Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Association Between Obesity and Sleep Problems in Adolescents

*Corresponding author: Li Li, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA.

Received: January 26, 2021; Published: January 29, 2021

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2021.11.001673

Abstract

Background: The purpose of this study is to determine if adolescents with overweight or obesity are more susceptible to Sleep-related Breathing Disorder (SRBD), and if chronic inflammation is a potential pathway linking them.

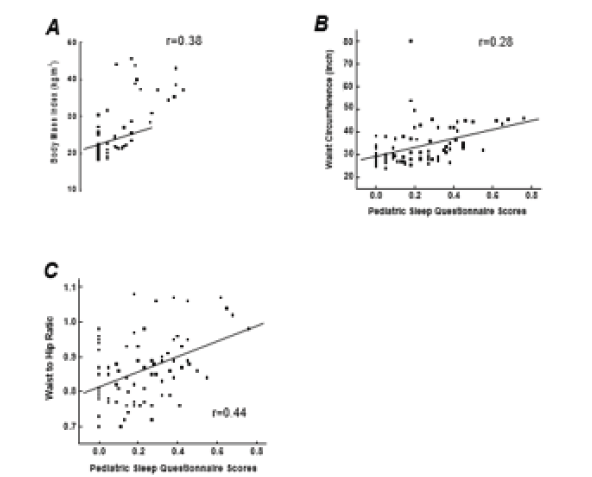

Methods: Body mass index (BMI), and waist and hip circumferences were measured in 90 adolescents aged 15-18. Participants were stratified into overweight/obesity group (BMI percentile≥85%) and control group (BMI percentile <85%) per the CDC growth chart. Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ) was used to assess SRBD symptoms, including snoring, daytime sleepiness and hyperactive behavior (Figure 1). Participant‘s early life stress was assessed using the Childhood Trust Events Survey. Blood samples were collected for measuring the inflammatory factors.

Figure 1: Correlations between pediatric sleep questionnaires and adiposity measures including body mass index in A, waist circumference in B, and waist to hip ratio in C (correlation coefficients were 0.38, 0.28, and 0.44, respectively, all p<0.05).

Results: Partial correlation analysis indicated that BMI percentile, waist circumference, and waist to hip ratio were positively correlated with PSQ scores in adolescents (r=0.29, p=0.012; r=0.28, p=0.013; r=0.44, p<0.001, respectively) after controlling for depression, gender, race, early life stress, smoking, family income, and parental education. Levels of interleukin (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) significantly correlated with PSQ scores (r=0.33, p=0.01; r=0.27, p=0.046, respectively). In addition, IL-6 significantly correlated with snoring (r=0.26, p=0.04). TNF-α and IL-8 were correlated with hyperactive behavior (r=0.32, p=0.01; r=0.26, p=0.04, respectively). The PSQ score could be predicted by IL-6, TNF-α, C-reactive protein, and adiponectin in the overweight/obese group.

Conclusion: Our results suggest that being overweight or obese is more susceptible to SRBD measured by the PSQ through elevated inflammatory factors in adolescents. The association between SRBD, obesity, and chronic inflammation warrant further investigation due to potentially being a target for intervention.

Keywords: Body Mass Index; Waist to Hip Ratio; Obesity; Sleep Problems; Adolescents

Abbreviations: SRBD: Sleep-related Breathing Disorder; BMI: Body Mass Index; ELS: Early Life Stress; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-α; IL: Interleukin; CDC: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; PSQ: Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire; WHR: Waist to Hip Ratio

Introduction

Childhood obesity has emerged as one of the most serious public health concerns over the past 30 years. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey shows the prevalence of obesity, defined as having a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile for age and sex, in 2-19 year old youth was 16.8% in 2007–2008 and increased to 18.5% in 2015-2016 [1-3]. During childhood, the development of obesity can cause several adverse health effects such as poor mental health, increased risk of developing medical conditions such as heart disease and worsened neurocognitive functioning [4]. Because childhood obesity is a strong risk factor for adult obesity, risks for certain types of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, osteoarthritis, and type 2 diabetes and other comorbidities are also increased throughout the lifespan [4-5]. Studies have indicated that inappropriate sleep quantity, schedules, and quality potentially contribute to obesity because these factors can cause changes in metabolic processes and obesogenic behavior [6]. Sleep problems, including Sleep-related Breathing Disorders (SRBDs), can impair one’s ability to acquire normal sleep and can have harmful effects on the body. Indeed, SRBD, characterized by snoring, hyperactivity, and daytime sleepiness, has become increasingly diagnosed in adolescents and has been associated with obesity although the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood [7,8]. It is important to evaluate sleep problems such as SRBDs in adolescence so it can be addressed earlier in development to have better health outcomes later in life [9]. Since SRBDs and childhood obesity have been noted to be increasingly prevalent pediatric problems, more research is warranted to understand whether adolescents with overweight or obesity are more susceptible to SRBD and to understand how they are associated.

Chronic inflammation plays a role in the development of sleep problems such as SRBDs [10]. Our previous studies and other studies suggest the involvement of inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 in the development of obesity, which is characterized as a low-grade inflammatory status [11-14]. In prior studies, inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and C-reactive protein are also reported to be elevated in individuals with SRBDs in adults [15-17]. Compared to well-rested individuals, leptin levels are decreased in adults with sleep-restriction [18-19]. In contrast, much less is known about leptin and other inflammatory markers in children than in adults. In addition, recent studies have shown conflicting results about leptin levels. While one study found that short sleep duration was associated with lower leptin levels, another study revealed that short sleep duration was associated with higher leptin levels [20-22]. Therefore, further research is needed to clarify the role of inflammatory factors, including leptin, in the relationship between childhood obesity and sleep problems. A cross-sectional study was designed to explore the relationships between sleep problem and obesity in adolescents with a particular focus on SRBD, BMI percentile and waist to hip ratio. The secondary aim of this study was to investigate whether inflammatory factors would be a potential pathway to link sleep problems with obesity in adolescents.

Methods

Participants Recruitment

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) approved this study. Written informed consent was obtained from both the legal guardians and adolescents before any procedures were done. All procedures followed were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Participants were recruited from July 2017 to October 2019 from surrounding Birmingham, Alabama, communities via flyers and media advertisements. Data on age, race, gender, years of education, current cigarette smoking were collected in adolescents by self-report. Highest level of education and family income of the legal guardians were also collected by self-report. Prescription and over-the-counter medications were determined by transcription of medications brought into the laboratory at UAB. A sample of 103 adolescents 15-18 years participated in the study, and 90 completed all study procedures for data analysis. Participants were excluded if they had a psychiatric diagnosis other than depression based on DSM-5 criteria (e.g., psychosis, bipolar disorder, alcohol or substance use disorders), a diagnosed sleep disorder by parent reports or medical records, a prior tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy, a diagnosed immune system disorder, or participation in weight management program. Participants were also excluded if they were taking antibiotics, anti-inflammatory medications in the last 30 days, or medications that affect body weight in the last 3 months. Female participants were excluded if they were pregnant or lactating. Adolescents with depression were included in the study and early life stress (ELS) is thought to be related with depression [23]. Thus, Childhood Trust Events Survey was applied to each participant to assess their prior exposures to adverse events, i.e., ELS [24].

Anthropometrics and Groups

Anthropometric measures were taken in duplicate and averaged in each participant, including height, weight, and waist and hip circumferences. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm by using a mounted stadiometer. Weight was determined to the nearest 0.1 kg by using an electronic scale. Ten percent of height, weight and waist circumference measurements were repeated by a second research staff member to assess inter-rater reliability. Waist and hip circumferences were measured to the nearest 0.1 inch with a Gulick tape measure, and waist circumference was measured at the umbilicus at the end of inspiration. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2), and BMI percentile was determined using the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth charts. According to the CDC growth chart, obese is≥95th percentile, and overweight is ≥85th percentile, respectively, in adolescents [25]. Participants were stratified into an overweight/obese group if their BMI was ≥85th percentile. Others were placed in the control group.

Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire

Sleep problems in adolescents was evaluated by the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ), a 22-item scale that evaluates sleep under the domains of snoring, daytime sleepiness, and hyperactive behavior [26]. The PSQ is used to evaluate sleep symptoms that are often present in disorders such as SRBD and other sleep conditions. Polysomnography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of SRBDs and other sleeping disorders [27]. When polysomnography is not available or difficult to utilize, the PSQ is a validated and dependable way to pinpoint SRBDs or related symptoms [26]. The PSQ is also very useful for evaluating sleep in larger samples because it is more easily administered [7]. The PSQ is designed to be completed by their parents or guardians with a sensitivity and specificity of 0.81 and 0.87, respectively for correct classification of polysomnographically-defined sleep disordered breathing [26]. A parent responds “yes=1”, “no=0”, and “don’t know = missing” to each item. A mean score is summed and divided by the number of items rated “yes”. The mean score can vary from 0.0 to 1.0. Participants who have a cut-off score of ≥0.33 are likely having a diagnosis of SRBD.

Blood Samples Collection and Measurement

Fifteen milliliters of blood were drawn from each participant, centrifuged at 3000g for 15 mins, immediately divided into aliquots, and frozen at -80°C until analysis. The analysis for inflammatory factors, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and TNF-α, was performed using a Meso Scale Discovery multiplex spot assay and analyzed with MSD Discovery Workbench software (Gaithersburg, MD). Concentrations for the inflammatory factor were expressed in pg/ml. C- reactive protein (CRP, mg/L) was analyzed using immunoassay on a Stanbio Sirrus Analyzer (Stanbio Laboratory, Boeme, TX). Leptin and adiponectin (expressed in ng/ml and µg/ml, respectively) were assayed using commercially available radioimmunoassay kits according to the procedures supplied by the manufacturer (Millipore Corp, MA). All samples were run in duplicate and the mean of the duplicate samples were reported.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as count or mean ± standard error unless otherwise stated. Two-sided p-values of <0.05 were considered significant. All variables were tested for normality of distribution by means of Kolmogorov-Smirnoff tests. Variables that deviated greatly from a normal distribution were log10 transformed, including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10 and leptin. A chi-square test for categorical variables and an independent T-test for continuous variables were performed to assess the differences in characteristics between the two groups. ANCOVA was used to compare PSQ score between the two BMI percentile groups with adjustment for gender, race, depression, early life stress, family income and smoking status. ANCOVA was also applied to compare inflammatory factor levels between BMI percentile groups, including CRP, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, leptin and adiponectin after controlling for gender, race, depression, early life stress, and smoking status. Partial correlation analyses were used to estimate the levels of associations between the PSQ total scores and BMI percentile, waist circumference, or waist to hip ratio (WHR) with adjustments for all aforementioned covariates. Linear regression was used to supplement correlational evidence to further evaluate factors that predict PSQ scores. These linear regressions were conducted with BMI percentile, WHR, and waist circumference in separate models with covariates. The participants were then analyzed separately by BMI percentile group. A linear regression was conducted in both groups to evaluate predictive quality of inflammatory factors and to any differences between groups. All covariates and inflammatory factors were added in these models. Mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25 (SPSS Inc., IL).

Results

Participants Characteristics

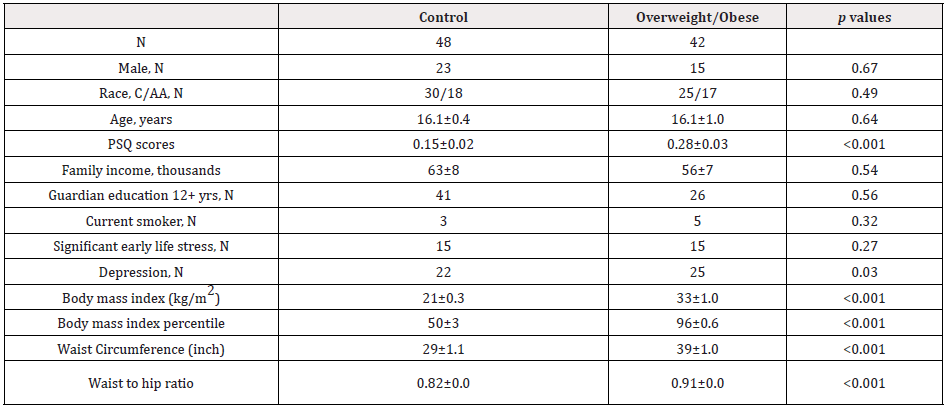

The summary of the characteristics of the 90 participants is presented in Table 1. Participants were separated into the control and overweight/obesity groups based on their BMI percentile. Participants with BMI percentile <85% were placed in the control group, and participants with BMI percentile ≥85% were placed in the overweight/obese group. As shown in Table 1, no significant differences were present in age, gender, race, parents’ education levels, family income, early life stress and smoking status, but there was a significant difference in depression status. Compared to the control group, adolescents in the overweight/obese group had a greater BMI (33±1.0 vs. 21±0.3 kg/m2, p<0.05), BMI percentile (96±0.6 vs. 50±3, p<0.05), waist circumference (39±1.0 vs. 29±1.0, p<0.05), WHR (0.91±0.02 vs. 0.82±0.001, p<0.05), as well as greater PSQ scores (0.28±0.03 vs. 0.15±0.02, p<0.05) after controlling for depression, gender, race, family income, early life stress, and smoking status.

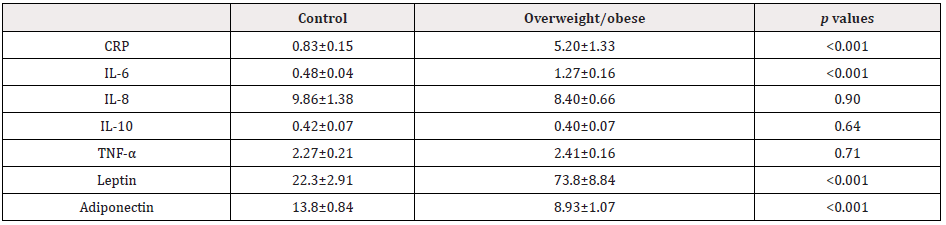

Increased Inflammatory Factors in overweight/Obese Group

To determine if chronic inflammation may be involved in adolescents with overweight or obesity, the levels for several inflammatory factors were measured in adolescents. After controlling for all aforementioned covariates, comparisons between subjects in the two groups revealed that:

- In contrast to the control group, the levels of inflammatory factors, including CRP, leptin, and IL-6, were elevated in the overweight/obese group (Table 2);

- In contrast, adiponectin levels were much lower in the overweight/obese group, and

- No differences regarding IL-8, IL-10 and TNF- α levels were observed between the two groups.

Table 1: Characteristics of Participants

Note: C=Caucasian; AA=African Americans; PSQ=Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire

Table 2: Comparison of Inflammatory Factors

Note: CRP: C-Reactive Protein, IL: Interleukin; TNF- α: T tumor necrosis factor

Relationship Between Psq, Obesity Measures, and Inflammatory Factors

Partial correlation analysis indicated that BMI percentile, waist circumference and WHR were positively correlated with PSQ scores in adolescents (r=0.29, p=0.012; r=0.28, p=0.013; r=0.44, p<0.001, respectively), after controlling for all aforementioned covariates (Fig. 1A-C). Linear regression confirmed having higher BMI percentile, higher waist circumference, and higher WHR significantly predicted PSQ scores (β=0.002, p=0.012; β=0.004, p=0.038; β=0.61, p=0.001 respectively). IL-6 and TNF-α were positively correlated with the PSQ scores (r=0.33, p=0.01; r=0.27, p=0.046, respectively). In addition, IL-6 was positively correlated with snoring (r=0.26, p=0.04). TNF-α and IL-8 were positively correlated with hyperactive behavior (r=0.32 and 0.26, both p<0.05, respectively). When analyzing overweight/obese and control groups separately, the PSQ score could be predicted by IL-6 (β=0.226, p=0.024), TNF-α (β=0.651, p=0.022), CRP (β=-0.312, p=0.007), and adiponectin (β=-0.453, p=0.017) in the overweight/obese group only. Mediation analysis showed that IL-6 had an indirect effect of 30% on the link of WHR with PSQ scores in adolescents.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we found an association of sleep problems, i.e., SRBD, with being overweight or obese, i.e., having higher BMI percentile, and/or greater waist circumference and WHR, in adolescence. In addition, correlations between inflammatory factors and sleep problems were also observed, especially in those who are overweight or obese. IL-6 was found to play a mediational role in the relationship between SRBD measured by PSQ and WHR. These findings were independent of demographics, socioeconomic status, depression, early life stress, and smoking status. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate concomitant associations between obesity, sleep problems and chronic inflammation in 15 to 18 years old adolescents. Several meta-analyses found that decreased sleep duration is a risk factor or marker of developing obesity in infants, children, and adolescents [28,29]. Our own study in adults indicated that poor sleep is associated with abdominal adiposity [16]. Findings from the current study are consistent with our prior findings in adults. These findings also support the previous results from others that there is an association between sleep problems, i.e., SRBD, and overall obesity (measured by BMI percentile, waist circumference and WHR) in adolescents. Moreover, we also considered variables such as tobacco use, socioeconomic status, and mental health status that could be related to both sleep and obesity.

Thus, this study adds important information to the current understanding of the relationship between obesity and sleep problems in adolescence. There is limited literature available on the relationship between inflammatory factors and SRBDs in adolescents, especially focusing on those who are overweight or obese. In a previous study conducted in adults, short sleep duration was associated with higher levels of IL-6 [30]. TNF-α is believed to play a role in sleep regulation and is released in response to sleep loss, in both autocrine and paracrine signaling [31]. In our study, we found that IL-6 predicted sleep problems in adolescents with overweight or obesity. Also, IL-6 predicted snoring which can be a symptom of obstructive sleep apnea. Furthermore, the TNF-α level was associated with both sleep problems, i.e., SRBD, in adolescents with overweight/obesity and hyperactive behavior. Although several other inflammatory factors were elevated in adolescents with overweight or obesity in our study, they were not associated with sleep problems. It seems that individual inflammatory factors may play differential roles based on SRBDs and specific domains of SRBD. Our data analysis did not show an association between sleep problems and inflammatory factors in adolescents in the control group. This may suggest that those with obesity or overweight may have differing inflammatory mechanisms related to sleep compared to those who are not obese or overweight. Future studies are warranted to further investigate the biological mechanisms dictating the relationship between inflammatory factors, obesity, and sleep problems, especially SRBDs, in adolescence. In the present study, our results showed that adolescents with overweight or obesity had elevated leptin levels, however, higher PSQ scores was associated with IL-6 and TNF-α rather than leptin. Our previous study showed that adults with poor sleep and increased visceral fat had elevated leptin levels [16]. However, little is known about the effects of inflammatory factors like leptin and adiponectin in adolescent populations relating to sleep problems and obesity. Recent studies have shown conflicting results when looking at certain sleep factors such as sleep duration, which is another important measure of sleep. While one study showed that short sleep duration was associated with lower leptin levels, another study revealed that short sleep duration was associated with higher leptin levels [20-22]. The lack of consensus in research on the role of inflammatory factors, including leptin, in the relationship between obesity and sleep problems may be linked to study population, study design, different ages of the sample, varied exposure categories, and different confounders adjusted. Specific parameters of sleep problems may also be associated with different inflammatory factors, which may contribute to the conflicting body of evidence. Therefore, more research is needed to conclusively determine which inflammatory factors are truly involved.

The strengths of this study include the adjustments for a wide range of possible confounding factors in data analysis, and simultaneous examination of the associations among sleep problems, inflammatory markers, and obesity. Several limitations should be kept in mind, however, while interpreting our results. The study is a cross-sectional design so it cannot explain the causal relationship between sleep problems and obesity in adolescence. Despite this limitation, our findings stress the importance to control weight for reducing sleep problems, which can be a target for clinical intervention in adolescents. Another limitation of our study is the use of the PSQ to evaluate participant’s sleep problems because it relies on reports from parents on how their child sleeps. This method of reporting could be affected by bias, subjectivity, inattentiveness, and forgetfulness. However, the PSQ has been validated and deemed a reliable research tool by others [26, 32]. In the future, it would be useful to employ an objective method, e.g., polysomnography, to measure sleep rather than parental report to have a more definitive diagnosis. Third, we were unable to analyze if there was a difference between adolescents who were obese compared to overweight, as the sample size required us to group them together. Future studies may consider evaluating these groups individually against a control group. Lastly, adolescents aged 15-18 participated in the current study, but similar studies in the future may need to be performed in other age groups before our study findings could be generalized.

Conclusion

In conclusion, higher PSQ scores in adolescents was found to be associated with higher BMI percentile, higher waist circumference and higher WHR, even after adjusting for confounding factors. In addition, some inflammatory factors, including IL-6, could predict the PSQ scores in adolescents with overweight or obesity, and mediate the association between obesity and PSQ scores. Our findings suggest that periodic assessment of sleep problemsrelated symptoms in at- risk groups such as adolescents with overweight or obesity may help identify those needing sleep- related interventions. Our study also provides a better understanding of a complex relationship among obesity, sleep problems and inflammatory factors.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of Maryellen Williams of the UAB Metabolism Core Laboratory with laboratory analyses.

Author Contribution

MSM wrote the manuscript, collected the data, and performed statistical analysis. AYC collected the data, performed statistical analysis, and edited the manuscript. LL conceptualized and designed the study, supervised the study, edited the manuscript and performed statistical analysis. All authors helped to write the manuscript and approved the final version.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

References

- Hardy JD (1989) Aneurysm of aberrant right subclavian artery and Ondine's curse. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 97(2): 319-320.

- Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM (2000) Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 320 (7244): 1240-1243.

- de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, et al. (2007). Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 85(9): 660-667.

- Yanovski JA (2015) Pediatric obesity. An introduction. Appetite 93:3-12.

- Gungor NK (2014) Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. Journal of clinical research in pediatric endocrinology 6(3): 129-143.

- Jacqueline F Hayes, Katherine N Balantekin , Myra Altman , Denise E Wilfley, C Barr Taylor, et al. (2018) Sleep Patterns and Quality Are Associated with Severity of Obesity and Weight-Related Behaviors in Adolescents with Overweight and Obesity. Child Obes 14(1): 11-17.

- RD Chervin, JE Dillon, C Bassetti, DA Ganoczy, KJ Pituch, et al. (1997) Symptoms of sleep disorders, inattention, and hyperactivity in children. Sleep 20(12): 1185-1192.

- Yue Ma, Liping Peng , Changgui Kou, Shucheng Hua, Haibo Yuan (2017) Associations of Overweight, Obesity and Related Factors with Sleep- Related Breathing Disorders and Snoring in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health; 14(2): 194-200

- A Sánchez Armengol, A Ruiz García, C Carmona Bernal, G Botebol Benhamou, E García Díaz, et al. (2008) Clinical and polygraphic evolution of sleep-related breathing disorders in adolescents. Eur Respir J 32(4): 1016-1022.

- Rashid Nadeem, Janos Molnar, Essam M Madbouly, Mahwish Nida, Saurabh Aggarwal, et al. (2013) Serum inflammatory markers in obstructive sleep apnea: a meta- analysis. J Clin Sleep Med 9(10): 1003-1012.

- Li L, Chassan RA, Bruer EH, Gower BA, Shelton RC (2015) Childhood maltreatment increases the risk for visceral obesity. Obesity 23(8): 1625-1632.

- Macedo F, Dos Santos LS, Glezer I, da Cunha FM (2019) Brain Innate Immune Response in Diet-Induced Obesity as a Paradigm for Metabolic Influence on Inflammatory Signaling. Frontiers in neuroscience 13: 342.

- Dov B Ballak , Rinke Stienstra, Cees J Tack, Charles A Dinarello, Janna A van Diepen (2015) IL-1 family members in the pathogenesis and treatment of metabolic disease: Focus on adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. Cytokine 75(2): 280-290.

- JS Yudkin, M Kumari, SE Humphries, V Mohamed Ali (2000) Inflammation, obesity, stress and coronary heart disease: is interleukin-6 the link? Atherosclerosis 148(2): 209-214.

- TB Harris, L Ferrucci, RP Tracy, MC Corti, S Wacholder, et al. (1999) Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am J Med 106(5): 506-512.

- Sweatt SK, Gower BA, Chieh AY, Liu Y, Li L (2018) Sleep quality is differentially related to adiposity in adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 98: 46-51.

- Jennings JR, Muldoon MF, Hall M, Buysse DJ, Manuck SB (2007) Self-reported sleep quality is associated with the metabolic syndrome. Sleep 30(2): 219-223.

- Chaput JP, Despres JP, Bouchard C, Tremblay A (2007) Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin levels and increased adiposity: Results from the Quebec family study. Obesity 15(1): 253-261.

- Stern JH, Grant AS, Thomson CA, Lesley Tinker, Lauren Hale, et al. (2014) Short sleep duration is associated with decreased serum leptin, increased energy intake and decreased diet quality in postmenopausal women. Obesity 22(5): 55-61.

- Miller AL, Lumeng JC, Le Bourgeois MK (2015) Sleep patterns and obesity in childhood. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes and obesity 22(1): 41-47.

- Boeke CE, Storfer Isser A, Redline S, Taveras EM (2014) Childhood sleep duration and quality in relation to leptin concentration in two cohort studies. Sleep 37(3): 613-620.

- Li L, Fu J, Yu XT, Ge Li, , Lu Xu, et al. (2017) Sleep Duration and Cardiometabolic Risk Among Chinese School-aged Children: Do Adipokines Play a Mediating Role? Sleep 40(5): 1-9.

- Le Moult J, Kathryn L Humphreys, Alison Tracy, Jennifer Ashley Hoffmeister, Eunice Ip, et al. (2020) Meta-analysis: Exposure to Early Life Stress and Risk for Depression in Childhood and Adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 59(7): 842- 855.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, et al. (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14(4): 245-258.

- Kuczmarski R, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, KM Flegal, SS Guo, et al. (2000) CDC Growth Charts: United States. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics 8(314): 1-27.

- Chervin RD, Hedger K, Dillon JE, Pituch KJ (2000) Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness and behavioral problems. Sleep medicine 1(1): 21-32.

- Rundo JV, R Downey (2019) Polysomnography. Handb Clin Neurol 160: 381-392.

- Chen X, Beydoun MA, Wang Y (2008) Is sleep duration associated with childhood obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity 16(2): 265-274.

- Miller MA, Kruisbrink M, Wallace J, Ji C, Cappuccio FP (2018) Sleep duration and incidence of obesity in infants, children, and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep 41(4): 14-21.

- Cho HJ, Seeman TE, Kiefe CI, Lauderdale DS, Irwin MR (2015) Sleep disturbance and longitudinal risk of inflammation: Moderating influences of social integration and social isolation in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Brain, behavior and immunity 46: 319-326.

- Clinton JM, Davis CJ, Zielinski MR, Jewett KA, Krueger JM (2011) Biochemical regulation of sleep and sleep biomarkers. Journal of clinical sleep medicine 7(5): 38-42.

- Stacey Ishman, Christine Heubi, Todd Jenkins, Marc Michalsky, Narong Simakajornboon, et al. (2016) OSA screening with the pediatric sleep questionnaire for adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery in teen-LABS. Obesity 24(11): 2392- 2398.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.