Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Medication Non-Adherence Prevalence and Determinants among internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Wad Madani Camps 2023: A Cross-Sectional Study

*Corresponding author: Sawsan A. Omer, Faculty of Medicine, University of Gezira, Sudan and Wad Medani Teaching Hospital, Sudan.

Received: November 05, 2024; Published: November 12, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.24.003240

Abstract

Background: Medication non-adherence (MNA) is a significant issue, particularly among patients with chronic diseases, leading to adverse health outcomes and increased healthcare costs. Internally displaced persons (IDPs) face unique challenges that may exacerbate non-adherence. This study aimed to assess the prevalence and determinants of MNA among IDPs in Wad Madani camps, Gezira, Sudan 2023.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in October 2023, involving 400 IDPs diagnosed with chronic diseases in Wad Madani camps. Data were collected using a well-structured questionnaire covering demographics, type and duration of chronic diseases, and medication adherence behaviours. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.

Results: The majority of participant were females 291 (72.8%) and most of participants, 107 (26.7%) were in the age group of 41-50. The study revealed a 55% prevalence of MNA among participants. Key determinants included unavailability of medications (42.8%), high costs (30%), and forgetfulness. The majority of the study population had low educational levels, with 37.5% having only primary education. Financial constraints were significant, with 81% of participants reporting no monthly income. Additionally, 88.3% did not receive community support, and 31.5% had no access to counselling or educational sessions regarding their diseases and medications.

Conclusions: This study provides valuable insights into the prevalence and determinants of medication non-adherence among IDPs in Wad Madani camps. The high rates of non-adherence and the identified barriers underscore the need for targeted interventions to improve medication adherence in this vulnerable population. Financial support, improved access to medications, and comprehensive patient education and counseling are essential components of such interventions. Future research should focus on developing and evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions to enhance the health outcomes of IDPs with chronic diseases.

Keywords: Medication non-adherence, Internally displaced persons, Chronic diseases, Wad Madani camps, Sudan, Medication adherence determinants, Healthcare barriers

Introduction

Medication non-adherence (MNA) is a significant public health concern, particularly among patients with chronic illnesses. Non-adherence rates for patients undergoing chronic treatment courses are alarmingly high and have been linked to various adverse outcomes, including treatment failure, deterioration in health, and increased healthcare costs [1,2]. Studies have demonstrated that adherence to prescribed medication regimens is crucial for managing chronic diseases effectively, reducing complications, hospital admissions, and healthcare costs [3]. Despite these benefits, adherence rates in developed nations for long-term therapy average around 50% and decline sharply after the first six months, especially for non-symptomatic conditions or diseases with inactive periods [4,5]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), medication adherence is essential for improving health outcomes in chronic disease management [6]. The WHO’s 2003 report highlights that 50% of chronic disease patients do not adhere to their prescribed medication regimens, underscoring the global scale of this issue [6]. The Global Burden of Disease (2010) report further emphasizes that non-communicable diseases (NCDs) have surpassed communicable diseases as the leading cause of death worldwide. By 2025, it is projected that chronic illnesses will cause 3.87 million premature deaths annually [7]. Several factors contribute to MNA, including the complexity of medication regimens, side effects, forgetfulness, lack of understanding of the disease or treatment, and financial constraints [8,9]. Studies have shown that financial barriers, such as out-of-pocket expenses, are significant determinants of MNA, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [10]. For instance, a study in Karachi, Pakistan, identified financial constraints as a major barrier to medication adherence among chronic illness patients [11]. Similarly, a systematic review highlighted the effectiveness of mobile phone text messaging in improving medication adherence, suggesting that reminders can help overcome forgetfulness and enhance adherence rates [12]. Non-adherence can be either inadvertent, due to unforeseen behaviours, or deliberate, representing a conscious decision influenced by the patient’s beliefs and mental state [13]. Understanding these underlying factors is crucial for developing tailored interventions to improve adherence. A meta-analysis found a strong association between medication adherence and reduced mortality rates, emphasizing the importance of adherence for patient survival [14]. Interventions to improve medication adherence have been extensively studied. A systematic review by Kripalani, et al. (2007) identified several effective strategies, including patient education, medication reminders, and simplified drug regimens [15]. Despite these interventions, there is no consensus on a gold standard approach, and the effectiveness of strategies varies based on individual patient needs and contexts [16].

Research on IDPs highlights additional challenges to medication adherence. Displacement often exacerbates barriers to healthcare access, including medication availability, financial constraints, and instability [17]. A study on IDPs in Syria found that the majority faced difficulties in accessing medications due to the ongoing con flict and displacement [18]. In Sudan, similar challenges are likely present among IDPs, impacting their ability to adhere to chronic disease treatments. This study aimed to assess the prevalence and determinants of MNA among IDPs in Wad Madani camps, Gezira, Sudan 2023.

Materials and Methods

This study used a cross-sectional community-based approach, it was conducted in October 2023 to examine the prevalence and determinants of medication non-adherence of four hundred (400) individuals diagnosed with chronic diseases, living in internally displaced camps in Wad Madani, Gezira, Sudan in 2023. Well-structured questionnaire, based on previous similar studies, had been developed to collect data from patients affected with chronic diseases in Wad Madani camps. It consisted of different domains included the following information: (age, gender, marital status, Educational level, Occupation, Monthly income, type of chronic disease, duration of chronic disease, types and number of medication used). Data was collected by medical students from University of Gezira. Students from different batches participated in data collection after training on the method of questionnaire filling. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 22.

Selection Criteria for the Study

Internally displaced persons with chronic disease in Wad Madani camps of all ages, who were willing to participant in the study and able to provide verbal consent.

Exclusion Criteria

included individuals without chronic diseases, those who were not internally displaced or residing outside Wad Madani Camps. Unwillingness to participate in the study or unable to provide verbal consent.

Ethical Considerations

The research was conducted within the ethical supervision the Faculty of Medicine, University of Gezira and Ministry of Health, Gezira State, ethical committee. Verbal informed consent was obtained from those who were willing to participate in the research following adequate explanation of aim, procedures, benefits and possible risks were included in the study. There was no penalty for refusal or participate.

Results

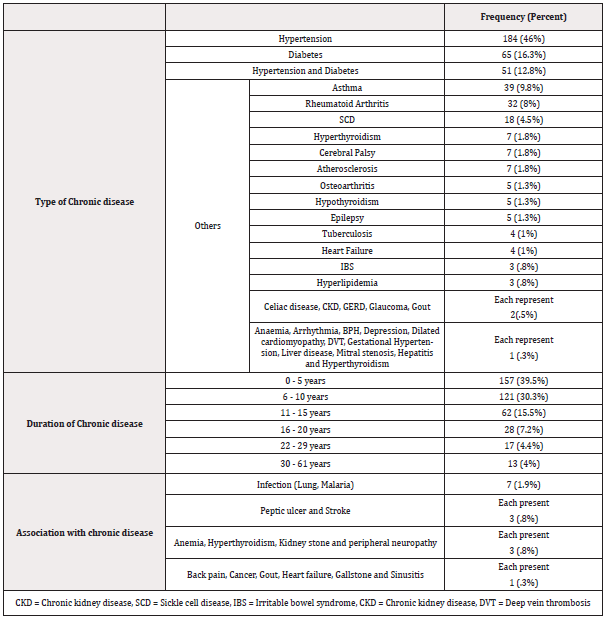

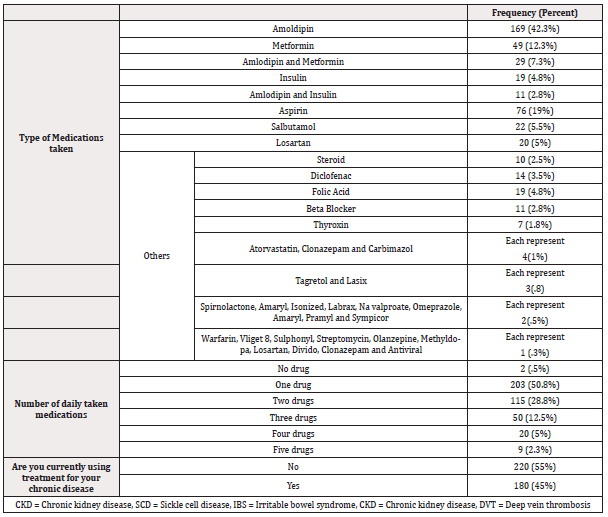

In this cross- sectional community based study, 400 participants were enrolled. The majority were females 291 (72.8%) and 109 (27.3%) were males. 107 (26.7%) of participants were in the age group of 41-50 years of age, 94 (23.5%) were with age group [51-60], 66 (16.5%), [31-40], 43 (10.7%), [ 21-30], 34 (8.5%), [60- 70], 28 (7%), [71-90], 26 (6.5%), [11-20] and 10 (2.5%) in the age group [ 5-10] years old. Regarding marital status 307 (76.8%) were married, 68 (17%) were single and 25 (6.3%) were divorced. In terms of educational level, the majority of participants had only primary education 150 (37.5%), then 114 (28.5%) had no formal education, 88 (22%) had secondary education and 44 (11%) had tertiary education. More than half of women participated in this study were housewife 154 (38.6%), 102 (25.5%) of participants were unemployed. 324 (81%) had no monthly income at all. Half of participants 203 (50.8%) with chronic disease were using at least one drug (Table 1), followed by 115 (28.8%), 50 (12.5%), 20 (5%) and 9 (2.3%) who were using two, there, four and five drugs respectively (Table 2). 304 (76%) faced challenges in accessing their medications after the war due to many factors mostly to unavailability of medication 171 (42.8%) and expensive cost 120 (30%). Furthermore 220 (55%) of participants were not taking their prescribed drugs. Most of patients who can afford their prescribed drugs rarely missed them 248 (62%). Forgetfulness was the most common cause of missing or skipping their medication. 73 (18.3%) of the participants if their doctors prescribed the same medication but from other company they didn’t take them. Out of 400 participants, 353 (88.3%) of them didn’t receive any support from any community resources or programs. Furthermore 126 (31.5%) of participants didn’t received any counselling or educational sessions towards their disease and medications.

Discussion

The results of this study highlight the significant issue of medication non-adherence (MNA) among internally displaced persons (IDPs) with chronic diseases in Wad Madani camps. The prevalence of non-adherence was found to be 55%, which is in line with the World Health Organization’s estimation that 50% of patients with chronic conditions do not adhere to their prescribed medications [19]. This high rate of non-adherence is concerning, given the associated negative clinical outcomes and increased healthcare costs [20,21].

Several determinants of non-adherence were identified in this study, including unavailability of medication (42.8%), high medication costs (30%), and forgetfulness. These factors are consistent with findings from other studies that have examined barriers to medication adherence. For instance, a study conducted in Karachi, Pakistan, also identified financial constraints as a major barrier to medication adherence among patients with chronic illnesses [22]. Similarly, a review by Sarabi, et al. (2016) emphasized that medication costs and regimen complexity are significant obstacles to adherence [23].

The demographic characteristics of the study participants further elucidate the context of MNA. The majority of the participants were female (72.8%), with a significant proportion having only primary education (37.5%) or no formal education (28.5%). These factors may contribute to poor health literacy, which has been shown to affect medication adherence negatively [24]. Moreover, the high unemployment rate (25.5%) and lack of monthly income (81%) among participants likely exacerbate financial barriers to accessing medication.

Interestingly, the study found that 62% of participants who could afford their prescribed medications rarely missed their dos es, highlighting the critical role of financial support in enhancing adherence. This finding is supported by a study by Naqvi, et al. (2019), which indicated that financial assistance and community support could significantly improve medication adherence among patients with chronic illnesses [22].

In comparison to similar studies on displaced populations, the findings of this study align with research conducted among Syrian refugees in Jordan, which reported substantial barriers to accessing healthcare and medications due to financial constraints and instability [25]. Furthermore, a study on IDPs in Yemen found that ongoing conflict and displacement significantly hindered access to healthcare services, including essential medications [26]. These studies underscore the unique challenges faced by displaced populations in managing chronic diseases.

The lack of community support and counseling services for the participants in this study is also noteworthy. Only 11.7% of participants received support from community resources, and 31.5% received counseling or educational sessions regarding their disease and medications. These findings suggest a gap in the provision of comprehensive healthcare services to IDPs, which is crucial for improving medication adherence and overall health outcomes. Kripalani, et al. (2007) highlighted that patient education and support are effective strategies for enhancing medication adherence [27]. Therefore, implementing community-based interventions and educational programs could be beneficial for this population.

Conclusion

This study underscores the critical issue of medication non-adherence (MNA) among internally displaced persons (IDPs) with chronic diseases in Wad Madani camps. The findings reveal a high prevalence of non-adherence, with more than half of participants not taking their prescribed medications. Factors such as unavailability of medications, high costs, forgetfulness, and lack of community support significantly contribute to this non-adherence. These barriers are consistent with findings from similar studies on displaced populations and chronic disease management. The demographic profile of the participants, characterized by low educational levels and high rates of unemployment, further complicates the adherence landscape. The absence of adequate community support and counseling services exacerbates the problem, highlighting the need for comprehensive healthcare strategies tailored to the unique challenges faced by IDPs.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, the following recommendations are proposed to address the issue of medication non-adherence among IDPs in Wad Madani camps: Enhance Medication Availability and Affordability. Implement Educational and Counselling Programs. Strengthen Community Support Systems. Conduct Further Research.

Limitations of the Study

i. Cross-Sectional Design.

ii. Self-Reported Data: The reliance on self-reported data for measuring medication adherence and other variables may introduce bias, such as social desirability bias or recall bias, potentially leading to over- or under-estimation of adherence rates.

iii. External Factors: The study did not account for external factors such as political instability, environmental conditions, or recent changes in healthcare policies, which might influence medication adherence among IDPs.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all the participants from the IDPs individuals as well as supervisors of the campuses for IDPs people. Thanks extended to the medical students from different Batches for their help in the study. Special thanks to the administrators of Faculty of Medicine, particularly the dean of the faculty Dr. Wail Nouri.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest

All authors have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from faculty of Medicine, University of Gezira and Ministry of Health, Gezira State, ethical committee as well as informed verbal consent from all participants.

Funding

The Authors and participants did not receive any type of funding.

References

- (2023) World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO.

- Balkrishnan R (1998) Predictors of medication adherence in the elderly. Clin Ther 20(4): 764-771.

- Monnette A, Zhang Y, Shao H, Shi L (2018) Concordance of Adherence Measurement Using Self-Reported Adherence Questionnaires and Medication Monitoring Devices: An Updated Review. Pharmaco Economics 36(1): 17-27.

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 353(5): 487-497.

- Hughes CM (2004) Medication non-adherence in the elderly: how big is the problem? Drugs Aging 21(12): 793-811.

- Sabate´ E (2003) Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation, 2003.

- Jafar TH, Haaland BA, Rahman A, Razzak JA, Bilger M, et al. (2013) Non-communicable diseases and injuries in Pakistan: strategic priorities. Lancet 381(9885): 2281-2290.

- Sarabi R E, Sadoughi F, Orak R J, Bahaadinbeigy K (2016) The effectiveness of mobile phone text messaging in improving medication adherence for patients with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Iran Red Crescent Med J 18(5): e25183.

- Simpson SH, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, Rajdeep S Padwal, Ross T Tsuyuki, et al. (2006) A meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortality. BMJ 333(7557): 15.

- Murray MD, Morrow DG, Weiner M, Clark DO, Tu W, et al. (2004) A conceptual framework to study medication adherence in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2(1): 36-43.

- Naqvi AA, Hassali MA, Aftab MT, Muhammad Nehal Nadir (2019) A qualitative study investigating perceived barriers to medication adherence in chronic illness patients of Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc 69(2): 216-223.

- Hugtenburg JG, Timmers L, Elders PJM, Marcia Vervloet, Liset van Dijk (2013) Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: a challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Prefer Adher 7: 675-682.

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 353(5): 487-497.

- Simpson SH, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, Rajdeep S Padwal, Ross T Tsuyuki, et al. (2006) A meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortality. BMJ 333(7557): 15.

- Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes RB (2007) Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 167(6): 540-550.

- Hughes CM (2004) Medication non-adherence in the elderly: how big is the problem? Drugs Aging 21(12): 793-811.

- Koum Besson ES, Norris A, Bin Ghouth AS, Freemantle SJ, Dureab F, et al. (2021) Experiences of healthcare access in Yemen during conflict: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 11: e045425.

- Doocy S, Lyles E, Akhu-Zaheya L, Oweis A, Al Ward N, et al. (2016) Health service access and utilization among Syrian refugees in Jordan. Int J Equity Health 15: 108.

- (2003) World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO.

- Balkrishnan R (1998) Predictors of medication adherence in the elderly. Clin Ther 20(4): 764-771.

- Monnette A, Zhang Y, Shao H, Shi L (2018) Concordance of Adherence Measurement Using Self-Reported Adherence Questionnaires and Medication Monitoring Devices: An Updated Review. Pharmaco Economics 36(1): 17-27.

- Naqvi AA, Hassali MA, Aftab MT, Muhammad Nehal Nadir (2019) A qualitative study investigating perceived barriers to medication adherence in chronic illness patients of Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc 69(2): 216-223.

- Sarabi R E, Sadoughi F, Orak R J, Bahaadinbeigy K (2016) The effectiveness of mobile phone text messaging in improving medication adherence for patients with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Iran Red Crescent Med J 18(5): e25183.

- Hughes CM (2004) Medication non-adherence in the elderly: how big is the problem? Drugs Aging 21(12): 793-811.

- Doocy S, Lyles E, Akhu-Zaheya L, Oweis A, Al Ward N, et al. (2016) Health service access and utilization among Syrian refugees in Jordan. Int J Equity Health 15: 108.

- Koum Besson ES, Norris A, Bin Ghouth AS, Freemantle SJ, Dureab F, et al. (2021) Experiences of healthcare access in Yemen during conflict: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 11: e045425.

- Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes RB (2007) Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 167(6): 540-550.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.