Case Report

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder with Co- Existing Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in A Child, Case Report

*Corresponding author: Al Qassmi Amal, Pediatric Neurology/Epilepsy,section head of neurology, King Saud Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Received: August 05, 2024; Published: August 14, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.23.003115

Abstract

Introduction: Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO) is also known as Devic’s disease, a central nervous system disorder that primarily affects the eye nerves (optic neuritis) and the spinal cord (myelitis), sometimes the brain. On the other hand, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus is a multiorgan and multisystem autoimmune disorder. Its pathophysiology may have protean effects on all components of the CNS. Lupus can present differently and can cause CNS comorbidity, NMO is often mistaken for multiple sclerosis and there are relatively sporadic publications about NMO and overlapping systemic or organ-specific autoimmune diseases, such as Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). In our case 13-year-old, presented as late diagnosis of Lupus with multiple manifestation that complicated with transvers myelitis and optic neuritis as initial presentation, treated with methylprednisolone and immunotherapy with 5 cycle plasmaphereses, with good outcome.

Conclusion: Early diagnosis and treatment may affect the outcome of the disease and reduce the comorbidity. Therefore, it is crucial to develop diagnostic tools for NMO because NMO-IgG is not detectable in all patients.

Keywords: Lupus, Transvers myelitis, Optic neuritis, Child, Skin ulcer

Introduction

Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO) is also known as Devic’s disease, a central nervous system disorder that primarily affects the eye nerves (optic neuritis) and the spinal cord (myelitis), sometimes the brain. It occurs when your body’s immune system reacts against its own cells in the central nervous system. It can occur idiopathically or in conjunction with other systemic diseases [1]. As per Revised consensus criteria published in 2015 base the diagnosis of NMOSD on the presence of core clinical characteristics, AQP4 antibody status, and MRI neuroimaging features. The criteria recognize six core clinical characteristics, which are: Optic neuritis, Acute myelitis, Area postrema syndrome: an episode of otherwise unexplained hiccups or nausea and vomiting, Acute brainstem syndrome, Symptomatic narcolepsy or acute diencephalic clinical syndrome with NMOSD-typical diencephalic MRI lesions and Symptomatic cerebral syndrome with NMOSD-typical brain lesions [2].

It is an uncommon heterogeneous inflammatory demyelinating neuro-immunological disease of the central nervous system on the other hand, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus is a multiorgan and multisystem autoimmune disorder. Its pathophysiology may have protean effects on all components of the CNS. Antibodies are produced against components of the cell nucleus, which lead to a diverse array of clinical manifestations [3]. Our Case report shows the link between SLE &NMO, which can happen during the life span in the middle east, especially in the paediatric group.

Case Report

A 13-year-old Saudi girl presented with a 6-year history of multiple admission due to vague symptoms. Her symptoms started at eight years of age with severe abdominal pain, and fluid collection went to septic shock admitted to PICU after recovering from a rough course she was found to have lower limb weakness. Unfortunately, the mother refused the MRI, and she was discharged home in a wheelchair. As per her mother, she could walk after six months of physiotherapy. She missed multiple appointments. 4 years later, she presented with a painful skin lesion, intermittent fever, and weight loss over six months. Big ulcers over both elbows. Headache and urine retention. She was admitted, investigations were requested, and she underwent upper and lower GI endoscopy for possible inflammatory bowel disease which came normal. Her neurological examination was significant for impaired sensory over upper limbs and power 3/5 with asymmetry reflexes over lower limbs. However, the parent refused an MRI brain and lumbar puncture. Patient was seen by multiple subspecialty (Neurology, Rheumatology, Immunology, infectious and Gastroenterology)

During her admission the following investigations were requested; Immunological work-up was negative: ANA, Rhumatoid factors, DsANA, HIV, Leucocyte marker, MCH, and flow cytometry marker were normal. CBC, Chemistry was normal apart from high ESR>72 and CRP>12. Labs: Urine Culture showed E Coli ESBL Whole exon sequence: Normal (suspected immune deficiency) based on the immunology team.

ID team consulted regarding positive TB interferon-gamma release assay and negative TB PCR, TB AFB, and TB culture; their impression was latent TB and prescribed upon discharge isoniazid and pyridoxine; however, she never received as per mother because they did not find pyridoxine. So, the initial impression was Latent TB, possible immune deficiency (not confirmed). Although no clear explanation of her skin ulcer and previous weakness of lower limb which improved in her second admission and, based on the initial assessment by Rheumatology not typical for autoimmune disease presentation but cannot rule out, consider repeat her blood work up later. A few months later, she presented with a sudden loss of vision. Admitted with a provisional diagnosis of optic neuritis. MRI brain done showed Figure 1.

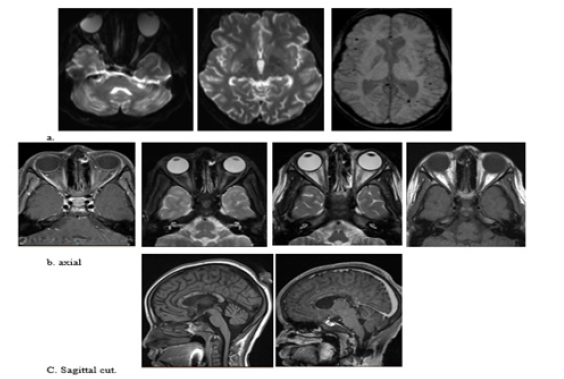

A and c image: Interval resolution seen right basal ganglia and left frontal high FLAIR signal intensity lesions. bilateral cerebral multiple scattered cortical areas of drop of signal at susceptibility weighted images with involvement of the splenium of the corpus callosum and bilateral cerebellar hemispheres denoting micro bleeds.

Figure 1: Mild-to-moderate increased signal intensity of the optic nerves, chiasm and along the optic tracts, associated with increase enhancement of the optic nerves and chiasm indicating bilateral optic neuritis (image). Bilateral Edema of the intraconal fat more on the left side associated with mild increase enhancement along the optic nerve.

Ophthalmology Examination Revealed a Healthy Optic Disc

She received a pulse steroid over three days and IVIG for two days. Finally, she was discharged home with an oral steroid. Her laboratory result was significant for high ESR, reaching 120, High interferon-gamma release assay with TB culture negative, TB PCR, and AFB were negative as well. ID impression was still Latent TB which unlikely to be associated with optic neuritis. Rheumatoid factor negative. SLE serology was negative: Anti-Smith negative, ANA slightly elevated, anti-Ds-DNA negative, c3 c4 normal. IgE 1229 was very high on 1/11/2021. No Spine MRI has been done. No LP done (treated as isolated Optic neuritis).

The latest admission, in March, presented with a decreased level of consciousness and fever. Her symptoms started one week before her presentation with left ear discharge followed by slurred speech and abnormal gait. She was on a tapering dose of steroids. She has a history of joint swelling.

Developmental History: Appropriate to her age, no regression.

Family History: The parent is a first-degree cousin. She has seven siblings. Has younger brother with a history of gangrenous limb followed with auto-amputation of finger and underwent below knee amputation due to complicated septic shock. Her paternal grandmother has a renal failure on dialysis

Upon assessment in ER, her GCS was 6, with hypotension, required intubated then shifted to ICU CSF analysis for the first time revealed: That protein 289 repeated 5. HSV, EBV, and TB PCR came positive along with high ESR and CRP. Started on acyclovir. Repeated CSF study 7 days later came negative for HSV. Neurology was consulted, then recommended MRI cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine with contrast (Figure 2).

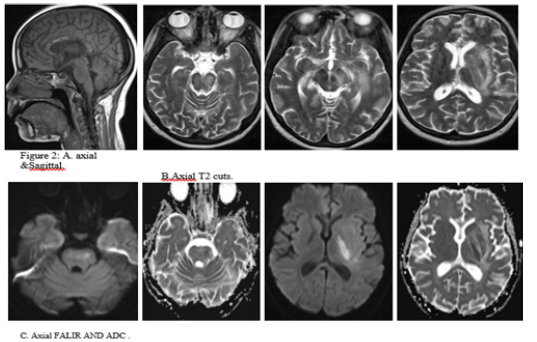

Comparing to the last study dated 30/12/2021 the current study revealed interval developed brainstem, left thalamic, left basal ganglia and left corona radiata area of high T2 and FLAIR(A), signal intensity showing restricted diffusion at DWI and corresponding low ADC(C), values with no enhancement after contrast administration. Interval resolution of previously seen right basal ganglia and left frontal high FLAIR shown in (B,C) signal intensity lesions. No appreciable changes regarding the previously seen corpus callosum and bilateral cerebellar lesions.

Again, seen bilateral cerebral multiple scattered cortical areas of drop of signal at susceptibility weighted images with involvement of the splenium of the corpus callosum and bilateral cerebellar hemispheres denoting micro bleeds. As seen in A and B. No intracranial enhancing abnormalities. The rest of the study shows no significant interval changes (Figure 3).

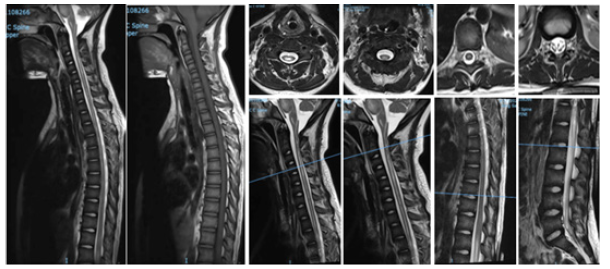

Long segmental area of cervical and dorsal spinal cord intramedullary high signal intensity seen at T2-weightedimages witsh no enhancement after contrast administration starting at the C2-C3 vertebra and ending at T9 vertebra most likely syringomyelia. There is thickening and enhancement of the cauda equina nerve roots. No significant disc bulges or herniations. No suspicious osseous lesions. No paravertebral soft tissue abnormalities.

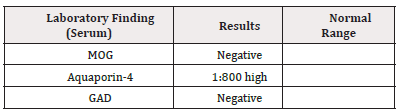

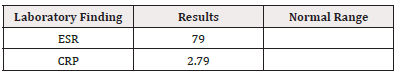

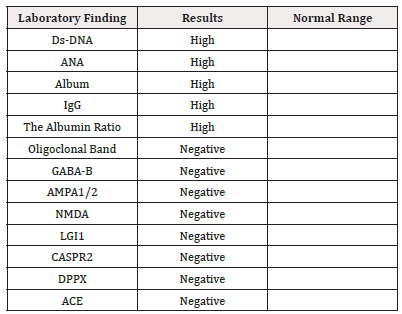

Wide-ranging differential diagnosis encompasses inflammation, infection, demyelinating disorder, autoimmune conditions, and spinal cord tumours. Further laboratory investigation requested summarized in Tables (Tables 1-3).

Based on her clinical presentation, MRI finding, and positive ANA and dsDNA antibodies indicating SLE, in the context of increased white blood cells with lymphocyte predominance on CSF and presence of AQP-4 Antibodies, a diagnosis was made as neuromyelitis Optica.

She has weaned from invasive ventilation to Non-invasive BiPAP alternating with face mask oxygen Connect to cardiopulmonary monitor Alert, obey the command GCS 15/15 She has generalized skin ulcers, with the worst one over her left elbow She is hypo-phonic the right pupil is reactive to light; however, the left eye is conservative to light EOM all intact Bilateral Facial weakness (cannot close her eyelids properly absent nasolabial fold) Gag reflex intact She has flaccid paralysis that improved to 2/5 in both lower limbs (withdrawal flexion from pain) and very weak extension The right upper limb is 0/5, and the left upper is 1/5 with the trivial movement of her fingers Absent reflex in upper and lower limbs Planter Reflex equivocal Challenging to examine her sensory as she is not communicating well; her voice is weak Impression Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) complicated with Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO)

She completed five sessions of plasma exchange followed by Two courses of pulse steroid and one dose of IVIG. Then started on immune modulator mycophenolate mofetil. Received four doses of rituximab two weeks apart. As her laboratory was significant for TB as well, she received Isoniazid and rifampin. She improved within three weeks in terms of the level of consciousness and mild motor improvement. She weaned off from any respiratory support and remained on room air. Physical and occupational therapy evaluated her, and subsequently discharged her to a rehabilitation facility.

Follow up assessment after 1 month from discharge: her clinical exam, alert conscious, oriented, able to set alone, upper limb normal exam with mild decrease power in right side 4/5 and left 5/5, power in lower limb 3/5, normal tone, DTR +1 all over, able to stand with support, make few steps. Vision normal visual field and visual acuity was 25/20 based on neurology assessment. Still on steroid and cyclophosphamide as per rheumatology protocol for lupus.

Discussion

Our patient described above posed a diagnostic challenge because of clinical findings, initial laboratory results, and rapidly deteriorating clinical findings warranting early treatment. NMO spectrum disorder is at the top of the differential diagnosis attributable to her constellation of symptoms, MRI brain and spine findings, and the presence of NMO IgG AQP-4 antibodies. Alternate differential included Systemic lupus erythematosus. The rare neurological manifestation of SLE is Transverse myelitis which rarely can be an initial manifestation of SLE [4]. Optic neuritis is reported in SLE, although in a few cases. SLE and NMO are two different diseases but can exist side by side in one patient. Our patient has dsDNA, along with a history of fever, skin rash, ulcers, and joint swelling but has no classic facial rash, arthritis, proteinuria, pancytopenia, or renal abnormalities. As both serologies for SLE and NMO are positive, she is most likely having concomitant SLE and NMO.

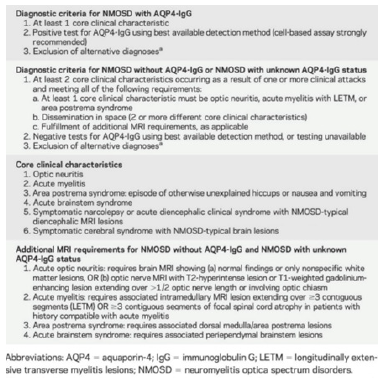

Neuromyelitis Optica is an inflammatory relapsing demyelinating disease of the central nervous system which is rare, primarily affecting both optic nerves and the spinal cord. The pathogenesis of NMOSD depends on Aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibody and complement pathway. At the blood-brain barrier, NMO-IgG selectively binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel in astrocyte foot processes [5] and causes astrocyte injury and injury to the central nervous system through Complement Dependent Cytotoxicity (CDC) and Antibody Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC) [6,7]. As per the International consensus, establishing the diagnosis requires the presence of one core clinical characteristic, as in (Table 3), the presence of NMO IgG antibodies with no other alternative diagnosis [8]. In our case she does have positive aquasporin-4 and 2 core positive, clinical optic neuritis and transvers myelitis’. While in the absence of NMO IgG antibodies, it requires two core clinical criteria, along with the exclusion of alternate diagnosis or the presence of additional MRI findings that will fulfil the criteria. Anti- Aquaporin-4 antibodies are highly specific for the diagnosis of NMO [9]. NMO can be concomitant with autoimmune diseases like Systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, and other autoimmune disorders [10]. Other autoantibodies can be positive in NMO patients’ serology and CSF, for example, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein MOG and myelin basic protein [11].

The risk of optic neuritis and myelitis recurrence in less than one year increases with the presence of antibodies in patients with the first attack of acute myelitis [12]. During an acute attack, the management of choice is methylprednisolone 1 gram/day for 3-5 days. If the patient remained unresponsive to methylprednisolone, should consider plasmapheresis. Today, the first-line therapy with azathioprine or rituximab for severe disease course of NMO calls for prompt initiation of immunosuppressive treatment once the diagnosis of NMO or AQP4-Ab-positive NMOSD has been confirmed. IVIg may be used as the first-line therapy for children or for patients with contraindication to immunosuppressive therapies. In patients with NMOSD who AQP4-Ab are negative, therapy initiation depends on the severity and remission of the first relapse and the clinical course 17.

In the case of side effects or poor response, treatment can be switched from azathioprine to rituximab or vice versa, or to mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, or mitoxantrone 17,9. The third-line therapy for NMO should be applied if disease progression occurs, and if the above treatments fail, the newer agents such as tocilizumab should be given with combination therapy (combination of steroid plus cyclosporin-A or methotrexate or azathioprine; combination of immunosuppression plus intermittent plasma exchange. In our case she did respond to pulse therapy followed by plasmapheresis 5 cycle and other immune therapy for Lupus as per rheumatology guideline, she finished 3 courses of Rituximab after pulse therapy and IVIG and 2 doses of cyclophosphamide, planning to continue for 6 months as per guideline. From neurology point continue oral steroid, continue 3 doses of immune therapy and discharge for rehabilitation and follow up in the clinic.

Although NMO is rarely described in patients with SLE, it can appear as the first manifestation of SLE [13].

It is a well-known phenomenon that these two conditions (NMO and SLE) coincide quite often. The association of SLE and NMO necessitates more research to differentiate between the two conditions [10, 14-16].

Schulz, et al., reported that 2/15 SLE patients studied had ON, and 21–48% of patients with TM had optic nerve involvement [17]. TM may be associated with NMOSD [18]. Many studies have considered the relationship between SLE-TM and NMOSD. Although the results of some studies demonstrate TM is a complication of SLE [19], others have reported that NMOSD and SLE are independent conditions. S Zhang, et al., study found differences in the characteristics of SLE-TM patients who had NMOSD compared to those who did not, such as a lower incidence of SLE typical symptoms (e.g., rash and serositis) and lower rates of hypo-complementize and presence of anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm [20]. NMOSD shares various features with SLE, such as a good response to immunosuppressive therapy. Azathioprine or rituximab have been recommended as first-line therapies for severe NMOSD. Other immunosuppressive agents (including tocilizumab), intermittent plasma exchange, and combination treatment are recommended as second and third-line therapies for NMOSD [21]. However, there is currently no treatment recommendation for SLE-TM patients. Therefore, recommendations for NMOSD treatment could be a reference for SLE-TM patients who meet the NMOSD criteria (Table 4).

IPND Criteria for NMOSD. References: Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. [8] international consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis Optica spectrum disorders. Neurology 85(2): 177-89.

Conclusion

Neuromyelitis Optica is rare disease but can be fatal, earlier testing for NMO-IgG autoantigen-bodies in patients with Optic neuritis is highly recommended, lack of early therapy response we should consider secondary causes especially SLE in patient with ocular manifestation as early presentation. Early diagnosis and treatment may affect the outcome of the disease and reduce the comorbidity.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Jacobi C, Stingele K, Kretz R, Hartmann M, Storch Hagenlocher B, et al. (2006) Neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome) as the first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 15(2):107-109.

- Trebst C, Jarius S, Berthele A, Friedemann Paul, Sven Schippling, et al. (2014) Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS). Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica: recommendations of the neuromyelitis optica Study group (NEMOS). J Neurol 261(1): 1-16.

- Oster JM (2012) The pathophysiology of systemic lupus erythematosus and the nervous system. In: Dr Hani Almoallim ed Systemic Lupus Erythematosus 353-362.

- David Cruz PD, Susana Mellor Pita, Beatriz Joven, Giovanni Sanna, Judith Allanson, et al. (2004) Transverse myelitis as the first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus or lupus-like disease: good functional outcome and relevance of antiphospholipid antibodies. J Rheumatol 31(2): 280-285.

- Lennon VA, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, Verkman AS, Shannon R Hinson (2005) IgG marker of optic-spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel. J Exp Med 202(4): 473-477.

- Graber DJ, Levy M, Kerr D, William F Wade (2008) Neuromyelitis optica pathogenesis and aquaporin 4. J Neuroinflammation 5(1): 22.

- Duan T, Smith AJ, Verkman AS (2019) Complement independent bystander injury in AQP4-IgG seropositive neuromyelitis optica produced by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Acta Neuropathol Commun 7(1): 112.

- Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, Philippe Cabre, William Carroll, et al. (2015) International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology 85(2): 177-189.

- Waters PJ, McKeon A, Leite MI, Rajasekharan S, Lennon VA, et al. (2012) Serologic diagnosis of NMO: a multicenter comparison of aquaporin-4-IgG assays. Neurology 78(9): 665-671.

- Pittock SJ, Lennon VA, De Seze J, Patrick Vermersch, Henry A Homburger, et al. (2008) Neuromyelitis optica and non–organ-specific autoimmunity. Arch Neurol 65(1): 78-83.

- Haase CG, Schmidt S (2001) Detection of brain-specific autoantibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, S100β and myelin basic protein in patients with Devic s neuromyelitis optica. Neurosci Lett 307(2): 131-133.

- Weinshenker BG, Wingerchuk DM, Vukusic S, Linda Linbo, Sean J Pittock, et al. (2006) Neuromyelitis optica IgG predicts relapse after longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Ann Neurol 59(3): 566-569.

- Mehta LR, Samuelsson MK, Kleiner AK, Andrew D Goodman, Jennifer H Anolik, et al. (2008) Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome. Mult Scler 14: 425-427.

- Jarius S, Jacobi C, De Seze J, Helene Zephir, Friedemann Paul, et al. (2011) Frequency and syndrome specificity of anti- bodies to aquaporin4 in neurological patients with rheumatic disorders. Mult Scler 17: 1067-1073.

- Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG (2012) The emerging relationship between neu- romyelitis optica and systemic rheumatologic autoimmune disease. Mult Scler 18(1): 5-10.

- Wandinger KP, Stangel M, Witte T, Patrick Venables, Peter Charles, et al. (2010) Autoantibodies against aquaporin-4 in patients with neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus and primary Sjögrens syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 62(4): 1198-200.

- Schulz SW, Shenin M, Mehta A, Kebede A, Fluerant M, et al. (2012) Initial presentation of acute transverse myelitis in systemic lupus erythematosus: demographics, diagnosis, management and comparison to idiopathic cases. Rheumatol Int 32(9): 2623-2627.

- Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG (2006) Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 66(10): 1485-1489.

- Birnbaum J, Petri M, Thompson R, Izbudak I, Kerr D (2009) Distinct subtypes of myelitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 60(11): 3378-3387.

- Zhang S, Wang Z, Zhao J, Wu DI, Li J, et al. (2020) Clinical features of transverse myelitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 29(4): 389-397.

- Chao Zhang, Meini Zhang, Wei Qiu, Hongshan Ma, Xinghu Zhang, et al. (2020) Safety, and efficacy of tocilizumab versus azathioprine in highly relapsing neuromyelitis Optica spectrum disorder (TANGO):an open-label, multicentre, randomized, phase 2 trail. Lancet Neurol 19(5): 391-401.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.