Case Report

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

The Clinical Outcome of Our Case of Vaginal Cuff Dehisence

*Corresponding author: Ibrahim Polat, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cam and Sakura City Hospital, Turkey.

Received: October 28, 2024; Published: November 12, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.24.003239

Abstract

Vaginal Cuff Dehisence is an extremly rare and potenitally mortal compication that occurs following a total hysterectomy. Due to it’s rare occurance, the prevention, diagnosis and optimal management is not clear. The following is a case presentation of a 45-year-old female who presented with a vaginal cuff dehisence following a total laparoscopic hysterecomy and biateral salpingectomy. Risk factors regarding the patient are discussed along with the diagnosis and succesful treatment of the defect. By sharing this case we aim to increase knowlege on the subject and build a platform for the discussion of this rare complication.

Keywords: Vaginal dehiscence, Vaginal cuff closure, Laparoscopy, Evisceration, Risk factors

Introduction

Vaginal cuff dehiscence (VCD) is an extremely rare and serious complication that can occur after a total hysterectomy. The complication maybe a partial or complete dehiscence of the vaginal cuff. Furthermore, the prolapse of intraperitoneal organs through the defect can complicate the condition. Due to the potential of small bowel ischemia, peritonitis, and sepsis, it requires urgent diagnosis and surgical treatment. Although the etiology is not clear, various risk factors may be attributed. It has been reported that the incidence is higher in cases of robotic hysterectomy and total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) compared to vaginal and abdominal hysterectomies [1]. As robotic or laparoscopic hysterectomies increase, VCD cases may become more frequent in the future. Sharing information regarding risk factors present in these patients, preventive measures that may be taken, surgical techniques, and patient management may contribute to an increase in knowledge of these complications in litrature. Due to how rare this complication is, both diagnosis and optimal treatment maybe delayed. Our aim is to highlight this condition by presenting this very rare case, thereby raising awareness for early diagnosis and emergent surgical intervention to prevent morbidity and mortality. We believe that the comparison of different surgical techniques to prevent VCD, especially in robotic or laparoscopic hysterectomy, will only be possible with the publication of institutional data. Research and sharing on preventive measures for VCD and the optimal surgical management of this complication should be encouraged.

Case Presentation

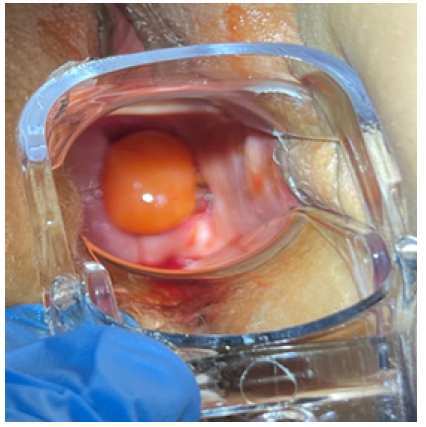

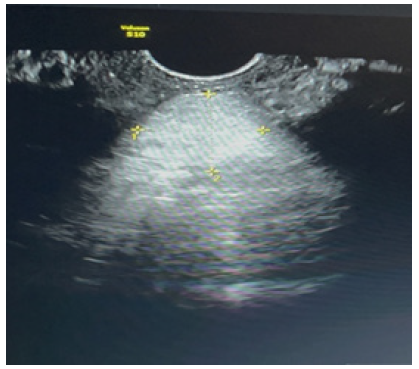

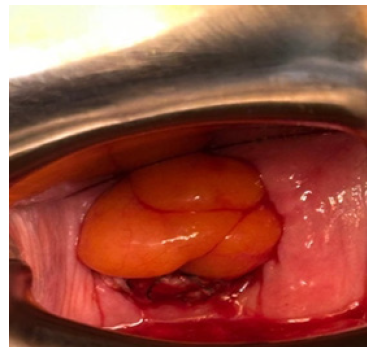

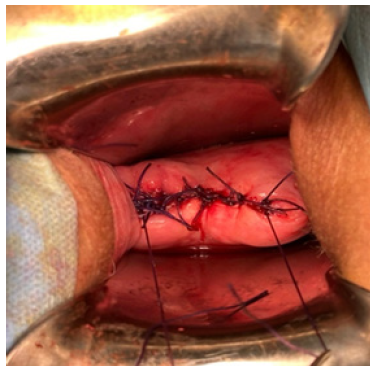

A.S, a 45-year-old woman, has a history of two vaginal deliveries and a Transobturator Tape (TOT) procedure performed 10 years ago for urinary incontinence; she has no other illnesses, allergies, or history of medication use; her body mass index is 27, and she smokes 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day. The patient underwent TLH (Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy) and Bilateral Salpingectomy due to abnormal uterine bleeding, with preoperative pathology tests revealing benign results. During the operation, the vaginal cuff was circumferentially cut from front to back using a monopolar hook, and the vaginal cuff was sutured with 2.0 V-loc. Postoperative follow-ups were uneventful. 1.5 months after the operation, she presented to the gynecology clinic with complaints of bloody vaginal discharge, a sensation of pressure towards the vagina, and lower abdominal pain following coitus. On speculum examination, a 3x3 cm prolapsed mass from the vaginal cuff and minimal vaginal bleeding was observed (Figure 1). Vital signs were stable, together with an unremarkable abdominal examination. Her bowel sounds were also found to be normoactive on auscultation. Vaginal ultrasonography showed a solid mass above the cuff, with no evidence of bowel prolapse (Figure 2). Laboratory tests, including hemogram and biochemical studies, were normal. The patient was thus admitted to emergency surgery for transvaginal cuff repair due to suspicion of vaginal cuff dehiscence and omental prolapse. Peroperatively, the omentum was reduced back into the abdomen via vajinal route in trandelenberg position (Figure 3). Upon further examination the vaginal cuff was found to be partially necrotic. Single interrupted sutures with 0 Vicryl were placed in a 4cm long dehisced cuff (Figure 4). No issues were detected during the 1st week and 2nd-month postoperative follow-up.

Discussion

Hysterectomy is the most frequently performed procedure among gynecological surgeries [2]. In our clinic, 1,838 hysterectomies were performed over a 10-year period from 2014 to 2024, during which 3 cases of vaginal cuff dehiscence (VCD) requiring surgical correction were observed. The definition of VCD can range from partial opening of the vaginal cuff to the prolapse of abdominal contents into the vagina [3]. The most severe scenario is the prolapse of the small intestine into the vagina, which is a condition requiring urgent surgery due to the risk of acute small bowel ischemia, peritonitis, and sepsis. The definition and incidence of VCD vary from study to study. In literature, the incidence of vaginal cuff dehiscence is reported to range between 0.14% and 4.1% [4,5]. This rate is 0.16% in our clinic.

Risk factors for VCD include advanced age, vaginal atrophy, the presence of malignancy that delays wound healing, smoking, corticosteroid use, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, prior radiation therapy to the tissue, the presence of a vaginal cuff hematoma or infection, increased Valsalva maneuvers (such as chronic coughing), and engaging in coitus before healing is complete [5,6,7,8]. In our hospital, all three cases occurred in the premenopausal period. Our patient had a history of smoking and engaged in sexual activity 1.5 months after surgery. It is recommended to avoid vaginal intercourse for at least 2 months postoperatively [9]. However it is important to ntoe that up to 70% of VCD cases occur spontaneously without any risk factors [10].

Vaginal cuff dehiscence (VCD) is more commonly observed after robotic hysterectomy or total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) compared to vaginal or abdominal hysterectomies. In a study, the incidence rates of VCD after laparoscopic (n=2853), vaginal (n=4150), and abdominal (n=5538) hysterectomies were reported as 0.11%, 0.05%, and 0.02%, respectively. The VCD rate after TLH was found to be five times higher compared to total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) and twice as high compared to vaginal hysterectomy [1]. In our clinic, TLH constitutes 39% (722/1838) of all hysterectomies, with a VCD rate of 0.4% after TLH. All three cases observed in our hospital occurred after TLH. In the first case, bowel evisceration was observed, while omental evisceration occurred in the other two cases.

As minimally invasive hysterectomy advanced techniques, it is important to investigate the reasons for the potential increase in VCD incidence. For the increased VCD incidence after TLH, factors such as laparoscopic suture technique, suture type, limited tissue margin during cuff repair, knots, suture materials, and particularly the use of monopolar electrosurgery have been considered to be risk factors. Intensive coagulation to achieve hemostasis in the vaginal cuff is thought to cause cellular necrosis and tissue damage. When comparing TLH cases with electrosurgery to other hysterectomy cases without electrosurgery, the incidence of VCD was higher in the TLH group; however, no postoperative hematoma or infection cases were observed before VCD. This suggests that electrosurgery might result in better hemostasis. Therefore further research is needed to determine whether electrosurgery adversely affects tissue healing and scar formation [10]. Studies have been conducted comparing different suture techniques for closing the vaginal cuff. A two-layer continuous suture technique was found to be safer and more effective compared to the figure-eight suture technique, however no statistically significant advantage was observed regarding VCD [11]. Another study demonstrated that using bidirectional barbed sutures reduced the risk of VCD [12]. In this study it is believed that taking thicker tissue during vaginal cuff closure may increase the potential benefit rather than the suture technique itself. The degree to which these suture techniques affect the incidence of dehiscence is unclear [10]. Laparoscopic versus transvaginal closure of the vaginal cuff at the end of TLH has been compared, and it has been shown that laparoscopic closure is associated with a significant reduction in vaginal dehiscence, vaginal bleeding, vaginal cuff hematoma, postoperative infection, need for vaginal re-suturing, and reoperation [9].

In the three VCD cases observed in our clinic, the vaginal cuff was circumferentially cut from front to back using a monopolar hook. In the first case, the vaginal cuff was left open and not sutured. In the last two cases, the vaginal cuff was sutured laparoscopically with 2.0 V-loc. All three surgeries were performed by different well experienced surgeons. We do not know how much healthy tissue the surgeons took during cuff closure. We also do not have information about the risk factors in the cases other than ours.

Vaginal cuff dehiscence (VCD) can occur at any time after a hysterectomy. Litreture reports cases occurring from 3 days to 30 years postoperatively8. Repair methods for VCD can include transvaginal, transabdominal, laparoscopic, or combined approaches. The method of repair is influenced by factors such as the patient's stability, the level of suspicion of intra-abdominal organ damage, whether bowel evisceration is present, assessment of bowel viability, the surgeon's experience, and the ability to visualize the vaginal opening. However, in cases of bowel prolapse, an examination of the bowel is necessary to determine if bowel resection and anastomosis are required. In our clinic, one of the three cases was repaired laparoscopically, while the other two were repaired vaginally. In our case, a transvaginal approach was used. The patient had natural bowel functions on clinical and ultrasonographic examination. We observed less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay, lower costs, and faster recovery in our patient. Although the vaginal approach is minimally invasive, in cases where the vaginal cuff cannot be accessed or when observation and intervention on intra-abdominal organs are required laparoscopic or intra-abdominal approach maybe preferred. In cases of bowel prolapse, laparoscopic repair may reduce the risk of bowel injury during surgery compared to vaginal repair. It has been reported that 51% of VCD cases are repaired transvaginally, 32% transabdominally, 2% laparoscopically, and 5% are left to heal by secondary intention [10].

Conclusion

Laparoscopic techniques in hysterectomy are more advantageous compared to abdominal hysterectomy. With the increasing preference for robotic or laparoscopic hysterectomy today, VCD cases are expected to become more frequent. Much of the literature on VCD comes from case reports. Given that VCD is a rare complication, publishing data on VCD from institutions could facilitate comparisons of different surgical techniques and patient management. Documenting these complications will support the increase and sharing of knowledge in litrature. For our case, we have clear information on risk factors, surgical methods, and repair techniques. However, for our other cases, we lack information on risk factors specific to the patients beyond the surgical methods used. The variability among surgeons and our lack of information on how much healthy tissue was taken during TLH cuff suturing are gaps in our clinical data. VCD is a serious complication of hysterectomy, therefore research and sharing on its prevention and optimal management should continue.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Ala-Nissilä S, Laurikainen E, Mäkinen J, Jokimaa V (2019) Vaginal cuff dehiscence is observed in a higher rate after total laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with other types of hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 98(1): 44-50.

- Garry R (2005) Health economics of hysterectomy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 19(3): 45.

- Hur H-C, Lightfoot M, Gomez M, McMillin MG, Kho KA (2016) Vaginal cuff dehiscence and evisceration: a review of the literature. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 28: 297-303.

- Hur HC, Donnellan N, Mansuria S, Barber RE, Guido R, Lee T (2011) Vaginal cuff dehiscence after different modes of hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 118(4): 794-801.

- Kho RM, Akl MN, Cornella JL, Magtibay PM, Wechter ME, et al. (2009) Incidence and characteristics of patients with vaginal cuff dehiscence after robotic procedures. Obstet Gynecol 114: 231-235.

- Riaz A, Thomas F, Catrin S, Ginimol Mathew, Ahmed Kerwan (2020) The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int J Surg 84: 226-230.

- Serafim PR, Ribeiro RJ, Omar F (2010) Spontaneous transvaginal small bowel evisceration: A case report. Clinics 65(5): 559-561.

- Cardosi R J, M S Hoffman, W S Roberts, W N Spellacy (1999) Vaginal evisceration after hysterectomy in premenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol 94(5 Pt 2): 859.

- Uccella S, Malzoni M, Cromi A, Renato Seracchioli, Giuseppe Ciravolo, et al. (2018) Laparoscopic vs transvaginal cuff closure after total laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomized trial by the Italian Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 218(5): 500.e1-e13.

- Cronin B, Sung VW, Matteson KA (2012) Vaginal cuff dehiscence: risk factors and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 206(4): 284-288.

- Jeung IC, Baek JM, Park EK, Lee HN, Kim CJ, et al. (2010) A prospective comparison of vaginal stump suturing techniques during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 282(6): 631-638.

- Siedhoff MT, Yunker, Steege JF (2011) Decreased incidence of vaginal cuff dehiscence after laparoscopic closure with bidirectional barbed sutureJ Minim Invasive Gynecol 18(2): 218-223.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.