Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Eating Healthy (“The No White Diet”)

*Corresponding author: Leonard Sonnenschein, The Sonnenschein Institute, 6617 NW 24th Ave. Boca Raton, Florida 33496 USA.

Received: October 13, 2024; Published: October 29, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.24.003222

Abstract

The “No White Diet” is a dietary regimen that focuses on limiting or avoiding certain white-colored foods, typically viewed as processed or high in refined carbohydrates and sugars. This review aims to explore the key principles and food guidelines of the “No White Diet,” emphasizing the importance of consuming nutrient-dense, whole foods for improved health and well-being. The core principle of the “No White Diet” revolves around the exclusion of white-colored foods that are often linked to empty calories and poor nutritional value. This includes sugar, wheat products, white rice, white potatoes, and white flour. By eliminating these items, individuals can transition towards a low-carb, nutrient-rich diet that promotes overall health and weight management. In addition to avoiding the aforementioned white foods, the diet may also recommend reducing sodium intake by limiting regular table salt, as well as restricting high-saturated fat, sugar, cow dairy products like whole milk and full-fat cheeses. Processed foods such as white crackers, chips, and sugary cereals, which offer little nutritional benefit, are also typically excluded from the “No White Diet.” Conversely, the “No White Diet” encourages the consumption of a variety of colorful fruits and vegetables, whole grains like brown rice and quinoa, lean proteins such as chicken, fish, legumes, and some tofu, as well as healthy fats from sources like avocado, olive oil, nuts, and seeds. Dairy alternatives like goat milk are preferred over cow milk, cheese, and butter to reduce potential allergens. By opting for whole, non-GMO/organic, and hypo-allergenic foods, individuals following the “No White Diet” aim to improve their nutritional intake, support weight loss efforts, enhance energy levels, and reduce the risk of chronic diseases associated with poor dietary choices. Fresh herbs, spices, and seasonings are recommended for flavoring dishes without relying on added sugars and salt, contributing to a more balanced and satisfying eating experience. The “No White Diet” offers a structured approach to eating healthily by prioritizing nutrient-dense foods and minimizing intake of processed, empty-calorie items. By following the guidelines outlined in this review article including “the no white diet” and making thoughtful food choices, individuals can work towards improving their overall health, achieving weight management goals, and enhancing their well-being through a diet rich in essential nutrients and whole food sources.

Keywords: Eating healthy, Eating local, Food supplements, Fruit choices, Healthy food oils, Hypoglycemic, Hypoallergenic, “No White Diet”, Keto diet, Low calorie diet, Vegan choices, No cow milk, Goat milk, Sheep cheese, 2000 Calorie diet, Starch and Vegetable choices, Intermittent fasting, Carnivore diet

Acronyms: ALA-Alpha-Linolenic Acid; CSA-Community-Supported Agriculture; DHA-Docosahexaenoic Acid; EPA-Eicosapentaenoic acid; LCKDLow- Carbohydrate Ketogenic Diets; MCTs-Medium-Chain Triglycerides; OMAD- One-meal-a-day; VLCKD- Very Low-Carbohydrate Ketogenic Diet

Introduction

Poor diet has been attributed to various types of malnutrition [1] as well as the primary risk factor for disability and even death globally [2]. The high global prevalence to poor nutritional status is due to unhealthy food environments and poor food systems. According to High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition [3], factors that can be physical, political, economic and socio-cultural environments in which people live usually influence individual food choices. These factors are collectively forming the food environment that reflects context in which people acquire, prepare and consume food [4]. Local food environments can be grouped into the community, consumer and organizational nutrition environments [5]. As pointed out by Glanz, et al. [5], the community nutrition environment refers to number, type, location and accessibility to food stores in a community while the consumer nutrition environment refers to the availability of healthy food choices, price, promotion, quality and placement of food items. Retail food environment is composed of the community and consumer nutrition environments combined [6]. The retail food environment can therefore be described as accessibility to local food stores and markets, and the availability and affordability of healthy foods in these stores and markets [5].

To understand the dimensions of food access or food environment, you should consider availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability and accommodation [6]. Contextually in the food environment, availability is defined as the density or presence of different types of food stores within a specified area. Accessibility can be the geographic location of the food stores which is usually defined by the proximity or the diversity or variety of different types of food stores. When looking at food affordability, this is the purchasing power and food prices measured by store audits and price indices [7]. Acceptability looks at people’s attitude on the attributes of their local food environment, it is measured as people’s perception on quality of foods sold or as store audit food quality score [6]. As reported by Caspi, et al. [6], accommodation refers to how well the local retail food environment caters to residents’ needs for instance store operating hours and types of payment option offered to customers. Yamaguchi, et al. [8] reported that perceptions on availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability and accommodation in the local retail food environment can be measured. Food choice is a process by which people consider, acquire, prepare, store, distribute, and consume foods and beverages as pointed out by Sobal, et al. [9] and it’s determined by individual and social factors, as well as physical and macro-level environment [10]. Turner, et al. [11] indicated that changes in the food environment due to changes in the food supply and demand usually affect individuals’ food choices and hence affect diet quality and dietary habits. Story and colleagues reported that healthy retail food environments have been shown to be characterized by access to food stores such as supermarkets, grocery stores and farmers markets, and limited presence of Fast-Food restaurants in a community, and the availability of healthy affordable food products within stores [12]. A greater dietary diversity can be achieved in a healthy food environment with improved access to fruits and vegetables [13] leading provision of healthier options of pre-packaged foods, prepared and readymade meals in different types of retail food stores [14]. Relationship of the local food environment with dietary outcomes and nutritional status have been reported widely [6,15-19]. The effects of use of inorganic input effects on downstream has been noted and thus the advocacy for use of food produced organically. In this review article, procedures are provided to guide thoughtful food choices that an individual can pursue as they work towards improving their overall health, achieving weight management goals, and enhancing their well-being through a diet rich in essential nutrients and whole food sources.

What is “The No White Diet”

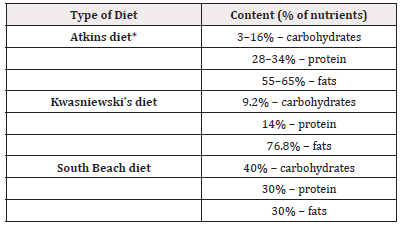

The “No White Diet” is a dietary approach that involves limiting or avoiding certain white-colored foods that are often considered processed or high in refined carbohydrates and sugars in order to move towards low carbs, also with attention on non-GMO/organic and hypo-allergenic. While the specific rules can vary depending on the source, the general principle of the “No White Diet” is to promote whole, nutrient-dense foods and minimize consumption of processed, empty-calorie foods. While on the program it is essential to refrain from eating sugar, wheat and wheat products such as pasta/couscous, no white rice, white potatoes, or white flour [20]. Some versions of the diet may recommend reducing sodium intake by avoiding regular table salt. Some dairy products, especially those high in saturated fat and sugar, may be limited and includes whole milk and full-fat cheeses. Foods like white crackers, chips, and sugary cereals that are highly processed and lacking in nutrients [21]. Foods included on a “No White” Diet include emphasizing a variety of colorful fruits and vegetables rich in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. Choosing whole grains like brown rice, quinoa, oats, and whole wheat bread over refined white grains. Including sources of lean protein like chicken, fish, legumes, and tofu. Milk substitutes and goat milk should be considered. Refrain from cow milk, cheese and butter. Using fresh herbs, spices, and seasonings to add flavor without relying on added sugars and salt. Incorporating sources of healthy fats like avocado, olive oil, nuts, and seeds [22]. Healthy oils [23] are essential components of a balanced diet, providing valuable nutrients like essential fatty acids and vitamin E and choices available to users are shown in Table 1.

It’s important to note that while the “No White Diet” can help individuals reduce their intake of processed foods and empty calories, it’s essential to ensure that the diet remains balanced and provides all necessary nutrients for overall health [32].

Healthy Food Choices

Making healthy food choices is essential for maintaining overall health and well-being. Include a wide variety of foods from all food groups to ensure you’re getting a range of nutrients. This includes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats. Aim to fill half your plate with colorful fruits and vegetables, as they are rich in vitamins, minerals, fiber, and antioxidants that are essential for good health. Choose whole grains such as brown rice, quinoa, whole wheat bread, oatmeal, and whole grain pasta over refined grains to increase fiber intake and support better digestion. Opt for lean sources of protein like poultry, fish, legumes, some tofu, and nuts. Protein is essential for muscle repair, energy, and satiety. Include sources of healthy fats like avocado, olive oil, nuts, seeds, and fatty fish (such as salmon or mackerel) to support heart health and brain function. Choose low-fat or non-fat dairy options like skim milk, and reduced-fat cheeses to meet your calcium and protein needs while minimizing saturated fat intake. Reduce intake of foods and beverages high in added sugars, such as sugary drinks, sweets, and processed snacks. Opt for naturally sweet options like fruits for a healthier alternative. Be mindful of portion sizes to avoid overeating, especially with calorie-dense foods. Use smaller plates, read labels, and listen to your body’s hunger and fullness cues. Drink plenty of water throughout the day and limit sugary drinks and excessive caffeine intake. Water is essential for overall hydration and bodily functions. Opt for healthier cooking methods like grilling, baking, steaming, or sautéing with minimal oil instead of deep-frying. This helps retain nutrients in food and reduces added fats [33]. Remember, a healthy diet is not about strict rules or deprivation but about making informed choices that support your health goals. Balance, moderation, and consistency are key components of a sustainable and nourishing eating pattern [34].

No Cow Milk

Cow’s milk and cow’s milk products such as yogurts, cheeses, etc. should be avoided. Sheep and goat’s milk products are allowed. Goat milk can be a healthy choice for some individuals, depending on their dietary preferences, nutritional needs, and health considerations. There is health benefits associated with use of goat milk. Goat milk is rich in essential nutrients such as protein, calcium, phosphorus, and vitamins like vitamin A and vitamin D [35-40]. It contains slightly lower levels of lactose compared to cow’s milk, making it potentially easier to digest for some people with lactose intolerance. The fat globules in goat milk are smaller than those in cow’s milk, which some individuals find easier to digest. Goat milk contains all nine essential amino acids, making it a complete protein source that supports muscle maintenance and overall health. Goat milk is a good source of minerals like calcium and phosphorus, which are essential for bone health and various bodily functions [35-37]. Goat milk naturally contains vitamin A, which is important for vision and immune function. Some brands may also be fortified with vitamin D for bone health. Individuals who are allergic to cow’s milk or have lactose intolerance may find that they can tolerate goat milk better due to differences in protein and lactose content. It’s important to note that while goat milk may be easier to digest for some. Some people prefer the taste of goat milk, which is slightly tangy and distinct from cow’s milk. It can be a great option for adding variety to your diet. Goat milk is available in various forms, such as whole, reduced-fat, and lactose-free options, making it versatile for drinking, cooking, and baking [41].

Sheep Cheese

Comparing sheep cheese to cow milk cheese in terms of health benefits is complex and depends on various factors. Sheep cheese is known for its rich and distinct flavor. It tends to have higher levels of protein, calcium, and certain vitamins compared to cow milk cheese. Sheep cheese typically contains higher levels of fat, including more healthy fats like omega-3 fatty acids. However, this can also result in higher calorie content. Sheep cheese may contain lower levels of lactose compared to cow milk cheese, making it easier to digest for some individuals with lactose intolerance. Sheep cheese is known for its excellent amino acid profile, but cow milk cheese also provides essential amino acids. Sheep cheese is known to be rich in minerals like calcium and zinc [35,36,42,43].

2000 Calorie Diet and Eating in Moderation

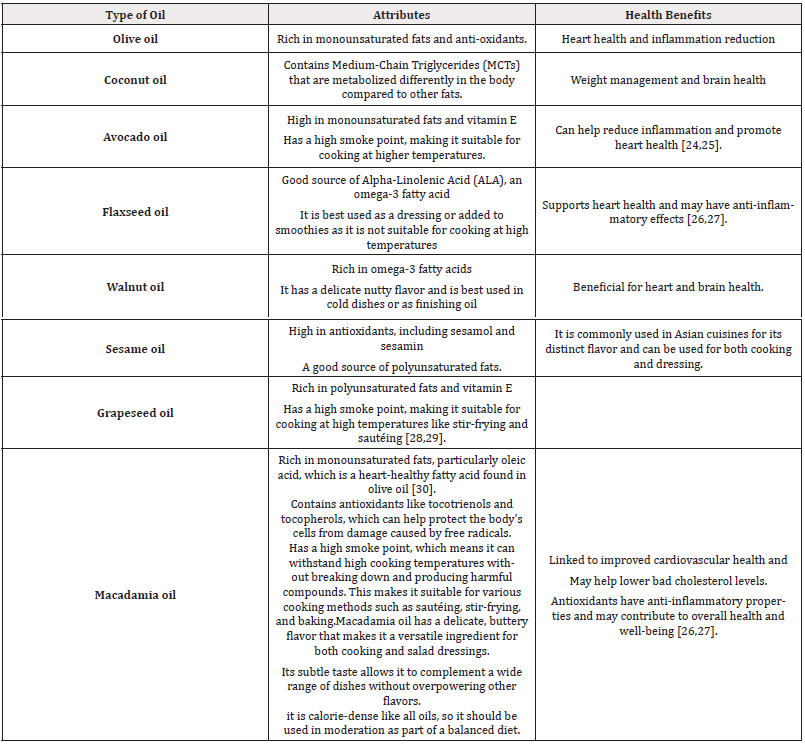

A 2000 calorie diet is a general benchmark used for nutritional guidance. It represents the average daily caloric intake recommended for adults to maintain their weight, although individual needs may vary based on factors like age, gender, weight, activity level, and overall health. Aim to distribute your calories from different macronutrients - carbohydrates, proteins, and fats - in a balanced way. As a general guideline, this could include around 10-35% of total calories from protein, 20-35% from fats while carbohydrates ranges are given in Table 2. Focus on nutrient-dense foods that provide essential vitamins, minerals, and other key nutrients within your calorie limit. Include a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats in your meals. Be mindful of portion sizes to avoid overeating, especially calorie-dense foods like oils, nuts, and processed snacks. Using measuring cups, a food scale, or visual cues can help with portion control. Plan your meals and snacks in advance to ensure they align with your calorie goals and contain a good balance of nutrients. This can help prevent impulsive food choices and support a more nutritious diet. Regular exercise is important for overall health and can help you manage your weight. Combining a 2000 calorie diet with appropriate physical activity can support better health outcomes (at least 20 minutes of vigorous exercise per day). Remember to drink plenty of water throughout the day to stay hydrated and support your body’s functions. Sometimes thirst can be mistaken for hunger, so staying hydrated may also help manage appetite. If you have specific dietary concerns, health conditions, or weight management goals, consider consulting a healthcare provider or a registered dietitian to develop a personalized nutrition plan tailored to your needs [34].

Table 2: Amount of Carbohydrate (g/day) in different types of diet [53].

Note*: VLCKD: Very Low-Carbohydrate Ketogenic Diet.

Incorporating lean meats and fatty fish into your diet can be a great way to obtain essential nutrients like protein, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals. Lean meats include skinless chicken breast, which is a great source of lean protein, low in fat, and versatile for various recipes. Turkey is another lean protein option that can be used in place of higher-fat meats like beef. For lean beef, opt for cuts like sirloin, tenderloin, or round cuts that are lower in saturated fats. For lamb, opt for lean cuts of lamb like loin, shank, or leg, and trim visible fat before cooking to reduce overall fat content. In moderation and as part of a balanced diet, lean cuts of lamb can provide valuable nutrients and contribute to a healthy eating plan. As with any food, the key is to enjoy lamb in moderation, choose lean cuts, practice portion control, and balance your overall diet with a variety of nutrient-dense foods. Venison and bison are the lean red meat options with a rich flavor and lower fat content compared to beef [32]. For fatty fish; salmon is rich in heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids; salmon is a popular choice for its flavor and nutritional benefit. Mackerel is another oily fish high in omega-3s, also a good source of vitamin D. Sardines is a small fish with big nutritional benefits that is packed with omega-3s and calcium. Trout is a flavorful fish that is high in protein and omega-3 fatty acids. Herring is a nutrient-dense fish that is particularly high in omega-3s and vitamin D [44].

When choosing meat and fish, select for whole cuts of meat and fish over processed options like sausages or deli meats, which may contain added sodium and preservatives. Choose healthier cooking methods like grilling, baking, or broiling to minimize added fats and oils. Control portions, be mindful of portion sizes to moderate calorie intake and ensure a balanced diet. Variety is key, rotate between different types of meats and fish to ensure a diverse nutrient intake. By incorporating a variety of lean meats and fatty fish into your diet, you can enjoy delicious meals while reaping the nutritional benefits they offer [34].

Eating Keto

Low-Carbohydrate Ketogenic Diets (LCKD)

In an open letter to the public published in 1869, William Banting in the fourth edition of his paper entitled “Letter on Corpulence, addressed to the Public,” reported that a low-carbohydrate diet is very effective in reducing body weight [45]. According to Paoli [46] LCKD have been used in the treatment of diabetes and pediatric epilepsy before its use for obesity. Recently, further studies have indicated benefits associated with LCKD to include the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders [47], infantile spasms, bipolar illness [48,49], Alzheimer’s disease, and brain tumor [50]. According to Chester, et al. [51] and Krebs [52], a high-fat diet changes the body’s metabolism to a new direction. Fatty acids usually undergo oxidation in the liver to form ketone bodies. When ketone bodies are formed in excess of the body’s ability to metabolize, they are usually accumulating in the body resulting in ketosis which is caused by high fat diet referred to as ketogenic diet. For effective comparison of the ketogenic diets in various studies, definitions of low-carbohydrates diets in different forms were suggested by Feinman, et al. [53] as shown in Table 2.

Table 3 presents percentage of nutrient content of different types of diet including Atkins diet [54], Kwasniewski’s, Zone [55], and the South Beach Diet [56].

Table 3: Percentage of nutrient content in different types of diet [54-56].

Note*: *Percentage range depends on individual status.

A ketogenic (keto) diet is a high-fat, moderate-protein, and very low-carbohydrate eating plan designed to shift the body’s metabolism away from using carbohydrates as the primary source of energy towards utilizing fats for fuel [57]. A ketogenic diet consists of high-fat foods such as the avocados, nuts and seeds (almonds, walnuts, chia seeds), olive oil, coconut oil, and avocado oil, goat butter and ghee, fatty fish (salmon, mackerel) and high-fat meats. The protein intake is moderate in a keto diet to support muscle maintenance and other body functions. Good sources of protein include poultry (chicken, turkey), beef and lamb, fish and seafood, eggs, tofu and tempeh (low use). Carbohydrate intake is drastically reduced in a keto diet to induce a state of ketosis, where the body starts using ketones derived from fats as its primary fuel source. Carbohydrate sources are typically limited to non-starchy vegetables (leafy greens, broccoli, and cauliflower). Berries (in limited amounts), some nuts and seeds. Foods high in sugar and grains are generally avoided on a keto diet due to their high carbohydrate content. This includes no sugar, no grains and no starchy vegetables [58]. Since the keto diet can have diuretic effects, it’s crucial to stay hydrated and ensure an adequate intake of electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and magnesium. Some variations of the keto diet involve cycling periods of higher carbohydrate intake, known as cyclical ketogenic diet or targeted ketogenic diet, to support athletic performance or metabolic flexibility [59]. It’s important to note that following a keto diet requires careful planning to ensure adequate nutrient intake and to minimize potential side effects such as the “keto flu.”

Side Effects of Ketogenic Diet

According to Dashti, et al. [60], there is usually a feeling of lethargy, fatigue, and headache during the shift from carbohydrate to fat based energy utilization or the keto-adaptation [61]. Due to efficacy of LCKD, hypoglycaemia may occur in diabetic patients [62] which may result in significant reduction in the units of insulin required to be administered or cessation or reduction in the doses of oral drugs administered for type 2 diabetes [63,64]. According to Ballaban, et al. [65], dehydration, hypovitaminosis and dyselectrolytemia as the negative events associated with ketogenic diet. To address the side effects, daily supplements of electrolytes, multivitamins, potassium citrate and calcium, vitamin D, and minerals should be given during the period of ketogenic diet administration [66]. A study published by Hartman & Vining [67] in 2007, the formation of kidney stones and increased production and the decreased excretion of uric acid as another side effect of LCKD. This is attributed to the limited intake of fluid leading to the suppression of thirst by ketone bodies. Ketone bodies are reported to be involved in the suppression of food intake. Subjects of ketogenic diet have a reduction in the intake of healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables which contain polyphenols and antioxidants that fight against the free radicals. Milder, et al. [68] reported that type 2 diabetes is associated with oxidative stress and limiting the supply of polyphenols and antioxidants may increase the imbalance of antioxidant-oxidation system in our body. In order to overcome this situation, it is suggested to supplement the ketogenic diet with extracts of polyphenols and antioxidants, especially in patients with type 2 diabetes. According to Volek, et al. [69], constipation is also a noted as a side effect of LCKD, possibly be due to the decreased fiber content and dehydration due to the suppression of thirst by ketones. Such situation can be prevented by increasing the fiber content in the diet, increasing fluid intake and using laxatives [70].

Intermittent Fasting

As reported by Alnasser & Almutairi [71], fasting practices have been part of human life for religious, cultural, or health reasons for thousands of years. For Muslims, the culturally intrinsic practice of fasting has been around for centuries. The Muslim community worldwide, including Muslims in Saudi Arabia, fasts for an entire lunar month during Ramadan. It is important to note that intermittent fasting is different from fasting. Traditional fasting is refraining from consuming calories for an extended period. There are several ways to fast ranging from drinking only water to other modified approaches that may include some calories. Fasting duration varies and may be up to 28 days or more. Intermittent fasting has been practiced for millennia [72] and in the preliterate society, intermittent fasting was the norm when food was scarce. Fasting is characterized by longer intervals between meals without enduring nutritional deficiency [73]. According to Longo & Mattson [74], fasting is a dietary pattern which encompass cycles of fasting for a duration varying from 12- 24 hours alternating with periods of normal food intake. It is not related to a particular type of diet but a pattern of eating. There exist different regimens of intermittent fasting being practiced and the common pattern included 12-16 hours of daily fasting, 20-24 hours of fasting 2 days a week or more intense patterns, such as alternate-day fasting [75,76]. There are several methods for intermittent fasting. The most common approach to intermittent fasting includes the 16:8 method, involves fasting for 16 hours and eating all meals within an eight-hour window each day. Eat-stop-eat method consists of fasting for 24 hours once or twice a week. 5:2 intermittent fasting approach involves following a regular diet five days a week and significantly reducing caloric in take on the other two days. Alternate-day fasting method includes alternating between days of regular eating and fasting. One-meal-a-day (OMAD), with this method, you fast for 20 hours daily and eat one large meal, typically at night.

Biology of Intermittent Fasting

The primary source of energy for humans is glucose. The metabolism of glucose is time dependent such that it is a function of time since the last meal. For humans, the blood glucose level falls shortly after consumption of a carbohydrate meal [77]. Depending on the amount of glycogen stored in the liver and the energy expenditure after that, the glycogen level will be diminished and fat metabolism becomes the energy source, through the production of ketone bodies during the 12-36 hours after carbohydrate intake [76,78]. The brains among several organs, can use ketone bodies of energy requirements. This kind of metabolic switch, from glucose to ketone bodies, is the key characteristics metabolic feature of fasting [72,74]. According to Browning, et al. [79], ketone bodies naturally produced during fasting are minimally increased in the first 24 hours after the last meal. It has been reported that the key mechanism of benefits of fasting is through heightened insulin sensitivity which is decreased in type 2 diabetes mellitus [80-85]. Insulin resistance has been attributed to be promoting atherosclerosis and subsequent vascular diseases. Fasting is also associated with reduction in lipid and blood pressure levels in controlled clinical trials in human [86]. Intermittent fasting in principle promotes vascular health. As reported by Merimee & Fineberg [87], Fasting has been associated with optimization of cellular metabolism which is evident in alterations in thyroid hormones and amount of free oxygen radicals that are produced as the byproducts of normal oxidative. Free radicals have the potential in causing genome mutations and diseases. During fasting, metabolism and protein synthesis are temporary reduced and free radicals’ formation is decreased [88]. Cells are further reported to undergo stress response and adaptation during fasting. The changes include DNA repair, removal of cellular waste, enhanced antioxidant mechanisms or autophagy [88]. When feeding is restored and glucose supply, cells usually regain homeostasis and become more stress resistant. In a report published in 2018 by Mattson & Arumugam [88], brain cells in animals maintained on intermittent fasting exhibited improved function and adaptive response metabolic, traumatic, and oxidative stress.

Vegetables and Starches

When choosing hypoallergenic foods consider that many people show signs of allergic reactions to these foods [89]; almonds, soy, eggplant, citrus-oranges (allergies to the fruit and or to the coloring, pesticides, and or other agricultural inputs) and tomatoes, some (sprouted)/whole grains, oats, (sprouted)/beans and whey. In the food allergy prevention space, greater focus has been placed on the early introduction of the complementary diet in infancy which is in contrast to the previous approach of prolonged food allergen avoidance which, in hindsight, may have paradoxically increased the rate of food allergies[90-94].

Incorporating a variety of vegetables (recommended 2 servings daily) and starches into your diet is essential for ensuring a well-rounded and nutritious eating plan. Dark leafy greens such as spinach, kale, swiss chard, and collard greens are rich in vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients while being low in calories. Cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, and cabbage are packed with fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants that support overall health. Colorful vegetables such as bell peppers, tomatoes, carrots, sweet potatoes, and beets provide a range of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, each with unique health benefits. Legumes including beans, lentils, chickpeas, and peas are excellent sources of plant-based protein, fiber, and essential nutrients like iron and folate. Root vegetables such as potatoes (limit to 2 small potatoes with skin, preferably boiled), sweet potatoes, carrots, and parsnips are rich in fiber, vitamins, and minerals, providing sustained energy and promoting digestive health[95].

For starches; whole grains such as quinoa, brown rice, whole wheat, barley, and oats are nutritious sources of complex carbohydrates, fiber, and essential nutrients like B vitamins and iron. Sweet potatoes is a nutrient-dense tubers that are a great source of complex carbohydrates, fiber, and vitamins like A and C. The legumes, in addition to being a good source of plant-based protein, legumes like beans and lentils also provide a healthy dose of complex carbohydrates and fiber. Despite being high in starch, corn is also a good source of fiber and antioxidants when consumed in its whole form. Opt for products made from whole grains for added fiber, vitamins, and minerals compared to refined grains [22]. By incorporating an array of vegetables and starches into your meals, you can create nutritious and flavorful dishes that provide essential nutrients, fiber, and energy for overall health and well-being.

Vegan Choices

A well-planned vegan diet can provide all the nutrients your body needs while offering numerous health benefits. The plant-based protein sources including legumes (limit if allergic) such as beans, lentils, and chickpeas. Reduce soy products including tofu. For nuts and seeds include almonds, walnuts, chia seeds, hemp seeds, and flaxseeds are rich in protein, healthy fats, and minerals like iron and zinc. For whole grains include quinoa, brown rice, bulgur, farro, and whole wheat provides protein and essential amino acids to support muscle function and overall health [95].

For vitamin and mineral-rich foods; dark leafy greens such as spinach, kale, swiss chard, and collard greens are packed with vitamins A, C, K, and minerals like calcium and iron. Colorful vegetables such bell peppers, carrots, sweet potatoes, and tomatoes provide a variety of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants for overall health. Seaweed and algae such as spirulina, nori, and seaweed are rich in iodine, iron, and other minerals that may be lacking in a vegan diet [22].

The healthy fats such as avocados are rich in healthy monounsaturated fats; avocados also provide fiber, vitamins, and minerals for heart health and overall well-being. Nuts and seeds such as walnuts, almonds, chia seeds, and flaxseeds are sources of omega-3 fatty acids, beneficial for brain health and inflammation control [96].

For the fortified foods and supplements, since vitamin B12 is primarily found in animal products, vegans may need to supplement or consume fortified foods like nutritional yeast, plant-based milks, or cereals. Calcium and vitamin D help to support bone health, consider fortified plant milks, leafy greens, and supplements if needed. For the omega-3s you should consider algae-based supplements for Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) omega-3 fatty acids, important for heart health and brain function[97].

Carnivore (All-Meat) Diet

The carnivore diet is made up of meat, fish, and other animal foods like eggs and certain dairy products, It excludes all other foods, including fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains, nuts, and seeds. It has been claimed to support with weight loss plans, mood issues, and blood sugar regulation. The diet has been found to be extremely restrictive since it eliminates all foods except meat and animal products making it low in vitamin c, folate, has no fiber, and might be difficult to maintain. The carnivore diet stems from the controversial belief that human ancestral populations ate mostly meat and fish and that high-carb diets are to blame for today’s high rates of chronic disease [98]. The foods to eat include meat such as beef, chicken, turkey, lamb, etc. Organ meats like liver, kidney, heart, brain; fish includes salmon, mackerel, sardines, tilapia, herring, etc. Other animal products such as eggs, bone marrow, bone broth, etc. [99].

Eating Local

Eating locally grown food can offer a multitude of benefits for both individuals and the community as a whole. The advantages of consuming locally sourced food include the environmental benefits such as reduced carbon footprint; preservation of farmland; and biodiversity conservation. The economic benefits include supporting local economy; job creation; and food security. The health benefits include access to freshness and nutrient content; local produce is often fresher (less spoilage) since it doesn’t have to travel long distances, leading to higher nutrient content and better taste. Eating locally encourages consuming foods that are in season, promoting a diverse and well-rounded diet throughout the year and shorter supply chains can lead to less food waste since locally grown produce is less likely to spoil during transport or storage. The community benefits include connection to food sources whereby buying local fosters a closer connection between consumers and their food sources, promoting understanding and appreciation for where food comes from. Farmers’ markets and local food events provide opportunities for community engagement, social interactions, and cultural exchange. Local food systems often prioritize transparency and accountability, allowing consumers to inquire about farming practices, food handling, and product origins. By choosing to eat locally sourced foods, you can not only enjoy fresher and more nutritious produce but also contribute to a more sustainable and resilient food system while supporting your local community and economy. Consider exploring farmers’ markets, farm-to-table restaurants, and community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs to experience the benefits of eating local firsthand [100].

Fruits

When selecting fruits (recommended 2 servings daily) for your diet, it’s essential to prioritize variety to benefit from a wide range of nutrients. The best fruit choices that can offer a diverse array of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and fiber should be considered. The berries such as blueberries are rich in antioxidants, particularly anthocyanins, which have been linked to various health benefits, including improved brain function and reduced oxidative stress; strawberries are a good source of vitamin C, manganese, folate, and potassium, with potential benefits for heart health, blood sugar regulation, and cancer prevention; raspberries are high in fiber and antioxidants, such as ellagic acid, which may help protect against chronic diseases like cancer and heart disease [101].

The citrus fruits such as oranges are packed with vitamin C, fiber, and other nutrients that can support immune function, skin health, and heart health. Grapefruits are low in calories and high in fiber and vitamin C, with potential benefits for weight management, heart health, and blood sugar control. Lemon is a good source of vitamin C and plant compounds with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which can support digestive health and immunity [102].

The tropical fruits such as pineapple that is rich in vitamin C, manganese, and bromelain, an enzyme with anti-inflammatory and digestive benefits. Mango is high in vitamins A and C, as well as fiber and antioxidants, promoting eye health, immune function, and skin health. Papaya contains vitamins A and C, folate, and digestive enzymes like papain, which may support digestion and reduce inflammation [103].

The stone fruits include peaches which is a good source of vitamins A and C, as well as fiber and antioxidants that can benefit skin health, digestion, and immunity. Plums are rich in vitamins K and C, fiber, and antioxidants, which may promote bone health, heart health, and digestion. Cherries are packed with antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds; cherries may help reduce exercise-induced muscle soreness and promote sleep quality.

The apples are high in fiber, vitamin C, and antioxidants, apples have been associated with improved heart health, weight management, and digestion. A pear is a good source of fiber, copper, and vitamins C and K, pears can support gut health, blood clotting, and immune function. Including a variety of fruits in your diet can provide numerous health benefits, so aim to incorporate different colors and types of fruits to ensure you’re getting a broad spectrum of nutrients to support overall well-being. Remember to choose fresh, whole fruits whenever possible and consider including them in meals, snacks, smoothies, or as healthy dessert options [104].

Supplements

In an ideal scenario, obtaining nutrients through a balanced diet rich in whole foods are the best approach for overall health and well-being. However, in some cases, supplements can be beneficial to fill specific nutritional gaps or address certain health concerns. Supplements can complement a healthy diet. The multivitamin and mineral supplements ensure you’re meeting your daily requirements for essential vitamins and minerals. Omega-3 Fatty Acids (fish oil or algal oil) supports heart health, brain function, and reduce inflammation. Vitamin D supports bone health, immune function, and mood regulation [105,106]. Prebiotics promote gut health, digestion, and immunity by supporting beneficial gut bacteria. Calcium and magnesium support bone health, muscle function, and nerve transmission. Consider a supplement that provides both calcium and magnesium in the appropriate ratio for better absorption. Iron prevents or addresses iron deficiency, particularly important for pregnant women, menstruating individuals, and vegetarians/ vegans. Vitamin B12 is essential for nerve function, DNA synthesis, and red blood cell production, especially important for vegans and older adults [107,108]. Choose a supplement with methylcobalamin or cyanocobalamin, as they are well-absorbed forms of vitamin B12. A diet focusing on a diverse, nutrient-rich diet should always be the foundation of a healthy lifestyle [109].

Overdosing on Supplements

Overdosing on dietary supplements can have serious consequences and should be avoided. While vitamins and minerals are essential for good health, taking excessive amounts can lead to adverse effects [110]. Some common symptoms of vitamin or mineral overdose may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, headaches, and in severe cases, organ damage. It is important to follow recommended guidelines for supplement intake as established by health authorities or your healthcare provider. If you suspect you have taken too much of a dietary supplement or are experiencing symptoms of overdose, seek medical help immediately. Providing the medical staff with information about the supplement and the amount you have consumed can help in determining appropriate treatment. Additionally, it is advisable to consult with a healthcare provider before starting any new supplement regimen to ensure it is safe and appropriate for your individual health needs and that there are no contraindications for any supplements or medications being used. Eating a well-balanced diet is generally the best way to obtain the necessary nutrients for optimal health, and supplements should only be used when recommended and monitored by a healthcare professional [111].

Low Glycemic and Restricted Carbohydrates Choices

A low glycemic, restricted carbohydrate diet focuses on consuming foods that do not cause rapid spikes in blood sugar levels. Such a diet includes non-starchy vegetables like leafy greens (spinach, kale, lettuce), broccoli, cauliflower, bell peppers, zucchini, and cucumbers. Lean proteins like skinless chicken, turkey, fish, eggs, tofu, and legumes (like lentils and chickpeas) can be included. Healthy fats such as avocados, nuts (almonds, walnuts), seeds (chia, flaxseeds), and olive oil are usually incorporated. When grains are included, choose those with a lower glycemic index, such as quinoa, barley, and steel-cut oats. The fruits that lower-sugar fruits like berries (strawberries, blueberries, and raspberries), apples, and citrus fruits are preferred over high-sugar options like bananas and tropical fruits. Restricted dairy; goat or sheep milk products or vegan alternatives with low glycemic index i.e. dairy alternatives like unsweetened nut milk. For legumes; beans, lentils, and chickpeas are good sources of fiber and are lower on the glycemic index. The sweeteners; natural stevia and monk fruit can be used as sugar substitutes instead of high-glycemic sweeteners, restrict use of alcohol-based sugars such as ethyritol [112].

Hypoallergenic Choices

A hypoallergenic diet is designed to minimize the risk of triggering allergic reactions or sensitivities to certain foods. It typically involves removing common allergens or substances that commonly cause food sensitivities from your eating plan [113]. A hypoallergenic diet may vary depending on individual sensitivities or allergies, but some general guidelines include the elimination of common allergens such as dairy (cow’s milk, cheese, yogurt), gluten (wheat, barley, rye, and often oats), soy (soybeans and soy products), eggs (both egg whites and yolks), shellfish (shrimp, crab, lobster, etc.) and nuts (peanuts, tree nuts like almonds, walnuts, etc.).

Focus on whole, minimally processed foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables, except for those to which you may be sensitive. Lean protein sources including poultry, fish (if not allergic), and legumes. Whole grains such as quinoa, rice, and gluten-free grains. Fat products including sources like olive oil, avocado, and seeds (if not allergic). Using fresh herbs and spices to flavor meals naturally and encouraging water intake as the primary beverage choice [114].

For a hypoallergenic diet consider a gradual reintroduction after a period of elimination, slowly reintroduce foods one at a time to identify triggers. Keep a food diary documenting what you eat and any symptoms experienced can help pinpoint potential allergens. Working with a registered dietitian or allergist can help tailor the diet to your specific needs and ensure proper nutrient intake. Pay attention to getting all essential nutrients from alternative sources when eliminating certain food groups. Checking food labels for hidden allergens or cross-contamination is essential. Opt for cooking methods like baking, steaming, or sautéing instead of frying to minimize potential allergen exposure. When preparing meals, use separate utensils and kitchen equipment for allergen-free foods. While a hypoallergenic diet can be beneficial for individuals with food allergies or sensitivities, it’s crucial to approach it thoughtfully to ensure it meets your nutritional needs. Always consult with a healthcare provider or a registered dietitian before making significant dietary changes, especially if you suspect you have food allergies or intolerances, to receive appropriate guidance and support [115].

Alcohol

When incorporating alcohol into your diet plan, it’s important to make informed choices to balance enjoyment with maintaining your overall health and wellness goals. Moderation is key; limit alcohol intake to moderate amounts, which is generally defined as up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men. Be mindful of the additional calories in alcoholic beverages, as they can contribute to weight gain if consumed excessively. Opt for lower-calorie choices like light beer, wine spritzers, or dry wines to reduce overall caloric intake. Select cocktails made with lower-cal orie mixers, such as seltzer water, fresh citrus juices, or diet sodas, and avoid sugary mixes. Drink water between alcoholic beverages to stay hydrated and help pace your consumption. Consider non-alcoholic alternatives like mocktails or alcohol-free beer or wine to reduce overall alcohol intake. Take your time to enjoy your drink and savor the flavors. Be aware that alcohol provides calories but limited nutrients, so it’s important to factor this into your overall diet. If possible, incorporate alcohol into your meal plan rather than consuming it on an empty stomach to help slow its absorption. Ultimately, making good choices for alcohol consumption within a diet plan involves finding a balance that supports your health goals while allowing for enjoyment. Being informed, mindful, and aware of your choices can help you navigate alcohol consumption in a way that fits into a healthy lifestyle [116].

Monitoring Feces and Urine

Monitoring feces and urine as part of a good choice diet plan can provide valuable insights into your digestive health and overall well-being. Changes in stool consistency, color, odor, and urine output can indicate potential issues or nutritional imbalances. Monitoring stool for consistency whereby a normal stool should be formed but soft, like a banana, and easy to pass. Watery may indicate diarrhea, dehydration, or a digestive issue while hard and dry could signal constipation or a lack of fiber and water in the diet [117].

The stool color; brown is the normal color due to bile pigments; deviations may indicate issues. Green or yellow is often linked to dietary factors or faster transit time or cleansing colors. Red or black could signal bleeding in the upper or lower digestive tract. Mild odor is normal; strong or foul odors could indicate digestive issues or infections. The frequency varies from person to person, but the range is typically 1-3 bowel movements per day to 3 times per week. Significant changes may warrant further investigation [117].

When monitoring urine; pale yellow indicates good hydration levels. Dark yellow or amber may indicate dehydration; increase fluid intake while red or pink could signal blood in the urine or consumption of certain foods such as beets. Urination frequency, normal is typically 6-8 times a day for hydration levels. Excessive urination may indicate underlying medical conditions like diabetes or urinary tract infection.

Urine volume, the normal output is around 1-2 liters per day; affected by fluid intake and diet. Low output could indicate dehydration; consult a healthcare provider if severe. Urine color and odor, clear, odorless indicates good hydration. Cloudy or strong odor may suggest dehydration, infection, or dietary factors [118].

Good choices for diet influencing feces and urine include drinking plenty of water throughout the day to maintain optimal urine output and color [119]. Ensure a balanced diet with adequate fiber to support healthy digestion and stool consistency. Include a variety of nutrient-rich foods to promote overall health and proper bodily function. Reduce intake of processed foods high in sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats that can impact digestive health. Regularly monitoring your feces and urine, along with making informed dietary choices, can help you maintain optimal digestive health and overall well-being. It’s essential to listen to your body, watch for any significant changes, and seek professional advice if you have concerns or persistent symptoms.

Conclusions

Various diet alternatives have been discussed to help individuals make diet decisions. Some may be contradictory and need to be considered individually or combined for total benefits. “The No White Diet” as a dietary regimen can promote good health in a variety of ways. Healthy foods, healthy oils, wise choices for proteins, vegetables, starches, calorie restrictions and preferences to hypoallergenic, hypoglycemic, non-GMO, vegan, keto, alcohol consumption, and monitoring gut health can provide longevity as summarized in Table 4.

Acknowledgements

Dedicated to the memory of Mark Potterbaum, dear friend and colleague.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- (2016) Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition (GloPAN). Food systems and diets: Facing the challenges of the 21st

- Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, Cornaby L, Ferrara G, et al. (2019) Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 393(10184): 1958-1972.

- (2017) High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE). Nutrition and food systems. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. In. Edited by HLPE.

- Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, Kumanyika S, Lobstein T, et al. (2013) INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev 14(1): 1-12.

- Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD (2005) Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot 19(5): 330-333.

- Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I (2012) The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place 18(5): 1172-1187.

- Charreire H, Casey R, Salze P, Simon C, Chaix B, et al. (2010) Measuring the food environment using geographical information systems: a methodological review. Public Health Nutr 13(11): 1773-1785.

- Yamaguchi M, Praditsorn P, Purnamasari SD, Sranacharoenpong K, Arai Y, et al. (2022) Measures of perceived neighborhood food environments and dietary habits: a systematic review of methods and associations. Nutrients 14(9): 1788.

- Sobal J, Bisogni CA, Devine CM, Jastran M (2006) A conceptual model of the food choice process over the life course. In: The psychology of food choice Edn Cabi Wallingford UK 1-18.

- Larson N, Story M (2009) A review of environmental influences on food choices. Ann Behav Med 38(Suppl 1): S56-73.

- Turner C, Aggarwal A, Walls H, Herforth A, Drewnowski A, et al. (2018) Concepts and critical perspectives for food environment research: a global framework with implications for action in low- and middle-income countries. Glob Food Sec 18: 93-101.

- Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson O’Brien R, Glanz K (2008) Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health 29: 253-272.

- Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW (2012) Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev 70(1): 3-21.

- Kant AK, Graubard BI (2007) Secular trends in the association of socio-economic position with self-reported dietary attributes and biomarkers in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1971-1975 to NHANES 1999-2002. Public Health Nutr 10(2): 158-167.

- Sawyer ADM, van Lenthe F, Kamphuis CBM, Terragni L, Roos G, et al. (2021) Dynamics of the complex food environment underlying dietary intake in low-income groups: a systems map of associations extracted from a systematic umbrella literature review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 18(1): 96.

- Westbury S, Ghosh I, Jones HM, Mensah D, Samuel F, et al. (2021) The influence of the urban food environment on diet, nutrition and health outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 6: 10.

- Bivoltsis A, Cervigni E, Trapp G, Knuiman M, Hooper P, et al. (2018) Food environments and dietary intakes among adults: does the type of spatial exposure measurement matter? a systematic review. Int J Health Geogr 17(1): 19.

- Wilkins E, Radley D, Morris M, Hobbs M, Christensen A, et al. (2019) A systematic review employing the GeoFERN framework to examine methods, reporting quality and associations between the retail food environment and obesity. Health Place 57: 186-199.

- An R, He L, Shen MSJ (2020) Impact of neighbourhood food environment on diet and obesity in China: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr 23(3): 457-473.

- Apovian C, Brouillard E, Young, L (2018) Clinical Guide to Popular Diets (1st). CRC Press.

- Ackerberg B (2019) No White Foods Diet: A Beginner's Step by Step Guide with Recipes and a Meal Plan.

- Packer L (2003) The Antioxidant Vitamins C and E (1st). AOCS Publishing.

- Matera R, Lucchi E, Valgimigli L (2023) Plant Essential Oils as Healthy Functional Ingredients of Nutraceuticals and Diet Supplements: A Review. Molecules 28(2): 901.

- Abraham A, Kattoor AJ, Saldeen T, Mehta JL (2019) Vitamin E and its anticancer effects. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 59(17): 2831-2838.

- Niki E (2015) Evidence for beneficial effects of vitamin E. The Korean journal of internal medicine 30(5): 571-579.

- Elagizi A, Lavie CJ, O Keefe E, Marshall K, O Keefe JH, et al. (2021) An Update on Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Health. Nutrients 13(1): 204.

- Salman H B, Salman M A, Yildiz Akal E (2022) The effect of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on weight loss and cognitive function in overweight or obese individuals on weight-loss diet. Nutricion hospitalaria 39(4): 803-813.

- Choi NR, Kim JN, Kwon MJ, Lee JR, Kim SC, et al. (2022) Grape seed powder increases gastrointestinal motility. International journal of medical sciences 19(5): 941-951.

- Turki K, Charradi K, Boukhalfa H, Belhaj M, Limam F, et al. (2016) Grape seed powder improves renal failure of chronic kidney disease patients. EXCLI journal 15: 424-433.

- Sales Campos H, Souza PR, Peghini BC, da Silva JS, Cardoso CR (2013) An overview of the modulatory effects of oleic acid in health and disease. Mini Rev Med Chem 13(2): 201-210.

- Duarte AC, Spiazzi BF, Zingano CP, Merello EN, Wayerbacher LF, et al. (2022) The effects of coconut oil on the cardiometabolic profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Lipids Health Dis 21(1): 83.

- Liepa GU (1992) Dietary Proteins: How They Alleviate Disease and Promote Better Health (1st). AOCS Publishing.

- Bernardo GL, Jomori MM, Fernandes AC, Colussi CF, Condrasky MD, et al. (2017) Nutrition and Culinary in the Kitchen Program: a randomized controlled intervention to promote cooking skills and healthy eating in university students - study protocol. Nutr J 16(1): 83.

- Bender D (1997) An Introduction to Nutrition and Metabolism (2nd). CRC Press.

- Reid I R, Bristow S M, Bolland M J (2015) Calcium supplements: benefits and risks. Journal of Internal Medicine 278: 354-368.

- Ross A C, Manson J E, Abrams S A, Aloia J F, Brannon P M, et al. (2011) The 2011 Report on Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What Clinicians Need to Know. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 96(1): 53-58.

- Calvo MS, Lamberg Allardt CJ (2015) Phosphorus. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md) 6(6): 860-862.

- Serna J, Bergwitz C (2020) Importance of Dietary Phosphorus for Bone Metabolism and Healthy Aging. Nutrients 12(10): 3001.

- Bonet ML, Ribot J, Felipe F, Palou A (2003) Vitamin A and the regulation of fat reserves. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS 60(7): 1311-1321.

- Takahashi N, Saito D, Hasegawa S, Yamasaki M, Imai M (2022) Vitamin A in health care: Suppression of growth and induction of differentiation in cancer cells by vitamin A and its derivatives and their mechanisms of action. Pharmacology & therapeutics 230: 107942.

- Turck D (2013) Cow's milk and goat's milk. World Rev Nutr Diet 108: 56-62.

- Saper R B, Rash R (2009) Zinc: an essential micronutrient. American family physician 79(9): 768-772.

- Skrajnowska D, Bobrowska Korczak B (2019) Role of Zinc in Immune System and Anti-Cancer Defense Mechanisms. Nutrients 11(10): 2273.

- Chen J, Jayachandran M, Bai W, Xu B (2021) A critical review on the health benefits of fish consumption and its bioactive constituents. Food Chem 369: 130874.

- Banting W (1869) Open letter on being overweight. 4th

- Paoli A (2014) Ketogenic diet for obesity: friend or foe?. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11(2): 2092-107.

- Murphy P, Likhodii SS, Hatamian M, McIntyre Burnham W (2005) Effect of the ketogenic diet on the activity level of Wistar rats. Pediatr Res 57(3): 353-357.

- Kossoff EH, Pyzik PL, McGrogan JR, Vining EP, Freeman JM (2002) Efficacy of the ketogenic diet for infantile spasms. Pediatrics 109(5): 780-783.

- Murphy P, Likhodii S, Nylen K, Burnham WM (2004) The antidepressant properties of the ketogenic diet. Biol Psychiatry 56(12): 981-983.

- Seyfried TN, Mukherjee P (2005) Targeting energy metabolism in brain cancer: review and hypothesis. Nutr Metab 2: 30.

- Chester B, Babu JR, Greene MW, Geetha T (2019) The effects of popular diets on type 2 diabetes management. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 35(8): e3188.

- Krebs HA (1996) The regulation of the release of ketone bodies by the liver. Adv Enzyme Regul 4: 339-354.

- Feinman RD, Pogozelski WK, Astrup A, Bernstein RK, Fine EJ, et al. (2015) Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: critical review and evidence base. Nutrition 31(1): 1-13.

- Atkins R (1998) Dr Atkins new diet revolution. New York NY: Avon Books.

- Sears B (1995) The zone: a dietary road map. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

- Agatston A (2005) The south beach diet: the delicious, doctor-designed, foolproof plan for fast and healthy weight loss. New York NY: St. Martin's Press.

- O'Neill B, Raggi P (2020) The ketogenic diet: Pros and cons. Atherosclerosis 292: 119-126.

- McGaugh E, Barthel B (2022) A Review of Ketogenic Diet and Lifestyle. Mo Med 119(1): 84-88.

- Dhamija R, Eckert S, Wirrell E (2013) Ketogenic diet. Can J Neurol Sci 40(2): 158-167.

- Dashti HM, Al Zaid NS, Mathew TC, Al Mousawi M, Talib H, et al. (2006) Long term effects of ketogenic diet in obese subjects with high cholesterol level. Mol Cell Biochem 286(1-2): 1-9.

- Sumithran P, Proietto J (2008) Ketogenic diets for weight loss: a review of their principles, safety and efficacy. Obes Res Clin Pract 2: 1-3.

- Daly ME, Piper J, Paisey R, Darby T, George L, et al. (2006) Efficacy of carbohydrate restriction in obese type 2 diabetes patients. Diabet Med 23(2): 26.

- Boden G, Sargrad K, Homko C, Mozzoli M, Stein TP, et al. (2005) Effect of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite, blood glucose levels, and insulin resistance in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med 142(6): 403-411.

- Nielsen J, Jonsson E (2006) Low-carbohydrate diet in type 2 diabetes. Stable improvement of bodyweight and glycaemic control during 22 months follow-up. Nutr Metab 3: 22-7.

- Ballaban Gil K, Callahan C, ODell C, Pappo M, Moshe S, et al. (1998) Complications of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 39(7): 744-748.

- Bielohuby M, Matsuura M, Herbach N, Kienzle E, Slawik M, et al. (2010) Short-term exposure to low-carbohydrate, high-fat diets induces low bone mineral density and reduces bone formation in rats. J Bone Miner Res 25(2): 275-284.

- Hartman AL, Vining EP (2007) Clinical aspects of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 48(1): 31-42.

- Milder JB, Liang LP, Patel M (2010) Acute oxidative stress and systemic Nrf2 activation by the ketogenic diet. Neurobiol Dis 40(1): 238-244.

- Volek JS, Gomez AL, Kraemer WJ (2000) Fasting and postprandial lipoprotein responses to a low-carbohydrate diet supplemented with n-3 fatty acids. J Am Coll Nutr 19: 383-391.

- Vamecq J, Vallee L, Lesage F, Gressens P, Stables JP (2005) Antiepileptic popular ketogenic diet: emerging twists in an ancient story. Prog Neurobiol 75: 1-28.

- Alnasser A, Almutairi M (2022) Considering intermittent fasting among Saudis: insights into practices. BMC Public Health 22(1): 592.

- De Cabo R, Mattson MP (2019) Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease. N Engl J Med 381(26): 2541-2551.

- Patterson RE, Laughlin GA, LaCroix AZ, Sheri J Hartman, Loki Natarajan, et al. (2015) Intermittent fasting and human metabolic health. J Acad Nutr Diet 115: 1203-1212.

- Longo VD, Mattson MP (2014) Fasting: molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Cell Metab 19(2): 181-192.

- Johnson JB, Summer W, Cutler RG, Bronwen Martin, Dong Hoon Hyun, et al. (2007) Alternate day calorie restriction improves clinical findings and reduces markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in overweight adults with moderate asthma. Free Radic Biol Med 42(5): 665-674.

- Anton SD, Moehl K, Donahoo WT, Krisztina Marosi, Stephanie Lee, et al. (2018) Flipping the metabolic switch: understanding and applying the health benefits of fasting. Obesity (Silver Spring) 26(2): 254-268.

- Elias A, Padinjakara N, Lautenschlager NT (2023) Effects of intermittent fasting on cognitive health and Alzheimer's disease. Nutr Rev 81(9): 1225-1233.

- Cahill GF Jr (1970) Starvation in man. N Engl J Med 282(12): 668-675.

- Browning JD, Baxter J, Satapati S, Shawn C Burgess (2012) The effect of short-term fasting on liver and skeletal muscle lipid, glucose, and energy metabolism in healthy women and men. J Lipid Res 53(3): 577-586.

- Harvie MN, Pegington M, Mattson MP, J Frystyk, B Dillon, et al. (2011) The effects of intermittent or continuous energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers: a randomized trial in young overweight women. Int J Obes 35(5): 714-727.

- Gabel K, Kroeger CM, Trepanowski JF, Kristin K Hoddy, Sofia Cienfuegos, et al. (2019) Differential effects of alternate-day fasting versus daily calorie restriction on insulin resistance. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 27: 1443-1450.

- Weyer C, Bogardus C, Mott DM, R E Pratley (1999) The natural history of insulin secretory dysfunction and insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 104: 787-794.

- Kitabchi AE, Temprosa M, Knowler WC, Steven E Kahn, Sarah E Fowler, et al. (2005) Role of insulin secretion and sensitivity in the evolution of type 2 diabetes in the diabetes prevention program: effects of lifestyle intervention and metformin. Diabetes 54(8): 2404-2414.

- Tabák AG, Jokela M, Akbaraly TN, Eric J Brunner, Mika Kivimäki, et al. (2009) Trajectories of glycaemia, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the Whitehall II study. Lancet 373: 2215-2221.

- Muoio DM, Newgard CB (2008) Molecular and metabolic mechanisms of insulin resistance and β-cell failure in type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9(3): 193-205.

- Gast KB, Tjeerdema N, Stijnen T, Johannes W A Smit, Olaf M Dekkers, et al. (2012) Insulin resistance and risk of incident cardiovascular events in adults without diabetes: meta-analysis. PLoS One 7: E 52036.

- Merimee TJ, Fineberg ES (1966) Starvation-induced alterations of circulating thyroid hormone concentrations in man. Metabolism 25(1): 79-83.

- Mattson MP, Arumugam TV (2018) Hallmarks of brain aging: adaptive and pathological modification by metabolic states. Cell Metab 27(6): 1176-1199.

- Heine RG (2018) Food Allergy Prevention and Treatment by Targeted Nutrition. Ann Nutr Metab 72 Suppl 3: 33-45.

- Du Toit G, Foong RM, Lack G (2016) Prevention of food allergy-early dietary interventions. Allergol Int 65(4): 370-377.

- Fiocchi A, Assa’ad A, Bahna S (2006) Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology: Food allergy and the introduction of solid foods to infants: a consensus document. Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee, American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 97: 10-20.

- Lack G, Golding J (1996) Peanut and nut allergy. Reduced exposure might increase allergic sensitisation. BMJ 313(7052): 300.

- Burbank AJ, Sood P, Vickery BP, Wood RA (2016) Oral immunotherapy for food allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 36: 55-69.

- Aitoro R, Paparo L, Amoroso A, Di Costanzo M, Cosenza L, et al. (2017) Gut microbiota as a target for preventive and therapeutic intervention against food allergy. Nutrients 9(7): 672.

- Craig WJ (2018) Vegetarian Nutrition and Wellness (1st ed.). CRC Press.

- Wu G (2010) Amino Acids: Biochemistry and Nutrition (1st ed.). CRC Press.

- Ludwig DS (2002) The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA 287(18): 2414-2423.

- Aude Y, Agatston A, Lopez Jimenez F, Lieberman E, Almon M, et al. (2004) The National Cholesterol Education Program Diets a diet lower in carbohydrates and higher in protein and monounsaturated fat: a randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine 164(19): 2141-2146.

- Benassi Evans B, Clifton P, Noakes M, Keogh J, Fenech M, et al. (2009) High protein–high red meat versus high carbohydrate weight loss diets do not differ in effect on genome stability and cell death in lymphocytes of overweight men. Mutagenesis 24(3): 271-277.

- Buksh SM, Hay P, John B F de Wit (2023) Perceptions on Healthy Eating Impact the Home Food Environment: A Qualitative Exploration of Perceptions of Indigenous Food Gatekeepers in Urban Fiji. Nutrients 15(18): 3875.

- Skrovankova S, Sumczynski D, Mlcek J, Jurikova T, Sochor J (2015) Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Different Types of Berries. Int J Mol Sci 16;16(10): 24673-24706.

- Borghi SM, Pavanelli WR (2023) Antioxidant Compounds and Health Benefits of Citrus Fruits. Antioxidants (Basel) 12(8): 1526.

- Sayago Ayerdi S, García Martínez DL, Ramírez Castillo AC, Ramírez Concepción HR, Viuda Martos M (2021) Tropical Fruits and Their Co-Products as Bioactive Compounds and Their Health Effects: A Review. Foods 22;10(8): 1952.

- Liu RH (2013) Health-promoting components of fruits and vegetables in the diet. Adv Nutr 4(3): 384S-92S.

- Leonard Sonnenschein, Tiberious Etyang, Ivan E (2024) Rodriguez Histamine Over-Activation Alleviation Using Dietary Supplements. Am J Biomed Sci & Res 22(2).

- Leonard Sonnenschein, Tiberious Etyang (2024) Pain Management, Pathogenicity and Healing Using Dietary Supplements for Wellness. Am J Biomed Sci & Res 22(1): 148-163.

- Leonard Sonnenschein, Tiberious Etyang (2024) The Medical Importance of Activated Carbon for Detoxing. Am J Biomed Sci & Res 21(4): 397-401.

- Leonard Sonnenschein, Tiberious Etyang (2024) T Cell Activation by Natural Mechanisms. Am J Biomed Sci & Res 21(6).

- Mah E, Chen O, Liska DJ, Blumberg JB (2022) Dietary Supplements for Weight Management: A Narrative Review of Safety and Metabolic Health Benefits. Nutrients. 14(9): 1787.

- Rizzoli R (2021) Vitamin D supplementation: upper limit for safety revisited ? Aging Clin Exp Res 33(1): 19-24.

- Deldicque L, Francaux M (2016) Potential harmful effects of dietary supplements in sports medicine. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 19(6): 439-445.

- Myette Côté É, Durrer C, Neudorf H, Bammert TD, Botezelli JD, et al. (2018) The effect of a short-term low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet with or without postmeal walks on glycemic control and inflammation in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 1;315(6): R1210-R1219.

- Ballmer Weber BK (2000) Die hypoallergene Diät [The hypo-allergic diet]. Ther Umsch 57(3): 121-127.

- Rodgers S (2016) Minimally Processed Functional Foods: Technological and Operational Pathways. J Food Sci 81(10): R2309-R2319.

- Dauria E, Salvatore S, Acunzo M, Peroni D, Pendezza E, Et Al. (2021) Hydrolysed Formulas In The Management Of Cow's Milk Allergy: New Insights, Pitfalls And Tips. Nutrients 13(8): 2762.

- Kovář J, Zemánková K (2015) Moderate alcohol consumption and triglyceridemia. Physiol Res 64(3): 371-375.

- Yan Z, Liu Y, Zhang T, Zhang F, Ren H, et al. (2022) Analysis of Microplastics in Human Feces Reveals a Correlation between Fecal Microplastics and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Status. Environ Sci Technol 4;56(1): 414-421.

- Rigby D, Gray K (2005) Understanding urine testing. Nurs Times 101(12): 60-2.

- Salas Salvadó J, Maraver Eizaguirre F, Rodríguez Mañas L, Saenz de Pipaón M, Vitoria Miñana I, et al. (2020) The importance of water consumption in health and disease prevention: the current situation. Nutr Hosp 37(5): 1072-1086.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.