Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Relationship of the Cardiac Fulcrum and the AV Node with Ventricular Torsion

*Corresponding author: Trainini Jorge, Hospital Presidente Perón, Buenos Aires, Argentina. National University of Avellaneda, Argentina.

Received: September 30, 2024; Published: October 04, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.24.003180

Abstract

Objective: The heart operates through three fundamental units: activation, electromechanical and torsion, which are interrelated in their anatomy and organization.

Methods: Anatomical, histological and histochemical studies were carried out on 35 hearts from the morgue and slaughterhouses (18 bovine, 16 humans, 1 pig). In five patients, the endo-and epicardial electrical activation sequence of the left ventricle was investigated using three-dimensional electro anatomical mapping.

Results: The AV node is located at the atrio-ventricular junction, at the base of the muscular septum, below the birth of the great vessels. It is adjacent to the cardiac support (fulcrum), located between it and the implantation of the septal valve of the tricuspid. The finding of the research is that the neurofilaments of the nodule penetrate the interior of the cardiac fulcrum. Myocardial torsion is produced by the transfer between the descending and ascending segments. The activation spreads from the endocardium to the epicardium, that is, from the descending to the ascending, generating opposing forces. From this point, the ascending segment depolarizes in a double direction: towards the tip and towards the base, while the descending segment completes its activation towards the apex.

Conclusions: The mechanical consequence of the cardiac structure is the beginning of stimulation in the anatomofunctional unit between the AV node and the cardiac fulcrum, and its conti

Keywords: Cardiac support, AV node, Myocardial torsion

Introduction

There is always a step in nature where functions superior to those known can be integrated with the members that make up a system [1-5]. The heart was historically analyzed in its participatory components with a global and homogeneous contraction, but not in the understanding that the movements in its different phases occur sequentially and superimposed, contributing to its function in a complex way with a time of less than one second per cycle. Through the development of technology applied to cardiac morphology, a comprehensive biological perspective adapted to the functional requirement was achieved.

Previous publications [6-8] corresponding to the cardiac fulcrum (myocardial support), its relationship with the Aschoff- Tawara node and the sequential activation of the heart in clear organizational disposition to torsional movement [9-15], led us to analyze these structures in the potentiality and the functional aspects it has [16-19]. In this way we arrive at the concept that the heart acts through three fundamental units: activation, electromechanical and torsión.

Material and Methods

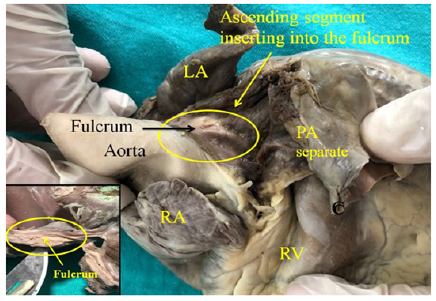

Research on Cardiac Fulcrum and AV Node

In anatomical and histological research, bovine, pig and human hearts have been used. Thirty-five hearts from the morgue and slaughterhouse were used: a) 18 bovine (adults); b) 16 human ( embryos, infants, adults);1 pig. Anatomical, histological and histochemical studies were carried out. The heart was fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and histology was performed using hematoxylin-eosin and Masson’s trichrome staining technique in four-micron sections. Ten percent formalin was used as buffer and immunohistochemistry staining (s100-neurofilaments) was also implemented [20]. The single continuous and helical myocardium was deployed according to a previously technique (Figure 1) [1,9]. The conjunction of birth with the end of the continuous and intact cardiac muscle, on a support, has been called cardiac fulcrum [1,17], constitutes a meeting point that allows the heart to adopt in space an arrangement of a set of fibers twisted on themselves, like a laterally flattened rope with the formation of a double helicoid that delimits the two ventricular cavities. Samples were taken from the cardiac fulcrum in its relationship with the AV node (Figure 1).

Activation of the Myocardium

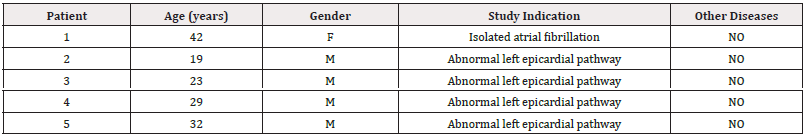

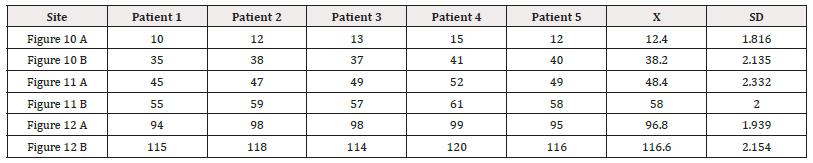

The endo and epicardial electrical activation sequence of the left ventricle has been studied by means of three-dimensional electroanatomic mapping (3D-EAM) with a Carto navigation and mapping system that allows a three-dimensional anatomical representation, with activation maps and electrical propagation. The study included patients who provided their informed consent. The research was previously approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. All patients were in sinus rhythm, with a normal QRS and did not have evident structural heart disease by Doppler echocardiography and in gamma camera studies (Table 1).

3D-EAM was performed during radiofrequency ablation for arrhythmias owing to probable abnormal occult epicardial pathways. The presence of abnormal pathways did not interfere with mapping, as during the whole procedure baseline sinus rhythm was preserved with normal QRS complexes. As the muscular structure of the left ventricle is made up of an endocardial layer (descending segment) and an epicardial layer (left and ascending segments), two approaches were used to carry out mapping. The endocardial access was performed through a conventional atrial transseptal puncture. The epicardial access was obtained by means of a percutaneous approach in the pericardial cavity with an ablation catheter. The propagation times were measured in milliseconds(ms).

Results

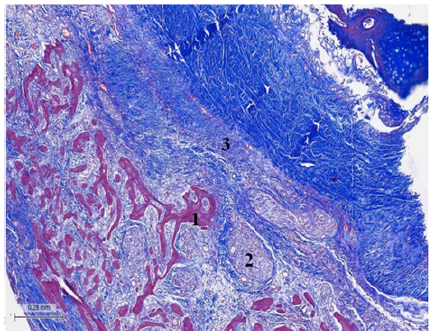

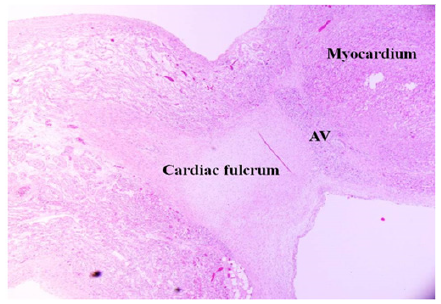

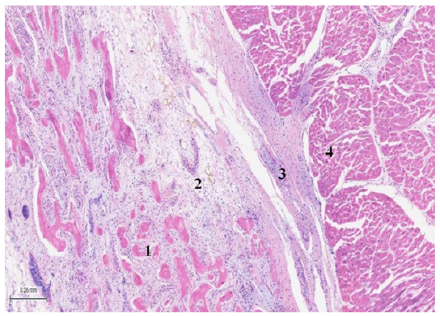

The fulcrum, because of the location in the atrioventricular junction, below the aorta and the pulmonary artery, is adjacent to the AV node, which is situated at its right (Figures 2-5). The important finding originating from both macroscopic and microscopic observations reveal the attachment of myocardial fibers to this nucleus. Its configuration has been histologically confirmed, being its osteo-chondroid-tendinous structure according to the specimens analyzed. In bovids, its size is approximately 37mm long, 45mm wide and 15mm thick, being triangular. In humans, it has the same shape, its size being 50% in each of its dimensions [1,9,17] (Figure 3-5).

Figure 2: Adult human heart. The ascending segment can be seen inserting into the cardiac fulcrum. LA: Left Atrium; RA: Right Atrium; PA: Pulmonary Artery; RV: Right Ventricle. The right inset shows the fulcrum.

Figure 3: (Bovine heart). Masson’s trichrome technique. 25x. Tangential section of the fulcrum. Fulcrum osseous trabeculae including plexuses with neurofilaments. 1. Osseous tissue. 2. Terminal plexuses. 3. Fibroconnective tissue.

Figure 4: 36-day newborn human heart. Magnification 20x. The fulcrum with cartilaginous matrix is seen with the myocardium and the adjacent Atrioventricular Node (AV).

Figure 5: (Bovine heart), H&E (25x). The image shows plexuses associated with fibro-chondroid trabeculae and the myocardium. 1: bone trabeculae. 2: plexuses. 3: fibroconnective tissue. 4: myocardium.

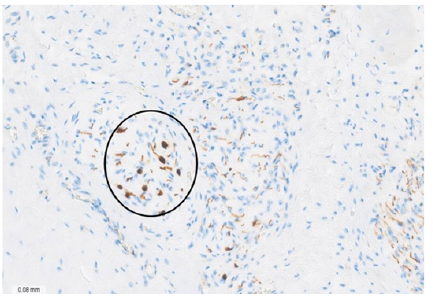

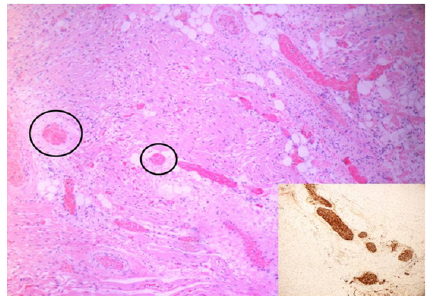

The AV node is adjacent to the cardiac fulcrum, between it and the implantation of the tricuspid valve septal leaflet. It is a cluster of cells (specialized myocytes) that Rushmer defines as a spherical or bulbous end consisting of bundles of fibers [21] to transmit the electrical impulses to the myocardial mass, starting at the fulcrum. The histological showed that the cardiac fulcrum is adjacent to the AV node, forming a rich cellular cluster of plexuses with neurofilaments (Figures 6,7). The fundamental finding of this investigation is that the neurofilaments (Figure 8) are also inside the cardiac fulcrum.

The adjacency between the cardiac fulcrum and the beginning of the continuous myocardium, in relation to the AV node, demonstrated that stimulation in the right ventricular outflow tract for pacemaker placement was more effective [9]. The AV node allows the output activation to be modified in response to an input activation to control the pause within the cardiac cycle. It is no coincidence that the AV node is adjacent to the cardiac fulcrum. Repressive transcriptional factors are mainly responsible for maintaining the phenotype of the cardiac conduction system, since, in their absence, the precursor cell develops into a working cardiomyocyte [22]. Through the use of immunohistochemistry methods aimed at identifying the expression of the protein connexin 43 (Cx 43), which is part of the intercellular signaling in cardiac conduction, two continuous structures were described in the AV node with a different pattern: one, without expression of Cx43, located to the left and in the compact zone of the AV node and another with Cx43 expression to the right and in the area called the inferior nodal bundle. It is important to emphasize that this molecular and histochemical compartmentalization is not apparent in histology. It is further proposed that the Cx43–region characterizes the fast conduction compartment, while the Cx43+region is expressed in the slow conduction compartment.

Figure 7: Bovine heart. Immunohistochemistry staining technique for neurofilaments 50x. The encircled area shows axons and ganglion cells. The chondroid tissue in the upper right region corresponds to the fulcrum.

Figure 8: 27-week infant heart. The image shows nervous trunk hypertrophy in the fulcrum (black circles) adjacent to the AV node, HEx200. The inset illustrates the thick nervous trunk in the fulcrum confirmed by immunohistochemistry for S-100.

Cardiac Activation

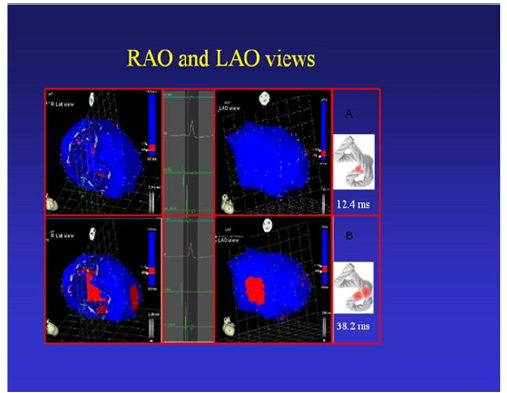

As 3D-EAM corresponded to the left ventricle, the activation wave previously generated in the right ventricle was not obtained. Remember that the descending band is made up of the right, left and descending segments, while the ascending band is made up of only the ascending segment (Figure 9-12). Figures 10 to 12 show the propagation of endocardial an epicardial electrical activation. In all the figures the right projection is observed in the left panel and the simultaneous left anterior oblique projection in the right panel. At each time, the activated zones are detailed in red. The lateral inset represents the activation of the descending and ascending muscle bands that make up the ventricular continuous structure of the myocardium in the cord model.

Figure 9: Cord model of the helical myocardium. It illustrates the different segments forming this structure. In blue: Basal loop. In red: Apical loop. PA. Pulmonary Artery; A: Aorta.

Figure 10: Onset of left ventricular activation. The left panel shows the depolarization of the interventricular septum, corresponding to the descending band. In the right panel, the ventricular epicardium (ascending band), has not been activated yet. B. Simultaneous band activation. Activation progresses in the left ventricular septum through the descending band (longitudinal activation) and simultaneously propagates to the epicardium (transverse activation) activating the ascending band.

Figure 11: A. Bidirectional apex and ascending band activation. The final activation of the septum is observed, progressing towards the apex, synchronously with the epicardial activation in the same direction. At the same time the epicardial activation is directed towards the base of the left ventricle. B. Activation Progression. Activation progresses in the same directions of the previous figure.

Figure 12: Late activation of the ascending band. At this moment, which corresponds to approximately 60% of QRS duration, the endocavitary activation (descending band) is already complete. The distal portion of the ascending (epicardial) band depolarizes later. This phenomenon correlates with the persistence of the band contraction in the initial phase of diastole. B. Final Activation. In the right panel, the projection was changed from left anterior oblique to left posterolateral, showing very late activation of the distal portion of the ascending band.

In all figures, the area depolarized at that time is represented in red and those that were previously activated and are in refractory period are represented in blue. Below the cord model, the average electrical propagation time along the myocardium can be seen measured in Milliseconds(ms) at the analyzed site (Table 2 and 3).

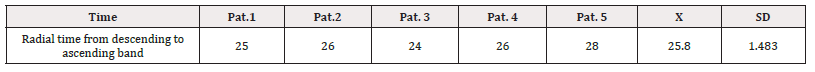

Left ventricular activation occurs 12.4ms±1.816ms after the onset in the interventricular septum (Figure 10 A). Based on the anatomy that these fibers occupy, the endocardium is the first area of the left ventricle to receive electromechanical activation. At that moment it also propagates to an epicardial area-ascending band-evidencing a transverse activation at a point we call “band crossover” which is produced 25.8±1.483ms after stimulation of the ascending segment (Figure 10 B, Table 3) and at 38.2±2.135ms from the onset of cardiac activation (Figure 10, Table 2). This results in opposite rotations between the ventricular base (counterclockwise rotation) and the apex (clockwise rotation). This probably occurs at the level where the subendocardial fibers of the descending segment, on the anterior surface of the left ventricle, run deep through the mesocardium, crossing obliquely with those of the ascending segment, thus facilitating transverse stimulation between both segments.

References. ms: Milliseconds; Pat: Patient; X: Mean; SD: Standard Deviation.

In echocardiographic studies greater systolic torsion was found in the mid-interventricular septum than in the anterior walls [23]. Synchronously, following the anatomical arrangement of the descending band, the activation propagates longitudinally towards the ventricular apex, reaching it at 58±2.0ms (Figures 11 A and B, Table 2).

From “band crossover” onwards the activation loses its unidirectional character and becomes slightly more complex. Three simultaneous wave fronts are generated: 1) the distal activation of the descending band towards the apical loop; 2) the depolarization of the ascending band from band crossover towards the apex and 3) the activation of this band from the crossover point towards its final portion in its insertion in the cardiac fulcrum, myocardial support. Figures 11 B, 12 A and B shows the continuation and completion of this process. Intracavitary activation ends long before QRS termination (Figure 12 A). The rest of the QRS corresponds to the late activation of the distal portion of the ascending band, which justifies the persistence of its contraction during the isovolumic diastolic phase. This contraction constitutes the basis of the ventricular suction mechanism (Figure 12 B), and for this reason, it will be now termed Protodiastolic Phase of Myocardial Contraction (PPMC), as in it there is contraction and no relaxation. A synthesis of the stimulation found in this study is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13: Cord model. Activation sequence (A-F) in the myocardium according to our investigation, with propagation times. The 25.8 milliseconds in B is the stimulation delay to go from the descending band in A to the ascending band in B. References. In red: depolarization; in blue: already activated zones.

Discussion

In the research we find an organizational pattern that makes cardiac functioning. They are: 1) the anatomical contiguity between the AV node and the cardiac fulcrum; 2) the presence in continuity of the filaments that structure the AV node inside the fulcrum-where the myocardium begins- in a clear interpretation of forming an electromechanical unit and 3) the path of activation through the myocardium that allows helical torsión/detorsion, through the anatomical, anisotropic and functional situation between the descending and ascending segments at the septal level. Function leads the myocardium to have a supporting point as any skeletal muscle. If it did not have this anatomical spatial helical configuration, if it did not have an insertion at its ends located at the base of the heart (cardiac fulcrum) and did not remain free in the apex, that is, pendant in the thorax, and also if it did not present a stimulation allowing its torsion and detorsion, it would be unable to function with its extraordinary muscular power. The adjacency of the cardiac fulcrum to the AV node, surrounded by a rich plexus of neurofilaments, that penetrate inside the fulcrum, leads us to consider an electromechanical unit, in which the stimulation energy and muscle mechanics participate [10]. This electromechanical unit between the AV node and the myocardial support obtains its mechanical continuity with the interpretation of the stimulation path, which allows explaining the helix movement with the corresponding myocardial torsion.

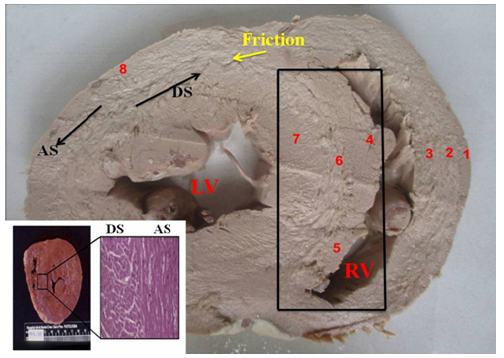

The helical myocardial arrangement forces the muscle to overlap segments in its spatial configuration [24]. At the upper end of its path the ascending segment runs isolated to be tied to the fulcrum. A fundamental subject with no electrophysiological evidence, was to consider ventricular filling as an active phenomenon generated by myocardial contraction that tends to lengthen the left ventricular apex-base distance after the ejective phase, producing a suction effect (“suction cup”). This mechanism is explained by the persistent contraction of the ascending segment during the onset of the PPMC. The final part of the QRS corresponds in our investigation to the activation of the ascending segment. With the onset of detorsion occurring during this phase, the ascending segment progressively lengthens, generating negative intraventricular pressure with this segment still contracted, an energy residue of the torsion process [12]. A transverse section of the heart (Figure 14), below the atrioventricular valves, shows that the descending segment is inner and surrounded by the ascending segment in the left ventricular free wall [1]. The ascending and descending segments undergo opposite movements, both in systole and diastole, to achieve the expulsion and suction of the ventricular blood content, generating friction between their surfaces. The hyaluronic acid, which has a lubricating function, is abundant in both in the myocardium and the Thebesius vessels [19]. The histology in Figures 14 and 15 clearly shows the different orientation of the fibers of the descending segment in relation to the ascending one, which explains the opposite movements that they present. The arrangement of the myocardial fibers in the epicardium and endocardium, whose change in angulation of 180° causes the epicardial fibers to be arranged in the opposite orientation to the endocardial fibers. Given the different anisotropic orientations of the fibers, this area corresponds to the beginning of the opposite movement of the descending and ascending segments that produces myocardial torsion. Figure 15 shows in a model the constitution of the septum and the contiguity between the descending and ascending segments.

Figure 14: Transverse section of the heart (Human). 1. Interband fibers; 2. Right paraepicardial bundle; 3. Right paraendocardial bundle; 4. Anterior septal band; 5. Posterior septal band; 6. Intraseptal band; 7 Descending segment; 8. Ascending segment; LV: Left Ventricle; RV: Right Ventricle. The black arrows indicate the course of movement in each segment during systole. The yellow arrow indicates the friction plane between the segments; AS: left-handed ascending segment; DS: right-handed descending segment. The box indicates the septum with the different segments that make it up. Lower angle: microscopic view (right) of the interventricular septum medial segment in the human heart, clearly showing absence of transition circumferential fibers between the descending (right) and ascending (left) segments of the myocardium. In the macroscopic (left), it can be seen how the sudden transition of the fiber angle change draws a line that can be perceived.

Figure 15: Constitution of the septum. Ref. 1: anterior septal band (dependent on the right segment). 2: ascending segment. 3: descending segment. 4: posterior septal band (dependent on the right segment). Black circle: the anatomical contiguity between the descending and ascending segments, which is confirmed with the histology in the lower box, which shows the different orientation of the longitudinal fibers (Ascending Segment, (SA) in relation to the descending one (transverse fibers, SD).

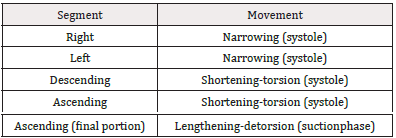

Fiber orientation in the continuous myocardium and their activation implies a sequence of muscle movements, giving rise to four phases: narrowing, shortening-torsion, lengthening-detorsion and expansion, allowing the functions of systole, suction and diastole (Table 4).

This sequential activation correlates with fundamental phenomena that are well known today, such as the opposing clockwise and counterclockwise torsion of the apex and base of the left ventricle, responsible for its mechanical efficiency (Figure 10). The concepts developed by Armour [25] reached greater agreement with the anatomical situation of both ventricles, since in the integral arrangement of the loops, the basal one embraces the apex, which determines that the right ventricular cavity is rather an open slit in the thickness of the muscles that make up both ventricles (Figure 16, upper corner).

Figure 16: Helical myocardium in the rope model. Shows the different segments that make it up. In blue: basal loop. In red: apical loop; PA: Pulmonary Artery; A: Aorta; r: energy receiver; e: energy emission. The three anatomofunctional units that allow the integration between the AV node, the cardiac fulcrum and myocardial torsion are detailed. The black circle details the site that we have called the crossing of the bands. Given the different anisotropic orientations of the fibers, this area corresponds to the beginning of the opposite helical movement that produces myocardial torsion. In the upper corner the spatial arrangement of the continuous helical myocardium is observed.

In this shell the stimulation goes from subepicardium to subendocardium. Then, it stimulates the descending segment and at the average 25.8ms in our research the ascending segment is activated. The completion of the stimulation in the myocardium occurs at the level of the terminal part of the ascending segment, close to inserting into the cardiac fulcrum, during the first 80-100ms of diastole in the period traditionally known as the diastolic isovolumetric phase and which we have called PPMC. Since Harvey and later with Einthoven’s electrocardiography, the electrical activation and the mechanical contraction of the heart were homogeneous processes. In this way, the contraction would occur “en bloc” during systole and the relaxation would occur homogeneously during diastole. At this point of current knowledge of the helical myocardium, these concepts do not explain cardiac function. Figures 10 to 12 allow explaining the activation sequence of the contractile areas and their entry into cardiac dynamics in relation to the pathway of the excitation wave, with a coordinated pattern according to the helical structure of the myocardium. The investigation performed with 3D-EAM explains the torsion phase of the heart, defined as the opposite rotational movement of the base and the apex. Activation, for this purpose, at the crossing point of the descending and ascending segments propagates from the endocardium to the epicardium (transvers propagation), that is, from the descending to the ascending segment. The ventricular narrowing phase (isovolumic systole) at the beginning of systole is produced by the contraction of the basal loop right and left segments. The shortening phase is owing to the descent of the base at the same time as myocardial torsion, and originates longitudinally, as the annulus contracts before the apex. The fact that the apex does not move is due to the movement of the base, descending in systole and ascending in diastole. Although there is a progression in electrical conduction along the continuous myocardium, this one-way activation does not explain the generation of a force capable of ejecting ventricular contents at a speed of 200cm/s at low energy. In this way, the propagation from the descending segment to the ascending segment plays a fundamental role in ventricular torsion, by allowing opposing forces on its longitudinal axis to generate the intraventricular pressure necessary to achieve sudden blood expulsion. In this way, a twisting mechanism like “wringing a towel” would be produced, as described by Lower in 1669 [9].

Conclusions

During this research, in all hearts, it was found in the histological study that the fulcrum is adjacent to the AV node, determining a space rich in plexuses with neurofilaments. A fundamental finding is that neurofilaments also occupy the cardiac fulcrum. We have mapped the activation of the left ventricle on its endocavitary and epicardial surfaces. The mechanical consequence of the cardiac structure is the beginning of stimulation in the anatomofunctional unit between the AV node and the cardiac fulcrum, and its continuity in myocardial activation to the zone of almost simultaneous activation between the descending and ascending segments, which generates torsion of the myocardium, due to opposite rotation between the base and the apex with simultaneous shortening of both ventricles. This entire process involves the necessary arrangement of intraventricular pressures for the functioning of the heart valves in the circulatory cycle. In this way, it is understood that the functioning (Figure 16) of the myocardium obeys three interrelated units of its organization, namely: 1) activation unit (AV node); 2) electromechanical unit (cardiac fulcrum) and 3) torsion/detorsion unit. With this interpretation, it is about seeing the pattern of organization of the heart and not simply making fragments with its knowledge (Figure 16).

Funding

None declared.

Authors’ Contributions

Jorge Trainini: Research Coordination

Mario. Beraudo: Anatomy

Mario Wernicke: Histology

Alejandro Trainini: Anatomy

Marta Cohen: Histology

Benjamín Elencwajg: Electrophysiology

Oscar Fariña: Cardiac mechanic

Jesús Valle Cabezas: Cardiac mechanic

María Elena Bastarrica: Cardiology

Diego Lowenstein Haber: Images

Francesc Carreras Costa: Images

Vicente Mora Llabata: Images

Jorge Lowenstein: Images

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Trainini JC, Lowenstein JA, Beraudo M, Mora Llabata V, Carreras Costa F Cabezas Valle J, et al. (2022) “Fulcrum and Torsion of the Helical Myocardium”. Editorial Biblos, Buenos Aires.

- Ballester-Rodés M, Flotats A, Torrent-Guasp F, Carrió-Gasset I, Ballester-Alomar M, et al. (2006) The sequence of regional ventricular motion. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 29(Suppl 1): 139-144.

- Ballester M, Ferreira A, Carreras F (2008) The myocardial band. Heart Fail Clin 4(3): 261-272.

- Carreras F, Garcia-Barnes J, Gil D, Pujadas S, Li CH, et al. (2012) Left ventricular torsion and longitudinal shortening: two fundamental components of myocardial mechanics assessed by tagged cine-MRI in normal subjects. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 28(2): 273-284.

- Hayabuchi Y, Sakata M, Kagami S (2015) Assessment of the helical ventricular myocardial band using standard echocardiography. Echocardiography 32(2): 310-318.

- Bateson G (1979) Mind and nature: a necessary unity. Dutton, New York.

- Bertalanffy von L (1978) Teoría general de los sistemas. Alianza, Buenos Aires.

- Gorelik G (1975) Principal Ideas of Bogdanov’s Tektology: The Universal Science of Organization. General Systems 20: 3-13.

- Trainini J, Lowenstein J, Beraudo M, Valle Cabezas J, Wernicke M, et al. (2023) Anatomy and Organization of the Helical Heart. UNDAV Ed, Buenos Aires; Argentina.

- Trainini J, Wernicke M , Beraudo M , Cohen M, TraininiI A, et al (2023) Cardiac Fulcrum, its Relationship with the Atrioventricular Node. Rev Argent Cardiol 91: 449-455.

- Trainini J, Beraudo M, Wernicke M, Lowenstein J, Carreras-Costa F, et al. (2021) “Physiology of the Helical Heart”. Int J Anat Appl Physiol 7(5):195-204.

- Trainini JC, Elencwajg B, López Cabanillas N, Herreros J, Lago N, et al. (2015) Electrical Propagation in the Mechanisms of Torsion and Suction in a Three-phase. Rev Argent Cardiol 83(5): 416-28.

- Trainini JC, Elencwajg B, López-Cabanillas N, Herreros J, Lago N (2015) Electrophysiological Basis of Torsión and Suction in the Continuous Cardiac Band Model. Anat Physiol 5: S4-001.

- Trainini JC, Elencwajg B, López-Cabanillas N, Herreros J, Lago N (2015) Ventricular torsion and cardiac suction effect. The electrophysiological analysis of the cardiac muscle”. J Clin Exp Cardiolog 6: 10.

- Trainini JC, Elencwajg B, Herreros J (2017) New Physiological Concept of the Heart. Ann Transplant Res 1(1): 1001.

- Trainini JC, Elencwajg B , López Cabanillas N, Herreros J, Lago N, et al. (2018) Stimulus Propagation and Left Ventricular Torsion. Advancements in Cardiovascular Research 1(2): 31-36.

- Trainini J, Lowenstein J, Beraudo M, Wernicke M, Trainini A, et al. (2021) Myocardial torsion and cardiac fulcrum (Torsion myocardique et pivot cardiaque) . Morphologie 105(348): 15-23.

- Trainini JC, Beraudo M, Wernicke M, Carreras Costa F, Trainini A, et al. (2022) Evidence that the myocardium is a continuous helical muscle with one insertion. REC: CardioClinics 57: 194-202.

- Trainini J, Beraudo M, Wernicke M, Carreras Costa F, Trainini A, et al. (2022) The hyaluronic acid in intramyocardial sliding. REC: CardioClinics.

- Gourdie RG, Mima T, Thompson RP, Mikawa T (1995) Terminal diversification of the myocyte lineage generates Purkinje fibers of the cardiac conduction system. Development 121(5): 1423-1431.

- Rushmer RF, Crystal DK, Wagner C (1953) The functional anatomy of ventricular contraction. Circ Res 1(2): 162-170.

- Christoffels VM, Burch JBE, Moorman AFM (2004) Architectural plan for the heart: early patterning and delineation of the chambers and the nodes. Trends Cardiovasc Med 14(8): 301-307.

- Mora Llabata V, Roldán Torresa I, Saurí Ortiza A, Fernández Galera R, Monteagudo Viana M, et al. (2016) Correspondence of myocardial strain with Torrent-Guasp’ s theory. Contributions of new echocardiographic parameters. Rev Arg de Cardiol 84(6): 541-549.

- Valle J, Herreros J, Trainini J, García Jimenez E, Talents M, et al. (2017) Three-dimensional definition of Torrent Guasp´s ventricular muscle band and its correlation with electric activation of the left ventricle (abstract). XXIII Congreso SEIQ, Madrid, España, BJS 105(2).

- Armour JA, Randall WC (1970) Structural basis for cardiac function. Am J Physiol 218(6): 1517-1523.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.