Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Novel Approach to Fractional Radiofrequency Microneedling: Optimizing Patient Experience

*Corresponding author: Diane Duncan, MD, FACS, Plastic Surgical Associates, Fort Collins CO, 1701 East Prospect Road, USA.

Received: October 29, 2024; Published: November 05, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.24.003227

Abstract

Introduction: One of the popular minimally invasive procedures is Fractional Radiofrequency Microneedling (FRMN). The procedure offers minimal downtime, safety and is suitable for darker skin types. However, the major drawback of FRMN is pain. A novel FRMN device has been developed, specifically to improve the discomfort associated with therapy, while sustaining treatment efficacy.

Aim: This pilot investigation aims to assess the therapy comfort of the novel FRMN device and its efficacy and safety.

Materials and Methods: In this prospective, single-center, open-label study, 14 subjects were enrolled. Ten subjects underwent facial treatments, from which five (n=5, 65.6±6 years, skin type I-III) for treating rhytids and five (n=5, 35±11.6 years, skin type II-IV) for acne scars. Four (n=4, 35.3±6.1 years, skin type I-III) subjects were enrolled for treating body striae on the abdomen. Each subject received three treatments, spaced 7-14 days apart. Comfort and satisfaction were assessed using questionnaires, and efficacy using GAIS evaluation.

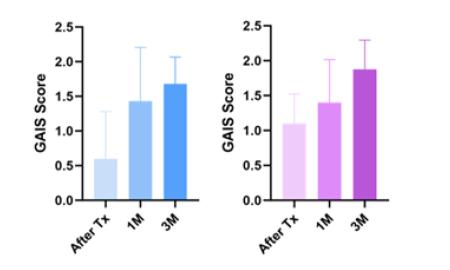

Results: The NRS evaluation revealed an average score of 3.7/10 across all three treatments. 79% of subjects reported the treatment as comfortable. There was a statistically significant aesthetic improvement after the treatments. Facial treatment subjects had an average improvement of 1.7 points, while the body striae subjects had an average improvement of 1.9 points 3 months post-treatment according to GAIS. The subject satisfaction questionnaire revealed high patient satisfaction.

Conclusion: Study results suggest the Fractional Radiofrequency Microneedling procedure with the novel device is comfortable while sustaining therapy efficacy demonstrated in the treatment of rhytids, acne scars, and body striae.

Keywords: Skin, Wrinkle, Acne scars, Striae, Stretch marks, Radiofrequency, Microneedling, fractional

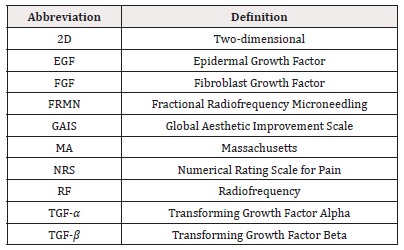

Abbreviations: 2D: Two-dimensional; EGF: Epidermal Growth Factor; FGF: Fibroblast Growth Factor; FRMN: Fractional Radiofrequency Microneedling; GAIS: Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale; MA: Massachusetts; NRS: Numerical Rating Scale for Pain; RF: Radiofrequency; TGF-α: Transforming Growth Factor Alpha; TGF-β: Transforming Growth Factor Beta

Introduction

The contemporary societal emphasis on physical aesthetics has resulted in the rise of interest in cosmetic procedures, especially those non-surgical procedures with minimal downtime. In 2022, within the United States exclusively, the number of minimally invasive cosmetic procedures performed increased to 23.6 million compared to 15.8 million in 2020 [1,2]. One of the popular minimally invasive procedures is microneedling. Microneedling emerged in the 90s for the treatment of scars and became popular during the 00s for skin rejuvenation [3]. This procedure uses an array of needles to create micro-injuries in the dermis, triggering the non-inflammatory regeneration processes [4], and subsequently the release of growth factors, such as Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF), Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF), Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), and transforming growth factor alpha and beta (TGF-𝛼 and TGF-𝛽) [5,6].

These growth factors are suggested to play a role in the increased collagen and elastin production as well as fiber reorganization observed after the microneedling treatments [7]. To enhance efficacy, Fractional Radiofrequency Microneedling (FRMN) was developed, combining the mechanical stimulation of microneedling and the thermal effect of radiofrequency. Radiofrequency has been widely used in cosmetic dermatology for facial rejuvenation through collagen and elastin promotion [8]. FRMN has proven its efficacy for multiple indications such as the treatment of wrinkles, acne scars, striae distensae, axillary hyperhidrosis or alopecia [9]. The treatment offers minimal downtime, safety, and is suitable for darker skin types (up to Fitzpatrick skin type VI [10,11]. As the radiofrequency energy is not absorbed by chromophores [8], the risk of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation is minimized.

The major drawback of FRMN, however, is pain. The pain can sometimes reach such an intensity that averts patients from completing scheduled treatment sessions or limits the needle depth insertion necessary for adequate efficacy, especially of body treatments, where the dermis is thicker compared to the face [12,13]. Increased pain with needle depth has been demonstrated by previous research [14,15]. To reduce discomfort, the procedure is often accompanied by different types of anesthetics, starting from topical anesthetics to nerve blocks, oral narcotics, or nitrous oxide/oxygen inhalation when topical anesthetic is insufficient9. Traditional FRMN procedures, moreover, exacerbate irritation to the already compromised skin due to multiple passes over the same area, required for their efficacy. To combat FRMN disadvantages, a novel FRMN device has been developed, specifically to improve the discomfort associated with therapy, while sustaining therapy efficacy. According to real-time impedance measurements derived from each needle, the device’s algorithms adjust pulse parameters individually tailored to each patient and treatment area, ensuring optimal energy transmission and enabling a single-pass procedure for improved therapy comfort. To further alleviate standard discomfort of FRMN body treatments, where microneedles are inserted beyond 4 mm, this device employs an 'extended mode', allowing delivery of radiofrequency energy below the needle tip; therefore, the treatment of the subdermal layer without the need for full needle insertion. This pilot investigation aims to assess the therapy comfort of the novel FRMN device, as well as its efficacy and safety.

Materials and Methods

In this prospective, single-center, open-label study, 14 subjects were enrolled (n=14, 13 females, 1 male, 46±17.4 years, skin type I-IV). The objectives were therapy comfort evaluation, safety assessment as well as the efficacy of the treatment, and the subject’s satisfaction with the treatment results. The efficacy was tested on three indications, facial rhytids, acne scars, and body striae. Ten subjects underwent facial treatments, from which five (n=5, 65.6±8.6 years, 4 females and 1 male, skin type I-III) for the treatment of rhytids, and five (n=5, 35±11.6 years, all females, skin type II-IV) for the treatment of acne scars. Four (n=4, 35.3±6.1 years, 3 females, 1 male, skin type I-III) subjects were enrolled for treating abdominal body striae. Subjects were informed about the study procedures before enrollment and signed a written informed consent. Each subject received three single-pass FRMN treatments with the EXION Fractional applicator of the Exion device (BTL Industries, Inc., Boston, MA), spaced 7-14 days apart. Subjects of the facial treatments group had their face treated including cheeks and forehead, and subjects in the body striae group had their abdominal area treated.

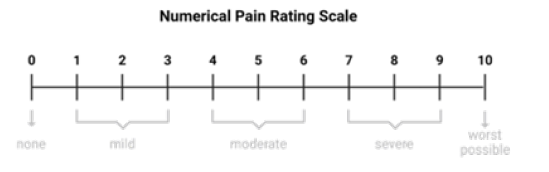

The treated area was free of hair, cleaned from cosmetics and makeup before the therapy, additionally jewelry was removed before the treatments. A topical anesthetic (23% lidocaine, 7% tetracaine, plasticized) was applied to the treatment area and cleaned with 70% alcohol before the start of the treatment. All participants were treated with non-insulated needles. RF energy, and needle depth were set according to the treated area, treatment concern, and the subject’s feedback. Subjects were required to attend all three treatment visits and follow-up visits scheduled at 1 month and 3 months post-treatment. Two-dimensional (2D) photographs of the treated area were taken at baseline, after the last treatment, and at both follow-up visits. The 10-point Numerical Rating Scale for pain (NRS), where 0 represents no pain, and 10 means worst possible pain, was given to subjects after each study treatment to evaluate therapy comfort, see (Figure 1).

The treatment efficacy was assessed using the Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) by three independent evaluators using the 2D photographs. Photographs from after the last treatment and both follow-up visits were compared to baseline photographs, and each evaluator assigned a score to the photograph from -1 to 3 (-1= worse, 0=no change, 1=improved, 2=much improved, 3=very much improved). An improvement was considered when there was an increase in the score. The Friedman test was used to evaluate the statistical significance (α=0.05) of aesthetic improvement using GAIS scores. A 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree) Subject Satisfaction Questionnaire was given to subjects to fill in after the last treatment and at both follow-up visits consisting of the following questions: “I found the treatment comfortable”, “The appearance of the treated area has been improved after the treatments”, “I am satisfied with the treatment results”, “I would undergo the treatments again”. Observation for any adverse events took place during the whole course of the study.

Results and Discussion

All subjects completed all scheduled treatments and the 1-month follow-up visit. Two subjects of rhytid treatments were lost to follow-up at 3 months, therefore only 12 subjects were included in the 3-month analysis, while all 14 subjects were included in the after-treatment and 1-month analysis. No adverse events were observed throughout the study. The radiofrequency energy for facial treatments was set at 40% intensity and inserted needle depth was 1-2mm. Participants with body striae had radiofrequency set to 100% intensity and with a needle depth of 3mm, except for initial treatment of one subject, where the needle depth was set to 1,5mm. The extended mode was turned on during the body treatments. The Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NRS) evaluation revealed an average score of 3.7/10 across all three treatments. The NRS score remained relatively stable throughout the study, with a score of 3.9/10 after the 1st treatment, 3.5/10 after the 2nd treatment, and 3.8/10 after the 3rd treatment. There was a statistically significant improvement in appearance after the facial (p-value <0.0001) and body treatments (p-value 0.0003). The GAIS scores gradually increased, with a peak at 3 months post-treatment. The average aesthetic improvement compared to baseline was 1.7 points for facial treatments and 1.9 points for striae treatments. Although not among the objectives of this study, during photograph evaluation of body treatments, an additional slimming effect was observed. For more details see (Figures 2-5).

Figure 2: GAIS scoring-Facial treatments on the right, body treatments on the left. Tx=treatment, 1M=1-month follow-up, 3M=3-month followup.

Figure 3: Rhytids reduction: Left-baseline photograph, Right-1-month follow-up photograph illustrating the tightening effect, reduction of rhytids and skin texture enhancement. Subject reported high satisfaction (on average 4.6 out of 5 points) in the 5-point Likert scale Subject Satisfaction Questionnaire.

Figure 4: Acne scar reduction: Right-baseline photograph, Left-3-month follow-up visit photograph with a visible reduction of acne scars, and improved skin depressions. The subject was highly satisfied with the study treatment results (5 points out of 5).

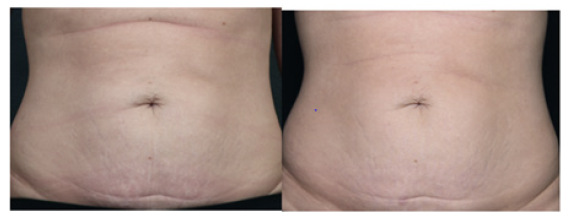

Figure 5: Improvement of body striae, left-baseline, right-3-months post-treatment with an improvement of abdominal striae, noticeable skin tightening. The subject self-reported an appearance improvement in the treated area.

Overall, 97% of all subjects reported an aesthetic improvement in the treated area (mean satisfaction across 1-month and 3-month time points). Initially, at the one-month mark, 90% of facial treatment subjects expressed satisfaction with the outcomes and an improvement in appearance. By the three-month follow-up, satisfaction increased to 100%, underscoring the progression over time. Participants of the body treatments reported consistent satisfaction levels, registering at 100% across both the one-month and three-month follow-up assessments. Most of the subjects (79%) found the treatment comfortable according to the Subject Satisfaction Questionnaire and 11 out of twelve subjects (92%) of subjects reported they would undergo the treatments again. This study aimed to investigate the therapy comfort of the FRMN procedure using the novel device, as well as its safety, and efficacy for treating rhytids, acne scars, and body striae. The NRS assessment revealed an average score of 3.7/10. The treatment efficacy was demonstrated through increased GAIS scores and high patient satisfaction, while its safety was confirmed by the absence of any adverse events. The traditional FRMN procedures can be quite painful, with reported pain levels reaching as high as 8.81 out of 10 [16]. The FRMN treatment using the novel device is in comparison more comfortable, with the mean NRS score of 3.7/10. The Subject Satisfaction Questionnaire revealed that 79% of participants rated the treatment as comfortable, furthermore implying a tolerable level of perceived discomfort. This sentiment is supported by the fact that all participants completed their scheduled treatment sessions, and additionally, 92% expressed willingness to undergo the treatments again. The observed post-treatment appearance change was highly significant on both body (p-value 0.0003) and facial skin (p-value<0.0001), with gradual improvement with every follow-up and the highest GAIS scores obtained at 3 months post-treatment, on average by 1.7 points (body treatments) and 1.9 points (facial treatments). The improvements observed by clinical aestheticians were reflected by study participants as well, all subjects (100%) self-reported an improvement in appearance at the 3-month follow-up visit. The gradual change can be interpreted by the neosynthesis of collagen and elastin. In earlier studies, the effect of FRMN in the human skin tissue has been investigated, with observed increased dermal thickness interpreted by neocollagenesis, neoelastinogenesis, and elevated hyaluronic acid levels [17-19], which has been demonstrated by previous studies to occur even 6 months after the treatments [20]. Restoring dermal volume and elasticity is crucial for improving rhytids, and scars. Increased dermal thickness ultimately leads to the elevation of skin depressions caused by atrophic scars [21], while heightened skin elasticity creates a lifting and tightening effect for reducing rhytids.

The improvement in appearance after body treatments can be attributed to the striae reduction, skin tightening, and abdominal slimming effect. Although the mechanism of the slimming effect should be investigated in future studies, heat-induced adipocyte disruption following RF treatments has been previously demonstrated by several studies [22-24]. With regard to the research methods, some limitations need to be acknowledged. The sample size of 14 subjects represents a limitation of this study and therefore the results cannot be generalized. Future investigations would benefit from a larger sample size, including a wider skin type range, and a higher rate of follow-up visits. Finally, a computed method such as 3D photograph analysis would increase the objectivity of the evaluation. The objectivity was, however, not compromised, as three independent evaluators were assessing the treatment outcome. Despite the limitations, this study also has several strengths, including the investigation of three treatment indications, the use of objective evaluation of treatment results using GAIS by three independent evaluators, and subjective evaluation by the study participants (Table 1).

Conclusion

Study results suggest the Fractional Radiofrequency Microneedling procedure with the novel device is comfortable while sustaining therapy efficacy demonstrated in the treatment of rhytids, acne scars, and body striae.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of Interest

I would like to disclose that I am a consultant for BTL, which provided the study applicator. However, no funding was provided for the clinical investigation, authorship or publication of this article.

References

- (2022) ASPS Procedural Statistics Release.

- (2020) ASPS Plastic Surgery Statistics Report.

- Singh A, Yadav S (2016) Microneedling: Advances and widening horizons. Indian Dermatol Online J 7(4): 244-254.

- Ramaut L, Hoeksema H, Pirayesh A, Stillaert F, Monstrey S (2018) Microneedling: Where do we stand now? A systematic review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 71(1): 1-14.

- M C Aust, K Reimers, H M Kaplan, F Stahl, C Repenning, et al. (2011) Percutaneous collagen induction-regeneration in place of cicatrisation? J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 64(1): 97-107.

- M C Aust, K Reimers, A Gohritz, S Jahn, F Stahl, et al. (2010) Percutaneous collagen induction. Scarless skin rejuvenation: fact or fiction? Clin Exp Dermatol 35(4):437-439.

- Kim MS, Song HJ, Lee SH, Lee CK (2014) Comparative study of various growth factors and cytokines on type I collagen and hyaluronan production in human dermal fibroblasts. J Cosmet Dermatol 13(1): 44-51.

- Andreia Regina Bonjorno, Tatiana Bertacin Gomes, Marli Crisitna Pereira, Camila Miranda de Carvalho, Marilisa Carneiro Leão Gabardo, et al. (2020) Radiofrequency therapy in esthetic dermatology: A review of clinical evidences. J Cosmet Dermatol 19(2): 278-281.

- Weiner SF (2019) Radiofrequency Microneedling: Overview of Technology, Advantages, Differences in Devices, Studies, and Indications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 27(3): 291-303.

- Syder NC, Chen A, Elbuluk N (2023) Radiofrequency and Radiofrequency Microneedling in Skin of Color: A Review of Usage, Safety, and Efficacy. Dermatol Surg 49(5): 489-493.

- Lee SJ, Kim JI, Yang YJ, Nam JH, Kim WS (2015) Treatment of Periorbital Wrinkles With a Novel Fractional Radiofrequency Microneedle System in Dark-Skinned Patients. Dermatol Surg 41(5): 615-622.

- Oltulu P, Ince B, Kokbudak N, Findik S, Kilinc F, et al. (2018) Measurement of Epidermis, Dermis, and Total Skin Thicknesses from Six Different Body Regions with a New Ethical Histometric Technique. Turk J Plast Surg 26(2): 56.

- Karan Chopra, Daniel Calva, Michael Sosin, Kashyap Komarraju Tadisina, Abhishake Banda, et al. (2015) A Comprehensive Examination of Topographic Thickness of Skin in the Human Face. Aesthet Surg J 35(8): 1007-1013.

- Gill HS, Denson DD, Burris BA, Prausnitz MR (2008) Effect of Microneedle Design on Pain in Human Volunteers. Clin J Pain 24(7): 585-594.

- Fruhstorfer H, Schmelzeisen Redeker G, Weiss T (1999) Capillary blood sampling: relation between lancet diameter, lancing pain and blood volume. Eur J Pain 3(3): 283-286.

- Emam AAM, Nada HA, Atwa MA, Tawfik NZ (2022) Split-face comparative study of fractional Er:YAG laser versus microneedling radiofrequency in treatment of atrophic acne scars, using optical coherence tomography for assessment. J Cosmet Dermatol 21(1): 227-236.

- Hantash BM, Ubeid AA, Chang H, Kafi R, Renton B (2009) Bipolar fractional radiofrequency treatment induces neoelastogenesis and neocollagenesis. Lasers Surg Med 41(1): 1-9.

- Seo KY, Yoon MS, Kim DH, Lee HJ (2012) Skin rejuvenation by microneedle fractional radiofrequency treatment in Asian skin; Clinical and histological analysis. Lasers Surg Med 44(8): 631-636.

- Nada HA, Sallam MA, Mohamed MN, Elsaie ML (2021) Optical Coherence Tomography-Assisted Evaluation of Fractional Er:YAG Laser Versus Fractional Microneedling Radiofrequency in Treating Striae Alba. Lasers Surg Med 53(6): 798-805.

- Tan MG, Jo CE, Chapas A, Khetarpal S, Dover JS (2021) Radiofrequency Microneedling: A Comprehensive and Critical Review. Dermatol Surg 47(6): 755-761.

- Orentreich DS, Orentreich N (1995) Subcutaneous incisionless (subcision) surgery for the correction of depressed scars and wrinkles. Dermatol Surg 21(6): 543-549.

- Boisnic S, Divaris M, Nelson AA, Gharavi NM, Lask GP (2014) A clinical and biological evaluation of a novel, noninvasive radiofrequency device for the long-term reduction of adipose tissue. Lasers Surg Med 46(2): 94-103.

- Ana Luísa Vale, Ana Sofia Pereira, Andreia Morais, Andreia Noites, Adriana Clemente Mendonça, et al. (2018) Effects of radiofrequency on adipose tissue: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Cosmet Dermatol 17(5): 703-711.

- Franco W, Kothare A, Ronan SJ, Grekin RC, McCalmont TH (2010) Hyperthermic injury to adipocyte cells by selective heating of subcutaneous fat with a novel radiofrequency device: feasibility studies. Lasers Surg Med 42(5): 361-370.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.