Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

A Development of Synthetic Chimeric Peptide Against Human Papillomavirus 16 L1, L2, E6 And E7 Peptides-Based Therapeutic Potential in A Murine Model of Cervical Cancer

*Corresponding author:Md Asad Khan, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Jamia Millia Islamia, India.

Received:December 14, 2022; Published:January 03, 2023

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2022.17.002397

Abstract

The human papillomavirus (HPV), which causes cervical cancer, is the fourth most frequent disease in women globally. Although there are HPV preventative vaccines available, they have no therapeutic benefits and do not treat pre-existing infections. The goal of this research is to create a cervical cancer therapeutic vaccination. The target antigens for epitope prediction were the E6 and E7 oncoproteins from HPV16. The best epitopes were chosen based on antigenicity, allergenicity, and toxicity. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) and helper T lymphocytes (HTL) epitopes were predicted. In our study, software predicted, multiple H-2Db restricted HPV16 cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) epitopes on a synthetic chimeric peptide, was used along with different immunopotentiating adjuvants such as heat-killed Mycobacterium w (Mw) cells. In vitro TC-1 tumour cells expressing HPV16 E6 and E7 were able to be destroyed by CTL through subcutaneous immunisation with H-2Db-restricted HPV16 peptide, and C57BL/6 mice were also protected from in vivo challenge with TC-1 cells. This chimeric peptide performed best in vitro when combined with a peptide mixture that included Mw as an adjuvant. Thus, this strategy may offer a possible peptide-based therapeutic candidate vaccination for the prevention of cervical cancer caused by HPV infection.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Peptide Mixture, HPV, Therapeutic vaccine, CTL response

Introduction

With over 0.6 million cases and 0.3 million fatalities per year, cervical cancer is the fourth most prevalent malignancy in women globally [1]. This condition is mostly caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is spread through sex contact [2]. According to scientific research, HPV16 and HPV18 combined cause around 70% of all cervical cancers [3], and HPV16 is the most carcinogenic of these high-risk groups [4]. The high-risk group includes types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68 [5]. The circular double-stranded DNA genome of the non-enveloped HPV virus is about 8 kb long [6]. A long control region (LCR), a late region (L1, L2), and an early region (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, and E7) make up the HPV genome [1].

The primary virus-transforming proteins in high-risk HPV are the E6 and E7 oncoproteins, which also contribute to cell proliferation, immortalization, and transformation in human epithelial cells [7]. Nowadays, there are three commercially available HPV prophylactic vaccines, but none of them show a therapeutic effect on existing HPV infection and related cancers [8,9]. Therefore, the creation of a potent therapeutic vaccination is essential given the high prevalence of HPV infections. Additionally because of their crucial involvement in tumour development, cellular transformation (degradation of p53 and pRB), and virus replication, HPV L1, L2, E6, and E7 proteins are excellent candidates for developing a therapeutic vaccine [10,11].

To date, a number of therapeutic vaccines have been created using viral oncoproteins as the ideal target, including live vectorbased vaccines, vaccines based on bacterial or viral vectors, vaccines based on DNA and RNA vectors, vaccines based on peptides and proteins, and vaccines based on whole cells. However, according to [12], each technique has certain benefits and drawbacks. Finding efficient and secure ways for designing therapeutic vaccines is therefore crucial (e.g., increasing their immunogenicity) [13- 15]. Peptide vaccines were regarded as a significant strategy among numerous methods due to a number of benefits including high selectivity and sensitivity, simple manufacture, and cost effectiveness. Immunodominant T- and B-cell epitopes that inhibit immune responses against self-antigens should make up a good peptide vaccine (i.e., autoimmunity). The interaction of epitopes with the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is thus a crucial step [16].

In this study, MHC class I-binding and CTL-inducing epitopes on HPV16 E6, E7, L1, and L2 proteins have been identified, using algorithmic prediction software (CTLpred). The epitopes which overlap with the experimentally proved immunodominant epitopes, each from L1, L2, E6, and E7 regions of HPV16 were combined to construct a synthetic chimeric peptide (48 mer), having multiple epitopes recognized by CTLs. Adjuvants such as heat-killed cells Mw (Mycobacterial proteins), was used to determine whether delivery of chimeric CTL peptide along with these adjuvants could elicit immune responses against HPV16-associated tumors in a murine model. Peptide mixtures (L1, L2, E6, and E7) are generally phagocytosed and transported by APCs into draining lymph nodes, and use of adjuvant Mw allows sustained release of peptides over a period of days or even weeks. We have shown that immunization with an H-2Db -restricted epitope present on HPV16 chimeric CTL peptide, along with adjuvants Mw, generated peptide-specific cellular immune response, along with in vivo antitumor efficacy against HPV16 E6- and E7- expressing TC-1 cells, in C57BL/6 mice.

Material and Methods

In silico design of the HPV16 chimeric peptide HPV16 L1165- 173(9mer), L2108-120(13mer), E648-57(10mer), and E748-57(10mer) peptides were designed by algorithmic prediction software, CTLpred (by at: http://www. imtech.res.in/raghava), each having one CTL epitope. This server predicts specific epitopes by using neural network along with physiochemical properties of the epitopes [13]. The small peptides (9-13 mer) were combined with two glycine linkers to form a single large chimeric peptide {E648- 57}GG{E748-57} GG{L1165-173}GG{L2108-120} (48 mer), E6-E7-L1-L2 containing multiple CTL epitopes. Conformation of this chimeric peptide was analyzed on PyMOL software. This peptide was synthesized commercially from Genscript Corporation, USA (purity [95 % by HPLC), dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored at -70oC, until use.

Adjuvants

We were tested the adjuvants Heat-killed Mycobacterium w (Mw) cells at a concentration of 0.5 x 107 cells per mouse. Peptide (200μg, 50μg of each peptide L1, L2. E6 & E7)) was adsorbed on 500μg Alhydrogel 2% (Brenntag Biosector, Denmark) by mixing for 1h at room temorature and stored at 4oC.

Mice and Cell Lines

Female C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice (6-8 weeks old) were immunized subcutaneously (S.C.) with the chimeric peptide (200 μg in 100 μl PBS per mouse) along with adjuvant (killed Mw cells). Control mice received the same volume of PBS & Mw. Mice were boosted twice at an interval of 10 days in each group. Animals were killed 7-10 days after the last booster; splenocytes harvested and cultured for in vitro experiments. Tumor cell line TC-1 (generated by retroviral transduction of lung fibroblasts of C57BL/6 origin by HPV16 E6/E7 and c-Hras oncogene) was obtained from ATCC (USA). These cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10 % (v/v) fetal calf serum, 2 mM non-essential amino acid, and G418 (0.4 mg ml-1) at 37oC in 5 % CO2.

In Vivo Tumor Regression Assay

In vivo tumor regression was performed by injecting viable TC-1 cells (1 x 105 cells in 100 μl PBS per mouse) S.C., into the left flank of C57BL/6 mice, on day one. The peptide (200 μg per mouse) along with adjuvant (killed Mw cells/Alum/PLGA microspheres) was injected S.C, on day 8, followed by two boosters on days 18 and 28. Tumor size was assessed every 3-4 days for 35 days using calipers, once palpable tumors appeared (7-10 days post-TC-1 inoculation). Mice were sacrificed when tumor volume exceeded 2,000 mm3.

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbant Assay

ELISA was carried out on flat bottom polystryrene modules as described previously [17]. To determine the peptide specific antibody level in immunized mice, 0.5μg antigens of pure peptide cocktail (containing L1, L2, E6 & E7) were diluted in carbonatebicarbonate buffer (0.05 M, pH 9.6) and used to coat 100μl in 96-well plates for 16 h at 4оC. After washing with TBS-T (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 containing 0.05% Tween-20) and unoccupied sites were blocked with 150 μl of 5% fat free milk in TBS (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) for 4-6 h at 37°C., serum samples (diluted from 1:100) were added in triplicate, and the plates were incubated at 37оC for 1 h. The plates were washed four times with TBS-T. Bound antibodies were assayed with goat antimouse IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (diluted 1:2,000; Invitrogen) was added, and the plates were incubated at 37оC for 1 h. After a final wash, enzyme substrate TMB (Sigma) was added for color development, and immunoreactivity was detected by measuring absorbance at 450 nm using an ELISA plate reader (Biotek).

Lymphocyte Proliferation Assay

Lymphocyte proliferation post-in vitro stimulation by chimeric

peptide (10μg per well) was determined as described previously

[18]. Briefly, 100μl aliquots of splenocytes (5 x 105 cells per well)

was cultured in RPMI-1640 containing 10 % (v/v) FCS, 10 Uml-1

recombinant-mouseIL-2, and 0.05 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, in 96-

well plates. Cell Titer 96 AQueous One Solution Assay (Promega

Corp. USA) was used to measure proliferation of lymphocytes from

different groups. The percentage cytotoxicity was calculated as.

%Cytotoxicity = Experimental- Effector Spontaneous – Target

Spontaneous/Target Maximum – Target Spontaneous x 100

Cytolytic Activity Against TC-1 Tumor Cells

Effector-mediated cytolysis of TC-1 cell was measured by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay as has been described previously [18], using CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive assay kit (Promega Corp. USA).

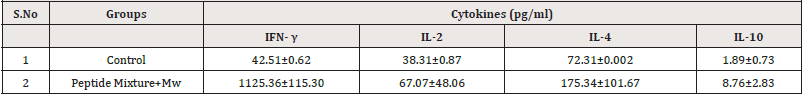

Estimation of Cytokines

Splenocytes from control and immunized groups were cultured with or without addition of chimeric peptide (10 μg per well), in 96-well plates, as for lymphocyte proliferation assay. Supernatants were collected after 48 h, for cytokine assay. Cytokine levels were determined using Endogen mouse IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-10, and IL-4 ELISA kits (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc. USA).

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Wilcoxon signed rank test were used for statistical analysis. Tumor regression percentage was analyzed by applying generalized estimating equation (GEE) population-averaged model. P values of B0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Chimeric Peptide Showed Regression of Tumors Against Post-TC-1

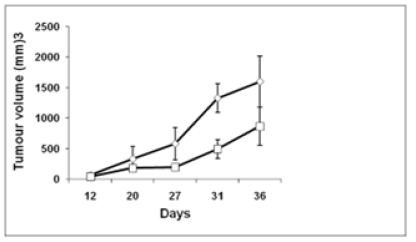

To assess whether the chimeric peptide was capable of causing regression of E7-related tumors, TC-1 cell line was injected s.c., on day 1, for tumor challenge assay. Tumor development was observed on the 7th day onward. Chimeric peptide along with Mw cells was injected, post-tumor challenge, for assessing tumor regression. We found TC-1 cell line showed tumor progration 1596.44 mm3 but peptide mixture with Mw showed 868.14 mm3. This was found to be significantly higher tumor regression as compared to controls, being 45.62 % for peptide mixture with Mw cells (Figure 1). To summarize, chimeric peptide developed in this study exhibited the trend with regard to antitumor efficacy: peptide mixture with Mw.

Figure 1:Tumor challenge and in vivo tumor growth with TC-1 tumor cells. Mean tumor volume ± SD (mm3) from mice (n = 6) immunized with chimeric peptide with Mw adjuvants is compared to respective control mice (injected with PBS along with adjuvant), on the indicated days, following tumor challenge. Tumor growth was monitored, using calipers, and average tumor volume was calculated, for each group: chimeric peptide with Mw. TC-1 control is a control group which received the same volume of PBS along with Mw adjuvant post-tumor inoculation. P values were calculated (*P<0.05).

Antibody Responses by Subcutaneous Immunization of Hpv 16 Peptides (L1, L2, E6 & E7) Cocktail with Immunoadjuvant Heat Killed Mw Cells

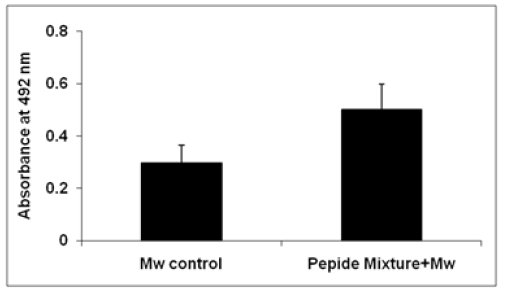

Subcutaneous immunization of peptide cocktail with heat killed Mw cells was found to induce in sera, the antibodies capable of binding to HPV-16 peptides mixture (L1, L2, E6 and E7) with Mw. Serum was taken on day 27 after the first immunization. Peptidesspecific antibody in serum IgG showed higher in compared to control heat killed Mw cells mice. The serum IgG level of peptide cocktail with Mw showed signigicantly higher in comparison to IgG level of Mw (Figure 2).

Figure 2:ELISA for serum IgG level of Mw and Peptide cocktail with Mw. Microtitre wells were coated with the respective antigens.

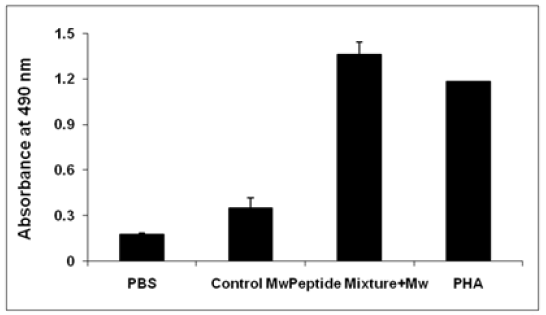

Chimeric Peptide Induced Lymphocyte Proliferation for Peptide Mixture with Adjuvant

In vivo primed splenocytes, when in vitro stimulated with chimeric peptide, exhibited a statistically significant (P B 0.05; Mann-Whitney U test) high level of proliferation as compared to control. Lymphocyte proliferat response, as measured in terms of mean OD490 value by MTT assay, showed 1.36±0.52, 0.35±0.02, and 0.178±0.01 mean stimulation indices (SI) ± SEM with peptide mixture with Mw, control Mw and PBS, respectively (Figure 3). Proliferation level was found to be significant (P B 0.05; Mann- Whitney U test or Wilcoxon signed rank test), when paired analysis (i.e., unstimulated vs. stimulated lymphocytes from immunized group) was performed.

Figure 3:In vitro lymphote proliferative response and antigen-induced CTL generation in C57BL/6 mice immunized with chimeric peptide. a Proliferation of lymphocytes was determined by MTT assay. Data are reported as mean stimulation index ± SEM, on restimulation with cognate antigen for 72 h in peptide along with Mw immunized groups. SI stimulation index (mean OD490 value from stimulated wells from immunized group/ mean OD490 value from unstimulated wells from control group).

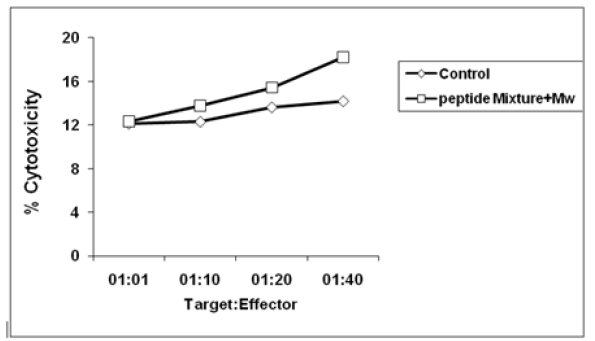

Cytotoxicity for Peptide Mixture Againt Tc-1 Cells

Viable effector cells from peptide mixture immunized and control groups were assessed for cytotoxic activity, against TC-1 cells, on in vitro stimulation. As shown in Fig. difference in percentage cytotoxicity due to effector cell-mediated lysis of TC-1 cells was 28.83% with peptide mixture, being significantly higher than in unstimulated effector cells from control groups at 1:40; target:effector ratio (Figure 4).

Figure 4:In vitro CTL cytotoxicity of TC-1 tumor cells was measured, by LDH estimation. CTLs were determined 7 days after the last booster. Pooled effector splenocytes of mice immunized with peptide misture with Mw and control group (n = 5 in each group), were co-cultured with target TC-1 cells, and cytolysis of the latter was determined. Data are expressed as mean ± SE of three separate experiments. (*P<0.05; Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Chimeric Peptide Showed Th-1 Type Response by Estimation of Cytokines

Stimulated splenocytes showed higher levels of interferon gamma (IFN- γ), moderate levels of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interleukin-10 (IL-10), and low level of interleukin-4 (IL-4) as compared to control. A significantly higher level of IFN-γ secretion was observed in immunized groups. A significant high secretion of IL-2 was seen with Mw. Among the Th-2 subtype, significant levels of IL-10 and IL-4 were significantly detected in culture supernatant in peptide mixture, Mw was used as adjuvant (Table 1). Data are expressed as mean ± SE in pg/ml for n= 5 mice. P values were calculated by comparing cytokine levels for control to immunized groups by Mann-Whitney U test. P<0.05 was considered as significant.

Discussion

HPV-related cervical cancer is a public health emergency in both developing and industrialised nations [19]. Although HPV prophylactic vaccinations are readily available, creating a therapeutic vaccine for cervical cancer still remains a crucial public health need 26. Researchers from all across the world have become interested in a novel method for creating new vaccines that combines immunogenicity, immunogenicity, and bioinformatics [20]. An appealing method to activate the immune system against cancer-associated HPV high-risk varieties is therapeutic vaccination. Targeting HPV antigens that can be constitutively expressed in HPV-associated cancers is important for a therapeutic vaccination [21] They are the perfect targets for developing a therapeutic vaccination due to the roles that HPV L1, L2, E6, and E7 play in the aetiology of tumours, cellular transformation, and virus replication [22,23] The production of peptide vaccines is simple, safe, and limited to one particular major histocompatibility complex (MHC).

In this study, we first identified specific immunogenic epitopes of HPV16 antigens by software, which overlapped with murine (H-2Db) CTL immunodominant epitopes for L1165-173 [24], L2108-120, E648-57 [25], and E749-57 [26]. We have designed a large chimeric peptide as a single entity, having these multiple epitopes, thus facilitating antigen uptake and coordinating antigen presenting cell activation as well as antigen presentation. We also investigated the effect of adjuvants/delivery systems for this peptide antigen. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes epitopes present in L1 and L2 capsid protein sequences are known to generate very weak responses as compared to E6 and E7 proteins. Powerful paradigms have hence been designed to choose peptides from the E6 and E7 oncoproteins to develop peptide-based antitumor vaccines [27-29]. The induction of CTLs as well as antibodies, by peptide immunogen, can be further enhanced by use of novel adjuvants and delivery systems.

One study established the immunogenic potential of Q19D and Q15L peptides, from HPV16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins (E643-57 and E744-62 respectively), using Freund’s complete adjuvant in mice [30] In our study, we observed that s.c. vaccination with an H-2Db -restricted HPV16 chimeric peptide, along with adjuvants Mw, generated peptide-specific CTL-mediated cytolysis of HPV16 E6- and E7-expressing TC-1 tumor cells in vitro and protected against a subsequent in vivo challenge by TC-1 cells, in C57BL/6 mice. This peptide efficiently generated CTLs with the adjuvant tested Mw, which showed good efficacy. Moreover, stimulated splenocytes induced peptide-specific lymphocyte proliferation but to different extents with these adjuvants. Stimulated splenocytes showed higher levels of IFN-γ, moderate levels of IL-2, IL-4, and low levels of IL-10 in culture supernatant, thus exhibiting bias toward Th-1 type response, which in turn is known to play a major role in cure and prevention of cervical cancer.

However, when tested in vivo, chimeric peptide showed comparable antitumor efficacy with adjuvant Mw. A possible reason for this may be the continuous struggle, which exists between the tumor cells and the immune system, during the process of malignant transformation, with the tumor developing several mechanisms to escape immunosurveillance, especially if persistent [31] Therefore, the future of peptide vaccines may tend toward the use of long overlapping peptides as these may broaden the range of antigenic epitopes and limit the obstacle of MHC restriction. Overlapping peptides have proven to be effective in generating antigen-specific T-cell immune responses, in preclinical animal models [32,33] as well as in human clinical trials [34,35].

Conclusion

Millions of people throughout the world have been affected by cervical cancer, which is brought on by HPV. For the time being, there is no effective therapeutic vaccine for HPV infections. In this study, we tried to develop a multiepitope cervical cancer vaccine. We have generated a peptide-based candidate vaccine for HPV16- associated infection and tumors, which is capable of generating significant antigen-specific therapeutic effects, in a murine model of cervical cancer. Our preclinical observations can thus serve as an important foundation for translation into future clinical studies.

Conflict of Interest

No

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of J. N. Medical College and Hospital, AlMU, Aligarh, Utter Pradesh, India.

References

- Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, de Sanjosé S, Saraiya M, et al. (2020) Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: A worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health 8(2): e191-e203.

- De Sanjose S, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Clifford G, Bruni L, et al. (2007) Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: A meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 7(7): 453-459.

- de Villiers EM (1989) Heterogeneity of the human papillomavirus group J Virol 63(11): 4898-4903.

- Mirabello L, Clarke MA, Nelson CW, Dean M, Wentzensen N, et al. (2018) Te intersection of HPV epidemiology, genomics, and mechanistic studies of HPV-mediated carcinogenesis. Viruses 10(2): 80.

- Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, et al. (2009) A review of human carcinogens-Part B: Biological agents. Lancet Oncol 10 (4): 321-322.

- Doorbar J, Quint W, Banks L, Bravo IG, Stoler M, et al. (2012) Te biology and life cycle of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine 30(5): F55-F70.

- Munkhdelger J, Kim G, Hye young WHY, Dongsup Lee D, Sunghyun Kim F, et al. (2014) Performance of HPV E6/E7 mRNA RT-qPCR for screening and diagnosis of cervical cancer with TinPrep® Pap test samples. Exp Mol Pathol 97(2): 279-284.

- Bharadwaj M, Hussain S, Nasare V, Das BC (2009) HPV & HPV vaccination: issues in developing countries. Indian J Med Res 130(3): 327-333.

- Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen OE, Bouchard C, Mao C, et al. (2015) A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med 372(8): 711-723.

- Hoppe Seyler K, Bossler F, Braun JA, Herrmann AL, HoppeSeyler F, et al. (2018) The HPV E6/E7 oncogenes: key factors for viral carcinogenesis and therapeutic targets. Trends Microbiol 26(2): 158-168.

- Ganguly N (2012) Human papillomavirus-16 E5 protein: oncogenic role and therapeutic value. Cell Oncol 35(2): 67-76.

- Yang A, Farmer E, Wu TC, Hung CF (2016) Perspectives for therapeutic HPV vaccine development. J Biomed Sci 23(1): 75.

- Gomez Gutierrez JG, Elpek KG, Montes de Oca LR, Shirwan H, Zhou HS, et al. (2007) Vaccination with an adenoviral vector expressing calreticulin-human papillomavirus 16 E7 fusion protein eradicates E7 expressing established tumors in mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother 56(7): 997-1007.

- Cassetti MC, McElhiney SP, Shahabi V, Pullen JK, Poole ICL, et al. (2004) Antitumor efficacy of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon particles encoding mutated HPV16 E6 and E7 genes. Vaccine 22(3-4): 520-527.

- Reinis M, Stepanek I, Simova J, Bieblova J, Pribylova H, et al. (2010) Induction of protective immunity against MHC class I-deficient, HPV16- associated tumours with peptide and dendritic cell-based vaccines. Int J Onco 36(3): 545-551.

- Li W, Joshi MD, Singhania S, Ramsey KH, Murthy AK, et al. (2014) Peptide vaccine: progress and challenges. Vaccines 2(3): 515–536.

- Md Asad Khana, Khursheed Alamc, Syed Hassan M, M Moshahid A Rizvi (2017) Genotoxic effect and antigen binding characteristics of SLE auto-antibodies to peroxynitrite-modified human DNA. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 635: 8-16.

- Sharma C, Dey B, Wahiduzzaman M, Singh N (2012) Human papillomavirus 16 L1-E7 chimeric virus like particles show prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy in murine model of cervical cancer. Vaccine 30(36): 5417-5424.

- Vu M, Yu J, Awolude OA, Chuang L (2018) Cervical cancer worldwide. Curr. Probl. Cancer 42(5): 457-465.

- Mora M, Veggi D, Santini L, Pizza M, Rappuoli R (2003) Reverse vaccinology. Drug Discov 8(10): 459-464.

- Schiller JT, Castellsague X, Villa LL, Hildesheim A (2008) An update of prophylactic human papillomavirus L1 virus-like particle vaccine clinical trial results. Vaccine 26(Suppl 10): K53-K61.

- Kumar A, Yadav IS, Hussain S, Das BC, Bharadwaj M (2015) Identification of immunotherapeutic epitope of E5 protein of human papillomavirus-16: An in silico approach. Biologicals 43(5): 344-348.

- Chabeda A, Yanez RJR, Lamprecht R, Meyers AE, Rybicki EP, et al. (2018) Therapeutic vaccines for high-risk HPV-associated diseases. Papillomavirus Res 5(6): 46-58.

- Ohlschlager P, Osen W, Dell K, Faath S, Garcea RL, et al. (2003) Human papillomavirus type 16 L1 capsomeres induce L1- specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and tumor regression in C57BL/ 6 mice J Virol 77(8): 4635-4645.

- Peng S, Ji H, Trimble C, He L, Tsai YC, et al. (2004) Development of a DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus type 16 oncoprotein E6. J Virol 78(16): 8468-8476.

- Feltkamp MC, Smits HL, Vierboom MP, Minnaar RP, de Jongh BM, et al. (1993) Vaccination with cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope-containing peptide protects against a tumor induced by human papillomavirus type 16-transformed cells. Eur J Immunol 23(9): 2242–2249.

- Zwaveling S, Ferreira Mota SC, Nouta J, Johnson M, Lipford GB, et al. (2002) Established human papillomavirus type 16-expressing tumors are effectively eradicated following vaccination with long peptides. J Immunol 169(1): 350-358.

- Gao L, Chain B, Sinclair C, Crawford L, Zhou J, et al. (1994) Immune response to human papillomavirus type 16 E6 gene in a live vaccinia vector. J Gen Virol 75(Pt 1): 157-164.

- Ressing ME, Sette A, Brandt RM, Ruppert J, Wentworth PA, et al. (1995) Human CTL epitopes encoded by human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 identified through in vivo and in vitro immunogenicity studies of HLA-A*0201-binding peptides. J Immunol 154(11): 5934-5943.

- Sarkar AK, Tortolero Luna G, Nehete PN, Arlinghaus RB, Mitchell MF, et al. (1995) Studies on in vivo induction of cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses by synthetic peptides from E6 and E7 oncoproteins of human papillomavirus type 16. Viral Immunol 8(3): 165-174.

- Piersma SJ (2011) Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in cervical cancer patients. Cancer Microenviron 4(3): 361-375.

- Vambutas A, DeVoti J, Nouri M, Drijfhout JW, Lipford GB, et al. (2005) Therapeutic vaccination with papillomavirus E6 and E7 long peptides results in the control of both established virus-induced lesions and latently infected sites in a pre-clinical cottontail rabbit papillomavirus model. Vaccine 23(45): 5271-5280.

- Tarpey I, Stacey SN, McIndoe A, Davies DH (1996) Priming in vivo and quantification in vitro of class I MHC-restricted cytotoxic T cells to human papilloma virus type 11 early proteins (E6 and E7) using immunostimulating complexes (ISCOMs). Vaccine 14(3): 230-236.

- Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, Lowik MJ, Berends van der MDM, et al. (2008) Phase I immunotherapeutic trial with long peptides spanning the E6 and E7 sequences of high-risk human papillomavirus 16 in end-stage cervical cancer patients shows low toxicity and robust immunogenicity. Clin Cancer Res 14(1): 169-177.

- Welters MJ, Kenter GG, Piersma SJ, Vloon AP, Lowik MJ, et al. (2008) Berends-van der Meer DM et al. Induction of tumor-specific CD4? and CD8? T-cell immunity in cervical cancer patients by a human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 long peptides vaccine. Clin Cancer Res 14(1): 178-187.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.