Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Evaluation of Indiana’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program: Physician’s Perceptions

*Corresponding author: Luba L Ivanov, Department of Nursing, Chamberlain University, USA.

Received: June 23, 2021; Published: July 02, 2021

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2021.13.001876

Abstract

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) [1] are state funded databases that collect data on prescription output of controlled substances. Currently, 49 states within the U.S. have active databases. These databases were implemented as a response to the opioid epidemic, which was caused by an overproduction of opioids. This surplus of addictive medication resulted in physicians prescribing large and often unnecessary amounts of the opioids to individuals who needed pain management [2]. In 1994, Indiana started a form of PDMP known as the Indiana Scheduled Prescription Electronic Collection and Tracking (INSPECT) [3]. At that time only Schedule II drugs were reported using the electronic system. In 2004 it was expanded to Schedule II to V drugs. Currently, Schedule II to V controlled substances along with pseudoephedrine drugs are reported. Included in the reporting is physicians dispensing more than a 72-hour supply out of their office.

In this pilot study, thirteen employed physicians within Indiana were surveyed concerning their views and recommendations regarding Indiana’s PDMP. It was found that most physicians were satisfied with the effectiveness and efficiency of the PDMP, concluding that the databases operate as intended. However, many disagree on whether there is still misuse in prescribing opioids A possible innovation to create a more responsive reaction from data collected from the PDMP was suggested based on the responses of the physicians.

The opioid epidemic has disrupted countless communities, families, and individuals across the country. Many individuals became addicted to opioid medications following a medical procedure [4]. Historically, when an individual’s prescription of opioids would run out, physicians would refill the prescription further exacerbating the patient’s dependency on the drug. Many individuals are eventually rejected a refill on their prescription and are left with crippling withdrawals. These withdrawals have resulted in healthy and accomplished individuals turning to other sources to satisfy their need for opioids. The result is a shortening of that individual’s life expectancy as they search for more potent opiates like heroine. (Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain-United States, 2016).

According to Wilson N, et al. [5] opioids are responsible for more overdose deaths than any other drug, Opioid pain relievers are prescribed in Indiana at a rate of 65.8 per 100 persons which is higher the national average of 51.4 per 100 persons in 2018 [6]. In Indiana, approximately 90% of individuals with addiction begin using illicit drugs and the number of opioid poisoning deaths increased by 500%. This dramatic increase in substance use and opioid-poisoning deaths has brought this crises to the level of a large-scale epidemic (Indiana Government, 2020). In Indiana, the deaths of opioids are significantly higher than that of accidents or violence. Many states have passed laws related to a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) to monitor physician’s prescriptions of opioids and patients use of them.

Keywords: Opioid epidemic, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMP), Indiana Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP)

Background

Since the late 1990s, hospitals have seen an exponential increase in opioid dependency and overdose every year [7]. However, those responsible for making opioids easily accessible have taken minimal responsibilities for their role in the epidemic. According to [8], it was not until November of 2020 that a federal court demanded an $8.3 Billion landmark settlement from Purdue Pharma Pharmaceutical Company, one of the biggest manufacturers of opioids. This company, acting alongside many others within the pharmaceutical industry, cut multiple corners around laws on manufacturing, advertising, and distribution of opioids [8]. This case portrays the government’s ongoing dedication and focus on addressing the destruction the opioid epidemic has caused.

Another primary focus of new government legislation concerning opioids is to create laws and regulations that will combat a contributing factor of the epidemic: doctor shopping by patients. Doctor shopping is defined by [2] as an individual seeking multiple interactions with a variety of doctors and clinics in hopes of achieving a prescription for a controlled substance. This is a common practice among opioid-addicted patients once they are cut off their initial prescription. It is not uncommon for individuals to break bones or cause self- harm to receive another prescription. One solution that states have implemented to combat prescription practices, has been incorporating a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP). The CDC (2021) defines PDMPs as “an electronic database that tracks controlled substance prescriptions in a state.” PDMPs provide health authorities with information about physician prescribing of opioids and patient behaviors. The purpose of the PDMP is to have a system that stores and tracks data on opioid output and prescriptions.

Physicians in a state with PDMPs must report each prescription they write to their state’s PDMP. The PDMP stores this information in attempts to identify possible poor prescription practices among physicians prescribing opioids and to decrease the incidence of “doctor shopping” among patients. However, physicians must check the PDMP before prescribing opioids to ensure that there is not abuse of opioids by patients. Opioid pain relievers are prescribed in Indiana at a rate of 65.8 per 100 persons which is higher the national average of 51.4 per 100 persons in 2018 [6]. In Indiana, approximately 90% of individuals with addiction begin using illicit drugs and the number of opioid poisoning deaths increased by 500%. This dramatic increase in substance use and opioidpoisoning deaths has brought this epidemic to the level of a largescale epidemic [9]. In Indiana, the deaths of opioids are significantly higher than that of accidents or violence.

Evaluating The Impact of PDMPs

Several studies have been conducted to evaluate the impact of implementing PMDPs in a region [10] evaluated the impact that implementing a PDMP had on the opioid output of a given state. They converted the data collected from PDMPs in each state into a base unit of measurement: Morphine-Milligram Equivalent (MME). This universal unit of measurement allowed the researchers to identify changes in prescription trends across all brands and doses of opioid medications. They found that “From 1999 to 2008, the annual MMEs dispensed per capita increased fivefold. The data collected from [10] study provided the bases for a study conducted by the [11].

The Pew Charitable Trusts examined peer-reviewed literature on PDMPs and evaluated the effectiveness of the wide variety of programs/databases implemented across the United States. Differing from [10] research, the study conducted by the [11] was focused on evaluating the effectiveness of PDMPs based on responses from staff who monitor the databases. They analyzed, the effectiveness of different PDMP programs, and how they assess and address opioid output statistics. Both the [10,11] studies aimed at evaluating how effective PDMPs are, what makes them effective, and what can be done to increase their effectiveness at combating high and unregulated opioid output. While these studies used different techniques, both concluded that PDMPs had little impact on opioid output, because the database does not restrict how much a physician can prescribe, but merely tracks the data.

The Cost of the Opioid Epidemic

The implementation of PDMPs seems promising for the battle against opioid addiction and doctor shopping, but these programs do require a considerable amount of time, effort, and money to run effectively. The National Institute on [6] describes the extent of the growing economic burden of the opioid crises by sharing that “The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the total “economic burden” of prescription opioid misuse alone in the United States is $78.5 billion a year, including the costs of healthcare, lost productivity, addiction treatment, and criminal justice involvement.” With this information, it is undeniable that the costs of PDMPs, along with other programs and initiatives aimed at combating opioid addiction, are necessary investments that will contribute to lowering the economic burden of the opioid epidemic.

According to [12] the onset of the COVID-19 global pandemic in 2020 has only accelerated the growing deficit caused by the opioid epidemic, especially among native populations. [13] adds to this discussion of economic burden by focusing on Big Pharma’s responsibility for the opioid crisis. Specifically, [13] focuses on why the costs of the epidemic soared in proportion to the growth of Big Pharma’s profit. [13] claims that this disconnect is caused by one unique characteristic to the United States’ government, which is the lobbyist. The significance of this characteristic is that pharmaceutical lobbyists have a great influence on Congress when negotiating drug prices. [13] claims that Big Pharma has been able to avoid responsibility for the opioid epidemic, while driving up prices for maximum revenue. Regardless of intentions, the result of loose regulations on the pharmaceutical market, paired with lobbyists in all levels of legislation have influenced the cost of opioids and its resultant devastating effect on the public.

Causes of the Opioid Epidemic

Mann B, et al. [8] stated that both the media and all levels of government have slowly become aware of the outcomes of the opioid epidemic. This has been seen in the prosecution of Purdue Pharma among other pharmaceutical companies in the industry [7]. Meldrum (2020) also blames slow developments in the standardization of how medical professionals address, treat, and manage pain in patients. [14] refers to the government’s legal recognition that the pharmaceutical industry intentionally downplayed the risk of addiction posed by OxyContin and misled both physicians and the healthcare industry by overstating the benefits of opioids for chronic pain. The worst part, according to [14] is that it took until 2007, when Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to misbranding oxycontin that actions for the medical field and pharmaceutical research industry to acknowledge the downside and widespread destruction caused by poor prescribing patterns. In 2020, Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to fraud and kickback conspiracies [15,16].

Effect of Opioid Epidemic on States

While the opioid epidemic has cost the United States hundreds of millions of dollars, the damages have not impacted regions of the U.S. equally. Studies conducted by [17] have shown that the opioid epidemic has largely impacted poor rural and dense urban regions significantly more than wealthier suburban communities. In addition to this, states such as West Virginia and Ohio have experienced the highest amounts of economic burden because of widespread opioid addiction and overdoses. The opioid pain relievers prescribing rate in Indiana is 74.2 per 100 persons higher than the national average of 58.7 per 100 persons in 2017 [6]. More than 70, 200 Hoosiers died from drug overdoses in 2017 at a rate of 21.7 per 100,000 persons [6] According to Rhoades et al, the predominant reasoning behind the implementation of Indiana’s PDMP is to monitor physicians who prescribe opioids to ensure that they are not taking advantage of their patients by prescribing them excess amounts of addictive medications (2019).

Overall, the opioid epidemic is a complex issue. As a result of a multitude of factors and causes, the epidemic requires a variety of solutions and interventions to reverse the damages. It is important that those who have been harmed by the opioid epidemic are provided relief, and those responsible are held accountable. In addition, the methods used by the pharmaceutical industries to over produce opioids at such a large scale have been widely addressed and made impossible to repeat; however, lobbyists still have a large influence on the actions of Congress and other local and state governments. Further developments are needed with PDMPs and other government-backed forms of regulation. The purpose of this pilot study was to better understand physician’s opinions about Indiana’s PDMP. The information will help legislators know where changes in the PDMP are needed. The research question in this study is: To what extent do the physicians in Indiana believe that their PDMP is working well? A survey was used to collect data on physician’s opinions.

Methodology

An exploratory research design was used to answer the research question: To what extent do the physicians in Indiana believe that their PDMP is working well? A survey with 15 Likert questions and two open ended questions was used to explore Indiana’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP).

Selection of Participants

Snowball sampling was used to select participants for this study. Physicians within Indiana who are actively permitted to prescribe opioids were recruited by the researcher first by reaching out to a physician known to the family. This physician then recommended others that might be interested in participating in this study. The researcher reached out to them regarding their participation by phone and email. Physicians received the surveys by email and returned them by email. The goal was to have 30 participants. However, due to Covid-19, only 13 participants were recruited.

Ethical Considerations

The survey was developed by the researcher. Survey questions were reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB), at Carmel High School, in Carmel Indiana. The survey was reviewed for possible ethical violations prior to survey administration. Each participant received a consent form that included the nature of the study, the intention of the study, and the physician’s role in the study. Participants were informed that they have the right to leave any question they choose blank. It was decided in the development of the survey that asking physicians questions about their personal interactions with patients, prescription patterns/habits, or other questions would conflict with HIPAA regulations. Steps were taken to ensure that the participants were kept anonymous as no names were on the surveys. Their names were never recorded or used in the analysis. The questions in the survey sought to obtain physicians’ opinions about the Indiana Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP).

Procedure

The participants were selected by personal contact with the first physician who is known to the family. All data was collected by email through the internet, and the surveys were administered through google forms. Participants were contacted by email. They were first sent a letter of request. If a participant accepted the letter of request, the survey was sent to them via google forms. Google forms automatically tracked and statistically analyzed responses to the survey without recording any names of submission. The graphs made by google forms organized the responses based on each question response. Once all the data was collected, the organized responses could be analyzed and reviewed to determine frequencies on each survey question.

Results

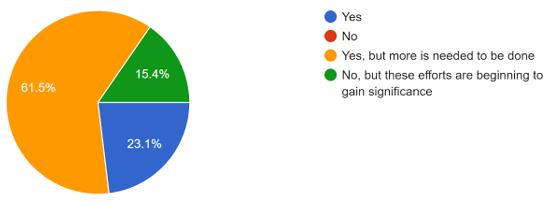

In response to the first survey question 61.5% of respondents indicated that the nation-wide efforts to combat the opioid epidemic have created significant improvements in public health but more are needed (Figure 1). The next survey question asked participants “What do you believe is the most needed change with regards to the current methods of prescribing opioids?”. Thirty eight percent agreed that alternative medications to opioids are needed for addressing pain. Several of these participants also noted that further research is needed, as there are no medications currently being tested that are as effective as opioids at relieving pain. Other participants responded that patients should be offered rehabilitation and psychiatric help following the expiration of their prescription if they have become addicted to the opioids. Some participants suggested that patients should be able to receive medical treatment such as methadone therapy when withdrawing from opioids. Thirty eight percent of participants expressed that opioids are too heavily emphasized as chronic pain medications within the medical community.

When the participants were asked what they believed was the most impactful and recent form of legislation regarding opioid prescribing, there were three general responses. Fifty three percent of the participants cited Indiana’s PDMP, or drug monitoring database, as the most impactful form of legislation in recent years. Twenty percent of participants, referred to a law passed in 2019 by Indiana State Senator Jean Leising, which required drug manufacturers and distributors to label opioid medications as an opioid on the packaging. The law also required that the labels on prescription bottles/packages warn patients of the risk for addiction associated with opioids (Ross 2019). Another participant cited a form of legislation that recognized opioid addiction as a medical condition, therefore ensuring that addiction treatment would be covered by insurance. A final unique response from 1 participant focused on EKRA (Eliminating Kickbacks in Recovery Act), which criminalized patient brokering. Patient brokering describes a physician who refers a patient to an addiction rehabilitation facility in return for some sort of compensation or kick back [18].

The next survey question asked participants if they believed any future changes or improvements were needed with Indiana’s PDMP. Ninety two percent of participants responded that the database fulfills its intended purpose. In terms of the ability of the PDMP to monitor prescription output, nearly 100% of participants agreed that the PDMP effectively fulfills this purpose. However, when asked to rate Indiana’s response to the opioid epidemic on a scale of 1 to 10, 53.9% of respondents rated Indiana’s response from 3 to 5 (Figure 2). As noted in the data, many participants view their state’s response to the opioid crisis as average. It can be gathered from these responses that there is still much work that needs to be done to reverse the effects of opioid prescribing practices in Indiana (Figure 3).

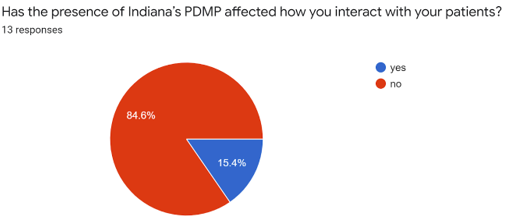

Fifteen percent of participants responded that Indiana’s PDMP did impact how they interacted with their patients; but they considered the effects of the program as beneficial to their relationship with patients. The overwhelming majority of participants response to this question agrees with the findings of [19], in that the implementation of a PDMP database does not impact how they relate to their patients. Eighty five percent of participants agreed that the overall health of their patient is more important than addressing largely their pain. This reflects the fact that nearly all physicians recognize opioid addiction as a health condition, and although it is an important medical issue, a patient’s overall health is most important to them.

Participants were asked whether they believe that decriminalizing opioids, like what was done in Oregon in their most recent election, would improve addiction and overdose rates. The responses to this question were overwhelmingly in the negative. With an addictive substance such as opioids, the participants all agreed that the only thing that would result from decriminalization would be higher rates of addiction and overdose. Essentially, the participants concluded that there is no place for this medication to be used without a specific and limited medical purpose (Figure 3).

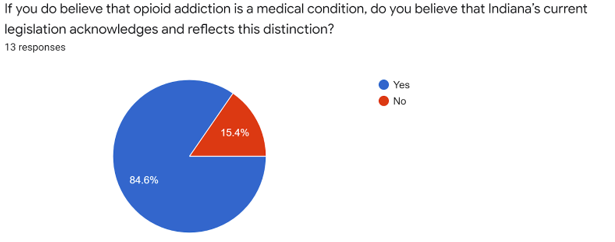

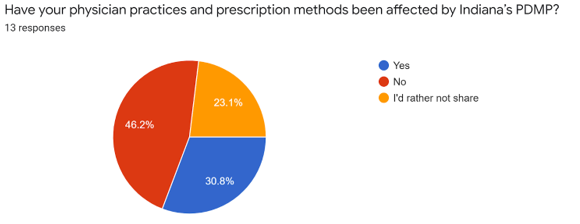

Eighty four percent of participants agree that the state of Indiana, and its legislation properly identifies, defines, and focuses on opioid addiction as a medical condition. Participants were asked if there were any current alternatives to opioids that they believed were just as effective. The responses were universally in agreement that while there are some naturally occurring painkillers that may be less addictive than opioids, they typically are not nearly as specific in functionality and as effective as opioids. They also responded that there is not enough proper research and testing done on alternatives to opioids. One participant referred to medical marijuana for treating chronic pain, as the substance is much less addictive than opioids. The same participant also acknowledged that the use of medical marijuana is not extensively researched for pain, and there is disagreement as to its effectiveness and possible side effects. The overall conclusion was that opioids are very effective at relieving pain at a neurological level, but there needs to be much more research before another medication is found that can replace opioids (Figure 4). Only 31% of respondents felt that their practice and prescription methods were affected by Indiana’s PDMP. It was not clear as to why there was a low response to how physician’s prescribe opioids is affected by Indiana’s PDMP (Figure 5).

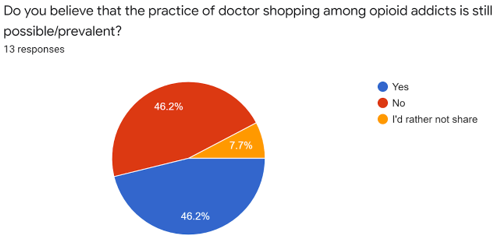

The participants were split on their response as to whether patients doctor shop to obtain opioids. This data was surprising upon analysis, because while a large percentage of participants believed that the state’s PDMP was effective and needed no improvements, the participants disagreed on whether doctor shopping is still viable. If the PDMP was effective and did its job properly, it would be logical to assume that the prevalence of doctor shopping would be low, as that is the fundamental purpose of the state’s PDMP. This could mean that the participants believed that the PDMP does its job effectively, yet they knew of loopholes or instances where other physicians have gotten away with mass prescribing opioids. The inconsistency in this data is something that would need further research across a much larger participant population.

Discussion

The findings of this study have given a new perspective as to how physicians are involved with Indiana’s PDMP. This study found that most physicians would like to see new alternative medications begin to be developed and researched to replace opioids. In addition, this study found that while many physicians believe that Indiana’s PMDP is effective at its purpose of tracking opioid prescriptions, many disagree on whether there is still misuse in prescribing opioids. This could mean that while the state’s PDMP does a proper job at identifying those that are not prescribing according to the laws, the law enforcement to which it reports data may not properly enforce infractions in the database. This may be due to the current legislation (Indiana PDMP) or a failure of the authorities to enforce violation of the legislation.

It would be productive and beneficial to create a secondary program for recording opioid prescriptions that focuses more on those who prescribe opioids improperly better linked with authorities that can take proper action, this could help future physicians be less inclined to prescribe patients opioids unless the patient meets the requirement for prescribing. Perhaps the most important finding of this study was that nearly all physicians believe that more work is needed to be done by lawmakers and researchers alike to ensure that the damage of the opioid crisis is reversed. If a less addictive, yet comparatively effective pain medication is developed, and prescription patterns are further controlled and monitored with greater scrutiny, it could be ensured that the same causes of the epidemic may never be repeated.

Limitations of Study and Future Research

Limitations of this study include a small sample size and nonrandomization of participants. In addition, the findings cannot be generalized to other states. However, even with these limitations, the findings from this study support the need for more research done not only in Indiana but other states as to how effective their PDMPs are and whether changes in them need to be made to make them more efficient at decreasing the opioid and other drug related addictions, along with decreasing inconsistencies in how physicians prescribe opioids.

References

- Centers for Disease Control (2021) Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs).

- Peirce G, Smith M, Abate M, Halverson J (2012) Doctor and Pharmacy Shopping for Controlled Substances. Medical Care 50(6): 494-500.

- Keith DA, Shannon TA, Kulich (2018) The prescription monitoring program data: What it can tell you. The Journal of the American Dental Association (JADA) 149(4).

- Felter C (2020) The US Opioid epidemic. Council on Foreign Relations

- Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H, Davis NL, et al. (2020) Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths -United States, 2017-2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 69(11).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH) (2020) Indiana Opioid-Involved Deaths and Related Harms.

- Meldrum, Marcia L (2016) The Ongoing Opioid Prescription Epidemic: Historical Context. American Journal of Public Health 106(8): 1365-1366.

- Mann B (2020) Federal Judge Approves Landmark $8.3 Billion Purdue Pharma Opioid Settlement.

- Indiana Government (2020) Indiana Drug Overdose Dashboard.

- Brady J, Wunsch H, Di Maggio C, Lang B, Giglio J, et al. (2014) Prescription Drug Monitoring and Dispensing of Prescription Opioids. Public Health Reports 129(2): 139-147.

- Pew Charitable Trusts (2016) Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs.

- Indian Health Services (2021) Opioids and the Covid-19 pandemic: Addressing the opioid crises during the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Deangelis C (2016) Big Pharma Profits and the Public Loses. The Milbank Quarterly 94(1): 30-33.

- Jones MR, Viswanath O, Peck J, Kaye AD, Gill JS, et al. (2018) A Brief History of the Opioid Epidemic and Strategies for Pain Medicine. Pain Medicine Pain Ther 7(1): 13-21.

- The United States Department of Justice (2020) Opioid Manufacturer Purdue Pharma Pleads Guilty to Fraud and Kickback Conspiracies.

- Carise D (2018) What we can do to stop patient brokering: Meaningful change can be accomplished through legislation, increased public awareness and at the treatment level. Behavioral Healthcare Executive 38(4): 15.

- Brill A, Ganz S (2018) The geographic variation in the cost of the opioid crisis. American Enterprise Institute.

- Keogh JG, Fink JL (2020) Recent law addresses the opioid crisis. Pharmacy Times 88(8).

- Rhodes E, Wilson M, Robinson A, Hayden J, Asbridge M, et al. (2019) The effectiveness of prescription drug monitoring programs at reducing opioid-related harms and consequences: A systematic review Bio Medical Central (BMC) Health Service Research 19(784).

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.