Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

A Faith-Based Hypertension Control Program for African American Communities: Program

*Corresponding author: Sunita Dodani, Eastern Virginia Medical School (EVMS), EVMS-Sentara Healthcare Analytics and Delivery Science Institute, Virginia, USA.

Received: August 30, 2021; Published: September 09, 2021

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2021.14.001961

Abstract

Objectives: We examined the feasibility of a multi-level, faith-based hypertension (HTN) control program called HEALS in an urban, African American church.

Methods: In a prospective, quasi-experimental design, we implemented a 9-month HTN program. A 3-month intervention (weekly sessions for 12 weeks) followed by a 6-month maintenance program (monthly sessions for 6-months) was delivered by lay church members. The program was offered at the group, individual, and church levels. The primary outcome was a change in systolic blood pressure (SBP).

Results: 52 participants were screened, 51 met the eligibility criteria, and 37 provided written informed consent (N = 37). A retention rate of 92% (34/37) and 73% (28/37) was observed after the 3- and 9-months program, respectively. A SBP reduction of 12.6 mm Hg (p=0.019) and 1.7 mm Hg (p=0.999) were seen from the baseline at 3 and 9-months, respectively. Most SBP changes were seen from baseline to 5 months (p=0.04).

Conclusion: Our study presents a feasible model for HTN control and prevention in a minority community. Though the 3-month intervention showed significant SBP reduction that remained until 5 months, more research is needed to understand the issues of retention and sustainability of community-based programs.

Keywords: Hypertension, African American, church-based, community-based participatory research

Introduction

The disproportionate exposure of low-income, ethnic minority African Americans (AAs) to adverse and unhealthy lifestyle measures contributes to hypertension (HTN) related health disparities [1]. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk continues to be higher in AAs, as compared to their white counterparts, and AAs living in the Stroke Belt of the Southeastern United States have the highest rates of CVD; including, stroke morbidity and mortality due to hypertension (HTN) as compared to any other location in the country [2-5]. Modest but sustained changes in lifestyles related to HTN control and prevention can lead to rapid and substantial decreases in CVD risk. However, lifestyle modifications have not been widely tested among AAs for various reasons; including, limited access to high quality and affordable health care and socio-demographic barriers that may prevent the delivery of health promotion messages in these communities [6]. Targeted approaches, including the empowerment of the community, offer a model to promote a healthy lifestyle and prevent CVD in underserved minority groups.

Proven lifestyle approaches for HTN control include weight loss, exercise, reduced sodium intake, improved diet with Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-style eating pattern, and moderation of alcohol intake [7-10]. These dietary recommendations also apply to those with pre-HTN and a large portion of the general population. In the PREMIER trial, DASH with lifestyle modifications was less effective in AAs with regard to blood pressure (BP) lowering effects [11-13]. Community based participatory research (CBPR) is an essential complement to investigator-led research methods [14]. Several approaches to program development have been used, including top-down and bottom-up approaches [15-16].

Our intervention, Healthy Eating and Living Spiritually (HEALS), modified from PREMIER (including DASH diets), is a faith-based, socio-culturally tailored multi-level behavioral lifestyle intervention for HTN control and prevention among AA adult congregations. We have adopted a bottom-up approach to HEALS intervention development that focuses on clinical experience to maximize the relevance of the intervention and attends to how a program will be applied in real-world settings from its inception [16,17]. The bottom-up approach also provides the opportunity to revise and improve interventions in real-world settings and align them with recommendations for rigorous testing before undergoing highly controlled efficacy/effectiveness trials. The HEALS program tools and instruments validation have already been tested in AA Christian churches and published elsewhere [18].

The objective of this study was to test the feasibility and efficacy

of the HEALS program among high-risk AA members of a church

with uncontrolled HTN. A secondary objective was to use findings

to inform continuous program improvement and prepare for a

rigorous outcomes evaluation. More specifically, the study focuses

on

1. Feasibility of implementing HEALS in an urban low-income

AA Christian church (i.e., how “doable” is the program

implementation in terms of time and workload).

2. Acceptability of the program to implementers and church

participants (i.e., how was the program received and how

responsive it was to church participants’ needs?).

3. Challenges in program implementation and program

adherence. Furthermore, the current study sought to narrow

the research-practice gap by focusing on the communityacademic

partnership and represents a crucial first step to

acquiring empirical support for HEALS. This study is unique

in its CBPR approach to bottom-up program development/

implementation, mixed-methods utilization, and data

collection from multiple respondent groups to provide various

perspectives on program strengths, challenges, and outcomes.

Methods

Study Design, Participants and Setting

This is a prospective, quasi-experimental, pre-post single-arm intervention design study on high risk AAs with HTN in an urban, low-income neighborhood in an AA church in Jacksonville, Florida. The complete two-year study period included several program components that were described in detail elsewhere.18-20 Briefly, several activities were completed before the implementation of the 9-month HEALS program, including the establishment of a community advisory board (CAB), three months of HEALS intervention development, focus groups, and training of community health advisors (CHAs) as program leaders [15,17-19].

HEALS Intervention

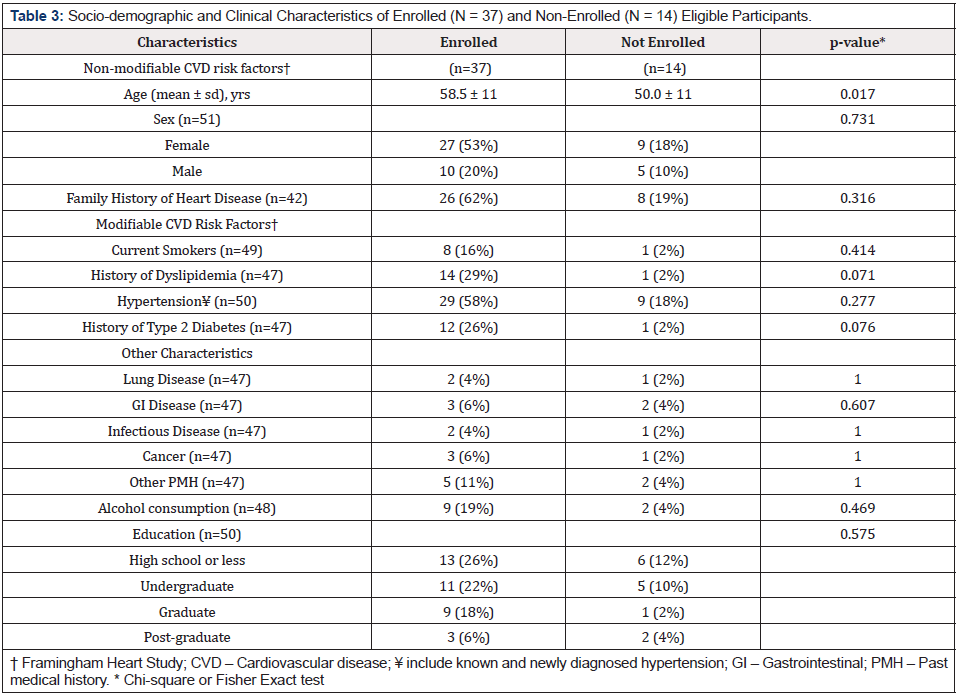

Details on HEALS program development are published elsewhere [20-23]. Briefly, with the input from the CAB, academic experts, and Christian church pastors, the 12-week HEALS intervention sessions were developed and modified from the 18- week PREMIER lifestyle program (including DASH diets) into a multi-level, culturally tailored, faith-based, and faith-placed group intervention (Table 1), theoretically grounded in the Social Cognitive Theory [24-26]. Members of the original DASH and PREMIER teams and CAB were involved in the modification and development of HEALS. CAB members selected the spiritual themes and scriptures to frame the three themes of the intervention: nutrition, increased physical activity (PA), and behavioral change. Additionally, they wrote messages to be included in the program to support and promote health behavior change. The spirituality component was seen as a source of emotional support, a positive influence on health, and contributing to life satisfaction.

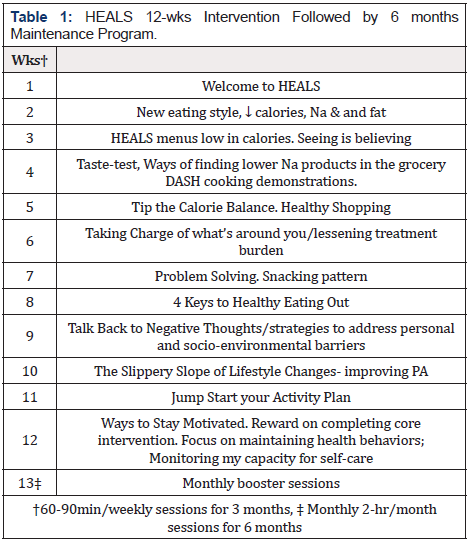

HEALS program goals are provided in (Table 2). Sessions 1-8 presented goals for the behavioral lifestyle change, gave fundamental information about modifying energy intake and increasing energy output, with instructions for participants to monitor their food intake and PA. The latter 4 sessions focused on the psychological, social, and motivational challenges involved in maintaining these healthy lifestyle behaviors in the long term. The intervention was offered at three levels; church level (offered by the church pastor), group, and individual level (offered by trained church lay members called church health advisors-CHAs) [18,20,27]. Four CHAs were nominated by the pastor to be the program leaders [18]. There were no requirements for prior training in health education or health care, but the importance of CHAs being viewed as role models among program participants was emphasized. The HEALS team conducted a 10-hour training workshop for CHAs to familiarize CHAs with the HEALS program. CHAs were also trained on skills of obtaining anthropometric measurements as well as pedometer use. In light of the required commitment and training, CHAs were provided with a small stipend to attend the training workshop and conduct HEALS sessions [21,23].

Goals and Anticipated Outcomes

Adaptation Of DASH Diet to A Culturally Tailored HEALS Diet

The barriers to adopting the DASH diet plan are the frequent consumption of “soul food”, energy-dense fast foods, and convenience foods (often high in fat and sodium) in AA communities. Modifications in the DASH diets were made to generate a culturally appropriate diet plan without compromising the integrity of DASH caloric contents. The HEALS diet discusses correct practices and misconceptions about personal eating habits and the DASH diet plan. For example, discussions regarding the extent to which traditional cuisines such as “soul food” and the consumption of fast food and convenience foods affect the attainment of the DASH dietary goals were made during the sessions as well as during healthy cooking demonstrations. Adaptation of the DASH diet to the HEALS diet included: a) developing alternative methods of cooking food that did not compromise the taste; b) reading labels with nutrition facts to limit total fat, saturated fat, sodium, and sugar; c) reducing trips to fast food establishments and/or making wise choices there; and d) other lifestyle factors that support DASH principles, such as physical activity (PA).

6-Month HEALS Maintenance Program

Monthly booster sessions were also delivered by CHAs post intervention for 6 months. These informal sessions were developed and modified from the PREMIER maintenance program to endorse the 3-month education received and helping participants to overcome barriers to healthy lifestyles. Many of these sessions were offered in the discussion format.

Implementation of 9-Months HEALS Program

With the pastor’s support, a health fair was arranged at the church and HEALS team, including CHAs, recruited eligible participants for the 9-month HEALS program. The eligibility criteria included (a) self-identified AA church members, aged 18-75 years, who provided written informed consent, and (b) known HTN, and/ or on HTN medications, or pre-HTN as per JNC-7 classification.7 All other members were excluded.

Detailed medical histories were obtained on sociodemographics, co-morbidities, medication history, and lifestyle habits, including diet, exercise, smoking, and alcohol. Twenty-four hour (24-hr) dietary recalls were used to assess the participants’ change in dietary intake and adherence to the program’s dietary guidelines (Table 2) [28]. Additionally, participants were provided with food log diaries to report weekly on their consumed food during the first 12 weeks. Food log diaries were provided as a method of self-diet monitoring as well as an additional tool for nutrition data collection. No food log diaries were provided in the 6-month maintenance program. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) was also completed at baseline and at 9 months to measure intake of daily and/or weekly cooked or canned beans, 100% fruit juice, fruits, and dark green, orange-colored, and other vegetables [29]. PA was assessed using a 7-day PA recall (PAR) at baseline, 3 and 9 months of intervention [30]. Self-reporting for PA can be subjective, we, therefore, decided to accompany the PA assessment with pedometer usage and every participant was provided with a basic pedometer. The CHAs distributed pedometers to participants after enrollment and explained how to operate and when to wear them. In addition, CHAs were given education during the training workshop on the importance of brisk walking for at least 150 minutes per week. All participants were given clear instructions, and the research team briefly described the study.

Program Sessions

Weekly group sessions were delivered by CHAs every Sunday

after church services under the supervision of the HEALS research

team for 12 weeks. Make-up sessions were also conducted on a

different day by CHAs for participants who could not attend Sunday

sessions. Monthly maintenance sessions were conducted in an

informal group setting. Participants were given the opportunity

to endorse/recap the essential components of HEALS program

and received tips for maintaining healthy behaviors. Based on the

pastor’s recommendation, the maintenance sessions took place at

the church every month for 6 months post intervention on every

first or 4th Sunday of a month. Prior to the start of every session,

the following anthropometric measurements were performed and

documented by the CHAs under research team supervision:

a) Weight, using a physician’s office calibrated scale.

b) Height, using a wall-mounted stadiometer.

c) Waist circumference (at the level of 2 cm above the umbilicus)

using a standard measuring tape. Body mass index (BMI) was

calculated (weight in kilograms/height in meters squared).

An automatic BP monitor (Omron BP710 make) was used with two cuff sizes (normal adult and overweight). The CHAs and the study coordinator performed BP measurements in the presence of the research team, per JNC-7 recommendations. Two BP measurements separated by at least 5 minutes at each session were obtained in a calm and quiet place. Study participants who met BP eligibility criteria had another set of BP measurements on a different day, and those who fulfilled the requirements on both days were included. For each study day and at every assessment point, BP was the mean of two available measurements. Mean BP readings were used for data analysis.

Exercise sessions were conducted at the church by a YMCAcertified fitness instructor at the end of the HEALS sessions for 12 weeks. These sessions focused on increasing participant’s PA levels using various strategies such as group jogging, brisk walking, yoga, dancing, etc. Similarly, in collaboration with the local farmers market, periodic supplies of fresh produce were made available at low cost at the end of the Sunday sessions for the first five months.

Statistical Analysis and Sample Size

The primary outcome was a quantitative change in SBP from baseline (0) to three months. Secondary outcomes included quantitative changes in Diastolic BP (DBP), weight, nutrition intake, particularly sodium intake, and PA from baseline (0) to 3 and 9 months. As this was a feasibility/efficacy study, a convenience sample of 37 church participants was recruited without a specific sample size target. Results obtained from this study will help develop a powered randomized controlled clinical trial. Statistical analyses and modeling were conducted using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Continuous variables were described by using means, standard deviations (SDs), and medians. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics between groups were compared using Kruskal-Wallis tests or t-test for numeric or ordinal variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Outcome variables were analyzed using repeated measure ANOVA tests. Missing information was handled by the listwise deletion approach, which drops only that point where data was missing and all other data from other time points were included. Tukey adjustments were performed for multiple pairwise comparisons to assess significant pairs. Participants’ nutrient intake data (secondary outcomes) were analyzed on USDA’s Myplate tracker and verified with nutritionist Pro software. SPSS Version 22 software was used for nutrition data analysis to obtain descriptive and T-test statistical analyses on nutrition related outcomes were completed. The retention rate was defined as the percentage of participants attending 8 or more sessions out of 12 sessions during the 3-month HEALS intervention and attending 4 or more sessions out of 6 maintenance monthly sessions during the HEALS maintenance program.

Results

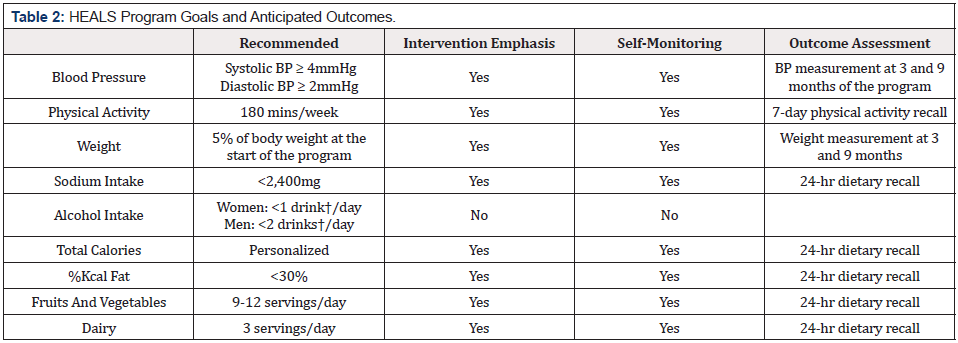

Of the 52 church members screened, 51 met the eligibility criteria, and 37 provided written informed consent and were enrolled in the study (n = 37). (Table 3) provides socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of enrolled and non-enrolled eligible participants. Except for age, there was no statistical difference in socio-demographic and clinical characteristics between the enrolled and non-enrolled groups. Of the enrolled participants, the mean age was 58.5 (± 11), an older group compared to non-enrolled participants (p = 0.017), 27 (73%) were females, and 29 (78%) had a history of HTN with eight (22%) newly diagnosed HTN or pre- HTN based on JNC-7 criteria. In the secondary analysis (not shown in Table 3), of 29 with HTN, only four had BP control of 120/80 or below, as defined in the recent SPRINT study [31,32].

Table 3: Socio-demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Enrolled (N = 37) and Non-Enrolled (N = 14) Eligible Participants.

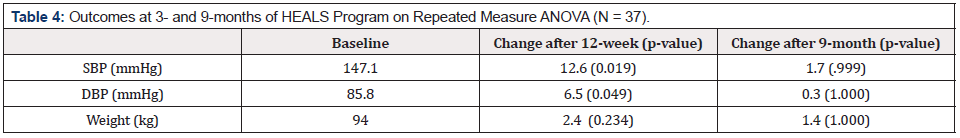

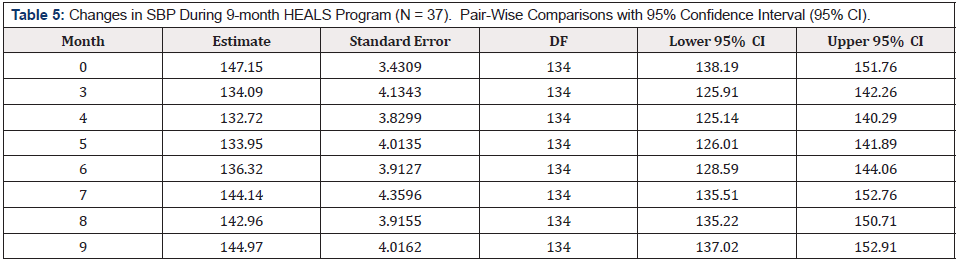

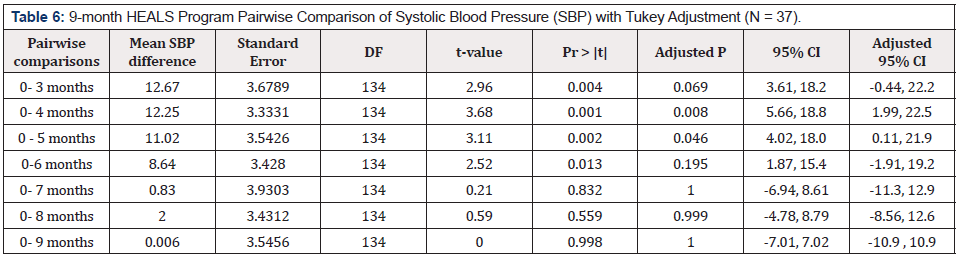

Moreover, of 29, 15 (52%) were on anti-HTN drugs and 6/15 (40%) on three anti-HTN drugs, yet uncontrolled HTN. A retention rate of 92% (34/37) and 73% (28/37) was observed after 3 and 9 months of the program, respectively. At the end of the three months intervention, there were significant changes for both SBP and DBP, more so for SBP (Table 4). A reduction of 12.6 mm Hg (p = .019) in SBP and reduction of 6.5 mm Hg (p = .049) in DBP was seen post intervention (after three months) from the baseline. During the 6-month maintenance phase, BP continued to reduce until month 5 and gradually increased (Table 5 & 6). At 9 months, SBP was 145.5 mm Hg (p = .999). After Tukey adjustment (Table 6), most SBP reductions were seen from the baseline to 4 months (p = .008) and from baseline to five months (p = .04).

Nutritional Changes (from Baseline to 9-months)

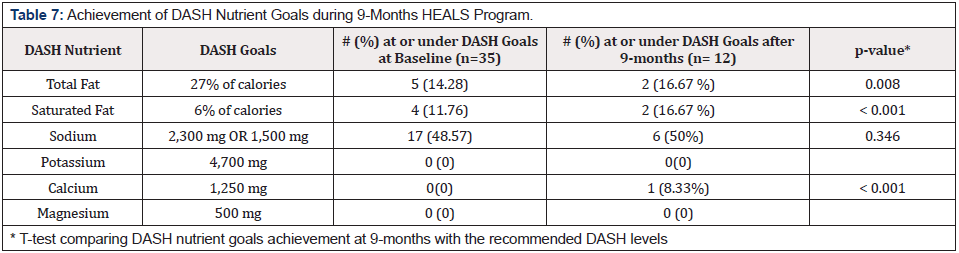

Positive trends towards healthy eating were also observed at the end of the 9-month HEALS program; however, changes were not statistically significant due to the small sample size at each point of completed analysis (Table 7). Of the 37 participants, 35 provided completed 24-hr dietary recalls at the baseline, and 12/35 completed them at 9 months. The nutrient analysis showed that at baseline (0 month), 5/35 (14.28%) and 4/35 (11.76%) of participants met DASH recommendations for total fat and saturated fat intake, respectively. At the end of the 9 month HEALS program, 2/12 (16.67%) met the DASH recommendations of reducing total and saturated fat intakes 27 and 6 percent of total calories or less (Table 7) [26]. Of the 12 participants completing BRFSS Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) at the end of 9 months, 8.33% of participants met the recommendations for calcium and was statistically significant (p < .001).

Regarding DASH recommendations for sodium intake, at baseline, 17/35 (48.57 %) of participants were in line with DASH recommendations to consume 2,300 mg of sodium or less per day (Table 7). At the end of 9 months of HEALS program, 6/12 (50%) were in line with DASH recommendations, however no significant difference was found between the DASH recommended goal for sodium and participants reported mean consumption of sodium at the end of 9 months (p= .346). Less success was also observed in fat consumption. At the end of the 9 months, the mean total fat percent consumed by participants was 11.58% higher than the DASH recommended goals (p <= .001). Similarly, the mean intake for saturated fat was also 6% higher (p < .001) compared to the recommended DASH levels.

Paired T-Test analyses for total calories, total fat, saturated fat, calcium, sodium, magnesium, and potassium on 12 participants who completed both baseline and 9-month 24-hr dietary recalls revealed no statistical significance from baseline to 9 months. For all the nutrients mentioned previously, a steady decrease in intake was noted, but due to a small number of respondents, it was not statistically significant (not shown on the tables). Similar but non-significant trends were also seen on completed BRFSS FFQs regarding the intake of daily and/or weekly cooked or canned beans, 100% fruit juice, fruits, and dark green, orange-colored, and other vegetables at the end of the 9 months compared to baseline.

Discussion

Disparities in health and health care are national concerns, and our lack of progress in reducing them among racial and ethnic minorities remains a major challenge. The current study represented a faith community-academic collaboration, which aimed to evaluate a community-developed intervention’s feasibility, acceptability, preliminary outcomes, and promise. This faith community-academic partnership adopted a bottom-up approach to evaluating HEALS in an urban low-income Christian church. The advantage of a bottom-up approach is that it attends to issues of program relevance to underserved populations, limited community resources, and program sustainability from the onset. Overall, the study findings provide preliminary evidence of the acceptability of the HEALS program with a high participant retention rate at the end of 9 months.

A church pastor participated in the program as an eligible participant and reported high levels of satisfaction as well as indicated that he would recommend the program to other Christian churches. The HEALS Program was not designed to be a stand-alone program that an external entity would conduct in a church setting. Instead, HEALS was designed to require church resources, commitment from church staff, and integration into the church’s environment. Thus, it was essential that all partners were committed to program success and that church staff, such as pastors and CHAs, were motivated to implement a program that they believed would ultimately improve participants’ health and quality of life. Consistent with the principles of CBPR, results were shared with the church leadership and implementers as available to allow for timely program improvements and preparation for a rigorous outcomes evaluation. Below are some of the program strengths, challenges, and opportunities for program improvement for more desirable outcomes. We also provide recommendations on improving/ revising the screening processes, timelines, curriculum, and training.

Program Strengths

The HEALS program was delivered by trained lay health advisors-CHAs, which offers a unique opportunity from the policy standpoint, involving community members in the chronic care disease management programs with academic healthcare providers for improved acceptance and outcomes. The concept of evaluating the efficacy of the PREMIER modified lifestyle interventions in the real-world community-based settings, using a collaborative church community-academic partnership approach, is innovative and can facilitate the translation of research into public health practice by empowering the communities. Another innovative component of HEALS was the development of individualized health goals by CHAs for participants that were endorsed during individual communications. Though the concept of training community members is not new, understanding the roles, functions and level of involvement of trained community members in improving the health of a community is essential.

The HEALS program may set a model of a feasible and functional CHA-led behavioral lifestyle program where CHAs interact with participants as a group and meet with them to set individual goals towards HTN control. CHAs, after training, incorporated essential HEALS program skills into both the group and individual sessions that enabled participants to explore their perceived barriers toward behavior change, learned alternative methods of making changes in their daily living, and built motivation and confidence to change, with a commitment to such change, that is in line with social cognitive model ingredients [33]. Although conducted as a smallscale feasibility/efficacy pre-post single-arm study, significant effects were seen for BP reduction up to five months. The retention rate (percentage of group sessions attended by participants) in our study was higher than seen in the previous community-based DASH trials, further demonstrating the feasibility of our model [34-36]. One reason for the high retention rates of 92% and 73% after three and 9 months of the HEALS program, respectively, could be a long-standing partnership between the institution and faith communities. This church community-academic partnership had already developed a robust partnership by the time the 9-month program began, resulting in improved acceptance and implementation of the program.

However, HEALS reach, as defined by RE-AIM model, was low considering that the adult members of the congregation numbers to about 400 persons with a high prevalence of HTN (based on the pastor’s report) [37]. The formal process evaluation was not performed and will be included in future HEALS effectiveness studies. In general, recruitment and retention of racial/ethnic minorities, particularly AAs and Hispanics, into clinical trials continues to be a challenge. Yet other factors are important to consider, such as the lack of studies occurring in racial/ethnic minority serving institutions, limited awareness of ongoing studies, work/family, socio-cultural barriers, and the prevalence of co-morbid conditions. Regardless of the challenges, the inclusion of minorities in research is important to ensure that results are relevant and generalizable. Some of the present study’s strengths, in addition to significant BP outcomes, were improved retention rates at the end of the 9-month program and strong community willingness and support for participation.

Program Challenges and Opportunities for Improvements

Though positive results were seen with BP control in the first 5 months, we faced several challenges. First, recruiting church members to participate in the study was a challenge. Although this church had more than 400 adult members, regular and active members were around 100. Though the original recruitment plan used church bulletin announcements and flyers from the CAB and church pastors to church members, we had difficulty disseminating information since the agendas were made several months in advance. Additionally, the days of the health fairs (participants’ screening) were set after consulting the church pastor, coincided with pre-planned evening events at the church. Therefore, it was difficult for church members to come twice and stay for the free health screening for HEALS program recruitment. This can be improved by increasing awareness of the program and program goals through proper program marketing in the church and the neighborhood with the support of the church leadership.

Second, there were data completion issues due to incomplete nutrition and PA data. Although pedometers were provided to all participants and the use of pedometers with proper documentation of reading pedometers was illustrated, the majority of participants did not wear pedometers daily. Therefore, very limited information was obtained, and additional analysis was not performed. Similarly, only a few participants completed the log diaries, 24-hr dietary recalls, and BRFSS FFQs at three and 9-month endpoints, and among those, many questionnaires were incomplete. For future studies, particular emphasis will be given to pedometer use, reading and documentation of pedometer readings on the log diary, and repeated reminders to participants on the regular use of pedometers as a part of their daily living routine.

Third, there were difficulties contacting participants for maintenance and booster sessions. We found some participants were extremely hard to reach due to work hours and disconnected phone numbers. Further, most participants did not use emails and therefore were contacted via a preferred phone number provided on the baseline questionnaires and at preferred times. If numbers were disconnected, we contacted respective CHAs and pastors to contact the participant at the church service to get the new phone number or any additional information on the participant’s status. However, future studies need to take into consideration these challenges and address them for improved program participation. Fourth, there were issues with waist circumference measurements performed by the CHAs, and data analysis showed considerable variations in waist circumference at both 3 and 9-month endpoints. Therefore, waist circumference data was not accurate and was not included in the study results. In future studies, careful attention will be made to train, test and retest proper education on waist circumference measurements by CHAs with repeated refresher sessions and supervision during the program.

Fifth, the issue of maintaining health behaviors past the 3

months of the HEALS intervention and sustaining the program as

described above. One reason for an increase in BP after 5 months

could be the discontinuation of F&Vs supply. Program sustainability

and maintenance of behavior by study participants in churches can

be improved through collaborative efforts between the churches,

local produce farmers and academic institutions. Improved

planning of formal booster sessions and post intervention

maintenance activities at churches on a regular basis may also be

helpful. Initiatives may include but not limited to

a) Establishing a long-term relationship with the farmers

market for regular supplies of fresh produce at low cost at the

church.

b) Serving healthy meals, healthy snacks, and other healthy

choices at church.

c) Maintaining a HEALS program committee, governed

by CHAs as a formal committee of the church to endorse healthy

behaviors.

d) Continuing to provide support through pastoral sermons

and personal testimonies; and

e) Continuing to improve health policies in partnership with

church health ministries. Clearly, resources, such as time, energy,

support, committed staff, and funding, are critical elements for

churches to maintain such CBPR projects, especially in the face of

competing priorities. In the current era of limited and competing

funding, it has been a significant challenge for the researchers to

nourish and sustain these resources for the future of church-based

health promotion. Strategic dissemination by agencies such as the

National Institute of Health (NIH) and public-private partnerships

with faith-based organizations and interested sponsors are

potential avenues for establishing and maintaining the capacity for

churches to adopt and implement evidence-based health promotion

programs that can ultimately reduce health disparities.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Despite limitations, there are important strengths of this study. Unlike typical pilot studies, this study obtained data from a lowincome ethnic minority AA Christian church, adding credibility to the preliminary outcomes. Given the diverse and acute behavioral health needs in the context of scarce resources in underserved communities, CBPR with “bottom-up” research that refines and tests innovative, community-developed programs may offer an efficient, acceptable, and sustainable approach to dissemination/ implementation research. The current study supports the value of church community-academic partnerships- that must be built on relationships of trust, shared vision, and mutual capacity building, with genuine community engagement at multiple levels. The lessons learned from this study are critical for collaborating with church communities and working in other community settings and on other health issues. If the HEALS model proves to be a successful CBPR HTN control program, the findings will provide much-needed information on the translation and sustainability of these approaches in church-based settings with the potential for dissemination to other AA churches.

Human Subject Statement

All procedures performed in this present study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Florida research committee and Institutional Review Board as well as with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Of the 52 participants were screened, 51 met the eligibility criteria and 37 provided written informed consent (N = 37) consistent with the requirements of the institutional review board, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (“HIPAA”)

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure Statement

This study was supported by internal funding and no outside funding and/or grants was received. Dr. Sunita Dodani declares that she has no other conflicts of interest. Dr. Claudia Sealey-Potts declares that she has no other conflicts of interest. Dr. Sahel Arora declares that she has no other conflicts of interest. Mr. Joshua Edwards declares that he has no other conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that all authors have contributed significantly to this study, and that all authors are in agreement with the content of the manuscript. Percentage of contribution: Sunita Dodani, Claudia Sealey-Potts, and Sahel Arora contributed to the conduction of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and wrote the manuscript. Sunita Dodani contributed to the design and conduction of the study and wrote the manuscript. Sunita Dodani is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Mr. Joshua Edwards edited and formatted the manuscript.

References

- Control CfD (2017) Prevention BRFSS survey data and documentation.

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, et al. (2011) heart disease and stroke statistics-2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 123(4): e18-e209.

- Howard VJ, Woolson RF, Egan BM, Nicholas JS, Adams RJ, et al. (2010) Prevalence of hypertension by duration and age at exposure to the stroke belt. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension 4(1): 32-41.

- Kleindorfer DO, Khoury J, Moomaw CJ, Alwell K, Woo D, et al. (2010) Stroke incidence is decreasing in whites, but not in blacks: a population-based estimate of temporal trends in stroke incidence from the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky stroke study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation 41(7): 1326-1331.

- Olives C, Myerson R, Mokdad AH, Murray CJ, Lim SS, et al. (2013) Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in United States counties, 2001–2009. PloS one 8(4): e60308.

- Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, Nieman CL, Joo JH, et al. (2016) Effects of Community-Based Health Worker Interventions to Improve Chronic Disease Management and Care Among Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Public Health 106(4): e3-e28.

- The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

- Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, Fonarow GC, Lawrence W, et al. (2014) An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol 63(12): 1230-1238.

- Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, Fonarow GC, Lawrence W, et al. (2014) An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension 63(4): 878-885.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL (2014) evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). Jama 311(5): 507-520.

- Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Cooper LS, Obarzanek E, et al. (2003) Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. Jama 289(16): 2083-2093.

- Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Morton DS, Stevens VJ, et al. (2006) Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 144(7): 485-495.

- Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Lin P-H, Cooper LS, Young DR, et al. (2007) Effects of individual components of multiple behavior changes: the PREMIER trial. American journal of health behavior 31(5): 545-560.

- Pinto RM, Witte SS, Wall MM, Filippone PL (2018) Recruiting and retaining service agencies and public health providers in longitudinal studies: Implications for community-engaged implementation research. Methodological Innovations 11(1): 2059799118770996.

- Hawk M (2013) The Girlfriends Project: Results of a pilot study assessing feasibility of an HIV testing and risk reduction intervention developed, implemented, and evaluated in community settings. AIDS Education and Prevention 25(6): 519-534.

- Lemmens KMM, Nieboer AP, Rutten-Van Mölken MPMH, van Schayck CP, Spreeuwenberg C, et al. (2011) Bottom-up implementation of disease-management programmes: results of a multisite comparison. BMJ Quality & Safety 20(1): 76-86.

- Dell CA, Duncan CR, DesRoches A, Bendig M, Steeves M, et al. (2013) Back to the basics: identifying positive youth development as the theoretical framework for a youth drug prevention program in rural Saskatchewan, Canada amidst a program evaluation. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy 8(1): 36.

- Dodani S, Beayler I, Lewis J, Sowders LA (2014) HEALS Hypertension Control Program: Training Church Members as Program Leaders. Open Cardiovasc Med J 8: 121-127.

- Dodani S (2011) Community-based participatory research approaches for hypertension control and prevention in churches. Int J Hypertens 273120.

- Dodani S, Arora S, Kraemer D (2014) HEALS- A Faith based hypertension control program for African Americans: Study. Scientific An Academic Publisher 5: 95-100.

- Dodani S, Arora S, Kraemer D (2014) HEALS: A Faith-Based Hypertension Control Program for African Americans: A Feasibility Study. Scientific An Academic Publisher 4: 95-100.

- Dodani S, Beayler I, Lewis J, Sowders LA (2014) HEALS hypertension control program: training church members as program leaders. The open cardiovascular medicine journal 8: 121.

- Dodani S, Sullivan D, Pankey S, Champagne C (2011) HEALS: a Faith-based hypertension control and prevention program for African American churches: training of church leaders as program interventionists. International Journal of Hypertension 2011.

- Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Cooper LS, Obarzanek E, et al. (2003) Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association 289(16): 2083-2093.

- Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Lin P-H, Cooper LS, Young DR, et al. (2007) Effects of individual components of multiple behavior changes: the PREMIER trial. American Journal of Health Behavior 31(5): 545-560.

- Moore T, Svetkey L, Lin P-H, Karanja N, Jenkins M (2003) Dash Diet for Hypertension. Pocket Books

- Dodani S, Sullivan D, Pankey S, Champagne C (2011) HEALS: A Faith-Based Hypertension Control and Prevention Program for African American Churches: Training of Church Leaders as Program Interventionists. International journal of hypertension 2011: 820101.

- Carroll RJ, Midthune D, Subar AF, Shumakovich M, Freedman LS, et al. (2012) Taking advantage of the strengths of 2 different dietary assessment instruments to improve intake estimates for nutritional epidemiology. American journal of epidemiology 175(4): 340-347.

- CDC (2016) Center for Disease Control BRFSS Questionnaires.

- Blair SN, Haskell WL, Ho P, Paffenbarger Jr RS, Vranizan KM, et al. (1985) Assessment of habitual physical activity by a seven-day recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. American journal of epidemiology 122(5): 794-804.

- Cushman WC, Whelton PK, Fine LJ, Wright Jr JT, Reboussin DM, et al. (2016) SPRINT Trial Results: Latest News in Hypertension Management. Hypertension 67(2): 263-265.

- Kjeldsen SE, Oparil S, Narkiewicz K, Hedner T (2016) The J-curve phenomenon revisited again: SPRINT outcomes favor target systolic blood pressure below 120 mmHg. Blood pressure 25(1): 1-3.

- Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory: Prentice Hall 617.

- Rankins J, Sampson W, Brown B, Jenkins-Salley T (2005) Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) intervention reduces blood pressure among hypertensive African American patients in a neighborhood health care center. J Nutr Educ Behav 37(5): 259-264.

- Scisney-Matlock M, Glazewki L, McClerking C, Kachorek L (2006) Development and evaluation of DASH diet tailored messages for hypertension treatment. Applied nursing research: ANR 19(2): 78-87.

- Whitt-Glover MC, Hunter JC, Foy CG, Quandt SA, Vitolins MZ, et al. (2013) Translating the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet for use in underresourced, urban African American communities, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis 10: 120088.

- Glasgow RE, Mc Kay HG, Piette JD, Reynolds KD (2001) The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient education and counseling 44(2): 119-127.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.