Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Proof on Concept on the Consumption of a Beverage with Ancestral Mexican Corn and Bean Flour and its Cardiometabolic Effects on Adolescents with Obesity

*Corresponding author: Gabriela Gutiérrez-Salmeán, Centro de Investigación en Ciencias de la Salud, Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Anáhuac México, Tel: +52 55 2898 6740, México

Received: April 06, 2021; Published: April 21, 2021

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2021.12.001773

Abstract

Background: Obesity rates have increased in recent years throughout Mexican adolescents. Obesity is associated with the development of cardiometabolic disruptions as low-grade chronic inflammatory pathways are activated. The cornerstone therapeutics includes dietary management; within, functional foods may be considered as co-adjuvants due to their bioactive components, which can modulate the underlying metabolic pathways. Among these foods are beans and corn, which contain anthocyanins, and they have been associated with the reduction of cardiometabolic diseases.

Methods: A proof of concept study was performed, incorporating a beverage with ayocote bean and chapalote corn, in order to evaluate its impact on the cardiometabolic profile of adolescents with obesity.

Results: After 12 weeks of dietary treatment and corn/bean supplementation, no statistically significant differences were found neither on anthropometric nor biochemical parameters after intra- and intergroup evaluation. We, in contrast, observed a surprisingly low adherence to medical and nutritional treatment, as well as the lack of commitment from the patient and his family environment towards health.

Conclusions: Although more research is required on the use of ancestral functional foods to modulate the cardiometabolic profile of adolescents with obesity, it is important to raise awareness about the magnitude of excess weight and the comorbidities associated in our country, and the importance of having an adequate attachment to the comprehensive treatment of obesity.

Keywords: Ancestral functional foods, Ayocote bean, Chapalote corn, Adolescent obesity, Cardiometabolic profile

Introduction

Obesity is a major public health problem worldwide that also affects adolescents in our country, with a combined prevalence of 38.4% according to data from the 2018 National Health and Nutrition Survey [1]. Therefore, its prevention and treatment are relevant since it is considered the second preventable cause of death after smoking and, in addition, it is estimated that overweight adolescents have a 40 to 70% risk of being adults with obesity [2,3]. Obesity is defined as the disease characterized by excess adipose tissue in the body in which there is an imbalance between intake and energy expenditure and develops as a consequence of genetic, social, psychological and metabolic factors, causing chronic inflammation of low grade [4,5]. This inflammatory state is associated with comorbidities that increase cardiometabolic risk, such as insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, high blood pressure and fatty liver disease, which start from early stages of life [6].

Treatment for obesity and its underlying disorders, changes in lifestyle and diet are implemented to decrease the relationship between intake and energy expenditure. As part of dietary modifications, a decrease in the intake of sugars and saturated fats has been recommended, as well as an increase in fruits and vegetables, which contribute to the reduction of the energy density of food [7,8]. Within the diet, it is also possible to include functional foods, which have the characteristic that they not only have nutritional components, but also provide other components that favor the health, physical and mental state of the person who consumes them [9]. In Mexican traditional gastronomy there is a wide variety of functional foods such as chili pepper, cocoa, and the different varieties of corn and beans, which contain bioactive compounds such as polyphenols. The bioactive molecules are divided into flavonoids, phenolic acids, lignans and stilbenes, with flavonoids being the group most studied until now [10,11]. Within this group are anthocyanins, which are water-soluble pigments responsible for giving bright blue, red and purple colors to plants, fruits, and some cereals, such as in the case of ancestral (i.e., part of the traditional diet since prehispanic times but nowadays not frequently consumed due to margination as they are not widely commercial even though accessible) maize and beans [12,13].

Corn is the main cereal consumed in Mexico commonly in the form of tortilla, however, there are different types of corn that provide great health benefits for its rich content of antioxidants and anthocyanins, such is the case of chapalote corn, with its characteristic red color due to its phenolic content [14,15]. Beans, for its side, are another of the main components of the Mexican diet, with around 70 varieties among which is the ayocote bean, characterized by its purple color because of its anthocyanin content [16,17]. Different studies have identified the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of anthocyanins through the inhibition of NF-κB, the reduction of reactive oxygen species, the decrease of low-density cholesterol (LDL), the prevention of obesity and insulin resistance [12,18].

Materials and Methods

This study complies with the guidelines stipulated in the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, in the Declaration of Helsinki [19] and the Nuremberg Code [20], as well as NOM-012-SSA3-2012 [21]. This work was approved by the Research Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the Universidad Anáhuac México Norte (reg. 201848) and accepted and registered by the Research Committee of the Hospital Regional Lic. Adolfo López Mateos (RPI. 492.2018, 029/AE/I/2018).

Patients were recruited from Hospital Regional Lic. Adolfo López Mateos and invited to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were both sexes, between 12 and 18 years of age, with abdominal obesity, Tanner 2 to 4 and use of metformin as treatment for cardiometabolic disease. After signing the informed consent and assent, patients were randomly allocated into one of two doubleblinded groups: control or experimental. The first group received placebo (drink with white corn and bay bean, 50 gr) and the second one a drink with chapalote corn and ayocote bean (50 gr, 100 mg of gallic acid equivalents), both orally, as a part of the breakfast, every 24 hours for 12 weeks.

Anthropometric measurements (weight, height, waist circumference, body fat percentage, muscle mass) and blood pressure were registered, and further the body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-height ratio was calculated. A blood sample was collected to determine the levels of glucose, triglycerides, insulin, HDL cholesterol, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) in serum, and further HOMA and TG/HDL indexes were calculated. For measuring the weight and body fat percentage a bioelectric impedance scale was used, for the height a wall stadiometer, for waist circumference a metal tape, for collecting the blood pressure a digital arm baumanometer, finally the glucose and lipids samples were performed by spectrophotometry, glycated hemoglobin by high performance liquid chromatography, and insulin by chemiluminescence [22-24].

An individualized eating plan also was prescribed to each patient calculating their energy requirement according to the Schofield equation [25]. Patients were monitored twice again (at 4 and 8 weeks), measuring anthropometric features and blood pressure. At the end of the period, the blood sample, anthropometric variables and blood pressure were obtained again.

Statistical Analysis

The variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation;categorical variables were expressed as frequencies. Subsequently, an intragroup analysis was carried out with ANOVA for repeated samples. Intergroup comparison was made with t-Student for independent samples. p<0.05 was considered as statistical significance. All the above was done using version 5 of the GraphPad Prism software.

Results

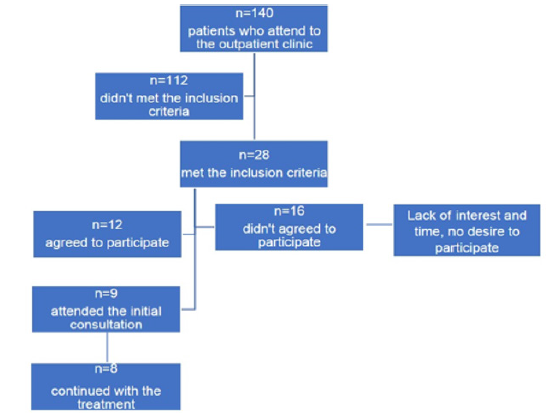

From November 2018 to August 2019, 140 patients who attended the Nutrition-Pediatrics outpatient clinic at the Hospital Regional Lic. Adolfo López Mateos were screened. Of these, 28 (i.e., 20%) met the established inclusion criteria, however, 16 (i.e., almost 6 out of 10) did not agree to participate for various reasons, the most common being lack of interest and “lack of time” to attend consultations both by the school for work commitments from parents or guardians. 12 patients agreed to participate, but only 9 attended the initial consultation, and of these, 8 continued with the treatment. The patient who did not continue after the first consultation returned several weeks later, saying that she no longer desired to continue participating.

The above are summarized in (Figure 1).

Figure 1: CONSORT flow diagram. This figure shows the flow of patients through the trial according to the criteria recommended in the CONSORT.

Baseline characteristics

In total, the study protocol was completed by 8 patients, of which 5 were men (62.5%) and 3 women (37.5%), with a mean age of 13.5 ± 4.78 years and whose baseline characteristics are detailed in (Table 1). All patients had a BMI >95th percentile thus indicating obesity; they also had a waist-to-height ratio >0.50, implying an increased risk of developing cardiometabolic diseases [26,27]. 50% had mixed dyslipidemia, with serum triglycerides above 130 mg/dL (cut-off point for the 10-19 age group), and HDL-c less than 50 mg/dL [28]. This yielded a TG/HDL index >4.5 in 37.5% of patients, which also indicates that the population is at high risk of presenting cardiometabolic diseases [29,30]. Blood pressure was within normal percentiles for age, height, and sex, in all patients so it was decided that it was not considered a cardiometabolic factor to be analyzed hereinafter.

Overall results

As detailed in the methodological section, patients received an individualized dietary plan calculated with the Schofield formula with adjusted weight and height, with a distribution of carbohydrates of 40-60%, lipids of 30-35% and protein of 10- 20%. The beverage was included within such plan. Results of the evolution of the anthropometric variables of the complete sample during the 3-mo intervention are presented in (Table 2).

observed in the previous table, a statistically significant difference was only found in waist circumference at the eighth week of treatment and, in fact, the following month, it was recovered. Linked to this, a trend in fat loss was observed, which could indicate that, if the treatment were prolonged, a statistically significant decrease in fat would be observed. Table 3 presents serum analytes: as shown, no changes were found except for a statistically significant difference in HbA1c, revealing that despite receiving medical-nutritional treatment, there was no improvement, quite the opposite. Furthermore, all the other indicators, although they do not reach statistical significance, the trend is towards increasing them, thereby increasing the cardiometabolic risk of the patients.

Results by groups

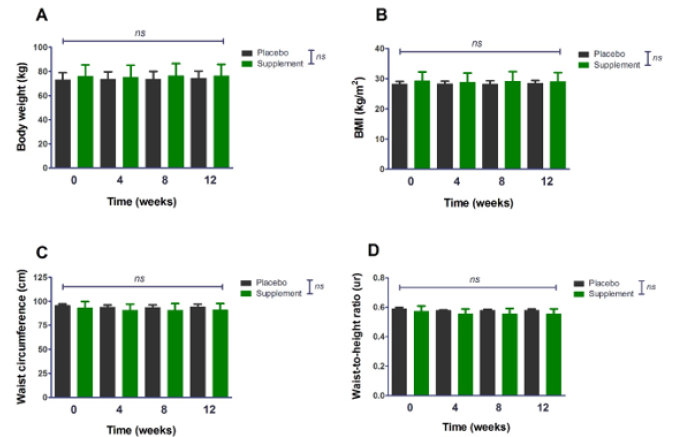

Figure 2: Analysis of anthropometric indicators by group (t-Student for independent samples) and throughout the treatment period (ANOVA for repeated measures). BMI: body mass index.

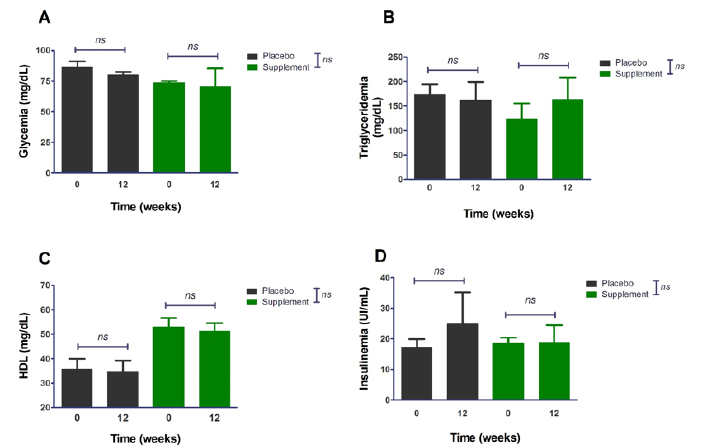

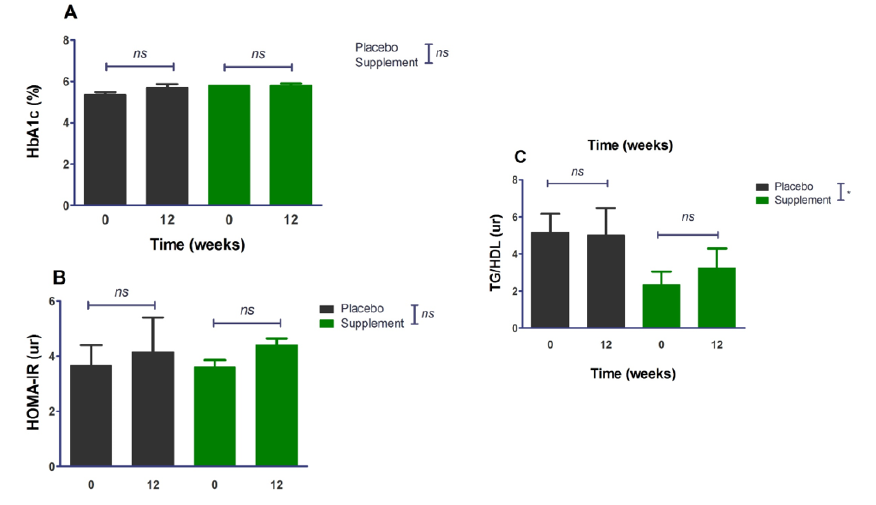

Upon opening the blinding, each group was made up of 4 individuals. The results of the intra- and intergroup evaluations are presented below in (figure 2). As observed in the previous figure, no statistically significant change was found over the 12 weeks in any group and, consequently, there was no difference between them either. By separating the groups, the sample size decreases, and with this, the dispersion of the data increases, unlike the global analysis, in which the number of patients increases and the standard deviation decreases. Regarding the biochemical aspects, there was also no improvement in the fasting indicators as shown in figure 3; therefore, no improvement and differences were found in cardiometabolic risk indexes (i.e., focus on the chronic phenomenon) as is can be observed in figure 4. *A statistically significant difference is observed in the TG/HDL index between the supplement/placebo groups since the supplement group includes 2 patients with lower triglyceride values compared to the rest of the values, just as in the placebo group there is a patient with a higher triglyceride value compared to the rest of the patients.

Discussion

Obesity is a multifactorial and highly prevalent disease in Mexico, which has been identified as a risk factor for various comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, dyslipidemias, osteoarthritis, depression and cancer. Furthermore, in cases of extreme obesity, life expectancy could decrease between 6 and 14 years [31,32]. In the present study it was possible to observe that the patients have both anthropometric and biochemical alterations: obesity (i.e., being above the 95th percentile of BMI for age), with a waistheight index greater than 0.5, which increases the cardiometabolic risk due to excess adipose tissue, mainly visceral [26,27]. This latter is of the most relevance as initial average of 0.58 ± 0.04 did not significantly change (final value of 0.56 ± 0.04) after 3-mo treatment and values remained as high cardiometabolic risk. For its side, fat mass percentage, despite showing a tendency to decrease, persisted in very high figures, even for the adult population [33]. This excessive accumulation of fat increases the inflammatory state, and with it, the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, PCR, IL-6, PAI-1, which contribute to the state of lowgrade chronic inflammation hence persisting the risk of developing and/or exacerbating comorbidities such as insulin resistance, high blood pressure and dyslipidemias [34-36], as seen in these patients.

During puberty, physiological insulin resistance occurs, however, ectopic fat deposition leads to dysfunction of pancreatic β cells [37,38]. Initially, pancreatic β cells increase insulin production with the aim of compensating for insulin resistance and, thus, blood glucose remains at normal levels [38]. It is possible to observe that the patients present baseline insulinemia of 18.91 ± 2.64 μU/ml and final of 23.33 ± 13.68 μU/ml, in both cases, above the reference values of 14.38 μU / ml [39]. In correspondance, an initial HOMA index of 3.62 ± 0.61 and final of 5.18 ± 2.43, indicated high risk of insulin resistance [24,37]. This insulin resistance is also a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and, together with obesity, increases the risk of developing dyslipidemias [38,40].

Similarly, the pathophysiological mechanism of hypertriglyceridemia is observed, in which high triglyceride levels, together with the increase in VLDL concentrations, provide triglycerides to LDL and HDL particles in exchange for cholesterol esters, causing the HDL particles are more susceptible to being degraded, increasing the risk of presenting atherogenic dyslipidemia, and with it, a higher cardiovascular risk [41,42]. The increase in triglycerides contributes to their contribution to HDL particles, causing greater purification of the same. In this way, it is possible to observe the dyslipidemia characteristic of the metabolic syndrome, hypertriglyceridemia and decrease in serum HDL levels [41].

According to the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP), for adolescents, triglycerides are considered to be elevated when they are equal to or greater than 130 mg/dL, and HDL is considered low when it is less than 40 mg/dL. In the present study, the patients had an initial triglyceridemia average of 148.4 ± 57.22 mg/dL and a final concentration of 161.9 ± 77.09 mg/dL; for its side and despite the fact that the average HDL is 44.38 ± 11.72 mg/dL and 43 ± 11.45 mg/dL, respectively, individual values reach down to 30 mg/dL, evidencing the pathophysiology of dyslipidemia [28]. In a study in Mexico, the characteristics of school and adolescent patients with obesity were described, in which it was reported that they presented a HOMA index of 3.23 ± 2.19 40, similar to the baseline characteristics of the present sample. Another study is South America with population with obesity between 10 and 18 years old, with and without insulin resistance, found that those patients without insulin resistance had a HOMA of 1.8 and a TG/ HDL ratio of 1.69, while those Insulin resistance patients had 4.5 and 2.28, respectively [43]. These data do not resemble those obtained in the present study, since the TG/HDL index is lower than that presented by our patients.

On the other hand, also in the lipid aspect, it has been suggested that a TG/HDL index of ≥3 is associated with higher concentrations of small LDL particles, which increases cardiovascular risk as they are atherogenic particles [30]. The TG/HDL index not only speaks of cardiovascular risk but is also related to insulin secretion and sensitivity 37, and it was possible to observe that the average value of this index was, initially, 3.76 ± 2.19, and finally, 4.12 ± 2.54, in both cases, above the proposed cut-off point. In Mexico, a study was carried out in which children from 5 to 9 years of age participated, it was identified that those with a TG/HDL index ≥1.71, presented 3 times more risk of having high LDL, this being an important risk factor cardiometabolic [44]. A study done in the United States in adolescents with a mean age of 13.1 ± 2.9 years, found, in the Hispanic population, a mean TG/HDL of 3.41 ± 3.09 in men and 3.00 ± 2.29 in women, and at the time of dividing this index in tertiles, a HOMA of 6.38 ± 4 in the lowest tertile and 9.65 ± 5.2 in the highest tertile [45]. Another study in Malaysia, with overweight and obese patients between 9 and 16 years old, showed within the characteristics of the population that they had an HbA1c of 5.2% and TG/HDL. Specifically, the mean TG/HDL in patients with insulin resistance was 2.48 and the highest tertile was 3.1, with these values being lower than what was found in the present study [46].

We were most surprised by the fact that neither patients nor their families show commitment to carrying out the actions that decrease this inflammatory state (i.e., compliance to dietary prescription, regular exercising, no consumption of ultra-processed foods, etc.). Since screening, more than half (57.1%) of patients decided not to participate for various reasons, including lack of “interest in the study protocol” and/or lack of time to attend consultations within the study. Now, of those patients who met selection criteria and initially agreed to participate, only 75% attended the initial consultation, and finally 89% of those completed the study yielding a total of 8 patients. Among the patients who completed the study, some reported difficulty in maintaining the indicated dietary treatment due to causes such as “boredom” and incompatibility with family activities. This reflects the lack of commitment on the part of the patient and his family, as well as the difficulty of the health personnel to maintain the motivation and commitment of the adolescents. It was fairly clear that the magnitude of the disease and its comorbidities is not well-dimensioned since both the patients and their relatives do not consider the presence of obesity as an important factor of morbidity and mortality and the relevance of having an adequate adherence to nutritional treatment.

However, our findings actually concord with other such as the study of Nogueira and Zambon, who reported that among the barriers that made it difficult for patients to adhere to their obesity management were the lack of time to go to consultations, since adolescents had to miss school and parents to work; patients refusal to continue treatment; dissatisfaction with the results achieved; that parents could not deny food to their children and that they had no control over their diets. Furthermore, they highlighted the fact that although the parents knew the risk of developing comorbidities associated with obesity, this did not represent a stimulus to continue treatment [47].

Regarding nutritional indications, it was reported that few patients had difficulty understanding them, however, most presented difficulties in carrying them out [47]. In addition, it should be noted that the results not only indicate lack of adherence to nutritional treatment and eating plan, but there is also a lack of adherence to medical treatment, since despite the fact that the patients were under metformin management no statistically significant difference was observed regarding biochemical parameters in the 3 months of intervention. A meta-analysis that aimed to assess the effect of metformin on the HOMA index, fasting glucose and insulin, HDL and LDL, in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity, reported that metformin could improve LDL levels but did not have a significant effect on insulin resistance. Furthermore, it was observed that some patients abandoned the different studies due to lack of interest, loss of contact, or refusal to participate [48]. Another study evaluating the efficacy, tolerability and safety of metformin in adolescents with obesity and insulin resistance, found that, during the first months of treatment, there was a decrease in BMI and HOMA, however, it was not possible to observe the same long-term result secondary to factors such as low adherence to treatment and the possible low doses indicated [49]. Finally, a pilot study with patients between 6 and 13 years of age with obesity, who were given metformin or placebo, reported a decrease in BMI, fat mass, serum leptin levels and CRP. However, no decrease in the HOMA index was observed, probably due to the low insulin resistance status of the patients. The study methodology shows that 6 patients in the metformin group refused to continue, and 2 in the placebo group abandoned the study due to low attachment [50].

All this takes relevance since there is a high risk that patients presenting obesity and cardiometabolic disorders from childhood and adolescence present early comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic liver steatosis, obstructive sleep apnea, some types of cancer, kidney disease, polycystic ovary syndrome; which translates into an epidemiological risk, which, in the long term, will collapse the health system [30,51,52].

Conclusions

No significant differences were found on cardiometabolic markers of adolescents with obesity after consuming a drink based on ancestral Mexican maize and bean (chapalote corn and ayocote beans, respectively) for 12 weeks. The most relevant fact herein found is that patient’s compliance is minimal thus therapeutic efficacy is almost null, therefore, urgent measures regarding health staff’s abilities, patients’ and their family’s commitment on medical-nutrition treatment and, moreover, their awareness on the importance of the diseases they are currently undergoing as well as their future complications. In addition, monitoring by psychology is essential, since it allows working the emotional area of the patients and the support network they have at home and being able to give a completely individualized treatment.

Study Limitations

Sample size was very small thus inferential (particularly grouped) analysis is probably limited. Some modifications to the protocol can be considered for future research, e.g., reducing the age range hence considering not only adolescents but scholar individuals in order to increase screening and further recruitment/ sample size. Furthermore, the inclusion of children with obesity already in pharmacologic treatment (additional to metformin) for comorbidities should be considered.

Acknowledgements

RKA, JALI and GGS conceived and carried out experiments; RKA and JALI carried out the clinical interventions; MHO elaborated and provided supplement/placebo; RKA, MHO and GGS analysed data; RKA and GGS wrote the manuscript sketch. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

References

- Romero-MM, Shamah-LT, Vielma-OE (2019) Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018-19: informe de resultados. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pú

- Alfonso-Guerra JP (2013) Obesidad. Rev Cub Salud Publica 39(3):424-425.

- Liria R (2012) Consecuencias de la obesidad en el niño y el adolescente: un problema que requiere atenció Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica 29(3): 357-360.

- Prevención, Diagnóstico y (2012) Tratamiento del Sobrepeso y la Obesidad Exó México, Secretaría de Salud, Actualización.

- (2018) NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-008-SSA3-2017, Para el tratamiento integral del sobrepeso y la obesidad. Diario Oficial de la Federación, Mexico.

- Di Domenico M, Pinto F, Quagliuolo L, Maria C, Giuliana S, et al. (2019) The Role of Oxidative Stress and Hormones in Controlling Obesity. Front Endocrinol 10: 540.

- DeBoer MD (2019) Assessing and Managing the Metabolic Syndrome in Children and Adolescents. Nutrients 11(8): 1788.

- Naseri R, Farzaei F, Haratipour P, Seyed FN, Solomon H, et al. (2018) Anthocyanins in the Management of Metabolic Syndrome: A Pharmacological and Biopharmaceutical Review. Front Pharmacol 9: 1310.

- Alvídrez-Morales A, González-Martínez BE, Jiménez-Salas Z (2002) Tendencias en la producción de alimentos: alimentos funcionales. RESPYN 3(3): 1-7.

- Konstantinidi M, Koutelidakis A (2019) Functional Foods and Bioactive Compounds: A Review of Its Possible Role on Weight Management and Obesity’s Metabolic Consequences. Medicines (Basel) 6(3): 94.

- Tomás-Barberán FA (2003) Los polifenoles de los alimentos y la salud. Alim. Nutri. Salud 10(2): 41-53.

- Tomay F, Marinelli A, Leoni V, Claudio Caccia, Andrea Matros, et al. (2019) Purple corn extract induces long ‑ lasting reprogramming and M2 phenotypic switch of adipose tissue macrophages in obese mice. J Transl Med 17(1): 237.

- Teng H, Chen L (2019) Polyphenols and Bioavailability: An Update. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 59(13): 2040-2051.

- Lopez-Martínez LX, Oliart-Ros RM, Valerio-Alfaro G, Chen-HL, Kirk P, et al. Antioxidant activity, phenolic compounds and anthocyanins content of eighteen strains of Mexican maize. LWT-Food Sci Technol 42(6): 1187-1192.

- Perales Rivera H, Golicher D (2011) Modelos de distribución para las razas de maíz en México y propuesta de centros de diversidad y de provincias bioculturales: informe té CONABIO.

- (2016) Dirección de Investigación y Evaluación Económica y Sectorial. Panorama Agroalimentario- Frijol 2016. FIRA.

- (2019) Dirección de Investigación y Evaluación Económica y Sectorial. Panorama Agroalimentario- Frijol 2019. FIRA.

- Rocha DMUP, Caldas APS, da Silva BP, Helen HMH, Rita de CGA, et al. (2019) Effects of Blueberry and Cranberry Consumption on Type 2 Diabetes Glycemic Control: A Systematic Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 59(11): 1816-1828.

- (1964) Asociación Médica Mundial. Declaración de Helsinki.

- (1947) Tribunal Internacional de Nuremberg. Código de Nuremberg.

- (2013) NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-012-SSA3-2012, Que establece los criterios para la ejecución de proyectos de investigación para la salud en seres humanos. Diario Oficial de la Federación, (04-Ene-2013).

- Velázquez Salgado R (2009) Manual de Prácticas Bioquímica Clí México: pp160.

- Campuzano-MG, Latorre-Sierra G (2010) La HbA1c en el diagnóstico y en el manejo de la diabetes. Med Lab 16(5-6): 211-241.

- Peña-Espinoza BI, Granados-Silvestre MA, Sánchez-Pozos K, Katy SP, bMaría GO-L, et al. (2017) Síndrome metabólico en niños mexicanos: poca efectividad de las definiciones diagnó Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr 64(7): 369-376.

- Becerril-Sánchez ME, Flores-Reyes M, Ramos-Ibáñez N, Luis Ortiz-Hernández (2015) Ecuaciones de predicción del gasto de energía en reposo en escolares de la Ciudad de Mé Acta Pediatr Mex 36(3): 147-157.

- Valle-Leal J, Abundis-Castro L, Hernández-Escareño J, et al. (2016) Índice Cintura-Estatura Como Indicador De Riesgo Metabólico En Niñ Rev Chil Pediatr 87(3): 180-185.

- Hernández RJ, Duchi JPN (2015) Índice cintura/talla y su utilidad para detectar riesgo cardiovascular y metabó Rev Cuba Endocrinol 26(1): 66-76.

- (2012) US Department of Health and Human Services. Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents: Summary Report. National Institutes of Health.

- Baez-Duarte BG, Zamora-Gínez I, González-Duarte R, Enrique TR, Guadalupe R-V, et al. (2017) Triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (TG/HDL-C) index as a reference criterion of risk for metabolic syndrome (MetS) and low insulin sensitivity in apparently healthy subjects. Gac Med Mex 153(2): 152-158.

- Wittcopp C, Conroy R (2016) Metabolic Syndrome in Children and Adolescents. Pediatr Rev 37(5): 193-292.

- Brito-Núñez NJ, Alcázar Carett RJ (2011) Obesidad y riesgo cardiometabó Revisión. CIMEL 16(2): 106-113.

- Qasim A, Turcotte M, de Souza RJ, Samaan M.C, Champredon D, et al. (2018) On the Origin of Obesity: Identifying the Biological, Environmental and Cultural Drivers of Genetic Risk Among Human Population. Obes Rev 19(2):121-149.

- Suverza A, Haua K (201) El ABCD de la evaluación del estado de nutrició México: Mc Graw Hill:pp 331.

- Ghaben AL, Scherer PE (2019) Adipogenesis and metabolic health. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20(4): 242-258.

- Samson S, Garber A (2014) Metabolic syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 43(1): 1-23.

- Magge SN, Goodman E, Armstrong SC (2017) The Metabolic Syndrome in Children and Adolescents: Shifting the Focus to Cardiometabolic Risk Factor Clustering. Pediatrics 140(2): e20171603.

- Tagi VM, Giannini C, Chiarelli F (2019) Insulin resistance in children. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 10: 342.

- Lentferink YE, Elst MAJ, Knibbe CAJ, and Marja MJvan (2017) Predictors of Insulin Resistance in Children versus Adolescents with Obesity. J Obes 2017: 3793868.

- Piña-Aguero MI, Zaldivar-Delgado A, Salas-Fernández A, Azucena Martínez-B, Mariela Bernabe-G, et al. (2018) Optimal Cut-off Points of Fasting and Post-Glucose Stimulus Surrogates of Insulin Resistance as Predictors of Metabolic Syndrome in Adolescents According to Several Definitions. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 10(2): 139-146.

- Cardenas-Vargas E, Nava JA, Garza-Veloz I, Mayra CTC, CarlosGT et al. (2018) The Influence of Obesity on Puberty and Insulin Resistance in Mexican Children. Int J Endocrinol 2018: 7067292.

- Tchernof A, Després JP (2013) Pathophysiology of human visceral obesity: an update. Physiol Rev 93(1): 359-404.

- Blackett PR, Wilson DP, McNeal CJ (2015) Secondary Hypertriglyceridemia in Children and Adolescents. J Clin Lipidol 9(5 Suppl): S29-40.

- Carlos LJ, Arthur LW, Ferraz Simões C, Gustavo Hde Ol , Karine O al. (2019) Triglyceride/glucose Index Is a Reliable Alternative Marker for Insulin Resistance in South American Overweight and Obese Children and Adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 32(10): 1163-1170.

- Gómez García A, Urbina Treviño MV, Villalpando Sánchez DC, Cleto AA (2019) Diagnostic Accuracy of Triglyceride/Glucose and triglyceride/HDL Index as Predictors for Insulin Resistance in Children with and Without Obesity. Diabetes Metab Syndr 13(4):2329-2334.

- Giannini C, Santoro N, Caprio S, Grace Kim, Derek L, et al. (2011) The Triglyceride-to-HDL Cholesterol Ratio: Association with insulin resistance in obese youth of different ethnic backgrounds. Diabetes Care 34(8): 1869-1874.

- Iwani NA, Jalaludin MY, Zin RM, Md Zain F, Janet Y H H, et al. (2017) Triglyceride to HDL-C Ratio is Associated with Insulin Resistance in Overweight and Obese Children. Sci Rep 7: pp40055.

- Nogueira TFD, Zambon MP (2013) Reasons for Non-Adherence to Obesity Treatment in Children and Adolescents. Rev Paul Pediatr 31(3): 338-343.

- Sun J, Wang Y, Zhang X, He, Hong AP (2019) The Effects of Metformin on Insulin Resistance in Overweight or Obese Children and Adolescents: A PRISMA-compliant Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 98(4): e14249.

- Lentferink YE, van der Aa MP, van Mill EGAH, Knibbe CAJ, van der Vorst MMJ, et al. (2018) Long-term Metformin Treatment in Adolescents with Obesity and Insulin Resistance, Results of an Open Label Extension Study. Nutr Diabetes 8(1): 47.

- Bassols J, Martínez-Calcerrada JM, Osiniri I, Ferran Díaz-R, Silvia Xargay-T, et al. (2019) Effects of Metformin Administration on Endocrine-Metabolic Parameters, Visceral Adiposity and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Children with Obesity and Risk Markers for Metabolic Syndrome: a Pilot Study. PLoS One 14(12): e0226303.

- Kumar S, Kelly A (2017) Review of Childhood Obesity: From Epidemiology, Etiology, and Comorbidities to Clinical Assessment and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 92(2): 251-265.

- Manna P, Jain SK (2015) Obesity, Oxidative Stress, Adipose Tissue Dysfunction, and the Associates Health Risks: Causes and Therapeutic Strategies. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 13(10): 423-444.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.