Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Assessment of the Response to the Cholera Outbreak in the Nkolndongo Health District (Cameroon)

*Corresponding author: Abdoulnassir Amadou, Public Health Departement, Faculty of Medecine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Yaoundé 1, Cameroon.

Received: July 29, 2024; Published: August 01, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.23.003087

Abstract

Introduction: The recent cholera outbreak in Cameroon had a high morbidity rate in the centre region overall and particularly the Nkolndongo Health District (HD), home to the Yaounde Central and Main Prisons, was the epicentre of the disease. This Health District has had a high case-fatality rate (3.8%), prompting questions about the implemented response mechanisms.

Methodology: We conducted a descriptive cross-sectional study with a mixed (quantitative and qualitative) data collection. The study lasted approximately 1 month and data were collected from 07 March 2022 to 30 May 2023. Quantitative data were obtained from the line list and the investigation form from the CTC of the Nkolndongo HD and the UTC of the Central/Main Prison of Yaounde. Qualitative data were obtained through a semi-directive interview.

ResultsThe most represented age group was between 20-29 years old, predominantly male, with nearly half of the patients living in prison. Nearly all patients presented with diarrhea and vomiting and over three-quarters required hospitalization. Regarding the response mechanisms implemented by the HD, several observations were made: inadequate coordination, particularly with limited engagement of the sectoral, shortcomings in hospital and community based surveillance, partial effectiveness of the epidemic control measures (communication, WASH, case management, etc); lack of effective free healthcare provisions and inadequate human and material resources.

Conclusion: The response to the cholera epidemic in the Nkolndongo HD encountered deficiencies at various levels, which likely contributed to the increased case-fatality rate. Addressing these aspects urgently with a view to improving the management of future public health emergencies.

Keywords: Assessment, response, cholera epidemic, Health district

Introduction

Cholera is an acute diarrhoeal infection caused by ingestion of food or water contaminated with the bacillus Vibrio cholerae. There are many serogroups of V. cholerae, but only 2 serogroups, O1 and O139, are responsible for epidemic outbreaks [1]. Approximately 20% of people infected with V. cholerae suffer from acute watery diarrhoea, with a further 20% likely to present with severe watery diarrhoea, many of whom also suffer from vomiting. If these patients are not treated promptly and adequately, the loss of body fluid and mineral salts can lead to severe dehydration, and death within hours [2]. Lethalitý in untreated cases can be 30-50%. However, treatment is simple (rehydration) and, if provided promptly and appropriately, the lethalitý should remain below 1% [1,3].

In Cameroon, the recent cholera epidemic reached all regions of the country with the exception of the Adamawa region. On May 30, 2023, only 3 regions remained active, namely the Centre, Littoral and South regions. With 22 active Health Districts (HD), 18,322 notified cases, 1,868 culture-confirmed cases (i.e. 10.2%); the number of deaths recorded was 426, i.e. a national case-fatality rate of 2.4%. The Centre region recorded an increase in the number of cases from the 13th week of 2023, making it the epicentre of the outbreak, with a cumulative total of 3,601 cases recorded, 136 deaths and a case-fatality rate of 3.8% [4]. The Nkolndongo Health District was one of the worst affected in the country, recording 446 cases, 17 deaths and a case-fatality rate of 3.8%; of these, 163 cases, including 7 deaths, came from the Yaoundé Central and Main Prisons, which are all located in this health district [4,5].

The Nkolndongo Health District, which is home to one of the country’s largest prison populations, has recorded several cases of cholera among prisoners. In view of the rapid increase in the number of cases and the high lethality rate (3.8%) recorded, which is above the threshold of 1% set by the World Health Organization (WHO). This led us to question the management of this outbreak, in view of the complexity linked to the above-mentioned particularity of this health district. We therefore set out to assess the quality of the response to the cholera outbreak in the Nkolndongo Health District. Specifically, we aimed to determine the profile of patients suffering from cholera, to describe the clinical presentation of the disease in the patients received and to evaluate the response mechanism in place.

Material and Methods

Type and Location of Study

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study. It was conducted using a mixed method (quantitative and qualitative). the Nkolndongo Cholera Treatment Centre (CTC) and the cholera treatment unit (CTU) of the Central prison of Yaounde.

Duration and Study Period

The study lasted approximately 1 month, and data were collected from 07 March 2022 to 30 May 2023.

Study Population

The quantitative data came from the line list and investigation forms of patients hospitalised for cholera treatment at the Nkolndongo CTC and the CTU of the Yaoundé Central Prison. Qualitative data were obtained through semi-directive interviews with key informants involved in the response at different levels (health district, CTC and community).

Type of Sampling

We carried out a non-probability sampling (consecutive and exhaustive).

Data Collection Tools

The following items were used for data collection: A data collection sheet, an interview guide, the line list of cholera patients and the investigation sheets.

Procedure

After obtaining the District's authorisation, we obtained the line list of patients with cholera and the investigation forms. The information was then collected using these tools, followed by a semi-structured interview and observation for the qualitative part.

Data Analysis

Quantitative variables were represented by the median and the interquartile range because they did not follow a normal distribution. Qualitative variables were presented in terms of frequency and proportions.

Data obtained at the end of the interviews was transcribed exhaustively from the audio recordings.

The quantitative data collected, after verification of the completeness of the information on the data collection forms, were entered into the Epidata software for statistical analysis using R studio version 4.2.2.

Ethical and Administrative Considerations

We obtained the approval of the Health District; the data collected in the registers were anonymous and their use was limited to the framework of the research. The participation of key informants was conditional by obtaining informed consent.

Results

In total, all 446 patients treated for cholera were included.

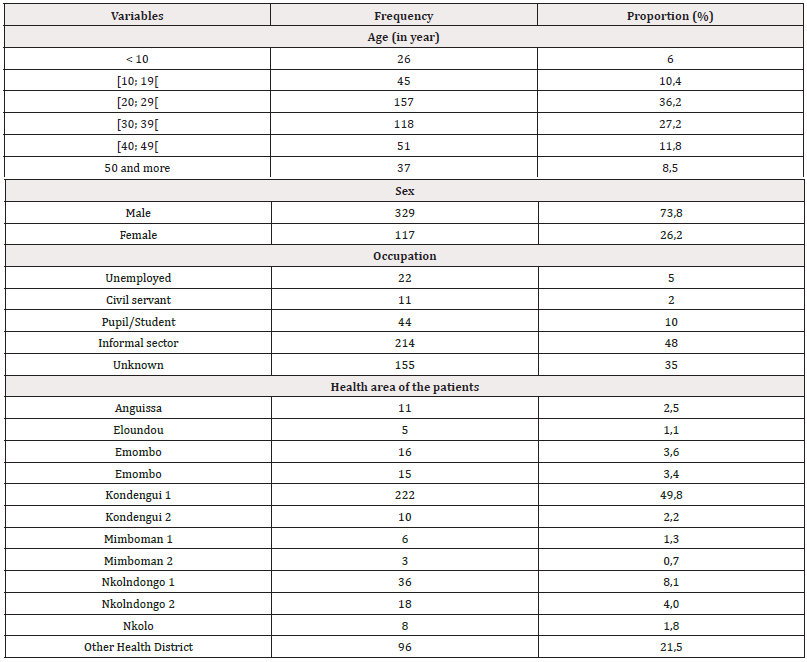

Patient Profile

The median age of the patients was 29 years, with an interquartile range of [22; 37]. The most common age group was between 20 and 29 years. Males predominated, with a sex ratio of 2.8. The most common occupation was the informal sector workers (48%). Nearly half of the cases came from the Kondengui 1 Health Area; almost all of these were inmates of the Kondengui Central Prison. Table 1 below provides an exhaustive presentation of the data summarised above:

Clinical Presentation of the Disease

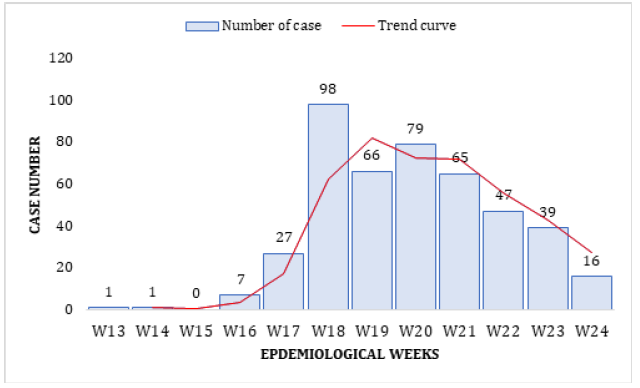

The Nkolndongo health district recorded a gradual increase in the number of cases from the 16th epidemiological week, reaching a maximum of 98 cases in the 18th week, of 2023 as shown in Figure 1 below:

The District's attack rate for the period concerned was 0.74 per 1000.

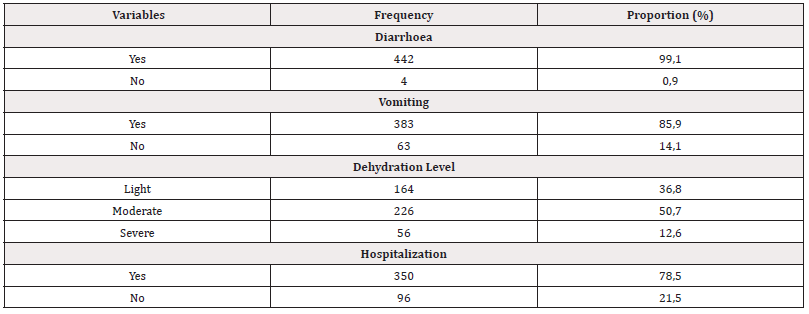

The symptoms most frequently observed in patients were diarrhoea (99.1%) and vomiting (85.9%). Nearly two-thirds of the patients received were moderately or severely dehydrated. A total of 78.5% were hospitalised, as shown in Table 2 below.

Assessment of the Response System

Coordination: Coordination of the response to cholera outbreak, which should be organised around the territorially competent administrative authority, was not always carried out, resulting in a lack of involvement of the sectors concerned by the response, as this source in the Health District told us: "We have been abandoned, it's as if the response to cholera outbreak only concerned the Ministry of Health... the municipality only intervenes when there are corpses to bury...". At the health district level, activities were poorly coordinated, with no incident management system in place and coordination meetings held at irregular intervals, sometimes weekly or monthly.

Epidemiological Surveillance: Active surveillance of cases at the health facilities and prison level was not effective, although some Community Health Workers (CHWs) were involved in notifying community cases. The involvement of dialogue structures in the response was not effective; the members of these structures were expecting remuneration from the Ministry of Health and its partners. According to this source, "the members of the dialogue structures are discouraged because they have not received any motivation since...". Nevertheless, the epicentre of the outbreak has been identified and is in the Etam Bafia neighbourhood, but cases are not always notified immediately, with some of them notified 1 or 2 days later.

Measures to Control the Epidemic (WASH and Communication): Sanitation was carried out as soon as a case of cholera was reported, initially by a Water, and Sanitation Hygiene (WASH) officer from the Health district. This activity was then decentralised to the health areas, where homes, public places, water supply points and corpses were systematically decontaminated.

Vaccination campaigns against cholera were organised and around 4,000 people were vaccinated. Communication activities were not very effective, either in the media or in the community. One source said: "Communication in the media was not effective ... and even awareness-raising was not really effective because we had few communications supports, particularly flyers, posters, etc.".

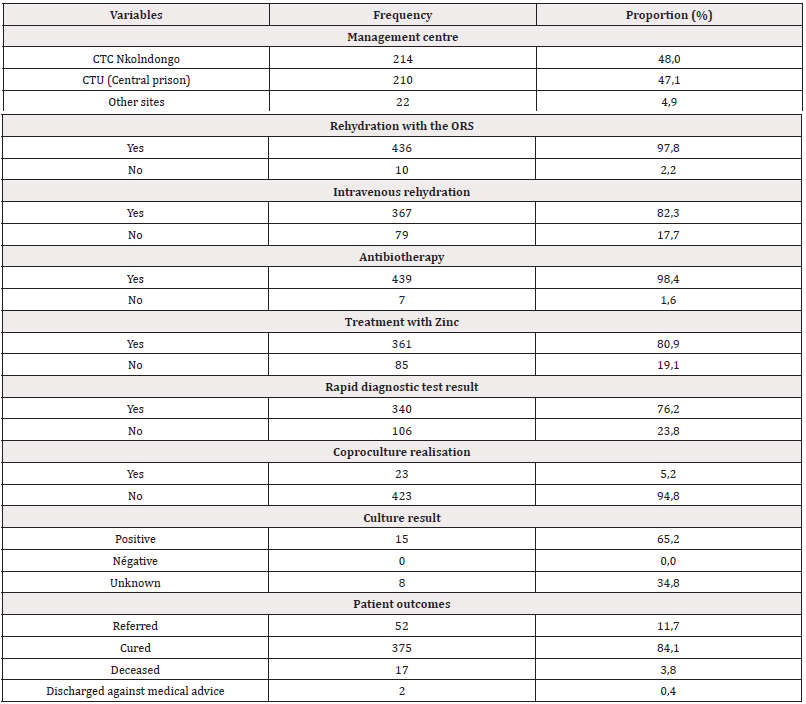

Diagnosis and Case Management: Case management in the centres was not free of charge. One of our key informants told us that: "when cases arrived, the first solutes was free, but once the emergency was over, the families was responsible for paying the rest ... we didn't have enough inputs". This source noted some shortcomings in the way the patients were treated: "At the beginning, we only had 3 beds at the CTC and 7 beds at the Prison's CTU ... At the prison, once the beds were occupied, others were lying on the floor". Another source claimed that some cases escaped the response system: " ... some corpses were recovered from the mortuary after the morticians had finished handling them". Almost all patients were treated either at the Nkolndongo CTC (48%), or at the Cholera Treatment Unit (CTU) at Kondengui Central Prison (47.1%). Oral rehydration with ORS was the most used treatment. The Rapid diagnostic test (RDT) was carried out in 76.2% of patients; only 5.2% of cases were confirmed by coproculture, and among them, the result was positive in 65.2% of cases, as shown in Table 3

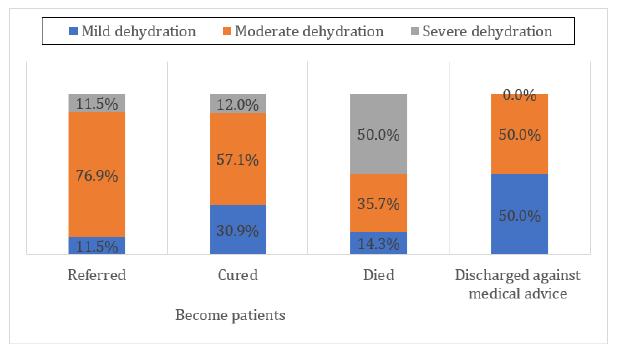

Among the patients who died, half were admitted with severe dehydration. Hospital deaths accounted for 82.3%, compared with 17.7% of community deaths (Figure 2).

Discussion

Patient Profiles

The age group most represented in this cohort was that of patients aged between 20 and 29, with a male predominance. This could be explained by the fact that people in this age group are the most professionally active, and by the fact that almost half of our study population is made up of people living in prisons, hence the male predominance also observed. These data are like those found at the national level, as described in the country's (Cameroon) national Situation report [5], but contradict the study carried out by Ohene et al in Ghana in 2 health districts, which found the 35 to 44 and 5 to 14 years’ age groups respectively to be the most represented [6].

Clinical Presentation of the Disease

The attack rate in our series was 0.74 per 1000 during the study period, which corresponds to the median attack rate (0.8 cases per 1000) found in the review carried out in 25 sub-Saharan African countries over a 10-year period (2010 to 2019) by Zheng et al [7]. An exponential increase in the number of cases between epidemiological week 13 and 18, from 1 to 98 cases, was observed, suggesting that there were several missed cases in the community, leading to an underestimation of the epidemiological data. Almost all the patients suffered from diarrhoea and vomiting. In addition, two-third of patients were admitted late to health facilities with moderate or severe dehydration, in contrast to the 59% who were admitted with mild dehydration in the national situation report [5]. Outpatient care was provided for 21.5% of these patients, which could be explained by the low capacity of the care units.

Assessment of the Response Mechanism (Coordination, Epidemiological Surveillance, WASH, Communication, Case Management)

Coordination of the response was inadequate due to the lack of sectoral involvement, and it was observed that coordination meetings were held more at health district level, with no fixed frequency and no response plan as recommended in the integrated disease surveillance guide [8]. This could be explained by the low availability of resources (human, material and financial) in the country's Health Districts, leading them to rely more on external resources from technical and financial partners via the intermediate level (Regional Delegation) or Central level (Ministry of Public Health). A qualitative study by Ngwa et al in Borno State, Nigeria, found that coordination was slow at the beginning of the response to the cholera outbreak in an Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp, although it improved later with the implementation of an incident management system with daily meetings aimed at coordinating the multisectoral response organised around a person designated by the government [9]. The results found by Ohene et al in Ghana in their evaluation of the response to a cholera epidemic in 2 Health Districts also showed good coordination with the involvement of the sectors and a reallocation of roles when necessary [6].

Active surveillance of cases in health facilities and at community level was inadequate, leading to late notification of cases and the recording of 3 community deaths. This could be explained by the fact that 97.8% of the health facilities in the district are private for-profit organisations and felt that they had little involvement in case surveillance and notification. The poor functioning of dialogue structures in the HD was also noted. The delay in case notification had also been described earlier in Cameroon by Ngwa et al in 2013 and in Ghana, where analysis of surveillance data at different levels [6,9] and community-based surveillance was sub-optimal with insufficient knowledge of the disease at community level [9].

Hygiene and sanitation measures implemented included disinfection (water supply points and corpses) and the provision of drinking water both in households and in prisons (Yaoundé Central Prison). However, these measures were insufficient, due to the demotivation of community and district actors, leading to a rapid increase in the number of cases. Another was the low level of involvement of sectoral bodies, in particular the municipal hygiene services and the Ministry of Water and Energy. This picture was different in the responses carried out in Borno State (Nigeria) and in Zambia, where the involvement of the various sectors was more remarkable [9,10]. Communication during the management of the epidemic was not very effective due to the poor availability of communication media, low awareness among CHWs and insufficient use of mass media (radio, television, etc.).

Case management, which should be free according to government regulations, was not always free due to a shortage of inputs, leading service providers to apply free treatment only to alleviate emergencies. There was also a shortage of beds and human resources in the case-management centres, which could explain the high case-fatality rate observed. The Ghana study found that there were no hospital deaths and that private health facilities were involved in case management [6]. In Nigeria too, patients were managed immediately after diagnosis, resulting in a case fatality rate (1.14%) in line with WHO standards [9].

Conclusion

The evaluation of the response to the cholera outbreak in the HD of Nkolndongo revealed : inadequate coordination, particularly with the low level of involvement of sectoral organisations, inadequate community-based surveillance; the effectiveness, albeit inadequate, of measures to control the epidemic (communication, WASH, case management, etc.); the lack of effective free treatment and the inadequacy of human and material resources, which probably contributed to the increase in the cholera attack and case-fatality rate in the health district concerned.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to the health staff and community members of the Nkolndongo Health District who supported us throughout the research process.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

No external funding was provided for this research.

References

- (2024) Organisation mondiale de la santé. Choléra - Situation mondiale.

- (2023) World Health Organization. Cholera.

- (2022) Organisation mondiale de la santé. Cholé

- (2023) Ministère de la santé Rapport de la situation à l’épidémie de choléra période du.

- (2024) Ministère de la santé Rapport Situation Choléra Cameroun N°43.

- Ohene SA, Klenyuie W, Sarpeh M (2016) Assessment of the response to cholera outbreaks in two districts in Ghana. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 5(1).

- Zheng Q, Luquero FJ, Ciglenecki I, Wamala JF, Abubakar A, et al. (20222) Cholera outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa during 2010-2019: a descriptive analysis. Int J Infect Dis 122: 215‑2

- (2024) Guide technique pour la Surveillance Intégrée de la Maladie et la Riposte au Cameroun fr. CCOUSP.

- Ngwa MC, Wondimagegnehu A, Okudo I, Owili C, Ugochukwu U, et al. (2020) The multi-sectorial emergency response to a cholera outbreak in Internally Displaced Persons camps in Borno State, Nigeria, 2017. BMJ Glob Health 5(1): e002000.

- Kapata N, Sinyange N, Mazaba ML, Musonda K, Hamoonga R, et al. (2018) A Multisectoral Emergency Response Approach to a Cholera Outbreak in Zambia: October 2017-February 2018. J Infect Dis 218(suppl_3): S181‑S183.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.