Commentary

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Gives Mammographic Screening False Reassurance to Women?

*Corresponding author: Guy Storme, Depatment of Radiiation Oncology UZ Brussel, Asfilstraat 20, 9031 Drongen, Belgium.

Received: October 10, 2024; Published: October 18, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.24.003202

Abstract

Despite many new, extremely expensive medications are employed, there is no effect on the relative survival of patients, even the enormous number of articles on breast cancer screening that are released over time using various time sequences and approaches. This brief statement raised concerns about the effectiveness of screening as well as screening methodology.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women and one of the most significant causes of death, representing a major world public health problem [1]. Due to early detection programs, as well as advances in treatment, death rates for breast cancer have recently been declining, but this cancer still represents a leading cause of deaths for women in most countries [2]. Breast cancer detecting a lesion before it negatively affects the prognosis is the aim of breast cancer screening (BCS), and the smaller the tumor, the better the prognosis [3]. The number of deaths in all phases combined was >50% fewer in screen-detected cases than in non-screen-detected cases, according to an early benefit of BCS [4]. The advice offered makes sense because it is derived from over 40 years of experience [5]. Nonetheless, an analysis of women 50 years of age or older enrolled in the Ontario Breast Screening Program revealed that interval cancers, which are defined as breast cancers detected within 24 months following a negative screening mammography, were called true interval cancers (also known as missed intervals) if they were missed during screening but discovered later compared to tumors seen on screens, interval cancers had higher stages and grades. The additional unfavorable predictive characteristics of non- ductal shape and negative for the estrogen and progesterone receptors were more prevalent in true interval tumors [6]. Even older screening mammographs were used, the study by Miller et al after 25 years of follow-up in a randomized breast cancer screening research study among patients who were instructed by qualified nurses or doctors to perform monthly breast self-examinations instead of mamo-echography, we still lack evidence that mamo- and or echography brings an added value. Over this period, 89,835 women were followed up, and the cumulative breast cancer mortality did not differ statistically between the two groups. In the first year, there was a significant difference in the number of deaths linked to breast cancer in the mamo-echography group (p = 0.04), but in the first five years, there was no difference (P = 0.40). The control group’s mean tumor diameter was 2.1 cm. In the mamo-echography group the palpable was 2.1cm, the non-palpable was 1.4 cm and the mean 1,9 cm. There were no changes in the overall or mortality specific to breast cancer between the mammography and control groups, with 108.4 and 110.2 deaths per 10,000 women, respectively [7]. Analyzing data found that mammography and echo- radiography were not useful compared to a standard physical examination; they may even be harmful due to a substantial degree of overdiagnosis from mammography screening. Overdiagnosis of the order of 30% for women aged 40-49 and 20% for women aged 50-59 was observed and mainly in situ were over diagnosed [8]. New approaches compared mammography screening modalities (mammography with or with- out digital breast tomosynthesis [DBT]), different screening strategies with respect to interval, age to start, age to stop, or supplemental screening strategies using ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with mammography were inconclusive because key studies have not yet been completed and few studies have reported the stage shift or mortality outcomes necessary to assess relative benefits [9]. Despite a huge number of new treat ments having increased survival rates, we don’t observe between 2000 and 2020, an influence on relative survival which was the case between 1975 and 2000 were screening was initiated [10]. Additionally, screening in the same period has led to a stage shift, which has improved survival rates in and of itself, but it is unclear which of the two has the greatest impact: screening or treatment. Similar to Miller’s study, mamo- and echography were not as beneficial as a routine monthly physical examination, benefice of screening in general can be put in question since randomized trials on most organs show no benefit with exception of sigmoidoscopy for colon cancer [11]. Every woman should know that self-examination removes the need for radiologic equipment, lessens anxiety about radiation, pain, and discomfort, and lessens fear of screening results as undesired, but potentially treatable, aspects of breast cancer screening anxiety [12]. For society self-examination could save a significant amount of money on medical expenses of about 2.6 billion bi-annual mammography examination [13]. It is also notable that screening is less performed in older patients where the incidence/100,000 is greatest at the age of 75 years [14]. Observing no improvement in RS, could it be that some benefices of treatment are lost due to side effects as for older women, CVD poses a greater mortality threat than breast cancer itself [15].

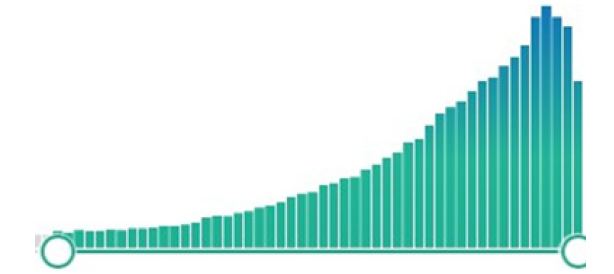

Should we go on with and who should foot the bill for at least breast cancer screening despite we have 167427 mentioned publications in PubMed (Figure 1) and no improvement of outcome on population bases.

Figure 1: Evolution of number of publications: articles found with keywords “breast cancer screening” reaching 163856 using PubMed between 1975 and till September 2024 reaching a peak in 2021.

It begs the question: Who should foot the bill for cancer screening tests, and shouldn’t the discussion be around individual benefit rather than population support?

Funding

This Article was supported by ONCOTEST.

Acknowledgments

Prof Marc Mareel for advice.

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel R, et al., (2024) Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 74(3): 229-263.

- Rojas K, Stuckey A (2016) Breast Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol 59(4): 651-672.

- Liu Y, He M, Zuo W, Hao S, Wang Z, et al., (2021) Tumor size still impacts prognosis in breast cancer with extensive nodal involvement. Front Oncol 11, 585613.

- Morrison AS, Brisson J, Khalid N (1988) Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the Breast Cancer Detection Demonstration Project. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 80(19): 1540-1547.

- Margarita L Zuley, Andriy I Bandos, Stephen W Duffy, Durwin Logue, Rohit Bhargava, et al., (2024) Breast Cancer Screening Interval: Effect on Rate of Late-Stage Disease at Diagnosis and Overall Survival. J Clin Oncol.

- Kirsh V, Chiarelli A, Edwards S, O Malley F, Shumak R, et al., (2011) Tumor characteristics associated with mammographic detection of breast cancer in the Ontario breast screening program. J Natl Cancer Inst 103(12): 942-550.

- Miller AB, Wall C, Baines C, Sun P, To T, (2014) Twenty-five years follow-up for breast cancer incidence and mortality of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study: Randomized screening trial. BMJ 348.

- Baines CJ, To T, Miller A, (2016) Revised estimates of overdiagnosis from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. Prev Med 90: 66-67.

- Henderson J, Webber E, Weyrich M, Miller M, Melnikow J (2024) Screening for Breast Cancer Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 331(22):1931-1946.

- Storme G (2024) Are we losing the final fight against cancer? Cancers 16(2): 421.

- Bretthauer M, Wieszczy P, Løberg M, Kaminski M, Werner T, et al., (2023) Estimated Lifetime Gained with Cancer Screening Tests a Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Intern Med 183(11): 1196-1203.

- Burugu V, Salvatore M (2024) Exploring breast cancer screening fear through a psychosocial lens. Eur J Cancer Prev.

- (2020) Cancer Control.

- (2023) SEER Incidence Data (1975-2021).

- Mehta L, Watson K, Barac A, Beckie T, Bittner V, et al., (2018) Cardiovascular disease and Breast Cancer: Where These Entities Intersect: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 137: e30-e66.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.