Case Report

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Elderberry (Sambucus nigra) Lectins in Gastrointestinal Ailments and a Preparation for the Treatment of Upper Respiratory Throat Disorders

*Corresponding author: Ian F Pryme, University of Bergen, Department of Biomedicine, University of Bergen, Jonas Liesvei 91, 5009 Bergen, Norway.

Received: May 31, 2024; Published: June 07, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.22.003012

Abstract

It is to Theophrastus (287-370 BC) that we owe the classical theories on the medicinal uses of wild plants, and it is also well known that Dioscorides (40-90 AD) had studied, recognized, and classified more than 500 wild plants that had effects on several different illnesses of the human body. The ancient Greeks used elderberry preparations as a remedy for a series of stomach complaints including stomach-ache and heartburn. It is thus evident that elderberry has a history of more than 2000 years in traditional folk medicine. Researchers in both Switzerland and Italy have found evidence that elderberry can have been grown many centuries ago because of its medicinal properties. Furthermore, a description of the preparation of elderberry extracts, as a basis for treatment of a whole series of ailments, has been found as far back as in ancient Egypt. Unfortunately, the actual method used for extract preparation has been quite different from laboratory to laboratory.

Introduction

The common name elder is derived from the Anglo-Saxon word æld, meaning “fire”, since blowing through the hollow stems of the young branches was a method for building up fires. Elder was often referred to as the “medicine chest of the country people” and has a history of traditional use among Native Americans and herbalists of Europe [1]. There is a wealth of European folklore associating the plant with life-enhancing effects such as increased longevity and vigor. Much of the traditional use of elder and modern research has focused on the flower, not the bark or fruit. References to the berry, however, can be found in many pharmacopeias over the centuries, including the Italian, Dutch, Portuguese, Croat Slovak, German, Austrian, Swiss and Hungarian. The medicinal uses of the elderberry are almost as numerous as those who reported them: Johann Bauhin (1541-1613) mentions their use by peasants for dysentery and diarrhea; Adam Lonicer (1528-1586) and Johann von Muralt (1638-1733) describe their use for inducing perspiration to remove toxins, and Conrad von Megenberg (1309-1374) first mentioned elderberry juice to increase resistance to illness. Agustí (1617) has documented that in Catalonia, elderberry preparations have been used for centuries for the treatment of a series of ailments. The berries are regularly incorporated into food and condiments for colouring and flavour. They have long been used for making preserves, wines, winter cordials, and for “adulterating,” i.e. adding flavour and colour to other wines. Most of the elderberries used commercially are imported from Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Portugal and the Russian Federation. About 10,000 tons of elderberry are used in Austria for making beers, jellies, wines and winter cordial drinks.

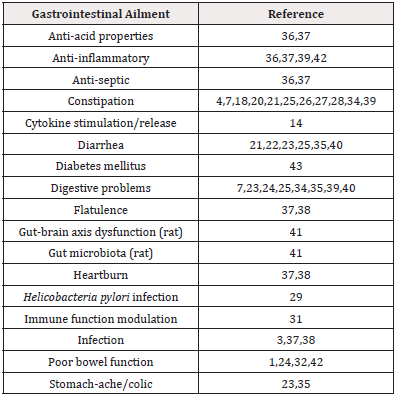

In folk medicine, elderberries have been used for their diaphoretic, laxative and diuretic properties and to treat various ailments such as stomach-ache, sinus congestion, constipation, diarrhea, sore throat, common cold, and rheumatism [2-8]. The flowers are said to have diaphoretic, anti-catarrhal, expectorant, circulatory stimulant, diuretic and topical anti-inflammatory actions [5]. Some of these properties seem justified since elderberry fruits contain tannins and viburnic acid [8], both known to have a positive effect on diarrhea, nasal congestion, and to improve respiration. Leaves and inner bark have also been used for their purgative, emetic, diuretic, laxative, topical emollient, expectorant, and diaphoretic actions. More than 300 lectins have now been identified in vegetables, fruits, cereals, seeds, nuts, flowers, herbs and spices [9] (Table 1).

Note*: 1-3 Indicates the order of abundancy.

Sambucus nigra has probably been grown in Norway since the early Middle-Ages, brought to the country by the monks. Even today it is widely found as a medicinal as well as an ornamental plant. It was used for treatment of gastrointestinal, urological as well as gynecological problems [5]. The flower has played a dominant role in modern Norwegian folk medicine. In Norwegian household’s elderberry juice and/or wine from berries, has been used as an agent for treatment of gout and as a stomach-regulating agent with a mild laxative effect. In the Norwegian Wikipedia we find reference to the lectins from both elderberry and mistletoe [9-11] as being of interest for the immune system. Mistletoe lectins have been closely linked in the fight against cancer [11].

Bioactive Constituents Present in Elderberry Juice

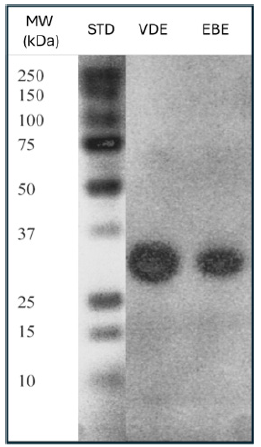

The fruits of elderberry have many well-characterized active constituents, including flavonoids (e.g. quercetin and rutin), anthocyanins (e.g. cyanidin-3-glucoside and cyanidin-3-sambubioside), cyanogenic glycosides, including sambunigrin, viburnic acid, and vitamins A and C [8,9]. With respect to macromolecular components three lectins have been characterized and studied in the fruit : SNA 1f (4x60 kDa subunits), SNA IVf (2x32 kDa subunits) and SNA Vf (4x30 kDa subunits), showing specificity for 3-linked sialic acid, GalNAc and GalNAc, respectively (Table 1). Based on this it was decided that VDE would be the best extract to be used for column chromatography. The product obtained has been termed PALS (Preparation enriched in lectins from Sambucus nigra). That elderberry contains 30 and 60 kDa subunits (Figure 1), where the 30 kDa protein is the most abundant, has been demonstrated [11,12]. The richest protein in the fruit is the lectin SNA-1Vf which is derived from a truncated type 2 ribosome-inactivating protein (Figure 1).

Another lectin is present in seeds-SNA III (2x60kDa), showing specificity for GalNAc [8]. Because of their extensive pattern of glycosylation and globular nature most lectins pass through the gastrointestinal tract in an intact form [9]. The lectins can bind to receptors in Peyer´s patches (see below) and they exhibit immunostimulatory properties. It has been shown that there is about 10mg/ kg of lectins in raw fruit [13]. The pharmacokinetics of many of the bioactive constituents, however, is not yet completely understood. Research has, for example, focused on absorption and urinary excretion of the anthocyanins, which are absorbed and excreted intact, without first being hydrolyzed in the gastrointestinal tract. Vlachojannis, et al., [4], Atkinson and Atkinson [6], Lim [7], Pryme and Dale [8], Pryme and Aarra [9] all describe in depth the current state of knowledge with respect to the biochemical composition of Sambucus nigra, including lectin content.

Binding of Elderberry Lectin to Cells of Peyer´s Patches in the Human Small Intestine

Sharma, et al., [14] studied the binding of a series of lectins to various cell types associated with Peyer´s patches in human small intestine biopsy material. Elderberry lectin (SNA-II, found in the bark) was seen to bind to M-cells, enterocytes and goblet cells of the follicle-associated epithelium, to goblet cells of the villus epithelium and to macrophages of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. The significance of these differences in binding properties is not known. It is, however, known that lectins bind to the surface of cells bearing appropriate receptors and this sets off a cascade of intracellular events leading to a lectin-specific biological response resulting in the release of e.g., cytokines, growth factors, hormones, enzymes. Barak, et al., [15] have demonstrated that an elderberry-based natural product is able to stimulate the release of cytokines in humans. A systemic response is thus expected following the ingestion of a lectin-containing elderberry preparation. The presence of a series of components exhibiting immuno-modulatory properties in extracts of berries and flowers from Sambucus nigra L. has now been demonstrated [16]. Aricigil and Pryme [17] have discussed a model suggesting how dietary lectins can result in a biological response following their binding to receptors in the small intestine.

Figure 1: A lectin-enriched preparation from Sambucus nigra was prepared as described by Eifler, et al., [12], and termed EBE (Eifler Berry Extract). EBE was run on a gel according to [13] and compared to VDE (Van Damme Extract). The results were such that the method described for the preparation of VDE was judged as being appropriate, and was later termed PALS (Preparation enriched in lectins from Sambucus nigra).

Antibacterial Activity Against Hospital Pathogens

Hearst, et al., [18] have reported the presence of components in elderberry flower and berry preparations that exhibit strong antimicrobial effects on various nosocomial pathogens, notably Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (CA-MRSA), recognized globally as a clinically significant pathogen. A lectin-containing fraction was shown to contain potent inhibitors of microbial cell metabolism, including effects on transcription in vitro, thus targeting bacterial RNA synthesis.

The Development of a Lectin-Enriched Elderberry Preparation

There are observations on file that are completely in line with the historical, long-term use of elderberry-based preparations as an effective remedy against diverse gastrointestinal problems. Initially a lectin-enriched elderberry preparation aimed at causing immune stimulation i.e. as an effective agent against colds and flu was produced. An effective immuno-stimulation was attributed to the high lectin content of the preparation. After about 2 years of use by >40 individuals, very interesting feedback was obtained; not only did the respondents report less susceptibility to colds and flu but surprisingly 80% of the individuals also indicated improvement in gastrointestinal function. This prompted a literature search and, as indicated below, this revealed that elderberry had indeed a long history of use in folk medicine as an effective agent for the alleviation of diverse stomach and intestinal problems. Based on these observations they developed a product which is now commercially available. This elderberry preparation, in tablet form, has proved to be of great assistance to many people that have often suffered in the long term from one, or more, of a wide variety of gastrointestinal ailments (unpublished observations). The majority had not experienced relief from other preparations currently available on the market.

Clinical Studies

Clinical studies have not been performed on a common gastrointestinal problem such as constipation, where the laxative properties of elderberry would have been investigated. The reasons for this are many. A case of “ordinary constipation” is readily diagnosed by the individual affected and is often ”short-lived” not requiring consultation with a physician. This would mean, therefore, that if one attempted to enroll patients into a study then inevitably many would be symptom-free at the commencement of the study, or at least would have already embarked on some form of treatment. One would need to know the underlying reason for their constipation to be able to assemble a group of homogeneous individuals for a study. This is practically impossible. Furthermore, prediction of the occurrence of constipation is out of the question. Most ordinary cases of constipation are relatively “short-lived”, while long-term constipation is often a result of bowel occlusion as for example, in colon cancer, requiring immediate intervention (most often surgery). Although there is a lack of clinical studies regarding elderberry as a laxative, for the reasons given here, there is a wealth of evidence in the literature clearly showing that for centuries there has been a traditional use of elderberry as a laxative in many European countries. The use of elderberry as a laxative to relieve constipation is referred to widely in the scientific literature as is its use in the relief of several other common gastrointestinal problems (Table 2). At the present time, however, we are unfortunately unable to provide a satisfactory scientific basis enabling us to explain these effects (Table 2).

Note*: Where authors have indicated the existence of, for instance,”Digestive problems”, ”Poor bowel function” or ”Diverse gastrointestinal problems” these may include symptoms such as e.g. ”Stomach Ache”, ” Heartburn” or ”Flatulence”, but these are not individually mentioned.

It is clear that the gastrointestinal tract is so complicated that individual variation will be wide. A host of factors will inevitably play major roles in governing its function, among these are : age, gender, genetics, diet, body weight, fluid intake, smoking and drinking habits, bacterial/yeast flora, general hormone balance including hormones regulating gastrointestinal function, psychological status, medical history of gastrointestinal problems (individual, and/or familial), status regarding gastrointestinal regulatory mechanisms (biochemistry, morphology, nerve system, tension, stress, emotions etc.), level of HCl production by the stomach, composition of the bile and digestive juices, short-term or long-term use of medication that may have (or had) side-effects affecting gastrointestinal function. It is also highly likely that many of these factors (more than 20) can exert either positive or negative effects upon one another making the situation extremely complicated. It is thus not surprising that a remedy for one gastrointestinal problem, successful for one person, may not necessarily be effective for another individual experiencing a similar problem in their gastrointestinal tract. Various elderberry preparations have been utilized in Asia, Europe and the USA for centuries. One of the uses in traditional folk medicine has been in the treatment of a number of gastrointestinal disorders. Unfortunately, how a positive response is effectuated is not yet properly understood. It is highly likely that the following known properties of elderberry components are implicated: immunomodulatory action (local/systemic), anti-bacterial and anti-viral effects, a positive biological response following binding of lectins to specific receptors, complex formation between certain types of bacteria and lectins.

Treatment of Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Despite the lack of clinical studies concerning elderberry there are many reports in the literature where different preparations have been used. Here, these have not been considered. Novelli, [19] states that elderberry has been used as an effective agent in the treatment of constipation, and in a monograph from 2005 we read that elderberry has been used in traditional medicine as a laxative [20]. Cejpek, et al., [21] report that elderberries have a laxative effect when administered in small doses while both Uncini Manganelli, et al., [22] and Merica, et al., [23] indicate the use of elderberry in the management of diarrhea. Henneberg and Stasiulewic [24] have provided an in-depth overview of the use of a series of plants in Folk Medicine in Lithuania. Elderberry has been in general use for several generations as an effective treatment for a series of stomach ailments including diarrhea and general forms of stomach-ache. According to Urtekildens leksikon (3.1; in Norwegian) elderberry is classified as having the properties of acting as a laxative, and, interestingly, has the property of strengthening capillary walls, particularly in the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract. Holistic online (http://www.holistic-online.com/Herbal-Med/_Herbs/h51.htm) has a chapter entitled “Herbal Medicine”, where it is indicated that elderberry preparations are effective in treating diarrhea. In southern Italy, a decoction made by boiling fresh elderberries in water is a folk remedy for stimulating bowel function. Madaus [25] states that a decoction of dried elderberries has been in long-term use as a laxative in Germany, and that a tea prepared from fresh elderberries has been put to the same use since 1887 in the Ukraine, Poland and Czechoslovakia. According to Grieve [26] an elderberry syrup (Roob Sambuci) has been employed as a laxative in Britain [with reference to the British Pharmacopoeia (1788)]. Both Karmazin, et al., [27] and Wichtl [28] [with reference to Swiss Pharmacopoeia V. edition (1953)] comment on the traditional use of elderberry as a laxative.

Vlachojannis, et al., [4] have written a systematic review on the Sambuci fructus, effect and efficacy profiles. In the Introduction p.1 we read: “The dried ripe or fresh berries of Sambucus nigra L are used in traditional German medicine for the treatment of constipation, to increase diuresis, as a diaphoretic in upper respiratory tract infections, for the alleviation of low back and/or neuropathic pain, headache and toothache”. For treatment of these complaints, patients consume elderberry juice, or they drink a cup of tea (aqueous extract) several times per day. The infusion is prepared from 10 g dried berries standing in cold water for several minutes, then slowly heated up, and briefly boiled. Before filtering, a drawing-time of 5 to 10 min is recommended. About 50% of the world´s population is infected with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). This bacterium is implicated in the etiology of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer and ventricle cancer. Chatterjee, et al., [29] has studied the inhibition of growth of H. pylori in vitro by various berry extracts, including elderberry, and susceptibility to the antibiotic clarithromycin. Resistance to antibiotics such as clarithromycin is a major problem and an interest in developing alternatives/adjuncts to therapy has been stimulated. The authors showed that a 1% concentration of elderberry extract was sufficient to cause 90% inhibition of bacterial growth and that the effect was attenuated up to 100% by clarithromycin [29]. This study demonstrates the powerful potential of using the antibacterial activity of berry extracts alone, or in combination with an antibiotic drug, against the growth of H. pylori, to alleviate gastrointestinal problems caused by infection with the bacteria. That dietary lectins influence gastrointestinal and immunological function has been summarized by Cordain, et al., in their review [30].

In the book “The Anatomy of elder” [5] the use of elderberry on different indications is discussed. Two chapters of special interest are Chapter 19 “Of affections of the Stomach” and Chapter 20 “Affections of the Intestine” showing the traditional use of elderberry on these indications. These two chapters connect in a very positive and interesting way to a study showing that Sambucus nigra flower extract in combination with three other herbs has a very favorable effect on chronic constipation [31]. There is reference to a paper [32] and a handbook [33] where the use of Sambucus nigra is encouraged in treatment of gastrointestinal problems. In a review on Sambucus nigra, Lim [7] dedicated a section to its “Traditional Medicinal Uses”, and states “The fruit be depurative, weakly diaphoretic and gently laxative. A tea made from the dried berries is believed to be effective for colic and diarrhea”. Yöney, et al., [34] state that in the Eastern Mediterranean region medicinal plant use has been widely accepted for centuries as a treatment for both minor and major diseases; elderberry preparations being effective against stomach and intestinal ailments. Also, in the Western Mediterranean (e.g. Catalonia) Rigat, et al., [35] report that elderberry is still widely used in the treatment of stomach-ache, indigestion and constipation, and for the relief of complaints in the intestine (useful because of analgesic and anti-septic properties). Vallès, et al., [36,37] provide a comprehensive assessment of the popular medicinal uses of elderberry in Catalonia where amongst others anti-diarrheal, anti-flatulence, anti-acid, anti-septic and anti-inflammatory properties are cited. The exploitation of elderberry because of anti-inflammatory and anti-septic properties for treatment of gastrointestinal ailments in Tuscany is mentioned by Uncini Manganelli and Tomei [38]. Leporatti and Corradi [39] indicate that various Sambucus nigra preparations have been effectively used in central Italy as a laxative and in treatment of general digestive problems. There is, therefore, quite a widespread use of different preparations of elderberry in treatment of gastrointestinal problems in humans.

There is also well-recognized documentation of a positive effect of elderberry on several other situations. For example, Reider, et al., [40] have recently shown in a clinical study with humans that there was a positive effect on gut microbiota. The main result was an increase in the relative abundance of Akkemansia spp. Interestingly Namakin, et al., [41] were able to demonstrate an effect on the gut-brain-axis using rats with irritable bowel syndrome. Also using rats Bobek, et al., [42] have provided evidence that a diet based on a 4% elderberry extract is effective in protection from the development of colitis (inflamed colon/large intestine). Gray, et al., [43] have shown that Sambucus nigra has components that are insulin-like and have insulin-releasing activity in vitro. The positive effect of various elderberry preparations on gastrointestinal ailments is shown in Table 2.

Treatment of Bacterial and Viral Infections in the Upper Respiratory Tract: Colds and Influenza

Elderberry has a long history in the treatment of colds and influenza. Unlike its widespread use through hundreds of years on gastro-intestinal problems, clinical studies on humans have demonstrated that elderberry extracts can inhibit influenza a and b infections, and pre-clinical studies have shown antiviral effects. There are several human trials carried out [44,45]. Three were randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies investigating the efficacy of a proprietary elderberry syrup (Sambucol®), and one with a lozenge for treating symptoms associated with influenza. In the two first studies which involved 27 and 60 patients respectively, patients treated with Sambucol® recovered significantly faster than patients in the control group. A placebo-controlled, double-blind study [44] was conducted on 27 individuals with influenza (symptoms for ≤24 hours). Patients were randomized to receive either Sambucol® or placebo daily for 3 days. Children (5- 11 years) received 2 tablespoons per day and adults (12 years and older) received 4 tablespoons per day for 3 days. A significant relief from symptoms, including fever, was experienced by 93.3% of the elderberry group within 2 days. In contrast, 91.7% of the placebo group did not show similar improvement until day 6 (p<0.001). Complete resolution (“cure”) was achieved within 2 to 3 days by approximately 90% of the elderberry group and within 6 days by the placebo group (p<0.001). Immune system tests found a higher level of influenza antibodies in patients receiving elderberry than those receiving the placebo, suggesting enhanced immune activity.

Another clinical trial with 60 adults [46] also demonstrated the safety and efficacy of standardized elderberry syrup (Sambucol®) in the treatment of influenza and its symptoms. In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving patients (18-54 years) with either influenza type A or type B, 15 ml of Sambucol® or a placebo was administered 4 times a day. Medication was initiated within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms (a potential weakness of this trial, as the elderberry preparation may have been even more effective with earlier intervention) and continued for 5 days. Study outcomes were determined from Visual Analogue Scores (VAS) measuring flu symptoms (aches and pains, coughing frequency, quality of sleep, nasal congestion, and mucous discharge) and self-evaluation questionnaires. Baseline VAS values were not significantly different between the two groups. During treatment, VAS values were significantly higher (noting improvement) for the treatment group than for the control group (p<0.001). Most VAS values in the elderberry group were close to 10 (pronounced improvement) after 3-4 days of treatment, whereas it took 7-8 days before the placebo group reached similar levels. Global evaluation scores (symptoms and overall wellness scores combined) for the elderberry group showed a pronounced improvement after a mean of 3.1 days compared to 7.1 days for the placebo group (p<0.001). Moreover, a significantly larger number of patients in the control group resorted to “rescue medication,” such as an analgesic (i.e., paracetamol [acetaminophen]) or nasal spray, compared with the treatment group (p<0.001).

A further clinical trial was designed [46] to examine the effect of a proprietary slow-dissolving elderberry extract lozenge in the treatment of flu-like symptoms. The study was conducted at the Shanghai Construction Technical College (Shanghai, China) in March-April 2009. The patients were aged 16-60 years and presented with flu symptoms in less than 24 hours after an outbreak. The patients had at least 3 of the following symptoms: fever, headache, muscle aches, coughing, mucus discharge, and nasal congestion. Using computer-generated randomization, the patients were assigned either lozenges containing 175 mg elderberry extract (Herbal Science Singapore Pte. Ltd.; Singapore; n=32) or placebo lozenges (n=32) that were similar in appearance and taste. The patients took 4 lozenges/day for 2 days at mealtimes and bedtime. The following symptoms were monitored using a visual analogue scale (VAS): fever, headache, muscle aches, cough, mucus discharge from the respiratory tract, and nasal congestion. The patients were asked to score their improvements in relief of their symptoms 4 times a day for 2 days on a scale of 0 (no problems) to 10 (pronounced problems). At baseline, 15 patients in the elderberry group and 9 in the placebo group had fevers ranging from 37.3-38.8℃. After the first 24 hours, there was a statistically significant decrease in fever compared to baseline in the elderberry group (p<0.0001). After 48 hours, all of the patients with fevers at baseline in the elderberry group had normal temperatures. In contrast, most patients with fever in the placebo group did not show improvement after 48 hours and only 2 had normal temperatures. All patients reported headaches at baseline. After 24 hours, there was a significant reduction in headache compared to baseline in the elderberry group (p<0.0001). After 48 hours, 78% of the elderberry group patients did not have headaches and 22% had mild headaches (VAS=1). In the placebo group, headaches became more severe compared to baseline after 48 hours (p<0.0001), and no improvements in headache were reported. At baseline, all of the patients in the elderberry group and 87.5% of patients in the placebo group had nasal congestion [47].

After 24 hours, the elderberry group showed a significant improvement in nasal congestion (p<0.0001). After 48 hours, 50% of patients in the elderberry group had no nasal congestion. In the placebo group, nasal congestion was worse for most patients (p=0.049), and only 2 patients reported improvements after 48 hours. About half of the patients in each group reported coughing at baseline. No significant improvement in coughing was found after the first 24 hours in the elderberry group. However, after 48 hours, cough had improved in the elderberry group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.093). Nonetheless, the elderberry group showed significant improvements in coughing when compared to the placebo group at 48 hours (p<0.0001). In the placebo group, the majority of patients reported a worsening of their cough and the VAS score increased compared to baseline after 48 hours (p=0.0041). No adverse effects were reported [47]. The author concludes that the administration of this proprietary elderberry extract “can rapidly relieve influenza-like symptoms.” He comments that the results suggest that the proprietary elderberry extract is similar or superior to antiviral drugs in treating influenza-like symptoms and shortening the duration of illness, but more research is needed to determine if the extract can reduce viral shedding [48]. The absence of adverse events leads the author to suggest that the proprietary elderberry extract should be studied in children and the elderly. He also suggests research on the proprietary elderberry extract in treatment of pandemic H5N1 avian influenza infections based on unpublished data by Roschek, et al., [48] showing that flavonoids from elderberry bind to the viral strain in vitro. More research is needed to confirm these results, including clinical trials which use objective measurements of symptoms and laboratory-confirmed influenza cases.

A study published in 2009 has shown that flavonoids from elderberry bind to the surface of the H1N1 influenza virus and interfere with host cell receptor recognition and/or binding [48]. Direct Analysis in Real Time (DART) coupled to a Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer (TOF-MS) can be used to determine the chemical composition of botanical extracts with little to no sample preparation. In this study, the authors used bioassays, DART, and TOF-MS to identify the constituents of an elderberry extract that are active against H1N1 human influenza A. Clinical studies have thus shown that elderberry extracts inhibit human influenza A and B infections [48].

Conclusions

It is evident that there is a wealth of information on the use of a Sambucus nigra preparation against a series of gastrointestinal conditions, and the common cold and influenza in humans. It has been estimated that about 10% of the population world-wide suffers stomach/intestinal ailments daily. One of the main problems is the fact that elderberry can be used for a variety of disorders (Table 2), for example, constipation and diarrhea. This raises the question of how the same preparation can be active against two quite different disorders. This question can only be answered when research has been carried out on the purified components of elderberry.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Austin TF (2012) Ethnobot. Res Applic 10 203-234 201.

- Blumenthal M (2003) The ABC Clinical Guide to Elder Berry. In: The ABC Clinical guide to herbs The American Botanical Council, 6200 Manor Rd, Austin, TX 78723.

- Charlebois D (2007) Elderberry as a Medical Plant In: Issues in new crops and new uses J. Janick and A. Whipkey eds; pp: 284-292 ASHS press Alexandria, VA.

- Vlachojannis JE, Cameron M, Chrubasik S (2010) A systematic review on the Sambucus fructus effect and efficacy profiles. Phytother Res 24(1): 1-8.

- Blochwich M The Anatomy of the Elder; Original Edition (1677) Re-Edited 2010. Published by Berry Pharma AG.

- Atkinson MD, Atkinson E (2002) Sambucus nigra L. J Ecology 90: 895-923.

- Lim TK (2010) Sambucus nigra: In “Medicinal and non-medicinal edible plants”, Berlin: Springer Netherland pp. 30-44.

- Pryme IF, Dale TM (2016) Elderberry (Sambucus nigra), its constituents and use in treating gastrointestinal ailments. In: Medicinal Plants: Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Therapeutics 4: 197-222.

- Pryme IF, Aarra TM (2021) Exhaustive overview of dietary plant lectins: Prospective importance in the Mediterranean diet. Am J Biomed Sci Res 13(4): 339-358.

- Pryme IF (2012) Misteltoe lectins in cancer therapy: Administration by the oral route or by subcutaneous injection? A review. Nat Prod Res Rev 1: 79-98.

- Van Damme EJM, Peumans WJ, Pusztai A, Bardocz S (1998) Properties and biomedical applications. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, UK.

- Eifler R, Pfull,er K, Gockeritz W, Pfuller U (1993) Lectins : Biology, biochemistry, clinical biochemistry In: Basu J, Kundu P, Chakrabarti P eds. New Delhi: M/S Willey Eastern Ltd.

- Peumans WJ, Van Damme EJM (1996) Prevalence, biological activity and genetic manipulation of lectins in foods. Trends in Food Technology 7: 132-138.

- Sharma R, van Damme EJM, Peumans WJ, Sarsfield P, Schumacher U (1996) Lectin binding reveals divergent carbohydrate expression in human and mouse Peyer´s patches. Histochem Cell Biol 105(6): 459-465.

- Barak V, Halperin T, Kalickman L (2001) The effect of Sambucol, a black elderberry-based on the production of human cytokines. 1. Inflammatory cytokines. Eur Cytokine Netw 12(2): 290-296.

- Barsett H, Aslaksen TH, Gildhyal P, Michaelsen TE, Paulsen BS (2012) Comparison of carbohydrate structures and immunomodulating properties of extracts from berries and flowers of Sambucus nigra L. Eur J Medicinal Plants pp. 2 216-229.

- Aricigil S, Pryme IF (2014) Potential beneficial effects of plant lectins on health: A review. In: Natural Products: Research Reviews 2: 1-27.

- Hearst C, McCollum G, Nelson D, Ballard LM, Millar BC, et al. (2010) Antibacterial activity of elder (Sambucus nigra L) flower or berry against hospital pathogens. J Med Plants Res: 1805-1809.

- Novelli S. (2003) Developments in berry production and use. Bi-weekly Bul, Agriculture of Agroalimentaire Canada: 16: 5-6.

- (2005) Monograph on Sambucus nigra. Alt Med Rev 10(1): 51-4.

- Cejpek K, Maloušková I, Konečny M, Velíšek J (2009) Antioxidant activity invariously prepared elderberry foods and supplements. Czech J Food Sci 27: S45-S48.

- Uncini Manganelli RE, Zaccaro L, Tomei PE (2005) Antiviral activity in vitro of Urtica dioica L., Parietaria diffusa and Sambucus nigra L. J Ethnopharmacol 98(3): 323-327.

- Merica E, Lungu M, Balan I, Matei M (2006) Study on the chemical composition of Sambucus nigra L. Essential oil and extracts. Nutra Cos: Nutra Cos 5(1): 25-27.

- Henneberg M, Stasiulewicz M (1993) Herbal ethnopharmacology of Lithuania/Vilnius region. Medicaments et ailments: l´approcheethnopharma-cologique: pp. 243-255.

- Madaus G, Lehrbuch der Biologischen Heilmittel. Band III. Georg Thieme Verlag 1(938): 2422.

- Grieve MA (1931) Modern Herbal London, Jonathan Cape: pp. 265-277.

- Karmazín M, Hubík J, Dusek J (1984) Seznam léciv rostlinného puvudu. V7J Spofa, Praha: pp. 150-151.

- Wichtl M (2004) Herbal drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals 3rd.ed. Medpharm Scientific Publishers GmbH, Stuttgart: pp. 549-550.

- Chatterjee A, Yasmin T, Bagchi D, Stohs SJ (2004) Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori in vitro by various berry extracts, with enhanced susceptibility to clarithromycin. Mol Cell Biochem: 265(1-2): 19-26.

- Cordain L, Toohey L, Smith MJ, Hickey MS (2000) Modulation of immune function by dietary lectins in rheumatoid arthritis. British J of Nutr 83(3): 207-217.

- Picon PD, Picon RV, Costa A, Sander GB, Karine M Amaral, et al. (2010) Randomized clinical trial of phytotherapic compound containing Pimpilla anisum, Foeniculum vulgare, Sambucus nigra, and Cassia augustifola for chronic constipation. BMC Compl and Alter Medi 10: 17-25.

- Kilham C (2000) Health benefits boost elderberry; Herbal Gram 50: 55-57.

- Bisser NG (1994) Herbal drugs and phytopharmaceuticals: A handbook for practice on a scientific basis. Stuttgart: Medipharm Scientific.

- Yöney A, Prieto JM, Lardos A, Heinrich, M (2010) Ethnopharmacy of Turkish-speaking Cypriots in Greater London. Phytother Res 24(5): 731-740.

- Rigat M, Bonet MA, Garcia S, Garnatje T, Vallès J (2007) Studies on ethnobotany in the high river Ter valley (Pyrenees, Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). J Ethnopharmacol: 113(2): 267-277.

- Vallès J, Bonet MA, Agelet A (2004) Ethnobotany of Sambucus nigra L in Catalonia (Iberian Peninsula): The integral exploration of a natural resource in mountain regions. Economic Botany 58: 456-469.

- Vallès J, Bonet MA, Garnatje T, Muntane J (2010) Sambucus nigra L in Catalonia (Iberian Peninsula). In: Underutilized and Underexploited Horticultural crops pp. 393-424.

- Uncini Manganelli RE, Tomei PE (1999) Ethnopharmaco-botanical studies of the Tuscan Archipelago. J Ethnopharmacol: 65(3): 181-202.

- Leporatti ML, Corradi L (2001) Ethnopharmacobotanical remarks on the Province of Chieti town (Abruzzo, Central Italy). J Ethnopharmacol: 74(1): 17-40.

- Reider S, Watschinger C, Langle J Pachmann U, Przysiecki, Nicole Przysiecki, et al. (2022) Short- and long-term effects of a prebiotic intervention with polyphenols extracted from European Black Elderberry-sustained expansion of Akkermansia spp. J Pers Med 12(9): 1479.

- Namakin K, Moghaddam MH, Sadeghzadeh S, Mehranpour M, Vakili K, et al. (2023) Elderberry diet improves gut-brain axis dysfuntion, neuroinflammation, and cognitive impairment in the rat model of irritable bowel syndrome. Metab Brain Dis 38(5): 1555-1572.

- Bobek P, Nosalkova V, Cerna, S (2001) Influence of diet containing extract of black elder (Sambucus nigra) on colitis in rats. Biologia 56: 643-648.

- Gray AM, Ammbdel Wahab YH, Flatt PR (2000) The traditional plant treatment, Sambucus nigra (elder), exhibits insulin-like and insulin-releasing actions in vitro. J Nutr 130(1): 15-20.

- Zakay Rones Z, Varsano N, Zlotnik M, O Manor, L Regev, et al. (1995) Inhibition of several strains of influenza virus and reduction of symptoms by an elderberry extract (Sambucus nigra L) during an outbreak of influenza B Panorama) Alt and Complement Med 1(4): 361-369.

- Zakay Rones Z, Thom E, Wollan T (2004) Randomized study of the efficacy and safety of oral elderberry extract in the treatment of influenza A and B virus infections. J Int Med Res 32(2): 132-140.

- Kong FK (2009) Pilot clinical study on a proprietary elderberry extract: efficacy in addressing influenza symptoms. Online J of Pharmacol and Pharmacokin 5: 32-43.

- Murkovic M, Abuja PM, Bergmann AR, A Zirngast, U Adam, et al. (2004) Effects of elderberry juice on fasting and postprandial serum lipids and low-density lipoprotein oxidation in healthy volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Euro J Clin Nutr 58(2): 244-249.

- Roschek B, Fink RC, McMichael, Alberte RS, Dan Li (2009) Elderberry flavonoids bind to and prevent H1N1 infection in vitro. Phytochem: 70(10): 1255-1261.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.