Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

The Role of Aging on Executive Functions and Episodic Memory: The Moderating Role of Coping Self-efficacy and Social Support in an Elderly Sample

*Corresponding author: Mohammad Hossein Abdollahi, Professor of Cognitive psychology, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

Received: October 28, 2024; Published: November 05, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.24.003228

Abstract

The moderating role of coping self-efficacy and social support in relation to age-related changes in executive functions and episodic memory in older adults was explored. The research employed correlation and moderation analyses. The sample comprised 369 Iranian individuals aged between 60 and 80, selected through convenience sampling. The assessment tools included a cognitive abilities questionnaire [1], an autobiographical memory test [2], a coping self-efficacy scale [3], and a social support scale [4].

The correlation analysis highlighted a significant positive association between coping self-efficacy, social support, and executive functions as well as episodic memory. Social support and coping self-efficacy exhibited the strongest correlation with executive functions. Moderation analysis was conducted to assess the combined impact of age and moderating factors (social support and coping self-efficacy). The findings indicated that social support could moderate the influence of age on certain cognitive abilities and episodic memory, while coping self-efficacy did not show a significant moderating effect. Furthermore, social support was found to mitigate the negative effects of aging on inhibitory control, selective attention, decisionmaking, planning, sustained attention, and episodic memory. These results underscore the importance of leveraging both internal and external resources, particularly social support, in mitigating the adverse effects of cognitive decline in older adults. As such, comprehensive strategies and interventions are recommended for promoting healthy aging and enhancing these valuable resources.

Keywords: Aging, Executive Functions episodic memory, Coping Self-Efficacy, Social support elderly

Introduction

Despite the inevitability of aging, the global elderly population is experiencing significant growth [5]. However, age-related cognitive decline presents an escalating challenge [6]. Cognitive function plays a crucial role in enabling the elderly to maintain a sense of independence by managing finances, adhering to medication schedules, and driving safely [7]. As cognitive abilities naturally diminish with age, addressing cognitive impairment in the elderly has emerged as a pressing healthcare priority [8]. The incidence of brain pathologies, such as cortical atrophy and vascular damage, correlates closely with advancing age [5].

Throughout lifespan, the structure and function of the brain undergo changes. Neuronal firing patterns and the ability to form new memories can be altered by aging. Certain protective factors have the capacity to mitigate the detrimental effects of aging to some degree [9]. Therefore, recognizing and leveraging both internal and external resources that safeguard the elderly from severe age-related cognitive decline is of paramount importance [10]. Older individuals commonly encounter cognitive deterioration, memory deficits, and other alterations in nervous system function [8]. Numerous studies have demonstrated a strong link between poor cognitive health and increased rates of mental health disorders, suicidal tendencies, difficulties in daily functioning, and diminished quality of life [11-13].

Cognitive aging is a crucial aspect of the aging process, significantly impacting various facets of elderly individuals' lives, particularly in their later years. Defined by the Public Health Dimensions Committee as an ongoing process of cognitive function change, cognitive aging affects executive functions and episodic memory as individuals age. Executive functions serve as key cognitive correlates of executive states, representing top-down cognitive processes vital for coordinating fundamental cognitive functions during goal-oriented problem-solving. Furthermore, episodic memory, essential for encoding and retrieving information with context related to time and place, is vital for day-to-day tasks and meaningful social interactions.

While cognitive decline is a natural part of aging, significant variability exists in the cognitive abilities of older adults. Resource Protective Factors (RPFs) play a crucial role in shielding individuals from the negative impacts of stressors, with internal factors like self-efficacy and external factors such as social support contributing to this protective mechanism. Research indicates that internal and external resources can influence cognitive performance in old age. This study investigates coping self-efficacy and social support as internal and external resources, respectively, aimed at alleviating age-related declines in executive functions and episodic memory. Bandura (1977) described coping self-efficacy as the belief in one's capacity to effectively deal with challenges, a widely recognized concept in coping and stress-related research [14]. This construct involves problem-solving, emotional regulation, and leveraging support from one's social network [3]. Numerous studies have explored the correlation between self-efficacy and chronic diseases in older adults [15].

Over recent decades, our comprehension of the impact of stress on cognitive functions and processes has notably advanced. Stress can influence task strategies' recovery and practice effects on cognitive performance, altering cognitive task outcomes [16]. Studies indicate that cortisol levels increase post-stress, resulting in a gradual decline in memory retrieval within 2 to 3 hours [17]. Self-efficacy is associated with various significant traits such as self-esteem, responsibility, goal setting, and commitment to objectives [18]. The concept of self-efficacy, wherein individuals evaluate their competence to achieve tasks within specific domains before carrying them out, is closely linked to memory retention.

Social support is another essential variable that can influence the impact of age on cognitive abilities. Research suggests that environmental factors can contribute to diminished cognitive performance through their influence on social resources [19]. The presence of adequate social resources can act as a buffer against stress, thereby safeguarding individuals' health [20]. Social support stands out as a robust predictor of wellbeing and longevity. Extensive prospective studies have demonstrated that social support significantly influences the health of older individuals, independent of factors like socioeconomic status, health behaviors, healthcare utilization, and personality traits [21]. The concept of social support encompasses both structural and functional dimensions [20]. Structural social support quantitatively measures the extent of an individual's social network, while functional social support qualitatively assesses the strength of interpersonal relationships that are readily available to fulfill one's needs. Studies have indicated that social support plays a crucial role in sustaining cognitive functions, including executive functions and memory [22].

The objective of this study is to explore whether coping self-efficacy and social support, two critical resilience-promoting factors linked to age-related cognitive decline, can moderate the relationship between age and executive function as well as episodic memory among older adults.

Method

Participants

This study included 369 Iranian elderly individuals (aged between 60-84 years; mean age 66.39; SD=5.21; 60.4% male), selected through convenient and purposive sampling methods. Single individuals constituted 0.3% of the sample, 78.9% were married, 7% were divorced, and 13.8% were widowed. The educational distribution of participants was as follows: 4.1% had literacy skills, 7% had elementary education, 9.5% had secondary education, 30.4% held a diploma, 22.8% had an undergraduate degree, 10.8% had a graduate degree, and 15.4% had a PhD. The inclusion criteria consisted of elderly men and women aged between 60 and 85 years residing in Tehran. Participants with a history of acute physical or psychiatric illness were excluded from the study. Prior to their involvement in the research, all participants provided written informed consent. Convenient sampling was utilized, and the absence of acute physical or mental illness were prerequisites for participant inclusion in the study.

Research Design

The present study employs a quantitative methodology in terms of its primary goal and theoretical framework. Initially, the study's objectives were outlined. Subsequently, necessary arrangements were made with the families of elderly individuals who volunteered to participate. By adhering to ethical guidelines and obtaining informed consent, as well as ensuring participant confidentiality, individual assessments were conducted at the convenience of the participants. To prevent participant fatigue, the questionnaires were divided into two parts due to the extensive number of questions. Following the completion of a demographic questionnaire assessing age, marital status, number of children, and education level, four surveys were administered to investigate the main and moderating variables.

Statistical Analyses

Pearson correlation, differential correlation, and moderator analysis were employed to test the research hypotheses. The moderator analysis procedure was conducted utilizing Hayes' process (2017) and the PROCESS Macro plugin in SPSS software (SPSS Inc.). Interactive graphs were utilized to visualize conditional effects.

Assessments

Cognitive Ability Scale: The 30-item questionnaire, comprising 7 components-memory, inhibitory control, selective attention, decision-making, planning, sustained attention, social cognition, and cognitive flexibility-was developed and standardized by Nejati in 2012 [1]. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha method, resulting in an alpha coefficient of 0.834, indicating excellent reliability. Internal consistency values for the subscales were as follows: memory-related questions, 0.755; inhibitory control and selective attention, 0.626; decision-making, 0.612; planning, 0.578; sustained attention, 0.534; social cognition, 0.438; and cognitive flexibility, 0.455. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaire utilized was 0.913 as determined by the Cronbach's alpha coefficient.

Autobiographical Memory Test: This test is designed to assess the memory of the elderly with regard to their history of events, initially introduced by Williams and Broadbent in 1986 [2]. The test involves presenting words with varying emotional connotations. Participants are required to associate each word with a specific event or memory from their past. The event recalled must be distinctive, related to a specific time, place, and duration, and can be significant or trivial, associated with the past or present, or a combination of both, within a timeframe of one day or less. Participants are provided with an example of what constitutes a "specific" event; for instance, if the word is "enjoyment", the response "I usually enjoy parties" is considered non-specific as it lacks references to a particular time or place, while a response like "last Friday at Ali's party" is deemed specific. Initially, Williams and Broadbent allocated 1 minute for each word response, while subsequent studies reduced the time to 30 seconds. Failure to provide a response within the stipulated time is recorded as an "omission". Responses are categorized as "specific" if they meet the specific criteria, and as "non-specific" otherwise. In some studies, various forms of non-specific responses have been distinguished. For example, Williams & Dritschel [23] differentiated between non-specific memories, which are broad generalizations classified as "categorical" memories (e.g., I always fail exams), and extended general memories (e.g., memories from the first semester in university). In this study, both specific and non-specific responses were demonstrated to each participant. Each participant was given 30 seconds to provide their response (memory retrieval). The initial memories recalled were categorized as specific or non-specific. Two assessors conducted this test for all participants. The correlation between the assessors' scores for specific memories ranged from 0.83 to 0.94. Consistent with previous research [24], in instances of no response, non-specific memories were further classified as categorical, extended, or omitted memories. Only the data pertaining to specific memories were examined in this study. The questionnaire demonstrated good internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.750.

Coping Self-Efficacy Questionnaire: The Self-Efficacy Scale, developed by Chesney et al. in 2006 [3], assesses positive and constructive coping strategies and emphasizes an individual's belief in their ability to cope effectively. The scale scores reflect an individual's confidence in their capacity to navigate life's crises and challenges. This self-efficacy questionnaire consists of 26 items and utilizes a 3-point Likert scale. It encompasses three distinct subscales:

1) Managing excitement and negative thoughts.

2) Problem-focused coping; and

3) Seeking support from family and friends.

Chesney, et al. reported reliability coefficients of 0.80, 0.83, and 0.91 for the problem-focused coping, managing negative emotions and thoughts, and seeking support from family and friends’ subscales, respectively. The validity of the scale was confirmed via confirmatory factor analysis, with good fit indices (GFI = 0.91, and RMSEA = 0.05), indicating favorable validity. Morovati, et al. further validated the construct of the questionnaire through a factor analysis test across the three aforementioned subscales.

Hladek, et al. in 2020 [15] reported a high internal reliability of 0.944 for this questionnaire using the Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The internal consistency coefficients, as measured by Cronbach's alpha, were 0.866 for problem-focused coping, 0.901 for managing negative emotions and thoughts, and 0.840 for seeking support from family and friends.

Social Support Questionnaire: The Social Support Scale developed by Cutrona and Russell assesses the perceived level of social support. This scale encompasses six subscales focusing on aspects such as dependence, social cohesion, self-worth, connectivity, growth opportunities and learning, and guidance and advice. The reported reliability for the subscales ranged between 0.65 and 0.76, with an overall scale reliability of 0.92. Zaki conducted a study establishing the construct validity of this scale by correlating it with social satisfaction scales, yielding a validity coefficient of 0.50. The scale demonstrated good reliability with a coefficient of 0.75 in Zaki's study. Additionally, the scale has been utilized in research involving elderly populations, as seen in a study by Wong et al., where the reliability was reported to be 0.951 using the Cronbach's alpha coefficient.

Results

Descriptive Statistic

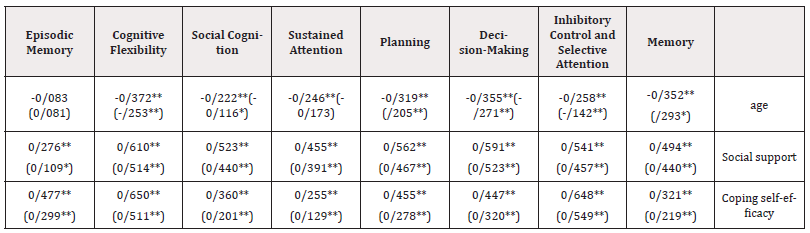

For data analysis, in the descriptive statistics section, statistical indicators of mean, standard deviation and minimum and maximum values were used (Table 1).

Correlations Analyses

In the analysis, it was found that age exhibited a negative correlation with all cognitive abilities, albeit the correlation with episodic memory was not deemed significant. On the other hand, a positive and significant relationship was observed between social support, coping self-efficacy, and all cognitive abilities, including episodic memory. The correlation coefficients were notably high for cognitive flexibility, with social support and coping self-efficacy displaying values of r = 0.610 (P < 0.001) and r = 0.650 (P < 0.001), respectively. Further analysis via differential correlation, controlling for the influence of education, reaffirmed the significant association between social support, coping self-efficacy, cognitive functions, and episodic memory. Notably, a significant relationship was also observed between age and executive functions (Table 2).

Table 2: Pearson Correlation and Differential Correlation (While Controlling for Education Effect) of Age, Social Support, and Self-efficacy With Cognitive Abilities and Episodic Memoryaa * P < 0.05 ** P < 0.01.

Note*: Numbers within parentheses are differential correlation while controlling for the effect of education.

Moderator Analysis

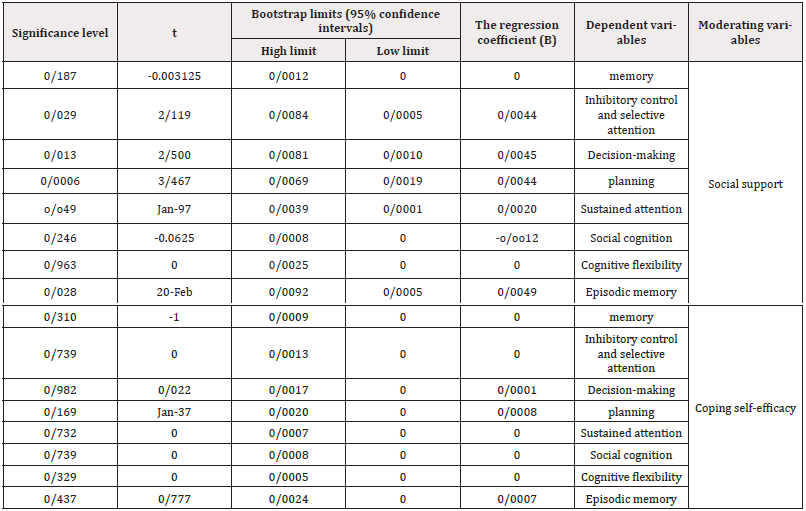

Modulatory analysis was conducted to assess the interactive impact of age with moderating variables, specifically social support and coping self-efficacy. The results highlighted that social support was able to moderate the influence of age on certain aspects of cognitive abilities and episodic memory, whereas coping self-efficacy did not exhibit a significant moderating effect (see Table 2). It was found that social support played a moderating role in age's effect on inhibitory control and selective attention (B = 0.0044, t = 2.19, P = 0.029), decision-making (B = 0.0045, t = 2.50, P = 0.013), planning (B = 0.0044, t = 3.46, P = 0.0006), sustained attention (B = 0.0020, t = 1.97, P = 0.049), and episodic memory (B = 0.0049, t = 2.20, P = 0.028) (Table 3).

Table 3: The Moderating Effect of Social Support and Coping Self-efficacy about Age with Cognitive Abilities and Episodic Memoryaa.

Note*: Bold values indicate significant effects.

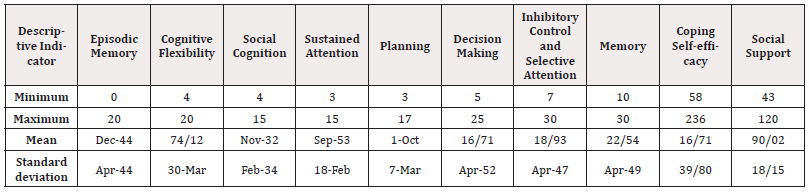

Conditional effect analyses revealed that the impact of age on inhibitory control and selective attention was statistically significant at low social support levels (B = -0.177, t = -3.79, P = 0.0002) and moderate social support levels (B = -0.092, t = -2.25, P = 0.025). However, this effect was not significant at high levels of social support (B = -0.008, t = -0.123, P = 0.902) (refer to Figure 1.A). The age effect on decision-making was significant at low social support levels (B = -0.238, t = -5.70, P = 0.0001) and moderate social support levels (B = -0.152, t = -4.13, P = 0.0001), but not significant at high social support levels (B = -0.065, t = -1.13, P = 0.257) (Figure 1.B).

Further, the analysis demonstrated that the impact of age on the planning component was significant at low social support levels (B = -0.168, t = -5.77, P = 0.0001) and moderate social support levels (B = -0.085, t = -3.29, P = 0.0011), yet it was not significant at high social support levels (B = -0.001, t = -0.024, P = 0.980) (Figure 1.C).

The findings for sustained attention exhibited similar patterns in relation to the impact of age and social support levels.

The influence of age on sustained attention was found to be statistically significant at low social support levels (B = -0.086, t = -3.75, P = 0.0002) and medium levels of social support (B = -0.049, t = -2.40, P = 0.016). However, the effect was not significant at high levels of social support (B = -0.011, t = -0.354, P = 0.723) (Figure 1, D). Overall, these outcomes suggest that increased social support among older individuals reduces the negative impact of age on cognitive functions, with this effect becoming insignificant at high levels of social support.

Additionally, the study revealed that the relationship between age and episodic memory is influenced by social support. Analysis on conditional effects indicated that the effect of age on episodic memory was not significant at low (B = -0.074, t = -1.45, P = 0.147), medium (B = 0.019, t = 0.42, P = 0.673) and high levels of social support (B = 0.112, t = 1.58, P = 0.114). This finding aligns with a previously established non-significant Pearson correlation between age and memory (r = -0.083, P = NS). However, the findings suggest that as social support increases, the relationship between age and episodic memory transitions from negative to positive.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impact of coping self-efficacy and social support, internal and external factors respectively, on mitigating age-related effects on executive functions and episodic memory in a cohort of elderly Iranian individuals. Our findings revealed that, even when adjusting to education levels, age, social support, and coping self-efficacy were significantly associated with cognitive abilities and episodic memory. To assess the interactive effects of age with coping self-efficacy and social support as moderators, a moderator analysis was conducted. The results demonstrated that social support could moderate the influence of age on certain executive functions and episodic memory components, while coping self-efficacy did not exhibit a significant moderating effect on these components. Previous research has consistently reported a notable decline in cognitive performance with advancing age [5,8-10,25-34,35].

Executive functions are critical cognitive processes that are particularly vulnerable to the effects of aging [36]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that executive functions decline as individuals grow older, leading to difficulties in behavioral control and goal achievement [26]. These functions encompass top-down cognitive processes such as inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility, which are crucial for directing behavior towards specific objectives. Additionally, executive functions play a role in actively maintaining problem-specific information in working memory, filtering out irrelevant data, and inhibiting actions that may interfere with task completion. Research underscores the significance of executive functions in self-regulation, everyday tasks, academic performance, and social adaptation, suggesting that deterioration of these cognitive processes can have significant implications for the physical and psychological well-being of older adults [37]. As executive functions are essential for cognitive control processes necessary for independence, adaptive behavior, and goal-directed actions, they serve as reliable indicators of functional decline in later stages of life [36]. Conversely, a growing body of literature indicates that age-related episodic memory decline is a natural and expected aspect of the aging process [38,39].

An important feature of age-related memory decline is that older individuals tend to remember less specific information compared to younger individuals. They are more likely to focus on the overall gist of information when making memory recall decisions [40], which can lead to further declines in memory function with age. Studies utilizing neuroimaging techniques have consistently identified changes in brain activity during memory encoding in older adults, such as reduced activity in regions like the occipital and fusiform sulcus, as well as the medial temporal lobes.

Research suggests that age-related memory impairments may be associated with disruptions in dopaminergic regulation in the hippocampus. Older individuals exhibit increased sensitivity to dopaminergic issues, which could be linked to memory decline stemming from the loss of dopamine neurons and D2-like receptors in the hippocampus. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of moderating factors in preserving cognitive function in old age. Coping self-efficacy and social support are identified as internal and external resources that play a crucial role in mitigating cognitive decline associated with aging and reducing negative outcomes related to cognitive deficiencies in older individuals.

Memories of our experiences are vital for maintaining our sense of self and guiding our daily actions and decisions, promoting flexibility in adapting to changing environments. The susceptibility of episodic memory to age-related declines compared to other forms of long-term memory has been highlighted in various research studies. The article discusses the challenges faced by elderly individuals, who are more likely to encounter acute and chronic stressors over time. It emphasizes the importance of identifying protective factors that can help reduce stress and mitigate its negative consequences on physical and mental health. Research examining the direct and indirect roles of self-efficacy in elderly health highlights the significance of cognitive factors in understanding their adaptive performance.

For nearly four decades, studies have explored the relationship between acute stress and memory. While the cortisol response can predict transitions from goal-directed to behavioral control, the impact of stress itself may not have the same effect. Cortisol's ability to cross the brain-blood barrier intensifies its positive and negative effects on the brain. During the initial stress response phase, cortisol binds strongly with glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors in the amygdala and hippocampus, both critical for memory formation and retrieval. Memory retrieval is typically compromised post-stress, especially when cortisol levels peak for an extended period, longer than 3 hours. The article discusses the impact of coping self-efficacy on psychological distress in response to stressors, drawing insights from studies conducted by Bandura, Reese, Adams, and others. It underscores the importance of coping strategies in facilitating adaptation throughout life, as per Lazarus and Folkman's paradigm, which defines coping as ongoing efforts to manage internal and external circumstances and access personal resources. Coping self-efficacy is shown to enhance psychological well-being, quality of life, and may prevent cognitive decline in older individuals.

Furthermore, the study highlights the moderating role of social support in cognitive functions among elderly individuals. Social support is posited to help maintain stability, self-worth, and effective problem-solving efforts during times of stress, acting as a protective buffer against threats to well-being. Physiologically, social support can moderate cardiovascular reactivity, while psychologically, it aids in boosting self-esteem, mastery, and a sense of competence. Studies suggest that strong social support can shield older individuals from clinical manifestations of pathology, fostering positive psychological outcomes and cognitive function in later life. The article emphasizes the significant protective role of social support in mitigating the adverse effects of aging, especially in the context of cognitive functions and overall well-being [41-58].

The article explores the positive correlation between social support and cognitive functions in the elderly, referencing previous studies by [59] and [60] to support its findings. It indicates that social support has lasting effects on working memory, perceptual speed, and visual-spatial ability, with implications for problem-solving skills and processing efficiency rather than mere information storage [60]. The article also notes that social support is associated with improved health outcomes and reduced mortality rates [30,61]. Various underlying mechanisms contribute to this relationship, such as cardiovascular function [62], hormonal regulation [63], activities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neurogenesis [64], healthy behaviors, and stress management [65].

Moreover, the article posits that the linkage between relationship quality and cognitive function is mediated by the stress response. Positive, high-quality relationships characterized by social support can serve as coping resources, diminishing perceived stress levels and fostering cognitive well-being in older individuals.

Conclusions

Cognitive declines tied to aging-related pathology are essentially inevitable, with a multifaceted interplay of biological elements, societal factors, and lifestyle decisions contributing to these declines over the lifespan. This study's outcomes hold the potential to enrich aging theories and design targeted interventions aimed at improving the well-being of older individuals within the expanding elderly demographic, particularly in developing nations. It is advisable for both governmental and non-governmental entities to formulate comprehensive strategic frameworks to enhance the functional capabilities and uphold the autonomy of the elderly population.

Moreover, government policies should incentivize families and elderly care facilities to bolster social support systems for seniors, safeguarding them against cognitive deterioration associated with aging and mitigating subsequent adversities. This approach can help mitigate the detrimental impacts of stress while bolstering prospects for successful cognitive aging in older adults.

Limitations

This research has a number of limitations that should be acknowledged. The applicability of the findings to elderly populations in other regions may be somewhat limited, as this study exclusively focused on seniors in Tehran. Another limitation was the reliance on self-reported data from the elderly to complete the questionnaires, as some individuals may have provided inaccurate answers despite assurances of confidentiality. Given the confines of the current study, it is advisable for future research to explore alternative internal and external variables that could influence the mitigation of age-related cognitive effects in the elderly.

Additionally, due to the cross-sectional design of this research, it is recommended that longitudinal studies be conducted to gain a deeper understanding of the progressive factors contributing to cognitive decline across the lifespan.

Principles of research ethics

The ethical considerations of this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of Kharazmi University. Participants were informed of the study's objectives, and their information was treated confidentially. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Sponsorship

This study has not received any financial support from the government, private or non-profit organizations.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the elderly who sincerely cooperated with the research team in this study.

References

- Nejati V (2013) Cognitive abilities questionnaire: Development and evaluation of psychometric properties.

- Williams JMG, Broadbent K (1986) Distraction by emotional stimuli: Use of a Stroop task with suicide attempters. Br J Clin Psychol 25(2): 101-110.

- Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Folkman S (2006) A validity and reliability study of the coping self‐efficacy scale. Br j health psychol 11(3): 421-437.

- Cutrona C, Russell D, Rose J (1986) Social support and adaptation to stress by the elderly. Psychol aging 1(1): 47-54.

- Legdeur N, Tijms BM, Konijnenberg E, den Braber A, Ten Kate M, Sudre CH, et al. (2020) Associations of Brain Pathology Cognitive and Physical Markers With Age in Cognitively Normal Individuals Aged 60-102 Years. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 75(9): 1609-1617.

- Prince MJ, Wimo A, Guerchet MM, Ali GC, Wu Y-T, Prina M (2015) World Alzheimer Report 2015-The Global Impact of Dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends.

- Murman DL (2015) The impact of age on cognition. Semin hear 36(3): 111-121. Thieme Medical Publishers.

- Orock A, Logan S, Deak F (2020) Age-related cognitive impairment: Role of reduced synaptobrevin-2 levels in deficits of memory and synaptic plasticity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 75(9):1624-1632.

- Gallagher M, Okonkwo OC, Resnick SM, Jagust WJ, Benzinger TL, Rapp PR (2019) What are the threats to successful brain and cognitive aging? Neurobio aging 83: 130-134.

- Lövdén M, Fratiglioni L, Glymour MM, Lindenberger U, Tucker-Drob EM (2020) Education and cognitive functioning across the life span. Psychol Sci Public Interest 21(1): 6-41.

- Quach LT, Ward RE, Pedersen MM, Leveille SG, Grande L, Gagnon DR, et al. (2019) The association between social engagement, mild cognitive impairment, and falls among older primary care patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 100(8): 1499-1505.

- Singh T, Sharma S, Nagesh S (2017) Socio-economic status scales updated for 2017. Int J Res Med Sci 5(7): 3264-7.

- Kalaria RN, Maestre GE, Arizaga R, Friedland RP, Galasko D, Hall K, et al. (2008) Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia in developing countries: prevalence, management, and risk factors. Lancet Neurol 7(9): 812-826.

- Bonner CF (2015) Moderating effects of coping self-efficacy and coping diversity in the stress health relationship in African American college students: Old Dominion University.

- Hladek MD, Gill J, Bandeen Roche K, Walston J, Allen J, Hinkle JL, et al. (2020) High coping self-efficacy associated with lower odds of pre-frailty/frailty in older adults with chronic disease. Aging Ment Health 24(12): 1956-1962.

- Shields GS, Sazma MA, Yonelinas AP (2016) The effects of acute stress on core executive functions: A meta-analysis and comparison with cortisol. Neuroscie Biobehav Rev 68: 651-668.

- Gagnon SA, Wagner AD (2016) Acute stress and episodic memory retrieval: neurobiological mechanisms and behavioral consequences. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1369(1): 55-75.

- Milam LA, Cohen GL, Mueller C, Salles A (2019) The relationship between self-efficacy and well-being among surgical residents. J Surg Edu 76(2): 321-328.

- Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho A-R, Kim T, Park JK (2018) Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr psychiatry 87: 123-127.

- Cohen S, Wills TA (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol bull 98(2): 310-357.

- Dykstra P (2015) Aging and social support.

- Hu B, Li L (2020) The protective effects of informal care receipt against the progression of functional limitations among Chinese older people. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 75(5): 1030-1041.

- Dritschel BH, Williams J, Baddeley AD, Nimmo Smith I (1992) Autobiographical fluency: A method for the study of personal memory. Mem cognit 20(2): 133-140.

- Dalglish C, Therin F (2003) Leadership Perceptions: Small versus Large Businesses the Training Implications. Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand 16th Conference 2003. University of Ballarat.

- Massaldjieva RI (2018) Differentiating normal cognitive aging from cognitive impairment no dementia: a focus on constructive and visuospatial abilities. Gerontology 9: 167.

- Maldonado T, Orr JM, Goen JR, Bernard JA (2020) Age differences in the subcomponents of executive functioning. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 75(6): 31-55.

- Leibel DK, Williams MR, Katzel LI, Evans MK, Zonderman AB, Waldstein SR (2020) Relations of Executive Function and Physical Performance in Middle Adulthood: A Prospective Investigation in African American and White Adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 75(6): 56-68.

- Klaming R, Veltman DJ, Comijs HC (2017) The impact of personality on memory function in older adults—results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 32(7): 798-804.

- MacPherson SE, Allerhand M, Cox SR, Deary IJ (2019) Individual differences in cognitive processes underlying Trail Making Test-B performance in old age: the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Intelligence 75: 23-32.

- Karsazi H, Rezapour T, Kormi Nouri R, Mottaghi A, Abdekhodaie E, Hatami J (2021) The moderating effect of neuroticism and openness in the relationship between age and memory: Implications for cognitive reserve. Personality and Individual Differences 176: 110773.

- Neuman B, Fawcett J (2012) Thoughts about the Neuman systems model: A dialogue. Nursing sci quarterly 25(4): 374-376.

- Harding T, Lopez V, Klainin Yobas P (2019) Predictors of psychological well-being among higher education students. Psychol 10(4): 578.

- Albert MS, Jones K, Savage CR, Berkman L, Seeman T, Blazer D, et al. (1995) Predictors of cognitive change in older persons: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Psychol aging 10(4): 578-589.

- Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF (2011) Racial differences in the association of education with physical and cognitive function in older blacks and whites. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 66(3): 354-363.

- Sauter C, Danker Hopfe H, Loretz E, Zeitlhofer J, Geisler P, Popp R (2013) The assessment of vigilance: Normative data on the Siesta sustained attention test. Sleep Med 14(6): 542-548.

- Toh WX, Yang H, Hartanto A (2020) Executive function and subjective well-being in middle and late adulthood. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 75(6): 69-77.

- Serpell ZN, Esposito AG (2016) Development of executive functions: implications for educational policy and practice. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci 3(2): 203-210.

- Old SR, Naveh Benjamin M (2008) Differential effects of age on item and associative measures of memory: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging 23(1): 104-118.

- Koen JD, Yonelinas AP (2014) The effects of healthy aging, amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease on recollection and familiarity: A meta-analytic review. Neuropsychol rev 24(3): 332-354.

- Addis DR, Barense M, Duarte A (2015) The Wiley handbook on the cognitive neuroscience of memory: John Wiley Sons.

- Maillet D, Rajah MN (2014) Age-related differences in brain activity in the subsequent memory paradigm: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 45: 246-257.

- Spreng RN, Wojtowicz M, Grady CL (2010) Reliable differences in brain activity between young and old adults: a quantitative meta-analysis across multiple cognitive domains. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 34(8): 1178-1194.

- Zheng L, Gao Z, Xiao X, Ye Z, Chen C, Xue G (2018) Reduced fidelity of neural representation underlies episodic memory decline in normal aging. Cereb Cortex 28(7): 2283-2296.

- Abdulrahman H, Fletcher PC, Bullmore E, Morcom AM (2017) Dopamine and memory dedifferentiation in aging. Neuroimage 153: 211-220.

- Goveas JS, Rapp SR, Hogan PE, Driscoll I, Tindle HA, Smith JC, et al. (2016) Predictors of optimal cognitive aging in 80+ women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 71(Suppl_1): 62-71.

- Mohammadi A, Abdollahi MH, Noury R, Hashemi Razini H, Shahgholian M. Prediction of Psychological Well-being Based on Cognitive failures and Negative Affect Mediated by Coping Self-efficacy and Social Support in the Elderly. Iranian J Ageing.

- Conway MA (2005) Memory and the self. J mem language 53(4): 594-628.

- Tulving E (2002) Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annu rev psychol 53(1): 1-25.

- Schacter DL, Addis DR, Buckner RL (2007) Remembering the past to imagine the future: the prospective brain. Nat rev Neurosci 8(9): 657-661.

- Wimmer GE, Shohamy D (2012) Preference by association: how memory mechanisms in the hippocampus bias decisions. Science 338(6104): 270-273.

- Rönnlund M, Nyberg L, Bäckman L, Nilsson L G (2005) Stability, growth, and decline in adult life span development of declarative memory: cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. Psychol Aging 20(1): 3-18.

- Korkki SM, Richter FR, Jeyarathnarajah P, Simons JS (2020) Healthy ageing reduces the precision of episodic memory retrieval. Psychol Aging 35(1): 124-142.

- Holahan CK, Holahan CJ (1987) Life Stress, Hassles, and Self‐Efficacy in Aging: A Replication and Extension 1. J Applied Soc Psychol 17(6): 574-592.

- Thomas AK, Karanian JM (2019) Acute stress, memory, and the brain. Brain Cogn 133: 1-4.

- Bandura A, Reese L, Adams NE (1982) Microanalysis of action and fear arousal as a function of differential levels of perceived self-efficacy. J pers soc psychol 43(1): 5-21.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1982) Stress, appraisal, and coping: Springer publishing company.

- Mayordomo T, Viguer P, Sales A, Satorres E, Meléndez JC (2016) Resilience and coping as predictors of well-being in adults. J psychol 150(7): 809-821.

- Zahodne LB (2021) Psychosocial protective factors in cognitive aging: A targeted review. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 36(7): 1266-1273.

- Holtzman RE, Rebok GW, Saczynski JS, Kouzis AC, Wilcox Doyle K, Eaton WW (2004) Social network characteristics and cognition in middle-aged and older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 59(6): 278-284.

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M (2009) Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: modeling the externalizing spectrum.

- Holt Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D (2015) Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect psychol sci 10(2): 227-237.

- Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A (2011) Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health psychol 30(4): 377-385.

- Knox SS, Uvnäs Moberg K (1998) Social isolation and cardiovascular disease: an atherosclerotic pathway? Psychoneuroendocrinology 23(8): 877-890.

- Stranahan AM, Khalil D, Gould E (2006) Social isolation delays the positive effects of running on adult neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci 9(4): 526-533.

- McHugh Power J, Carney S, Hannigan C, Brennan S, Wolfe H, Lynch M, et al. (2019) Systemic inflammatory markers and sources of social support among older adults in the Memory Research Unit cohort. J Health Psychol 24(3): 397-406.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.