Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Intellectual Disability and Social Inclusion: Clinical and Medico-Legal Aspects

*Corresponding author: Letteria Tomasello, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, Italy.

Received: May 15, 2024; Published: June 05, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.22.003006

Abstract

This work aims to deepen the field of intellectual disability, reviewing recent scientific literature and the redefinition of diagnostic criteria and diagnostic guidelines: the DM5 (American Psychiatric Association) [1], which reiterates the need, in addition to cognitive evaluation, for an in-depth analysis of adaptive behaviour, to identify strategies for intervention and social inclusion. Management of adults with intellectual disabilities, both institutionalised and non-institutional, is in most cases devoid of periodic assessments of the levels of competence achieved after the first diagnosis, usually carried out in childhood and/or youth, whose treatment is not changed over time. In particular, the aim is to analyze the evolution of cognitive abilities and adaptive levels over the life span, as well as their interactions and influence other possible variables both individual and context.

Keywords: Disability and Inclusion, Clinical Aspect, Medico Legal Aspects

Introduction

In the course of time, a socially shared representation of disability has been constructed; like any other human phenomenon, this social representation is influenced by the dominant thought in different historical eras. Therefore, it may be useful to first outline a brief excursus on the historical-cultural evolution of the social image and, consequently, of the methods of approach and management to the person with disabilities.

Disability, in the past has been strongly opposed by virtue of the ideals of strength and beauty, any form of physical imperfection or illness, was attributable to a divine punishment for some guilt committed [2]. Aristotle 1990 [2], argued that the task of the state was to prevent the rearing of babies born deformed, so as to avoid the expenditure of money and energy. Plato argued that the task of medicine was exclusively aimed at treating only the healthy in body and spirit [3]. In the fifth century BC, Roman law imposed the suppression of children born deformed, throwing them from the Tarpea Cliff, a fate of marginalization and abandonment was reserved also for soldiers who suffered great mutilation while receiving great honors. In Jewish culture, in the Old Testament, it was impossible for anyone with physical deformities to take part in religious rituals. With Christianity, the values of charity, piety and defense of the weak and the sick are affirmed, because all children of God and there has been a first change in the perception and social attitude towards the different and the weakest, but the process is stopped, with the papacy of Gregory the Great (590-604), according to whom a healthy soul could not reside in a sick body. In the medieval period there remains the belief in physical and mental disasbility, supported by the Catholic Church, which reaffirms the link between disease and sin, mental illness being considered the consequence of wickedness and sinful conduct, led to the resolution of relegating the mentally ill to special facilities, which later became asylums.

In the thirteenth century, asylums are born and grow throughout Europe. With the Enlightenment disability can be cured [2]. The disabled are divided into curable and incurable, the mentally ill, are destined to be removed from society and interned for the rest of their existence, other forms of disability, provided for treatment in hospitals. A fundamental step in the evolution of the social representation of disability is due to the publication of Darwin’s work "The origin of the species" (1859) [4] which, introducing the concepts of "evolutionism" and "natural selection", produces the fundamental epistemological revolution in Western scientific culture.

The English philologist Herbert Spencer (1851) [5] was the first to apply Darwinian theories to society, affirming the existence in nature of a real state of war, which induces the suppression of the weakest to the advantage of the strongest and smartest, so as to foster the progress of the human species. We cannot forget, however, that Darwinian evolutionism was also inspired by intrinsically racist conceptions, such as the nascent discipline of "racist anthropology" from which arose the so-called eugenics, aimed at the production of a superior race, objective of Nazism [2]. In fact, in the thirties of the twentieth century, with the coming to power of Hitler, disabled people - especially those with mental deficits - also became the object of persecution and mass destruction [6]. Only from the second half of the twentieth century, a movement of deep criticism and condemnation of total institutions, as places of exclusion/segregation, began to spread. The sociologist Goffman, in the collection of Essays "Asylums" (1961), emphasizes the primary containment and custody of psychiatric structures, with the aim of protecting society from people suffering from psychic pathologies, considered a social danger. In Western culture, the de-institutionalizing approach that in Italy led in 1978 to the approval of Law 180, the so-called "Basaglia Law", which decreed the closure of asylums, has been increasingly established until it became dominant. From the end of the seventies, with the overcoming of the mere perspective of custody/ segregation, laws and regulations that institutionalize the spread of socio-social structuresalternative health care more oriented towardas a therapeutic and rehabilitative approach, as will be summarized in the next paragraph, especially in reference to the establishment of socio-measures to promote and support wider social inclusion.

Promoting the Rights and Integration of People with Intellectual Disabilities

With Law No. 104/1992 [7] the educational centres were transformed into day care centres, "the integration and social integration of the disabled person is achieved through [...] the establishment or adaptation of socio-rehabilitation and educational day centres with educational value". This "framework law for assistance, social integration and the rights of disabled people" the law has set itself the goal of preventing and removing the conditions that prevent the full development of the person with disabilities, based on the assumption that, by providing adequate support and support to disabled people and families, autonomy and social integration can be promoted. The institutions of "residential socio-rehabilitation and educational centres" and "housing communities" have been envisaged as measures. The Law n. 328/2000 [8] has ordered that in every territorial area "socio-rehabilitation centres" and "residential and semi-residential structures for subjects with social fragility" are established (art. 22). Residential services are small institutions or communities that welcome disabled people who do not have the support of their families. The Daytime Day Centre, on the other hand, is aimed at people with cognitive disabilities, who have a certain degree of self-sufficiency, but who cannot be placed in a protected working environment.

In December 2006, the United Nations Assembly approved the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, ratified by the Italian Parliament with L. 18/2009 which aims to protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all civil liberties by people with disabilities [9].

The newly created residential and/or semi-residential structures are real reception and support services for users and families in order to meet their basic needs but also and not secondarily enhance residual resources and skills. Where possible, the legislation provides for the application of two types of home interventions: the home care service (SAD) and the Integrated Home Care Service (ADI)

The Home Care Service (SAD) provided by the Municipality is aimed at disabled people who are not self-sufficient with different levels of dependence; the aim is to integrate the skills of the disabled adult, providing support for small tasks and different types of activities. The person, remaining in his own environment of life, is not excluded from social life and can maintain relations with the outside and services present in the territory. The Integrated Home Care Service (ADI) in addition to home care offers necessary medical and rehabilitation. With the Decree of the President of the Republic of 4 October 2013, Italy adopted the first "Biennial Action Programme for the promotion of rights and the integration of people with disabilities" [10], thanks to which there is an important change, both from a political and design point of view on the subject. In addition to the care needs of people with disabilities, the rights of people with disabilities are respected, with the involvement of the political administration (local, regional, national). Italy commits itself to the international community on the occasion of the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Law of 3 March 2009, n.18) which marked the transition from a vision of disability as a condition of illness and inferiority to a conception aimed at respect for human rights and the enhancement of individual differences. The general principles of the Convention are as follows:

a. Respect for intrinsic dignity, individual autonomy, including the freedom to make their own choices, and the independence of individuals.

b. The principle of non-discrimination.

c. Full and effective participation and inclusion in society.

d. Respect for difference and acceptance of people with disabilities as part of human diversity and humanity itself.

e. Equal opportunities.

f. Accessibility.

g. Equality between men and women.

h. Respect for the development of the capacity of children with disabilities and respect for the right of children with disabilities to preserve their identity.

On the basis of the first programme, the Decree of the President of the Republic of 12 October 2017 promulgated a second "Biennial Action Programme for the Promotion of the Rights and Integration of Persons with Disabilities" [10], (prepared by the National Observatory on the Condition of Persons with Disabilities (OND) and based on the same principles as the first programme. The implementation of this Programme, in addition to the commitment of the national government and the Parliament, calls for the coordinated intervention of local governments and regional administrations.

At European level, on 3 March 2021, the European Commission published the new Strategy 2021-2030 on the rights of people with disabilities, which follows the previous European Disability Strategy 2010-2020. The latter paved the way for a barrier-free Europe aimed at the emancipation of individuals with disabilities. The new Strategy proposes various activities aimed at ensuring better living conditions for the 100 million people with disabilities living in the European Union, encouraging their full participation in the community while respecting the rights of equality and non-discrimination. These activities will be implemented through the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and European legislation on fundamental rights. In particular, the initiatives outlined by the European Strategies are based on three fundamental themes:

a. EU Rights: Proposal for a European Disability Charter from 2023, to facilitate the free movement of people with disabilities in all EU countries.

b. Independence and Autonomy: preparation of guidance aimed at increasing the quality of social services for people with disabilities and to support their right to an independent and autonomous life.

c. Non-discrimination and Equal Opportunities: a central objective of the Strategy is to protect people with disabilities from all forms of discrimination and violence, ensuring equal opportunities and access to health, justice and education, sport, tourism and employment.

The European Commission urges Member States to contribute to this new enhanced strategy, which serves as a framework for EU actions and for the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

With regard to the specific Italian context, the main legislation, having as its central object the theme of disability, is Law 5 February 1992, n.104, also called: "Framework Law for Assistance, Social Integration and the Rights of Disabled Persons" [7] (OJ General Series No. 39 of 17.02.1992 - Ordinary Supplement No. 30), the general objectives of which are as follows:

a. To guarantees full respect for the human dignity, freedom and autonomy of the disabled person, promoting their full integration into the family, school, work and society.

b. Prevents and eliminates the disabling conditions that hinder the development of the human person, the participation of the disabled person in the life of the community, as well as the realization of civil, political and patrimonial rights.

c. Pursue the functional and social recovery of the person suffering from physical, mental and sensory disabilities and provide services and services for the prevention, treatment and rehabilitation of disabilities, as well as the legal and economic protection of the disabled person.

The European Commission has set up measures to overcome the marginalisation and social exclusion of the disabled. A regulation specifically aimed at promoting the right to work of people with disabilities is Law No. 68 of 12 March 1999, called "Norms for the right to work of disabled people" [11] (OJ No 68 of 23-03-1999 - Suppl. Ordinary No.57). The purpose of this provision is to ensure the integration and occupational integration of persons with disabilities through targeted support and placement services (Art.1). It shall apply to:

a. Persons of working age with physical, mental or sensory handicaps and persons with intellectual disabilities, who reduce their working capacity by more than 45%, established by the competent committees for the recognition of civil invalidity in accordance with the indicative table of the rates of disability for disabilities and disabling diseases approved, pursuant to Article 2 of the Legislative Decree 23 November 1988, n. 509, by the Ministry of Health on the basis of the International Classification of Impairments drawn up by the World Health Organization; and to persons under the conditions referred to in Article 1, paragraph 1, of Law No. 222 of 12 June 1984.

b. Persons with a degree of invalidity of more than 33 per cent, established by the National Institute for Insurance against Accidents at Work and Occupational Diseases (INAIL) in accordance with the provisions in force.

c. Blind or deaf persons, referred to in Laws No. 382 of 27 May 1970, as amended, and No. 381 of 26 May 1970, as amended.

d. War invalids, civil war invalids and invalids for service with disabilities assigned from the first to the eighth category referred to in the tables annexed to the single text of the rules on war pensions, approved by d.p.r. 23 December 1978, n. 915, and subsequent amendments.

Moreover, in Art.3, this law establishes Mandatory Recruitment and Reserve Quotas, in particular:

1) Public and private employers shall be required to employ workers belonging to the categories referred to in Article 1 to the following extent:

a) Seven per cent of employed workers, if they employ more than 50 employees.

b) Two workers, if they employ between 36 and 50 employees.

c) A worker, if they employ 15 to 35 employees.

i. For private employers employing 15 to 35 employees the obligation referred to in paragraph 1 applies only in the case of new hires (repealed by Legislative Decree No. 151 of 2015).

ii. For political parties, trade union organisations and non-profit organisations operating in the field of social solidarity, care and rehabilitation, the reserve share is calculated exclusively with reference to technical personnel-executive and performing administrative functions (paragraph as amended by Legislative Decree no. 151 of 2015).

iii. For the police, civil protection and national defence services, the placement of disabled people is provided only in the administrative services.

iv. The obligations of recruitment referred to in this article are suspended in respect of companies that are in one of the situations provided for by Articles 1 and 3 of Law no. 223 of 23 July 1991 and subsequent amendments, or by Article 1 of Decree-Law 30 October 1984, n. 726, converted, with modifications, from law 19 December 1984, n. 863; the obligations are suspended for the duration of the programs contained in the relative demand for participation, in proportion to the activity effectively suspended and for the single provincial within. The obligations are also suspended for the duration of the mobility procedure governed by Articles 4 and 24 of Law No. 223 of 23 July 1991, as amended, and, if the procedure ends with at least five dismissals, for the period in which it remains the right of precedence to the assumption previewed from article 8, codicil 1, of the same law.

v. The rules for private employers apply to public economic bodies.

vi. The share of the reserve shall include workers who are recruited pursuant to Law No. 686 of 21 July 1961, as amended, as well as Law No. 113 of 29 March 1985, and Law no. 29 of 11 January 1994.

Despite the important changes that occurred with the promulgation of this legislation, if we consider the national data related to the employment of people with disabilities in Italy, a bleak picture emerges. From the analysis of the ISTAT statistics of 2015, it emerges that among people with serious functional limitations the employed are only 19.7%, against 46.9% among those with mild limitations, disability or chronic pathologies. The inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities, in particular, requires structured and complex interventions, in order to better ensure employment. Support for integration implies not only the removal of architectural barriers, but above all the creation and adoption in the workplace of innovative communication methods, language simplification, accessibility to resources and work tools.

Also, with a view to promoting full educational, work, social and family integration of people with disabilities, Law No. 328 of 8 November 2000 [12], "Framework Law for the implementation of the integrated system of interventions and social services" was promulgated. In particular, Article 14 (Individual projects for disabled people) is of fundamental importance. It provides, in fact, the right of every person with disabilities, and of those who represent him, to ask the Municipality to draft a personalized life project, in agreement with the ASL and the different institutional and social individuals who, In various ways, they help to achieve this social integration.

The progressive increase in attention and support for inclusion in education and employment has been accompanied by an increase in scientific knowledge on the different types and profiles of people with disabilities, producing, in particular, the availability of different diagnostic tools, useful for the recognition and management of different categories of individuals with their specific characteristics. Reference theories and validated protocols are currently available which, on the basis of shared criteria, make it possible to make a diagnosis of intellectual disability. Below we will review the main classifications proposed by the international literature.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM 5)

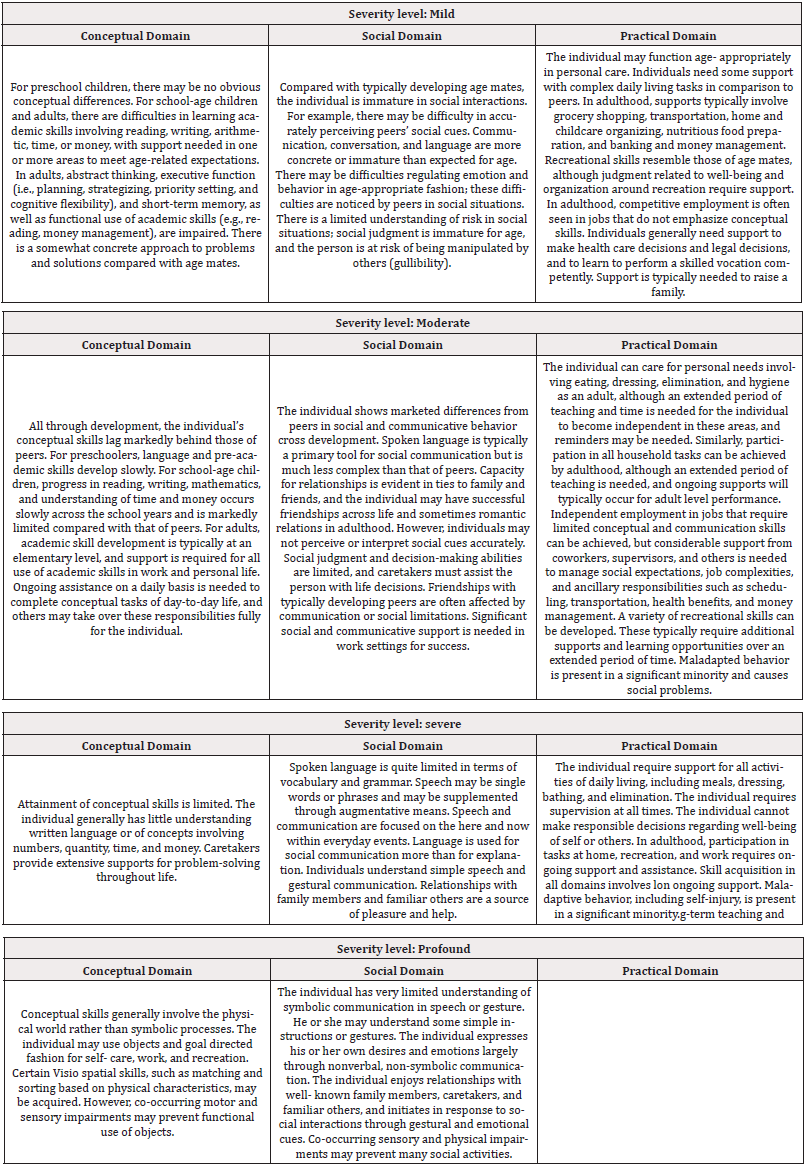

With the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) it is recognized the insufficiency of a Diagnosis based on merely psychometric parameters and to whose definition must contribute a complementary assessment of social adaptation. Mental retardation has been renamed Intellectual Development Disorder (IDD) in DSM-5 to reflect changes in U.S. federal law (Public Law 111-256), which replaced the term mental retardation with intellectual disability. The criteria for IDD has changed, and people with IDD are no longer categorized solely on the basis of IQ, although IQ must be at least two standard deviations from the mean (70 or less). IDD is characterized by deficits in cognitive abilities (e.g., problem solving, planning, reasoning, judgment) and adaptive functioning. Diagnostic criteria emphasize the importance of assessing both cognitive abilities and adaptive functioning. The severity level (mild, moderate, severe, or profound) of the intellectual disability is determined by the person's ability to meet developmental and sociocultural standards for independence and social responsibility, not by the IQ score.

To help determine a diagnosis, a table listing IDD severity levels (mild, moderate, severe, or profound) across three different domains (conceptual, social, and practical). With the introduction of DSM-5, the term mental retardation has been replaced by intellectual disability, equivalent to intellectual developmental disorder adopted in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 11th revision - ICD-11 (WHO, 2022); this confirms a progressive convergence between the two international classification systems. DSM-5 defines intellectual disability by including it in neurodevelopmental disorders:

"a disorder with onset in the period of development that includes deficits in both intellectual and adaptive functioning in conceptual, social and practical areas. The following three criteria must be met:

a. Deficits in intellectual functions, such as reasoning, problem solving, planning, abstract thinking, judgment, school learning and experience learning, confirmed by both clinical evaluation and individualized intelligence testing, standardized.

b. Lack of adaptive functioning that leads to the failure to meet the standards of development and sociocultural autonomy and social responsibility. Without constant support, adaptive deficits limit the functioning of one or more activities in daily life, such as communication, social participation and autonomous life, through multiple environments such as home, school, work environment and community.

c. Onset of intellectual and adaptive deficits during the development period".

In addition to the above diagnostic criteria, there are specifiers to outline the current level of severity (mild, moderate, severe, extreme) of intellectual disability (Table 1). The severity level is based on adaptive operation and not on IQ scores, as the adaptive operation defines the type and degree of assistance required, so that the person can maintain an adequate quality of life and ensure the highest possible level of psycho-social well-being.

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD)

The term Intellectual Disability (ID) has replaced the expression Mental Retardation, while the question whether the Intellectual Disability is a disability, or a health condition remains debated. This is central because, if Intellectual Developmental Disorders (IDD) were defined only as disability and not as a health condition, they would have to be deleted from the ICD [13] and classified using only International Classification Of Functioning, disability, and health (ICF) codesbut it is the ICD - not the ICF - that is used in 194 WHO member countries to define the responsibilities of governments in providing health care and other services to their citizens [14]. The eleventh review of the ICD involved 30 experts from 13 countries representing different regions of the WHO, who chose to code intellectual disability as a disorder and makes it clear, as it does not only concern intelligence, but the sphere of adaptation and is often present in comorbidities with other pathologies. A revision of this last revision is the inclusion of Individual developmental disorders, among neurological developmental disorders. They represent "a group of developmental conditions characterized by significant deficits of cognitive functions, associated with limitations of learning, adaptive behavior and abilities", with the following manifestations:

i. The IDD is characterized by a marked deficit of the central cognitive functions necessary for the development of knowledge, reasoning and symbolic representation with respect to children of the same age, culture and social environment. However, different patterns of cognitive impairment are found in particular IDD conditions.

ii. In general, people with IDD have difficulties with verbal comprehension, perceptual reasoning, working memory and processing speed.

iii. Cognitive impairment in people with IDD is associated with difficulties in the domains of learning, including school and practical knowledge.

iv. People with IDD typically manifest difficulties in adaptive behavior; that is, dealing with daily life activities in the same way as children of equal age, culture and environment. These difficulties include limitations in conceptual, social and practical skills.

v. People with IDD often have difficulties in managing behavior, emotions, and interpersonal relationships, and maintaining motivation in the learning process.

vi. IDD is a condition that affects the entire life cycle and requires the analysis of stages of development and life transitions.

According to scholars, to identify the different severity levels a clinical description is needed for each subcategory and the IQ score should be an element like others to determine the severity level. For the diagnosis of IDD there are difficulties in the diagnosis and detection of severity levels, in children under 4 years of age, due to the lack of reliable cognitive assessment tools [15]. Within the ICD-11 it is possible to place a provisional diagnosis of "unspecified IDD", for children under 4 years of age, and a subcategory of "other IDD" to be used for individuals over 4 years of age, when it is possible to make a diagnosis of intellectual disability, but the level of severity cannot be determined, due to comorbidity, for example, with psychiatric disorders, physical disability.

International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF)

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) was published by the World Health Organization [13] in 2001 and has been the subject of an annual update process by all users since 2011. This classification system is a new version of the (International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps - ICIDH) of 1980. The ICF is a reference classification of the WHO, along with the ICD-11 and the International Classification of Health Interventions - ICHI).

The WHO recommends the use of the ICD-11, to codify health conditions [13] and the ICF, to evaluate the functioning of the person. The ICF goes beyond the traditional medical perspective, and it pays attention to social and environmental factors, through a simple and shared language, it wants to offer a systematic classification and coding system for all countries. Disability is placed within the context of the person’s functioning, which interacts with the environment. More specifically, the ICF considers all aspects of health and some dimensions of well-being important for health itself, describing them as domains of health and domains related to it. The ICF is divided into two parts.

The first part, concerns Functioning and Disability, articulated in the component of the Body, which includes two classifications, one for the functions of the body systems and one for the body structures, and in the component of Activity and Participation that describes all aspects of operation from an individual and social perspective. Part 2, on the other hand, concerns the Components of Contextual Factors, namely Environmental Factors and Personal Factors, which interact dynamically with health conditions (diseases, disorders, injuries, etc.), helping to determine the operating states and possible disabilities of a person. The perspectives of the body, the person and society in constant interaction with each other therefore represent the basic dimensions of functioning (Figure 1).

Referring to intellectual disability, it is possible to propose an example of such complex inter-relationship.

This condition can lead to problems in terms of bodily functions and structures (delayed motor development, hypotonia, seizures, etc.), activities (school difficulties, work, etc.) and participation (social exclusion, discrimination, etc.), which mutually influence each other in a positive way (for example, participation, obtained by insertion in a diverse working environment, promotes social and communicative skills) or negative (for example, motor limitations may reduce the chances of social participation). Finally, it must be considered that these problems are affected by the effects of the context of belonging and vice versa [16].

Etiology

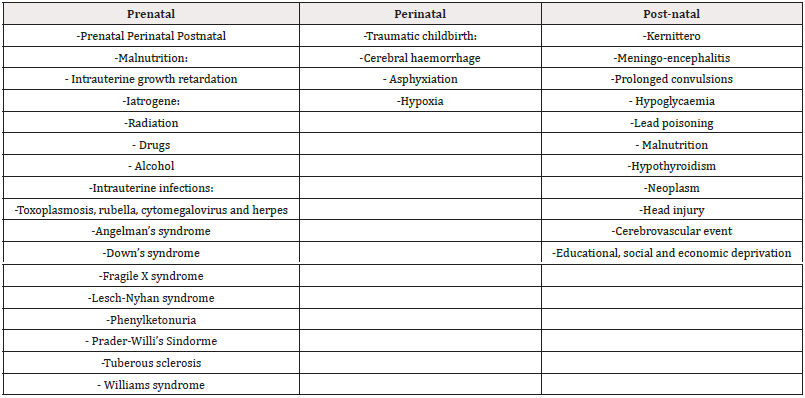

Intellectual disability is not a syndrome, but the common end result of different pathological processes, acting on the functioning of the central nervous system (DSM- IV-TR, 2000, p. 55) and affecting the psycho-social functioning of the individuals affected (DSM-5). It can be caused either by biological factors (genetic or not) or by environmental factors (Table 2).

Biological Causes

The biological causes of intellectual disability can be genetic and not genetic. The former consist of structural chromosome abnormalities or single gene abnormalities. The most known genetic syndrome, cause of intellectual disability, is Down syndrome. Non-genetic causal factors, on the other hand, act on the biological plane and can occur at different times of an individual’s life: before birth (prenatal causes), during (perinatal causes) and after childbirth (postpartum causes).

Biological and Genetic Causes

Recent advances in scientific research on the human genome have made it possible to identify the genetic and chromosomal alterations (both in number and shape) of many syndromes, which cause intellectual disability. More than 750 have been described, but the most frequent and known are about 27 that affect one person in every 400. More lacking is the research concerning the limit intellectual functioning, for which there is currently no exhaustive knowledge about causal factors (environmental and biological) [16].

Genetic syndromes, a cause of intellectual disability, differ in various aspects:

i. Gravity level (for example, Angelman syndrome is particularly severe, while the syndromes of Rett, 5p-, Down, fragile X, Williams and Prader-Willi are gradually less serious).

ii. Different stability of IQ over time.

iii. Different cognitive profiles. For example, people with Williams syndrome, with equal mental age, have greater language skills than those with Down syndrome, but their visuo-spatial performance is lacking; individuals with Prader syndrome-Willi show better performance in simultaneous memory tests rather than sequential memory tests.

iv. Variability may be greater or less within the same syndrome.

v. The effects of genetic alterations on emotional, social and behavioural development vary widely across syndromes. As an example, people with Smith-Magenis syndrome often exhibit self-aggressive and hetero-aggressive behavior and hyperactivity; individuals with Prader Willi syndrome tend to have difficulty in emotional control; Individuals with Williams syndrome show friendliness from the first approaches, while in fragile X syndrome a more shy and avoidant attitude prevails. By evaluating the different cognitive and behavioral profiles of the different genetic syndromes, it is possible to set up educational and enablement paths adapted to the needs of each.

The heterogeneity of the clinical picture, the etiology and the rarity of some syndromes, cause various diagnostic difficulties and at the level of intervention-therapy. A longer time interval between the onset of symptoms and a diagnosis is a cause of delayed treatment, which if started at an early stage, can allow for better results.

Non-Genetic Biological Causes

Non-genetic causes include prenatal, perinatal, postnatal, or more generally environmental factors.

Prenatal factors, which are likely to impair fetal brain development and determine intellectual disability, include:

i. Virus-induced infections (rubella, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, herpes simplex, HIV).

ii. Incompatibility (RH or AB0) of maternal and fetal blood.

iii. Intake of alcohol, drugs, tobacco by the mother (for example, foetus-alcohol syndrome).

iv. Exposure to drugs and toxic substances during pregnancy; severe malnutrition in pregnancy.

Perinatal causes include, for example, complications due to prematurity, asphyxia, and perinatal hypoxia, for possible dystopian childbirth. Finally, among the post-natal risks we find: encephalitis, meningitis, trauma and brain tumors, cerebrovascular events, toxic-metabolic intoxications [16].

Environmental Causes

Intellectual disabilities can also be caused by environmental factors, such as malnutrition and serious educational deficiencies (Baroff, 1986). However, cases of mental retardation due to socio-cultural disadvantage constitute a minority and have progressively decreased over time. Such factors are most often linked to diagnosis of "limit intellectual functioning" (IQ between 71 and 84) or "disorders in personality development" [16]. Research conducted in the United States has revealed results due to serious educational deficiencies, so as to stimulate the planning of interventions in a preventive perspective.

Intellectual Functioning

"Intellectual functioning" refers, in general, to the set of cognitive and behavioral skills necessary to solve cognitive problems related to both the satisfaction of the basic needs for personal survival and active social participation. Therefore, intellectual functioning is a wider expression of intelligence or cognitive abilities, and narrower set of "human functioning". In the twelfth edition of the AAIDD manual, QI scores are used as proxy measure for intellectual operation [17].

The Intelligent Construct and Its Measurements

As Cornoldi (2007) [18] states, "intelligence" refers to the ability to understand reality, compared to situations in which it is simply suffered or cannot be deciphered. Wechsler (1944, p. 3) defines intelligence as: "The aggregate or the global ability of the individual to act with a purpose, to think rationally and to confront effectively with his environment...". The term intelligence refers to the ability to identify various links between different objects and/or events of the experience in order to understand and solve problematic situations.

The definitions of intelligence are sometimes conflicting; as Cornoldi [18] points out, the conceptions of intelligence can be distinguished into two macrocategories: general and differential conceptions, the former refer to intelligence as a characteristic of the human species; the latter emphasize the different intellectual attitudes among individuals and in the same individual. In common language, intelligence is the element that differentiates people in the ability to cope with cognitive tasks and learning ability.

The shared position is that individuals are born with a qualitatively and quantitatively differentiated intellectual potential, but that can benefit from experiential contexts, as indispensable opportunities for the maturation and enhancement of the innate resources of the ability to use them. Several processes are involved in the actualization of individual skills, such as the speed of information processing, which increases during development to adulthood and decreases in the elderly [19]. Verguts, De Boeck, and Maris [20] argue, that the ability to solve cognitive problems such as those proposed by Raven’s matrices, would be affected by the speed in the elaboration of solution rules.

Adaptive Behaviour

"Adaptive Behavior" (AB) refers to the set of activities that an individual must perform every day, in order to be sufficiently autonomous and to adequately perform the tasks resulting from his social role, so as to meet the expectations of the environment for a subject of equal age and cultural context [21-25].

The AB construct has 4 key features:

The AC construct has 4 key features:

1) Tends to develop more and more complex over the years. Most evaluation scales, in fact, have items that refer to the entire life span, from childhood to adulthood. It’s planned to develop some skills in relation to age. During childhood, motor skills are fundamental, communication and socialization skills develop in childhood and then become increasingly complex. In adolescence and maturity, conceptual and abstract reasoning skills and abilities develop.

2) It is linked to the expectations of other people and the culture of belonging; in fact each culture establishes a minimum acceptable level in relation to age and the social role that the subject plays.

3) It is changeable, can improve or worsen as a result of interventions, accidents or other events.

4) It is evaluated on the basis of what the person actually does and does not know how to do. CA is a measure of the person’s typical performance, not the maximum performance. What is evaluated is the use of these skills in daily life.

Over the years the concept of adaptive behavior has evolved and undergone some changes. In 1992, the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR), now called AAIDD, proposed a 10-factor model for defining adaptive behavior, which are: communication, self-care, home life, social skills, use of community resources, self-determination, health and safety, school operation, leisure and work. Such abilities were considered for the diagnosis of intellectual disability.

It was in 2002 that the three factors initially proposed by Heber (1961) were taken into consideration and adapted behavior was defined as a set of conceptual, social and practical skills that were learned by people to function in their daily lives. This definition is almost identical to the most recent definition in the latest edition of the Terminology & Classification Manual proposed by the AAIDD, published in 2010, according to which "Adaptive behavior is the set of conceptual, social and practical skills that are learned and put into practice by people in their daily lives". Practical skills means: self-care, the management of the money, professional skills, safety, health care, daily life activities (cooking, washing, going to the toilet); social skills refer to interpersonal skills, social responsibility and self-esteem, respect for rules, Finally, conceptual skills refer to language, reading and writing, the concept of money, time and numbers [26,27].

Adaptive behavior, which consists of different skills: motor, practical, social, conceptual and abstract [28], constitutes an evolutionary construct that develops in childhood, stabilizes and then has a decline in old age. In the various age groups different skills will develop, starting from the motor, practical, social skills to gradually get to the more abstract ones. Adaptive behavior is evaluated on the basis of the performance of the subject at home, at school, at work, in the relationship with others in relation to the community context of his age [27]. This construct is specific to the context, learning and manifestation of certain adaptive skills depends on the expectations of the group and the environments attended. A subject could manifest a different adaptive behavior depending on the environment, moreover, could improve some skills following surgery programs and could worsen following physical or emotional trauma, or accidents [28]. The measurement of adaptive behavior is a fundamental element, together with intelligence, for the diagnosis of intellectual disability I. The level of impairment of adaptive behavior determines the level of severity of intellectual disability [26]. In diseases such as ADHD, autism, behavioural disorders, disorders and learning difficulties, there is often impairment of adaptive behaviour [27].

Tools for Assessing Adaptive Behaviour

The main tools for evaluating adaptive behaviour will now be analysed. This evaluation has two objectives: to identify the presence or absence of a deficit in the SO and to identify the strengths and weaknesses in order to create targeted intervention programmes.

In 1961, when Heber first introduced adaptive behavior, the only tool available was the Vineland Social Maturity Scale (VSMS), published by Edgard Doll in 1936 [29]. Doll, in fact, had observed that the assessment of subjects with intellectual disabilities was not sufficient and complete without an assessment of his adaptive behavior [28]. The author focused on the assessment of social competence, as he believed it was the most deficient feature in subjects with DI. By social competence he meant "the functional capacity of human organisms to exercise personal independence and social responsibility", in the 60’s/70’s Doll’s thought found confirmation, with the introduction of this construct that becomes a diagnostic criterion for a diagnosis of intellectual disability. Around those years, numerous research was therefore carried out to develop a test that measured adaptive behavior [26]. The scales of evaluation of Adaptive Behavior, are based on an indirect measurement, interviewing a person who adequately knows the individual to be evaluated, except for the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System- II, which can be filled in directly by the respondent, in case the purpose is not diagnostic [28].

Numerous factor analyses have been carried out to verify the psychometric validity of these instruments. From these analyses, 4 factors emerged [26]:

1) Motor or physical competence, including fine and coarse motor skills, walking and basic nutrition.

2) Conceptual skills, involving reading and writing skills, receptive and expressive language and money management.

3) Social skills, covering all aspects of social life, friendships, understanding and reasoning.

4) Practical skills that include housework, food preparation, washing, dressing and washing.

At the moment there are several adaptive behavior scales standardized and psychometrically valid, the main ones are: Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, second edition, ABAS-II [29], Adaptive Behavior Diagnostic Scale, ABDS [30]; the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, second edition [31] and the Scales of Independent Behaviour, Revised (SIB-R; Bruininks, et al., 1996) which, however, despite being a well-built and robust tool for measuring AC from a psychometric point of view, is a bit dated since its last version dates back to 1996 [26,27,32]. It is in fact very important for the instruments measuring the AC, a periodic update. The most current scales should evaluate the use of electronic instruments, such as a mobile phone or a microwave, a computer, replacing older elements, such as a telephone directory [27].

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition (VABS-II)

The VABS-II allows the assessment of adaptive behavior, that is, the activities that the subject carries out daily to respond to the autonomy and social responsibility of people of the same age and cultural context, of subjects aged from 0 to 90 years. It is a semi-structured interview that is administered to a caregiver or person who has a good knowledge of the subject whose adaptive behavior is to be evaluated. The interview is administered by a properly trained psychologist or other professional.

It is present in 3 versions:

i. The Survey Forms, the Survey Interview Form and the Parent/Caregiver Form, which are identical and differ only in the mode of administration used, then interview or grading scale. They include 4 scales: Communication, Daily Living Skills, Socialization and Motor Skills.

ii. The Expanded Interview Form, which consists of all the items in the Survey Forms plus others for the investigation of other adaptive abilities.

iii. Teacher Rating Form, which measures adaptive skills in the school context.

iv. Vineland-II Survey Forms, which represent a revision of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales [24], itself a revision of the Vineland Social Maturity Scale (Vineland SMS).

Performance adaptive behavior deficits are considered to be about two below-average standard deviations (hence they score less than or equal to 70) in at least one of the three domains of adaptive behavior or total score [28,33]. Tassé and colleagues (2020), note in the case of mild intellectual disability in adults, are compromised abstract thinking, executive functions (e.g. strategy development, planning) and short-term memory, as well as the functional use of school skills. In the social field, the individual presents difficulties in social interactions, as communication and language are more immature than expected according to age. As for the practical field, the individual can succeed in personal care, needing help to shop, manage the house, finances, prepare meals.

In the case of moderate intellectual disability in adults, the development of mathematical skills is stationary in elementary school and the person requires continuous support to carry out conceptual activities in daily life. In the social sphere, the individual has poor spoken language and relationship skills are limited to close ties with family or friends. Social judgment and decision-making skills are compromised. In practice, the individual, after a long period of learning, can take part in all domestic activities and, with appropriate support, can also achieve some work independence.

In the case of severe intellectual disability, the attainment of conceptual skills is limited in the conceptual field. In the social sphere language is limited and the individual may have to resort to augmentative tools. In the practical field requires support in every daily activity, to wash, dress, make decisions, participate in household tasks. Typically, the interview takes 20 to 60 minutes. This is a semi-structured interview that has advantages, such as the fact that the procedure is closer to a chat than to a formal interview or even less to a questionnaire: the examiner should not read the questions, nor have them read, but must ask general questions about the activities that the individual, to which the interview refers, carries out and ask any questions in depth to be able to gather as much information as possible that allow you to assign scores to all items. General questions will be asked by content category, so it is important that the interviewer knows the tool very well. This also promotes a serene atmosphere and a better relationship between interviewer and interviewee. The usefulness of the assessment of adaptive behavior, although applied initially and predominantly in the case of the diagnosis of intellectual disability, has been recognized in several other types of clinical syndrome, in particular, in the case of autism spectrum disorder.

Social Inclusion

The social inclusion of people is to express all the potentials of each it covers all persons who may have life difficulties and situations of disability and concerns all those who participate in social life within a given context: to include means not to deny the fact that each of us is different or to deny the presence of disability or disability that must be treated appropriately, but it means shifting the focus of analysis and intervention from person to context, identifying obstacles and removing them.

Disability should not be understood as a disease (medical model), but as a social relationship between the characteristics of people and the environment (bio-psycho-social model). A way of thinking sanctioned first by the WHO and then by the UN in art. 3 of the Convention, where "full and effective participation and inclusion in society" is among the general principles. As in the example above, the class with a disabled child changes the curriculum according to to the needs of the child, it is built according to the needs it meets. The primary objective must be to promote decent living conditions and a system of genuine relations with people who have difficulties in their personal and social autonomy; so that they can feel part of the society where they can have recognized their role and their identity.

An important recognition was given by L.104/92 below

The Law 104/92

Law 104 is also called the "Framework Law for Assistance, Social Integration and the Rights of Disabled Persons". It was published in the Official Journal on February 17, 1992, "regulates all rights, benefits in terms of work, tax benefits and much more for people with disabilities" (Law 104/92 Disabled -Permits, News, Discounts, s.d.).

The aim of the regulation is to provide adequate support not only to the individual with a disability, but also to his or her family members, who take care of them. The legislator in art. 3, clarifies the definition of person with disability. "A disabled person is a person with a physical, mental or sensory handicap, stabilized or progressive, which is the cause of learning difficulties, of relationships or of occupational integration and which is likely to lead to a process of social disadvantage or exclusion".

Art. 1, however, lists the purposes of the law. The latter are:

To ensure "full respect for human dignity and the rights of freedom and autonomy of the disabled person" and to promote "full integration into the family, school, work and society";

21 Art. 20, paragraph 2, Law 2 April 1968, n. 482.

22 Art. 20, paragraph 3, law 482/68

23 Art. 3, first paragraph, Law 5 February 1992, n.104

Art. 1, however, lists the purposes of the law.

The latter are:

i. To ensure "full respect for human dignity and the rights of freedom and autonomy of the disabled person" and to promote "full integration into the family, school, work and society”.

ii. Prevent and remove "the disabling conditions which prevent the development of the human person, the attainment of the maximum possible autonomy and the participation of the disabled person in the life of the community, as well as the realisation of civil, political and patrimonial rights”.

iii. To pursue "the functional and social rehabilitation of persons with physical, mental and sensory disabilities" and to ensure "the provision of services and services for the prevention, treatment and rehabilitation of disabilities and the legal and economic protection of the person handicapped”.

iv. Prepare "measures to overcome the marginalisation and social exclusion of the disabled person".

The law in question deals with the protection of these people through some interventions, such as: "therapy and rehabilitation services, to allow the recovery of the disabled - if possible - or to facilitate their stay in his family context"; "support to the family, through information, psychological, economic support and involvement in social and health interventions"; "prevention actions directed at children (including in schools) to combat disability, limit discomfort, detect the occurrence of disabling diseases"; "interventions aimed at ensuring the health of the environment in the workplace, in the living environment and the prevention of accidents" (Law 104/92 Disabled - Permits, News, Facilities, s.d.).

The law in question deals with the protection of these people through some interventions, such as: "therapy and rehabilitation services, to allow the recovery of the disabled - if possible - or to facilitate their stay in his family context"; "support to the family, through information, psychological, economic support and involvement in social and health interventions"; "prevention actions directed at children (including in schools) to combat disability, limit discomfort, detect the occurrence of disabling diseases"; "interventions aimed at ensuring the health of the environment in the workplace, in the living environment and the prevention of accidents" (Law 104/92 Disabled - Permits, News, Facilities, s.d.).

For the support measures provided for by law, it is necessary for him to be satisfied with any form of disability. The assessment of disability is carried out by medical boards located at the local health units ASL. To access the law, you must submit an application. You must follow a specific procedure:

The assessment of disability is carried out by medical boards located at the local health units ASL. To access the law, you must submit an application. You must follow a specific procedure:

i. The attending physician must complete the introductory certificate, in which he inserts a series of information, such as: "the nature of the disabling infirmities, personal data, disabling pathologies from which the subject is affected" (Law 104/92 Disabled - Permits, News, Facilitations, s.d.).

ii. The document must be sent electronically to the INPS.

iii. The person will be invited to visit by the ASL Medical Commission, which will have to ascertain the disability. The visit can take place at the home of the individual, at the request of the doctor, either at the place established by the INPS computer system (Law 104/92 Disabled - Permits, News, Facilities)

iv. The document must be sent electronically to the INPS.

v. The person will be invited to visit by the ASL Medical Commission, which will have to ascertain the disability. The visit can take place at the home of the individual, at the request of the doctor, at the place established by the INPS computer system (Law 104/92 Disabled - Permits, News, Facilities).

A Possible Project of Life

Being handicapped, especially if serious, is a challenging and difficult challenge for parents as for teachers and operators, for those with a deficit, access to roles in different life contexts, respecting its functional and existential modes : student learning; in the world of work, assuming the role of a subject that contributes to production; in the cultural-recreational-social context, as a user and bearer of agency at the same time (Pavone, 2008) represents a sida linked to the possibility of knowing the specific individual characteristics, more or less easy.

The important problem is the development of a situation of hyperprotectionism and immobilism, the which manifests all its limits at the end of the education path of the obligation or even secondary, when the disabled student leaves the school institution and confronts the working/social environment, with serious risks of a sudden fall in planning, re-entry between the domestic walls and existential regression dynamics.

Looking at a well-integrated life plan means ensuring planning the promotion of a qualitative life in all the social environments of the which the person is to interact and at all ages» (34). Citing numerous research around the concept of quality of life throughout life, especially for the person with cognitive disabilities, but extendable to all those with a disability, Cottini highlights five relevant dimensions: physical, material, social, emotional, social functionality; as can be observed, the state of health, although in first place, not exhausting the complexity and richness of a being in the desirable world on the qualitative level [34]. Education allows us to imagine a process that, although the child is fragile and rough path is however projected to support it towards autonomy goals increasingly advanced existential [34].

Local authorities, cultural and leisure agencies present on the territory; the context of employment, where possible, the responses of adults, family members and experts, should be shared, to recompose the various sectoral readings in a design observation plan. This happens rarely; rather we observe how the different microsystems activated around its person: family-services, family-school, school-services, etc. remain isolated, except rare contact moments made mandatory by the procedures. Support for the educational and life project for the disabled benefits from the fact that all the members of the responsible team express their differentiated skills, parenting, health, education, education, care - in a synergistic perspective, sharing, for the purposes of the personalized plan. While this supplement of professional and human contacts can increase the rate of complexity, on the other hand, positively, can help to project educational and rehabilitation interventions in the area of being well for the disabled minor and his or her family, to keep alive the climate inside the treatment environment and to feed the availability to research: strategic conditions to counteract the depressive and renounced drifts always at the door [34].

Conflict of Interest

None.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- (2014) Manuale diagnostico e statistico dei disturbi mentali, Raffaello Cortina Editore.

- Cario, M (2014) Breve storia della disabilità. it, Anno XIV, N.7.

- Platone (2007) La Repubblica. Roma: Armando III: 409-410.

- Darwin, C (1967) L’origine della specie (1859). Torino, Bollati Boringhieri.

- Spencer, H (1851) Social statics, or the conditions conductive to human happiness, and the first of them specified. London: Williams & Norgate.

- Friedlander H (1997) Le origini del genocidio nazista: dall’eutanasia alla soluzione finale. Roma: Editori Riuniti.

- (1992) Legge 104/1992 G.U. Serie generale n.39 Suppl. Ordinario pp. 30.

- (2000) Legge 328/2000 G.U n. 265 Suppl: 186.

- (2009) Convenzione Internazionale sui Diritti delle Persone con Disabilità, ratificata dal Parlamento Italiano con L. G.U n.61 del (9).

- (2017) Programma di Azione Biennale per la promozione dei diritti e l’integrazione delle persone con disabilità Serie Generale n.289 del.

- (1999) Norme per il Diritto al lavoro dei disabili GU n.68 del Suppl. Ordinario pp. 57.

- (2000) Legge 8(328).

- (2001) International Classification of Functioning. Disability and Helath. World Health Organization.

- Carulla LS, Luis Salvador Carulla, Geoffrey M Reed, Leila M Vaez Azizi, Sally Ann Cooper, Rafael Martinez Leal, et al. (2011) Intellectual developmental disorders: towards a new name, definition and framework for “mental retardation/intellectual disability” in ICD-11. World Psychiatry 10(3): 175-180.

- Shevell M, Ashwal S, Donley DK, Flint, J, et al. (2003) Practice parameter: evaluation of the child with global developmental delay. Neurology 60(3): 367-380.

- Vianello, R (2015) Disabilità Con aggiornamenti al DSM-5. Bergamo, Edizioni Junior.

- DSM-IV-TR (2000) Manuale diagnostico e statistico dei disturbi mentali. Milano: Masson.

- Cornoldi, C (2017) L’intelligenza. Il mulino.

- Salthouse, TA (1991) Theoretical Perspectives on Cognitive Aging, Hillsdale, NJ Erlbaum.

- Verguts T, De Boeck PE, Maris E (1999) Generation speed in Raven’s progressive matrices test, Intelligence 27: 329-345.

- Doll EA (1965) Vineland Social Maturity Scale. Circle Pines: American Guidance Service.

- Grossman HJ (1973) Manual on terminology in mental retardation. Washington: American Association for Mental Deficiency.

- Grossman HJ (1983) Classification in mental retardation. Washington DC: American Association on Mental Deficiency.

- Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV (1984) Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. Circles Pines: American Guidance Service.

- Thompson JR, McGrew KS, Bruininks RH (1999) Adaptive and maladaptive behaviour: Functional and structural characteristics. In R.L. Schalock, Adaptive behavior and its measurement: Implications for the field of mental retardation. Washington: American Association on Mental Retardation.

- Tassè MJ, Schalock RL, Balboni G, Bersani H, Borthwick Duffy SA, et al. (2012) The construct of Adaptive Behavior: its conceptualization, measuremen, and use in the field of intellectual disability. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil 117(4): 291-303.

- Tassé MJ (2021) Adaptive Behavior and Functional Life Skills Across the Lifespan: Conceptual and Measurement Issues. Adaptive Behavior Strategies for Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities pp. 1-20.

- Balboni G, Belacchi C, Bonichini S, Coscarelli A (2016) Vineland-II. Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales Second Edition. Survey Interview Form. Standardizzazione Italiana [Vineland-II. Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales Second Edition. Survey Interview Form. Italian standardization]. Giunti OS, Firenze, Italy.

- Doll EA (1936) The Vineland Social Maturity Scale. Vineland, NJ: Vineland Training School.

- Pearson NA, Patton JR, Mruzek DW (2016) Adaptive behavior diagnostic scale: Examiner’s manual. Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

- Bruininks RH, Woodcock R, Weatherman R, Hill B (1996) Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised. Chicago, IL: Riverside.

- Balboni G, Tassè MJ, Schalock RL, Borthwick Duffy SA, Spreat S, et al. (2014) The Diagnostic Adaptive Behavior Scale: Evaluating its diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. Res Dev Disabil 35(11): 2884-2893.

- Schalock RL, Snell ME, Spitalnik DM, Spreat S, Tassé MJ (2002) Mental retardation: Definition, classification, and systems of supports (10th). Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation. (Trad. it., Ritardo mentale. Definizione, classificazione e sistemi di sostegno. 10a Edizione. Gussago (BS): Vannini Editrice, 2005.)

- Pavone M (2008) School and social integration, volume 7, number 2, The life project for the disabled student, Erickson Editore, Trento.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.