Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Fundamental Conclusions on Research into the Anatomy and Organization of the Helical Heart

*Corresponding author: Jorge Carlos Trainini, President Perón Hospital, Buenos Aires, Argentina. University National of Avellaneda, Argentina.

Received: August 13, 2024; Published: August 20, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.23.003125

Introduction

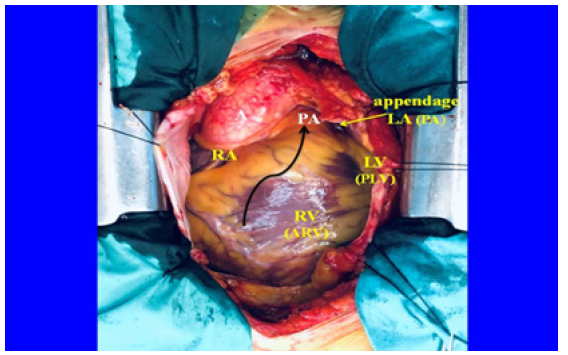

The heart is a network composed of structures that became integrated as evolution made this development necessary for adaptive demands. From the circulatory duct of annelids to the mammalian four-chamber heart different components were added to the organization to build a functional pattern that satisfied a circulation adapted to aerial life. Isolated, these components had different structures and functions, but, as a whole, they became complementary in the organizational cardiac function. Only in the physiological pattern there is a sense for each structure. The three-dimensional structural arrangement that the four chambers have forces a nomenclature in keeping with their helical reality: hence the proposition to name them as right atrium, antero-right ventricle, postero-left ventricle and posterior atrium (Figure 1)[1]. These concepts, presented here, were carried out through research that included fresh hearts from bovids, pigs and humans. Anatomical, histological and histochemical studies were carried out. The heart was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Histology was performed with hematoxylin-eosin, Masson's trichrome staining technique, and four-micron sections. 10% formalin was used as buffer. Immunolabeling (s100-neurofilaments) was also done. The endo- and epicardial electrical activation sequence of the left ventricle has also been studied in patients using three-dimensional electroanatomical mapping with a Carto navigation and mapping system that allows a three-dimensional anatomical representation, with activation and electrical propagation maps. All this extensive work was communicated through recently published texts (Figure 1)[2-5].

Figure 1: Photograph of an “in situ” human heart in a patient prior to heart surgery. The proposed nomenclature is shown between brackets). References. A: aorta; PA: pulmonary artery; RA: right atrium; LA (PA): left atrium (posterior atrium); LV (PLV): lessssft ventricle (posterior-left ventricle); RV (ARV): right ventricle (antero-right ventricle). The black arrow indicates the sense of the counterclockwise helical torsion of the venous circuit around the aorta.

Development

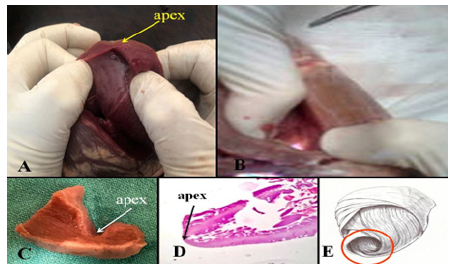

The anatomic-physiological study starts with the description of the continuous myocardium (Figure 2). Its spatial helical configuration is consistent with the mechanical torsion evidenced by the different segments constituting its structure. In the histological analysis, the sequence of the unfolded myocardium shows a linear orientation according to the continuity of the segments, which when coiled acquire their three-dimensional spatial configuration. In the natural state of the coiled myocardium, the segments overlap in the left ventricle and in the septum [6-9]. The right ventricular free wall, with a half-moon shape and formed by just one segment, consists of only the right segment of the continuous myocardium. Consequently, the left ventricular thickness is twice that of the right ventricle. No segment of the sequential histology of the continuous myocardium explored in our investigations presented a mesh arrangement. The anatomical and histological studies of the myocardium in its helical organization were confirmed through investigations with echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging and cardiac modeling studies (Figure 2)[10,11]. In normal conditions, the apex, space between the descending and ascending segments, has the property of annular narrowing (sphincter-like mechanism) to support the retrograde intracavitary pressure produced by blood ejection. It produces almost no measurable displacement (Figure 3), remaining practically immobile during the whole cardiac cycle, exerting only a certain pressure on the chest wall [12,13]. The base of the heart is the one that moves, by descending (systole) and ascending (suction). The apex shows the myocardial helical arrangement, as at this site it transforms its direction from descending into ascending. The apex cul-de-sac is lined on the inside by the endocardium and on the outside by the epicardium with few intermediate muscle fibers, which is evidenced through positive transillumination, which allowed us to develop a surgical technique to reduce the size of the ventricle. left [14-16].

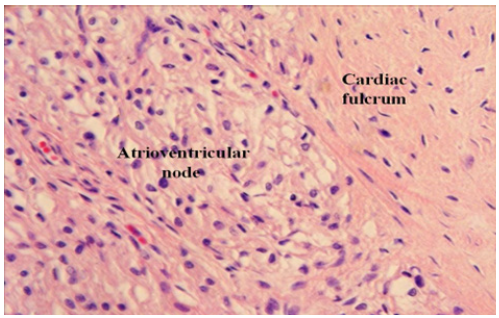

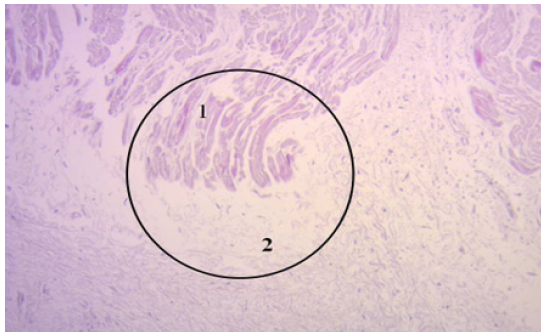

A crucial point in the investigation was the discovery of a myocardial support (Figure 4) that we have called cardiac fulcrum. Anatomically, the heart cannot be suspended and free in the thoracic cavity, because it would be impossible for it to eject blood at a speed of 200cm/s. Therefore, it should have a point of attachment, which, once found, was termed cardiac fulcrum (supporting point of a lever) [17-21]. In this supporting point the myocardial fibers are inserted in its structure, of a connective, chondroid or osseous nature according to the specimens analyzed. In our investigations, all the hearts (bovine, pig and human) studied with anatomical and histological techniques confirmed this attachment (Figure 5).

Figure 2: Myocardium unfolded in all its extension. PA: pulmonary artery; RS: right segment; LS: left segment; DS: descending segment; AS: ascending segment; A: aorta. The below inset shows the three-dimensional helical arrangement of the continuous myocardium. The red circle determines the cardiac apex.

Figure 3: A: Cardiac apex. B: Positive transillumination in the apical cul-de-sac shows that there are practically no muscle fibers in this region. C and D: Macro and microscopic detail of the apex showing the endocardium attached to the epicardium, with almost no muscle layer, presenting 10% thickness in relation to the adjoining myocardium. E: The drawing of the helical-coiled continuous myocardium reveals the nature of the apex, which is made up of a fragile area given the change in orientation of the descending segment to ascending segment. A and B: bovine heart. C: adult human heart. D: 16-week human embryo.

Figure 4: Cardiac fulcrum in the bovine heart. The microscopic field shows trabecular bone tissue with osteologic segmental lines corresponding to the cardiac fulcrum. H&E technique (40x).

The fibers giving origin and end to the myocardium, attach to the fulcrum, leaving the rest of muscle structure free in the mediastinum. The adjacency of the cardiac fulcrum to the AV node, surrounded by a rich plexus of neurofilaments, leads us to consider an anatomical electromechanical unit, in which the stimulation energy and muscle mechanics participate [22]. The effectiveness achieved by placing the pacemaker lead in the vicinity of the right ventricular outflow tract supports the findings of this investigation (Figures 6,7).

Figure 6: Human heart. Magnification 600 x. The image shows the fulcrum contiguous to the Aschoff-Tawara AV node.

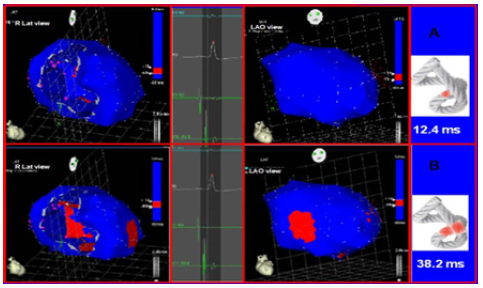

The three-dimensional anatomical composition of the heart is consistent with the sense of activation of the different continuous myocardium segments, whose overlapping is essential in the left ventricle [23]. The stimulus runs through its muscular pathways, but to fulfill the function established by the helical arrangement it must fundamentally activate the left ventricular segments, descending and ascending, simultaneously, and in opposite directions [24]. The stimulus transmission between them generates the necessary ventricular torsion that prompted the expression like “wringing a towel” to facilitate its physiological understanding (Figure 8). This study was the first in humans. This functionality enables ventricular ejection with the necessary force in a limited time span to sufficiently supply the whole organism. Regarding its power, ventricular torsion belongs almost exclusively to the left ventricle.

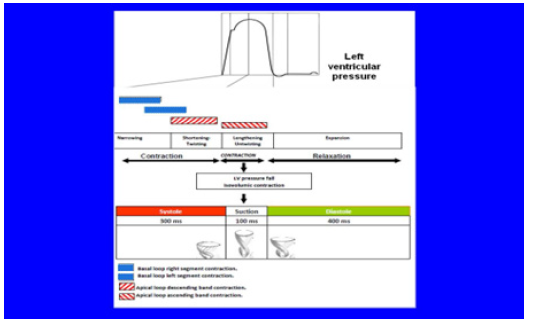

After systole, the subsequent suction phase of the heart is possible through the very small pressure difference with the periphery. Neither can it be passive. The detorsion of the heart in the first 100ms of diastole, a phase we have called Protodiastolic Phase of Myocardial Contraction, generates the negative intraventricular force for blood suction in the left ventricle, even in the absence of the right ventricle, as confirmed in our investigations. This suction phase (“suction cup mechanism”) is active with energy consumption and implies a three-time cardiac cycle: systole, suction and diastole. The investigations performed (Figure 9) confirm that there is an active coupling phase inserted between systole and diastole with muscular contraction, energy consumption, and significant drop of intraventricular pressure. This effect generated by active suction draws blood towards the left ventricular chamber by a difference in pressure in relation to the periphery [25-27].

Figure 7: 27-week infant heart. The image shows nervous trunk hypertrophy in the cardiac fulcrum (black circles) adjacent to the AV node. HEx200. The inset illustrates the thick nervous trunk in the cardiac fulcrum confirmed by immunohistochemistry for S-100.

Figure 8: Onset of left ventricular activation. The left panel shows the depolarization of the interventricular septum, corresponding to the descending band. In the right panel, the ventricular epicardium (ascending band), has not been activated yet. B. Simultaneous band activation. Activation progresses in the left ventricular septum through the descending band (longitudinal activation) and simultaneously propagates to the epicardium (transverse activation) activating the ascending band.

In the circulatory cycle, there is only one period that can achieve negative pressure in the ventricular chambers at a definite time. This phenomenon is produced during the Protodiastolic Phase of Myocardial Contraction in which pressure drops up to -3 mmHg, according to our measurements (Figure 10). Between aortic valve closure and mitral valve opening, and hence between pulmonary valve closure and tricuspid valve opening, there is a sudden drop of intraventricular pressure with energy consumption, that can reach negative values. It is during this phase when muscular contraction of the final portion of the ascending segment in its insertion in the cardiac fulcrum - myocardial support- produces myocardial lengthening-detorsion with closed ventricular chambers. This septal contraction, due to its ventricular interdependence determines, as we shall see, the Protodiastolic Phase of Myocardial Contraction in both ventricles with the generation of a suction process [28].

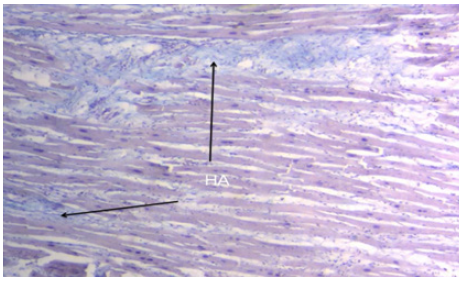

The opposite sliding of the left ventricular internal segments relative to the external ones to achieve ventricular torsion produces friction between them. It is reasonable to assume that from a physical point of view this friction implies resistance to movement. As expressed by the law of Newton, friction limits its continuity. There would be high energy consumption if the myocardium did not have a spongy system formed by Thebesian and Langer venous conduits, with an antifriction lubricating system. In the histological studies of this spongy network and its conduits, hyaluronic acid (Figure 11), which runs throughout the myocardial muscle width, was the antifriction effect found [29].

Figure 9: A. Late activation of the ascending band. At this moment, which corresponds to approximately 60% of QRS duration, the Endo cavitary activation (descending band) is already complete. The distal portion of the ascending (epicardial) band depolarizes later. This phenomenon correlates with the persistence of the band contraction in the initial phase of diastole. B. Final Activation. In the right panel, the projection was changed from left anterior oblique to left posterolateral, showing very late activation of the distal portion of the ascending band.

Figure 10: Diagram of the circulatory system with pressure values throughout its course. Pressures are expressed in mmHg. References: LVs: LV in systole; LA: left atrium; LVd: LV in diastole; PC: pulmonary capillary; RV: right ventricle; RA: right atrium; SC: systemic capillary.

Figure 11: Interstitial space between cardiomyocytes showing hyaluronic acid (HA) stained with Alcian blue technique (15x) (adult human heart).

The helical organization of the continuous myocardium (structure) and ventricular torsion (function) lead the intraventricular hematic content to form a small whirlwind (Figure 12), explained by the physical laws of dissipative structures [30] This vortex, because of ventricular torsion, allows blood to be ejected with the necessary force to achieve the circulatory needs of the different organs [6,7].

The initial asynchrony in semilunar valve opening between the right ventricle and the left ventricle explains the necessary functional complementarity of the circulatory movement, and provides the rationale for the anatomic-physiological structure of the helical continuous myocardium that constitutes the heart [28-31] The systemic and pulmonary vascular beds are connected in series to form a continuous circuit throughout the active phases of each ventricle, ejection and suction, since while the former generates positive pressures, the latter tends to negative ones. As each ventricle has only one chamber to fulfill two active phases of opposite function, suction and ejection, and a passive phase of diastolic filling, we must analyze that to complete a unidirectional circulatory system an asynchronous necessary between these phases to allow blood to circulate in one sense and with an effective sequence. Despite systemic and pulmonary circulations seem independent circuits, the synchronized activation of both ventricles between ejection and suction agrees with the acceptance of the active suction concept they present, as supported by recent research studies.

Thus, two subsystems are formed in the circulatory system, in which ejection and suction of the two ventricles act in this alternate complementarity, with both phases in active mode, with energy consumption and muscle contraction; a) Systemic subsystem: left ventricular ejection+ right ventricular suction; b) Pulmonary subsystem: right ventricular ejection+ left ventricular suction. Regarding cardiac mechanics, the use of equations based on the concept of energy (integrated variables) in a ventricular chamber is more evident than simply expressing function in terms of a pressure variable. The concept of blood pressure is determined by the properties of the vascular system and the heart capacity. Although this concept is correct, the notion that stroke volume is synonymous with the functional capacity of the heart is apparent. For example, the right ventricle and the left ventricle eject similar volumes, but their energies are different. Hypothetically, if the aortic diameter is reduced, stroke volume decreases. This implies that volume changes according to the resistance, so stroke volume is not an independent value. Stroke volume reflects the capacity of the heart as a function of two independent variables: output energy and systemic vascular resistance. According to these considerations it would be more logical to speak of ejective cardiac energy as a parameter that summarizes cardiac power to which non-independent variables would concur. In this model, energy consumption is prolonged from systole to the suction period, while only during the diastolic relaxation phase there is no energy expenditure. This concept is essential to consider a suction cardiac energy that takes place in the Protodiastolic Phase of Myocardial Contraction (Figure 13). This phase can become a promising clinical indicator, as left ventricular energetic suction is the continuity link between the pulmonary and systemic circulations. In the process of studying cardiac energy, suction energy and ejective energy should be assessed as more reliable indices of ventricular function.

In this investigation there is coherence between structure and the organizational function of the heart. The description of the continuous myocardium, from its support (cardiac fulcrum) (Figure 14) to the intraventricular vortex, explains its high mechanical efficiency and also the therapeutic procedures that have been used in clinical practice without a thorough understanding of their physiological mechanisms, such as right ventricular exclusion procedures, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, ventricular containment, ventricular resynchronization, univentricular mechanical support and left ventricular repair techniques.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Trainini J, Lowenstein J, Trainini A, Beraudo M, Wernicke M, et al. (2022) Carreras Costa F, Elencwajg B, Bastarrica ME. The helical heart and its implication on the resulting spatial anatomic arrangement of its chambers. Rev Argent Cardiol 90: 444-447.

- Trainini JC, Elencwajg B, López Cabanillas N, Herreros J, Lago N, et al. (2015) Basis of the New Cardiac Mechanics. The Suction Pump. 112.

- Trainini J, Lowenstein J, Beraudo M, Trainini A, Mora Llabata V, et al. (2019) Myocardial Torsion. Ed Biblos Buenos Aires Argentina.

- Trainini JC, Lowenstein JA, Beraudo M, Mora Llabata V, Wernicke M, et al. (2022) Fulcrum and Torsion of the Helical Myocardium. Editorial Biblos Buenos Aires 7(1).

- Trainini J, Lowenstein J, Beraudo M, Valle Cabezas J, Wernicke M, et al. (2023) Anatomy and Organization of the Helical Heart. UNDAV Ed Buenos Aires Argentina.

- Mora Llabata V, Roldán Torresa I, Saurí Ortiza A, Fernández Galera R, Monteagudo Viana M, et al. (2016) Correspondence of myocardial strain with Torrent-Guasp’ s theory. Contributions of new echocardiographic parameters. Rev Arg de Cardiol 84: 541-549.

- Mora V, Roldán I, Romero E, Saurí A, Romero D, et al. (2018) Myocardial contraction during the diastolic isovolumetric period: analysis of longitudinal strain by means of speckle tracking echocardiography. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 5(3): 41.

- Nakatani S (2021) Left ventricular rotation and twist: why should we learn? J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 19(1): 1-6.

- Poveda F, Gil D, Martí E, Andaluz A, Ballester M, et al. (2013) Estudio tractográfico de la anatomía helicoidal del miocardio ventricular mediante resonancia magnética por tensor de difusió Rev Esp Cardiol 66(10): 782-90.

- Valle J, Herreros J, Trainini J, García Jimenez E, Talents M, et al. (2017) Three-dimensional definition of Torrent Guasp´s ventricular muscle band and its correlation with electric activation of the left ventricle (abstract). XXIII Congreso SEIQ, Madrid, España BJS 105: s2.

- Trainini JC, Herreros J, Elencwajg B, Trainini A, Lago N, et al. (2017) Myocardium dissection. Rev Argent Cardiol 85: 40-46.

- Torrent Guasp F, Buckberg G, Carmine C, Cox J, Coghlan H, et al. (2001) The structure and function of the helical heart and its buttress wrapping. I. The normal macroscopic structure of the heart. Seminars in Thorac and Cardiovasc Surg 13: 301-319.

- Trainini JC, Beraudo M, Wernicke M, Carreras Costa F, Trainini A, et al. (2022) Anatomical Investigation of the Cardiac Apex. Rev Argent Cardiol 90: 118-123.

- Matsui Y, Fukuda Y, Suto Y, Hidetoshi Yamauchi, Bin Luo, et al. (2002) Overlaping cardiac volume reduction operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 124(2): 395-397.

- Menicanti L, Marisa Di Donato (2002) The Dor procedure: What has changed after fifteen years of clinical practice. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 124(5): 886-890.

- Trainini JC, Andreu E (2005) Does surgical reverse remodeling of the left ventricle have clinical significance? Rev Argent Cardiol 73: 44-51.

- Trainini JC, Lowenstein J, Beraudo M, Wernicke M, Trainini A, et al. (2021) Myocardial torsion and cardiac fulcrum (Torsion myocardique et pivot cardiaque). Morphologie 105(348): 15-23.

- Best A, Egerbacher M, Swaine S, Pérez W, Alibhai A, et al. (2022) Anatomy, histology, development and functions of Ossa cordis: A review. Anat Histol Embryol 51(6): 683-695.

- Moittié S, Baiker K, Strong V, Cousins E, White K, et al. (2020) Discovery of os cordis in the cardiac skeleton of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Sci Rep 10: 9417.

- Sosa Olavarría A, Martí Peña A, Martínez MA, Zambrana Camacho J, Ulloa Virgen J, et al. (2023) Trainini cardiac fulcrum in the fetal heart. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet 69(4).

- Trainini JC, Beraudo M, Wernicke M, Carreras Costa F, Trainini A, et al. (2022) Evidence that the myocardium is a continuous helical muscle with one insertion. REC: CardioClinics 57(3): 194-202.

- Trainini J, Wernicke M, Beraudo M, Cohen M, TraininiI A, et al. (2023) Cardiac Fulcrum, its Relationship with the Atrioventricular Node. Rev Argent Cardiol 91: 429-435.

- Trainini JC, Elencwajg B, López Cabanillas N, Herreros J, Lago N, et al. (2015) Electrical Propagation in the Mechanisms of Torsion and Suction in a Three-phase. Rev Argent Cardiol 83: 416-428.

- Torrent Guasp F, Kocika MJ, Corno A, Masashi K, Cox J, et al. (2004) Systolic ventricular filling. Eur J Cardio-thorac Surg 25(3): 376-86.

- Trainini JC, Trainini A, Valle Cabezas J, Cabo J (2019) Left Ventricular Suction in Right Ventricular Dysfunction. EC Cardiology 6: 572-577.

- Trainini J, Elencwajg B, Herreros J (2017) Activation Times in the Ventricular Myocardial Band. J Cardiol Cardiovasc Ther 4(3): 555638.

- Trainini J, López MPH, Bastarrica ME, Trainini A, Cabezas JV, et al. (2024) Mechanisms of action of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Quantum J Medical Health Sci 3(2): 73-83.

- Trainini J, Valle Cabezas J, Beraudo M, Elencwajg B, Wernicke M, et al. (2024) Ventricular Complementarity. I J cardio card diso; unisciencepub.com 5(2): 1-14.

- Trainini J, Beraudo M, Wernicke M, Carreras Costa F, Trainini A, et al. (2023) The hyaluronic acid in intramyocardial sliding. REC: CardioClinics 58(2): 106-111.

- Trainini J, Lowenstein J, Beraudo M, Wernicke M, Valle Cabezas J, et al. (2021) Physis of the ventricular vortex in dilated cardiomyopathy. Advancements in Cardiovascular Research 3(3): 315-321.

- Mangione S, Sullivan P, Michael MD, Wagner MS (2022) Diagnóstico Fí Secretos Elsevier Ed.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.