Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Understanding College Students Perceptions of “What is Sex”?

*Corresponding author: Martin C. Mahoney, Department of Internal Medicine, RPCI, 665 Elm Street, Buffalo, NY 14263, USA, Email: martin.mahoney@roswellpark.org

Received: May 07, 2021; Published: May 24, 2021

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2021.13.001822

Abstract

Background: While there is strong consensus that vaginal and anal intercourse both constitute “having sex”, there is far less agreement about other sexual behaviors which also increased risk. The purpose of this report is to examine responses regarding which sexual interactions are classified as “having sex” by university students.

Methods: We completed a cross-sectional survey of 1991 college students at 2 universities using a self-administered questionnaire during 2010 and 2011. The main dependent variable examined dichotomous responses to a series of 11 items regarding whether respondents considered various sexual behaviors as “sex.”

Results: Penile-vaginal intercourse and penile-anal intercourse was endorsed as “sex” by 94% and 76% of respondents, respectively. Receiving oral-genital contact from a partner and providing oral-genital contact to another person were both classified as “sex” by about 45% of college students. Less than 25% of respondents reported that other behaviors including touching/fondling genitals, deep kissing, oral contact with breasts, or touching breasts represented “sex”.

Conclusions: Given the ambiguous definitions of what constitutes “sex” among young adults, these findings underscore the need to use explicit behavior-specific terminology in sexual health promotion, research, educational and clinical settings to clearly communicate risk.

Keywords: Sexual Behavior; Terminology; Risk; Sexual Definitions; Cross-Sectional Studies

Introduction

Although there is ongoing research investigating sexual behaviors in adolescents and young adults, there is substantial ambiguity surrounding how people in this age group define specific sexual behaviors. While the term “sexual intercourse” most commonly denotes penile-vaginal penetration, a variety of views exist concerning what constitutes “having sex.” The term “sex” can also be used to describe various forms of sexual intercourse such as the act of vaginal, anal, or manual (using hands), or oral-genital stimulation, with a partner [1]. Still, many researchers maintain that “sex” is difficult to define and can differ across gender, age, and scenario [2-8]. Sex can be regarded as a risky behavior as it may lead to unplanned pregnancies and Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), including Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). In 2015-2017, 40% of adolescents aged 15-19 reported ever having had penile-vaginal intercourse and 45% reported having oral sex.

Moreover, the proportion of young people who have had sexual intercourse increases rapidly as they age through adolescence; 95% of 25-year-olds reported having had sexual intercourse [9]. A greater understanding of these definitions is needed to better estimate disease risk associated with these behaviors and as well as to inform public health interventions to mitigate these risks.

Several studies have examined how university students in the United States perceive various forms of sexual contact. A 1999 publication of data collected in 1991 reported that only 40% of 599 college students identified either receiving or providing oral sex as “having sex” compared with 81% who endorsed penile-anal intercourse and 99% who endorsed penile-vaginal intercourse as “having sex” [7]. Data collected from university students in 1999, 2001, 2007 and 2010 reported similar findings [10-12]. A more recent study published in 2015 based upon data from 594 undergraduate students found that nearly one-half of students expressed uncertainty about whether oral sex constituted “having sex”; where approximately 25% selected “probably not sex” and 23% selected “probably sex.” In addition, certainty that a behavior counted as “having sex” differed when rating their own behaviors compared to rating a partner’s behaviors [8]. While there is strong consensus, although not unanimity, that vaginal intercourse constitutes “having sex”, there is far less agreement about other sexual behaviors. These inconsistent definitions of sex may lead adolescents and young adults to underestimate the health risks and implications associated with various types of sexual activity, particularly anal and oral sex. The purpose of this report is to examine responses regarding which sexual interactions are classified as “having sex” by university students.

Methods and Materials

Design

This cross-sectional study involved completion of a selfadministered questionnaire by college students at two different universities. This research protocol was approved by the Social and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board (SBSIRB) at the University at Buffalo (Study # 3065: Adoption of the HPV vaccine: A pilot study of knowledge and attitudes in western New York) and all participants provided assent.

Study Population

Male and female students were recruited from two universities during two academic years (2010 and 2011) using an approach as previously described [13]. Students were recruited using a convenience sample using similar approaches. At university A, eligible students were enrolled from various health courses and received extra credit, while at university B students were enrolled in general psychology classes and were offered research credit toward the fulfillment of their course requirements in exchange for their participation. These courses were targeted based upon their inclusion of students from across varied academic majors and class levels. Respondents completed an Internet-based survey outside of class time. The analytic file was restricted to persons who selfidentified as ages 18-26 years since these ages were considered to reflect a typical college age population.

Survey Instrument

Data presented in this paper focuses on a module of a larger main survey, which contained sections on respondent demographics, sexual and health behaviors, knowledge, and awareness about Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), and HPV vaccination. Respondents at both universities completed the same survey. The core survey items remained unchanged between 2010 and 2011, however selected modules were varied.

Outcome Measure

The main dependent variable examined dichotomous responses to a series of 11 items regarding whether respondents considered various sexual behaviors as “sex” [7,14]. Respondents were asked “Would you say you ‘had sex’ with someone if the most intimate behavior you engaged in was... (mark yes or no for each behavior).” Each of the items was phrased in a manner which was neutral about gender or sexual orientation (Table 1-5).

Covariates

We explored the impact of various independent variables including gender (male, female), age (18-19, 20-26 years), school (university A, university B), race (White, African American, Asian, other), ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic), and country of origin (US born, foreign born).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were used to explore associations between the dependent and independent variables. All significance testing was assessed using a p-value of <0.05. Analyses were completed using SPSS version 21.0.

Results

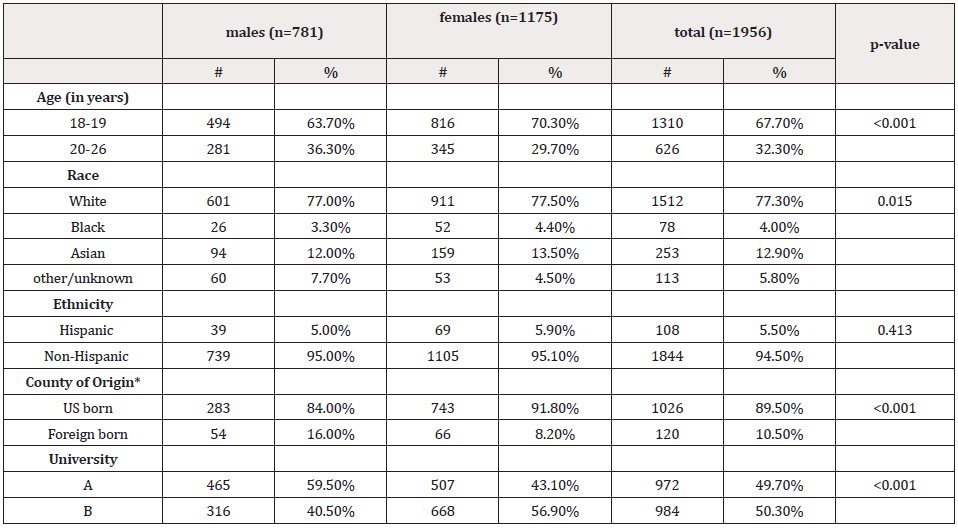

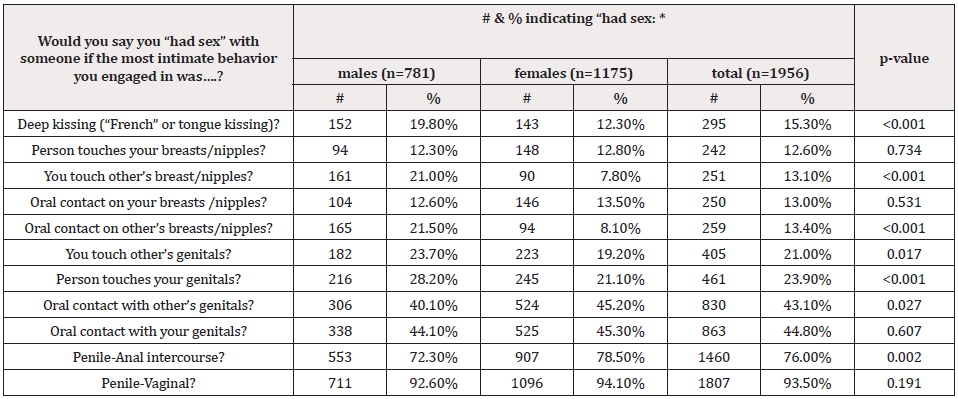

The final analytic file contained 1991 students ages 18-26 years, with 815 respondents during calendar year 2010 and 1176 from 2011. As shown in Table 1, respondents were 59% female, 67% were ages 18-19 years, 77% white, 94% non-Hispanic and 89% reported being born in the US. Nearly all respondents reported having sex with opposite gender partners (e.g., heterosexual). Table 2 summarizes responses addressing whether respondents would say that they “had sex” based on a series of statements describing various intimate behaviors. Overall, 94% of respondents agreed that penile-vaginal intercourse represented “sex.” Penileanal intercourse was endorsed as “sex” by 76%. Receiving oralgenital contact from a partner and providing oral-genital contact to another person were both classified as “sex” by about 45% of college students. Between 20% and 25% of respondents reported that another person touching/fondling their genitals or touching/ fondling someone else’s genitals represented “sex”. Between 12% and 15% of respondents stated that they “had sex” with deep kissing, oral contact with another person’s breasts, someone else having contact with their breasts, another person touching/fondling their genitals or touching/fondling someone else’s genitals. Significantly more males than females classified touching/fondling another person’s breasts, someone touching/fondling their genitals, or deep kissing as “having sex”. Females more commonly reported oral-genital contact and penile-anal intercourse as “having sex.”

Table 1: Selected demographics of college student respondents, by gender, 2010 & 2011.

Subcategories may not sum to column totals due to missing data.

*Data for 2011 only.

Table 2: Responses among college students to survey items regarding “What is Sex?” by gender.

*Number and percentage of respondents who agreed with each statement.

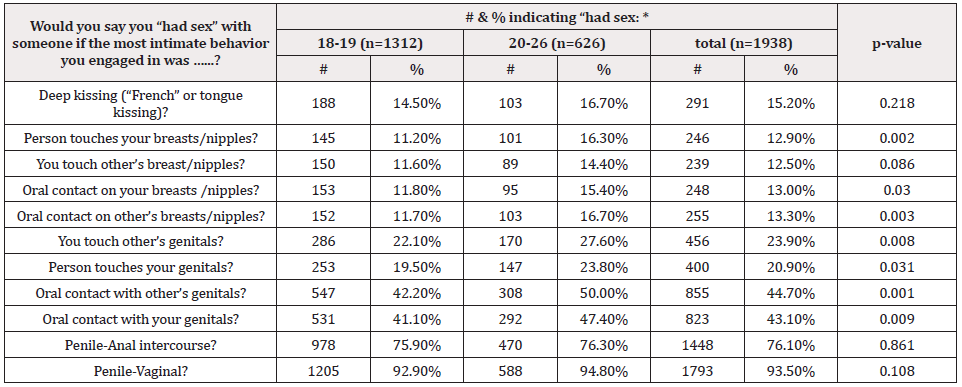

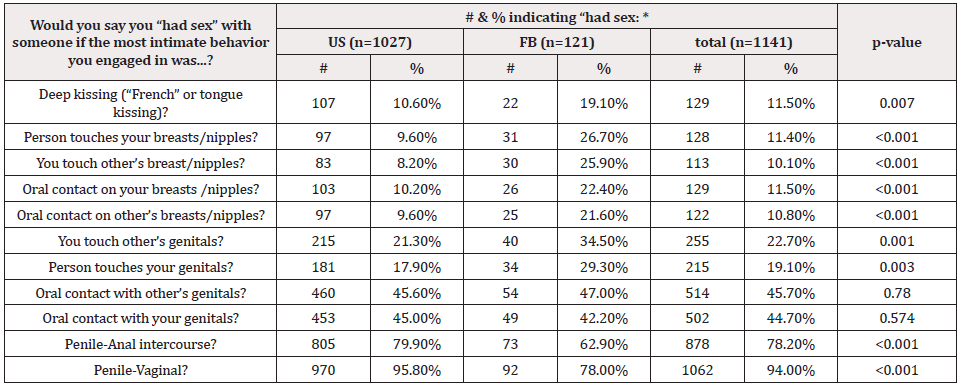

As shown in Table 3, there were no differences by age group in the proportion of persons identifying penile intercourse and anal intercourse as “sex”; however, a slightly larger proportion of persons in the 20-26-year-old group compared to persons ages 18- 19 years consistently endorsed oral and/or manual contact with breasts and genitals as “sex”. Table 4 presents responses stratified by country of origin. Respondents who self-identified as foreign born were more likely than US-born respondents to identify oral or manual breast contact, manual genital contact and deep kissing with another person as “sex”, while a larger proportion of USborn respondents identified penile-vaginal intercourse and anal intercourse as “sex”.

Discussion

The importance of standardized terminology in sexual and reproductive health cannot be underestimated since understanding how individuals define “sex”, abstinence, safe sex, and other concepts has significant implications for sexual health [15]. With regard to sexual violence, persons engaging in sexual behaviors need to provide clear and affirmative consent, which requires a shared understanding of terms like “sex” and/or using more explicit language to reference sexual behaviors. In addition, the federal definition of rape includes all penetrative sexual behaviors, including oral penetration. Ambiguities regarding specific sexual behaviors not only pose challenges for physicians and health educators, but also for researchers and policy makers who rely upon self-reported data on the frequency and prevalence of sexual behaviors, which rests, in part, on a common understanding of the questions being asked and the terms being used. However, having ambiguous definitions of the term “sex” is not unique to young adults in America, as a series of studies conducted in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom have also demonstrated considerable variability in how university students define “having sex” [16-19].

Our findings did reveal some differences by gender regarding which interactions were viewed as “having sex”. Although these differences were statistically significant, they were relatively modest quantitatively. Findings in this report and in similar studies among college populations in the United States, tend to diminish the significance and hazards of oral sex. Adolescents tend to view oral sex as less risky and characterize this behavior as “casual” and “non-intimate” [20]. Oral sex is effective in transmitting various viral and bacterial pathogens [21].

The college environment appears to exert a strong influence on sexual attitudes and behaviors [15,21-23] which may explain in part the somewhat higher proportion of persons ages 20-26 years who endorse interactions involving oral and/or manual contact with breasts and genitals as “having sex”. It is also possible that these older students have simply had more time to engage in sexual behaviors and/or may have resolved earlier conflicts over personal and religious values which might have resulted in inconsistencies in their personal definitions of whether they had engaged in sexual activities.

Interpretation of responses to “what is sex?” among foreignborn persons is more difficult to understand as this group of respondents included various groups of persons of Asian ancestry (India, Chinese, Korean, Japanese, etcetera) and overall is quite heterogeneous. Foreign students studying in the U.S. bring different cultural values regarding sex and gender interactions. As a group, they more frequently classified non-penetrative breast and genital contact as “having sex” while less frequently labeled penile-anal and penile-vaginal intercourse as “having sex”. It is also possible that this group might have had comprehension problems with these items, even with the explicit definitions provided. Foreign born studies are unlikely to have had formal sex education sessions as are routinely provided in the United States and may be less familiar with terms like “genitals,” “vagina,” “oral contact,” or even “intercourse.” Another possibility is that, notwithstanding the issue of heterogeneity, this group overall likely holds more conservative sexual values than American students.

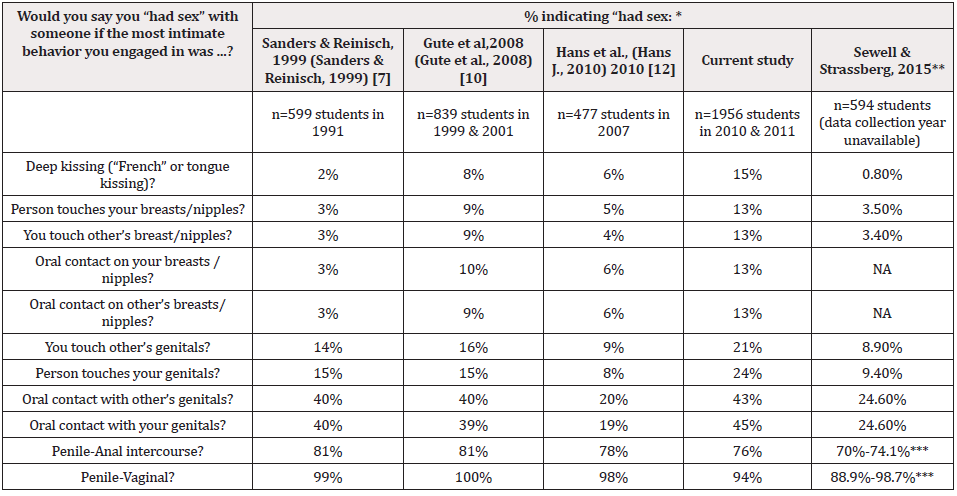

Table 5 compares results from selected surveys of American college students based on identical survey items. Overall, there appears to be limited changes over time and continued ambiguity regarding which personal interactions are perceived as “having sex” among college students. Among the behaviors assessed there was a relatively strong consensus about the concept of “penetration”; with penile-vaginal intercourse being almost universally included as “sex” and penile-anal intercourse generally included as “sex”. A more recent paper by Sewell, Strassburg [8] suggested the definitions of sex are influenced by several contextual factors including whether the behavior being assessed is that of the respondent or their significant other, the order in which questions are asked relating to behaviors by the respondent and their significant other and the presence or absence of an orgasm [8].

Table 5: Comparisons across selected studies, responses among college students to survey items regarding “What is Sex”?

a) Percentage of respondents who agreed with each statement.

b) Participants selected “Definitely Sex” on a four-point Likert-type scale.

c) Range dependent on whether orgasm occurred.

Consistent with previous studies, we found that less than onehalf of respondents defined receiving or providing oral-genital contact as “sex”, which may reflect Sanders and Reinisch’s notion of “technical virginity” in which sexual contact which does not culminate in penetrative intercourse is not considered to be “sex” [7]. This is best recognized during the 1998 debate regarding whether former President Bill Clinton engaged in “sex” with Ms. Monica Lewinsky during several alleged encounters between 1995 and 1997. These attitudes may also be reflective of societal and media representations minimizing the consequences of oral sex combined with a traditional cultural emphasis on penetration as a defining feature of sex. In addition, school-based sex education programs and popular media may have contributed to the “normalization” of oral-genital contact [24]. However, this finding is especially concerning given the risk of transmitting STIs through oral-genital contact (Prevention, 2013) [25] as well as through other intimate behaviors associated with “hooking up” and “friends with benefits” relationships, all of which involve varying degrees of skin-to-skin contact facilitating spread of potential infections.

Strengths of our current study include the use of survey items which are identical to those used in similar studies, data collection over two time periods at two large state universities, a sizable study population, and a focus on a typical college age range of 18-26-year-olds. These findings are most generalizable to similar college student populations. One potential limitation of our study is the reliance upon a convenience sample of mostly whites and selfidentified heterosexual respondents. Defining sex as solely vaginal/ anal intercourse may exclude women in same-sex relationships from having sex at all and seems to inadvertently premise sex on male participation. Accordingly, it might be necessary to modify survey items on how “sex” is defined to be more reflective of the sexual diversity of college students and to acknowledge the importance of using more inclusive language in healthcare setting and health education/promotion activities. In addition, progress has been made since 2011 with respect to accessing available resources and improving LGBTQ+ sexual health among college students. Other limitations include the lack of contextualization of items in terms of interpersonal behaviors within or outside of established relationships, potential differences in responses by culmination of orgasm and the lack of psychosocial measures. We were unable to assess for racial/ethnic differences in response beyond an assessment of “foreign born”.

Conclusions

Research which asks questions about sexual practices can be accurate and reliable only if there are clear definitions of different sexual activities. These findings underscore the need to use behavior-specific terminology in clinical settings, sexual health promotion, sex/behavioral research, and sexual education, given the potentially ambiguous definitions of what constitutes “sex” among young adults.

Sexual health education campaigns must consider the range of popular expressions that can be used to express a single concept, while simultaneously keeping in mind the variability in meaning that may be attached to a single term. Clinicians need to be similarly attuned to the range of expressions that patients may use to describe their sexual behaviors and reproductive health to accurately assess risk and to provide appropriate patient care and disease prevention strategies.

Our findings contain a constructive message for sexual health interventions. If definitions of “what is sex?” are malleable, then the potential exists to develop more explicit definitions which could result in improved sexual health awareness and enhanced recognition of modifiable risky behaviors. Healthcare providers and public health professionals need to acknowledge this ambiguity regarding how young adult populations define “sex” to ensure that services and preventive interventions are consistent with a clearly communicated definition of “what is sex”?

Key Messages

a) There is a strong consensus among heterosexual college

students that penile-vaginal and penile-anal intercourse

constitute “having sex.”

b) There is ambiguity among heterosexual college students

surrounding whether oral-genital contact and non-penetrative

breast and genital contact represent engaging in “sex”.

c) While responses were statistically different by gender and

by age group, the magnitude of these difference was generally

modest.

d) Respondents who self-identified as foreign born were

more likely than US-born respondents to identify nonpenetrative

breast and genital contact as “sex”.

e) These findings underscore the need to use explicit

behavior-specific terminology in sexual health promotion,

sexual violence prevention, behavioral research, and

educational settings.

Funding

This research was funded in part by Roswell Park Cancer Institute, a National Cancer Institute (NCI) Diversity Supplement 3U54CA153598-02S1 and the Western New York Cancer Coalition (WNYC2) Center to Reduce Disparities, National Institutes of Health (NIH)/NCI/Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (CRCHD) U54 CA153598-01.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Planned Parenthood. Glossary A-Z. Learn.

- Edwards W, Coleman E (2004) Defining sexual health: a descriptive overview. Archives of Sexual Behavior 33: 189-195.

- Lorber J (1996) Beyond the binaries: depolarizing the categories of sex, sexuality, and gender. Sociological Inquiry 66(2): 143-159.

- McBride KR, Sanders SA, Hill BJ, Reinisch JM (2017) Heterosexual Women’s and Men’s Labeling of Anal Behaviors as Having “Had Sex”. The Journal of Sex Research 54(9): 1166-1170.

- Mehta C, Sunner L, Head S, Crosby R, Shrier L (2011) “Sex isn’t something you do with someone you don’t care about”: young women’s definitions of sex. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology 24(5): 266-271.

- Peterson Z, Muehlenhard C (2007) What is sex and why does it matter? A motivational approach to exploring individuals' definitions of sex. Jouranl of Sex Research 44(3): 256-268.

- Sanders S, Reinisch J (1999) Would you say you "had sex" if...? JAMA 281(3): 275-277.

- Sewell KK, Strassberg DS (2015) How do heterosexual undergraduate students define having sex? A new approach to an old question. Journal of sex research 52(5): 507-516.

- Institute G (2019) Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in the United States.

- Gute G, Eshbaugh EM, Wiersma J (2008) Sex for you, but not for me: discontinuity in undergraduate emerging adults' definitions of "having sex". J Sex Res 45(4): 329-337.

- Sanders SHB, Yarber Y, Graham C, Crosby R, Milhausen R (2010) Misclassification bias: diversity in conceptualizations about having "had sex" Sexual Health 7(1): 31-34.

- Hans JD, Gillen M, Akande K (2010) Sex redefined: the reclassification of oral-genital contact. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 2(42): 74-78.

- Licht AS, Murphy MJ, Hyland AJ, Fix BV, Hawk LW, et al. (2010) Is use of the HPV vaccine among female college students related to HPV knowledge and risk percpetion? Sexually Transmitted Infectious Diseases 86(1): 74-78.

- Sandberg Thomas S, Kamp Dush C (2013) Casual sexual relationships and mental health in adolescence and emerging adulthood. The Journal of Sex Research 51(2): 121-130.

- Byers ES, Henderson J, Hobson K (2009) University Students' Definitions of Sexual Abstinence and Having Sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior (38): 665-674.

- Lefkowitz E (2005) "Things have gotten better": Developmental changes among emerging adults after the transition to university. Journal of Adolescent Research 20: 40-63.

- Pitts M, Rahman Q (2001) Which behaviors constitute "having sex" among university students in the UK? Archives of Sexual Behavior (30): 169-176.

- Randall H, Sandra BE (2003) What is sex? Students' definitions of having sex, sexual partner, and unfaithful sexual behavior. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 12(2): 87-96.

- Richters, J, Song A (1999) Australian university students agree with Clinton's definition of sex. BMJ 318(7189): 1011-1012.

- Vannier S, Byers ES (2013) A qualitative study of university students' perceptions of oral sex, intercourse, and intimacy. Arch Sex Behav 42(8): 1573-1581.

- Saini R, Saini S, Sharma S (2010) Oral sex, oral health and orogenital infections. J Glob Infect Dis 2(1): 57-62.

- Lefkowitz E, Boone T, Shearer CL (2004) Communication with best friends about sex-related topics during emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 12: 217-242.

- Lefkowitz E, Gillen MM, Shearer C, Boone T (2004) Religiosity, sexual behaviors, and sexual attitudes during emerging adulthood. Journal of Sex Research 41: 150-159.

- Sprehe S, Harris G, Meyers A (2008) Perceptions of sources of sex education and targets of sex communication: sociodemographic and cohort effects. Journal of Sex Research 45(1): 17-26.

- Prevention CFDC (2013) Oral Sex and HIV Risk.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.