Case Report

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Lingual Nerve Microsurgical Repair: A Case Report and Literature Review

*Corresponding author: Ullyanov Bezerra Toscano de Mendona, Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro- UFRJ, RJ, Brazil.

Received: July 29, 2020; Published: August 21, 2020

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2020.10.001466

Introduction

Injury to the lingual nerve (LN), a peripheral branch of the trigeminal nerve, can result from a wide variety of oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures. The lingual nerve, along with the inferior alveolar nerve, is one of the most commonly injured nerves during oral surgery. Numerous procedures are thought to cause lingual nerve damage, including third molar extraction, tumour excision, salivary gland excision, dental implant placement, laryngoscopy and general dental manipulation, such as local anaesthesia injection [1].

The lingual nerve supplies sensation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, the floor of the oral cavity, oral gingivae and sublingual gland, carries nerve fibers from the chorda tympani nerve, a branch of the facial nerve, which supplies taste and autonomics to the same area [2].

Even though the spontaneous nerve recovery rates within 6 months of damage are high [3], a small number of cases present with permanent sensory disfunction. [4,5] If such injuries are incurred and symptoms do not resolve, the patient should be offered proper and timely assessment for potential microsurgical nerve repair [2].

Currently, there is no conventional treatment or management protocol for these patients. When direct suturing repair is not possible, other options, including an autologous nerve graft (sural/greater auricular nerve), processed nerve allograft and tube conduits to bridge the gap between stumps, should be considered [2].

Case Report

A 26-year-old Caucasian female with no medical history was referred to our department for evaluation and treatment of chronic neuropathic pain in her tongue. The pain was developed after the extraction of the right mandibular third molar. It had been approximately 15 months since the injury when the patient was first examined at the clinic. According to the patient, she experienced loss of sensation immediately after surgery and pain starting 1 month after extraction, continuous tingling and numbness, changes in swallowing, touch and taste perception along the right side of her tongue, as well as severe superimposed “electric” pain shocks.

Neurological examination revealed anaesthesia confined to the right anterolateral part of the tongue. Taste discrimination was absent in the same area. Objective neurosensory function assessment, there was no reaction to a pinprick test with needle. Thermal discrimination was absent, although brush stroke sensation was recognized. Further oral cavity examination was normal, except for pain elicited by palpation of right retromolar area (Tinel sign). Tongue motion was unimpaired and other neurological signs and symptoms were absent.

Before our evaluation, patient received injections of local anaesthetic medication and steroids for trigeminal nerve block three times and comprehensive medical treatment with psychiatry assessment, acupuncture sessions, low intensity laser therapy, as well as pregabalin and venlafaxine prescription, with no effectiveness. After multiple follow-up visits, the patient had experienced no symptoms relief. No definitive treatment was ever offered by other healthcare providers.

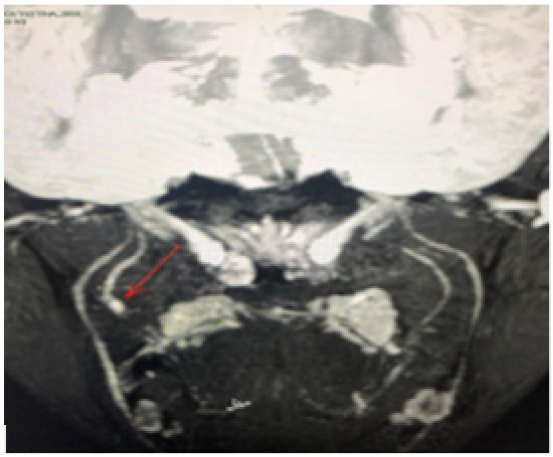

Patient underwent a magnetic resonance neurography of the lingual nerve, which showed a neuroma on the right LN and a section area (Figure 1). Based on the patient’s medical history, a potential microsurgical repair of the LN was offered, with aiming successful restoration of neurosensory function.

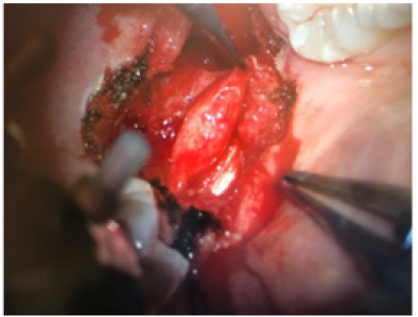

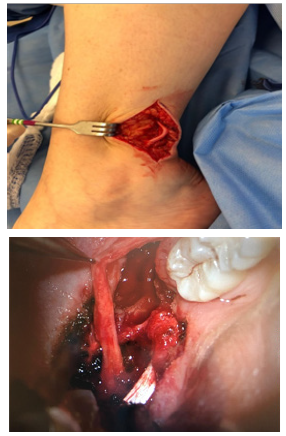

Microsurgical treatment of LN injury was performed with a Head and Neck and Plastic Surgery team, under general anaesthesia. The nerve was exposed after intraoral mucosal incision and a lingual flap reflection. The neuroma was located adjacent to the area of the previously-removed third molar (Figure 2), with an approximately 30mm defect between the distal and the proximal stump of the torn LN. Next, the following procedures were performed with appropriate magnification, using an operating microscope: external decompression, internal neurolysis, excision of the neuroma and intervening scar tissue, dissection for mobilization of the proximal and distal nerve stumps, reconstruction of the nerve gap with autogenous nerve graft (donor sural) (Figure 3 & 4). Two weeks after the exploration and repair of her right LN, the patient showed a satisfactory recovery, with considerable improvement of disabling pain.

Discussion

Nerves can be severed, stretched or crushed during surgery or trauma. [6,7] The anatomic path of the LN places it at increased risk during procedures on adjacent structures in the oral and maxillofacial region. It is a relatively rare complication that can result in sensory changes, such as numbness, paraesthesia, neuropathic pain, altered taste, distorted speech and diminished pleasures, which leads to a reduction on patient's quality of life [2].

According to most authors, the main cause of LN injury is mandibular third molar extraction. The optimal timing for lingual nerve repair surgery remains controversial. Bagheri et al. observed a 5,8% decrease in the odds of improvement for each month of delay in surgical repair; moreover, injuries with “late” repair (more than 9 months since injury) had a significantly higher risk of non-improvement. Younger patients seem to have better functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury, with a 5,5% decrease in the chance of recovery per year for patients aged older than 45 years [5].

Once exploration and microsurgical nerve repair is recommended, there are many reconstructive techniques that may be applied, such as external decompression or tensionless primary repair with direct neurorrhaphy.

Pogrel [8] found that early repair appeared to have better outcomes than late repair [8]. On the other hand, Robinson et al. [9] studied neuroma excision and nerve stump anastomosis, resulting in significant improvements in the sensory, gustatory and functional outcomes for most patients, regardless of the time of repair. For Robinson et al. [9] the results of primary repair seem to be better than the ones reported with other surgical methods [9].

Rutner et al. [10] showed 85% of neurosensory improvement and a 90% rate of reported subjective improvement, among which 50% were described as moderate or significant [10].

Conclusion

In this case report, reconstruction of injured LN, with autogenous sural nerve graft bridging proximal and distal nerve ends after neuroma excision, was an efficient surgical therapy for neurosensory improvement and pain relief, even though it was performed 18 months after nerve damage. No spontaneous recovery was observed prior to surgery and no surgical complications occurred during the follow-up period.

References

- Fagan SE, Roy W (2020) Anatomy, Head and Neck, Lingual Nerve. [Updated 2019 Aug 19]. In: StatPearls Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Ducic I, Yoon J (2019) Reconstructive Options for Inferior Alveolar and Lingual Nerve Injuries After Dental and Oral Surgery: An Evidence-Based Review. Ann Plast Surg 82(6): 653-660.

- Chossegros C, Guyot L, Cheynet F, Belloni D, Blanc JL (2002) Is lingual nerve protection necessary for lower third molar germectomy? A prospective study of 300 procedures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 31(6): 620-624.

- Shintani Y, Ueda M, Tojyo I (2020) Change in allodynia of patients with post-lingual nerve repair iatrogenic lingual nerve disorder. Oral Maxillofac Surg 24(1): 25-29.

- Bagheri SC, Meyer RA, Khan HA, Kuhmichel A, Steed MB (2010) Retrospective review of microsurgical repair of 222 lingual nerve injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 68(4): 715-723.

- Rees RT (1992) Permanent damage to inferior alveolar and lingual nerves Br Dent J 173:123-124.

- Cheung LK, Leung YY, Chow LK, Wong MC, Chan EK, et al. (2010) Incidence of neurosensory deficits and recovery after lower third molar surgery: a prospective clinical study of 4338 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 39: 320-326.

- Pogrel MA (2002) The results of microneurosurgery of the inferior alveolar and lingual nerve. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 60(5): 485-489.

- Robinson PP, Loescher AR, Smith KG (2000) A prospective, quantitative study on the clinical outcome of lingual nerve repair. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 38(4): 255-263.

- Rutner TW, Ziccardi VB, Janal MV (2005) Long-Term Outcome Assessment for Lingual Nerve Microsurgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surgery 63(8): 1145-1149.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.