Case Study

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Responsible International Management: An Imperative for a Connected and Sustainable World in the Tunisian Dates Sector: A Case Study

*Corresponding author: Nefissa salma BEN MAHMOUD, Prisme Laboratory, ISG Tunis, University of Tunis, Tunisia +Crego Laboratory, IAE Dijon, University of Burgundy, France.

Received: December 15, 2023; Published: January 15, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.21.002802

Abstract

Over the past years, Global Value Chains (GVCs) have gained importance, proving particularly crucial due to contextual turbulences such as the Covid pandemic, political, military, and socio-economic factors. This recognition further strengthens the interest and relevance of GVCs in international literature, especially in the fields of international management and corporate sustainability. By focusing on agricultural sustainability and Inter-Organizational Relationships (IOR), our research positions itself at the heart of a complex and ever-evolving domain. Through our in-depth one case study of BENI GHREB company, we aim to make a significant contribution by shedding light on sustainable interactions between organizations (exporter-importer) operating in the GVC of Tunisian dates. Our approach considers the specificity of this context while closely examining how organizational dynamics influence sustainability in this specific domain.

Keywords: International Management, Inter-Organizational Relations (IOR), Agricultural Sustainability, Tunisian Dates, BENI GHREB case study

Abbreviations: IOR: Inter-Organizational Relations; CVGA: Global Agricultural Value Chain; GE : Grande Enterprise; SME: Small and Medium Enterprise

Case Report

In an ever-changing world, responsible international management is an essential pillar of the success of companies operating on a global scale. Today, the quest for sustainability and responsibility are significant issues in a globalized context. Indeed, the course of life is disrupted by various events such as health crises, environmental shocks, disasters, poverty and climate change. And these elements have prompted companies to adopt a more responsible and sustainable approach to their management. Responsible international management is about integrating these sustainability principles into almost all of the company’s activities, whether at the strategic, operational or cultural level. Inter-Organizational Relations (IORs) play a key role in providing the most effective way to build collaborative relationships, promote shared respon sibility and shape sustainable practices within a globalized and ever-changing ecosystem.” Research on network typologies and IORs has evolved significantly over time, resulting in a distinction into three fundamental types that are essential for interpreting value chains, now CV for short, on an international scale [49]. These three types include formal networks (such as relationships with customers, suppliers, distributors, etc.), informal networks (involving family, friendship or other personal relationships), and finally, intermediary networks (which include relations with chambers of commerce, research institutes, trade promotion agencies, and internationalization support agencies). without necessarily involving commercial transactions).

This article focuses on two fundamental concepts, namely agricultural sustainability in the date sector in Tunisia and the IORs that link the strategic actors of CVA of France and Tunisia. Located in the heart of southern Tunisia, our field of study allows us to explore in depth these two crucial areas and the relationship between the two. The first chapter of our analysis delves into the complex world of agricultural sustainability in Tunisian date production. By taking a close look at agricultural practices, environmental challenges and socio-economic issues, we provide essential insights into how the sector is addressing the issue of sustainability. In the second chapter, we turn to the IOR’s between the links of the CVGA of the date between France and Tunisia. Our objective is to explore how these partnerships and collaborations shape the economic and strategic dynamics between the two countries, with a focus on their positioning in relation to responsible international management. Based on field observations, and through the analysis of interviews we conduct with different stakeholders such as: farmers, exporters, importers, experts, etc. We present some initial results of our research, thus offering a significant contribution to the existing literature.

Our approach aims to enrich the understanding of issues related to agricultural sustainability and Rios in the Franco-Tunisian context. In short, this article is part of a desire to actively participate in national and international debates, while broadening the reflection on the academic and practical levels.

Literature Review

Agricultural Sustainability

Expectations for the adoption and improvement of sustainable practices are growing steadily, suggesting that public and private institutions will eventually impose these practices in different sectors of activity [15,53,20]. This development underscores the emergence of sustainability in response to a growing awareness of an impending environmental crisis at the end of the twentieth century, marking a major turning point in world history [15,53,20]. Today, humanity and contemporary businesses are facing major challenges in terms of agricultural sustainability, which essentially concerns the preservation of our planet’s ecosystems [47,57]. Indeed, over the past fifty years, there has been an increase in awareness of the impact of social and environmental issues on the decisions of business leaders [13,5,36]. Environmental concerns, including climate change, have sparked widespread mobilization with a significant increase in power [35,23,47]. In addition, concerns about poverty, growing inequalities between societies, and social tensions have heightened the urgency of acting from a sustainable development perspective [23,47,35].

These developments highlight the relevance of the fundamental issues of agricultural sustainability, which transcend the environment, the economy, food security and the well-being of populations. At the forefront is the pressing need to preserve essential natural resources (environmental issues), including soil, water and biodiversity. Agricultural sustainability focuses on ensuring that agricultural practices do not harm these vital resources, so that they can be passed on intact to future generations. From this perspective, food security (a social issue) emerges as a cornerstone of reflection. It is a global challenge to produce enough food for an ever-growing population while ensuring equitable access to these precious nutritional resources. Finally, to complete this complex picture, the promotion of environmentally friendly agricultural practices, such as organic farming and integrated crop management, is of crucial importance to minimize the environmental impact of modern agriculture. At the same time, the economic issues related to agricultural sustainability are of great importance, affecting the sustainability of farms and the reduction of disparities within the sector. This amounts to a balancing act where profitability and fairness must coexist harmoniously.

These fundamental issues of agricultural sustainability require a comprehensive approach, integrating international coordination and a multidisciplinary perspective, to address the complex challenges facing the agricultural sector. As a result, sustainability has become a key and universal priority, attracting increasing interest among politicians, managers, journalists, activists, and businesses Bansal, et al., (2019). This concept has become a key driver in our current world, prompting actors to rethink their approach to development and find balanced solutions to meet current needs without compromising the resources and opportunities of future generations [4]. Sustainability, therefore, aims to ensure intergenerational equity [4]. To fully understand sustainable development, it is fundamental to return to its central definition as formulated in the Brundtland Report in 1987 and supported by various authors, including [10]. According to this definition, sustainable development seeks to meet the needs of the present without compromising those of future generations. This vision emphasizes the balance between economic, social and environmental dimensions to ensure an equitable future. Sustainability, a multidimensional concept, is attracting increasing interest in various fields such as environmental sciences, economics and social sciences [23]. However, it stems from a rich and complex history influenced by various intellectual and political currents of thought [30].

The origins of sustainable development go back decades, marked by influential works such as Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” in 1962 and the Club of Rome report in 1972, known as “The Limits to Growth” [37] Delaunay, et al., (1972) Egle, et al., (2017). Over time, the understanding of sustainability has broadened to encompass economic and social dimensions in addition to the environment, taking a holistic approach. This conceptual evolution took root within the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in the 1980s, before being popularized by the Brundtland Report, also known as “Our Common Future”, published in 1987 by the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development [6,16]. This seminal report played a pivotal role at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, leading to the creation of Agenda 21, an action programme for sustainable development. Agenda 21 puts forward strategies and actions to balance environmental, social and economic aspects at the local and global levels, in the global context of sustainability.

IORs

Based on pioneering research in sociology and social psychology, social exchange theory asserts that relationships between or ganizations are primarily motivated by the pursuit of self-interest and the anticipated benefits it can generate, referred to as expected outcomes [33,50]. [12] define IORs as intentional and recurring interactions that occur between two or more organizations, with the aim of pursuing common goals. [19] defines them as links, both socially and economically, between organizations. These definitions highlight the intentional, recurring, and cooperative nature of IORs. Research on IORs is driven by the complex context of today’s global environment, in which companies must collaborate with other organizations to address environmental, social, and economic challenges. Through their research, researchers aim to understand the different dimensions of IORs, including their nature, origins, justification and consequences [41].

IORs are divided into two main categories:

i. IORs between competing firms occur between organizations that compete directly with each other. They can be adversarial, but they can also be cooperative.

ii. Non-competing firms occur between organizations that do not compete directly with each other. They are generally more cooperative and aim to create synergies or share resources.

In the agri-food sector, the concept of vertical coordination refers to the coordination of the different stages of food VAD [48]. There is a great deal of interest in vertical coordination in the recent literature on the evolution of the agricultural sector, and this tends to intensify over time. Indeed, closer coordination through contracts, alliances, partnerships and vertical integration is replacing coordination through the market [48]. Vertical relationships are part of a “complementary logic” [14]. In a vertical relationship, business-to-firm transactions occur at sequential stages of a GVC [8]. Each actor belonging to this structure has a specific activity to carry out in the GVC [45]. According to [27], agricultural economists believe that vertical coordination of markets is particularly important in the agri-food industry because of its complexity, the large number of firms involved in one or more stages, and the relative perishable nature of the products involved. Agri-food sectors in many countries are witnessing a shift towards closer vertical coordination, which involves a combination of agriculture and industry. Generally speaking, the vertical linkage orientation is justified by several technological, regulatory and financial reasons, in addition to changes in consumer preferences (quality, food safety, etc.). Vertical coordination refers to the means by which products move through the GVC from production to consumption [27]. It encompasses several transaction opportunities from market to vertical integration. In the literature, this concept has taken on several meanings, but the common idea lies in the fact that the firm sometimes chooses to internalize certain operations instead of using an external actor. Vertical coordination includes several intermediary forms such as strategic alliances, joint ventures, contracts, etc. It includes several modes of coordination, and there are three main modes of coordination in the agricultural sector that can be identified[48]

I. The market.

II. Contracts.

III. Vertical integration.

These relationships can be dyadic, involving only two organizations, or multiple, encompassing huge networks that include many organizations [12]. In today’s complex global environment, it becomes crucial for companies to strategically assess and manage their relationships with their customers and suppliers in order to provide added value to the end customer [41]. Small firms use RIOs as a tool to protect themselves from environmental uncertainty, improve their performance and ensure their survival [39]. At a time when competitiveness is increasingly defined by the ability to innovate, access to knowledge has become a central issue in organizations. Ior’s have become a key topic in the areas of strategy, and the intention of companies is oriented towards setting up new business activities in collaboration with other companies to deal with the complex problems related to their long-term development. This approach is frequently used to benefit from partners’ complementarities, share the costs and risks of updating and developing innovation, as well as to gain a superior competitive advantage [2]. In this logic, cooperation constitutes a barrier to entry, making innovation difficult to imitate Borgatti, et al., and Foster, et al., (2003).

Linking Ior’s and Agricultural Sustainability

IORs are relationships that can have a positive or negative impact on agricultural sustainability and vice versa. In this study, we focus on the deep links between IOR and agricultural sustainability in the specific date sector in Tunisia. Organizations operating in the date sector face multiple strategic choices related to their IORs, such as partnerships with other players, certifications, and power dynamics within the sector.

The concept of sustainability and the central role of stakeholders are seamlessly intertwined, forming an essential partnership to move towards a sustainable future. It is crucial to recognize that these stakeholders play a critical role in advocacy. As [35] point out, “sustainability can be seen as a central point around which societal actors gather.” Therefore, efforts to promote sustainable agriculture rely on the equitable sharing of risks and benefits, as well as actions such as collaborative planning, product development, information exchange, and coordination among GVC actors [38]. To create a sustainable future, companies need to align their strategic and operational goals with the Sustainable Development Goals [44].

Collaboration within a GVC can be understood as any action or activity where actors and/or organizations achieve mutually beneficial results by working cooperatively [24,46]. Studies by [9] as well as [31] concluded that collaboration within GVCs can have a significant positive impact on innovation and sustainable development. This work highlights the strategic importance of IORs in achieving sustainability goals within GVCs. On the other hand, the work of [7] shows that interpersonal relationships play a crucial role in credibility, legitimacy and trust between the actors involved in IORs . They have a significant impact on the origin, dynamics and functioning of these relationships. Thus, interpersonal relationships can act as a catalyst, inspiring individuals to work together and develop lasting collaborations. There are many success stories that highlight how IORs are a continuation of interpersonal relationships. Some lifestyle-oriented entrepreneurs build their projects on the basis of strong interpersonal relationships, building on bonds of trust and cooperation. In addition, the concept of governance, which encompasses the relations of authority and power governing the distribution and circulation of financial, material and human resources within the chain, sheds light on the dynamics of IORs [21]. These dynamics, as well as the power relations and strategies of actors within IORs, are also relevant in the agricultural context, where they can significantly influence agricultural sustainability.

In interorganizational studies, power is generally defined as “the ability of one actor to influence another to act in a way he or she would not have done otherwise” Emerson, et al., (1962, p. 32). And in our research, this is a crucial element to consider in the context of IORs. The growing importance of power in VC relationships has recently been highlighted by several scholars. Indeed, the power asymmetry between suppliers (exporters) and buyers (importers) is a well-known phenomenon among management researchers [42,11,26,56]. In these relationships, buyers are usually in a position of strength, which allows them to dictate the terms of exchange. They can exercise their power in two main areas:

a. The Strategic Area: Importers can impose their business strategy on the supplier, for example by asking it to launch new products or reduce its prices [26].

b. The Operational Domain: Importers can control the supplier’s operations, for example by imposing product specifications on the supplier or giving them instructions on how to manufacture the products. [29].

On the other hand, IORs can drive innovation in agricultural sustainability [28,25]. For example, exporters and importers can collaborate to develop new technologies and practices that help reduce the environmental impact of agriculture, Ior’s have a positive impact on agricultural sustainability by driving innovation in a number of ways. Moreover, as [32,1,52] point out, to get the most out of innovations, companies must actively involve their key partners, such as suppliers and customers, in their innovation strategies and practices. These partners, called co-innovators, are key to improving the performance of the entire CVGA.

a) +First, IORs can foster the sharing of knowledge and resources. This can be done through collaborations between organizations, training programs, or information sharing.

b) +Secondly, IORs can facilitate collaboration. This can be done through partnerships, co-development, or resource sharing.

c) +Third, IORs can provide financial support. This can be done through grants, loans, or other forms of financing. For example, governments can support IORs that promote agricultural sustainability.

In conclusion, the literature review shows that IORs can contribute to agricultural sustainability, but that these linkages are fragile and can be threatened by power asymmetry, lack of trust and divergence of interests, however sustainability could be strengthened by IORs through innovation.

Conceptual Research Model

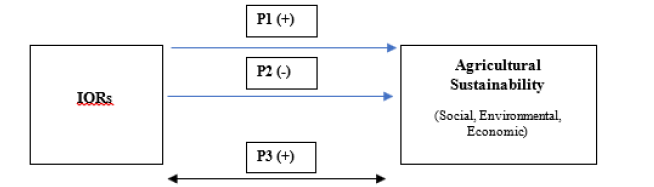

In order to obtain a global understanding of the impact of IORs on agricultural sustainability, we propose a model that integrates the different dimensions addressed in a fragmented manner in the literature (Figure 1).

Illustrates the theoretical model based on:

Figure 1: Conceptual model of the research Linkages between IORs and agricultural sustainability between two links in a VAC.

i. Power asymmetry and opportunism,

ii. Knowledge sharing and innovation, and

iii. Certification acquisition.

The figure illustrates that IORs can have both a positive and negative impact on sustainability, while highlighting that sustainability itself can be a catalyst for the development of IORs. The positive relationships between IORs and sustainability are mainly due to collaboration between organizations and the quest for innovation.

P1: Collaboration can enable organizations to share knowledge and resources, which can lead to innovations and improve sustainability.

The negative relationships between IORs and sustainability are mainly due to power asymmetry and opportunism.

P2: Power asymmetry between organizations can lead to situations where one organization exploits another, which can lead to negative consequences for sustainability. Opportunism can lead organizations to make decisions that are beneficial to them in the short term but can be detrimental to sustainability in the long term.

In a sense, IORs can influence the acquisition of certifications so that partners can work together hence the creation of sustainability.

On the other hand, sustainable organizations holding certifications, can stimulate the development of IORs. In this way, they demonstrate to potential partners their commitment to sustainability, facilitating access to new markets that are difficult to reach individually.

P3: Ior’s could positively affect agricultural sustainability and conversely sustainability can positively influence IORs through the acquisition of certifications.

Methodology

Due to the complex nature of responsible international management, particularly in the context of the Rios between France and Tunisia and considering our objective to understand the dynamics without seeking to establish cause and effect links, our research approach is qualitative Miles and Huberman (2003). We opted for an in-depth case study, recognizing that firms operating in a global environment require in-depth and contextual analysis to fully grasp their organization and operation Pettigrew, et al., (1973) [59]. We have also chosen to focus on the dyadic relationship between only two specific links: the packer-exporter and the French importer. This will allow us to analyze in detail the dynamics that occur between these two key players in the CVGA. By studying this specific relationship, we will be able to better understand the factors that influence their collaboration, their coordination over time, and their impact on the sustainability of CV as a whole. In adopting this methodological approach, we followed the recommendation of [17], who emphasized the importance of case studies in the fields of organization and management as they promote “understanding the dynamics present within unique contexts” using a variety of perspectives. This makes it possible to highlight and understand the multiple aspects of the phenomenon.

First, the choice of Tunisia as the sampling country is based on a variety of relevant factors. In fact, the outbreak of the Arab Spring in 2010 marked a period of instability in Tunisia [58]. This situation offers a unique opportunity to examine organizational dynamics in a complex and changing environment. Tunisia, being known for its date production, is the second largest export product of the country, just after olive oil. This economic specificity reinforces the importance of our study, which aims to make a significant contribution to the understanding of the long-lasting interactions within the VCs of Tunisian dates. By shedding light on the particularities of this context, we also seek to explore the influence of organizational dynamics on sustainability in this key sector of the Tunisian economy. The methodology adopted for this study, rooted in a qualitative approach, stems from the recognition of the complexity and Mult facetiousness of date cultivation in Tunisia. Guided by the work of Sinkovics, et al., (2008), we deliberately chose qualitative methods for their ability to explore in depth the complex interactions between the agricultural, environmental, social and economic dimensions of sustainability in this specific context.

The Case of Beni Ghreb

It is a widely recognized example within the industry due to its expertise in the packaging and export of dates, a presence that spans more than two decades. Founded on rigorous principles of quality and biodynamics, the company has emerged as a key player in the sector. The initiative has its roots in the biodynamic practices of producers in the Hazoua region since 1990. In 2002, they formed a Biodynamic Agriculture Development Group (GDABD). Today, the company specialises in the marketing of dates from the Hazoua region, with organic, biodynamic and fair trade certifications. Beni Ghreb is the first company certified for the production of organic and biodynamic dates in Tunisia, as well as the first to obtain fair trade certification in the world (Figure 2).

The company’s mission is to support producers and export dates to various markets such as Switzerland, Germany, France, the United States and Belgium. In addition to the Swiss partner who helped to obtain the certifications and access the first markets, other partners, including donors such as GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit) in the context of projects on resource management, have participated in the company’s growth. On the one hand, importers choose BENI GHREB because of its commitment to the economic development of the Hazua region, the quality of its dates and its numerous certifications. In addition, among these importers, BENI GHREB has two French customers. The first, Maître Prunille, a brand belonging to the cooperative group France Prune, imports dates from Algeria and Tunisia to market them in the form of dried fruit mixtures. The second customer, Mediterroir, a company founded in France by a Tunisian entrepreneur, sources BENI GHREB brand dates.

The Choice of the Single Case Selection

The choice to focus this research on a single case study stems from a deliberate intention to deepen our specific understanding of sustainability in date cultivation in Tunisia. Opting for a single, comprehensive case study allows for a comprehensive exploration of the complex interactions of this particular field, offering an in-depth dive into the details over time. Over time, many aspects can evolve and change within a company. When we conducted interviews with this company in August 2021, we got insights into where they were at that time. However, it’s important to recognize that conditions, strategies, and performance can change over the years. By going there after two years and three months, we had the opportunity to observe the changes that may have occurred. For example, the company may have implemented new sustainable practices, adopted innovative technologies, or developed new partnerships. In addition, we will be able to analyze how these changes have influenced their relationship with the other links in the CVGA.

The Beni Ghreb company, a successful model of agricultural sustainability in its three dimensions, stands out for its exceptional commitment to the subject of responsibility in the date sector in Tunisia. This company has become a reference model with its core values such as: transparency, trust, and innovation. Beni Ghreb has demonstrated collaboration with experts and researchers, and this has been illustrated by its willingness to share useful information on its ethical and sustainable agricultural practices, its ambitions and objectives and the nature of its relationships with its partners. This approach, often considered delicate and highly confidential by other companies, testifies to Beni Ghreb’s maturity and openness in its organizational practices. The decision to conduct a case study on this company was based on the fact that it provided fertile ground to understand how a real-world case works, exposing the challenges it is trying to successfully address, as well as the risks inherent in its industry. This analysis will not only dissect the internal dynamics of the company but also explore how it manages to bounce back resiliently after economic crises, thus providing valuable lessons for others in the field.

Data Collection

As part of this process, we mobilized several sources of information, the main one being the stories of executives, partners and community members. The data was collected in two phases. The first phase took place remotely (by phone/online) over a period of three months (between May-August 2021) combining semi- structured interviews and secondary data. While the second phase of collection was carried out intensively over two periods of approximately two months (September and October 2023). During the second phase, we were able to travel to Cologne, Germany for the ANUGA exhibition in which almost all the strategic players of the phoenicicultural field were present (exporters and importers) where Beni Ghreb was registered and should be present. Tunisia had a strong presence at the show for the 25th time in a row.

Organized by CEPEX “40 Tunisian exhibitors, operating in the agri-food sector and specialized in the olive oil sectors, canned food (tuna, sardines, harissa), dates and derivatives, pastries, charcuterie, pre-prepared meals, dried tomatoes, etc., are taking part in this international exhibition, through a national pavilion set up on an area of 435m²” (Digital Tunisia, 2023).

During our research, we initiated exchanges with a panel of 15 companies, mainly located in Tunisia, supplemented by representatives from Saudi Arabia, Palestine, as well as a Senegalese importer and a Franco-Tunisian importer. The list of entities with which interviews were conducted is detailed as follows in the context of our study:

a) BOUDJEBEL: 3 interviews + 2021 annual reports and other presentations in PowerPoint format

b) HORCHANI: 2 separate interviews with the two representatives

c) ROSE DU SABLE : 2 interviews

d) SOTUDEX

e) ECODATES

f) MOONDATES

g) Rift Valley (Palestine)

h) Siafa (Saudi Arabia)

i) Senegalese importer

j) French importer

k) LA ROSE DE TUNIS (Maghreb pastry/date processor)

However, we found that although their booth was carefully prepared with their latest product innovations, no Beni Ghreb official was present. This led us to question the underlying reasons for this absence and to explore the possible causes. Accompanied by the expert Hamdi M’NAWAR, we went to the South of Tunisia: to Hazoua, our second field of research. During this period, we immersed ourselves in the lives of the people working in Beni Ghreb, especially during the month of October, recognized in Tunisia as the beginning of the date harvest, a period of intense activity. We also interviewed other companies such as: BIOORIGINE, Horchani dates Sté Nouri&Co to get more information about their sustainable agricultural practices and RIOs. In total, for our Beni Ghreb case, 11 semi-structured interviews with an average duration of 90 minutes were conducted with the targeted participants. The table below provides a detailed summary of the profiles interviewed (Table 1).

Table 1: Detailed summary of the profiles interviewed.

The interview guide (Appendix 1) was designed with a view to understanding the different representations of the actors interviewed concerning agricultural sustainability (in its three dimensions), RIOs, and the link between the two concepts. However, it is important to note that the interview guide was not always strictly followed. Indeed, due to the open-ended nature of the questions, it was sometimes necessary to add more specific questions or to slightly modify the questionnaire depending on the profile of the interviewee.

Data Processing

The full transcription of most interviews was done throughout the process to facilitate quick access to information. Interviews were conducted in Tunisian, which required translation and transcription of data. Sometimes the difficulty lies in finding the word that expresses precisely the same meaning, or even the closest one, in both languages. Subsequently, a thematic analysis was undertaken, highlighting terms that are frequently used in our study.

Results and Discussion

In this section, we present the results after analyzing the interviews.

IORs

Importer-Exporter Relations:

First, the results of our research revealed that relationships with importers can have both positive and negative implications for agricultural sustainability. To begin with, it must be said that “in reality there are two types of importers”. On the one hand, the exporter describes the relationship it has with the first type of “pioneer relationship” companies that have the same objectives in terms of agricultural sustainability as Beni Ghreb. Indeed, “There are importers with whom Beni Ghreb has relations that can be described as noble who shares the same values and visions as theirs such as concern and preservation of the environment and Beni Ghreb also shares the same objectives and this guy also has the second objective which concerns socio-economic development for farmers, for the region, etc.” Thus, close relationships with importers can help farm organizations access new markets and obtain higher prices for their products. This can lead to increased incomes for farm organizations, which can allow them to invest in more sustainable farming practices. In addition, close relationships with importers can help agricultural organizations access more advanced knowledge and technologies. This can enable them to improve their farming practices and reduce their environmental impact.

On the other hand, there are the large importing organizations nicknamed “the colonizers”, who have little investment in the values and objectives of Beni Ghreb, and who seek above all to maximize their profits. With significant power within the chain, they are willing to blackmail exporters, thus imposing more restrictive financial conditions in order to obtain reduced prices for a good quality product. “The big companies impose their power on us, and the other organizations that are certified and respect the ecological product, it’s a give-and-take, while the big companies are the opposite. Big corporations are blackmailing us.” The exporter explains that the LEs “Before she comes to work with us, they go around to 50 other exporters. You, as an exporter, before you buy a product, you will need pre-financing, and in the event that this organization, this large company, is going to give you the pre-financing, you have to condescend. For example, you have to lower the price.”

This power asymmetry highlights the challenges faced by exporters, who often have to strike a delicate balance between preserving their margins as well as their customers and maintaining stable business relationships with these large importing organizations. In summary, Beni Ghreb makes a clear distinction between these two types of foreign importers by focusing on the words frequently used in their discourses such as: “respect”, “trust”, “opportunism”, the situation and the fragile period that it is trying to overcome “in need”. The Tunisian exporter says that: “To be honest, there are several companies that respect the producer, they also respect the organization that supplies him with the final product. When you give them a fair price, just for yourself, for the worker and for the farmer from whom you have taken the goods, he respects, he respects. And on the other hand, as we said before, there are other large organizations that unfortunately do not comply, ask to give them the certificate and a minimum price, adding to this that they ask you to provide them with 20 to 30 containers, 400 tons, 300 tons, 500 tons, and we are somehow forcing you to lower the prices.”

We’ve touched on day-to-day topics, but now let’s focus our discussion on a crucial period: the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis. This phase has led to significant global upheaval, leaving a significant footprint on various sectors, including agri-food companies and manufacturing. Beni Ghreb, as a player at the heart of these transformations, has faced unprecedented challenges, adjusting its strategies and operations to adapt to an ever-changing environment. Beni Ghreb had a negative experience with GE importing dates. Indeed, the interviewee shares this experience with us with sadness: “I will now tell you about a case of a large company with which, unfortunately, I worked for 5 years, and finally they asked... They put pressure on us, and they made the choice to stop our collaboration on the condition that we give them exclusivity on the list of our customers in their entire country... In other words, it means that we will no longer have the right to sell to importers in that country, except for this large organization, and they are the ones who are in charge of distribution throughout the country. This means that they want us to sell our products only and exclusively for them.” As we can see from these excerpts of speeches, the opportunism shown by some large companies during periods of vulnerability, such as the COVID-19 crisis, raises major concerns. These practices, which include unfavourable contractual terms and harmful strategies, add to the other challenges faced by SMEs. In the case of this SME, faced with a delicate situation and having no viable alternative, it is forced to accept the conditions imposed by its foreign partner. The risk of losing its contract with the latter thus gives this partner greater power over the SME.

When Beni Ghreb “accepted this request, they said, no, we (the foreign partner) don’t want it anymore, they (the foreign partners) forced us to cut off our relations with all of Europe, and we have to go only through them for the sale of our products. They saw me in need, especially in the post-COVID crisis.” In a desire for expansion, the foreign partner expresses the desire to obtain Beni Ghreb’s customer contacts, not only on the national territory, but throughout Europe. In other words, he wants Beni Ghreb to share his entire customer base, while he himself would remain the company’s only preferred customer. Finding itself in a delicate financial situation, the Tunisian exporter agreed to grant extensive access to its customer information as part of its collaboration with the foreign partner. However, in an attempt to preserve some autonomy and protect its existing relationships, Beni Ghreb has issued the request to retain access to its former clients “because, God forbid, in case they have broken a contract after five years, or 6 years in exclusivity, I will not have any clients and I will have given up all these clients”. Faced with this asymmetry of power, Tunisian exporters are forced to accept the control of importers. This can have a negative impact on their performance, as they lose some of their decision-making autonomy.

To limit the impact of power asymmetry, suppliers can adopt different strategies, such as:

i. Develop a relationship of trust with the importer: A relationship of trust can allow the supplier to gain some leeway in negotiations [58].

ii. Diversify your customer base: by selling its products to several importers, the supplier reduces its dependence on a single importer [54].

iii. Develop your own brands: By developing its own brands, the supplier can evade the control of the importer [26].

Managing power asymmetry therefore presents a major challenge for exporters.

Thus, this concrete example offers us a light on the challenges that companies face in complex situations. In fact, the need to maintain financial stability has led the company to make complex strategic decisions, balancing economic imperatives with its commitment to sustainability.

Competing Importers

We now turn to our second result, namely the relations between Tunisian importers. To shed light on the history of Beni Ghreb, it is necessary to highlight its fundamentally family nature. This family structure is not limited to administrative simplification, it is the very essence of the company. The story of Beni Ghreb is presented as a family saga, imbued with the continuity of generations and the transmission of a precious heritage. Indeed, it is above all through these foundations that the company is guided in its unwavering commitment to quality, sustainability and ethics. Rooted in strong family ties, Beni Ghreb draws strength from this tradition, shaping her identity and her exceptional journey. The interviewee presents the story: “our small group developed from nine farmers to some fifty farmers who have a family aspect, that is to say the family of SAIDI here, even the name of the company Beni Ghreb, it is a ... of the family here who have been nomads between Kebili and Tozeur on the edge of the Tunisian-Algerian border, for years, years who have created oases here after colonization since 1958 exactly.” In fact, Beni Ghreb literally means “Son of the Stranger” in Arabic, and this is the name given at the time to this nomadic family, Bedouins between Kebili and Tozeur who moved according to their grazing needs [18,22,34].

The continuous use of the name “Beni Ghreb” to this day testifies to the importance of family connection and underlines the durability of the values transmitted through the generations. This continuity is part of a company that, over time, has been able to develop a solid and well-organized structure, thus demonstrating its ability to evolve while preserving the family foundations that have forged its identity. In difficult times, the company can count on the support of those close to it, especially its family. Moreover, the company had a lot of financial problems after COVID-19, and “praise be to God, we (Beni Ghreb) took back all our customers, but not totally because now Tunisian banks cannot lend money as long as you already have unpaid bills, forbidden to checkbook, while you have losses, when you have lawsuits because you have cheques that you didn’t pay on time.” And in order to overcome the situation, Beni Ghreb was able to count on the essential support of his relatives, especially the brothers and sisters, who “generously provided about 430 tons of dates from their harvest” and the “client companies that respect our organization” for example “he gives me an advance of 30% of the turnover when we go together, That’s how he can give more or he can give less, and it will depend on the degree of intensity of our relationship with him”[40,43].

In this region, a few companies, although supposed to be competitors in the market, take a collaborative approach, especially in difficult times. This spirit of generosity, transparency and cooperation characterises the local entrepreneurial fabric. According to Beni Ghreb, BIOORIGIN and Nouri&Co these companies maintain partnership relationships based on respect and trust. This collaboration is mutually beneficial, allowing these few companies to support each other in the event of difficulties, whether through “sharing goods, packaging or other necessary resources”. This collective approach not only contributes to solidarity within the small entrepreneurial community, but also helps to reduce costs and improve the overall competitiveness of these companies. This clearly demonstrates that there is strength in numbers. Regarding other competing companies in southern Tunisia, there is practically nothing to discuss, perhaps due to a lack of significant relations between them.

Sustainability and Certifications: The Challenge of the Century

Since its creation, it has positioned itself as a pioneering company committed to a sustainable approach. Its history is closely linked to the values of environmental preservation, social responsibility and ethics. This family business has left its mark on its territory by being among the first in Tunisia to undertake certifications attesting to its sustainable practices. Indeed, Beni Ghreb stands out from other Tunisian exporters as a pioneer, being the first in Tunisia to obtain organic and biodynamic certifications for their dates, and also the first in the world to be certified for fair trade. The dates of this company have been certified since 1992 before the creation of the Tunisian law 30-99 since 1999 relating to the organization of biodynamic agriculture. Thus, this initiative has its origins in the biodynamic practices adopted by producers in the Hazoua region since 1990. “These are objectives that allow us to preserve the environment and have a rhythm of life with which we can preserve what we currently have, preserve the soil, the atmosphere, etc. For future generations, just as our grandfathers and great-grandfathers taught us.” Beni Ghreb has obtained several certificates reinforcing its commitment to quality and sustainability. The certifications include the organic label, biosuisse, demeter, fair trade, NOP for USDA organic, this is the part of the production certified with our group and also we have the ISO 22000 and ISO 9001 certificate and partially we do the set-up for the IFS and the IPRC to integrate and find a place with the other importers who are asking for more of the requirements currently for process certification. from... of the process, at the level of the transformation.”

Thanks to these prestigious certifications, Beni Ghreb can demonstrate its agricultural sustainability through its three dimensions: environmental, social and economic. These labels reinforce our commitment to ethical agricultural practices, the preservation of the environment, and the well-being of local communities. By meeting the stringent requirements of foreign partners, the exporter is able to satisfy increasingly demanding consumers, while gaining access to markets with high barriers to entry. These certifications are thus a guarantee of its commitment to sustainability and a way to conquer demanding international markets. However, although the certification process is often complex, Beni Ghreb is fully capable of meeting the multiple requirements involved in these standards. The company actively engages in every step of the certification process, demonstrating its ability to meet the strict criteria associated with these labels. Beni Ghreb’s determination to meet these high standards is particularly essential, as some major Tunisian date importing companies impose a binding requirement to obtain these certifications. These partners consider these standards to be essential criteria in the choice of their sales employees. “Currently, (in 2021) we are doing the implementation of IFS and BRCs, as I explained to you, it is a requirement of our customers despite the fact that it requires a rigorous infrastructure with a large budget also to ensure the safety of the food fertilizers of our product”.

Therefore, to maintain fruitful relationships with these major players in the market, Beni Ghreb considers the acquisition of these certifications as a necessity, thus strengthening its position and credibility within the date industry. The certifications obtained by Beni Ghreb are not only limited to the environmental aspect of sustainability, and the guarantee of optimal quality, but they also encompass the socio-economic well-being of local actors, thus positively impacting the living conditions of farmers and the development of the Hazua region. Closely linked to its member farmers, Beni Ghreb is fully committed to improving the working conditions of its employees. In this context, the manager of Beni Ghreb conducted an in-depth study on the living conditions of the date producer in Tunisia. Through this study, the manager wants to know how the producer could “live in modest conditions throughout the year, because the palm tree gives us only one harvest per year”. And as a result, the latter found that this sustainable business “provides producers with 80% of the subsistence requirements” for the organic date grower, however, “conventional ones don’t even provide the 40, 50%”. This is justified by the fact that the company “does organic and it’s a little more expensive and we buy biodynamic, we also give bonuses to and we collaborate together because in the end if we (they) want to respect the consumer, and the latter consumes something beneficial, and of quality, The producer must be well paid so that he can provide a quality product, and the same is true for the worker.” Indeed, in the event that they exert “a force (of price reduction) on the producer, the latter will not stay with us (them) but will go elsewhere in another oasis, so he will look for other resources so that he can live”.

In this context, we can give the example of the fair trade label to illustrate, and this serves as a guarantee for farmers’ rights by ensuring “a remuneration of about 15 cents per kilogram, thus going directly to small farmers in the form of donations”. In summary, Beni Ghreb’s in-depth analysis reveals the richness and diversity of its commitments to sustainability, ethics and quality. Through rigorous certifications, the company demonstrates its concern for the environment, the socio-economic well-being of its farmers and the development of the Hazoua region. Although innovation was not explicitly discussed in this study, it remains a key pillar of the company, manifesting itself in continuous improvements in its products, processes and partnership with market players. Although our research proposals have been successfully validated, we acknowledge that our study, which focuses on VC management in date production in Tunisia, does not address some crucial aspects of the sector. In particular, dimensions such as technological innovation, environmental advances, and other technical aspects remain underexplored in our research. For the sake of brevity and time constraints, our study was limited in its exploration of the complex facets of the VC of Tunisian dates. Lack of resources and time has limited our ability to address crucial aspects such as technological and environmental innovation, as well as other technical areas. We fully recognize that this study can be seen as a first step and paves the way for furthermore in-depth and diverse research. The dynamic whole of the date value chain in Tunisia offers many opportunities for further investigations that would contribute to a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of responsible management and sustainability in this specific sector.

Conclusion

Responsible management of CVG is a complex and multidimensional field. He is interested in how organizations can manage their activities in a way that maximizes their positive impacts and minimizes their negative impacts on the economic, social and environmental dimensions. Responsible VC management is an imperative in the contemporary business landscape, especially in the face of the complexity of interconnected relationships in specific sectors such as the Tunisian date industry. In fact, the case study of the Tunisian date industry illustrates the complexity of this field. The sector is made up of a multitude of actors, each with its own interests and objectives. The relations between these actors are often complex and based on trust, and at the same time, this sector is characterized by an asymmetry of power, given that foreign importers generally have significant power over Tunisian producers and exporters. To conclude, we can say that the Beni Ghreb case study offers us a comprehensive overview of a company that, through its integrity, commitment and spirit of innovation, positions itself as a major and exemplary player in the date industry [51,56].

References

- Acar Y Atadeniz SN (2015) Comparison of integrated and local planning approaches for the supply network of a globally dispersed enterprise. International Journal of Production Economics 167: 204-219.

- Agostini L, Filippini R (2019) Organizational and managerial challenges in the path toward Industry 4.0. European journal of innovation management 22(3): 406-421.

- Apenuvor KD (2011) Rapports de pouvoir et stratégies d'acteurs dans les relations interorganisationnelles Nord-Sud. Etude de cas: les partenariats de Brücke Le pont (Suisse), EED et Pain pour le Monde (Allemagne) avec les ONG togolaises (Doctoral dissertation, Université de Franche-Comté).

- Bansal P, DesJardine MR (2014) Business sustainability: It is about time. Strategic organization 12(1): 70-78.

- Bertotto B, Pohlmann M, Silva F (2014) The dimensions of sustainability: concepts and strategies in the textile and clothing supply chain in Brazil. KES Transactions on Sustainable Design and Manufacturing, Sustainable Design and Manufacturing. Paper sdm14-029: 218-229.

- Brundtland GH (1987) What is sustainable development. Our common future 8(9).

- Chabaud D (2009) Les relations interorganisationnelles des PME, Katherine Gundolf et Annabelle Jaouen (dir.), Paris, Hermès-Lavoisier, 2008, 322 p. Revue internationale PME Économie et gestion de la petite et moyenne entreprise 22(2): 173-177.

- Chaddad F, Rodriguez-Alcalá, ME (2010) Inter-organizational relationships in agri-food systems: a transaction cost economics approach. In Agri-food chain relationships (pp. 45-60). Wallingford UK: CABI.

- Chauhan C, Kaur P, Arrawatia R, Ractham P, Dhir A (2022) Supply chain collaboration and sustainable development goals (SDGs). Teamwork makes achieving SDGs dream work. Journal of Business Research 147: 290-307.

- Chichilnisky G (2011) What is sustainability?. International Journal of Sustainable Economy 3(2): 125-140.

- Chicksand D (2015) Partnerships: The role that power plays in shaping collaborative buyer–supplier exchanges. Industrial marketing management 48: 121-139.

- Cropper S, Ebers M, Huxham C, Ring PS (2008) Introducing Inter‐organizational Relations. In The Oxford Handbook of Inter-Organizational Relations. Oxford University Press 3-22.

- De Lange DE, Busch T, Delgado-Ceballos J (2012) Sustaining sustainability in organizations. Journal of business ethics 110: 151-156.

- Douard JP, Heitz M (2003) Une lecture des réseaux d'entreprises: prise en compte des formes et des é Revue française de gestion 5: 23-41.

- Du Pisani JA (2006) Sustainable development–historical roots of the concept. Environmental sciences 3(2): 83-96.

- Dubois JL Mahieu FR (2002) "La dimension sociale du développement durable : lutte contre la pauvreté ou durabilité sociale ?" in J-Y.Martin (Ed.), Développement durable ? Doctrines, pratiques, évaluations, IRD, Paris, pp.73 –94.

- Eisenhardt KM (1989) Building theories from case study research. Academy of management review 14(4): 532-550.

- Emerson RM (1964) Power-dependence relations: Two experiments. Sociometry 282-298.

- Forgues B, Fréchet M, Josserand E (2006) Relations interorganisationnelles. Conceptualisation, résultats et voies de recherche. Revue française de gestion 32(164): 17-32.

- Fritz, Melanie, Gerhard Schiefer (2008) Sustainability in food networks 865-2016-60482.

- Gereffi G (1994) The organization of buyer-driven global commodity chains: How US retailers shape overseas production networks. Commodity chains and global capitalism 95-122.

- Gereffi G, Korzeniewicz M (Eds.) (1993) Commodity chains and global capitalism. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Giovannoni E, Fabietti G (2013) What is sustainability? A review of the concept and its applications. Integrated reporting: Concepts and cases that redefine corporate accountability 21-40.

- Gunasekaran A, Subramanian N, Rahman S (2015) Green supply chain collaboration and incentives: Current trends and future directions. Transportation research part E: logistics and Transportation Review 74: 1-10.

- Guo Y, Yen DA, Geng R, Azar G (2021) Drivers of green cooperation between Chinese manufacturers and their customers: An empirical analysis. Industrial Marketing Management.

- Hingley M, Angell R, Lindgreen A (2015) The current situation and future conceptualization of power in industrial markets. Industrial Marketing Management 48: 226-230.

- Hobbs JE, Young LM (2000) Closer vertical co‐ordination in agri‐food supply chains: a conceptual framework and some preliminary evidence. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 5(3): 131-143.

- Hong J, Zheng R, Deng H, Zhou Y (2019) Green supply chain collaborative innovation, absorptive capacity and innovation performance: Evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production.

- Johnsen RE, Ford D (2008) Exploring the concept of asymmetry: A typology for analysing customer–supplier relationships. Industrial marketing management37(4): 471-483.

- Kidd CV (1992) The evolution of sustainability. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 5: 1-26.

- Koubaa S (2008) La coopération interorganisationnelle et l'innovation en PME: une analyse par le concept de la capacité d'absorption des connaissances (Doctoral dissertation, Thèse de doctorat en Science du Management, Université de Mohammed Premier, 9 février).

- Krishnan R, Yen P, Agarwal R, Arshinder K, Bajada C (2021) Collaborative innovation and sustainability in the food supply chain- evidence from farmer producer organisations. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 168.

- LAMBERT A (2001) La désintégration verticale : une réponse aux exigences de flexibilité dans les industries alimentaires, Gestion 2001, janvier février: 48-62.

- Li Q, Kang Y, Tan L, Chen B (2020) Modeling formation and operation of collaborative green innovation between manufacturer and supplier: A game theory approach. Sustainability (Switzerland).

- Lock I, Seele P (2017) Theorizing stakeholders of sustainability in the digital age. Sustainability Science 12(2): 235-245.

- Loconto AM, Santacoloma P, Rodríguez RA, Vandecandelaere E, Tartanac F (2019) Sustainability along all value chains: exploring value chain interactions in sustainable food systems. In Sustainable diets: linking nutrition and food systems 215-224.

- Meadows DH, Meadows DL, Randers J, Behrens III WW (1972) The limits to growth-club of rome.

- Mehdikhani R, Valmohammadi C (2019) Strategic collaboration and sustainable supply chain management: The mediating role of internal and external knowledge sharing. Journal of Enterprise Information Management 32(5): 778-806.

- Mikhailitchenko A, Lundstrom WJ (2006) Inter‐organizational relationship strategies and management styles in SMEs: The US‐China‐Russia study. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 27(6): 428-448.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM (1984) Drawing valid meaning from qualitative data: Toward a shared craft. Educational researcher 13(5): 20-30.

- Nyaga GN, Whipple JM (2011) Relationship quality and performance outcomes: Achieving a sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of business logistics 32(4): 345-360.

- Nyaga GN, Lynch DF, Marshall D, Ambrose E (2013) Power asymmetry, adaptation and collaboration in dyadic relationships involving a powerful partner. Journal of supply chain management 49(3): 42-65.

- Pettigrew AM (1985) Contextualist research and the study of organizational change processes. Research methods in information systems 1(1985): 53-78.

- Pohlmann CR, Scavarda AJ, Alves MB, Korzenowski AL (2020) The role of the focal company in sustainable development goals: A Brazilian food poultry supply chain case study. Journal of Cleaner Production 245: 118798.

- Renko S (2011) Vertical collaboration in the supply chain. In Supply Chain Management-New Perspectives. Intech Open.

- Rong L, Xu M (2020) Impact of revenue-sharing contracts on green supply chain in manufacturing industry. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 13(4): 316-326.

- Rosen MA (2018) Issues, concepts and applications for sustainability. Glocalism: Journal of Culture, Politics and Innovation 3: 1-21.

- Royer A, Bijman J (2012) Towards an analytical framework linking institutions and quality: Evidence from the Beninese pineapple sector. Afr J Agric Res 7(38): 5344-5356

- Sedziniauskiene R, Sekliuckiene J, Zucchella A (2019) Network’s impact on entrepreneurial internationalization: A literature review and research agenda. Management International Review 59(5): 779- 823.

- SINGH DA (2009) Export performance of emerging market firms. Int. Bus. Rev (18): 321- 330.

- Sinkovics RR, Penz E, Ghauri PN (2008) Enhancing the trustworthiness of qualitative research in international business. Management international review 48: 689-714.

- Storer M, Hyland P, Ferrer M, Santa R, Griffiths A (2014) Strategic supply chain management factors influencing agribusiness innovation utilization. The International Journal of Logistics Management 25(3): 487-521.

- Svensson G (2007) Aspects of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM): conceptual framework and empirical example. Supply chain management: An international journal 12(4): 262-266.

- Talay C, Oxborrow L, Brindley C (2018) An exploration of power asymmetry in the apparel industry in the UK and Turkey. Industrial Marketing Management 74: 162-174.

- Talay C, Oxborrow L, Brindley C (2020) How small suppliers deal with the buyer power in asymmetric relationships within the sustainable fashion supply chain. Journal of Business Research 117: 604-614.

- Talay C, Oxborrow L, Goworek H (2022) The impact of asymmetric supply chain relationships on sustainable product development in the fashion and textiles industry. Journal of Business Research 152: 326-335.

- Valiorgue B (2023) La durabilité agricole, ou l'enjeu du siè In Le Déméter 2023 (pp. 25-38). IRIS éditions.

- World Bank, 2014. Rapport annuel 2014 de la Banque mondiale.© Washington, DC.

- Yin RK (2003) Designing case studies. Qualitative research methods 5(14): 359-386.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.