Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Personality Factors and Their Roles on Individuals Modeling Social Media Trends and Behaviors

*Corresponding author: Rene Saghieh, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Anaheim, United States.

Received: October 05, 2023; Published: October 12, 2023

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2023.20.002697

Abstract

Social media, technology and online influencers are prominent and powerful tools that can expose individuals to information, behaviors, and languages that influence their behaviors, values, and beliefs. Of importance are factors that influence vulnerability to be influenced by social media. This study’s main goal was to examine several personality variables and their relationship to being influenced by social media through an “influencer.” Examined in this study were impulsivity, self-esteem, and social desirability. Participants responded to one of two vignettes. One vignette described the influencer with little detail and encouraged the respondent to project their own favorite influencer into the vignette. The second vignette attributed characteristics to the influencer that research has shown to be present in CEO and influential individuals. After the participants rated how likely they were to engage in a variety of behaviors, etc., endorsed by the influencer. The results indicated that individuals who scored higher in impulsivity were more susceptible to being influenced by the influencer compared to those with moderate or low impulsivity. It was also found that the influencer who was attributed fewer specific characteristics was more effective as an influencer. Most striking was that the participants who indicated they were likely to be influenced indicated it was more long-term behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs that were subject to influence rather than momentary, rushed actions or behavioral act. These findings revealed that social media is most influential when it strikes a chord “deep” within a person through messages from individuals who are perceived to be influential.

Keywords: Impulsivity, Influencers, Internet-users, Quantitative, Research, Treatment planning

Introduction

A common phenomenon is the extent to which people use and are influenced by social media. In what has been termed “the Information Age,” people don’t have to wait for the traveling troubadour, the town crier, a newspaper, or even the evening news to learn of the thoughts and actions of people far away-and those whom they have never met [1]. Research has shown that social media is widely viewed and accessed [2]. An individual’s personality traits and social desirability needs are believed to play a role in their behaviors, thought patterns, feelings, and how they react to both internal and external stimuli [3-7]. Furthermore, an individual’s personality may play a role in how they perceive the environment around them, which could play a role in the person’s likeliness to be influenced by social media [8,9]. Consequently, individuals’ interactions with social media can affect their perceptions of themselves and others [2]. A common term for the technology that brings the Information Age to ready access is social media. In that regard, various estimates are that there are about 2 billion individuals who engage in social media usage [10]. Examples of popular social media are YouTube, which is estimated to be used by 81% of Americans; Facebook, which is estimated to be used by 69% of Americans, followed by other social media platforms such as Instagram, Pinterest, LinkedIn, and more [11]. Because of the widespread and easy availability of social media, what is presented in that medium has a tremendous possibility of influencing the attitudes and behaviors of people. The influence of attitudes and behaviors is likely a result of social media users perceiving social support and life satisfaction from consuming social media [10]. Some individuals are likely more susceptible to being influenced by social media than others. Some personality characteristics of interest that might contribute to this are impulsivity and borderline personality traits. A common theme that runs through these characteristics is often an inflated, yet vulnerable, self-image. Thus, these characteristics make one’s self-esteem fragile even though, on a conscious level, these people would claim high self-esteem and claim self-approval for their behavior even when it is counterproductive. Individuals may strive to present themselves in a good light and generally tend to refrain from reporting potentially damaging opinions and behaviors as a result of impression management, which derives from social desirability bias [12-16]. An individual’s vulnerability to social influence can be related to their engagement in social comparison and their perception of others, especially as susceptibility to social influence, may play a role in their reported self-esteem [17]. Consequently, social influence and social comparison tend to be connected to certain aspects of personality. An extensive amount of literature on social influence and personality traits/characteristics provides ample evidence of the reality that personality characteristics are associated with vulnerability to social influence [18-20]. Social influence can function independently from an individual’s personality and is identified as having three unique types, such as conformity (majority influence), obedience, and minority influence [21,22]. Additionally, the usage of the “six principles of persuasion” has been found to play a role in social influence [23]. Common social influences that play a role in individuals who consume social media are compliance, internalization, and identity, which are all types of conformity (majority influence) [24]. When examining social influence, research has found that personality aspects, such as Machiavellianism, are tied to the use of specific types of social influence techniques, including manipulation and deceit [25]. Individuals who are influencers in social media are purported to tend to score high on Machiavellianism [20]. Such influencers tend to be perceived as dominant, confident, power-oriented, ambitious, and intelligent [20,25]. Two other personality aspects that commonly play a major role in social influence are neuroticism and impulsivity. Elements of an individual with neuroticism traits, such as low self-esteem and inconsistent self-concept, lead to engagement in social comparison and thus a vulnerability to present themselves with socially condoned (desirable) characteristics as defined by an influencer [17,26,27].

The Present Study

This study assessed specific personality characteristics of vulnerable self-esteem, engagement in social comparison, and impulsivity. These personality dimensions were hypothesized to increase individuals’ susceptibility to being socially influenced and engaging in behaviors and beliefs adopted from influencers through the social influence process of exposure to influencers on social media. Due to the widespread use of social media, this study focused on the participants’ engagement and reactions regarding behaviors observed and modeled by social media influencers. Participants were recruited through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Reddit. Participants were randomly assigned a vignette that depicted and defined a social media influencer by using personality characteristics that have been found commonly in Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) and social media influencers. These characteristics were based on Machiavellianism personality traits such as dominance, being strategic, manipulative, ambitious, and power oriented [15,25,28]. An alternative vignette gave a minimal descriptor of the influencer, directing the respondent to think in terms of an individual whom they respect, admire, and possibly follow online who would influence them. Once the vignette was presented, the participants were asked to report the likelihood of their engagement in behaviors, attitudes, values, etc., related to the influencer.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited through Reddit (forums r/psychology research and r/Sample Size), the researcher’s personal Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram accounts. A recruitment message was posted on the forums, feed, and story with the recruitment message in either text or image, along with one of two links to Survey Monkey. Those who accessed the study first received a screening questionnaire. Those who did not meet the screening criteria were directed to an exit page and thanked for considering participating. Those who met the eligibility criteria were presented with the Informed Consent form. Those who did not click “I agree to consent” were sent to an exit page and thanked for considering participating. The participants who clicked I agree with were asked to complete a demographic questionnaire. A total of 68 participants completed all aspects of the study out of the 80 who initially indicated an interest in the study. There were 29 female participants, 30 male participants, eight transgender/nonbinary participants, and one participant that did not disclose their genders. Thirty-three participants reported being White/Caucasian, 27 participants reported being Asian/Pacific Islander, five participants reported being Hispanic/ Latinx, and three individuals reported being other or mixed race. Participants’ age varied between 18 years old to 51 years old, with the average age being 27.07 (SD=7.958). All participants used social media once a day and used one or more of the following social media platforms: Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, YouTube, TikTok, or Instagram.

Measures

Vignettes

Participants were randomly assigned one of two vignettes developed by the researchers. One link to the study led to Vignette 1 and the other to Vignette 2. After reading the vignette, participants were asked to answer questions related to their responses and behaviors to the influencer described in the vignette. The first vignette was a “projective” measure that consisted of two sentences depicting an influencer that the participant was to image as being respected, admired, and influential to the participant. This vignette read as follows: “Imagine an individual whom you respect and admire. Think of someone you follow online who could possibly influence you.” The second vignette attributed characteristics to the influencer such as ambitious, outgoing, consistent, committed, and conscientious. The second vignette read as follows: “An influencer is an individual who is very ambitious and outgoing. They are usually good-looking and charismatic. An influencer appears to be very social and is often seen as the leader of their group of friends and a prominent figure in the community. The influencer owns a business, is their boss, and often owns some luxury items that they could buy from their work and the support from individuals online. They often post content daily on different platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, Facebook, and others. Individuals around you praise this influencer for the work they have done and how much they were able to achieve at their age.

After reading the vignette, participants were all asked: How likely would you say you would engage in the following behaviors with the knowledge you know so far about this influencer?”. Participants were asked to answer 13 questions concerning their reactions to the vignette. Each question allowed participants to rate their level of agreement on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 being “Strongly Disagree” to 7 being “Strongly Agree” with different statements related to their levels of involvement and interactions with the influencer and their content.

Demographic Questionnaire

The questionnaire asked for age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, and the highest level of education. The demographics questionnaire also included how often individuals spend time on social media, what social media platform is used, and what content is consumed.

Rosenburg Self-Esteem Scale

The Rosenburg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) is a 10-item measurement that asks respondents how strongly they agree or disagree (1 = Strongly Agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Disagree, 4 = Strongly Disagree) with statements regarding their self-esteem. A total score was derived by adding up the ratings for each item. When scoring the RSE, items 3, 5, 8, 9, and 10 are reversed. For this study, score values were changed from 0-3 to range from 1-4, which shifted the scale ranges from 0-30 to 1-40. The classification criteria for categorizing scores used for this study were in accordance with [29]. Scores between 10 to 24 were categorized as low self-esteem, scores between 25 to 35 were categorized as normal self-esteem, and scores between 36 to 40 were categorized as inflated self-esteem.

Brief Self-Control Scale

Participants were asked to complete the Brief Self-Control Scale, which is a 13-item questionnaire. Each item allows participants to rate their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale from “very much like me” to “not at all like me.” [30]. When scoring the Brief Self Control Scale, items 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, and 13 were reverse scored. After being reversed, all scores were added together, and scores in the range of 31 to 48 were considered normal. Scores that were between 13 to 30 were categorized as low levels of self-control, 31 to 48 were categorized as medium levels of self-control, and scores higher than 49 to 68 were categorized as high levels of self-control. Thus, low scores reflect high impulsiveness, and high scores reflect low impulsiveness.

Marlowe Crown Social Desirability Scale

Participants were asked to complete the Marlowe Crown Social Desirability Scale, a 33-item questionnaire [31]. Each item allows participants to rate whether they agree with a statement or not by responding “true” or “false.” All items are added and scored. Scores were categorized into three different levels: Low (0 to 8 total score), medium (9 to 19 total score), and high social desirability (20 to 33 total score).

Procedures

For those participants who clicked on the “I consent” button on the Informed Consent page, the following measures were presented in the following order: one of the two vignettes, the 13 questions concerning the vignette, the demographic questionnaire, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, the Brief Self-Control Scale, and the Marlowe Crown Social Desirability Scale. After completing all of the questionnaires, participants were redirected to the Debriefing statement. The questionnaires and vignettes took approximately 25 to 30 minutes to complete. Participants were able to discontinue their participation at any time by simply clicking exit. All demographic and survey responses were kept on a password-protected computer.

Results

Analysis of the Relationships of Vignettes to Self-Esteem, Impulsiveness, and Social Desirability Responding

Measures of self-esteem, impulsiveness (self-control), and social desirability responding were administered to each participant. Although participants were randomly assigned to either Vignette 1 or Vignette 2, it is possible that the participants assigned to a particular vignette differed regarding one or more of those characteristics. Therefore, ANOVAs were conducted to check to see whether participants who responded to a particular vignette differed on any of those domains from those who received the other vignette. There were no significant effects found for self-esteem, impulsiveness, nor social desirability between the vignettes. Thus, any differences obtained between the vignettes as to how the participants answered any of the 13 questions regarding the degree of influence the influencer would have with them are not confounded by the participant’s degree of reported self-esteem, impulsiveness, nor social desirability responding.

Differences between the Vignettes in Degree of Influence of the Influencer

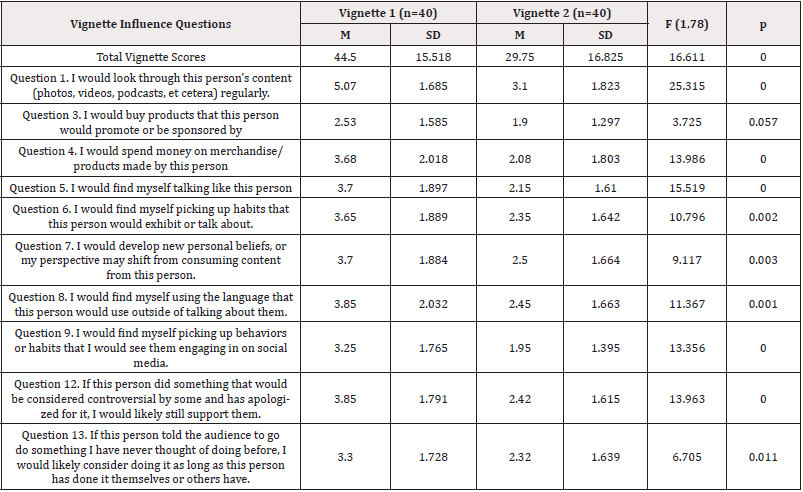

The influencer in Vignette 1 could be somewhat of a “projective” vignette that permitted the participant to form their specific image of the influencer in contrast to the more detailed description of the influencer in Vignette 2. Participants were asked 13 questions regarding the influencer’s possible degree or likelihood of influence on the participant. A significant difference was found for the Vignette Total Score between the two vignettes (F (1,78) =16.611 p =.00.). Therefore, 13 ANOVAs were conducted, one for each of the 13 questions to see if there were differences in how influenced the participants reported they would be on each of the 13 components of the vignette Total Score of Vignette 1 compared to Vignette 2. Statistically significant differences were found for 10 of the 13 questions. These significant differences are reported in Table 1, which contains the means, standard deviations, and F test results for the significant differences. It can be seen from Table 1 that regarding these 10 questions, participants who read Vignette 1 indicated being more likely to be influenced by the influencer in Vignette 1 compared to the degree to which participants who read Vignette 2 indicated how likely they were to be influenced by the influencer in Vignette 2. It should be noted that the middle point on the influence scale is 4.0. Thus, in general, participants were reporting they were not highly likely to be influenced by influencers, and that influence was most likely to occur when the participant (social media user) seems to find a “connection” with the influencer.

Table 1: Means, Standard Deviation, F, and P values for the rating of the vignette questions for each of the vignettes for which there were significant differences and the total scores.

It can also be seen in Table 1 that there were no significant differences between the vignettes on questions 2, 10, and 11 [Question 2 “I would buy products that this person would mention personally using or recommend”; Question 10 “I would participate in social media trends that this person would engage in”; Question 11 “I would consider myself a ‘Stan’ of this person” (The term “Stan” is used to describe a devoted fan)]. It appears that knowing a lot about the influencer does not reduce perceiving oneself as a “devoted fan” (Stan) but does reduce the degree of influence that the influencer has.

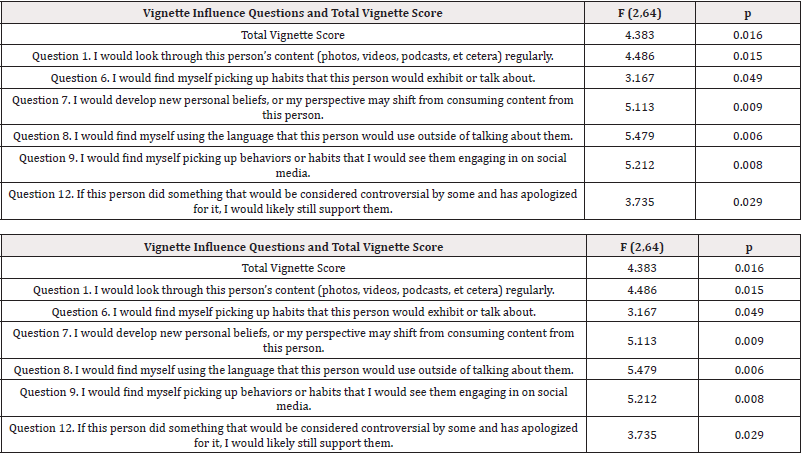

Relationship of Self-Control/Impulsiveness to Being Influenced

A major theory of this study was that individuals who scored higher in impulsiveness (scored low in self-control) would be more likely to be influenced than those who scored lower in impulsiveness (scored high in self-control). This hypothesis was tested by an ANOVA using three levels of self-control (high, medium, and low) for each of the 13 questions compared to the two levels (high/low) categorization prior research utilized for this measure. Statistically significant effects were found for Self-Control/Impulsiveness on the Vignette Influence Total Score and 6 of the 13 questions. These results are reported in (Table 2). To determine which levels of self-control differed from which levels for each of the 6 questions for which there were significant differences among the three levels of self-control (impulsiveness), Multiple Comparisons were made using the LSD (Least Significant Difference) statistic. Those results are presented in Table 3. It can be seen in Table 3 that in general, participants rated as low in self-control (high in impulsiveness) reported a greater tendency to be influenced than those rated as moderate or high in self-control. Thus, it was found that those who were especially low in self-control (high in impulsiveness) reported a greater tendency to be influenced by the influencer, as was reflected in 6 of the 13 influence questions (and this difference held across vignettes).

Table 2: F and P values for the rating of the vignette influence questions for the questions for which were significant effects of self-control and the total vignette score.

Table 3: Means, Standard Deviations, and p values comparing each level of Self Control with each level of self-control where there were significant overall F ratios on the Vignette Influencer Questions.

Self-Esteem and Influence

A single, statistically significant effect was found for Self-Esteem on question 7 of the vignette, F (2, 65) = 4.779, p = .011. These means and SDs are reported in (Table 4). According to the classification criteria for categorizing scores as specified in [24]. and for this study, response categories were changed from 0-3 to a range of 1-4. This raised the ranges for total scores from 0-30 possible to 10-40 as the possible Total score. Based on the actual scores obtained by the participants in this study, scores between 10 to 24 were categorized as low self-esteem, scores between 25 to 35 were categorized as normal self-esteem, and scores between 36 to 40 (the highest score obtained by any participant) were categorized as inflated self-esteem in accord with [24]. To determine which levels of self-esteem differed from which levels for the question for which there was a significant overall effect of self-esteem, Multiple Comparisons were made using the LSD (Least Significant Difference) statistics. Those results are presented in Table 4. It can be seen in Table 4 that participants rated as low in self-esteem reported a lower tendency to develop new personal beliefs or shifts in perspective from consuming content than those rated as moderate or high in self-esteem.

Discussion

This study was designed to examine impulsivity, self-esteem, and social desirability and their relationship to vulnerability to be influenced by social media influencers. These factors were examined as prior research and theorizing proposed that there is a likelihood of individuals with these characteristics being influenced by influencers in social media [17,26,27]. There were two different influencers described in one of two vignettes. In one vignette, very little was described about the influencer, and the participant was encouraged to imagine an influencer whom they follow. In the other vignette, multiple characteristics of the influencer were detailed as identified in the literature as being characteristic of influencers. The study found that participants reported higher levels of influence regarding the influencer in the projective vignette It would appear that when the individual finds something about the influencer that appeals to them, they become more “available” to be influenced. In contrast, it would appear that the more one knows about the influencer, the less power the influencer has. Additionally, the “projective” vignette may be more effective due to the participant previously being influenced by the influencer as they projected someone who has influence with them (Cialdini, 2007) [23]. In contrast, participants may not have been as influenced by the influencer in the second vignette due to some of the specific factors that were attributed to the influence, as it is possible that one or more such characteristics were not appealing to the participants or did not align with their possible definition of an individual who would influence them. Future research should address which of the multiple characteristics attributed to the influencer in the second vignette are differentially powerful.

Conceptual Grouping of Vignette Questions

After the differences between the vignettes in degrees of influence of the influencer were analyzed, two categories for grouping the 13 questions were developed for the questions. It is possible that the 13 questions can be grouped into two “sub-scales” related to short-term or longer-term influences. The two sub-scales for influence could be termed: Short-Term Changes and Long- Term Changes. The questions in the Short-Term l Changes include questions 1, 3, 4, 5, and 13 (Question 1. I would look through this person’s content (photos, videos, podcasts, et cetera) regularly. Question 3. I would buy products that this person would promote or be sponsored by; Question 4. I would spend money on merchandise/ products made by this person; Question 5. I would find myself talking like this person; Question 13. If this person told the audience to go do something I have never thought of doing before, I would likely consider doing it as long as this person has done it themselves or others have).

The questions in the Long-Term Changes include questions 6, 7, 8, 9, and 12 (Question 6. I would find myself picking up habits that this person would exhibit or talk about; Question 7. I would develop new personal beliefs, or my perspective may shift from consuming content from this person; Question 8. I would find myself using the language that this person would use outside of talking about them; Question 9. I would find myself picking up behaviors or habits that I would see them engaging in on social media; Question 12. If this person did something that would be considered controversial by some and has apologized for it, I would likely still support them). The significance of delineating the vignette questions into two sub-categories or sub-scales (Short-Term and Long-Term Changes) is that it may allow for further assessment of the level of an impact social media content may have on consumers regarding behaviors/cognitions that could either be temporary and changed or long-standing and difficult to change. An implication of the possible significance of differentiating short and long-term influences of social media may be seen in the findings regarding self-control/ impulsiveness discussed next.

Self-control/Impulsiveness

It was also expected that a person’s level of self-control (impulsiveness) would be related to being susceptible to influence. The study found that participants who scored low on the self-control scale (high in impulsiveness) reported a greater tendency to engage in both short-term and long-term changes than those classified as moderate or high in self-control. These short-term and long-term changes included consuming content, developing habits/behaviors, new personal beliefs/perspective shifts, new language usage, and commitment to supporting the influencer. This finding is meaningful since impulsivity is a vulnerability marker for different psychological disorders and risky behaviors [32-34]. Thus, finding that it is longer-term, more basic aspects of people’s behaviors, attitudes, and values that get influenced by social media has significant social implications. Due to impulsivity being a vulnerability factor, it can be informative and important to be able to understand how this personality trait, paired with exposure to influencers, may result in short-term and long-term behavioral changes. These changes may affect interpersonal relationships and result in impairments in functioning (if the behaviors are risky). Also, when dividing the questions into two possible sub-scales of short-term and long-term behavioral changes, it was found that the effects reported here of self-control and influence that were found on six of the questions was found on only one of the items proposed here for the Shortterm Behavioral changes sub-scale, while the other five were on the proposed Long-term Behavioral Change scale. It is possible that what has been found here is a very powerful/profound aspect of the relationship of self-control/impulsiveness to being influenced that when that operates, it is because it is striking a deep aspect of the person and thus relates to long-term effects on the person – which contrasts with an immediate (impulsive) short- term influence.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Limitations that participants may not have been a representative group of the general population due to unknown factors affecting who chose to complete the study. Another limitation of the study was the fact that multiple participants opted out from continuing to participate in the research during different points of the study, which may have resulted in the data being skewed in some way. Due to the study being administered remotely, there may have been inconsistency with the standardization of the conditions under which participants completed the study. A limitation within the study can be found in the vignettes and questions addressing the amount of influence participants experienced relating to the individuals described in the vignettes. The vignettes and questions were not tested for content validity, construct validity, and face validity before the research was conducted, which may have resulted in questions 2, 10, and 11 having no significance. Question 2, “I would buy products that this person would mention personally using or recommend” could be reworded to, “I would buy or use products that this person would mention personally using or recommending” to lessen the focus on investing money into products and more focusing on the short-term behavioral change that is shifting their product consumption to match the influencer. Question 11, “I would consider myself a ‘Stan’ of this person” (The term Stan is used to describe a devoted fan)] could be improved by utilizing the word “fan” instead of “Stan” as the wording of the question could be perceived as the question asking individuals if they engage in obsessive fan behavior. The vignettes and questions may require further editing and research for future studies to establish that the vignettes and questions are appropriately measuring and covering the construct of both influential individuals and levels of influence being experienced by the participants. The vignettes and questions require to be testing for reliability, validity, and test bias and require to be standardized within the population.

Another limitation is the possibility of respondent bias and the fact that the population sample of social media users isn’t certain and requires one to delineate what aspects of social media are being investigated. This is due to the variation of populations that may be a part of different interest groups within social media, depending on their purpose and use of social media. For example, the population of individuals utilizing social media for political content could vary differently from individuals utilizing social media for entertainment, social relationships, sports, and more. The population that was selected from these social media sites and that agreed to participate in the study may have presented characteristics that limit the generalizability of the study, such as gender, ethnicity, education, marital status, and more.

Summary and Conclusions

Social media is widely used around the world and can provide online users with access to a wide variety of content and information that can be useful, entertaining, useless, and at times harmful. Due to social media’s ramped usage, researchers and clinicians need to understand its effects on individuals who use it and how it can influence cognition and behavior. With influencers rapidly gaining a massive number of views and consumers, it’s crucial to be able to understand how personality traits of the viewers, such as impulsivity, may result in short-term and long-term behavioral changes. This study examined the impact of several personality traits (impulsivity, self-esteem, and social desirability) and the likelihood of individuals disclosing being influenced by either an influencer of their choice or an influencer that has been depicted as having specific characteristics that research suggests would be effective for an influencer.

It was found that individuals with higher levels of impulsivity were more likely to report being influenced. An unexpected finding was that longer-term behavioral and personality characteristics were most susceptible to influence. This implies that there may be a relationship between consumption of the influencer’s content, impulsivity, and long-term behavioral changes in individuals consuming social media. Further exploration and research are required to better understand these relationships, and the impact these behavioral changes may be having. Further research will help to identify the power social media has and for whom that power is effective.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- (2021) BroadbandSearch.net. (n.d.). Average time spent daily on social media (latest 2020 Data). BroadbandSearch.net.

- Allen S (2019) Social media's growing impact on our lives. American Psychological Association.

- Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Denissen J, Penke L (2008) Motivational individual reaction norms underlying the Five-factor model of personality: First steps towards a theory-based conceptual framework. Journal of Research in Personality, 42: 1285-1302.

- Hoyle RH (2006) Personality and self-regulation: Trait and information-processing perspectives. J Pers 74(6): 1507-1525.

- Holey RH, Sherrill MR (2006) Future orientation in the self-system: Possible selves, self- regulation, and behavior. J Pers 74(6): 1673-1696.

- Morf CC (2006) Personality reflected in coherent idiosyncratic interplay of intra- and interpersonal self-regulatory processes. J Pers 74(6): 1527-1556.

- Corr PJ, Matthews G (2020) The Cambridge Handbook of personality psychology. Cambridge University Press.

- Herringer LG, Haws SC (1991) Perception of personality traits in oneself and others. The Journal of Psychology 125(1): 33.

- Primack BA, Escobar Viera CG (2017) Social Media as It Interfaces with Psychosocial Development and Mental Illness in Transitional Age Youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 26 (2): 217-233.

- Auxier B, Anderson M (2021) Social media use in 2021. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech.

- Goffman Erving (1959) The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books.

- Paulhus, Delroy L (1984) "Two-component Models of Socially Desirable Responding." Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 46(3): 598-609.

- Paulhus, Delroy L (1986) "Self-deception and Impression Management in Test Responses". New York: Springer: 143-165.

- Paulhus, Delroy L (2002) "Socially Desirable Responding: The Evolution of a Construct". The Role of Constructs in Psychological and Educational Measurement: 49-69.

- Paulhus, Delroy L, Reid, Douglas B (1991) "Enhancement and Denial in Socially Desirable Responding". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 60(2): 307-317.

- Buunk A P, Gibbons F X (2007) Social comparison: The end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 102(1), 3-21.

- Krasner L, Ullmann L P (1973) Behavior influences and personality, the social matrix of human action. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Mehrabian A (1970) Tactics of social influence. Prentice-Hall.

- Harkins S G, Williams K D, Burger J M (2017) The Oxford Handbook of Social Influence. Oxford University Press.

- Moscovici S (1976) Social influence and social change. London: Academic Press.

- Moscovici S (1980) Toward a theory of conversion behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances, In experimental social psychology 13: 209-239.

- Cialdini R B (2007) Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. New York: Harper Collins.

- Rosnau K, Hashmi SS, Northrup H, Slopis J, Noblin, et al. (2017) Knowledge and Self-Esteem of Individuals with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1). J Genet Couns 26(3): 620-627.

- Freberg K, Graham K, McGaughey K, Freberg L A (2011) Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review 37(1): 90-92.

- Watson D, Suls J, Haig J (2002) Global self-esteem in relation to structural models of personality and affectivity. J Pers Soc Psychol 83(1): 185-197.

- Amirazodi F, Amirazodi M (2011) Personality traits and self-esteem. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 29: 713-716.

- Rauthmann JF, Kolar G (2012) How "dark" are the Dark Triad traits? Examining the perceived darkness of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Personality and Individual Differences 53: 884-889.

- Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone A L (2004) High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success. J Pers 72(2): 271-324.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Borderline Personality Disorder. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th).

- Crowne DP, Marlowe DA (1960) A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. J Consul Psychol 24: 349-354.

- Paulhus DL, Williams KM (2002) The Dark Triad of Personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality 36(6): 556-563.

- Verdejo García A, Lawrence AJ, Clark L (2008) Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: Review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers, and genetic association studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32(4): 777-810.

- Reynolds BW, Basso MR, Miller AK, Whiteside DM, Combs D, et al. (2019) Executive function, impulsivity, and risky behaviors in young adults. Neuropsychology 33(2): 212-221.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.