Mini Review

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

A Mini Review on Biomedical Applications of Chitosan (CHI)

*Corresponding author: Ömer Fırat Turşucular, R&D Chief, Hatin Textile, and Hatin Tex Weaving Companies, DOSAB, Bursa Province, Turkey, ORCID ID: 0000-0003-1162-0742.

Received: November 25, 2024; Published: December 05, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.25.003275

Abstract

The purpose of this theoretical and technical mini-review study was aimed to present all technical information about Chitosan (CHI) in general and to present all necessary technical information about both general and specific Chitosan (CHI) applications in the biomedical field. As a result of this theoretical and technical mini-compilation study that low nanofiber diameters (below 100 nm), at high concentrations (minimum 1% and maximum 4%) and around pH 5 for CHI, its superior biological properties were combined with various biocompatible polymeric materials and were generally used by electrospinning (in nanofiber form) and hybrid coating (in nanoparticle, film or membrane forms) can be used biologically in in-vitro and invivo environments in biomedical applications such as wound dressing, bone regeneration and cardiovascular graft applications, which were specific biomedical applications. It was found that by culturing human fibroblast and myoblast protein cells, the antimicrobial effect and biocompatibility increased, surface adhesion, surface morphology and surface topology improved, and reduced cell cytotoxicity in the human body. Moreover, CHIs between 70% and 85% N-Deacetylation Degree (DD) had the high chemical reactivity of the primary amino groups in its chemical structure. Thus, its high chemical cross-linking was the most important factor that ensured its effectiveness in biomedical applications.

Keywords: Chitosan, Its properties, Its general applications, Its specific applications

Introduction

The purpose of this theoretical and technical mini-review study was aimed to present all technical information about Chitosan (CHI) in general and to present all necessary technical information about both general and specific Chitosan (CHI) applications in the biomedical field. This theoretical and technical mini-review study was examined in 4 main sub-sections. In the first part, the types, chemical structures, and properties of chitin and Chitosan (CHI) were examined in technical detail. In the second part, the effects of Chitosan (CHI) from chitin on the production process and process parameters were examined in technical detail. In the third part, some material combinations of Chitosan (CHI) and their general and biomedical applications were examined in technical detail. In the last part, specific biomedical applications of CHI were examined in technical detail.

Chemical Structures and Properties of Chitin and Chitosan (CHI)

Chitin, (β-[1-4]-poly-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine) is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature after cellulose. [1,3,5,7,11- 14,16,23,26]. Chitin and Chitosan (CHI) are known as biopolymers and are widely used in biomedical applications due to their properties such as biocompatibility, high porosity, biodegradability, predictable degradation rate, hydrophobicity, molecular adsorption, structural integrity and non-hemogenic, non-immunogenic, non-toxic, non-thrombogenic, non-carcinogenic and non-pathogenic to cells. [1-30]. Chitin also has antimicrobial and moisturizing properties. The reason why it has these properties is that it has extremely chemically reactive primary amino groups in its chemical structures [1]. Depending on the source of chitin, it generally has chemical structures into two allomorphs, namely α and β forms, which can be characterized by infrared and solid-state NMR spectroscopy along with X-ray diffraction.

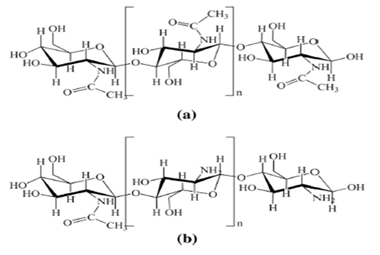

γ-Chitin is a third allomorph chemical structure that has also been identified. Allomorphs have different behavior in the orientation of microfibrils. [1,16]. The unit cell consists of two N,N’-diacetylchitobiose units forming two chains in an antiparallel arrangement for the chemical structure of α-chitin. Therefore, adjacent polymer chains extend in opposite directions, held together by 06- H→06 hydrogen bonds, and the chains are held in layers by 07→HN hydrogen bonds. It is a less common chemical form of chitin and its unit cell for the chemical structure of β-chitin. It is N,N’-diacetylchitobiose unit, yielding a polymer stabilized as a rigid ribbon in the same manner as α-chitin by 03 → 05 intramolecular H bonds. Chemical chains in this structure are held together in layers by C=O→H-N H bonds and -CH2OH side chains between amide groups. Thus, it leads to the formation of interlayer -H bonds to carbonyl oxygens in adjacent chains. (06)-H→07). This chemical structure provides a structure consisting of parallel poly-N-acetylglucosamine chains without -H bonds between the layers. [1,16]. The parallel arrangement of polymer chains in β-chitin provides greater flexibility than the antiparallel arrangement found in α-chitin. It has a mono-crystalline chemical structure. Moreover, the resulting polymer still has a very large tensile strength value. [1,5]. γ-Chitin is the third allomorph with mixed parallel and antiparallel orientations. It has been reported to occur in fungi. Chitin is always cross-linked to other structural components, except for β-chitin, which is found in diatoms [1]. The chemical structures of a) chitin and b) Chitosan (CHI) were presented in (Figure 1) [2].

Chitosan (CHI) was discovered by French professor Henri Braconnot in 1811 [3,4]. In another source, it was discovered by Rouget in 1859 using thermal and chemical methods. [15]. Chitosan (CHI) has the linear and semi-crystalline chemical structure of β(1-4) linked 2‑acetamido‑2‑deoxy‑β‑D‑glucose (N‑acetylglucosamine). [4-8,13,14,16,18,20-24,26,28]. The closed chemical formula of CHI is (C6H11O4N) [24]. Found in nature as regular macrofibrils, chitin is found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans, crabs and shrimps, as well as in the main structural components of the cell walls of fungi. [1-7,11,12,19,27].

Manufacturing Process and Process Parameters Effects of Chitin and Chitosan (CHI)

The average annual production amount is more than 1000 tons, and approximately 70% of it is produced from marine species by chemical processing [2]. In another source, it was reported that the annual production is in the range of 1010 to 1011 tons [11]. In this chemical process, the acetamide groups of the cellulose molecule are transformed into primary amino groups. Moreover, as the cationic density increases, the electrostatic attraction interaction increases. Thus, the degree of N-Deacetylation (DD) chemical process rate also increases. CHI has DD ranging from 30% to 99% [2,4,6,7,16,18,29]. Moreover, as the solution viscosity increases, the degree of N-Deacetylation (DD), molecular weight (Da), and degree of polymerization increase, but its solubility in its solution decreases [14,15,29]. In particular, solubility is poor in the CHI structure with DD above 85% [29].

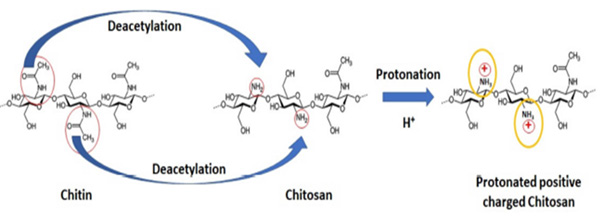

As for the production method from chitin to Chitosan (CHI) by N-Deacetylation Degree (DD) process has some production process parameters such as appropriate pH (1-14 usually between 4.7 and 5.3), chemical solution type (acidic and basic environments) and concentration (%c usually between 1% and 4%), bath ratio (M/L - usually 1:10), viscosity (Pa.s) temperature ((°C) usually between 65 °C to 100 °C), time (usually between 0.5 hours and 72 hours), pressure (atm), molecular size (nm usually below 100 nm), molecular weight (Da usually between 10,000 and 220,000) and degree of polymerization ((n) a few 100 monomer units), below at pH 6.5 so that it has 70% N-deacetylation [1-24,26-30]. In its industrial applications, it has a total process time of 1 to 72 hours, including treatment with 1M HCl for 16 to 48 hours and treatment with 2M NaOH for 17 to 72 hours. Long-term chemical processes for the isolation of chitin require more energy. Thus, its production cost increases. Bacteria cause degradation of chitin in both aqueous and soil structures [1,20,23]. The N-Deacetylation (DD) process, which is the chemical conversion process from chitin to CHI was presented in (Figure 2) [26].

General and Biomedical Applications of Chitosan (CHI) and It’s Combined with Some Materials

General application areas of CHI are textile wastewater recovery, textile finishing process, membrane, chelation of heavy metal ions, antibacterial, antioxidant biosensor, biotechnology, cosmetics, agricultural, cancer treatment, dental, orthopedics, bone regeneration, pharmaceutical, medical, and biomedical applications [1-30]. Chitin and CHI have a wide range of biomedical application areas such as tissue engineering, drug and gene transfer, wound healing, soft tissue implants, cartilage, bone, teeth, skin, heart and nerve healing, and stem cell technology. These biopolymers are biological chemicals that can be easily processed into a variety of products, including hydrogels, membranes, nanofibers, beads, micro/ nanoparticles, magnetic particles, micelles, films, plates, scaffolds, and sponges [1,4,6,8,9,12-30]. Nano Particles (NPs) with their size less than 100 nm are widely used in biomedical applications where qualities such as patient compliance, improved biodistribution, and intrabody site-specific drug distribution are sought [8,9,11- 15,18,20-30].

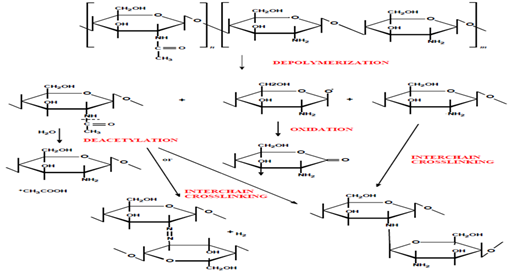

For biomedical applications, chitin is first converted into its N-deacetylated derivative, chitosan, and can be used either alone or in mixtures with various polymers [1,5-30]. The possible degradation mechanisms of the chemical structure of CHI were presented in (Figure 3) [27].

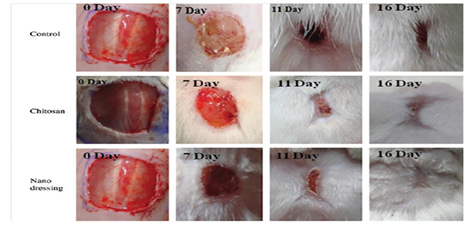

Application methods of CHI in biomedical applications generally are such as spraying, impregnation coating, film coating, hybrid coating, chemical induction, 3-D printing, solution preparation, sintering, electrophoretic storage, microwave radiation, freeze-drying, air-drying, sol-gel, and electrospinning methods [1-30]. CHI can be used with together some chemicals, and materials such as aloe-vera, albumin, hydrogel, silicate, Ag, AgNO3, Au, Ca, CaCO3, Mg, MgNO3, NaCl, NaOH, NaHCO3, Na3PO4, Si, SiO2, Ti, TiO2, Ti6AlV, BG, GO, HA, PA 6.6, PC, PU, PS, SI, ALG, COL, CNT, CMC, GEL, MMT, PAA, PEG, PEO, PES, PET, PCL, PLA, PLL, PSS, PVA, PVP, TPP, TPU, ZnO, CoPA, PANI, PLDA, PLGA, PMMA, PLAGA, TEOS, PAMAM, PEDOT, PUNIPAAm, and NIPAAm, It can be also used in biomedical application areas such as coating, antibacterial, membrane, and drug transportation [5-30]. The time-dependent in-vivo and in-vitro effects of CHI on wound healing were presented in (Figure 4) [15].

Biomedical Specific Applications of Chitosan (CHI)

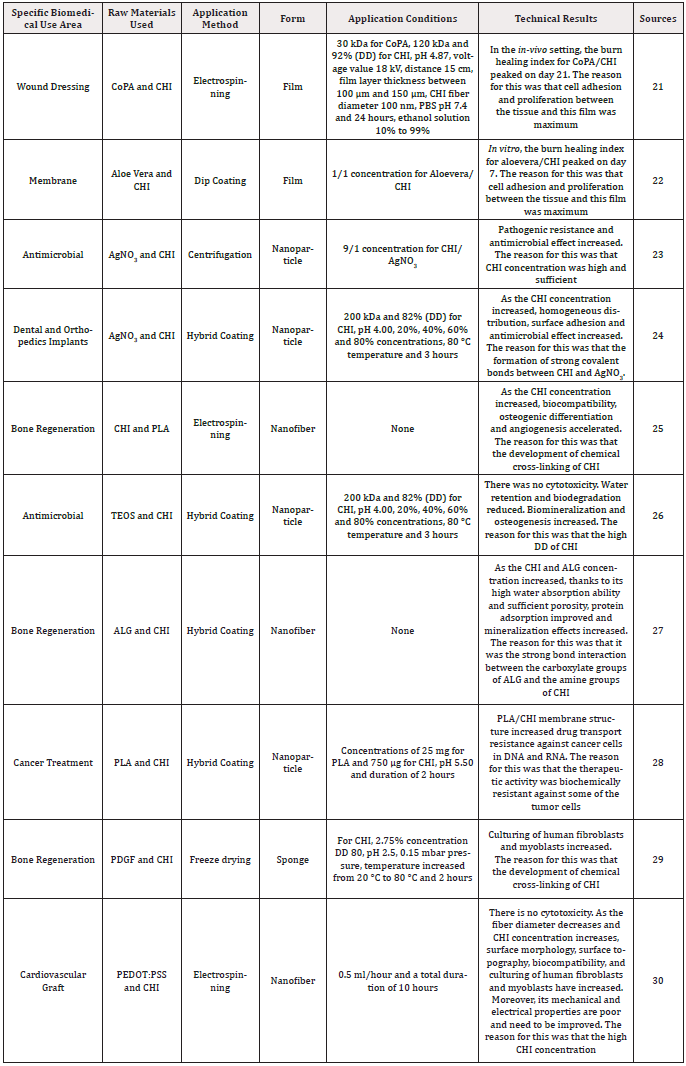

The technical information of CHI regarding its specific biomedical usage areas was presented in (Table 1) [21-30].

Conclusion

The purpose of this theoretical and technical mini-review study was aimed to present all technical information about Chitosan (CHI) in general and to present all necessary technical information about both general and specific Chitosan (CHI) applications in the biomedical field. Chitin, (β-(1–4)-poly-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine) is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature after cellulose. Chitosan (CHI) has the linear and semi-crystalline chemical structure of β (1-4) linked 2‑acetamido‑2‑deoxy‑β‑D‑glucose (N‑acetylglucosamine). The closed chemical formula of CHI is (C6H11O4N) n. Found in nature as regular macrofibrils, chitin is found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans, crabs, and shrimps, as well as in the main structural components of the cell walls of fungi. It was reported that the annual production is in the range of 1010 to 1011 tons. In this chemical process, the acetamide groups of the cellulose molecule are transformed into primary amino groups. Moreover, as the cationic density increases, the electrostatic attraction interaction increases. Thus, the degree of N-Deacetylation (DD) chemical process rate also increases. CHI has DD ranging from 30% to 99%. Moreover, as the solution viscosity increases, the degree of N-Deacetylation (DD), molecular weight (Da), and degree of polymerization increase, but its solubility in its solution decreases. In particular, solubility is poor in the CHI structure with DD above 85%. As for the production method from chitin to Chitosan (CHI) by N-Deacetylation Degree (DD) process has some production process parameters such as appropriate pH (1-14 usually between 4.7 and 5.3), chemical solution type (acidic and basic environments) and concentration (%c usually between 1% and 4%), bath ratio (M/L - usually 1:10), viscosity (Pa.s) temperature ((°C) usually between 65 °C and 100 °C), time (usually between 0.5 hours and 72 hours), pressure (atm), molecular size (nm usually below 100 nm), molecular weight (Da usually between 10,000 and 220,000) and degree of polymerization ((n) a few 100 monomer units), below at pH 6.5 so that it has 70% N-deacetylation. For biomedical applications, chitin is first converted into its N-deacetylated derivative, chitosan, and can be used either alone or in mixtures with various polymers. Chitin and CHI have a wide range of biomedical application areas such as tissue engineering, drug and gene transfer, wound healing, soft tissue implants, cartilage, bone, teeth, skin, heart and nerve healing, and stem cell technology. These biopolymers are biological chemicals that can be easily processed into a variety of products, including hydrogels, membranes, nanofibers, beads, micro/nanoparticles, magnetic particles, micelles, films, plates, scaffolds, and sponges.

Nanoparticles (NPs) with their size less than 100 nm are widely used in biomedical applications where qualities such as patient compliance, improved biodistribution, and intrabody site-specific drug distribution are sought. As a result of this theoretical and technical mini-compilation study that low nanofiber diameters (below 100 nm), at high concentrations (minimum 1% and maximum 4%), and around pH 5 for CHI, its superior biological properties were combined with various biocompatible polymeric materials and were generally used by electrospinning (in nanofiber form) and hybrid coating (in nanoparticle, film or membrane forms) can be used biologically in in-vitro and in-vivo environments in biomedical applications such as wound dressing, bone regeneration and cardiovascular graft applications, which were specific biomedical applications. It was found that by culturing human fibroblast and myoblast protein cells, the antimicrobial effect and biocompatibility increased, surface adhesion, surface morphology, and surface topology improved, and reduced cell cytotoxicity in the human body. Moreover, CHIs between 70% and 85% N-deacetylation degree (DD) had the high chemical reactivity of the primary amino groups in its chemical structure. Thus, its high chemical cross-linking was the most important factor that ensured its effectiveness in biomedical applications.

Acknowledgements

The author declares that there is no acknowledgements in this paper.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Elieh-Ali-Komi Daniel, Michael R Hamblin (2016) Chitin and chitosan: production and application of versatile biomedical nanomaterials. International Journal of Advanced Research 4(3): 411-417.

- Islam Shafiqul, MA Rahman Bhuiyan, M N Islam (2017) Chitin and chitosan: structure, properties and applications in biomedical engineering. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 25(1): 854-866.

- Yadav Preeti, Harsh Yadav, Veena Gowri Shah, Gaurav Shah, Gaurav Dhaka et al., (2015) Biomedical biopolymers, their origin and evolution in biomedical sciences: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR 9(9): 21-25.

- Periayah Mercy Halleluyah, Ahmad Sukari Halim, Arman Zaharil Mat Saad (2016) Chitosan: A promising marine polysaccharide for biomedical research. Pharmacognosy Reviews 10(19): 39-42.

- Usman Ali, Khalid Mahmood Zia, Mohammad Zuber, Shazia Tabasum, Saima Rehman et al., (2016) Chitin and chitosan-based polyurethanes: A review of recent advances and prospective biomedical applications. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 86(1): 630-645.

- Moura Duarte, João F Mano, Maria C Paiva, Natália M Alves (2016) Chitosan nanocomposites based on distinct inorganic fillers for biomedical applications. Science and Technology of Advanced Materials 17(1): 626-643.

- Szulc Marta, Katarzyna Lewandowska (2022) Biomaterials based on chitosan and its derivatives and their potential in tissue engineering and other biomedical applications-A review. Molecules 28(1): 247.

- Rizeq Balsam R, Nadin N Younes, Kashif Rasool, Gheyath K Nasrallah (2019) Synthesis, bioapplications, and toxicity evaluation of chitosan-based nanoparticles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20(22): 5776.

- Zhao Dongying, Shuang Yu, Beini Sun, Shuang Gao, Sihan Guo et al., (2018) Biomedical applications of chitosan and its derivative nanoparticles. Polymers 10(4): 462.

- Kalantari Katayoon, Amalina M Afifi, Hossein Jahangirian, Thomas J Webster (2019) Biomedical applications of chitosan electrospun nanofibers as a green polymer–Review. Carbohydrate Polymers 207(1): 588-600.

- Azuma Kazuo, Shinsuke Ifuku, Tomohiro Osaki, Yoshiharu Okamoto, Saburo Minami et al., (2014) Preparation and biomedical applications of chitin and chitosan nanofibers. Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 10(10): 2891-2920.

- Kim Yevgeniy, Zharylkasyn Zharkinbekov, Kamila Raziyeva, Laura Tabyldiyeva, Kamila Berikova et al., (2023) Chitosan-based biomaterials for tissue regeneration. Pharmaceutics 15(3): 807.

- Song Richard, Maxwell Murphy, Chenshuang Li, Kang Ting, Chia Soo et al., (2018) Current development of biodegradable polymeric materials for biomedical applications. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 12(1): 3117-3145.

- Balan Vera, Liliana Verestiuc (2014) Strategies to improve chitosan hemocompatibility: A review. European Polymer Journal 53(1): 171-188.

- Jangid, Nirmala Kumari, Deepa Hada, Kavita Rathore (2019) Chitosan as an emerging object for biological and biomedical applications. Journal of Polymer Engineering 39(8): 689-703.

- Anitha A (2014) Chitin and chitosan in selected biomedical applications. Progress in Polymer Science 39(9): 1644-1667.

- Silva, Simone Santos (2013) Effect of crosslinking in chitosan/aloe vera-based membranes for biomedical applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 98(1): 581-588.

- Ou Yi, Meng Tian (2021) Advances in multifunctional chitosan-based self-healing hydrogels for biomedical applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 9(38): 7955-7971.

- Chatterjee Sudipta, Patrick Chi-leung Hui, Chi-wai Kan (2018) Thermoresponsive hydrogels and their biomedical applications: Special insight into their applications in textile based transdermal therapy. Polymers 10(5): 480.

- Rajabi Mina (2021) Chitosan hydrogels in 3D printing for biomedical applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 117768-260(1): 1-20.

- Shabunin, Anton S (2019) Composite wound dressing based on chitin/chitosan nanofibers: Processing and biomedical applications. Cosmetics 16-6(1): 1-10.

- Ahmed Shakeel, Saiqa Ikram (2016) Chitosan based scaffolds and their applications in wound healing. Achievements in the Life Sciences 10(1): 27-37.

- Ke Cai-Ling, Fu-Sheng Deng, Chih-Yu Chuang, Ching-Hsuan Lin (2021) Antimicrobial actions and applications of chitosan. Polymers 13(6): 904.

- Sharifianjazi Fariborz, Samad Khaksar, Amirhossein Esmaeilkhanian, Leila Bazli, Sara Eskandarinezhad et al., (2022) Advancements in fabrication and application of chitosan composites in implants and dentistry: A review. Biomolecules 12(2): 155.

- Tao Fenghua, Yanxiang Cheng, Xiaowen Shi, Huifeng Zheng, Yumin Du et al., (2020) Applications of chitin and chitosan nanofibers in bone regenerative engineering. Carbohydrate Polymers 230(1): 115658.

- Aguilar Alicia, Naimah Zein, Ezeddine Harmouch, Brahim Hafdi, Fabien Bornert et al., (2019) Application of chitosan in bone and dental engineering. Molecules 24(16): 3009.

- Szymańska Emilia, Katarzyna Winnicka (2015) Stability of chitosan-a challenge for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Marine Drugs 13(4): 1819-1846.

- Babu Anish, Rajagopal Ramesh (2017) Multifaceted applications of chitosan in cancer drug delivery and therapy. Marine Drugs 15(4): 96.

- Aravamudhan Aja (2014) Natural polymers: polysaccharides and their derivatives for biomedical applications. Natural and synthetic biomedical polymers. Elsevier 1(1): 67-89.

- Abedi Ali, Mahdi Hasanzadeh,Lobat Tayebi (2019) Conductive nanofibrous Chitosan/PEDOT: PSS tissue engineering scaffolds. Materials Chemistry and Physics 121882-237(1): 1-8.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.