Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Predictors of Knowledge and Practice Related to Covid-19 Among Women of Karachi, Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Study

*Corresponding author: Rahil Barkat, Indus Hospital Research Center, Indus Hospital & Health Network, Karachi, Pakistan.

Received: November 02, 2021; Published: November 18, 2021

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2021.14.002038

Abstract

Introduction: In recent times, coronavirus has become a major health hazard around the world, and it leads to considerable human mortality and morbidity. The control of communicable diseases depends majorly on the behavior, practices, attitudes, and knowledge of the local people. The aim of this study is to explore the predictors of knowledge and practices related to the Covid-19 pandemic among the sample of Pakistani women.

Methodology: It was a cross-sectional study conducted in Karachi, Pakistan, after getting ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Liaquat National Hospital, Karachi. The required sample size was 410. Participants were enrolled in the study using a non-probability convenient sampling technique.

Results: A total of 431 participants completed the questionnaire. The mean age of study participants is 30.08 (+/-10.49) years. Educational status, marital status, and presence of comorbidity are the predictors of a good knowledge score. Moreover, educational status, having a history of COVID-19, and good knowledge scores were significantly associated with adequate practice among women.

Conclusion: Overall, the majority of the women who participated in the study had poor knowledge and followed inadequate practice during the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite all of the precautions, it appears that the only way to defeat this highly infectious disease is for organized and continuous efforts to raise public awareness of the disease. Furthermore, when conducting daily responsibilities, workers should adhere to government-issued standard operating procedures.

Keywords: Covid-19, Women, Knowledge, Practice, Pakistan

Introduction

In recent times, coronavirus has become a major health hazard around the world, and it leads to considerable human mortality and morbidity. In a short time period, the COVID-19 has spread around the world. This infection has been spread to more than 200 countries worldwide and infected nearly 30 Million people, causing nearly 1 million deaths [1]. In Pakistan, the first positive case of COVID-19 was identified on 26 February 2020. The government of Pakistan shut down all leisure spots, mosques, religious schools, and educational institutions to deal with the spread effectively. All services and meetings were postponed, and a complete lockdown was implemented in the country on 23 March 2020 [2]. In order to deal with issues that are associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to incorporate non-medical measures, including social distancing and wearing face masks, and imposing travel restrictions [3]. The actual cause of mortality caused by this virus is still unknown, and the globe is suffering as a result of it. This pandemic has put enormous strain on healthcare systems, economies, and governments around the world. The avoidance of this deadly calamity will require effective responses from health professionals and governing organizations [4].

It is having misconceptions and a lack of knowledge about the disease that enhances the risk of Covid-19 and raises the burden on the health care system further. Literature has shown that certain positive behaviors are not properly following by individuals, such as not wearing gloves and removing masks while talking to people [5]. Change in behavior is quite challenging, and also, change in behavior can be an unstable and unsteady process that requires time and knowledge for understanding things and their significance. The control of communicable diseases depends majorly on the behavior, practices, attitudes, and knowledge of the local people [6]. Controlling the disease requires careful adherence to preventative measures to prevent it from spreading to the people. People have been overburdened by the influx of information from various sources, particularly social media; as a result, they are perplexed and impatient to discover true information [7]. Understanding public knowledge, attitudes, dedication, compliance with, and acceptability of measures that touch their everyday life in a variety of ways, particularly mentally, physically, and socially, is critical [8].

Analyzing the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of the general public could help to acquire this insight. The present study has explored the predictors of knowledge and practices related to the Covid-19 pandemic among the sample of Pakistani women and explores common misconceptions among them. The results of this study will help the authorities in updating the awareness campaigns and to remove malpractices and misconceptions related to COVID-19 that may help in better management of the disease and also the development of effective policies in curtailing the pandemic. The aim of this study is to explore the predictors of knowledge and practices related to the Covid-19 pandemic among the sample of Pakistani women.

Methodology

It was a cross-sectional study conducted in Karachi, Pakistan, after getting ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Liaquat National Hospital, Karachi. The Raosoft sample size calculator was used to calculate the sample size, considering the confidence level of 95%, the margin of error of 5%, and the population size of 1000000. The required sample size was 410. Participants were enrolled in the study using a non-probability convenient sampling technique. Verbal consent was taken from all participants, and study objectives and background were briefly explained to them, and they were encouraged to ask any question relevant to the study before proceeding. A questionnaire was developed with the help of the World Health Organization (WHO) myth-buster document and a published study [9-10]. The questionnaire was developed in English and then translated into the local language (Urdu). Later, it was backtranslated into the English language by the bilingual expert. A questionnaire was modified based on their suggestions. One epidemiologist and one general physician from Liaquat National Hospital validated the questionnaire. A pilot study was conducted before initiating the final study on 40 women from the general population to assess the interpretation and convenience of the questionnaire, and data of those 40 participants were not included in the final analysis. The reliability of the questionnaire was 0.73 (Cronbach’s Alpha). All women were included in the study having an age of 18 years or more and are willing to participate in the study. Study participants were enrolled in the study from the Liaquat National Hospital, including patients, attendants, students, and health care professionals, to get a diverse sample in order to make findings more generalizable.

Study Questionnaire

The questionnaire used in the present study had four parts. The first part comprised of demographic characteristics of participants, including age, marital status, employment status, education, and any comorbidity. The first section also assessed information sources using by participants to get information about COVID-19. The second section assessed knowledge that comprised seven questions. The third section assessed misconceptions comprised of 10 questions, and the last section was related to practice in covid-19 contained fives questions. Questions related to knowledge were true/false types or yes/no types. For every correct answer, one point was awarded, and an individual score less than 75% was considered to have poor knowledge, and participants having a score of 75% or more had good knowledge. The Person practice score ranged from 0 to 10; a score of 6 or more was considered adequate, while a score of less than six was considered inadequate [9].

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was done by using STATA software version 16.0. For continuous variables, mean and standard deviation were calculated, while categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage. To determine the predictors of good knowledge and adequate practice among the women of Karachi, Pakistan, univariate analysis was done using the Chi-square test of independence. For univariate, a cut-off of p-value was kept at 0.25. Variables significant in univariate analysis were used to make the final model keeping knowledge score and practice as outcome variables. For this, multivariable logistic regression was used, and adjusted odds ratios were computed. For multivariable logistic regression, a cut-off of the p-value was kept at 0.05.

Results

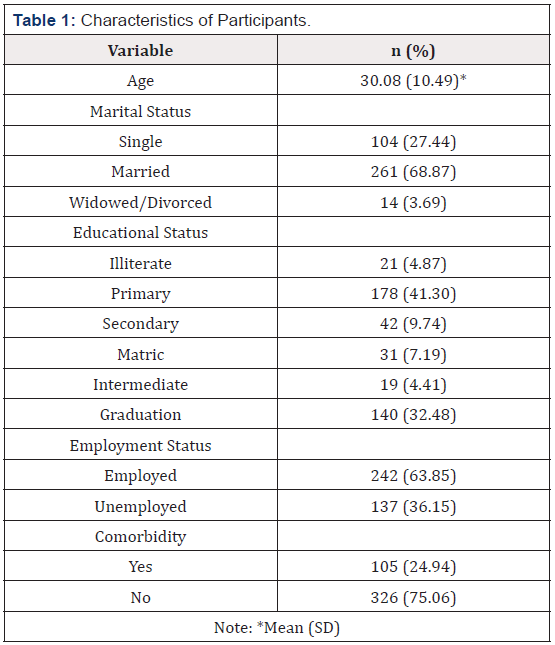

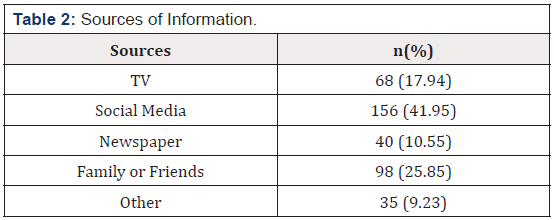

A total of 431 participants completed the questionnaire. The general characteristics of the respondent are shown in Table 1. The mean age of study participants is 30.08 (+/-10.49) years. Most women who participated in the study were married (68.87%), while more than half of the participants were employed (63.85%). Among respondents, the sources for getting information on Covid-10 are shown in Table 2. The most common source of information is social media (41.95%), followed by family or friends and television that are 25.85% and 17.94%, respectively. Nearly one-fourth of women reported comorbidity, and the most common comorbidity was diabetes (22.3%) and hypertension (15%) (Table 1 &2).

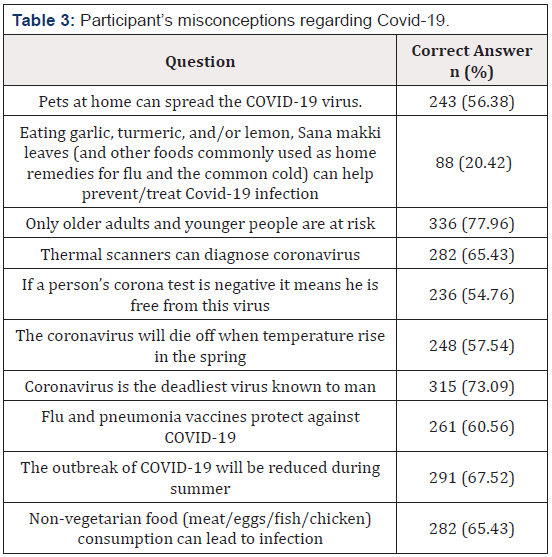

Some of the common misconceptions among women related to COVID-19 were “If a person’s corona test is negative, it means he is free from this virus,” as 45.24% of women believe this and 43.52% of women believe that “Pets at home can spread the COVID-19 virus” and 39.44 women believed that “flu and pneumonia vaccines protect against this virus” as shown in Table 3 (Table 3).

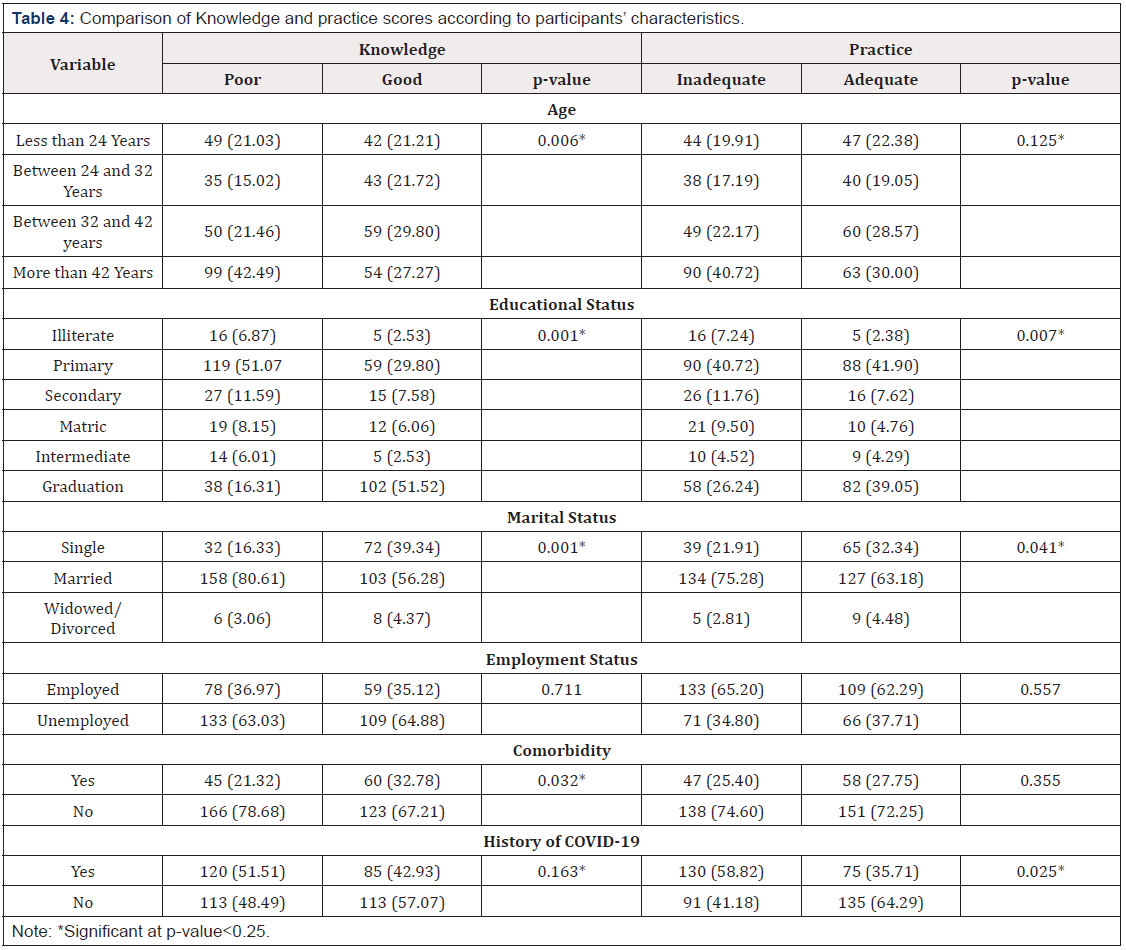

Less than half of the study participants (45.94%) had good knowledge of COVID-19. Similarly, almost half of the study participants (48.72) had poor practice during Covid-19. Table 4 shows the results of Univariate analysis. Significant differences in knowledge scores were found according to age group (P-value=0.006), educational status (P-value=0.001), marital status (P-value=0.001) and presence of any comorbidity (P-value=0.032). Significant differences in practice scores were observed between age groups (P-value=0.125), educational status (P-value=0.007), marital status (P-value=0.041), and history of Covid-19 (P-value=0.025) (Table 4).

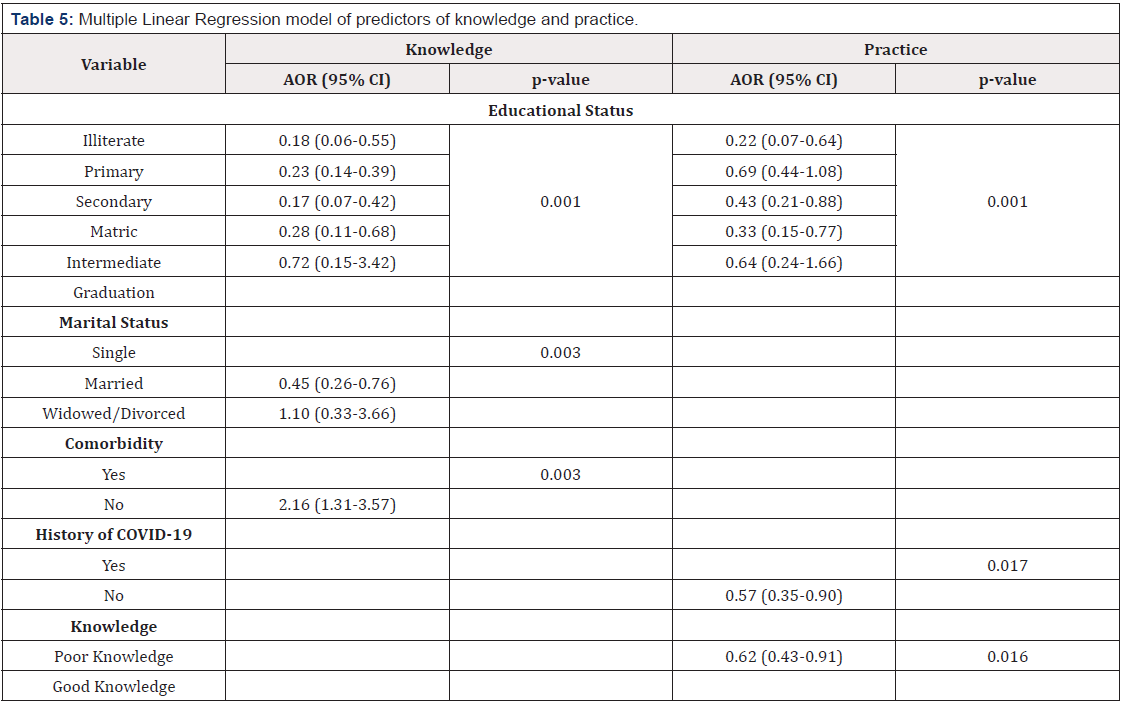

Multiple logistic regression analysis was done to determine the predictors of good knowledge score and adequate practice related to COVID-19. Educational status, marital status, and presence of comorbidity are the predictors of a good knowledge score. It means that women with at least graduation have good knowledge scores as compared to illiterate women and women with primary education. Besides this, single women have a good knowledge score as compared to married women. Lastly, women with at least one comorbidity had a good knowledge score as compared to their counterparts, as shown in Table 5. Moreover, educational status, having a history of COVID-19, and good knowledge scores were significantly associated with adequate practice among women. Women with at least graduation are more likely to follow the adequate practice as compared to women who are illiterate or with primary education. Women with good knowledge scores are more likely to follow adequate practice during Covid-19 as compared to their counterparts (Table 5).

Discussion

The study was conducted in Karachi, Pakistan, to determine the predictors of good knowledge and adequate practices related to COVID-19 among women. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to investigate COVID-19 associated knowledge and practices among Pakistani women, and factors associated with it. COVID-19 is neither a water-borne disease nor is it an air-borne disease, but it transmits from one individual to another through respiratory droplets produced from coughing or sneezing and contaminated hands [11].

In the current study, almost half of the study participants had good knowledge about COVID-19. Educated women had higher knowledge score as compared to their counterparts. The educational status of women was a predictor of the knowledge score. The results of this were similar to the study conducted by Naser et al. [12]. Our study has also found that having at least one comorbidity is also a predictor of a good knowledge score. It is evident that people who are suffering from any other illness are more likely to adopt healthy behavior during a pandemic, and they take more precautionary measures in order to prevent themselves and others from the disease and its complications [5]. The knowledge score among women in the current study is low as compared to the study conducted in Saudi Arabia [9]. However, the study conducted in Pakistan also reported a low knowledge score among the general public [13]. Moreover, our research did not find any significant association between knowledge scores and certain demographic variables like age and occupation. In contrast to the results of our study, certain studies have found a significant relationship between age and occupation, and knowledge [14,15].

The current study has found that less than half of the study participants followed adequate practice, and these results are in contrast with the study conducted by Geldsetzer [15]. Some of the predictors significantly associated with adequate practice in the current study include educational status, past history of COVID-19, and good knowledge score related to COVID-19. Being educated is associated with a higher chance of adequate practice, and this finding is consistent with recently carried out studies [12,14]. Our results are more or less similar to those of a Malaysian study that also found good practices among the general Malaysian population toward COVID-19 [16]. Several explanations for the women’s good practices can be described, including the implementation of lockdown across the city. Because of the quick spread and hundreds of deaths across the world, there has already been a great deal of fear among the general public. COVID-19 news has been widely circulated in the media, and social media has also been quick to disseminate information. However, comparing to the past studies [9,15]. A fewer number of participants in the current study has adequate practice during the COVID-19 because of lack of knowledge and certain misconceptions about different aspects of the COVID-19.

Certain misconceptions were found in our study that is quite common among women including the use of garlic and turmeric and flu and pneumonia vaccines protect against this virus”. The Australian study reported that misconceptions and uncertainties related to COVID-19 were widespread among the general population [17]. This misinformation and misconceptions can create an obstacle towards the pathways of taking appropriate preventive measures and adopting positive behavior changes. Therefore, it is important to identify accurate and correct knowledge about the illness that is considered vital for risk reduction practices and behaviors.

The current study has shown that for the women to perform good practice during COVID-19 after getting information, they should believe that these practices are effective in preventing themselves and their family members from COVID -19. For instance, they should believe that washing hands and wearing masks would keep them protected against COVID-19, beyond merely being informed so, to perform the good practices and behavior. While information is at the heart of learning, given individual differences, a mismatch between information supplied and received is to be expected. It is important for public health professionals to believe that effective communication is vital that can be shaped by individual psychological and cognitive factors. The findings of our study have implied that emphasis needs to be put on boosting efficacy; therefore, programs related to COVID -19 may use messaging strategies that can stress the efficiency of target practices and behaviors promoted through these programs. It is also recommended that the program should prioritize populations who have poor efficacy beliefs, especially those who are less educated and have less knowledge about COVID-19.

Our study has certain limitations. Firstly, the research did not explore attitudinal factors associated with COVID-19 behaviors like perceived barriers or communication factors that may have impacted the women’s knowledge, including getting information from the media and processing of this information. Secondly, while effectiveness beliefs can encompass both response efficacy and self-efficacy, our study focused solely on the former, offering limited insights into the concept’s essentially composite nature. Thirdly, the study included only people who were there at the Liaquat National Hospital at the time of the survey. In the future, more studies need to be conducted included samples from the community, in order to get comprehensive ideas about the knowledge and practices of women related to COVID-19.

Conclusion

Overall, the majority of the women who participated in the study had poor knowledge and followed inadequate practice during the Covid-19 pandemic—predictors associated with good knowledge, including educational status, marital status, and presence of any comorbidity. Similarly, predictors of adequate practice among women in Karachi including educational status, history of Covid-19, and good knowledge score. Despite all of the precautions, it appears that the only way to defeat this highly infectious disease is for organized and continuous efforts to raise public awareness of the disease. Furthermore, when conducting daily responsibilities, workers should adhere to government-issued standard operating procedures.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

References

- COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at John Hopkins University & Medicine.

- Salman M, Mustafa ZU, Asif N, Zaidi HA, Hussain K, et al. (2020) Knowledge, attitude and preventive practices related to COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in two Pakistani university populations. Drugs Ther Perspect 9: 1-7.

- Jordan J, Yoeli E, Rand D (2020) Don’t get it or don’t spread it? Comparing self-interested versus prosocially framed COVID-19 prevention messaging. Sci Rep 11(1): 20222.

- Ahmad T, Haroon MB, Hui J (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and economic impact. Pak J Med Sci 36(COVID19-S4): 73-78.

- Barkat R, Rahim A, Jiwani A, Khan S, Ali S (2021) Effect of perceived risk of covid 19 on protective behavioral changes among adult population in pakistan: A web-based cross-sectional study. Archives of Community Medicine and Public Health 7(2): 055-059.

- Singh A, Purohit BM, Bhambal A, Saxena S, Singh A, et al. (2011) Knowledge, attitudes, and practice regarding infection control measures among dental students in Central India. J Dent Educ 75(3): 421-427.

- Mohamad E, Azlan AA (2020) COVID-19 and communication planning for health emergencies. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication 36(1).

- Depoux A, Martin S, Karafillakis E, Preet R, Wilder SA, et al. () The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreaks. J Travel Med 27(3): 31.

- Baig M, Jameel T, Alzahrani SH, Mirza AA, Gazzaz ZJ, et al. (2020) Predictors of misconceptions, knowledge, attitudes, and practices of COVID-19 pandemic among a sample of Saudi population. PloS one 15(12): e0243526.

- World Health Organization (2020) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: Myth busters.

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, et al. (2020) Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. The New England Journal of Medicine 382: 1199-1207.

- Naser AY, Dahmash EZ, Alwafi H, Alsairafi ZK, Al Rajeh AM, et al. (2020) Knowledge and practices towards COVID-19 during its outbreak: a multinational cross-sectional study. MedRxiv.

- Tariq S, Tariq S, Baig M, Saeed M (2020) Knowledge, Awareness, and Practices Regarding the Novel Coronavirus Among a Sample of a Pakistani Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 23: 1-6.

- Zhong BL, Luo W, Li HM, Zhang QQ, Liu XG, et al. (2020) Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci 16(10): 1745-1752.

- Geldsetzer P (2020) Knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus disease 2019 among the general public in the United States and the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional online survey. Ann Intern Med.

- Geldsetzer P (2020) Use of rapid online surveys to assess people's perceptions during infectious disease outbreaks: a cross-sectional survey on COVID-19. J Med Internet Res 22(4): 18790.

- Faasse K, Newby J (2020) Public perceptions of COVID-19 in Australia: perceived risk, knowledge, health-protective behaviors, and vaccine intentions. Front Psychol 11: 551004.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.