Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Ageing and Increasing Doses are Factors Related to Delays for Adults with Haemophilia to Seek Prophylactic Clotting Factors

*Corresponding author: Ricardo Mesquita Camelo, Faculty of Medicine of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Rua Lorena, 1020, apto. 1102A. Belo Horizonte/MG, Brazil.

Received: April 16, 2021; Published: April 30, 2021

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2021.12.001789

Abstract

Adherence to prophylaxis influences the effectiveness of the haemophilia treatment. This retrospective single-centre cohort study aimed to identify factors related to delay to seek prophylactic factor for home treatment in people with severe and moderate haemophilia (PwHsm). Medical and pharmacy files were reviewed. A person who delayed ≤ 25% days to seek factor during a period of 12 scheduled dispensations was considered as adherent to seek the factor. Among 103 PwHsm, 53% were non-adherent to seek clotting factor. In the children/adolescents subgroup, delay was associated to haemophilia B. In the adult subgroup, both the age and the mean dose were directly associated with non-adherence. Children/ adolescents with haemophilia B delay longer to seek coagulation factors for prophylaxis, while adult PwHsm tend to delay with increasing age and increasing prophylactic dose to be infused. The interdisciplinary team should develop age-based strategies to ensure the patient will receive the prophylactic clotting factor at the scheduled time.

Keywords: Haemophilia; Prophylaxis; Delay Adherence; Age

Abbreviation: PwHsm: Person or people with Severe or Moderate Haemophilia; FVIII: Factor VIII; FIX: Fator IX; HA: Haemophilia A; HB: Haemophilia B; APT01: Adherence to Prophylactic Treatment-part 1; HTC: Haemophilia Treatment Centre; AsBR: Annualised Bleeding Rate; SD: Standard Deviation; IQR: Interquartile Range; RRadj: Adjusted Relative Risk; 95%CI: 95% Confidence Interval; VERITAS-Pro: Validated Haemophilia Regimen Treatment Adherence Scale-Prophylaxis

Introduction

Haemophilia is a rare X-linked bleeding disease characterized by a deficiency of the coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) or IX (FIX), known as haemophilia A (HA) or B (HB), respectively [1].The mainstem treatment of people with severe (factor activity less than 1%) or moderate (factor activity between 1% and 5%) haemophilia (PwHsm) with a bleeding phenotype is prophylaxis [1,2]. In prophylaxis, the deficient coagulation factor is administered regularly, avoiding breakthrough joint bleedings and guaranteeing musculoskeletal health and quality of life [2–5].

Since the PwHsm were co-responsible for their own treatment at home [6,7], adherence to the medication regimen has become the most important behaviour to achieve the prophylaxis success [8,9]. There are several methods to measure adherence to prophylaxis treatment, from direct methods which provide proof that the factor has been accordingly taken by the patient (i.e., blood factor activity), to indirect methods which can be categorized as selfreporting by the patient (i.e., validated questionnaires), medication measurement (i.e., vials count), use of electronic monitoring devices, and prescription record review [10,11]. Nevertheless, most of these methods cannot be blindly applied. Consequently, there is a subjective risk and/or actively patients’ interference on the results [11].

The Adherence to Prophylactic Treatment - part 1 (APT01) Study aimed to identify objective factors related to delaying seeking clotting factors for prophylaxis. The non-adherence to seek new prophylactic doses on the scheduled days was used as a non-adherence indirect measure to treatment, since it would indicate the lack of the product at home for a period beyond that was planned.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The study was a retrospective cohort. Patients were invited

during regular consultations at the Haemophilia Treatment

Centre (HTC) of Goias, in Goiania (Brazil), from 01/06/2016 to

06/31/2017. The inclusion criteria were

i) hereditary HA or HB;

ii) severe or moderate disease (plasma factor activity less than

1% or 1%-5%, respectively);

iii) negative inhibitor (inhibitor titre < 0.6 BU/mL);

iv) on home therapy with

v) prophylactic treatment [1]. Patients with positive inhibitor

(inhibitor titre ≥ 0.6 BU/mL) or those treated exclusively

on demand were excluded. The local Committee on Ethics

approved the study. All participants or their legal tutor signed

the Consent Form.

Patient Data

Demographic data included address, age, and educational status. The distance between the patient’s residence and the HTC was estimated from the respective addresses, considering the shortest distance calculated by Google Maps (www.google.com/ maps/search). Clinical data included patient weight at baseline, haemophilia type (HA or HB), treatment modality (primary or secondary prophylaxis), as well as the clotting factor regimen (dose and frequency), and the number of treated bleeding episodes. Primary prophylaxis was defined as regular infusions started before 36 months of age and before the second haemarthrosis; while secondary prophylaxis was defined as regular infusions started after 36 months of age or after the second haemarthrosis.1 Annualized bleeding rate (AzBR) was estimated by adjusting the total treated episodes during the respective observation period for a 12-month period.

Evaluation of the Adherence to Seek Prophylactic Factor in the Scheduled Visit

Data were obtained from the Pharmacy Department files, which is a part of the medical files. Data were reviewed from the inclusion date and backwards, until 12 dispensations for prophylaxis, which could occur before or after 12 months. The Pharmacy team was instructed to dispense all the prescribed doses and to guarantee a maximum of two additional doses at home, to treat breakthrough bleedings.

Clotting factor dispensation for home prophylaxis was regularly scheduled within 1 month, i.e., whenever the patient sought the product, the next appointment was scheduled within 30 days. However, the patient may have sought factor in advance or after the scheduled date. Based on this, an indirect strategy to measure non-adherence (delay) to seek the prescribed clotting factor was developed. The interval (in days) between one and a subsequent appointment was computed over each of the 12 dispensations [10,11]. The ratio Σ(days of advancement or delay)total ÷ Σ (days of interval)total was calculated to classify participants as adherent (average delay of 25% or less of follow-up days) and non-adherent to seek factor on a scheduled day.

The choice of 25% as a cut-off was based on two assumptions. Firstly, the number of infused doses on a regular-frequency regimen are directly proportional to the number of treatment days. We then corroborated with some authors who consider 25% of factor infusions as a non-adherence cut-off [9,12], extrapolating it to the delay to renew the home doses. Secondly, the patients usually received one or two additional doses to treat breakthrough bleedings. The renewal was conditioned to the return of the empty vials, guaranteeing the home storage of one or two vials in excess. Treating bleeding episodes at home can seldomly postpone seeking new doses, since it would occur in the days between the days of prophylactic infusion. Nevertheless, if the patient used the episodic dose as a prophylaxis, it would postpone the seeking about four to eight days, i.e., up to 25% of the days in a month.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using STATA, version 14.0. Continuous variables with normal distribution were described as mean and standard deviation (SD) and those with nonparametric distribution were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Qualitative variables were presented as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies.

Bivariate and multiple analyses were conducted to verify factors associated with non-adherence to the scheduled visit, i.e., delay to seek clotting factor (dependent variable). First, the groups (adherent vs. non-adherent to seek clotting factors for prophylaxis) were compared for sociodemographic, clinicallaboratory and therapeutic characteristics in the bivariate analysis. Differences between means or medians of quantitative variables between groups were assessed by Student’s t or Mann-Whitney U tests, respectively; difference between the qualitative proportions variables was verified by Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Robust variance Poisson regression model was built to analyse nonadherence predictors. Statistical modelling included variables with p-value < 0.20 in the bivariate analysis. The goodness-of-fit test was used to verify the model fit to Poisson regression. Results were expressed as adjusted relative risk (RRadj) and its respective 95% confidence interval (95%CI). In addition, sensitivity the results analysis was performed. Stratified (bivariate and multiple) factors analysis associated by age group (< 18 years and ≥ 18 years) was performed to verify the predictors in each age subgroup. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Population Characteristics

There were 353 registered PwH in the HTC, of whom 283 (283/353; 80%) were PwHsm. After excluding 132 patients in exclusive episodic treatment, 16 patients with inhibitor and 32 patients whose contact was lost, the study enrolled 103 (103/283; 36%) male PwHsm (95 PwHA being 83 PwHAs, and 8 PwHB being 5 PwHBs).

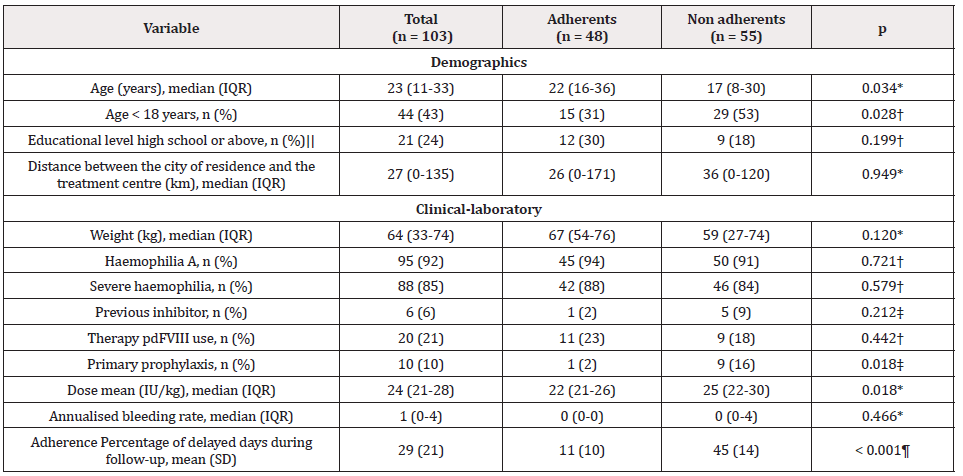

The general participants data were depicted on Table 1. The median (IQR) age of the participants was 23 (11-33) years and 21 (24%) had completed high school. The median distance (IQR) between the patient’s residence and the HTC was 27 (0-135) km. Ten patients (10%) were on primary prophylaxis. The prescribed regimen for PwHA ranged from 13 to 57 IU/kg for severe patients and 16 to 51 IU/kg for moderate patients, 2 to 3 times per week. PwHBs received 18 to 32 IU/kg and PwHBm received 16 to 40 IU/ kg, from 2 to 3 times a week.

Table 1: Characteristics of the patients with haemophilia, according to adherence to seek clotting factor concentrates for prophylaxis in a monthlyscheduled visit.

Note: IQR: Interquartile Range; pdFVIII: Plasma Derived Factor VIII; IU: International Unity; SD: Standard Deviation ||Estimated from 89 patients.

*Mann-Whitney U test; †Pearson’s χ2 test; ‡Fisher’s exact test; ¶Student’s t test for independent samples.

Delay to Seek Prophylactic Clotting Factors

The median (IQR) follow-up was 11 (11-11) intervals over a median (IQR) total period of 448 (392-586) days/patient. Eleven (11%) patients were not followed over 12 consecutive dispensations: 5, 3 and 3 patients were followed up until 11, 10 and 9 dispensations, respectively. The median total delay (IQR) for gathering the next prescribed factor was 118 (62-256) days/ patient, with a mean (± SD) delay of 29.1% ± 21.0% of the days of the year. Six (6%) patients sought clotting factor before the scheduled visit during the evaluated period. They were included in the adherent (no delay) group. There were 55 (53%) patients who delayed 25% or more days to seek factor on the scheduled visit during the follow-up period (Table 1).

Factors Associated with the Delay to Seek Clotting Factor for Prophylaxis

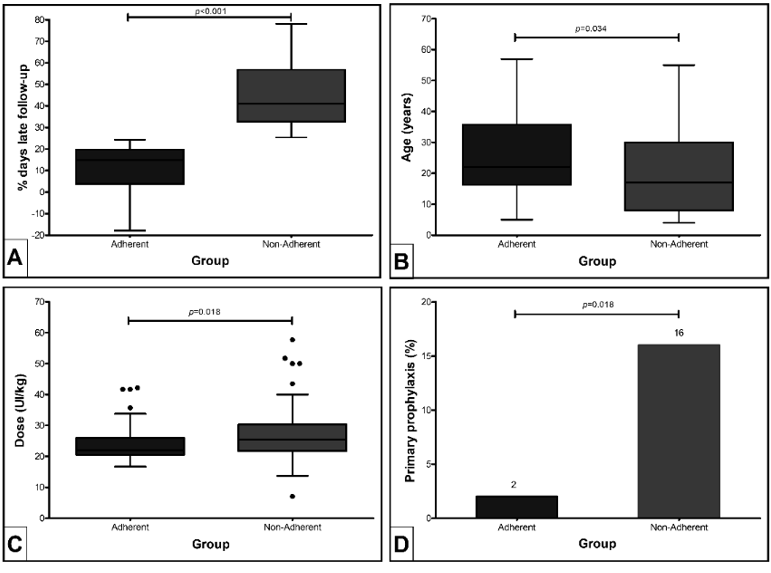

The mean (± SD) delay to seek procoagulant factor ranged from 11% ± 10% observation days (adherent group) to 45% ± 14% observation days (non-adherent group; p < 0.001). In the bivariate analysis, patients not adhering to the scheduled visit were younger (p = 0.034), received a higher mean dose of the prophylactic factor (p = 0.018), and had a higher proportion of primary prophylaxis (p = 0.018) compared to adherent patients (Table 1 & Figure 1).

Figure 1: Characteristics differences between people with haemophilia treated with prophylaxis who did not delay (adherent) and who delayed (non-adherent) to seek the clotting factor doses in a monthly-scheduled visit, in bivariate analysis (n = 103), according to (A) percentage of delayed days to seek factor, (B) age, (C) mean dose and (D) primary prophylaxis.

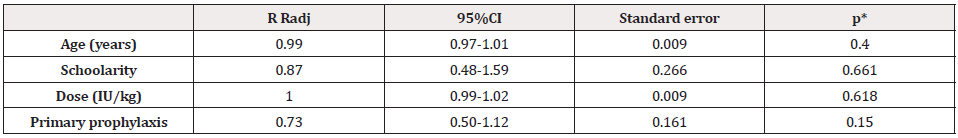

Table 2 summarizes the Poisson multiple regression model of factors associated with delay in the study population. Weight was highly correlated with age (r = 0.730), being excluded from modelling. The final model was adjusted for age, educational level, average dose, and type of prophylaxis. After adjustment, no variable was statistically associated with the study outcome (p > 0.05).

Table 2: Multiple regression analysis of factors associated with the delay to seek clotting factor concentrates for prophylaxis, according to the monthlyscheduled visit (n = 103).

Note: RRadj: Adjusted Relative Risk; 95%CI: Confidence Interval of 95%; IU: International Unity

*Statistics of Wald. Model adjusted by age, schoolarity, dose and prophylaxis; Pearson goodness-of-fit = 40.08; p = 1.000.

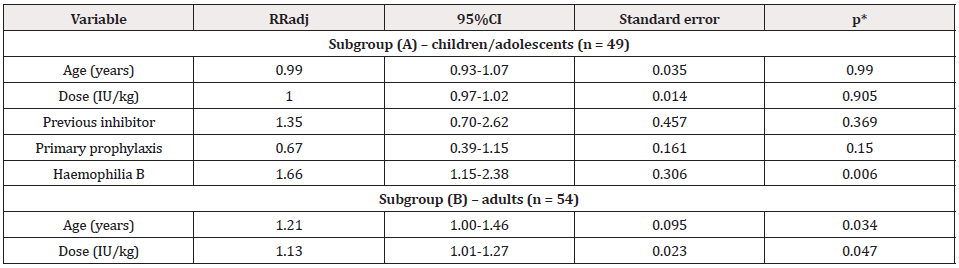

We next performed a stratified analysis of the associated factors by age group (<18 years as the children/adolescents subgroup, and ≥ 18 years as the adult subgroup). Variables with p-value < 0.20 in the bivariate analysis and age due to their potential for confusion were included in the respective models. Table 3 summarizes the final model of factors associated with delay in the children/adolescents (A) and for adults (B) subgroups. The model for children/adolescents was adjusted for age, dose, inhibitor background, prophylaxis modality, and haemophilia type. There was a statistically significant association between delay and HB (RRadj: 1.66; 95%CI: 1.15-2.38). In the analysis of the associated factors with delay in the adult subgroup, the model was adjusted only for age and dose. The mean age was associated with patient delay (RRadj: 1.21; 95%CI: 1.00-1.46; p = 0.034). There was also a positive association between increasing dose and delay to prophylactic treatment in this subgroup (RRadj: 1.13; 95%CI: 1.01- 1.27; p = 0.047).

Table 3: Multiple regression analysis of factors associated with non-adherence to seek clotting factor concentrates for prophylaxis in a monthlyscheduled visit, according to age subgroups: (A) children and adolescents (n = 49) and (B) adults with haemophilia (n = 54).

Note: RRadj: Adjusted Relative Risk; 95% CI: Confidence Interval of 95%; IU: International Unity

*Statistics of Wald. (A) Model adjusted by age, dose, previous history of inhibitor, type of prophylaxis and type of haemophilia; Pearson goodness-of-fit

= 16.91; p = 0.999. (B) Model adjusted by age, dose, previous history of inhibitor, type of prophylaxis and type of haemophilia; Pearson goodness-of-fit

= 27.02; p = 1.000.

Discussion

The APT01 Study evaluated the delay to seek the scheduled prophylactic factor as a proxy of adherence to treatment. The majority of PwHsm had HA, on a low-to-moderate dose regimen. Around half PwHsm delayed one week or more to seek prophylactic factor concentrates, according to the scheduled monthly visit. Among children/adolescents, the delay was related to having HB; while among adults, the delay was related to increasing age and increasing mean infused dose.

Factor replacement as prophylaxis is the standard treatment for PwHsm with a bleeding phenotype [1], since prophylaxis can prevent or stabilize joint deterioration, resulting in better quality of life [2–5]. However, patients should adhere to treatment, which means complying with the proposed intravenous regimen [8,9,13]. It requires an active involvement and a mutually acceptable behaviour course. We opted to use an indirect treatment adherence measurement, based on the protocol we follow to dispense clotting factor concentrates delay to seek prophylactic factor at a monthlyscheduled visit. Seeking factor at a regular scheduled basis would translate into being compliant and actively involved.

A useful and simple recommended method to evaluate adherence is a self-reported validated questionnaire [11]. The validation of the Brazilian version of VERITAS-Pro (Validated Haemophilia Regimen Treatment Adherence Scale-Prophylaxis) [14] was available one year after APT01 Study ended. The VERITASPro scores were moderately correlated with infusion log records and was weakly correlated with pharmacy dispensation records among Brazilian patients [15]. Another Brazilian study evaluated subjective and objective adherence to prophylaxis measures: participants’ self-perceived adherence and their number estimate of clotting factor concentrates that had been missed over the last period dispensation were compared with the proportion of vials returned/dispensed [16]. There was no significant correlation between self-perceived adherence degree (76%) and the objective adherence classification (31%) [16]. In addition, participants’ selfperceived adherence was 3 times more likely to be rated as “very good” or “good” than it was for the objective assessment. The authors proposed this could be the influence of social desirability bias in self-reported measures and different adherence concepts between patients/caregivers and haemophilia experts [16].

The patient interest, remembering and/or comprehension of the subject, which is being evaluated, can easily bias questionnaires and infusion records. However, the Pharmacy dispensation records are less prone to be biased, since dispensations are strictly controlled both by the HTC and the Brazilian Ministry of Health, which is responsible for the national purchase and distribution of clotting factor concentrates [17]. The current study was not designed to involve patient interviews, because we considered in advance that subjective adherence evaluation could be biased, as discussed by some authors [18].

Our results showed that distance between patient residence and HTC and educational level were not related to adherence. Although in some countries the adherence rate may be related to the economic factor [19], in Brazil the medication is entirely provided by the government [17]. Many patients residing far from the HTC have free transportation provided by their local government or the product is delivered to a healthcare service near their home. This may explain the lack of relationship between delays and distance from residence to HTC or educational level.

In the current literature, non-adherence to medication has been related to increasing age, especially among young adults [8,20]. This may be a low recognition consequence of the prophylaxis importance due to few bleeding experiences and stress caused by regular need of factor preparation and intravenous infusion, both during childhood, when adult tutors are responsible for treatment [21]. Besides that, prophylaxis during childhood is mainly practiced or coordinated by the parent, who guarantees the treatment [22]. As a result, prophylaxis during childhood would have greater adherence than prophylaxis during an older age [8,20]. Surprisingly, in APT01 Study, early age and primary prophylaxis were related to delay to seek prophylactic clotting factor in the univariate analysis. Some authors pointed out that lower adherence during childhood could be related to concerns such as school duties, shame of disease, physical activities limitation, and venous access challenges [23-25]. On the other hand, adherence-motivating factors among adolescents could be related to encouragement to take responsibility for selfcare and treatment participation [21,23]. However, the differences we found lost significance after the multivariate regression analysis.

We further evaluated possible factors for delaying seeking prophylactic clotting factor in each age subgroup. Children/ adolescents’ delay was related only to HB, but the sample size of PwHB was too small to be reliable. Among adult patients, delay was related to increasing age and increasing factor dose, corroborating some studies published so far [20,26]. This could be related to less frequent bleeding in adulthood, the treatment interference with daily activities, the inconvenience of performing multiple infusions, the inability to understand the therapy benefits, and the denial of the complications of the disease [23,27]. An important hallmark in the Brazilian treatment of haemophilia is that prophylaxis was an officially recommended therapy only after 2011 [28]. So, we believe adult PwHsm demonstrate less responsibility for their own treatment, due to a long period of treating only episodes with few short-term prophylaxis. It would justify why the older adult PwHsm delayed more days in seeking a clotting factor for prophylaxis than the younger adult PwHsm.

The only outcome evaluated in APT01 Study was AsBR. The number of haemorrhagic events measured is usually used as an outcome of prophylaxis adherence in some studies and some authors have observed a relation between increase in adherence to treatment and decrease in the bleeding rates [8,12]. Zanon et al. showed that prophylaxis adherence to prophylaxis was related to reduced bleeding and days lost at school or work, in parallel with improved performance in sports activities [9]. Therefore, the logical process would be prophylaxis adherence reduces joint bleedings, leading to musculoskeletal function improvement and a better quality of life. However, some studies could not confirm a relation between adherence and bleeding rates [22]. Thus, it is not possible yet to establish a true correlation, given the controversies among the authors. In addition, we could not find a relation between AsBR and adherence, maybe because the bleeding episodes happened too infrequently.

Practice Implications

The main factors that lead to better adherence to prophylaxis are generally linked to the interdisciplinary team good clinical practices. Nursing support is fundamental to start and maintain this behaviour [29], since this professional is constantly in close contact with the patient and the treatment centre team [30]. Therefore, comprehensive care for well-trained haemophilia promotes physical and psychosocial health, improves quality of life, and is associated with decreased morbidity and mortality [31]. The interdisciplinary team should develop age-based individual strategies to guarantee the patient will receive the clotting factor for prophylaxis at the scheduled time, to avoid breakthrough bleedings.

Limitations

The large sample size of PwHsm on home prophylaxis evaluated by a simple methodology based on objective computerized Pharmacy data is an important positive aspect of the APT01 Study. The objective method allowed a large number evaluation of PwHsm during a wide period. Nevertheless, the study has limitations. Firstly, the retrospective design did not enable us to evaluate subjective data about barriers and motivators for seeking the prophylactic factor. Secondly, we did not evaluate adherence to treatment using a direct methodology. This could not be performed in a retrospective trial, and it would probably increase the cost of the study, decreasing the number of enrolled patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, delay to seek clotting factor concentrates may be used as a tool to evaluate adherence to treatment. Furthermore, children/adolescents with HB delay longer to seek coagulation factors for prophylaxis, while adult PwHsm tend to delay with increasing age and increasing the prophylactic dose to be infused.

Conflict of Interest

MRFR has received scientific event grants from Hoffman-La Roche, Takeda and Novo Nordisk. CMCA received scientific event grants from Novo Nordisk. JMRLPC has received speaker fees from Novo Nordisk and scientific event grants from Takeda. RMC has received speaker/consultant fees and scientific event grants from Hoffman-La Roche and Takeda. AFMB, FCGS and RAG have no disclosures to declare.

References

- Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser Bunschoten EP, Key NS, Kitchen S, et al. (2013) Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia 19(1): e1‐e47.

- Manco Johnson MJ, Soucie JM, Gill JC (2017) Prophylaxis usage, bleeding rates, and joint outcomes of hemophilia, 1999 to 2010: A surveillance project. Blood 129(17): 2368-2374.

- Manco Johnson MJ, Abshire TC, Shapiro AD, Riske B, Hacker MR, et al. (2007) Prophylaxis versus Episodic Treatment to Prevent Joint Disease in Boys with Severe Hemophilia. N Engl J Med 357(6): 535-544.

- Gupta S, Siddiqi AEA, Soucie JM, Manco Johnson M, Kulkarni R, et al. (2013) The effect of secondary prophylaxis versus episodic treatment on the range of motion of target joints in patients with haemophilia. Br J Haematol 161(3): 424-433.

- Tagliaferri A, Feola G, Molinari AC, Santoro C, Rivolta GF, et al. (2015) Benefits of prophylaxis versus on-demand treatment in adolescents and adults with severe haemophilia A: the POTTER study. Thromb Haemost. 114(1): 35-45.

- Schrijvers LH, Beijlevelt Van Der Zande M, Peters M, Schuurmans MJ, Fischer K (2012) Learning intravenous infusion in haemophilia: Experience from the Netherlands. Haemophilia. 18(4): 516-520.

- Hoefnagels JW, Kars MC, Fischer K, Schutgens REG, Schrijvers LH (2020) The perspectives of adolescents and young adults on adherence to prophylaxis in hemophilia: A qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence 14: 163-171.

- Krishnan S, Vietri J, Furlan R, Duncan N (2015) Adherence to prophylaxis is associated with better outcomes in moderate and severe haemophilia: Results of a patient survey. Haemophilia 21(1): 64-70.

- Zanon E, Tagliaferri A, Pasca S, Ettorre CP, Notarangelo LD, et al. (2020) Physical activity improved by adherence to prophylaxis in an Italian population of children, adolescents and adults with severe haemophilia A: the SHAPE Study. Blood Transfus. 18(2): 152-158.

- Lima Dellamora EC, Osorio de Castro CGS, Madruga LGSL, Azeredo TB (2017) Utilização de registros de dispensação de medicamentos na mensuração da adesão: Revisão crítica da literature. Cad Saude Publica. 33(3): 1-16.

- Anghel LA, Farcas AM, Oprean RN (2019) An overview of the common methods used to measure treatment adherence. Med Pharm Reports. 92(2): 117-122.

- Pérez Robles T, Romero Garrido JA, Rodriguez Merchan EC, Herrero Ambrosio A (2016) Objective quantification of adherence to prophylaxis in haemophilia patients aged 12 to 25 years and its potential association with bleeding episodes. Thromb Res. 143: 22-27.

- Schrijvers LH, Cnossen MH, Beijlevelt van der Zande M, Peters M, Schuurmans MJ, et al. (2016) Defining adherence to prophylaxis in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 22(4): e311-e314.

- Duncan NA, Kronenberger W, Roberson C, Shapiro A (2010) VERITAS-Pro: A new measure of adherence to prophylactic regimens in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 16(2): 247-255.

- Ferreira AA, Leite ICG, Duncan NA (2018) Validation of the Brazilian version of the VERITAS-Pro scale to assess adherence to prophylactic regimens in hemophilia. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 40(1): 18-24.

- Guedes VG, Thomas S, Wachholz PA, Souza SAL (2018) Challenges and perspectives in the treatment of patients with haemophilia in brasil. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 64(10): 872-875.

- Ministerial Decree (1980) Approval of basic guidelines of the National Program of Blood and Blood Products (Pró-Sangue). Diário Of da União. 1: 8226.

- Thornburg CD, Carpenter S, Zappa S, Munn J, Leissinger C (2012) Current prescription of prophylactic factor infusions and perceived adherence for children and adolescents with haemophilia: a survey of haemophilia healthcare professionals in the United States. Haemophilia. 18(4): 568-574.

- Li Z, Wu J, Zhao Y, Liu R, Li K, et al. (2018) Influence of medical insurance schemes and charity assistance projects on regular prophylaxis treatment of the boys with severe haemophilia A in China. Haemophilia. 24(1): 126-133.

- Witkop ML, McLaughlin JM, Anderson TL, Munn JE, Lambing A, et al. (2016) Predictors of non-adherence to prescribed prophylactic clotting-factor treatment regimens among adolescent and young adults with a bleeding disorder. Haemophilia. 22(4): e245-e250.

- Young G (2012) From boy to man: recommendations for the transition process in haemophilia 18: 27-32.

- Schrijvers LSH, Beijlevelt van der Zande M, Peters M, Lock J, Cnossen MH, et al. (2016) Adherence to prophylaxis and bleeding outcome in haemophilia: a multicentre study. Br J Haematol 174(3): 454-460.

- Schrijvers LH, Kars MC, Beijlevelt van der Zande M, Peters M, Schuurmans MJ, et al. (2015) Unravelling adherence to prophylaxis in haemophilia: A patients’ perspective. Haemophilia 21(5): 612-621.

- Bérubé S, Cloutier Bergeron A, Amesse C, Sultan S (2017) Understanding adherence to treatment and physical activity in children with hemophilia: The role of psychosocial factors. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 34(1): 1-9.

- Mason JA, Parikh S, Tran H, Rowell J, McRae S (2018) Australian multicentre study of current real-world prophylaxis practice in severe and moderate haemophilia A and B. Haemophilia 24(2): 253-260.

- Duncan N, Shapiro A, Ye X, Epstein J, Luo MP (2012) Treatment patterns, health-related quality of life and adherence to prophylaxis among haemophilia A patients in the United States. Haemophilia 18(5): 760-765.

- Miesbach W, Kalnins W (2016) Adherence to prophylactic treatment in patients with haemophilia in Germany. Haemophilia. 22(5): e367-e374.

- Ferreira A, Leite I, Bustamante Teixeira MT, Guerra M (2014) Hemophilia A in Brazil - epidemiology and treatment developments. J Blood Med. 23(5): 175‐184.

- Lock J, Raat H, Peters M, Scholten M, Beijlevelt M, et al. (2016) Optimization of home treatment in haemophilia: effects of transmural support by a haemophilia nurse on adherence and quality of life. Haemophilia 22(6): 841-851.

- Pai M, Key NS, Skinner M, Curtis R, Feinstein M, et al. (2016) NHF-McMaster Guideline on Care Models for Haemophilia Management. Haemophilia. 22: 6-16.

- Gue D, Squire S, McIntosh K, Bartholomew C, Summers N, et al. (2015) Joining the patient on the path to customized prophylaxis: One hemophilia team explores the tools of engagement. J Multidiscip Healthc 8: 527-534.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.