Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Former Foster Youth and Attachment Styles

*Corresponding author: Summer Bleich, University of Nebraska - Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

Received: June 20, 2024; Published: June 24, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.23.003036

Abstract

This study explored the connection between attachment styles and foster care experience. Specifically, this study aimed to assess the impact of the foster youth experience on attachment style development, in addition to happiness and life satisfaction. The literature shows that attachment styles can impact the trajectory of one’s life, especially if someone develops an insecure style. Attachment style development is greatly impacted by the individual’s primary caregivers. Negative experiences with their primary caregiver, such as abuse and neglect, often result in a child’s placement in foster care. This study surveyed adults who have spent at least one year in foster care and adults who have not spent any time in foster care. The analyses found that for both Life Satisfaction and Happiness measures, participants classified as Anxious Romantic attachment style scored significantly lower in Life Satisfaction and Happiness than those classified as Close, Depend, or Mixed. A significant interaction of Foster Care status and Romantic Attachment Style on Happiness was found as well. The highest Happiness scores were found for participants who were Former Foster Youth and who were classified as having a Close Romantic Attachment Style. The lowest Happiness scores were obtained by those who were classified as Anxious Romantic Attachment Style among both groups. Although limitations exist within this study, the findings underscore the need for more resources for the former foster youth population and their developed resilience, especially with the development of a Close Romantic Attachment Style.

Keywords: Foster youth, Attachment style

Introduction

“Loss of a loved person is one of the most intensely painful experiences any human being can suffer [1].” Consequently, a child who is in foster care experiences the loss of a loved one multiple times throughout their life, with the first time before the age of 18 years old, often at quite a young age. According to the Administration on Children, Youth and Families of the Children’s Bureau of Department of Health and Human Services, a foster youth is a dependent child who was removed from their family’s home. The removal from home can result from maltreatment, lack of care, or a lack of supervision from their caregiver [2]. As of 2016, over 400,000 children were reported to the Administration on Children, Youth, and Families as foster youths in the United States. At the age of 18, if a child is still considered a foster youth, they “age out” of such care and are often displaced from their temporary guardians’ homes and are left to figure out life on their own.

With a combination of an unstable childhood and the trauma of losing their natural family as well as their foster family, foster youth are at risk for various difficulties in life. These difficulties can range from mental health issues to impairments in occupational functioning [3]. There are many repercussions that can transpire from those early life experiences, specifically, unhealthy interpersonal relationships that can develop from insecure attachments [3]. Consequently, one of the most important factors for a child in foster care is the quality of the bond that is formed with caregivers.

Bowlby’s [4] attachment theory and Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) research suggest that the bond formed between the infant and primary caregiver has lasting effects on the individual’s interaction with the world [5]. Bowlby proposed that the developmental processes that mature in a bonding relationship are a complex integration of the infant-caregiver bond, the infant’s and caregiver’s genetics, the environment, and the caregiver’s own attachment history that produce the infant’s emerging social, psychological, and biological capacities in which they grow [4].

Ainsworth’s landmark Baltimore longitudinal study, Strange Situation Procedure (SSP), validated John Bowlby’s attachment theory and expanded what was known about patterns of attachment [5]. Ainsworth et al. explained that attachment is not inherited; rather, the capacity to attach is developed. This attachment is developed through transactional behaviors in an appropriate caregiving environment when a primary caregiver can provide a secure base for the infant to learn [5]. This unique and complex bond can only be understood when looking at all aspects that create it between the child and their biological mother. The bond between a child and their biological mother is important to grasp. Although many individuals who were not allotted the opportunity to bond with their natural caregiver are still able to develop secure attachments with others throughout their lives. However, this path is difficult. The attachment bond between an infant and biological mother begins immediately and continues to progress throughout childhood; thus, in circumstances in which this is disrupted, negative consequences can emerge quickly [5,6].

In Bowlby’s theory of attachment, the infant and their preferred person engage in a transactional relationship that creates a bond between them [6,7]. The transactional relationship is often developed by the behaviors that are seen between a child and parent, and these behaviors are characterized by gazing, smelling, tasting, touching, hearing, feeding, bathing, changing, and playing between the pair [6,7]. These behaviors are reinforced through the infant and parent’s interactions and continue to build the bond between them as the parent is able to scaffold and co-construct problem-solving skills. As the child continues to develop, the child is able to use their memory of the relationship and skills learned to feel a sense of security when it comes time to explore the world by crawling, walking, and talking [6,7]. Thus, the continual interactions of attachment behavior allow the infant to feel safe, secure and protected when they are in need. This ultimately gives the infant confidence in their caregiver that they will help the infant as they are progressing developmentally [4,6,7]. Ainsworth et al. suggested attachment is not necessarily the behaviors but rather a higher-level system that organizes the behaviors, the internal working model [5].

Moreover, according to Mash and Barkley, there are four basic functions of attachment [7]. As already indicated, the functions of attachment are

1. to provide a sense of security for the child and

2. to provide the child with a secure base so that they can explore and be protected when needed [7].

Additionally, two other functions of attachment are to

3. facilitate and develop the infant’s ability to regulate its own affect and arousal and

4. to be a vehicle for the infant to learn how to communicate and express feelings and emotions in an interpersonal relationship.

According to Marsh & Barkley, when an infant can fully feel secure and attach to their caregiver, the child is known to have a secure attachment [7]. However, when the infant and parent are not able to establish this type of bond, an insecure attachment style is assumed.

When a child is developing a secure attachment with their caregiver, as the child grows, they are likely to be confident and open to learning when exploring their environment. They are flexible and resourceful in their environment, and they are able to generalize the good relationship built with their parent to other relationships [6]. However, not all children are given the opportunity to establish a healthy attachment to their caregiver [1]. If a child and their preferred caregiver are not able to develop a secure attachment, three other attachment styles may develop [6]. These three are considered to be insecure attachments. One type of insecure attachment is termed avoidant attachment style, which is often created in children who are rejected or ignored by their mothers or in situations wherein mothers are often angry and intolerant of the infant’s distress [6]. Developing an avoidant attachment can lead the child to express higher levels of hostility and aggressive behavior, to be less likely to ask for help, and to withdraw or sulk.

Davies discussed that a second type of insecure attachment is termed ambivalent attachment style [6]. This type of attachment typically develops in children when they have mothers who are inconsistent in their responses to the child, which can lead the child to be conflicted about wanting contact with their mother and being angry [6]. This can lead to children who lack assertiveness, are socially withdrawn, use poor social skills, and have low levels of autonomous behavior [6,7].

The third insecure attachment style is called disorganized [6]. Disorganized attachment typically develops in children who have mothers with unresolved trauma, maltreatment experienced by their caregiver, or have a serious mental illness [6]. Implications from developing a disorganized attachment can lead to a child with poor self-confidence, poor academic achievement, increased aggressive behavior, and poor social skills [6,7].

Many children are not primarily raised by their biological parents but are raised by foster parents. This situation raises questions as to how being in foster care affects attachment. When a child is placed into protective custody (foster care), temporary arrangements are made for the child to live in a family’s home, providing temporary custody until the child can return to their biological caregiver, if ever [8]. Doyle discussed outcomes of children placed in the foster care system [8]. Sadly, foster parents do not always provide good care to their foster children. Approximately two million American families are investigated every year due to alleged abuse and neglect of their children, and approximately one million of those families are found to have abused or neglected their children. Out of these one million American families, approximately 10% of the children will be placed in foster care [8].

Statement of the Problem

Mash and Barkley asserted that too often, the early life experiences of infants tend to get “under the skin,” which can lead to mental and physical health problems as the infant grows older [7]. Additionally, Perry et al. stated that the experience of a traumatic childhood, whether it be neglect, abuse, or removal from parents, impacts the functionality of an individual [9]. Thus, the infant’s experiences become internalized and can develop into life-long traits that have implications for mental and physical health. Felitti and colleagues also facilitated research regarding implications of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) [10]. Their study highlighted the physical health implications of experiencing trauma in childhood and how the physiology of trauma and the stress response system can cause these individuals increased physical health problems and early death [10].

This study specifically focusses edon the negative implications that may result from a child spending time in foster care. With a combination of an unstable childhood and the trauma of losing their natural family as well as their foster family, they are at risk for various difficulties in functioning in life [11]. Children and adolescents placed in foster care are at risk for developing an insecure attachment with their caregiver(s) [11,12]. An insecure attachment can negatively impact a child’s development in various ways.

Due to the disruptions in their lives that most foster youth experience, such as the instability of caregivers, they are at risk of having difficulties in interpersonal relationships, especially regarding being able to form positive attachments [4,6,8].

This study was a quantitative study to explore the association between attachment styles of former foster youth in contrast to individuals who were not raised as a foster youth. Such comparisons allow for the identification of discrepancies that are unique to those raised in foster care. In addition, differences in the quality of interpersonal relationships, happiness, and life satisfaction were also examined. Participants for both groups were recruited via social media applications, such as Instagram and Facebook.

The Present Study

This study examined the relationships between having been in foster care, psychological difficulties, attachment styles (romantic and traditional styles), general life satisfaction, and the emotional state of happiness, specifically. The participants were individuals who had spent at least one year in foster care and individuals who had never spent any time in foster care. Participants were recruited via social media applications, such as Facebook and Instagram. The participants were asked to complete five self-report measures via SurveyMonkey, which assessed demographics, attachment styles (romantic and traditional), satisfaction with life, and level of happiness.

Based on Bowlby’s attachment theory [1,4,12] and the trauma of spending time in foster care, foster youth may be vulnerable to forming insecure attachments [2,6,13]. Insecure attachment styles make individuals vulnerable to developing psychopathology, interpersonal, behavioral, and emotional problems [6,9]. Therefore, this study utilized two different approaches to attachment style. One approach is the traditional categorization of an individual's general attachment style (Secure, Fearful, Preoccupied, Dismissive). An alternative conceptualization of attachment style focused specifically on attachment in a romantic relationship context was also used. This more narrow or focused way of conceptualizing attachment more specifically relates to a more intimate interpersonal relationship, the connection to having been in foster care, and the implications, if any, for general life satisfaction and happiness.

The two attachment measures were utilized to assess the attachment styles of the participants: Griffin and Bartholomew’s Relationship Scales Questionnaire and Collins’ Revised Adult Attachment Scale. Griffin and Bartholomew’s scale assessed participants’ attachment styles in a more traditional sense of secure, fearful, preoccupied and dismissing [14,15]. Griffin and Bartholomew’s questionnaire utilized Bowlby’s understanding of the internal working model to further understand and classify attachment styles for adults. Griffin and Bartholomew viewed these patterns of attachment as ways of “regulating the security of close relationships” in adulthood (1994a) [16]. The Secure style encompasses individuals who are “comfortable with intimacy and autonomy,” the Preoccupied style denotes individuals who are “preoccupied with relationships,” the Dismissing style indicates one is “dismissing of intimacy,” and Fearful represents individuals who are “fearful of intimacy” [16].

The traditional way of classifying attachment styles can be thought of as a generalized way or type of attachment. In contrast to the traditional format for classifying attachment styles, Collins developed a classification system specific to attachment styles in a romantic relationship [15]. The present version of this scale is called the Revised Adult Attachment Scale assesses attachment styles within a romantic relationship context. Individuals are asked to reflect on their past and current romantic relationships and answer these questions based on what they felt within those relationships. Three types of attachment styles are assessed with this questionnaire: Close, Depend, and Anxiety [15]. The Close style represents individuals who are “comfortable with closeness and intimacy.” The Depend Style represents those who feel they can depend on others. Last, the Anxiety style suggests individuals who are “worried about feeling unloved or rejection.” These romantic attachment styles are assessed on a 5-point Likert scale from 1, “Not at all characteristic of me,” to 5, “Very characteristic of me,” using 18 questions.

Hypotheses

The following null hypotheses were examined:

Hypothesis 1: Former foster youth will not have developed an insecure attachment style any more than youth who have not had foster care experience.

Hypothesis 2: Specifically, former foster youth will not have a disorganized attachment style.

Hypothesis 3: There will be no difference between former foster youth and individuals who were not in foster care on a level of happiness measure.

Hypothesis 4: There will be no difference between former foster youth and individuals who were not in foster care on the Satisfaction with Life measure.

Methods

Participants

This study included a total of 33 participants ranging in age 22-65. Eight of the participants were former foster youth who spent at least one year in foster care. The comparison group consisted of 26 non-former foster youth participants. Of the 33 participants, 27 identified as females, 5 identified as males, and one identified as another gender identity. The sexual orientation of the participants included 22 who identified as straight/heterosexual, five identified as lesbian or gay, three identified as bisexual, and three identified as other sexual orientations. As the last degree obtained, four obtained a high school diploma or GED, one obtained an Associate’s, 10 earned at least a Bachelor’s degree, and 18 received an advanced degree of either a Master’s or Doctoral level degree. The race/ethnicity of participants consisted of 23 White/Caucasian, six Hispanic/Latinx, three Black/African American, and one Asian/Asian American. Marital status included 15 single/unmarried, 15 married, and two were divorced, and one identified as separated.

The breakdown of attachment styles consisted of 15 close attachment styles within the Revised Adult Scale (RAAS), four Dependent attachment styles, nine Anxious attachment styles, and five participants endorsed at least two primary attachment styles. The Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ) endorsed five Secure, three Fearful, nine Preoccupied, 12 Dismissing, and four multiple primary attachment styles.

Participants were recruited via the first researcher’s personal social media platforms, Facebook and Instagram. The Participants Recruitment Online Post was posted on both platforms as a research opportunity concerned with former foster youth and attachment styles. Inclusion requirements for participants were former foster youth individuals who spent at least one year in foster care and individuals who had never spent any time in foster care. All participants had to be at least 18 years of age or older. Participants who were under 17 years old or younger were excluded from the study. Additionally, participants were not excluded based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or gender identity.

Measures

Screening and Demographic Questionnaires: Each participant was screened for appropriateness before participating in the study. The screening questionnaire consists of two parts and three questions in total. The purpose of the screening questionnaire was to rule out participants who are not at least 18 years old and assess which group the participant belonged in with the comparison group, consisting of non-former foster youth for comparison with the former foster youth participants.

Furthermore, the participants were then asked to complete a demographic questionnaire that consisted of 7-10 questions, depending on whether they were former foster youths or not. The questionnaire invited each participant to provide the following information about themselves: age, gender identity, sexual orientation, highest degree obtained, ethnicity, marital status, foster care status, and information regarding their experience in foster care, if relevant. Additionally, it should be noted that this demographic questionnaire was developed by the primary researcher.

Revised Adult Attachment Scale (RAAS): Collins’ Revised Adult Attachment Scale (RAAS) was used to examine the attachment styles of each participant [15]. The RAAS is an 18-item questionnaire consisting of three subscales designed to examine how an individual relates to their current or past romantic partner in terms of closeness and intimacy, dependability, and anxiety toward love and rejection. Participants are asked to rate on a Likert scale statements that assess their feelings about romantic relationships they have experienced. The Likert scale starts from 1, “Not at all characteristic of me,” to 5, “Very characteristic of me.”

The RAAS is scored by breaking up the participant's answers into the subscale on which the statement falls. Some answers need to be reversed score as well. Each of the three subscales should have six scores to be averaged to show a final score for each subscale. The highest subscale score designates the participant’s primary attachment style. For participants who had two primary attachment styles, a new attachment category was added (Mixed) to maintain the current sample size without losing data. The psychometrics for this scale indicates a high internal consistency. The scale’s developer computed Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient on the three subscales: close, depend, and anxiety. The internal consistency for the subscales is as follows: .80-.82 (Close), .78-.80 (Depend), and .83-.85 (Anxiety [15].

The Satisfaction with Life Scale: The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is a self-report measure that was used to examine each participant’s general satisfaction with their life [17]. The SWLS consists of five questions aimed to assess life satisfaction on a 7-point Likert scale. Thus, the scores from the scale can range from 5-35, with total scores of 5-9 resulting in a self-report of extreme dissatisfaction with one’s life. Furthermore, total scores of 31-35 indicate extreme satisfaction with one’s life, and a score of 20 represents a neutral stance toward one’s life satisfaction [17]. The psychometrics for this scale has shown a high internal consistency ranging from .79 to .89 and a high-test re-test reliability of .84 to .80 [17].

Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ): The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ) is a self-report measure used to assess the participant’s level of happiness [18]. The OHQ originated from the Oxford Happiness Inventory (OHI) and was designed to be “compact and easily administered” in comparison to the OHI [18]. The OHQ consists of 29 statements and asks participants to indicate how much they agree or disagree with a statement. The Likert scale is as follows: “1=Strongly Disagree, “2=Moderately Disagree”, “3= Slightly Disagree”, “4= Slightly Agree”, “5= Moderately Agree”, and “6=Strongly Agree”.

This questionnaire is scored by reverse scoring answers to statements 1, 5, 6, 10, 13, 14, 19, 23, 24, 27, 28, and 29, then adding up the answers and dividing the number by 29 (Hills & Argyle, 2002). Final scores can range from 1- 6, with scores between 1-2 indicating the individual is “not happy”, 2-3 “somewhat unhappy”, 3-4 “not particularly happy or unhappy”, 4 “somewhat happy or moderately happy, 4-5 “rather happy; pretty happy”, 5-6 “very happy”, and a score of 6 indicating the person is “too happy.”

Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ): Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ) is a self-report measure to assess adult attachment [14]. The RSQ contains 30 statements designed to assess attachment types: Secure, Fearful, Preoccupied, or Dismissing. The 30 statements are to be considered in the context of “which statement best describes your characteristic style in close relationships” within a Likert scale that starts at 1, representing “Not at all like me” to 3, “Somewhat like me” to 5, “Very much like me.’ This measure was scored by breaking up the questions into what attachment style is being assessed, then reverse scores the questions indicated, and finding the average of each style for each participant. Thus, the highest average score for the attachment types was designated as the participant’s primary attachment style [14]. For participants who had two primary attachment styles, another attachment category was added by the researcher (Mixed) to maintain the current sample size without getting rid of data. Psychometrics for this measure is unknown.

Procedures: Participants were recruited via social media platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram. The social media post requested that individuals participate in the research opportunity, and a link to the research was provided to SurveyMonkey. Those participants who clicked on the SurveyMonkey link were directed to the initial page introducing the research and the researchers responsible for this study. The participant was then directed to click “next” to continue participating in the study. The participants were then directed to the Informed Consent Form. The participants were then asked to read the informed consent and click “I agree to participate in this research project” or “I do not agree to participate in this research project”. Those participants who clicked “I agree to participate in this research project” were then directed to the next portion of the research process, screening.

On the next page, the participant was brought to the screening questionnaire (Appendix C), where they were asked the first part of the screening process to determine eligibility to participate, “Are you between the ages of 18- 65?”. If the participant clicked “yes”, they were then brought to the second part of the screening questionnaire that determined which research group they would be put into: the control group (non-former foster youth) or comparison group (former foster youth). The participants were asked, “Have you spent any time in foster care?” and “Have you spent at least one year in foster care?”. After the participants indicated their foster youth status, they were directed to click “next” to continue participating in the research study. However, if the participant clicked “no” to the first part of the screening process, indicating they did not meet the age requirement, they were directed to an Exit page.

The participant was then directed to the first of five questionnaires. The questionnaires were in the following order:

1. Demographic Questionnaire,

2. Revised Adult Attachment Scale (RAAS),

3. The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS),

4. Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ), and

5. Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ).

After completing the last measure, the participants were directed to the Debriefing Statement and then to a handout of mental health resources, which contained the Suicide and Crisis Life Lifeline and self-guided emotion regulation skills. The total time needed to participate in the research project was 20-30 minutes. Additionally, participants were not compensated for participating.

Results

The following statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS software package. Descriptive statistics were computed for all demographic variables. Statistical analyses were computed using ANOVAs and Pearson Correlations. There was a significant effect of Gender on Happiness scores (F(1,30)=5.528, p=.026). In general, women obtained higher Happiness scores (M=4.370, SD=.706) than men did (M=3.5, SD=.4950). There were no interactions of Gender with Attachment Styles; thus, all participants were used for the following analyses.

Last, the following null hypotheses were examined:

I. former foster youth will not have developed an insecure attachment style any more than youth who have not had foster care experience,

II. former foster youth will not have a disorganized attachment style,

III. there will be no difference between former foster youth and individuals who were not in foster care on a level of happiness measure, and

IV. there will be no difference between former foster youth and individuals who were not in foster care on the Satisfaction with Life measure. No significant differences were detected within the two groups, former foster youth and non-former foster youth. Thus, none of the null hypotheses were could be rejected.

Traditional Attachment Style, Life Satisfaction and Happiness

The primary variable of interest was whether the participant had ever been in foster care. In addition, of major interest was the relationship of attachment style to life satisfaction as an overall variable, and happiness as a specific emotional state. No significant relationships with Life Satisfaction or Happiness were obtained for the traditional classification of attachment style (Secure, Fearful, Dismissing or Preoccupied). In addition, there were no significant interactions of traditional attachment style with gender or foster care status on Life Satisfaction or Happiness scores.

Romantic Attachment Style, Life Satisfaction and Happiness

However, attachment style in regard to romantic relationships was found to be significantly related to Life Satisfaction and Happiness scores. Therefore, the basic statistical analysis consisted of using Foster Care (yes or no) and Romantic Attachment Style (4 types) as the other independent variable in 2 x 4 ANOVAs with Life Satisfaction and Happiness as the dependent measures.

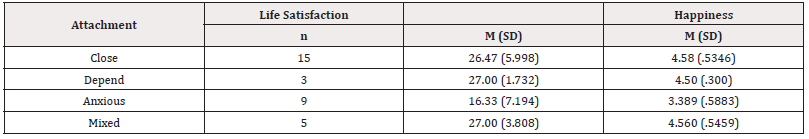

There was not a main effect of Foster Care on either Life Satisfaction scores (SWLS), nor on the Happiness measure (OHQ). There were significant main effects of Romantic Attachment Style on Life Satisfaction scores (F(3,25) = 4.676, p = .01) and on Happiness scores (F(3,25)=9.799, p= .000). The means and standard deviations for each Romantic Attachment Style for Life Satisfaction and Happiness scores are presented in Table 1. It can be seen in Table 1 that those with an Anxious Attachment Style within the romantic relationship context had lower scores on both Life Satisfaction and Happiness. However, as will be reported further below, and in Table 2, there was a significant interaction of Foster Care status and Romantic Attachment Style on Happiness scores, but not on Life Satisfaction Scores (Table 1).

Table 1: Means and Standard Deviations for main effect of Romantic Attachment Style on Life Satisfaction and Happiness Scores.

Further analyses were conducted comparing each of the Romantic Attachment styles with each other. For both Life Satisfaction and Happiness measures, LSD tests revealed that those classified as anxious scored significantly lower in Life Satisfaction and Happiness than those classified as Close, Depend and Mixed. All probability levels were at .01 or lower.

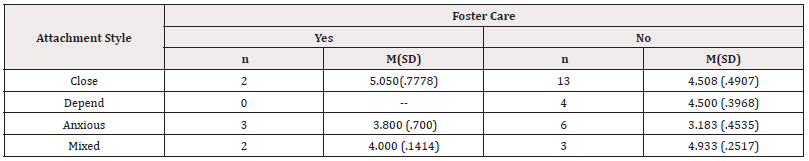

As indicated above, there was a significant interaction of Foster Care status and Romantic Attachment Style on Happiness scores (F(2, 25)=4.487, p=.022). Means and standard deviations for each Romantic Attachment Style for those who had been in Foster Care and those who had not been in Foster Care are presented in Table 2. It should also be noted that none of those participants who had been in Foster Care were classified as having Dependent Romantic Attachment Style. It should also be noted that the n for each of the combinations of Attachment Style and Foster Care status are small, especially for those who had been in Foster Care. Despite those limitations of small n, a significant interaction effect was obtained. As can be seen in Table 2, the highest Happiness scores were obtained by those participants who had been in Foster Care and who were classified as having Close Romantic Attachment Style. It can also be seen in Table 2 that the lowest Happiness scores were obtained by those who were classified as Anxious Romantic Attachment Style among both those who had been in Foster Care as well as those who had not been in Foster Care (Table 2).

Table 2: Means and Standard Deviations of Happiness Scores for Each Romantic Attachment Style for Those who had Been in Foster Care and Those who had not Been in Foster Care.

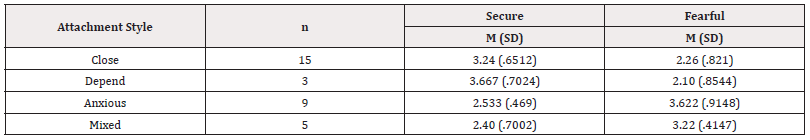

Relationship of Romantic Attachment Type to Traditional Attachment Style Sub-scores

Additional ANOVAs were performed using Foster Care and Attachment Style as the independent variables and the scores on Traditional Attachment Style sub-scale scores (Secure, Fearful, Preoccupied and Dismissing) as the dependent variable. An ANOVA was conducted using Foster Care status and Romantic Attachment Style as the independent variables and the scores on the traditional attachment styles (Secure, Fearful, Preoccupied and Dismissing) as the dependent variables. No effects were found for Foster Care status nor was the interaction significant, but there were significant main effects of Romantic Attachment Style on the Secure (F (3, 25) =4.351, p =.013) and Fearful (F (3, 25) =3.037, p=.048) subscales. The means and SDs for each of the Romantic Attachment Styles are presented in Table 3 for the significant main effects on Secure and Fearful sub-scales (Table 3).

Correlations

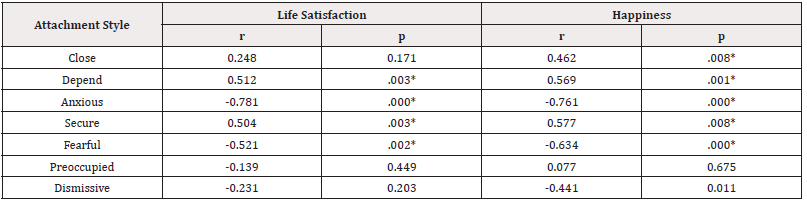

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to explore the relationships between Life Satisfaction scores and Happiness scores and traditional attachment styles and romantic attachment styles. Table 4 shows that Satisfaction and Happiness scores were highly correlated with each other (r = .772, p= .000). Thus, 59.6% of the variance in the correlation of Life Satisfaction and Happiness scores is accounted for by the correlation, meaning that approximately 40% of the variance is not accounted for in the high correlation of Life Satisfaction and Happiness scores and thus is accounted for by other factors not included in this study (Table 4).

Table 4: Correlations of Life Satisfaction Scores and Happiness Scores with Attachment Styles with Romantic Partner and with Traditional Attachment Styles.

Note*: p < .05.

As can be seen in Table 4, Life Satisfaction scores were significantly positively correlated with Depend Romantic Attachment Style (r=.512, p=.003) and with the traditional Secure Attachment Style (r=.504, p=.003). Additionally, Life Satisfaction scores were negatively correlated with Anxious Romantic Attachment Style (r=-.781, p=.000) and Fearful Traditional Attachment style scores (r= -521, p=.002). Happiness scores were positively correlated with a Close (r=.462, p=.008) and a Depend Romantic Attachment Style (r=.569, p=.001) and with a Traditional Secure Attachment Style (r=.577, p=.008), and negatively correlated with an Anxious Romantic Attachment Style scores (r=-.761, p=.000) and with traditional Fearful (r=-.634, p=.000) and Dismissive Attachment Style scores (r=.-.441, p=.011).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to quantitatively examine the attachment styles associated with having lived in foster care. Previous research has found that those who have experienced being removed from their biological caregiver and have had multiple caregivers are more likely to develop an insecure attachment style, which can have negative implications for future interpersonal relationships. It was expected that those who have lived in foster care for at least one year would have an insecure attachment style, and those who were not in foster care would have a secure attachment style. Additionally, it was expected that there would be differences between the two groups in the quality of relationships, happiness, and life satisfaction.

Romantic Attachment Styles, Life Satisfaction and Happiness

The results from the statistical analysis indicated that individuals whose primary way of relating to romantic partners in an anxious manner experience significantly lower levels of life satisfaction and happiness. Furthermore, data analysis also found former foster youth participants and romantic attachment styles showed a significant difference in happiness scores compared to the participants who had never been in foster care. Specifically, further analysis reported that former foster youth had the highest happiness scores compared to those who have close romantic attachment styles. The lowest happiness scores were reported from those participants who have not been in foster care and who also have an anxious romantic attachment.

These results may indicate that creating a close, intimate interpersonal relationship in adulthood may bring former foster youth more happiness than the general person due to possible lower expectations for interpersonal relationships or possibly because they have had to attain immense personal growth to reach a point in their lives where interpersonal relationships are valuable for them.

Romantic Attachment Styles and Traditional Attachment Styles

Pearson’s Correlation indicated various significant relationships with both attachment scales, life satisfaction and happiness scores. Life satisfaction scores were positively related to individuals who were identified to have depend or secure attachment styles. Thus, individuals who feel confident within interpersonal relationships also were satisfied with their life as well. Conversely, individuals who indicated life dissatisfaction and lower levels of happiness are associated with anxiety about being rejected or unloved (Anxiety) or fearful of intimacy or/and socially avoidant within interpersonal relationships (Fearful). Additionally, the higher the happiness score the higher the association with feeling comfortable with closeness and intimacy in relationships, feeling others are available/dependable, and feeling comfortable with autonomy.

This may indicate that the development of interpersonal relationship, secure or otherwise can be associated with a person’s overall level of happiness and how satisfied they feel about their life. Thus, Bowlby’s premise of attachment styles and how they are developed may have a more meaningful impact on one’s life than just specific experiences.

Clinical Implications

Important information to underscore from these results about individuals who have spent time in foster care is the resilience some hold. It is striking that the highest Life Satisfaction and Happiness scores were obtained by those who had experienced foster care and had been able to develop a Close Romantic Attachment Style. Despite experiencing the trauma of foster care and potentially other traumatic experiences, some former foster youth participants were able to develop styles of relating to others that were quite strong and healthy and compare well with those who would be expected to have had significantly less interpersonal traumas that would make secure relationships difficult. It is important that clinicians are able to recognize that at least some foster care youth have significant strengths despite early life trauma.

Simultaneously, it is important for clinicians to be alert to foster care youth who exhibit an Anxious Romantic Attachment style. These individuals, similar to those who have not experienced foster care, are at risk for reduced life satisfaction in general and happiness in particular. Thus, based on the findings in this study, clinicians should be alert for clients who struggle with an anxious romantic attachment style. These individuals are especially at risk for having difficulties achieving a general sense of satisfaction with their lives, which manifests specifically in a limited sense of happiness. Due to this, the development of psychopathology may be a focus for mental health clinicians, specifically a depressive disorder or an anxiety disorder, whether the potential client is a former foster youth or not. If the client attending counseling services is a former foster youth, including trauma-informed care services and assessing the extent of the trauma experiences using the ACEs measures may be helpful.

If traumatic experiences appear to be the etiology of the former foster youth’s psychopathology, depending on how the client’s symptom presentation, utilizing a Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) approach to treatment may be an ideal treatment approach due to its evidence-based background. Additionally, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) could be another treatment approach to target the client’s trauma. Non-former foster youth treatment approaches could differ due to differing etiology of the psychopathology. Another evidence-based treatment approach to a depressive or anxiety disorder could be cognitive behavioral therapy and utilizes specifically Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT). However, approaches to treatment with non-former foster youth could differ depending on the client's and clinicians’ preferences.

The hindrance of trauma for secure attachments for some former foster youth participants can be resolved to the extent to which healthy interpersonal relationships, happiness, and living a satisfying life are possible. Clinicians working with current and former foster youth need to be able to recognize when the experience of foster care has laid a foundation of anxiety about attachments, hindering the ability of the individual to form close romantic attachments and thus limiting their satisfaction with their life and in achieving a sense of happiness. While the traumatic feelings deserve attention, the consequent problems with forming attachments need to be specifically addressed, as even when the pain of trauma is alleviated, the difficulties in forming a close attachment cannot be assumed to automatically dissolve or be transformed into an ability to trust and relate in productive, relationship enhancing behaviors and attitudes. Clinicians working with former foster youth may need to spend more time in the rapport-building phase of treatment and/or allow for more surface-level treatment such as psychoeducation and skill building and practice in therapy as opposed to emotion-focused or trauma-focused interventions.

Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

There are several limitations to this study. The first limitation is the relatively small sample obtained. Thus, the small sample limits the ability to generalize these results to other former foster individuals. The small sample also limits the sensitivity of the study to detect differences, although it was possible to obtain several statistically significant differences. Additional limitations include the limited reach for potential participants due to recruiting through personal social media platforms. Utilizing personal social media platforms may influence the variety of participants sampled, thus limiting the generalizability of the results.

Another area for improvement in this study is the limits and weaknesses of the measures used. Although the measures authors suggest a high internal consistency and good test-retest reliability, other psychometric properties of the measures used are unknown. Lastly, another limitation could be the small sample size precluding being able to obtain significant interaction effects of the various demographic variables with the main variable of this study (foster youth experience and type of attachment style).

Future studies should attempt to conduct some of the research methods and procedures in person if possible. Researchers for the current study utilized social media and Survey Monkey to recruit and administer measures; due to the sensitivity of the population being researched, making an in-person connection with a former foster youth participant may help increase the likelihood of that participant completing the measures. When evaluating the progress of participants completing the research via SurveyMonkey, it was observed that many participants completed the demographic questionnaire and disclosed a former foster youth status but still needed to finish the entirety of the study. The comparison group of former foster youth participants showed a similar number of participants until further examination of the Survey Monkey results. Thus, additional avenues to increase the likelihood of participants completing the research should be considered.

Furthermore, future studies should work to increase participant recruitment. This could be improved by extending the availability of participants to complete research via Survey Monkey and utilizing additional social media and connecting platforms to recruit participants. If funding is possible for future studies, providing an incentive to complete research could help increase the number of participants as well. Additionally, steps should be taken to utilize more psychometrically sound measures and possibly add measures or questionnaires that gather a better understanding of the participant's journey to a secure attachment style, if possible. Thus, understanding their therapy experience(s), if any, which therapeutic modalities were used, what the participant's protective and risk factors were, and assessing for the participant’s Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Essentially, understanding the middle part of each participant’s journey.

Summary and Conclusions

This study assessed former foster youth and non-former foster youth for attachment styles and found no significant results surrounding traditional attachment styles (Secure, Fearful, Preoccupied, and Dismissing) singly, nor with gender, nor with foster care status, in relationship to life satisfaction, or happiness. Although traditional attachment styles and former foster youth status were the main focus of this research, other significant results were found regarding former foster youth status and attachment styles within romantic relationships. Individuals who endorsed former foster youth status and were classified as having a Close Attachment style in romantic relationships scored the highest Happiness scores, with the lowest Happiness scores obtained by those who were classified as having Anxious Romantic Attachment Style regardless of foster care status. These findings suggest that for basically “normal,” young adults, issues related to romantic attachments are highly relevant to ultimate life satisfaction and happiness, and that anxiety as a basic romantic issue is anathema to such positive feelings about life.

Additionally, no participants in this study who had been in Foster Care were classified as having Dependent Romantic Attachment Style. Within the context of Collin’s Revised Adult Attachment Scale [15], Dependent attachment styles are seen as a more adaptive style as you often feel you can depend on others to be available when you need them to. Thus, although a former foster youth may feel comfortable with closeness and intimacy in romantic relationships, it is still difficult for many former foster youths to be comfortable with the idea of dependency in a close relationship. Such a finding requires much more research.

“From the cradle to the grave,” Bowlby’s words symbolize the lifelong impact one’s attachment style can have. [4]. Attachment styles develop through a feedback loop pattern between the primary caregiver and the child. Children, for better or worse, unconsciously adjust their response/behavior to ensure their caregiver’s acceptance and, in turn, have their needs met to varying degrees. Individuals who have experienced trauma, such as the removal from their biological parent’s home and placed in foster care, often unconsciously adjust their response to their primary caregiver in a way to cope with their environment. These ways of coping can result in insecure attachment styles that may lead to further struggles later on in life, such as interpersonal concerns and the development of psychopathology.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Bowlby J (1980) Attachment and loss, volume III: Loss, sadness and depression. Basic Books.

- (2014) Child Welfare Information Gateway. Parenting a child who has experienced trauma.

- Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau.

- (2018) https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/child-trauma.pdf

- Laghi F, Baiocco R, Cannoni E, Norcia A, Baumgartner E, et al. (2013) Friendship in children with internalizing and externalizing problems: A preliminary investigation with the pictorial assessment of interpersonal relationships. Children and Youth Services Review 35(7): 1095-1100.

- Bowlby J (1982) Attachment and loss, volume I: Attachment (2nd). BasicBooks.

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall SN (2015) Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation (Classic Edition). Taylor& Francis Group.

- Davies D (2011) Child development: A practitioner’s guide (3rd ). The Guildford Press.

- Mash EJ, Barkley RA (Eds.) (2014) Child psychopathology (3rd). Guildford Press.

- Doyle JJ (2007) Child protection and child outcomes: Measuring the effects of foster care. Am Econ Rev 97(5): 1583-1610.

- Perry BD, Pollard RA, Blakley TL, Baker WL (1985) Childhood trauma, the neurobiology of adaption, and “use-dependent: development of the brain: How “states” become “traits.” Infant Mental Health Journal 16 (4): 271-291.

- Felitti VJ, Anada RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, et al. (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med 14(4): 245-258.

- Holtan A, Handegard BH, Thornblad R, Vis SA (2013) Placement disruption in long-term kinship and nonkinship foster care. Children and Youth Services Review 35(7): 1087-1094.

- Bowlby J (1973) Attachment and loss, volume II: Separation, anxiety, and anger. Basic Books.

- (2016) American Academy of Pediatrics and Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption. Parenting after trauma: Understanding your child’s needs.

- Griffin D, Bartholomew K (1994b) Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ).

- Collins N (1996) Revised Adult Attachment Scale (RAAS).

- Griffin D, Bartholomew K (1994a) Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67(3): 430-445.

- Pavot W, Diener E (1993) The Satisfaction with Life Scale [Measurement instrument]. Psychol Assessment 5(2): 164-172.

- Hills P, Argyle M (2002) The oxford happiness questionnaire: A compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 33(7): 1073-1082.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.