Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Oral Cholera Vaccine Acceptability in the Biyem-Assi Health District: A Cross-Sectional Analytical Study in Yaoundé-Cameroon

*Corresponding author: Edwige Omona Guissana, Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, The University of Yaoundé I, Yaoundé, Cameroon.

Received: November 14, 2024; Published: November 26, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.24.003264

Abstract

Background: Cholera is a global public health threat, particularly in the Centre Region of Cameroon. This study aim was to investigate the determinants of oral cholera vaccine acceptability in the population of the Biyem-Assi Health District; a site of recurrent cholera epidemic.

Methods: A mixed cross-sectional study was conducted from 26 to 27 November 2022 in the Biyem-Assi Health District. Residents aged at least 21 years with informed consent living in the Akok-Ndoé and Simbock Health Areas (HA) were considered eligible. Quantitative data were analyzed using MS Excel 2016 and IBM SPSS 26. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Logistic regression was used to identify determinants of vaccine acceptability and qualitative data were processed by content analysis.

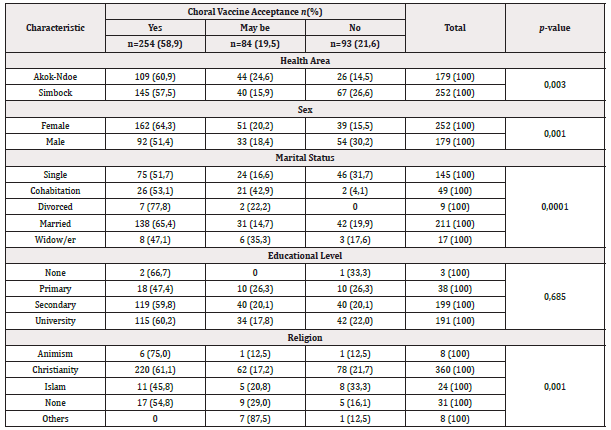

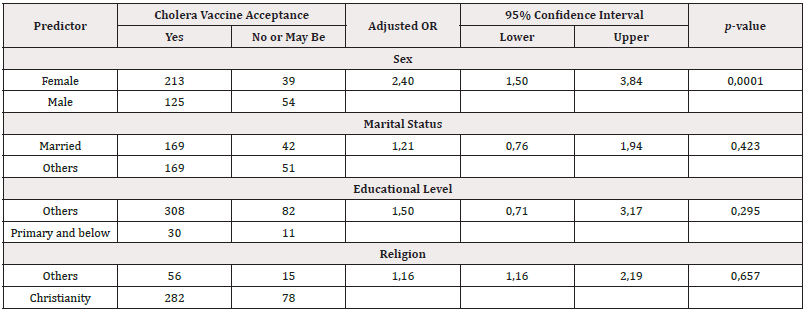

Results: Four hundred and thirty-one people were interviewed in households. The median age of the participants was 32 years. Women represented 58.2% of the respondents. Only 58.9% (p=0.003) of respondents stated they would take the vaccine if it were offered to them. Health area of residence (p=0.003), sex of respondent (p=0.001), marital status (p=0.0001) and religion (p=0.001) were significantly associated with vaccine acceptability. Women were significantly 2.4 times more likely to accept the vaccine than men (CI:1.50-3.84, p=0.0001). To improve vaccine acceptability, continuous community outreaches was suggested by respondents.

Conclusion: To improve the acceptability of the oral cholera vaccine health authorities should organize community awareness campaigns on the efficacy and safety of the vaccine, targeting men as a priority group.

Keywords: Vaccine acceptance, Cholera, Community Awareness, Cameroon

Background

Cholera remains a global threat in public health and it is an indicator of lack of equity and inadequate social development [1]. According to estimates by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), there are between 1.3 and 4 million cases of cholera each year, with between 21,000 and 143,000 deaths worldwide [2]. The first case of Cholera in Cameroon was detected in 1971. Since 1990, major epidemics have been recorded, notably in 1991, 1996, 1998, 2004, 2010 and 2011. The general trend shows an annual increase in the number of cases. Between 2004 and 2016, epidemiological surveillance reported 50,007 cases with 2,052 deaths, giving a high case-fatality rate of 4.1% [3]. As of 2019, outbreaks of cholera have been recorded in several Regions of the country including the Centre, Littoral, Extreme North, North, South-West, East and South Regions [4-6]. As of 31 January 2019, 967 cases, including 23 deaths, had been recorded, representing a case-fatality rate of 2.9% [7]. As of 01 March 2022, the epidemiological profile was as follows: 24 Health Districts (HDs) affected and 18 HDs active. One thousand eight hundred and ninety-eight (1,898) cases have been notified, 76 cases confirmed by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and 55 deaths recorded, for a case-fatality rate of 2.96% [5]. The weeks from the 4th to 18th of March 2022 were marked by the notification of new cases in the Centre region, particularly in the HDs of Mfou, Efoulan, Soa, Monatélé, Nkoldongo and Biyem-assi [8].

Cholera, like other diarrheal diseases, is mainly transmitted via the fecal-oral route. Better access to sanitation services and quality water, as well as appropriate personal hygiene for the population, would reduce morbidity due to diarrheal diseases [9]. As recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2010, Cameroon’s 2018 national cholera response plan proposed 12 main complementary strategies, including mass vaccination of vulnerable and most-at-risk populations [10]. This plan was implemented in April, August and September 2022 among the population aged over one in the Centre, Littoral, South and South-West Regions [11]. However, vaccine hesitancy within households remains an obstacle to optimal vaccination coverage. Although this is a long-standing problem, it has become increasingly important in recent years, and was exacerbated by the COVID-19 epidemic in 2021 [12-14]. It compromises the achievement of the objectives set in the fight against epidemics. Identifying the factors associated with acceptability or reluctance to vaccinate against cholera is therefore of vital importance in preventing and controlling this epidemic, particularly in the communities which are most at risk. Hence, we carried out this study whose aim was to describe the determinants of acceptability of the cholera vaccine among households in the Biyem-Assi health district and to identify their proposals for improving vaccination coverage.

Methodology

This was a mixed, cross-sectional study with descriptive and analytical aims carried out in the Biyem-Assi Health District, which is one of the 32 Districts in the Centre Region of Cameroon. Data were collected from 26 to 27 November 2022 from households in the Akok-Ndoé and Simbock health areas. The Akok-Ndoé health area was selected because it had recorded the most cases of cholera as of 04 July 2022, i.e. 23 out of the 80 recorded in the Biyem-Assi Health District, for an attack rate of 6.4 per 10,000 inhabitants. However, the Simbock health area was one of the health areas that took part in round 1 of the 3rd phase of the vaccination campaign, which ran from 28 September to 02 October 2022. Within households, the questionnaire was administered to the head of the household or any other person aged at least 21 who was present at the time of the survey and had given informed consent to participate. Data collection was carried out by trained community health workers from the Biyem-Assi Health District. Administrative and ethical authorizations were obtained prior to the field work. The minimum sample size defined by the Cochrane formula was 384 households. To distribute the number of households between the different areas, we divided the sample size proportionately between the two health areas using the following formula:

We thus obtained a minimum size of 164 households in the Akok-Ndoé health area for 26,763 inhabitants and a minimum of 220 households in the Simbock health area for 36,025 inhabitants. Systematic sampling was used to select the households to be surveyed. The sampling increment observed was 2. The direction taken was determined using a pen thrown in the air from a central point in the neighborhood represented by the ‘Bon Secours’ pharmacy in the Akok-Ndoé health area and the ‘Les Merveilles’ health center in the Simbock health area (pen method). Data from the quantitative survey were recorded and processed and analyzed using IBM SPSS version 26. A multiple binomial logistic regression was used to identify the socio-demographic determinants of vaccine acceptability, and adjusted Odds Ratios were used to establish the strength of the association between the variables and to eliminate potential confounding factors. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant, and confidence intervals were estimated at the 95% confidence level. Qualitative data were collected from all participants during semi-structured interviews with free and focused responses, using an interview guide coupled with the questionnaire. The processing of these data using the content analysis technique enabled us to highlight the perception of the cholera vaccine and its acceptability in the community.

Results

Socio-Demographic Profile of Participants

A total of 431 participants were interviewed during the course of the study, 252(58.5%) in the Simbock health area and 179(41.5%) in the Akok-Ndoe health area. Participants’ ages ranged from 21 to 74 years, with a median age of 32years. Half of the participants were aged between 26 and 40. More than half of the respondents were women (58.2%). Workers in the private sector were the most represented (51.3%). Nearly half of the participants were married (49%). Nine out of 10 participants (90.5%) had at least secondary education. The majority of respondents (83.5%) were Christians (Table 1). Nearly two out of 10 participants (17.6%) earned less than the minimum wage (SMIC). Two out of 10 participants (19.3%) had a monthly income of between 50,000 and 99,999 FCFA.

Knowledge and Practices Relating to Cholera Prevention

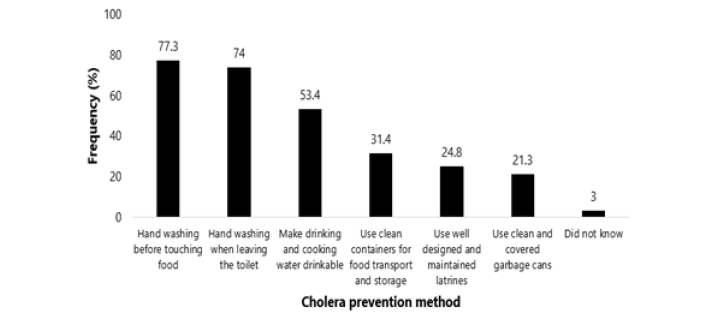

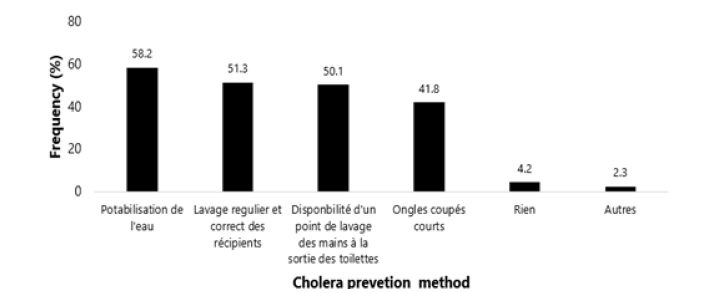

Nearly all participants (95.6%) had already heard of cholera. The most frequently cited information channels were the media (radio and television) (77%), social networks (54%) and posters/ leaflets (32%). Participants identified contaminated or dirty water as the main source of cholera transmission (86.3%), followed by contaminated food (63.3%), dirty hands (58.5%) and poorly maintained toilets (58.2%). A significant proportion of participants had no idea how the disease was transmitted (2.1%). However, more than two-thirds of respondents identified hand-washing before touching food (77.3%), hand-washing after leaving the toilet (74%) and just over half identified drinking water purification (53.4%) as the main recommended means of preventing cholera. A small proportion (3%) of participants had no knowledge of any means of prevention (Figure 1). As means of preventing cholera in households, participants mentioned making drinking water potable (58.2%), regular and correct washing of containers (51.3%) and the availability of hand-washing facilities on leaving the toilet (50.1%) (Figure 2).

Table 1: Acceptability of the Oral Cholera Vaccine according to Socio-demographic Characteristics of in the Biyem-Assi Health District Residents, Central Region, Cameroon, November 2022 (n=431)

Figure 1: Awareness of Cholera Preventing Methods Among Biyem-Assi Health District Residents, Central Region, Cameroon, November 2022 (n=431).

Figure 2: Reported Cholera Preventing Methods Applied in Biyem-Assi Health District Households, Central Region, Cameroon, November 2022 (n=431).

Household Acceptability of the Cholera Vaccine

More than three quarters (77%) of respondents were aware of the importance of cholera vaccination, but only half (58.9%) said they would take the cholera vaccine if it were offered to them. Health area of residence (p=0.003), sex of respondent (p-value=0.001), marital status (p=0.0001) and religion (p=0.001) were significantly associated with acceptance of the cholera vaccine. In this study, women were significantly 2.4 times more likely to accept the cholera vaccine than men (CI:1.50-3.84, p=0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2: Multiple Binomial Logistic Regression of Factors associated with acceptability of the Oral Cholera Vaccine in the Biyem-Assi Health District, Central Region, Cameroon, November 2022 (n=431).

Nearly 75% (134/179) of the people who did not totally accept the cholera vaccine justified their refusal by the lack of certainty about the quality and reliability of the vaccine, and 22.4% (39/179) of them said they could accept it if the vaccine proved to be safe and effective, especially if a community leader or someone close to them took it before them as a safety test. However, some people who were reluctant to be vaccinated (3.3%) said they only wanted to rely on other control and prevention measures and avoid vaccination, while 32% gave no reason for their refusal. To improve the acceptability of the cholera vaccine, the majority of participants (94%) suggested raising public awareness on a continuous basis, with a detailed presentation of the vaccine’s active ingredient and excipients, its efficacy and potential side-effects, using television and radio spots, posters and community workshops.

Discussion

The appropriation or acceptance of a new health action or strategy by a community or population goes through a fairly complex behavioral process which ranges from knowledge of the service offered to its actual use, via approval of its effectiveness and the intention to use it. So, according to the acceptance model for a technology, in this case a vaccine, as described in 1989 the intention to use, which is also acceptability, is based on the ability of the vaccine to be easy to use and have certified benefit to users [15]. The successful integration of the cholera vaccine into the “one-two punch” and “barrier” strategies for responding to this epidemic, as recommended by the national cholera response plan, should be based on data on the acceptability of this strategy among the populations most exposed to cholera. Most of respondents were female, similar findings were obtained in Iraq and Somalia [16,17]. However, in this survey, women were the most likely to accept cholera vaccination, irrespective of their socio-economic level or religious affiliation. This may be justified by the fact that, in our context, women are primarily the ones who are most called upon to provide care and emotional and affective support to the family in the event of illness; as a result, if an effective means of disease prevention exists, they will be more inclined to accept it than men, in order to preserve the emotional and psychological integrity of their family and their own. However, in a patriarchal socio-cultural environment, any decision to have a family member undergo curative or preventive health care, such as vaccination, falls preferentially on men.

Most of participants (77%) felt that vaccination as an additional means of combating cholera was important. Our findings corroborate observations made in the Hoima District of Uganda during a study of household perceptions of the cholera vaccination campaign in 2020 [18]. However, this positive perception of vaccination was contrary to their subjective desire to accept vaccination if it were offered to them. The lack of information on efficacy and the existence or absence of adverse/secondary reactions to the vaccine was the main causes of hesitation and refusal to get vaccinate. Similar barriers were observed in 2021 with the vaccination against COVID-19 and in order to improve vaccination coverage, community and religious leaders and community health workers were mobilized through community engagement meetings to combat misinformation by going door-to-door for sensitization and broadcasting key messages on community radios [19]. In addition, patients who had recovered from COVID-19 and people who had already been vaccinated were invited to testify about the existence and severity of the disease and the safety of the vaccination [14,20]. Respondents’ place of residence was significantly related to vaccine acceptability. Our observation corroborates result in Iraq during mass vaccination in refugee camps. The areas with the highest coverage were those where administrative representatives and health staff had been most involved in the campaign [17]. In order to improve the acceptability of the cholera vaccine and, by extension, vaccination coverage, the study population’s proposal was to disseminate key messages through continuous awareness-raising and outreach. Messages on the various methods of preventing cholera, case management, and the safety and efficacy of the cholera vaccine should be communicated to the population through community radio stations, television channels, information, education and communication workshops on cholera, and posters. This communication strategy for social and behavioral change in the context of vaccination has already been successful in several countries (United States, Somalia, etc.) and for several other vaccines in addition to the cholera vaccine [21].

Conclusion

The fight against cholera is based on a range of strategies, including vaccination. However, public acceptance of cholera vaccination, particularly in the most affected Health Districts, remains a challenge in Cameroon. Some determinants of the cholera vaccine acceptability were identified within the community including gender, marital status and level of information. Upscaling continuous community awareness on the efficacy and safety of this vaccine is one of the levers that can be used to improve vaccination coverage and achieve herd immunity against cholera.

Limitations

As the study only took place in one health district in the Centre region, its conclusions can only be applied to other districts with a similar socio-economic and cultural context.

Declaration

Author’s Contribution

a) Conception: Edwige Omona Guissana, Florence Kissougle Nkongo, Franck Metomb, Hervé Stan Mbida, Charlotte Moussi Omgba.

b) Data Analysis and Interpretation: Edwige Omona Guissana, Fabrice Zobel Lekeumo Cheuyem. Drafting of the original manuscript: Edwige Omona Guissana.

c) Correction of Manuscript: Edwige Omona Guissana, Florence Kissougle Nkongo, Franck Metomb, Fabrice Zobel Lekeumo Cheuyem, Ariane Nouko Hervé Stan Mbida, Tatiana Mossus-Etounou, Charlotte Moussi Omgba.

d) Approval of Final Version of Manuscript: All authors.

Funding Source

None.

Ethical Approval Statement

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Regional Human Health Committee of the Centre (CRERSH-Ce) and the ethical clearance: CE N°1403/CRERSHC/2022 issued.

Acknowledgements

Our gratitude goes to the Services of the Regional Delegation of Public Health for the Centre Region (Brigade of Control of Healthcare Activities and the Regional Unit of Prevention and Control of Epidemics, Pandemics and Disasters) and the Biyem-Assi Health District for their availability during the implementation of activities in the field. We address our gratitude to the community health workers in the Biyem-Assi health district for their contributions during data collection.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Benicourt E (2001) Poverty according to the UNDP and the World Bank. Rural Studies 35-54.

- (2020) Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). Cholera PAHO/WHO.

- (2022) World Health Organization (WHO). Outbreak Newsletter; Cholera-Republic of Cameroon

- (2019) Cameroon: Situation of the Cholera epidemic in the North and Far North regions (10/10/2019)-Cameroon | Relief Web.

- (2022) Public Health Emergency Operations Coordination Centre. Cholera Situation Report Cameroon N°

- (2021) Public Health Emergency Operations Coordination Centre. Cholera Situation Report No.1.

- (2023) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Cameroon Situation Report. [Internet]. Bamenda.

- (2022) CERPLE-CE. Cholera investigation report in the Biyem-Assi Health District. Centre Region: Centre Regional Delegation for Public Health.

- (2019) Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS). Safer water, better health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- (2018) National Cholera Outbreak Response Plan in Cameroon, August-October 2018-Cameroon | ReliefWeb.

- (2022) Data Cameroon. Cholera: 5 days to inoculate 366,320 doses of vaccine in Cameroon. Data Cameroon.

- Amani A, Ngo Bama S, Dia M, Nguefack Lekelem S, Linjouom A, Mossi Makembe H, et al. (2022) Challenges, best practices, and lessons learned from oral cholera mass vaccination campaign in urban Cameroon during the COVID-19 era. Vaccine 40: 6873-6879.

- Amani A, Cheuyem Lekeumo F, Asaah Tatang C, Mbang M, Epee Douba E, et al. (2022) Challenges and Lessons Learnt after Two Mass Campaigns of Oral Cholera Vaccine in Hard-to-Reach Fishermen Communities. Health Sci Dis 23(5).

- Amani A, Mossus T, Lekeumo Cheuyem FZ, Bilounga C, Mikamb P, Basseguin Atchou J, et al. (2022) Gender and COVID-19 Vaccine Disparities in Cameroon. COVID 2(12): 1715-1730.

- Martin NPY (2018) Acceptability, Acceptance, and User Experience: Evaluating and Modeling Technology Product Adoption Factors. HAL open science 259.

- Lubogo M, Mohamed AM, Ali AH, Ali AH, Popal GR, Kiongo D, et al. (2020) Oral cholera vaccination coverage in an acute emergency setting in Somalia, 2017. Vaccine 38: A141-A147.

- Lam E, Al Tamimi W, Russell SP, Butt MOI, Blanton C, Musani AS, et al. (2017) Oral Cholera Vaccine Coverage during an Outbreak and Humanitarian Crisis, Iraq, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 23(1): 38-45.

- Bwire G, Roskosky M, Ballard A, Brooks WA, Okello A, Rafael F, et al. (2020) Use of surveys to evaluate an integrated oral cholera vaccine campaign in response to a cholera outbreak in Hoima district, Uganda. BMJ Open 10: e038464.

- Nalova Akua (2022) How Cameroon is gradually overcoming vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines Work.

- (2021) World Health Organization. In Cameroon, community leaders are driving demand for COVID-19 vaccines. WHO | Regional Office for Africa.

- Kirkwood J, Wilson MK (2021) Social and behaviour change communication campaigns to reduce vaccine hesitancy. CARE 2021.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.