Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

The Effect of User Charges on the Pattern of Health Care Demand in Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Lloyd Ahamefule Amaghionyeodiwe, Department of Business and Economics, York College, City University of New York (CUNY), USA

Received: August 24, 2020; Published: September 09, 2020

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2020.10.001494

Abstract

The economic downturn in early 1980s in Nigeria led to the introduction and implementation of user charges in government health care facilities. This coupled with the persistent poverty level in Nigeria raises the question of consumers’ ability and willingness to pay these user charges. Accordingly, using primary data, this study examined the possible trade-off between user charges and demand for government health services in Nigeria. The analysis showed that increasing user fees substantially reduced the use of government health facility by low-income earners. Thus, it was recommended, among others, that government should introduce price discrimination into user fees, to be set at marginal cost. This would help avoid the adverse distribution effects of user-fees, especially, on the lower income group.

Keywords: User Charges; Demand for government health services; Willingness to pay and Health care

JEL Classification: I10, I18

Introduction

Healthcare in Nigeria is paid for on a cash and carry basis making out-of-pocket expenses to dominate in households’ payment for health care services. Various studies have shown that majority of the households currently paying through out-of-pocket for health care services in Nigeria. This was in contrast to what obtained prior to the 1980s, when health care services, especially those provide by the public sector, were virtually provided free of charge in Nigeria. During this period, demand for public sector health care services soared and this impacted on government finances and subsequently on the health care infrastructures as well as on the quality of care services provided. This stiffened budgets of the Nigerian government and forced it to undertake major economic reforms, which, among others, have affected their health sectors. One of such reforms in the health sector was the introduction of user charges which entails that household will have to pay for the health care service through out-of-pocket. This was also in line with the Bamako Initiative (BI) announced at a meeting of African Ministers of Health co-sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF in 1987 with the main aim of providing universal access to primary health care (PHC). This is to enable consumers’ and/or households pay some share of the cost of providing these health care services. The aim is to enhance revenue generation from this sector. The revenue thus generated can consequently be re-invested into this sector. But whether enough revenue is generated or not, depends, among others, on the price elasticity of demand for public health services and the consumers’ income level.

With the introduction of user charges, there was an increase in the cost of care being incurred by the households’ and consequently, huge out-of-pocket payments and these payments have had varying effects on the demand for health care services in Nigeria. And given that health care services are provided by the government and private (including religious organization) sectors in Nigeria who charge different prices for their services and with an increase in user fees, there tend to be a possible trade-off on the pattern of usage and choice of provider by the consumers, which is part of the objective of this study.

This notwithstanding, Nigeria is a country with huge human and natural resources and yet the majority of its populace live in poverty. For instance, National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reported that Nigeria’s relative poverty measurement stood at 54.4% in 2004, but increased to 69% in 2010. While absolute poverty, defined in terms of the minimal requirements necessary to afford minimal standards of food, clothing, healthcare and shelter, showed that 54.7% of Nigerians were living in poverty in 2004 but this increased to 60.9% in 2010. Using the-dollar-per-day measure, which refers to the proportion of those living on less than US$1 per day poverty line, 51.6% of Nigerians were living below US$1 per day in 2004, but this increased to 61.2% in 2010, although the World Bank standard is now US$1.25. National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) further reported that subjective poverty, which is based on self-assessment and “sentiments” from respondents indicated that 75.5% of Nigerians considered themselves to be poor in 2004, and in 2010 the number went up to 93.9%. This extreme poverty limits the ability to pay for this health service and thus having access to quality health care. This could affect the pattern of health care demand in Nigeria.

From the above, one pertinent question is the ability and willingness’s of these households’ to pay these user charges, especially when there are no health care insurance in Nigeria (though this have been initiated but not implemented). The ability and willingness to pay (which may not directly covary), therefore, determines the quantum and quality of the medical care obtainable by the populace. Households may both have the willingness to pay, but the ability to pay will be lacking, especially, in the poor. It is as a result of this that this study investigates the effect of user charges payments on the pattern of health care demand in Nigeria.

Methodology and Data Source

Method of Analysis

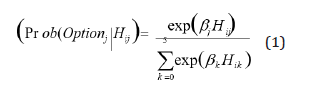

This study utilized both a Multinomial Logit Model (MNL) and Simulation techniques in investigating whether or not the imposition user charges in public sector health care facilities can lead to large reductions in the usage of the services of the sector or can cause shifts across types of care used. In this study a multinomial logit (MNL) model is used because we assumed that the alternative options provide distinct choices, have different attributes and can be considered to be mutually exclusive. And also, the patient’s alternative choices are more than two. This is in line with nearly all studies that concentrate on the provider’s choice, [1-6]. More specifically, assuming that each eij for all alternatives j is distributed independently and identically in accordance with the extreme value distribution, the demand for provider j (that is, the probability that a patient will choose alternative j) is given by [equation 1]. The demand function for a provider is thus the probability that the utility from that alternative is higher than the utility from any of the other alternatives.

The parameter of this model can be estimated using maximum-likelihood methods. In our data the unit of observation is the individual. The estimated demand functions were then used to project (using simulation techniques) the effect of user fees on demand for health care.

Data Type and Source

The study utilized mainly primary data which was individual and household based. Both stratified random and cluster-sampling techniques was also used in selecting the study’s sample population. This was supplemented with a health facility survey. Facilities were selected for interviewing on the basis of proximity to a household cluster (this is a geographic area such as a village or neighborhoods of a city).

The survey collected health and socioeconomic information such as household consumption, demographic characteristics, time use, income and consumption, education and health status. The household sample included both individuals who do not report as well as those who reported an illness within four weeks of the survey. Providers’ quality1 was measured by the availability of essential drug; the number of medical staff as an indicator of the level of human resources available at the facility which may reflect the sophistication and range of health services provided; the provision of basic adult and child health services measured by the availability of a functioning laboratory, the ability to vaccinate children and the ability to provide prenatal, postnatal and child growth monitoring services (grouped together as ‘mother and baby care’); the availability of essential infrastructures like electricity and running water. Income was measured as total household income in the month prior to the survey while the per capita monthly income was calculated using data for members of the household. The prices for each provider where not directly available was constructed from the money price and/or cost information for each provider given by care recipients. For those who utilized care, these money prices and/or cost data were available, but unavailable for those who did not utilize health care. Thus, for each provider, the available (money) cost information was used to estimate cost/price. The non-monetary access utilization price was measured by travel and service time of the providers.

Data Analysis and Findings

Nested Multinomial Logit (NMNL) Results

Table 1: Multinomial Logit Estimates of Choice of Health Care Provider.

‘t’-statistics are in brackets ‘a’- the co-efficients are restarted to be equal across equations ‘b’- Price of consultation covers the fee for the service in Nigeria (***), (**) Significant at 1% level and 5% level respectively.

The Nested Multinomial Logit (NMNL) model was estimated using full maximum likelihood estimation method. The NMNL nested the choice of provider within the choice of whether to seek care at all. The results are presented in Table 1.

As was expected, the price of the consultation was negatively related to the demand for modern health care and thus tend to discourage demand. By implication, as the price increases the probability of seeking modern health care tend to reduce. Also, any increase in the price of consultation (a form of user fees being charged) do have two major effects, namely a reduction in the probability of that facility being chosen and secondly, a reduction in the probability of choosing a modern or professional care. Distance (travel time) was also negatively related to the demand for both private and public health care facilities. This effect of distance was estimated with the co-efficient been restricted to be equal across equations. The reason for this is to help reduce or minimize the disparity in the opportunity cost of time that will be incurred in traveling to the health facility. This has been argued to be a more important cost incurred in traveling to the health facility [7] and it is equal to the time lost during travel (proportional to distance) multiplied by the hourly wage of the individual (which, on average, is proportional to income). On reason for this is the opportunity cost of time that will be incurred in traveling to the health facility. If the opportunity cost is large, it discourages households from seeking professional care, but if it is relatively less or small, it encourages the demand for professional care by households. For the government employee variable, price is positively related to the demand for the public sector facility but negatively related to the demand for private facility. It was significant at 1% for public sector health facilities while for private sector facilities it was not significant. This result could be a manifestation of the policy, which entails government employees, and their families to have access to health care services at public sector health facilities free of charge or at a subsidized price. This implies that with such a government policy, the probability of government employees and their relatives choosing a public sector health facility becomes higher relative to that of a private facility. With this result, the government employee dummy can be interpreted as a price effect and not as a quality effect. This result was similar to that of [7].

Likewise, any increase in non-monetary access cost may reduce the demand for professional care. With respect to the quality variables, they (drug availability, infrastructure, Personnel and Services) were all positively related to the demand for professional care implying that households prefer health facilities with adequate and qualified health personnel, up-to-date (modern and well functioning) infrastructure, quality, adequate and diverse health services [8-10]. The consequence of this is that households will opt for health facilities where drug and diverse services are available, infrastructure are functioning well and there are qualified personnel (doctors and nurses), which they, the households, will prefer to treat them. The implication of this is that households take into account the various dimension of quality of care in making their choices of which health facility to use. Also, the result indicates that households attach more importance to the probability of their being treated by qualified personnel (doctor or nurse). All these may also attract higher user charges (prices).

Simulation Results

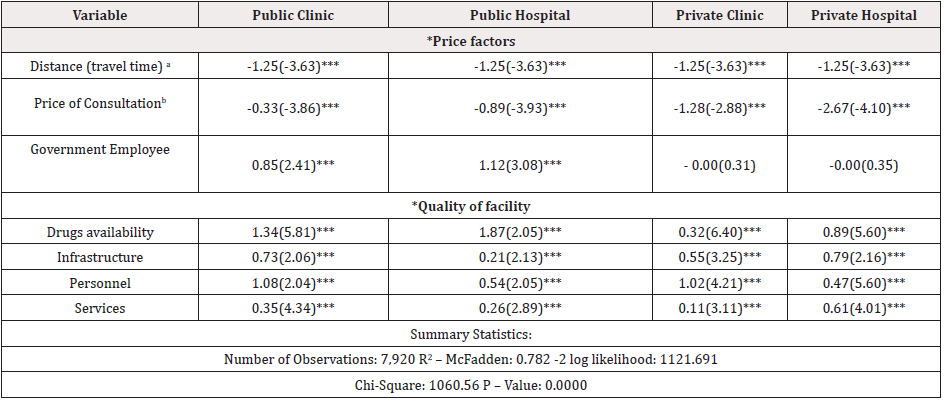

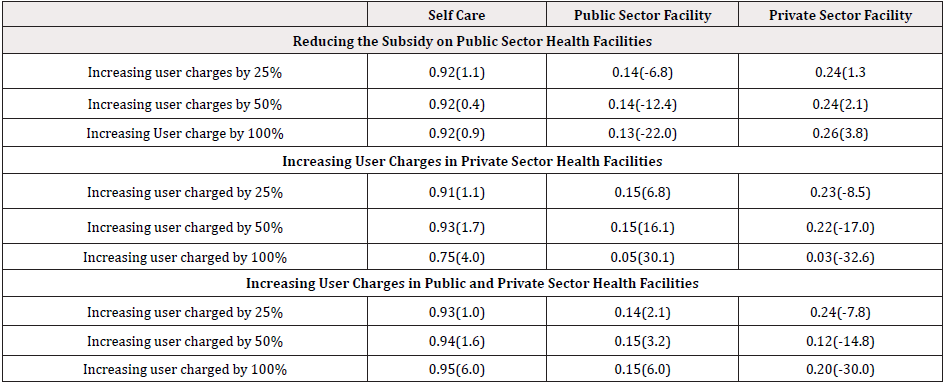

Using the multinomial logit model and applying the comparative static analysis method, the impact of changes in user fee or charge for the public sector and or private sector facilities on health care demand and the choice between private sector and public sector care based on the average characteristics of the individuals and facilities in the sample was simulated [11-14]. To do this, we calculated the probability of each choice and the percentage change relative to a referenced baseline, which was the choice at the mean of the sample characterizes. Different scenarios were examined and this includes: increasing user charges in public sector health facilities; increasing user charges in private health facilities; increasing user charges for both private and public sector facilities and when individuals were allowed to substitute private sector care and self-care for public sector care, which became relatively more expensive. The result of this is contained in Table 2.

Table 2: Simulation Result from Different Scenario Analysis using Probabilities and Percent Change in Health Care Use.

Note: percentage changes are in brackets. These are percentage changes relative to a referenced baseline, which was the choice at the mean of the sample characteristics.

In line with a prior expectation, increasing user charges in public sector health facilities led to a decrease in the usage of public sector health facilities while it tend to increase the use of private sector health facilities and that of self-care. The higher the increase in the user charges the more it will affect the usage of the various categories of care. For instance, when user charges were increased by 50%, it led to a fall of 12.4% in the use of public sector health facilities while that of the private sector health facilities and self care increased by 2.1% and 0.4% respectively [15-18]. A 100% increase in user charges in public sector health facilities increases private sector health care facility usage by 3.8%, while it increased the usage of the self care option by 0.9%. By inference, increasing user charges in public sector health facilities tend to discourage the use of these facilities and encourage the use of self-care and private sector facilities. Also, when the user charges in the private sector health facilities were increased, it also had a negative effect on its usage [19]. For instance, when the user charges for the private sector health facilities was increased by 25%, usage of these facilities were reduced by 8.5% while those of the public sector and self care increased by 6.8% and 1.1% respectively. Also, when the user charges were increased by 50%, the usage rate for public sector facilities rose by 16.1%, self-care rose by 1.7%, while private sector facilities usage fell by 17.0%. The usage of private sector health facilities further fell by 32.6% when the user charges in these facilities were increased by 100%. In this scenario, the usage rate of public sector facilities rose by 30.1%, while those of self-care rose by 4.0%. One implication from the simulation is that the results indicate that the cost of care have an influence on the utilization rate of professional health care services. This is because increasing the user charges for private facilities led to a reduction in the usage of the facility and encouraged the usage for alternative care (self-care and public sector facility) [21-24]. Also, when the user charges for both private and public sector facilities are increased, the effect was felt more by the private facilities. And when all modern health care opportunities become more expensive, households tend to resort more to using public sector health care. Increasing user fees by 25% in both facilities led to a decrease in the usage rate of private facilities by 7.8%, while that of public sector facilities and self-care rose respectively by 2.1% and 1.0%. A 50% increase in the user fees charged, also led to a reduction in utilization rate of private sector health facilities by 14.8% while those of the public sector and the self-care option increased by a respective 3.2% and 1.6%. When the user fee was finally increased by 100%, the demand for private sector health facility fell by 30.0%, that of self-care also increased by 6.0%. The result demonstrated a significant negative relationship between changes in the cost of treatment and the use of private sector and public sector health facilities, thereby indicating that there tend to be a significant positive relationship between changes in the cost of treatment and the usage of the self-care option.

Conclusion

From the analysis, it is apparent user charges substantially reduce the utilization level of the public sector health facility by the poor, as such government can and should introduce price discrimination into the user fee it charges. This will help avoid the adverse distribution effects which user fees have. User fee at clinics in poorer villages and communities can be set at different levels than user fee in rich communities and as long as the user fee is below the welfare neutral prices the policy will be welfare improving for everyone [25]. More so, the degree to which the price is below the welfare neutral price determines the improvement in the welfare and utilization of medical care achieved by the policy [26-30]. With this type of price discrimination the clinics in richer villages or areas will be self-financing, while the facilities in poorer villages require a subsidy. Furthermore, Drugs, infrastructure, qualified personnel, efficient and diverse services should likewise be provided in public sector health care facilities as it will lead to increased usage of public sector health facilities even at a higher cost. This notwithstanding, since the price of consultation is negatively related to health care utilization, it becomes evident that any increase in these fees will reduce the chance of that facility being chosen as well as reducing the chance of choosing modern health care. Thus, government pricing of these services should also bias towards the poor.

References

- Mwabu G, Ainsworth M, Nyamete A (1993) Quality of Medical Care and Choice of Medical Treatment in Kenya: An Empirical Analysis. Africa Technical Department, working paper No.9, April, The World Bank.

- Tembon Andy C (1996) Health care provider choice: The North West Province of Cameroon. International Journal of Health Planning and Management 11: 53-57.

- Jianghui Li, Cao Suhua, Henry Lucas (1997) Utilization of health services in poor rural China: An analysis using a logistic regression model. IDS Bulletin 28(1).

- Dor A, Gertler P, J Van der Gaag (1987) Non-price Rationing and the Choice of Medical Care Providers in Rural Cote d'Ivoire. J Health Econ 6(4): 291-304.

- Dor, Avi van der Gaag, Jacques (1987) The Demand for Medical Care in Developing Countries: Quantity Rationing in Rural Cote d’Ivoire. Living Standards Measurements Study Working Paper No.35, World Bank, Washington DC, USA.

- Bedi, Arjun S, Paul Kimalu, Mwangi Kimenyi, Damiano Manda, et al. (2003) User Charges and Utilization of Health Services in Kenya. Working Paper Series No. 381 Institute of Social Studies, The Hague-The Netherlands.

- Lavy Victor, Jean-Marc Germain (1994) Quality and Cost in Health Care Choice in Developing Countries. Living Standards Measurement Study Paper No. 105. World Bank, Washington DC, USA.

- Adeoti AI, Awoniyi OA (2012) Determinants of Child and Maternal Health Status and Demand for Health Care Services in Nigeria. Africa Portal Library A Project of the African Initiative.

- Adeoti AI, Awoniyi OA (2014) Demand for Health Care Services and Child Health Status in Nigeria- A Control Function Approach. African Reseach Review: An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia 8(1) Serial No. 32.

- Akin JS, Hutchinson P (1999) Health-Care Facility Choice and the Phenomenon of Bypassing. Health Policy and Planning 14(2): 135-151.

- Akin J, Gulkey D, Hazel E (1993) Multinomial Profit Estimation of Health Care demand: Ogun state, Nigeria", Department of Economics, University of North Carolina, hapel Hill, N.C.

- Akin JS, Gulkey DK, Hazel E (1995) Quality of service and demand for health care services in Nigeria: A multinomial probit estimation. Soc Sci Med 40(11): 1527-1537.

- Alderman H, Gertler P (1989) The substitutability of public and private health care for the treatment of children in Pakistan. LSMS working paper, 57, Washington D.C. World Bank.

- Amaghionyeodiwe A Lloyd (2008) Determinants of the Choice of Health Care Provider in Nigeria. Health Care Manag Sci 11(3): 215-227.

- Arendt Jacob Nielsen (2012) The Demand for Health Care by the Poor under Universal Health Care Coverage. Journal of Human Capital 6(4): 316-335.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2008) Nigerian Health System 2008. Federal Ministry of Health Federal Republic of Nigeria.

- Garner P, Thomason J, Donaldson D (1990) Quality Assessment of Health Facilities in Rural Papua New Guinea. Oxford University Press.

- Gething Peter W, Amoako Johnson, Faustina F, Nyarko P, Angela B, et al. (2012) Geographical access to care at birth in Ghana: a barrier to safe motherhood. Center of Population Change Working Paper, 21. Southampton, GB, 34pp.

- Gross Tal, Jeremy Tobacman (2014) Dangerous Liquidity and the Demand for Health Care: Evidence from the 2008 Stimulus Payments. Journal of Human Resources 49(2): 424-445.

- Hyman Mark (2014) Why Obama Care is Not Enough: Turning off the Demand for Health Care. October.

- Ichoku HE, Fonta WM (2006) The Distributional Impact of Healthcare Financing in Nigeria: A Case Study of Enugu State. PMMA Working Paper 2006-17.

- Jianghui Li, Cao Suhua, Henry Lucas (1997) Utilization of health services in poor rural China: An analysis using a logistic regression model. IDS Bulletin 28(1).

- Santosh Kumar, Dansereau Emily, Murray Christopher (2012) Does Distance Matter for Institutional Delivery in Rural India: An Instrumental Variable Approach. (October 1).

- National Bureau of Statistics (2012) Annual Abstract of Statistics. Abuja.

- National Bureau of Statistics (2012) The Nigeria Poverty Profile 2010 Report. Abuja.

- Mwabu G, Martha Ainsworth, Andrew Nyamete, (1996) The effect of prices, service quality and availability on the demand on the demand for medical care: Insights from Kenya. In R. Paul Shaw and Martha Ainsworth (eds.), Financing health services through user fees and insurance: Case studies from Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Discussion Papers 294, Africa Technical Department Series. Washington DC, USA.

- Olaniyan O, Sunkanmi OA (2012) Demand for Child Healthcare in Nigeria. Global Journal of Health Science 4(6): 129-140.

- Peabody JW, Rahman O, Fox K, Gertler P (1993) Measuring Quality in Primary Health Care Facilities in Jamaica. RAND.

- Sarma S (2009) Demand for outpatient Healthcare: empirical findings from rural India. Appl Health Econo Health Policy 7(4): 265-277.

- World Health Organization (2006) Medicine Prices in Nigeria:Prices People Pay for Medicines. World Health Organization. Geneva.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.