Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Women Veterans Reintegrating into Civilian Life

*Corresponding author: Kristelina Gonzalez, PsyD., The Chicago School of Professional Psyhology - Anaheim, CA, USA.

Received: July 17, 2023; Published: July 20, 2023

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2023.19.002614

Abstract

Women are representing a larger proportion of the military population than ever before. Thus, women are experiencing the effects of being in combat zones. Fifty-seven percent of discharged service women report moderate to high levels of combat exposure and traumatic experiences. [1] A major issue in returning from deployment is reintegrating into civilian life. This was an exploratory study to determine difficulties in reintegration for women veterans and servicewoman. It was found that women who served in combat, contrasted with those who did not, did not report any greater use of drugs nor problems reintegrating to civilian life, nor score higher on PTSD. Thus, serving in a combat zone did not create unique problems for these women. They did report one specific difference: being bothered by memories. This finding lends credibility to the results, as it makes sense that those women who served in a combat zone would have more significant negative memories than those women who did not serve in a combat zone. In general, the married veterans reported the least problems with reintegrating to civilian life. Thus, having that kind of support was very helpful. However, for those veterans who felt they needed psychological help after serving, the biggest problem was in relating to their spouse. Thus, these results reflect the importance of having a strong source of support when one leaves the military and returns to civilian life. Finally, these results show that these women veterans could handle their combat experience.

Keywords: reintegration, women veterans, PTSD, substance abuse, military culture

Introduction

More than 2.2 million U.S. service members have been deployed to Afghanistan or Iraq war zones as part of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF). Increasing numbers of women serve in the military, and they are now preforming roles very similar to those of male service members. Currently, women represent a larger proportion of U.S. military forces than ever before, comprising approximately 14% of forces deployed in support of OEF/OIF, representing over 180,000 deployed female troops. [2] Street, et al., stated the rates of exposure for women are low - findings suggest that women still experience substantial amounts of combat exposure even if the categorization would be low amounts of exposure. Furthermore, they reported that among women who self-reported levels of exposure in combat areas, 3% were classified as having had high levels of combat exposure, and 12% of women were classified as experiencing moderate levels of combat exposure. According to Street, Dawne & Dutra (2009), comparable rates were reported for male service members, which suggest that women had “substantial exposure to circumstances of combat,” and highlight the importance of attending to women’s experiences of combat within the OEF/OIF group [2,3].

Many servicewomen returning from deployment are still in active service in addition to women veterans who had been exposed to stressful and traumatic experiences, such as combat. Fifty-seven percent of servicewomen who report having had moderate to high levels of combat exposure and traumatic experiences have been discharged from the military and thus have achieved veteran status. [1] Research on the impact of stressors on female veterans’ physical and mental health are ongoing, and therefore, healthcare providers for veterans are concerned with the serious physical and mental health issues facing female military veterans. Between 2005 and 2015, the number of women veterans using Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system services increased 46.4%, from 237,952 to 455, 875. [4] This means that women seeking services from the VA have doubled since the inception of OEF/OIF. The VA is organizing the current research and evaluation of OIF/OEF veteran healthcare needs, services, costs, and care utilization in order to address the needs of this growing population.

A major issue for servicewomen returning from deployment is reintegrating into civilian life. There are several factors that women veterans face during reintegration. Some of the problems are substance use, depression, anxiety, sexual trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), homelessness, and isolation. Recently, research indicated women veterans are carrying a heavy burden post deployment [5]. Carney and colleagues reported that 25 percent of these women had children and were more likely to be single (divorced, separated, or never married) than their male counterparts. [5] Additionally, it was reported that over 30 percent of women veterans from the Vietnam era and their younger cohorts struggle with economic difficulties and inequality. [6] It is believed that women veterans “are more likely than male veterans to be homeless, divorced, or raising children as single parents.”. [7] Kasinof also stated that women veterans under fifty are more than twice as likely as their male counterparts to take their own lives. [7] Understanding the underpinnings of women veterans reintegrating from military into civilian life is not yet fully understood. [6,8,9] Based on the conclusions of Street, et al., and it appears that women veterans’ mental health and life problems are not being treated with the same respect and resources as are those of male veterans. [2,7] There is an abundance of information comparing women to men in other mental health aspects, but not in the reintegration process and its effects on the family. [10] Furthermore, focusing on women who also sacrificed their lives, their family relationships, and especially their relationships with their children to be heroes to their country should be assisted and guided with as much respect and dignity as their male counterparts.

Health care needs among female service members and veterans have often been unmet and misunderstood by providers working within military-supported settings, such as Department of Defense (DoD) and Department of Veteran Affairs. [11] Meeting and addressing the supportive needs of female veterans is important for several reasons. Female veterans are more likely than their male counterparts to report mental health concerns such as posttraumatic stress, depression, and suicidal thoughts. [11,12] Research suggests women are also more likely than men to screen positive for depression both before and after deployments and to use mental health services at higher rates. [11,13] When leaving the military, the separation from the military can be a tough time for men and women alike. It is believed that post separation from the military, rates of interpersonal conflict, and behavioural health symptoms are highest within the first 6 months. [11] It is vital to understand the foundation of addressing mental health needs and its role in the wellbeing of our women veterans.

One of the most prevalent disorders in women veterans is PTSD. [4] There are different etiological factors that can play a role in how one is affected by PTSD. The Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) has several criteria to assist in understanding and treating PTSD sequela. For example, military culture alone can be a traumatic experience. Demers reported different phases on how the military will introduce their own culture and strip away any sense of individuality. [12] Demers further elaborates how military indoctrination is where civilians are transformed into a collective group, which shares a distinctive identity. Recruits are trained to “never abandon their fellow warriors in combat and never show weakness to fellow warriors or to the enemy.” [12,14] Such collective values are generally referred to as the Military Culture.

Abiding by these values can be very difficult for an individual regardless of gender. Diagnosing a service member or veteran with PTSD does not necessarily derive simply from combat experience, but perhaps to military culture, level of assimilation, coping abilities, social support, and other factors. [4,9,14] The prevalence of returning veterans with PTSD and other mental health and life issues are of such high number that it is important to study in depth the problems these women veterans are experiencing in order to identify solutions and to best mitigate their effects.

As a decade of war in Iraq and Afghanistan officially ended, there are service members who served in war zones who are suffering from mental health problems sustained during the combat. One study estimated that 19 percent of individuals returning from OIF and 11 percent of those returning from OEF have mental health problems. [9] Consequently, service members who are struggling with physical and psychological injuries are seeking a remedy and looking for a rapid approach to numb the invisible psychological wounds. Several factors might exacerbate the impact of trauma, such as substances (e.g., illegal/legal), on women veterans’ mental health. It appears that many women veterans are in need of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment. In analyses of data from the National Survey of Women Veterans, the prevalence of alcohol misuse was 27% among women veterans. [1] Similarly, Carlson, Stromwall & Lietz reported that following deployment, about 30 percent of active duty and National Guard or Reservist women were binge drinkers, and 7.4 percent to 10 percent were heavy weekly drinkers, and 4.4 percent to 5.5 percent reported at least one drinking- related problem [9].

Significant comorbidity has been found in female veterans, thus making it crucial to also screen for substance use disorders. Co-occurring mental disorders among veterans returning from OEF/OIF, especially PTSD in conjunction with other disorders, were noted to be a serious problem in a 2008 report commissioned by the U.S. military, which calls this a “cascade of negative outcomes.” [9] As the number of deployments for women increase, so are levels of stress and depression. Use of substances may appear subtle in the beginning, as a way to cope with the demands of military experience. The use of drugs and alcohol have a way to numb or decrease the effects of having been in war zones. At times, substances can create a mental gain, so as to reduce suffering of other pains, such as physical or mental. As the use of substances continues, dependency on substances becomes more pronounced. Although treatment is available in the military, the “zero” tolerance policy for drugs and the stigma surrounding the idea of not being able to “handle” your psychological stress can be barriers in seeking help while enlisted or deployed [1].

Statement of the Problem

There is a great need for mental health assistance within the military, and the government continuously makes an effort to assist service members and veterans who are battling with “invisible wounds.” For example, the DoD spent $958 million on mental health treatment in 2012, roughly double the $468 million it spent in 2007. Military personnel make attempts to keep their service members physically safe and secure for any possible missions that may lay ahead. Similarly, mental health is equally important to any successful mission, and the safety of the unit. The DoD has attempted to bring awareness of mental health problems to active-duty service members and veterans alike. Ganz stated that the idea of being tough and not allowing oneself to show any signs of weakness, could affect a soldier far greater than toughing it out. Ganz documented that from the beginning of boot camp, one is engrained with concepts of courage, faithfulness, commitment, leadership, yet lacking the guidelines on how to seek appropriate help if needed (i.e. the Military Culture). [14] In addition, Ganz proposed that this standard could be a potential problem because when seeking assistance for substance use or PTSD, a service member or veteran might view seeking help as a weakness. [14] In addition, service members and veterans may fear that they will be punished for seeking help (shunned, criticized, rejected for promotion). Thus, the extent to which a service member identifies with the values of the Military Culture, might interfere with their ability to seek help.

Women’s transition from military to civilian status can be fraught with many challenges. Potential barriers to receiving professional help include mental health stigma and reluctance to use VA facilities. [9,14] Carlson, Stromwall & Lietz reported that women veterans have traditionally been underserved, and most female veterans do not receive their health care from the VA. [9] Similarly, among the many mental health problems that plague our women veterans, is PTSD. [4] This disorder, if not diagnosed correctly and treated properly, can cause an array of other issues for the women veterans. Substance abuse among U.S. military service members is an ongoing problem for the military and for veterans, especially women veterans [15].

At present, the majority of research on women veterans are problem biased and quantitative in nature. [12] However, there were few studies that focused on female veterans. Demers found that female veterans’ problems are understudied when compared with male veterans. For example, Demers reports that among all VA investigations funded through both public and private sources, only 2.6% of the research is conducted with female veteran participants. Thus, there is clearly a need to learn from the perspectives of women veterans what are the difficulties they face in reintegrating to their families and to civilian life.

The intent of this study was to explore and expand the current understanding of reintegration of women military members, especially how PTSD and drugs and alcohol play a role in the level of difficulty they experience in reintegrating. This study focused on these two problem areas as they appear to be two major areas of difficulty for women veterans. The present study focused solely on women service members who were deployed to a combat area and compare their experiences in reintegrating with those of women veterans who were not deployed to a combat area. A specific focus was on the relationship of the women veterans’ endorsement of the military culture to adjustment to reintegrating.

The study design is quantitative utilizing the Ganz Scale of Identification with Military Culture to assess the individual’s levels of identification with the values endorsed by the military culture. [14] The goal of this study is to highlight the difference exposure to combat areas has for women veteran’s reintegration to civilian life compared to those who did not have combat exposure. In regard to negative mental health outcomes, specifically PTSD and drug and alcohol use, it is believed that findings from this study may provide and promote changes in approaches targeted to military supporting organizations.

The Present Study

The purpose of this study was to understand and address reintegration of military members, specifically women veterans, and how PTSD and drugs and alcohol play a role in the level of difficulty in reintegrating. As stated earlier, men and women come into the military from diverse cultural backgrounds. The one thing they ultimately share is assimilation into the military culture. One of the primary goals of boot camp, the training ground for all military personnel, is to socialize recruits by stripping them of their civilian identity and replacing it with military identity (Demers, 2013; Ganz, 2017).[12,14] The study design was quantitative utilizing the Ganz Scale of Identification with Military Culture to assess the individual’s levels of identification with the values endorsed by the military culture. The goal was to highlight the effects of exposure to combat areas that have an influence on reintegration, possibly leading to negative mental health outcomes, specifically PTSD and drug and alcohol use. It was believed that findings from this study may provide an empirical basis to promote changes in approaches and/or content of psychoeducation that were targeted to military supporting organizations and the mental health professionals who helped provide services to them before leaving the service regarding reintegration as well as after leaving the service.

Null Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: There will not be a significant difference on the Military to Civilian Questionnaire (M2C-Q) in levels of reintegration between the women veterans who were in combat areas and those who were not.

Hypothesis 2: There will not be a significant difference on The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) in levels of drug misuse between women veterans in combat areas versus those who were not.

Hypothesis 3: There will not be a significant difference on The Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT) Questionnaire of PTSD symptoms between women veterans who were in combat areas and the women who were not.

Methods

Participants

The present study aimed to obtain completed surveys from women who were in combat areas and from women veterans who had not been deployed to combat areas. The participants must have met the following inclusion criteria to be included in the study. They must currently or have previously served in any branch of the US Military and had an experience reintegrating back into civilian life. Participants must have been at least 18 years of age and identified as being a woman. All veterans or active-duty members from any MOS, rank, or branch, with at least one-year time-in-service after completion of Initial Entry Training were also eligible to participate.

The participants were contacted via email through the researcher’s personal contacts. The BCC field was used when sending the email so that the email addresses could not be seen by those receiving the email. The email provided information on informed consent, screening questionnaire, and how to access the digital survey. At the conclusion of the study, participants received a debriefing message, which included resources for help with any mental health concerns. The informed consent included information on time requirements of the study, what participation entails, risks and benefits of participation, and instructions on where to seek additional information regarding in this research study. Participants acknowledged consent when they accessed the survey link and clicked the button that appeared at the end of the Informed Consent that stated: I Agree, and by completion of the survey and submitting it. The recruitment email asked the participants to recruit other participants by forwarding the recruitment email to other perspective participants, using a Snowball sampling technique. Participants also acknowledge consent to participate by completion of the survey.

Twenty-four participants completed all of the demographic information, but only 23 completed the entire survey. Demographic information indicated that 6 were in the age range of 25-34, 13 were between 35 – 44, 1 was in the age range of 45-54 and 3 were between 55-64. Seven of them had less than seven years of military service, 7 had 14-25 years of service, and 10 had more than 25 years of service. Six of them had some college education or less, 10 had AA degrees, seven had bachelor’s degrees, and 1 had a master’s degree. Eleven of the participants did not have any children, six had one child, 6 had two children and 1 had three children, The breakdown of number of children for each marital status is presented in Chart 1.

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire: The respondents were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire that would help to identify any limitations to the generalization of the findings from this study. The demographic questionnaire was confidential and did not collect any personally identifiable information. The demographic questionnaire asked for such information as branch of service, status of service (to ensure meeting the inclusion criterion), as well as other questions related to rank, age, gender, marital status, and combat experience. The demographic questionnaire also allowed respondents to indicate whether they have treated for mental health disorders previous to boot camp as well as since joining the service, and whether they think that they have problems associated with having served in the military.

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10): Was used in this study to measure potential misuse of drugs by women veterans. The DAST-10 was a 10-item self-report questionnaire that was designed to identify patterns of behavior that corresponded with the misuse and/or abuse of drugs, and the DAST was developed by Harvey A. Skinner, PhD at the Center for Addiction and Mental Health, located in Toronto, Canada. [16] The DAST-10 was a shortened version of the original DAST, which contained 28 items that were systematically constructed based on the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test [16,17].

Validity and reliability of the DAST-10 were psychometrically tested by Yudko, Lozhkina, and Fouts, and it was found to have an overall exceptional reliability and validity. [17] The DAST-10 was strongly correlated (r = .98) with the original DAST, and had an excellent internal consistency range of .86 to .94. [17] Because face validity of the DAST-10 was considered to be extremely high, the DAST was highly susceptible for faking good. [17] Therefore, it was crucial to keep the anonymity of each survey to in order to receive an honest response.

Military to Civilian Questionnaire (M2C-Q) Questionnaire: This questionnaire was a 16-item self-report measure of post deployment community reintegration difficulty. The selected M2C-Q items assessed difficulty in areas hypothesized as providing the basis for post deployment community reintegration: (a) interpersonal relationships with family, friends, and peers; (b) productivity at work, in school, or at home, (c) community participation; (d) selfcare; (e) leisure, and (f) perceived meaning in life. The 16 M2C-Q items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale with these response options: 0 = No difficulty, 1 = A little difficulty, 2 = Some difficulty, 3 = A lot of difficulty and 4 = Extreme difficulty. The internal consistency of the M2C-Q was .95. Factor analyses indicated a single total score was the best-fitting model.

The Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT) Questionnaire: Was an eight-item self-report measure that assessed the core symptoms of PTSD (intrusion, avoidance, numbing, arousal), somatic malaise, stress vulnerability, and role and social functional impairment. Symptoms were rated on fivepoint scales from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). [18] The SPRINT was responsive to symptom change over time and correlated with comparable PTSD symptom measures. The SPRINT demonstrated solid psychometric properties and served as a reliable, valid, and homogeneous measure of PTSD illness severity and of global improvement. The authors suggested a cutoff score of 14 for this screen and that those who screen positive should be assessed with a structured interview for PTSD.

Ganz Scale of Identification with the Military Culture (GIMC): This inventory was developed by Ganz based on her conceptualization of the military culture and designed to identify the extent to which the individual endorsed the various components of the U.S. Military Culture.[14] The Ganz scale consisted of eight statements that addressed eight core values from the different branches of military service. Each statement allowed the participant to identify their level of agreement with how each core value impacted their view or belief surrounding mental health, on a 7-point Likert scale from “Not at All” to “Very Much.” This was the third use of the GIMC; therefore, its reliability and validity were currently unknown [14,19].

Procedures

The participants accessed the study by going to the link indicated in the recruitment message. Upon accessing the study, they were sent to the screening questionnaire, and based on their eligibility they were then sent to the Informed Consent form. If they agreed to participate, they clicked on the I Agree button. Then they were asked to complete the Demographic form and 4 short questionnaires: 1. Military to Civilian Questionnaire (M2C-Q), 2. The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10), 3. Ganz Scale of Identification with the Military Culture (GIMC), and 4. The Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT) scale. The questionnaires took approximately 20 minutes to complete. After completing the last form, participants were directed to the debriefing statement page that includes further information about the study and information regarding mental health resources if the participant desired mental health services or resources after completing the questionnaires.

In addition, all information was de-identified, and confidentiality was maintained and did not impact future military involvement. Although participants were asked about their drug use and participating in illegal activity, all data retrieved only spoke to possible trends or patterns of drug use and/or illegal activity. No information was gathered about specific drug use or abuse from the participant. To ensure that confidentiality was maintained all information that was collected was kept on a password-protected computer to which only the researcher and the research Chairperson had access. The data gathered from all participants was collected by the researcher, deidentified, although no identifying information was requested, and recorded into an SPSS usable form (Excel spreadsheet). The confidentiality was maintained by using an assigned sequential identification number for each participant based on their survey start time. The data will be kept for 5 years, and then it will be destroyed. Also, respondents were notified that their voluntary participation in the research study would result in a $5.00 donation to the Foundation for Women Warriors for each completed survey as a gesture of appreciation for their participation.

Results

A total of 24 women veterans completed a major portion of the forms. However, only 23 completed all of the forms. Despite the small N, there were a number of significant effects found. Of central interest was whether the women veterans who experienced combat would report different levels of identification with the military culture (GIMC), misuse and/or abuse drugs (DAST-10), have greater problems with reintegration (M2C-Q) and traumatic stress (SPRINT). The findings will first be reported for Combat experience. In contrast to the almost completely non-existent effects of having been in a combat zone, significant differences in integrating to civilian life were found based on marital status, and significant effects were found for the women who reported needing psychological help after having served. However, it will be noted that the need for help due to service-related issues was not differential based on whether the woman veteran had experienced combat or not–that was irrelevant. In other words, combat experience (with one specific exception) did not create unique or greater problems for the women who experienced combat compared to the problems reported by all the women as being associated with military service. The results for marital status and for service-related issues will be reported second and third after the results for combat experience or not.

Effects of Experiencing Combat

Fourteen of the women veterans reported having been deployed to a combat zone, and nine reported that they had not. The only difference found between those who reported experiencing combat and those who had not was on the PTSD scale item of being troubled by memories (F (1, 21) = 4,443, p = .047). The women veterans who experienced combat had a higher score on this item (m = 1.43, sd = .938), than did the women veterans who did not experience combat (mean = ,60, sd = .960). Thus, other than this one specific reported effect from experiencing combat, these women veterans did not report having difficulties as a result of their combat experience. Therefore, null hypotheses 1, 2 and 3 cannot be rejected as combat experience did not result in higher scores on drug problems, PTSD nor with reintegration to civilian life.

Relationship of Marital Status to Difficulties Reintegrating

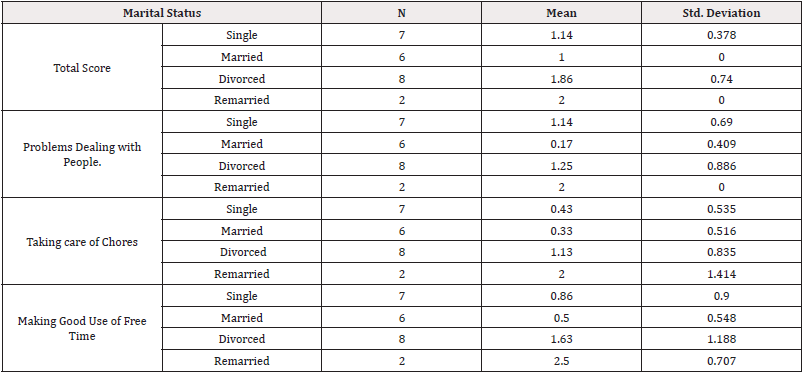

Relationship of Marital Status to Military to Civilian Questionnaire (M2C-Q): There was a significant effect of Marital Status on reintegration into civilian life (F (3, 19) = 3.326, p =.042) on Total Scores on the M2C-Q. The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. It can be seen in Table 1 that the married women veterans reported the least amount of difficulties on the M2C-Q items. In addition, there were significant differences of marital status on four of the items of the M2C-Q. There significant effects of Marital Status on Problems Dealing with People and reintegration (F (1, 19) = 4.005, p = .026), Taking Care of Chores (F (3, 19) = 3.353, p = .045), Making Good Use of Free Time (F (3, 19) = 3.425, p= .045. These means and standard deviations are also presented in Table 1. It should be noted that only 2 of the participants reported being remarried, and conclusions regarding the marital status of being remarried should not be considered to be reliable (Table 1).

Table 1: Mean and Standard Deviation for Significant Differences for Marital Status on M2C-Q Total Score and 3 items.

Relationship of Marital Status to PTSD Scores

There were also main effects of Marital Status on the PTSD Total score (F (3, 19) = 3.201, p =.047) and 5 of the individual items. The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 2. There were significant effects of marital status on Poor Sleep (F (3, 19) = 3.461, p = .041), Pain (F (3, 19) = 4.297, p = .021), Stress (F (3, 19) = 3.603, p = .037), Symptoms Interfere with Work (F (3, 19) = 4.712, p = .015), and I Feel Much Improved (F (3, 19) = 3.053, p = .059). Although “feel much improved” did not quite reach conventional levels of statistical significance, considering the size of the sample, it was determined that missing a possible significant effect (Type II error) was more consequential than a Type I error. As with the M2C-Q scale, it can be seen in Table 2 that the married women veterans generally reported the lowest levels of PTSD symptoms, and they reported a higher level of feeling improved more than the others (Table 2).

Table 2: Means and Standard Deviations for the effect of marital status on PTSD Total score and 5 individual items on the scale.

Need for Psychological Help for Service-Connected Problems Reported by the Servicewomen

Table 3: Means and Standard Deviations of Significant Differences on the M2C-Q for Women Veterans Who Reported that They Think They Need Psychological Help for Service-Related Problems.

Sixteen of the twenty-three women veterans reported that they believe they need psychological help for service-related problems. Those who reported that they think they need help with problems associated with having served in the military scored higher (F (1, 21) = 4.251, p = .052) on the Total M2C-Q scale score (m = 1.50) than did those women veterans who reported that they do not need psychological help for service related problems (m = 1.0). Again, although this difference did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance, the importance of not missing possible significant effects is considered to be most important, plus, there were a number of significant differences on several of the components of the M2C-2. This difference in Total score reflected the fact that they scored higher on 5 of the items on the M2C-Q measure. The means and standard deviations for the Total M2C-Q score and the 5 items that showed differences are presented in Table 3. The women who indicated that they think they help with service connected problems in reintegrating scored higher on: Dealing with People (F (1, 21)= 5.427, p =.030), Making New Friends (F (1, 21)= 8.869, p =.008), Keeping Up Friendships (F (1, 21)= 12.677, p =.002), Getting Along with Spouse (F (1, 21)= 5.938, p =.024), and Feeling Not Belonging as a Civilian (F (1, 21)= 5.203, p =.033). It can also be seen in Table 3 that the single biggest problem reported by these women veterans after serving is getting along with their spouse. It is also meaningful that they feel difficulty in feeling like they belong as a citizen, whereas the women veterans who report not needing psychological help for service-related problems hardly report any difficulty with “integrating” to civilian life (Table 3).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand and address reintegration of military members, specifically women veterans, and how PTSD and drugs and alcohol play a role in the level of difficulty in reintegrating. The primary goal was to highlight the effects of exposure to combat that may have an influence on reintegration, possibly leading to negative mental health outcomes, specifically PTSD and drug and alcohol use. A major goal of this study was to learn of problems experienced during reintegration by women veterans who are serving or who have served in the military to be able to promote changes in approaches and/or content of psychoeducation and support to the women veterans and to mental health professionals and military organizations.

Several significant findings emerged despite the small sample size for whom usable data was obtained. It was found that women who served in combat, in contrast to those who did not, did not report any greater use of drugs, problems reintegrating to civilian life, or scored higher on the SPRINT scale, except for one item. These findings suggest that serving in a combat zone did not create unique problems for these women. It is noteworthy that they did report one specific difference: How much have you been bothered by unwanted memories, nightmares, or reminders of the event? This finding lends credibility, as it makes sense that those women who served in a combat zone would have more significant negative memories that might trouble them than those women who did not serve in a combat zone.

However, it is not that these women veterans did not report problems reintegrated that they see as related to their military service experience. Thus, the well-established problems of discrimination, harassment and even sexual assault continue to take their toll (Kehle Forbes, et al., 2017). It was also found that, in general, the married veterans reported the least difficulty with reintegrating to civilian life. Although quality of marriage was not assessed formally in this study, it is reasonable to conclude that in general, the married servicewomen in this study found their marital status to be helpful. Thus, having a good, strong marriage - having that kind of support - was very helpful for these women veterans. However, for married veterans who felt they needed psychological help after serving, the biggest problem was in connecting to their spouse. Thus, when the marriage apparently was not strong, it was more vulnerable to the difficulties the women veterans experienced in reintegrating to civilian life. Thus, these results reflect the importance of having a strong source of support when one leaves the military and returns to civilian life. The specific ways in which marriage was helpful and the specific stresses when it was not helpful was not assessed in this study and is important to be identified in future studies.

Psychological Effects of Experiencing Combat

Readjustment experiences and subsequent problems have been identified by prior researchers as being comprised of mental health issues such as PTSD symptoms, suicidal ideation, as well as the perception of social support, all of which frame a veteran’s reintegration to life post deployment. [9,12] Reintegration refers to the ability to be an active functional member in one’s family, community, place of employment, and society. [8,14] These findings suggest that general measures of mental health problems may be insensitive to specific problems that stem from combat experience. Thus, using overall or total scores on a measure may miss highly specific negative effects that women veterans or service women may be experiencing. The difficult situations that service women or veterans frequently confront occur well after deployment and often manifest as PTSD symptoms.[12] For example, unwanted sexual advances, harassment, stress of different roles they play (military culture), and perhaps just being in the military could be stressful. In this study, the only difference found between women veterans who experienced combat and those who had not was on the PTSD scale item of being troubled by memories. The women veterans and servicewomen who experienced combat had a higher score than did the women veterans and servicewomen who did not experience combat regarding being bothered by memories. Thus, other than this one specific reported effect of experiencing combat, these women did not report having difficulties as a result of their combat experience. It is possible that this finding was due to women underreporting their symptoms due to possible stigma and worry. The time in between deployment and leaving the service could be causing memory bias, where they may not remember the severity of their symptoms. Possible minimization of symptoms or acknowledgement of PTSD symptoms could be hindering their ability to identify their experiences as PTSD. For example, as stated earlier, women often play many roles, and it is possible they may be mischaracterizing their PTSD symptoms for anxiety, stress, or life pressure.

Relationship of Marital Status to Difficulties Reintegrating

Relationship of Marital Status to M2C-Q: Women who stated they were married reported the least amount of difficulties on the M2C-Q items. This suggests that along with a good support system, women who can find comfort in speaking and sharing possible stressors with their significant other was also beneficial to the level of reintegration they had experienced. It is possible that having a support system in place prior, during and after deployment was beneficial physically, emotionally, and psychologically. This finding is consistent with research that proposes that the supportive needs of female veterans is important for several reasons. Female veterans are more likely than their male counterparts to report mental health concerns such as posttraumatic stress, depression, and suicidal thoughts. [8,12] Research suggests women are also more likely than men to screen positive for depression both before and after deployments and to use mental health services at higher rates. [11,13] Although research may suggest women are more likely to utilize resources at higher rates, it is not fully understood how protective factors may or may not decrease these rates. In addition, it may be that the women are more willing to acknowledge their needs and address them than are the men, and thus servicewomen score higher on such measures than the men, but their problems may be no greater, and thus they are more likely to get the help they need.

In addition, there was a significant effect of marital status on the M2C items of: “Problems Dealing with People,” “Taking Care of Chores,” and “Making Good Use of Free Time.” It is possible that these items on the reintegration scale were significant for marital status because it is often difficult, for various reasons, for one to leave the military, regardless of branch or length of service. it is possible that reintegrating back into a civilian lifestyle, wherein one must learn to change between identities, could be especially stressful and problematic It appears that for many of the women veterans who participated in this study, their marriages supported this transition, but not so for some of them and for some of the not married veterans. Thus, the non-married participants reported greater difficulty in their use of time and getting chores done, and difficulty relating to people in general (people who presumably do not have their military identification).

This is consistent with research, that finds that the military will introduce its own culture and strip away any sense of individuality, thus making it difficult for one to identify and mold back into a particular civilian role. [1] Demers further elaborated on how military indoctrination is where civilians are transformed into a collective group that shares a distinctive identity. Furthermore, upon reintegration, it was identified that women veterans and servicewomen had difficulty interacting with other individuals. [12] It is possible that this difficulty could affect other areas in life, such as taking care of responsibilities, such as chores, interacting with others, and making use of free time. It would appear that women with strong marital relationships, bonds, and support may have some difficulty in relating to others, taking care of chores, and making use of free time. However, married women are less likely than women who are not married to have significant difficulty reintegrating. It should also be noted that non-married service women often had other sources of support and strengths. This study was not designed to address those sources, and so those details should be addressed in future studies.

Relationship of Marital Status to PTSD Scores

Quite understandably, given men’s greater exposure to circumstances of combat, most of the prior research on the effects of combat exposure on mental health outcomes has either focused exclusively on men or included only a small subset of women in their samples. [2] Thus, there are few studies that can be consulted to draw conclusions regarding the differential impact of combat exposure on women. An examination of the broader literature on gender differences in trauma exposure and its consequences could interpreted to suggest that women might be more negatively affected by combat exposure and may report their symptoms openly. However, as noted above, the service women who deployed to combat zones did not report greater difficulties than those who had not.

Consequently, PTSD effects were not differentially associated with combat exposure, but marital status was a general predictor of problems not only associated specifically with reintegration (M2C-Q), but also in regard to reported PTSD symptoms. In this study, married women generally reported the lowest level of PTSD symptoms and symptoms improving since beginning of treatment (i.e., psychological treatment) more than the others. As stated earlier, having (a good) marriage appears to be a protective factor and is beneficial to the reintegration process and to mental health. Furthermore, research is not yet available on the longer-term implications of the reintegration difficulties of women veterans and servicewomen. It is known that some veterans struggle with mental and physical health problems following deployment. Street, et al., had asserted that combat deployments are not associated with a higher risk of mental health problems for women compared to men. [2] However, Street, et al., reported the lack of differences in post deployment PTSD may not necessarily mean that combat exposure has the same impact on women’s and men’s mental health. [2] Thus, it is possible that post deployment, PTSD may be influenced by a number of factors other than deployment to a war zone. Therefore, when facing difficulties of reintegration, this study found that it is helpful to have a protective factor, such as a strong source of support, to help in reintegrating back into civilian life.

This proposal correlates with research on the effects of PTSD on servicemembers. For example, recruits are trained to “never abandon their fellow warriors in combat and never show weakness to fellow warriors or to the enemy.” [12,14] Such collective values are generally referred to as the Military Culture. Research has shown that abiding by these values can be very difficult and traumatic for an individual regardless of gender. Diagnosing a service member or veteran with PTSD does not necessarily derive simply from combat experience, but perhaps to military culture, level of assimilation, coping abilities, social support, and other factors. [4,9,14] Thus, the servicewoman who participated in this study may not necessarily have full criteria to meet a DSM-5 PTSD diagnosis, however, they may be affected by other experiences in the military. It is important to note that many of the women veterans and servicewomen endorsed the item on the M2C-Q “I Feel Much Improved,” especially the married ones. In contrast, the women who identified as single, may not have sufficient support, or may not feel they have improved since deployment.

Thus, women whose marriage apparently worked as a protective factor and who had combat experience were less likely to endorse PTSD symptoms on the SPRINT scale. For example, they reported little to no relevant trauma with loss of enjoyment for things, keeping their distance from people, nor found it difficult to experience feelings. These findings were similar to those on the DAST-10. Women who were married were less likely to report neglect of their family because of drug usage or have any medical problems as a result of their drug use (e.g., memory loss, hepatitis, convulsions, bleeding, etc.). Thus, having a strong protective factor, such as a spouse who apparently is supportive, is beneficial to women veterans and servicewomen.

Need for Psychological Help for Service-Connected Problems Reported by Servicewomen

Sixteen of the 23 women reported that they think they need psychological help for service-connected problems. In regard to reintegration problems, they reported 5 specific problems on the M2C-Q in contrast to those women who said that they do not need help for service-related problems. The specific problems they reported were dealing with people, making new friends, keeping up friendships, getting along with their spouse and having difficulty feeling like they belong as a non-military person (citizen) (see Table 3).

It seems that all those specific problems have in common that these returning service members are reporting that relating to people in general as well as to those with whom they have on-going, significant relationships can be problematic for many of them. Although this study did not investigate specifically the kinds of problems that they were encountering with friends and spouses, it seems likely that a specific difficulty has something to do with how other people in general and even friends and spouses could relate to their service experience. Although we have seen that being married was apparently a protective factor, relating with one’s spouse could also be the biggest problem that returning servicewomen encounter.

Success in Reintegration

On the M2C-Q, many of the women suggested they had little to no difficulty in getting along, communicating, doing things together, or enjoying company. Thus, it is possible that these women who had served in the military (with or without combat exposure) endorsed having little to no difficulty in communicating their experiences pre and post deployment and were less likely to have difficulties reintegrating back into civilian life. Furthermore, these findings also suggest that women who had no trouble communicating with their spouse (or some other supportive resources or personal resources) were less likely to have drug use problems or difficulty in confiding, sharing personal thoughts, feelings, and described having a purpose and meaning in life. Subsequently, they reported less PTSD type symptoms.

Clinical Implications

There are possible suggestions to derive from these findings that may benefit women veterans and servicewomen. One area would be to offer support groups that are both formal and informal in which they would have the opportunity to share their stories and learn about practices for successful reintegration. [12] The findings of this study are very consistent with the proposal by Demers. These support groups might be integrated with activities that encourage imagination and facilitate veterans’ communication of their stories, and doing so in situations and settings in which they are comfortable.

For mental health professionals, it would be ideal to obtain military culture training to help understand the difficulties women in the military face, such as gender identity and roles, and sadly including discrimination, harassment and even sexual assual [14,19]. Possible transition specific groups for the women veterans and servicewomen and family members prior to reintegration would help with providing psychoeducation to assist in identifying red flags, such as PTSD symptoms. Last, reintegration classes that help educate servicemembers, men and women alike, on the dangers of PTSD symptoms, suicidality, SUD’s, military culture, and different roles they play in society.

The findings from this study could help clinicians in terms of learning how to recognize the possibility of early warning signs that may affect servicewomen’s mental and physical health. Probably the single most relevant finding among the effects found with the measures used in this study was the importance of a good support (person/people). Although other specific sources of support were not investigated in this study, some other such resources could include engaging in daily mindful relaxation, physical exercise, eating healthy, and seeking supportive relationships that all may minimize a person’s risk of mental health complications and reintegration difficulty.

In addition, this research assists in indicating the areas of reintegration difficulties that women veterans and servicewomen experience regarding: SUD, PTSD, and difficulty in reintegration adjustment. Another implication of the findings is that when assessing this population, it is crucial to look at individual items when utilizing scales so as not to miss highly specific individual problems. Furthermore, this research encourages other health care professionals to identify symptoms, triggers, and difficulties to reduce problems in reintegrating back into civilian life and roles. For example, although women veterans and servicewomen did not have any significant scores on the PTSD scale, many endorsed having difficulty with memories from military service. Thus, clinicians should not only look over every scale carefully, but also every item and ask further questions. It is possible that having reoccurring memories can cause more difficulty in other areas of life, such as relating to others, difficulty sleeping, and even the experience of physical pain.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are a number of limitations in this study. First, there are only 23 participants for whom adequate data could be used for analyses. However, as was noted in the study by Shivakumar, et al., (2017) in which they obtained significant results with as few as 16 participants, the twenty-three participants of this study can certainly provide meaningful findings. Second, this study was designed for individuals who identified as women; therefore, due to the specific sample, it does not speak to the difficulty other veterans and service members experience when reintegrating into civilian life. A third limitation relates to the nature of these reflective self-reports and the length of time between military enlistment, and last deployment, which has the potential for recall bias and response. [8] Fourth, servicewomen and veterans have to compete and cope with a number of roles and identities post deployment: as solider, comrade, student, sister, wife, and motherhood among other such roles and duties. Makowski proposed that it is possible the women may overestimate, or underestimate factors associated with readjustment and reintegration due to the various roles and identities they play. Fifth, the measures used may not have been sensitive to detect the specific issues these women face, or possibly the degree or nature of the difficulties they face.

Future research should consider these limitations and incorporate a larger and more diverse sample. In addition, it is important to examine if there is a difference in reintegration difficulties, PTSD, substance use, and level of military culture across all previous deployments/war involvement, not just the more recent combat exposures as those may not have been sufficiently identified. An example would be comparing women veterans who were enlisted during OEF/OIF with women from the Vietnam era. Another direction for future research would be to see if implementing reintegration skills training into military branches prior to reintegration into civilian life would alleviate some of the difficulties expressed by the servicewomen and veterans post deployment.

Summary and Conclusions

There were several significant findings that broaden our understanding of reintegration and possible factors that may also impair the level of reintegration. Focusing on mental health issues in recently returning women veterans and servicewomen, the findings provide indications of possible specific reintegration difficulties and identified several implications for practice and ways mental health providers could assist women. Despite readjustment issues such as threats to identity and SUD’s, participants of this study also exemplified women’s strength, their effective use of social support resources, and their ability to cope with difficult experiences. Similarly, it is apparent that the level of resiliency for women veterans and servicewomen may also vary among them and would require an assessment of the strengths and protective factors that foster healthy reintegration. It was also found that 30% of this study’s participants said they do not believe they need help with service- related psychological problems, as they suggest that a good support system, such as in a good marriage, would help with coping with psychological distress. It should also be noted that many of the not-married servicewomen also reported not having significant problems with reintegration. Thus, there are multiple sources of strength for these servicewomen that were not explicitly investigated in this study but that deserve delineation in future studies.

Female veterans and servicewomen face considerable challenges on returning from war; not only must they cope with the experiences of war with which all soldiers must come to terms, they must also overcome the consequences of the psychological war they fought with comrades. Despite the limitations, this study provides insight into the experiences of servicewomen and veterans. This study adds to the growing demand of research documenting the difficulties women veterans and servicewomen who were deployed face, as well as identifying their sources of strength. The views described by servicewomen and veterans of this study shed some light on the multifaceted and often difficult reintegration and readjustment experience of many women post deployment. Post deployment many women assumed their multiple civilian identities as mother, partner, daughter, professional, and friend. In addition, military culture had been engrained in them since bootcamp and finding their own identity post deployment has been known to have some serious effects. On re-entering the civilian world, returning veterans were, once again, thrust into a separation phase of passing from military identity to civilian identity. While the women who participated in this study identified specific areas of difficulty in reintegrating, they also showed their strengths and ability to handle their military experience.

References

- Timko C, Hoggatt KJ, Wu FM, Tjemsland A, Cucciare M, et al. (2017) Substance Use: Substance Use Disorder Treatment Services for Women in the Veterans Health Administration. Womens Health Issues 27(6): 639-645.

- Street AE, Dawne V, Dutra L (2009) A new generation of women veterans: Stressors faced by women deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin Psychol Rev 29(8): 685-694.

- Shivakumar G, Anderson EH, Surís AM, North CS (2017) Exercise for PTSD in Women Veterans: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Mil Med 182(11): e1809-e1814.

- Rona RJ, Fear NT, Hull L, Wessely S (2007) Women in novel occupational roles: Mental health trends in the UK armed forces. Int J Epidemiol 36(2): 319−326.

- Carney CP, Sampson TR, Voelker M, Woolson R, Thorne P, et al. (2003) Women in the gulf war: Combat experience, exposures, and subsequent health care use. Mil Med 168(8): 654-661.

- Cotton SR, Skinner KM, LM Sullivan (2000) Social support among women veterans. J Women Aging 12(1-2), 39-62.

- Kasinof, L. (2013). Women, War, and PTSD. Washington Monthly.

- Thomas KH, McDaniel JT, Haring EL, Albright DL, Fletcher KL (2017) Mental Health Needs of Military and Veteran Women: An Assessment Conducted by the Service Women’s Action Network. Traumatology 24(2).

- Koo KH, Maguen S (2014). Military sexual trauma and mental health diagnoses in female veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq: Barriers and facilitators to Veterans Affairs care. Hastings Women’s Law Journal 25: 27-38.

- Ganz A (2017) Is Mental Health Stigma Among Active-Duty Military a Cultural Problem? Dissertation.

- Carlson BE, Stromwall LK, Lietz CA (2013) Mental health issues in recently returning women veterans: Implications for practice. Soc Work 58(2): 105-114.

- Demers AL (2013) From death to life: Female veterans, identity negotiation, and reintegration into society. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 53(4), 489-515.

- Mankowski M (2013) Reintegration and readjustment experience, identity, and social support for women veterans returning from operation Iraqi freedom and operation enduring freedom: a qualitative study. Dissertation.

- Yudko E, Lozhkina O, Fouts A (2007) Regular article: A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. J Subst Abuse Treat 32(2): 189-198.

- Heslin KC, Gable A, Dobalian A (2015) Original article: Special Services for Women in Substance Use Disorders Treatment: How Does the Department of Veterans Affairs Compare with Other Providers?. Women's Health Issues 25(6): 666-672.

- Skinner H (1982) The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors 7(4): 363-371.

- Connor K, Davidson J (2001) SPRINT: A brief global assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 16(5): 279-284.

- Yamaguchi C (2019) Military culture and substance use as a coping mechanism. Dissertation.

- (2017) Women Veterans: The Long Journey Home. Disabled American Veterans.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.