by family members of critically ill patients. Four of the10 most important needs were related to the assurance subscale; “to have questions answered honestly,” “to be assured that the best care possible is being given to the patient,” “to have explanations given that are understandable,” to know the expected outcome.” Three were related to proximity subscale; “to receive information about the patient every day, ’to see the patient frequently,” “to visit at any time,” “to receive information about the patient every day.” The remaining items were related to the information subscale. None of the10 most important needs were related to support or comfort subscale. On the contrary, the 10 least important needs on the CCFNI were related to support subscale (7 out of 14 support items) and comfort subscale (3out of 6 comfort items). The three least important needs were “to have a place to be alone while in the hospital,” “to be alone at any time,” “to have good food available in the hospital.” In addition, family members perceived the subscale of assurance and information as the most important and the subscale of comfort and support as the least important (Table 2).

The relation between family members’ socio-demographics and their perception of the most important needs:

Statistical tests comparison showed no significant differences in family perceptions of most important needs based on their sociodemographics. The only significant factor to differ was hospital type (t (225) =-2.62, P<0.01) where members of private hospitals scored a mean of 25.7 (SD=3.1) and members of public hospitals scored a mean of 24.6 (SD=2.9).

Discussion

Perceptions of family needs continue to be a focus for research [3,12-14,16,24]. The current study investigated family needs within the context of the Jordanian population using CCFNI as a valid and reliable measure. Superlative to previous studies, the current study included larger sample from a culturally diverse setting including both private and public sectors where family needs expected to differ.

In this study, family members identified the most important family members’ needs that were related to assurance, information, and proximity subscales. The results were consistent with Maxwell et al., findings’ [25] where needs of assurance, information and proximity were ranked highest. These results were not consistent with Koski & Warren [26] in which needs for support, proximity and information were ranked highest by family members.

In this study, family members perceived needs for assurance as more important than other needs. Like previous studies [25,27] the heights were ‘to be assured that the best care possible is being given to the patient,’ ‘to know the expected outcomes,’ ‘to have questions answered honestly.’ One explanation may be that family members’ main concern was their psychological needs. These needs were consistent with health conditions of their relative, trusting health care providers, and assurance of receiving the best

care. Jordanian family members of critically ill patients have trust and confidence in doctors and nurses working at the critical care units; they relied on them to provide best care, make appropriate health care decisions, and get honest answers for their questions whatever the outcomes. Assurance has been identified as family members’ hoping for positive outcomes [7,11].

Unlike [27,28] who found information subscale to be the most important need by family members, in this study the needs for information ranked second. Family members emphasized the importance to know how the patient is being treated medically and the importance of getting information. Family members seek information either by asking health care providers or through their direct involvement in their patients’ care. Getting such information can reduce the level of anxiety and the uncertainty about the patients’ condition and prognosis [7,11].

The needs for proximity ranked third by the family members. This result was consistent with most of the research in the western counties [25,27,28]. However, it was inconsistent with Koski and Warren [26] where proximity ranked second by family members. Given the limited visiting hours in some hospitals where members could be with their patients for a short period of time, family members perceived theses needs as important.

In terms of least important needs, families ranked both comfort and support subscales as lowest. This result was consistent with many studies [16,27,28] and contrasted with others [26]. The least important support needs were ‘to be alone at any time,’ and ‘to have a place to be alone while in the hospital.’ In the Jordanian culture, there are strong social bonds existed between families where everyone supports the other during any stressful event. Moreover, families’ supporting hospitalized patients is considered a social duty by their relatives and friends. This might decrease the family members’ perceptions of the need for support in front of their needs for information and proximity.

In this study, family members of patients at private hospitals perceived the need of assurance more important than family members of the patients hospitalized at public hospitals. The relation between the type of the hospital and family members perceptions of the needs have been not investigated in other studies [3,15]. However, a possible explanation for these findings may be that the family members of patients at private hospitals may need to receive care that reflect their payment where public hospitals cost families less money compared to the private hospitals.

Although hindered by limitations of design and sampling procedure, the current study contributed positively to literature by presenting further data on family needs. The study findings can help nurses give more attention to the psychological needs of the family members and to involve these needs in their plan of care. In addition, these findings can help nurses modify their practices and change focus to more holistic family-centred care in which the needs of the patient as well as the family members are included in their plan of care. Policy makers should also revise the hospitals’ policies of visiting hours to such critical care units, the availability of comfortable furniture at the waiting rooms and other family members’ physical needs.

Conclusion

This study aimed to describe family members’ of critically ill patients’ perceptions of needs. The family members in the current study perceived assurance, information, and proximity higher than comfort and support needs. Families from private hospitals perceived assurance needs higher than families of public hospitals given their expectations. The study has several implications for medical and nursing practice where fulfilling family needs is congruent with the holistic practice widely advised. Furthers studies are recommended using samples from all medical sectors (military and other educational hospitals) and using random sampling technique from wider geographical areas.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge all hospitals and family members who participated in this study.

References

- Davidson J E, Powers K, Hedayat K M, Tieszen M, Kon A A, et al. (2007) Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patientcentered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med 35(2): 605–622.

- Fox Wasylyshyn S, El Masri M, Williamson K (2005) Family Perceptions of Nurses’ Roles toward Family Members of Critically Ill Patients: A Descriptive Study. Heart & Lung 34(5): 335-334.

- Lee L, Lau Y (2003) Immediate Needs of Adult Family Members of Adult Intensive Care Patient in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical Nursing 12(4): 490-500.

- Miracle Vickie (2006) Strategies to Meet the Needs of Families of Critically Ill Patients. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing 25(3): 121- 125.

- Mitchell M, Chaboyer W, Burmeister E, Foster M (2009) Positive Effects of a Nursing Intervention on Family Centered Care in Adult Critical Care. American Journal of Critical Care 18(6): 543-552.

- Al Motlaq M, Carter B, Neill S, Hallstrom I, Mandie Foster et al. (2018) Toward developing consensus on Family Centred Care: An international descriptive study and discussion. Journal of Child health care.

- Morton P, Fontaine D, Hudak C, Gallo B (2018) The Concept of Holism Applied to Critical Care Nursing Practice. In: Morton P & Fontaine D (Eds.), Critical Care Nursing-a holistic approach (11th ed.) Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, Virginia, USA.

- Jane Stover Leske (2002) Interventions to Decrease Family Anxiety. Critical Care Nurse 22(6): 61-65.

- El Masri M, Fox Wasylyshyn S (2007) Nurses’ Roles with Families: Perceptions of ICU Nurses. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 23(1): 43-50.

- Molter N C (1979) Needs of Relatives of Critically Ill patients: a Descriptive Study. Heart & Lung 8(2): 332-339.

- Leske Jane (1991) Internal Psychometric Properties of the Critical Care Family Needs Inventory. Heart & Lung 20(3): 236-243.

- Al Hassan M, Hweidi I (2004) The Perceived Needs of Jordanian Families of Hospitalized, Critically Ill Patients. International Journal of Nursing Practice 10(2): 64-71.

- Bond E, Draeger C, Mandleco B, Donnelly M (2003) Needs of Family Members of Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Implications for Evidence-Based Practice. Critical Care Nurse 23(4): 63-72.

- Fry S, Warren N (2007) Perceived Needs of Critical care Family Members. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly 30(2): 181-188.

- Mendonca D, Warren N (1998) Perceived and Unmet Needs of Critical Care Family Members. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly 21(1): 58-67.

- Omari F (2009) Perceived and Unmet Needs of Adult Jordanian Family Members of Patients in ICUs. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 41(1): 28- 34.

- Omari F, Abu Al Rub R, Ayasreh I (2013) Perceptions of patients and nurses towards nurse caring behaviors in coronary care units in Jordan. J Clin Nurs 22(21-22): 3183-3191.

- Hweidi I, Al-Shannag M (2014) The Needs of Families in Critical Care Settings are Existing Findings Replicated in a Muslim Population: A Survey of Nurses’ Perception. European Journal of Scientific Research 116: 518-528.

- Al Ghabeesh S H, Abu Snieneh H, Abu Shahror L, Abu Sneineh F, Alhawamdeh M (2014) Exploring the Self-Perceived Needs for Family Members Having Adult Critically Ill Loved Person: Descriptive Study. Health 6.

- Molter N, Leske J (1983) Critical Care Family Needs Inventory.

- Ministry of health (2019) Health Sector Bodies.

- Latour J, Hazelzet J, Duivenvoorden H, Goudoever V (2010) Perceptions of Parents, Nurses, Physicians on Neonatal Intensive Care Practices. Journal of Pediatrics 157(2): 215-220.

- Mundy Cynthia (2010) Assessment of Family Needs in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. American Journal of Critical Care 19(2): 156-163.

- Browning G, Warren N (2006) Unmet Needs of Family Members in the Medical Intensive Care Waiting Room. Critical Care Nurse Quarterly 29(1): 86-95.

- Maxwell K, Stuenkel D, Saylor C (2007) Needs of Family Members of Critically Ill Patients: A Comparison of Nurse and Family Perceptions. Heart & Lung 36(5): 367-376.

- Kosco M, Warren N (2000) Critical Care Nurses’ Perceptions of Family Needs as Met. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly 23(2): 60-72.

- Kinrade, Trish (2009) The Psychosocial Needs of Families during Critical illness: Comparison of Nurses’ and Family Members’ Perspectives. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 27(1): 82-88.

- Bijttebier P, Vanoost S, Ferdinande P, Frans E (2001) Needs of Relatives of Critical care Patients: Perceptions of Relatives, Physician and Nurses. Critical Care medicine 27(1): 160-165.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.