Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Time-Frequency Spectral Analysis of Heart Rate Variability (HRV) in Large Populations in Correlation to Age and Gender

*Corresponding author: Jonathan RT Lakey, Department of Surgery and Biomedical Engineering, University of California Irvine, California, USA.

Received: September 10, 2024; Published: September 16, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.24.003159

Abstract

Heart rate variability (HRV) refers to the phenomenon of sinus heart rate changing periodically over a specific period of time. As individuals age, HRV changes, and elucidating the intrinsic connection between HRV and age serves an important reference for human health assessment and clinical diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases. This paper focuses on the correlation between HRV characteristics, including Heart Rate Average at rest, rmsSD, SDNN, LF, HF, LF / HF, Total Power, Autonomic Tone and others, and age in large populations, and then apply the results of the correlation analysis to age assessment.

Keywords: Time frequency analysis, Heart rate, Spectral analysis

Introduction

Heart rate variability (HRV) is defined as the periodic change in sinus heart rate over a specified time interval, which is characterized by the minor discrepancy between the initial and subsequent heartbeat cycles [1,2]. In recent years, a growing number of studies have confirmed the close relationship between autonomic nervous system activity and the development of cardiovascular disease [3,4]. HRV represents an indirect method for assessing the activity of the autonomic nervous system, and has been identified as a marker of cardiovascular risk [5,6]. The initial discovery of the use of HRV in the context of cardiovascular disease was made by in the early 1970 [7-9]. Their findings indicated that a reduction in HRV in patients who had experienced a myocardial infarction often preceded a higher mortality rate [10]. Currently, HRV can be monitored outside the hospital using portable electrocardiographic devices or wearable electrocardiographic sensors [11]. HRV can be employed to reflect the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, as well as their respective effects on cardiovascular activity. Furthermore, HRV is currently regarded as the most effective approach for evaluating the functional status of the human autonomic nervous system, given its non-invasive, rapid, and quantifiable advantages [12]. Consequently, HRV is an effective approach to detecting organic cardiac pathologies, including heart failure, coronary artery disease, and other related conditions. Given these advantages, it is now widely recognized that HRV is the optimal method for assessing the functional status of the human autonomic nervous system [13].

With the progression of age, a multitude of organic cardiac lesions may become discernible. It is therefore imperative to assess the relationship between HRV and age in order to facilitate the prediction of cardiac pathology. It has been demonstrated that HRV undergoes changes with advancing age. This equilibrium between HRV and the activity of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves is progressively disrupted, which is manifested in the autonomic nervous system by a decrease in its overall activity and a weakening of its regulatory capacity [14]. Furthermore, a negative correlation has been identified between the reduction in HRV and the prevalence of cardiovascular disease, as well as mortality. To ascertain whether the alteration in HRV is a typical consequence of the aging process or is attributable to other factors, such as disease, it is essential to elucidate the intrinsic relationship between HRV and age.

A detailed analysis of the correlation between HRV and age, and the clarification of the correlation between the two, provides a theoretical basis for researching and exploring the status of autonomic function in the elderly in clinical medicine. Furthermore, it provides a theoretical basis for further diagnosis and prevention of other diseases, enabling doctors to pay attention to the status of autonomic function in a timely manner and monitor the condition of autonomic function in a targeted manner. This allows for the implementation of effective interventions. Conversely, it elucidates the correlation between HRV and age. Conversely, the correlation between HRV and age has been elucidated, and HRV can be employed to assess the biological age of the body and to evaluate the health status of the human body.

It is therefore necessary to study the inter-correlation and influence relationship between HRV and age by conducting the study on a sufficiently large sample of healthy subjects. In this paper, we aim to adopt this research perspective and investigate the correlation between HRV time-domain features, frequency-domain features, and nonlinear features and age in a healthy population. Furthermore, we intend to apply one of the HRV features that exhibits a correlation with age to the evaluation of age.

Materials and Methods

All data were obtained from an accessible database within Medeia Inc. (Santa Barbara, CA). This study was supported by an external IRB review and approval (Argus, Scottsdale AZ, 2023-01) Patients records were obtained and categorized into different age groups. The age groups were further divided into male and female, and the RR interval (RRI) was taken for each patient separately. The relationship between the different genders in each age group and HRV was then analyzed.

The linear characteristics of HRV encompass both time domain indicators and frequency domain analysis indicators. Time domain indicators include the following:

SDNN: The standard deviation of all normal-to-normal (NN) intervals. This indicator suggests the degree of sympathetic activity. The normal value is (141±39) ms. A lower value suggests that sympathetic activity is increased, and the body's ability to adapt to the external environment is weakened.

rMSSD: The root mean square of the difference between adjacent NN intervals. This indicator reflects the degree of vagal activity. The normal value is (27±12) ms.

The frequency domain analysis indexes of HRV include:

Total power (TP): This reflects the overall activity of the sympathetic nervous system and assesses the regulatory ability of the autonomic nervous system.

High frequency (HF) (0.15~0.40 Hz): a good indicator for evaluating the function of vagus nerve, affected by the depth of respiration.

Low frequency (LF) (0.04~0.15 Hz): controlled by sympathetic-vagal nervous system, some studies believe that it is affected by sympathetic nerves, and can be used as a reliable indicator to reflect the sympathetic activity of the heart, and is affected by the vascular pressure-regulating reflex.

The LF/HF ratio: is an indicator of changes in the balance of sympathetic-vagal tone.

For the RRI series of each age group, time-domain metrics and frequency-domain analysis metrics were calculated. The computed results were expressed as mean±standard deviation. The statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA), and significant differences between the tested indicators were deemed to exist at a probability level of P < 0.05.

Experimental Results

A total of 330,529 adult subjects (136,204 male subjects and 194,325 female subjects, aged 20-90 years) with RRI sequences were included in the database review providing a robust sample size for HRV analysis across different age and gender groups. The patients were categorized into 10 age groups: 20≤y≤25, n=5690; 25<y≤30, n=9820; 30<y≤35, n=15203; 35<y≤40, n=19000; 40<y≤45, n=24749; 45<y≤50, n=30779; 50<y≤65, n=38266; 60<y≤70, n=88787.

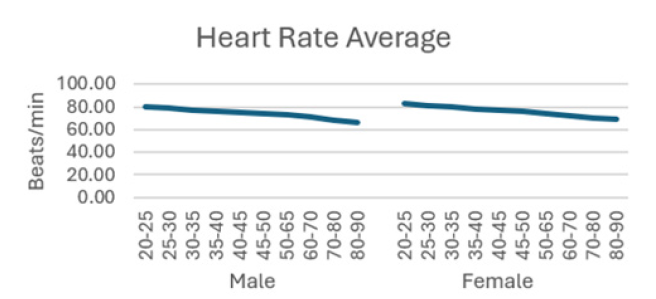

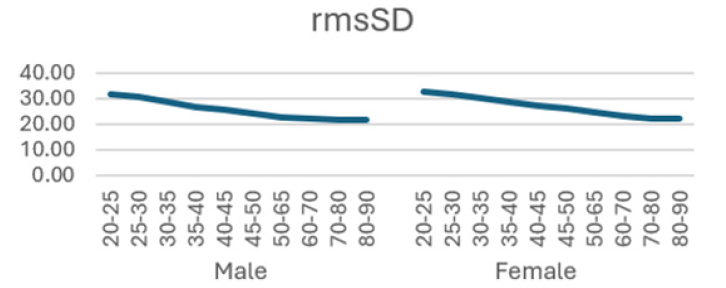

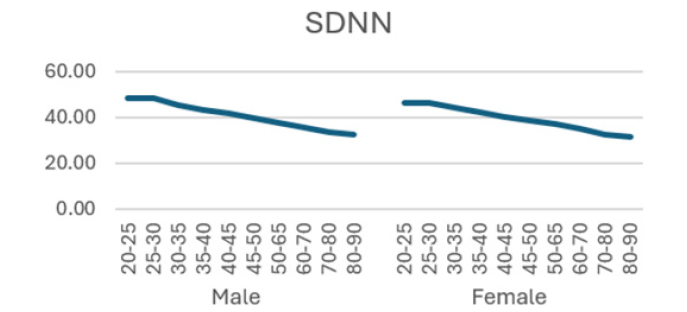

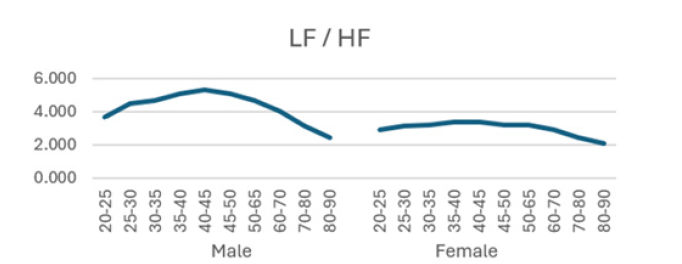

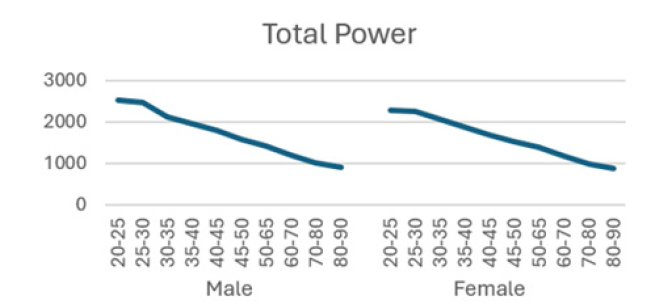

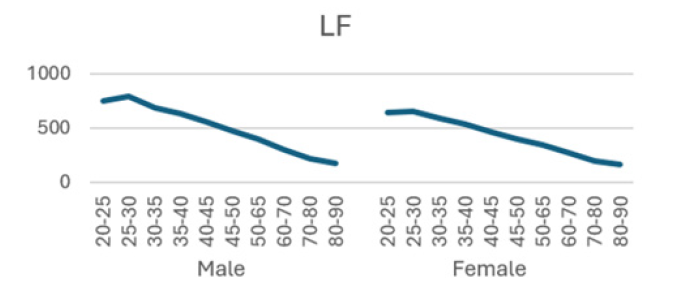

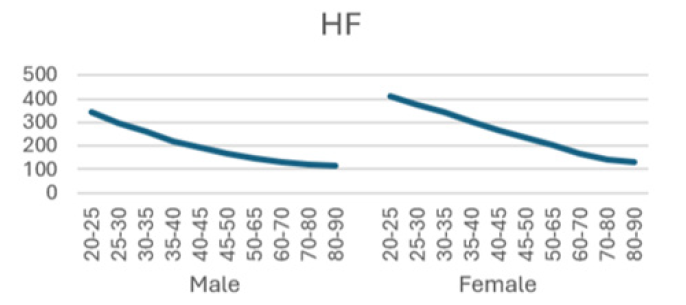

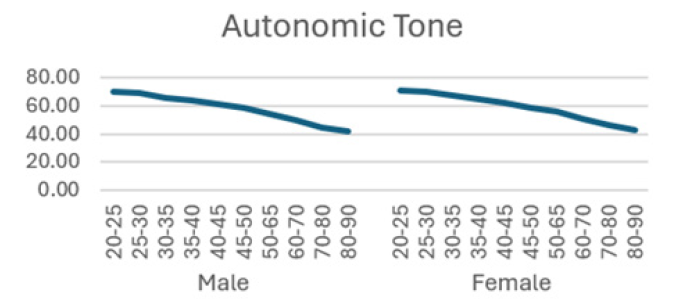

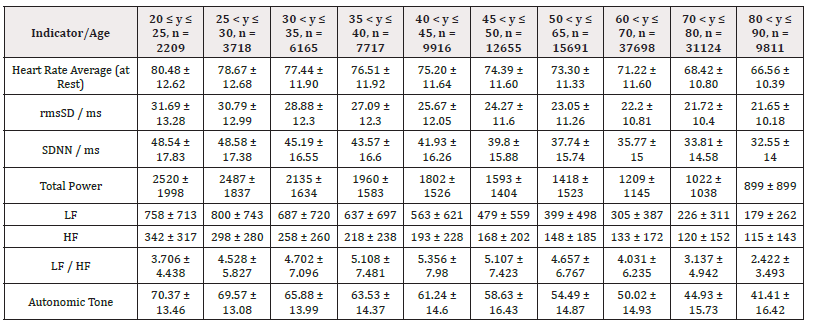

The detailed results from male subjects in this study, mean +/- standard error of the mean are presented in (Table 1) with the data shows the breakdown by age categories comparing average heart rate, rmsSDm/ ms, SDNN/ms, Total power, LF and HF and the ratio or LF/HF and the autonomic tone in the male subjects. There is a generalized trend to over time to observe a decrease from the initial values in the 20-25 year age group to the 80-90 age group in the parameters evaluated in this table. The data is also presented in (Figures 1-8) of this manuscript in a graphic description that details the changes over age that occur.

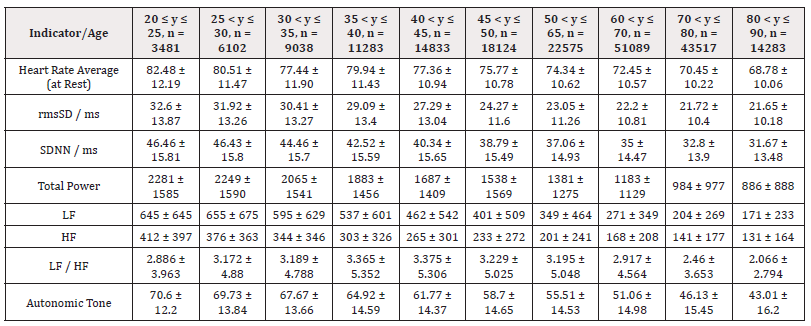

(Table 2) is similar to (Table 1) but (Table 2) is the detailed results from female subjects in this study, mean +/- standard error of the mean, with the data shows the breakdown by age categories comparing average heart rate, rmsSDm/ ms, SDNN/ms, Total power, LF and HF and the ratio or LF/HF and the autonomic tone in the female subjects. In our data analysis, there are both age and gender related differences and a a generalized trend to over time to observe a decrease from the initial values in the youngest group at 20-25 year age group to the oldest group at 80-90 age group in the parameters evaluated in this table.

Figure 1: Assessment of the effect of emergency radiation therapy on patients, an effect on overall survival (OS).

Figure 2: Assessment of the effect of emergency radiation therapy on patients, an effect on overall survival (OS).

Figure 3: Assessment of the effect of emergency radiation therapy on patients, an effect on overall survival (OS).

Figure 4: Assessment of the effect of emergency radiation therapy on patients, an effect on overall survival (OS).

Figure 5: Assessment of the effect of emergency radiation therapy on patients, an effect on overall survival (OS).

Figure 6: Assessment of the effect of emergency radiation therapy on patients, an effect on overall survival (OS).

Figure 7: Assessment of the effect of emergency radiation therapy on patients, an effect on overall survival (OS).

Figure 8: Assessment of the effect of emergency radiation therapy on patients, an effect on overall survival (OS).

Additionally, (Figures 1-8) depict the graphical distribution of each HRV metric across the different age groups. Specifically, LF/HF demonstrated a pattern of initial increase followed by decline with age. Other indicators, including HRV, rmsSD, SDNN, total power, LF, HF, and autonomic tones, all exhibited a negative correlation with age, indicating a general decline in heart rate variability as individuals age. Additionally, the indicators demonstrated variability across gender groups, with males and females showing different patterns in HRV metrics.

Discussion

This study represents an effort to analyze data from a large cohort of patients undergoing heart rate evaluation in a 3rd party external IBB approved study. Heart rate variability (HRV) serves as an indirect indicator of the dynamic regulation of cardiac activity by the autonomic nervous system. Abnormalities in HRV are often indicative of abnormalities in vagal and sympathetic nerve function. In recent years, there has been a growing interest among scholars and professional societies in the field of cardiology in studying HRV. This is because HRV is now recognized as a common quantitative index for determining the function of autonomic activity. Furthermore, changes in its value are important indicators of cardiovascular dysregulation [14] and various other clinical conditions.

HRV encompasses data such as heart rate average (at rest), SDNN and RMSSD, all of which may manifest fluctuations with age, exhibiting regular changes. A substantial body of research exists on the relationship between age and HRV. For example, Voss and colleagues investigated the association between short-term heart rate variability and age in a cohort of healthy individuals. To this end, they calculated 5-minute linear and nonlinear HRV characteristics for 1906 healthy samples from the KORA S4 database. Furthermore, they investigated the development of HRV characteristics by age (25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, and 65-74 years). The results of this study demonstrated that the majority of short-term HRV characteristics exhibited significant intergroup variability [12]. In 2018, Estevez-Baez et al. evaluated the impact of age, gender, and heart rate on HRV characteristics in 255 healthy adolescents, categorized into two groups (13-16 and 17-20 years old) and two groups of healthy young adults (21-24 and 25-30 years old). This was achieved through experimental calculation of time, frequency, and information domains of HRV, with changes in HRV characteristics modelled using multiple linear regression models to adjust for the effects of heart rate, age, and gender. The findings indicated a tendency for HRV eigenvalues to decrease with age [13]. In general, there was a negative correlation between age and HRV eigenvalues. Additionally, Abhishekh et al. analyzed data from 189 subjects and found that SDNN, RMSSD, and total power were negatively correlated with age, indicating a decline in autonomic regulation of the heart as age increases [18]. Conversely, the LF/HF ratio showed a positive correlation with age, suggesting a relative increase in sympathetic activity. The study concluded that overall autonomic control of the heart decreases with aging, and females exhibited greater vagal tone compared to males.

In this study, the RRI sequences of 33,0529 subjects in the database were analyzed to obtain their HRV indicators, including rMSSD, SDNN, LF, HF, LF/HF and others. The study revealed that all the indicators exhibited a correlation with gender and a negative correlation with age, with the exception of LF/HF, which demonstrated a pattern of initial increase followed by a decline with age.

RMSSD

RMSSD is obtained by first calculating the time difference (in milliseconds) between each successive heartbeat, then squaring each value and averaging the results, and then taking the square root of the total. This process captures the beat-to-beat variability of the heart rate and is able to reflect the activity of the vagus nerve [15,16]. Most studies have shown a negative correlation between rMSSD and age [17], although Glaucylara, et al. showed a U-shaped change in rMSSD with age [18]. A study concluded that higher RMSSD in COVID-19 patients is linked to lower inflammation levels, a reduced need for treatment, and a shorter hospital stay [23]. Another study found that patients with diabetes and arterial stiffness had lower RMSSD, which is associated with a worse cardiovascular risk profile. These findings suggest that RMSSD is correlated with positive clinical outcomes [26]. Our results demonstrated a declining trend in rMSSD with age, with a more pronounced decline observed in females. This suggests a reduction in vagal mobility of HRV with age, indicating a loss of cardiovascular system variability during the natural aging process.

SDNN

The standard deviation of the normalized NN intervals (SDNN) is expressed in milliseconds [15]. SDNN values can be used to predict the morbidity and mortality associated with heart disease. They are negatively correlated with heart risk, whereby values above 100 ms indicate a healthy state, while values below 50 ms are indicative of an unhealthy state [19,20,26] study showed that SDNN decreased linearly with age in 553 healthy participants, with males exhibiting significantly higher values than females [22]. In a study conducted by Beckers et al., 24-hour electrocardiogram (ECG) signals were recorded from 276 healthy subjects aged 18 to 71 years. The findings indicated a decline in SDNN values with advancing age [27]. The results align with our study, demonstrated that SDNN values were slightly lower in women than in men and exhibited a progressive decline with age, indicating an incremental increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease in the elderly.

LF/HF

Low frequency (LF) corresponds to variability in the frequency range of 0.04 Hz to 0.15 Hz and is primarily regulated by the sympathetic nervous system. The LF component of the spectrum is indicative of the sympathetic regulation of heart rate variability and is associated with stress and mood in vivo. It primarily reflects stress receptor activity at rest [26]. In contrast, high frequency (HF) corresponds to variability in the frequency range of 0.15 to 0.40 Hz and is reflective of parasympathetic activity [25]. A reduction in HF typically indicates a deterioration in cardiovascular health, which may be indicative of an increased risk of cardiovascular disease [24]. The LF/HF ratio is a measure of the relative activity levels of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Higher values indicate increased sympathetic activity, whereas lower values imply a predominance of parasympathetic activity. This is a sensitive predictor of arrhythmia, and changes in values often imply an unstable electrical activity of the heart. Our results demonstrated a decline in both LF and HF with age, accompanied by an initial increase and subsequent decline in LF/HF, exhibiting an "n" pattern. It seems reasonable to posit that middle-aged individuals are more susceptible to autonomic nervous system dysfunction as a consequence of the elevated LF/HF ratio, which may be attributed to the persistent sympathetic hyperactivity induced by their fast-paced occupational circumstances [27-32].

Limitation

The limitations of this study include a retrospective and non-randomized design. Future prospective randomized controlled trials are needed to validate these observations.

Conclusion

This study represents a large data set collected over several years in patients. We performed an external IRB reviewed and approved study of the data. The HRV indices which we evaluated included heart rate, rmsSD, SDNN, total power, and LF and HF including the ratio of LF/HF, demonstrate a correlation with age, exhibiting either an increase or a decrease with advancing age. This trend highlights the potential of HRV as a valuable tool in understanding the physiological changes that occur with aging. Additionally, gender differences in HRV indices suggest that both age and sex play crucial roles in shaping heart rate variability patterns. As such, HRV analysis may offer important insights into cardiovascular health as well as other conditions and can be used as a non-invasive means to assess the likelihood of developing heart and other diseases. We separated out the male from female values for the HRV parameters in this evaluation.

Further research is warranted to refine the application of HRV metrics in predicting heart disease risk, considering the combined effects of age, gender, and other contributing factors.

References

- Li K, Cardoso C, Moctezuma Ramirez A, Elgalad A, Perin E (2023) Heart Rate Variability Measurement through a Smart Wearable Device: Another Breakthrough for Personal Health Monitoring? Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(24): 7146.

- Musayev O, Kayikcioglu M, Shahbazova S, Nalbantgil S, Mogulkoc N, et al (2023) Could Heart Rate Variability Serve as a Prognostic Factor in Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension? A Single-center Pilot Study. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars 51(7): 454-463.

- Lown B, Verrier RL (1976) Neural activity and ventricular fibrillation. N Engl J Med 294(21): 1165-1170.

- Ziemssen T, Siepmann T (2019) The Investigation of the Cardiovascular and Sudomotor Autonomic Nervous System-A Review. Front Neurol 10: 53.

- Cygankiewicz I, Zareba W (2013) Heart rate variability. Handb Clin Neurol 117: 379-393.

- Xhyheri B, Manfrini O, Mazzolini M, Pizzi C, Bugiardini R (2012) Heart rate variability today. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 55(3): 321-331.

- Danev S (1970) Heart rate at various types of information coding, under laboratory conditions. Activ Nerv 10(1): 15-21.

- Danev S, Winter E (1970) Expectations, attention and heart rate deceleration, NIPG, Leiden, (Int. Report).

- Danev S, Winter E (1970) "Time Stress" and the relation between decision and motion times. NIPG, Leiden (Int. Report).

- Chorro FJ, Guerrerro J, Bataller M, Sanchis J, Burguera M, et al (1994) [The spectral analysis of heart rate variability. The methodological aspects]. Rev Esp Cardiol 47(4): 209-220.

- Rajendra Acharya U, Paul Joseph K, Kannathal N, Lim CM, Suri JS (2006) Heart rate variability: a review. Med Biol Eng Comput 44(12): 1031-1051.

- Dantas EM, Kemp AH, Andreao RV, da Silva VJD, Brunoni AR, et al (2018) Reference values for short-term resting-state heart rate variability in healthy adults: Results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health-ELSA-Brasil study. Psychophysiology 55(6): e13052.

- Voss A, Schroeder R, Vallverdu M, Schulz S, Cygankiewicz I, et al (2013) Short-term vs. long-term heart rate variability in ischemic cardiomyopathy risk stratification. Front Physiol 4: 364.

- Berntson GG, Bigger JT, Eckberg DL, Grossman P, Kaufmann PG, et al (1997) Heart rate variability: origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology 34(6): 623-648.

- Krause E, Vollmer M, Wittfeld K, Weihs A, Frenzel S, et al (2023) Evaluating heart rate variability with 10 second multichannel electrocardiograms in a large population-based sample. Front Cardiovasc Med 10: 1144191.

- Mulcahy JS, Larsson DEO, Garfinkel SN, Critchley HD (2019) Heart rate variability as a biomarker in health and affective disorders: A perspective on neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage 202: 116072.

- Paniccia M, Verweel L, Thomas S, Taha T, Keightley M, et al (2017) Heart Rate Variability in Healthy Non-Concussed Youth Athletes: Exploring the Effect of Age, Sex, and Concussion-Like Symptoms. Front Neurol 8: 753.

- Voss A, Heitmann A, Schroeder R, Peters A, Perz S (2012) Short-term heart rate variability--age dependence in healthy subjects. Physiol Meas 33(8): 1289-1311.

- Estevez Baez M, Carricarte Naranjo C, Jas Garcia JD, Rodriguez Rios E, Machado C, et al (22019) Influence of Heart Rate, Age, and Gender on Heart Rate Variability in Adolescents and Young Adults. Adv Exp Med Biol 1133: 19-33.

- Abhishekh HA, Nisarga P, Kisan R, Meghana A, Chandran S, et al (2013) Influence of age and gender on autonomic regulation of heart. J Clin Monit Comput 27(3): 259-264.

- Shaffer F, Ginsberg JP (2017) An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front Public Health 5: 258.

- DeGiorgio CM, Miller P, Meymandi S, Chin A, Epps J, et al (2010) RMSSD, a measure of vagus-mediated heart rate variability, is associated with risk factors for SUDEP: the SUDEP-7 Inventory. Epilepsy Behav 19(1): 78-81.

- Umetani K, Singer DH, McCraty R, Atkinson M (1998) Twenty-four hour time domain heart rate variability and heart rate: relations to age and gender over nine decades. J Am Coll Cardiol 31(3): 593-601.

- Shah AS, Jaiswal M, Dabelea D, Divers J, Isom S, et al (2020) Cardiovascular risk and heart rate variability in young adults with type 2 diabetes and arterial stiffness: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. J Diabetes Complications 34(10): 107676.

- Hunakova L, Sabaka P, Zvarik M, Mikolaskova I, Gidron Y, et al (2023) Linear and non‑linear indices of vagal nerve in relation to sex and inflammation in patients with Covid‑ Biomed Rep 19(5): 80.

- Geovanini GR, Vasques ER, de Oliveira Alvim R, Mill JG, Andreao RV, et al (2020) Age and Sex Differences in Heart Rate Variability and Vagal Specific Patterns - Baependi Heart Study. Glob Heart 15(1): 71.

- Kleiger RE, Miller JP, Bigger JT, Moss AJ (1987) Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 59(4): 256-262.

- Lopresti AL (2020) Association between Micronutrients and Heart Rate Variability: A Review of Human Studies. Adv Nutr 11(3): 559-575.

- Beckers F, Verheyden B, Aubert AE (2006) Aging and nonlinear heart rate control in a healthy population. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290(6): H2560-2570.

- McCraty R, Shaffer F (2015) Heart Rate Variability: New Perspectives on Physiological Mechanisms, Assessment of Self-regulatory Capacity, and Health risk. Glob Adv Health Med 4(1): 46-61.

- Quintana DS, Elstad M, Kaufmann T, Brandt CL, Haatveit B, et al (2016) Resting-state high-frequency heart rate variability is related to respiratory frequency in individuals with severe mental illness but not healthy controls. Sci Rep 6: 37212.

- Thayer JF, Yamamoto SS, Brosschot JF (2010) The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Int J Cardiol 141(2): 122-131.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.