Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Introduction of “Patient Safety Angels” in Tertiary Medical College Hospitals by Training Interns and 4th Year Medical Students on the Detection and Reporting of Suspected Adverse Drug Events

*Corresponding author: Iftekhar Hossain Chowdhury, Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacology, Mugda Medical College, Dhaka-1214, Bangladesh.

Received: July 26, 2024; Published: August 01, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.23.003088

Abstract

Objective: Adverse Drug Event (ADE) is the unintended response to a drug considered as one of the important causes of morbidity and mortality and adding to overall healthcare costs. The success of pharmacovigilance programs depends on the participation of doctors in detecting, managing and reporting ADEs. But, in Bangladesh, doctors are not sufficiently aware of the significance of ADEs, and the number of ADE reporting is very poor.

Methods: A total of 219 4th year medical students and 225 intern physicians were recruited in this study and structured questionnaires were provided to them and were categorized into two groups- control and intervention. Among the 4th year students, 108 were controlled and 111 were intervention group and among the interns, 111 were controlled and 115 were intervention group. Baseline and post-interventional data for ADE detection and reporting were conducted by the cross-sectional survey. A set of educational interventions were formulated and delivered to the students and interns of the intervention group. The number of ADE reports submitted by the hospitals under study was obtained from the DGDA. The effect of educational intervention on interns was assessed by counting the number of ADE cases and reports and comparing them between the control and intervention groups.

Results: After 4 months of intervention, 36 cases of ADE were reported from the intervention group. ADE reporting to the DGDA remained unchanged in the control group hospitals [from 0% (0/400) to 0% (0/400)], but increased significantly (p<0.05) in the intervention group hospitals [from 0% (0/400) to 9.0% (36/400)]. The distinction between control and intervention was also significant (p<0.05). As a result, ADE detection and reporting increased in hospitals in the intervention group.

Conclusion: By addressing ‘patient safety angels’ this study motivates undergraduate students and interns for ADE detection and reporting and also ensures patient safety which can make a valuable clinical contribution to hospital care.

Keywords: Adverse drug event, Pharmacovigilance, Adverse drug reaction

Abbreviations: ADE: Adverse Drug Event; ADR: Adverse Drug Reaction; DGDA: Directorate General of Drug Administration; BSMMU: Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University; IRB: Institutional Review Board

Introduction

Medicines can treat or prevent diseases by producing therapeutic effects but can also produce unwanted or adverse effects [1]. No medicine is ever risk-free. The safety of medicines has been a major concern involving healthcare delivery systems globally [2]. When a medicine is first launched half of the risks are known and recorded [3]. The remaining risks are detected in the next 10-15 years through post-marketing surveillance. ADE has been compared to the tip of the iceberg by some author as it represents minor component of a significant catastrophe [4]. Pharmacovigilance compares the risks associated with various medications, identifying risk variables in particular, and evaluating both the efficacy and the medicinal product risk. In order to ensure the safe and effective use of medications and to track the results before prior actions, it provides timely communication and suggestions to regulatory authorities, clinicians, and users [5]. In every country, ADE monitoring is needed because of- differences in production and consumption of medicine, and dissimilar genetics of the people from one country to another

The main cause for ADE under reporting- Lack of knowledge about the reporting process, lack of time, lack of competence and training among health care professionals [6,3]. Various techniques to enhance ADE reporting have been developed throughout the years with varying degrees of success such as, Translation of ADE reporting forms in local language (Bangla), Educational intervention among key prescriber in different level of healthcare facility. ADR reporting training for medical students should be provided in undergrad and be strengthened during internships [7,8]. It was recommended that, by adding Pharmacovigilance to the undergraduate curriculum and once again during internship and residency, medical students’ knowledge could be boosted [9]. Although medical students acknowledge the value of ADR reporting and declare their intention to do so, they lack the pharmacovigilance expertise required to manage ADRs. A pharmacovigilance program’s success depends on the active participation of healthcare professionals like doctors, pharmacists, and nurses. ADE detection and reporting are a part of patient safety. In the socio-cultural context of Bangladesh, where there are the youngest physicians in the hospital who are interns, if they are addressed as “Patient Safety Angels”, their responsibility to ensure patient safety will be improved, and patients’ respect for them will also increase, as a result they will be honored. The present study was designed to encourage interns and 4th-year MBBS students about patient safety through ADE detection, documentation, and record-keeping as “Patient Safety Angels” and to increase medical students’ and interns’ pharmacovigilance knowledge and skill so they can recognize, handle, and report Adverse Drug Events (ADEs) in their future practice.

General Objective

To evaluate the impact of training conducted among 4th-year medical students to increase their knowledge and attitude about Adverse Drug Events (ADEs) detection and reporting.

To evaluate the impact of training conducted among intern physicians to increase Adverse Drug Events (ADEs) detection and reporting.

Materials and Methods

The study was formative interventional research. Regarding the comparison of sets of data, it was a before and after study. The protocol was reviewed and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of BSMMU issued a clearance Letter Memo No. BSMMU/2022/610. The study was conducted at four tertiary level medical colleges and hospitals from January 2021 to September 2023.Dhaka Medical College Hospital and Ad-Din Women’s Medical College Hospital were in control group. Z H Sikder Women’s Medical College Hospital (ZHSWMCH), Colonel Malek Medical College Hospital (CMMCH) were in intervention group. Interns who reported ADE without prescription image and Interns who reported ADE that was diagnosed in outpatients of studied hospitals not eligible for study participation. A total of 219 4th year medical students and 225 intern physicians were recruited in this study and structured questionnaires were provided to them, of which 207 4th year medical students and 216 interns responded completely to the survey and were categorized into two groups- control and intervention. Among the 4th year students, 108 were controlled and 111 were intervention group and among the interns, 111 were controlled and 115 were intervention group. Baseline and post-interventional data for ADE detection and reporting were conducted by the cross-sectional survey (Figure 1).

A set of educational interventions (Lecture and practical class) were formulated and delivered to the students of the intervention group and another set of educational interventions (workshop, focus group discussion, key informant interview) was formulated and delivered to the interns of the intervention group along with suspected Adverse Drug Events reporting form. Treatment sheets from each hospitalized patient at the hospitals under study were, collected, recorded, and reviewed for the detection of ADEs during the study period. The number of ADE reports submitted by the hospitals under study was obtained from the Directorate General of Drug Administration (DGDA). A standard procedure was used to assess the causality and severity of the reported cases of suspected adverse events. The intervention group received repeated follow- up visits to determine the outcome. The effect of educational intervention on interns was assessed by counting the number of ADE cases and reports and comparing them between the control and intervention groups.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done by Microsoft Office Excel 2013. A significant p-value is <0.05.

Result

Proportion of Detection of Cases of Suspected Adverse Drug Events in Hospitalized Patients of the Studied Hospitals (Baseline and after 4 Months)

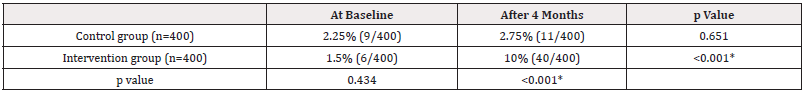

Table1. Shows after 4 months of educational intervention, the detection of cases was increased in the control [from 2.25% (9/400) to 2.75% (11/400)] and intervention [from1.5 % (6/400) to 10 % (40/400)] group hospitals. The difference was statistically significant (p<0.05) in the intervention, and also in the control and intervention groups (p<0.05). The difference was not statistically significant in control group (p>0.05) (Table1).

Table 1: Proportion of detection of cases of Suspected Adverse Drug Events in hospitalized patients of the studied hospitals (Baseline and after 4 months).

Proportion of Reporting of Cases of Suspected Adverse Drug Events to DGDA During the Study Period (Baseline and after 4 Months)

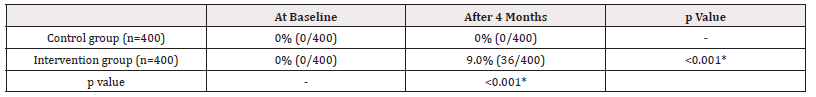

Table 2. Shows that, at baseline, none of the cases of ADE were reported to DGDA, both from control 0% (0/400) and intervention group 0% (0/400). But after 4 months of intervention, 9.0% (36/400) of ADE were reported from the intervention group and the difference was statistically significant in the intervention group and also in the control and intervention groups (p<0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2: Proportion of reporting of Cases of Suspected Adverse Drug Events to DGDA during the study period (Baseline and after 4 months).

Assessment of Knowledge and Awareness of 4th year Medical Students about ADE Detection and Reporting after 2 Months of Intervention

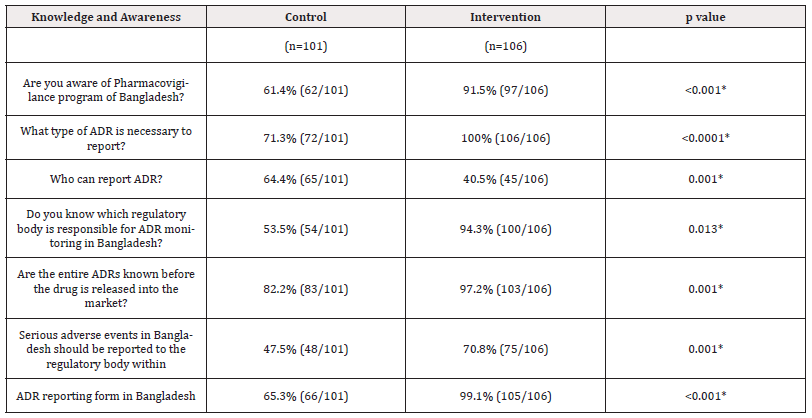

Table 3. Shows that significant differences were observed between the responses of the control and intervention groups after 2 months of intervention. The response was observed to be higher in the intervention group than in the control group and the difference was observed to be statistically significant (p≤0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3: Assessment of knowledge and awareness of 4th year students about ADE detection and reporting after 2 months (n=207) of intervention.

Assessment of Attitude of 4th year Medical Students of the Studied Hospitals about ADE Detection and Reporting after 2 Months

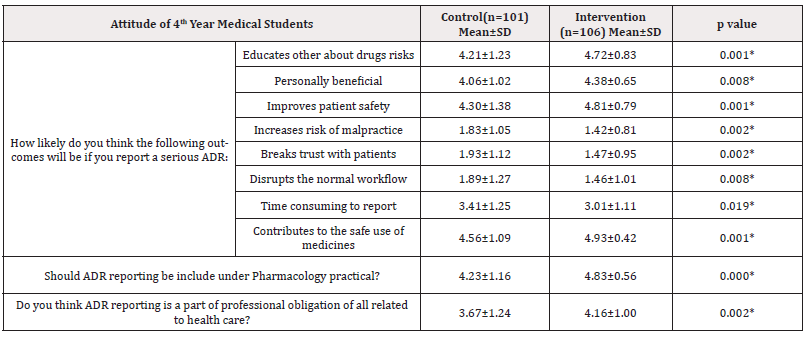

Table 4. Shows that according to the response of 4th year medical students, their attitude on ADE detection and reporting was changed after intervention in comparison to control group and the difference was statistically significant (p <0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4: Assessment of attitude of 4th year medical students about ADE detection and reporting after 2 months (n=207) of intervention.

Assessment of Knowledge and Awareness of Intern Physicians about ADR Detection and Reporting after 2 Months of Intervention.

Table 5. Shows that significant differences were observed between the responses of the control and intervention groups regarding knowledge and awareness of intern physicians about ADE detection and reporting after 2 months of intervention. The response was higher in the intervention group than in the control group and the difference was observed to be statistically significant (p ≤0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5: Assessment of knowledge and awareness of intern physicians about ADE detection and reporting after 2 months (n=210) of intervention.

Assessment of Perception, Practice, Experience and Training of Intern Physicians Towards ADE Detection and Reporting after 2 Months of Intervention

Table 6. Shows that the majority of the interns of the intervention group 90.1% (100/111) mentioned that they received training on the detection and reporting of ADE, where as in the control group, none of the participants received any training. Another important cause, problem with diagnosing ADE 9% (10/111) which was not significant with control group (p>0.05%), 8.2% (9/111) think reporting form is not available, problem of confidentiality with patient’s data 7.2% (8/111), these were significant with control group (p<0.05%) (Table 6).

Discussion

In light of the aforementioned findings, the mentor of this research developed an educational package of interventions for the interns with the intention to enhance ADE detection and reporting. After 4 months of intervention from baseline, a change in the detection of ADE was seen in the control group but was not statistically significant. The proportion of detected cases of ADE in the intervention group hospitals increases remarkably, from baseline following the initial 4-month intervention period. The difference was statistically significant both in the intervention and also in comparison to the control group. The present study also revealed that a significant difference was observed in the intervention group in comparison to the control group regarding ADE reporting after 4 months of intervention. Reporting of detected cases of ADE to DGDA was increased in the intervention group and was statistically significant after 4 months of intervention from baseline. But in the control group, no change has been observed regarding ADE reporting. All the reports were submitted by the intervention group hospitals. The previous study that was conducted in the Netherlands shows that the significant increase (by 300%) in the number of ADE reports following the monitoring of ADR by the medical students [10]. A tenfold increase in the rate of ADE reporting after educational intervention was observed in the previous study that was conducted in Portugal [11] and another study also revealed improvement in ADE reporting after educational intervention [12].

In this study we’ve tried to evaluate the knowledge and attitude of the 4th year medical students through a questionnaire before and after intervention. We found that the knowledge of the students about ADE detection and reporting has been enhanced and attitude changed significantly after intervention. After 2 months of intervention, their knowledge and awareness improved remarkably and their attitude changed which was statistically highly significant but the control group remained unchanged. In a previous study [13], after 2 months of intervention, the majority of the interns in the intervention group mentioned that they received training on the detection and reporting of ADE, whereas in the control group, none of the participants received any training. Previous research has yielded similar results [14,3]. Regarding their experience of encountering any patient with ADE during their training period, the intervention group was observed to have higher levels of experience than the control group, and this difference was statistically significant.

Conclusion

From the findings of the study, we can conclude that educational interventions that have been formulated and implemented in accordance with the needs of the Uppsala Monitoring Centre have been found to be successful in enhancing knowledge and changing attitudes among fourth-year medical students as well as in improving the detection and reporting of ADE by intern physicians.

Limitations

It was carried out in a very short period of time, so the sustainability of the change after intervention could not be assessed.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Prof. Dr. Layla Afroza Banu, Professor and Head of the Department of Pharmacology, Z H Sikder Women’s Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Author Contributions

FM: Conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources and software, validation, writing original draft, editing, and review. SR: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, validation, writing original draft, editing, and review. IC: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing original draft, editing, and review. SI: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing original draft, editing, and review. MB: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing original draft, editing, and review. SS: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing original draft, editing, and review. KN: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing original draft, editing, and review. SS: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing original draft, editing. SA: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing original draft, editing, and review. AS: Conceptualization, methodology, writing original draft, editing, and review.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work is funded by own funding research.

References

- Edwards IR, Aronson JK (2000) Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. The lancet 356(9237): 1255-1259.

- Helali AM, Iqbal MJ, Islam MZ, Haque M (2014) The evolving role of pharmacovigilance and drug safety: The way forward for Bangladesh. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 6(4): 31.

- Johora F, abbasy AA, Sakin SA, Mahboob S, Mahmud A, et al. (2020) Knowledge, Attitude and Practice towards Pharmacovigilance and Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting among physicians working in Rural Healthcare Facility. Journal of Brahmanbaria Medical College 2: 2-9.

- Amran MS (2021) Adverse drug reactions and pharmacovigilance. InNew insights into the future of pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety 3.

- Nasir M, Zahan T, Farha N, Chowdhury AS (2020) Acquaintance, approach and application of pharmacovigilance: questionnaire-based study at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Dhaka. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 9(10): 1497.

- Palaian S, Ibrahim MI, Mishra P (2011) Health professionals' knowledge, attitude and practices towards pharmacovigilance in Nepal. Pharmacy practice 9(4): 228s.

- Sivadasan S, Chyi NW, Ching AL, Ali AN, Veerasamy R, et al. (2014) Knowledge and perception towards pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reaction reporting among medicine and pharmacy students. World J Pharm Pharm Sci 3(3): 1652-1676.

- Bajaj JK, Rakesh K (2013) A survey on the knowledge, attitude and the practice of pharmacovigilance among the health care professionals in a teaching hospital in northern India. J Clin Diagn Res 7(1): 97-99.

- Bagewadi HG, Rekha MS, Anand SJ (2015) A comparative evaluation of different teaching aids among fourth term medical students to improve the knowledge, attitude and perceptions about pharmacovigilance: An experimental study. Int J Pharm Res 5(4): 91-97.

- Reumerman MO, Tichelaar J, Richir MC, van Agtmael MA (2021) Medical students as junior adverse drug event managers facilitating reporting of ADRs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 87(12): 4853-4860.

- Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT, Polónia J, Gestal Otero JJ (2006) An educational intervention to improve physician reporting of adverse drug reactions: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. JAMA 296(9): 1086-1093.

- Tabali M, Jeschke E, Bockelbrink A, Witt CM, Willich SN, et al. (2009) Educational intervention to improve physician reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in a primary care setting in complementary and alternative medicine. BMC Public Health 9: 274.

- Reumerman M, Tichelaar J, Richir MC, van Agtmael MA (2021) Medical students as adverse drug event managers, learning about side effects while improving their reporting in clinical practice. Naunyn-schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol 394(7): 1467-1476.

- Jahangir SM, Ferdoush J, Parveen K, Ata M, Alam SS, et al. (2016) Evaluation of Knowledge and Attitude of the Future Prescribers About Pharmacovigilance: Experience of Four Medical Colleges of Chittagong. Journal of Chittagong Medical College Teachers' Association 27(1): 4-10.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.