Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Situational Division and the Dynamics of Rural Health Care of Blacks in the Former Transvaal Province of South Africa During Apartheid Era, 1948-1980s

*Corresponding author: MW Maepa, University of Pretoria (UP), Pretoria, South Africa.

Received: November 28, 2024; Published: December 03, 2024

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2024.25.003272

Abstract

The economic conditions of blacks, which resulted in the increase of the disease burden, had during the 1930s and 1940s prompted the Union Department of Health to restructure the healthcare services to improve provision and access. This resulted in tentative steps being taken towards the creation of a national health care service system. However, the separate development policies of the new apartheid masterminds led to the disruption of this process. This article seeks to highlight the impact of the advent of apartheid on the healthcare service provision for rural blacks in the former Transvaal between the late 1940s and 1980s, and explore these developments and comment on their nature and pattern. Focus will also be on the areas of the former homelands of Lebowa, Venda and Gazankulu in the northern Transvaal. The article also argues that attempts by the apartheid government to solve health challenges of the blacks through segregated legislations triggered more resistant reactions from antiapartheid organizations, and in the process forcing the government to continue with health reforms in favour of apartheid. The conclusive part of this article will highlight the impact of apartheid on health since the inception of democratic government in 1994, including attempts to influence further health reforms of which the recent National Health Insurance is no exception.

Keywords: Apartheid health policies, South Africa, Transvaal homelands, Fragmented health services, Primary health care, National Health Insurance

Introduction

In South African context, signs of racial discrimination were in existence since colonialism. However, from the early 20th century the process got intensified and codified. The period following the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910 was followed by the passing of a variety of legislations governing the non-white affairs. The segregation policies set into motion processes of discrimination in all spheres of life, including unequal access to healthcare services. By the time National Party came to power after a victory during the 1948 general elections, suddenly new forms of marginalisation and ideological separation from whites against blacks endured. Gradually, blacks found themselves as victims of the renewed form of legislated segregation, which condemned them to the reserves and, later the homelands. The strengthening of apartheid since this period evoked a series of resistance from blacks which ranged from passive to militant reactions. Throughout the period between 1948 and 1980, various health reforms were passes by apartheid government but did not bring the envisaged total abolition of segregated healthcare services in favour of equal health for all South African citizens.

Apartheid and Healthcare in Historiographical Perspective

Apartheid health policies have been subject to continuing scholarly interest and there is a large body of historical work on this period. Scholars have been roundly critical of apartheid health policies, which not only reversed earlier gains in healthcare development, but also led to further deterioration of health conditions in the country. In his book titled South African Disease: Apartheid and Health Services, Cedric de Beer makes an interesting analysis of the relationship between social injustice and ill health in South Africa during apartheid era. The racial discrimination and apartheid since the 1948 election created conditions for the increase of diseases associated with poverty. Tuberculosis was among the most notorious of those diseases, which caused a great deal of ill health and high mortality among blacks due to the migrant labour system in the Transvaal mines. De Beer refers to the spread of this disease from the mines to the rural areas and the failure of the apartheid authorities to put in place adequate measures. De Beer further emphasises how apartheid since 1948 marginalised the blacks socially, economically and politically, particularly in the homelands, a situation that fostered the occurrence of diseases at alarming rates. Tackling these diseases through community or Primary Health Care (PHC), with the establishment of clinics, hospitals and community health centres, did not receive enough attention, as the focus of the apartheid state was to divide the country into several ethnic republics [1].

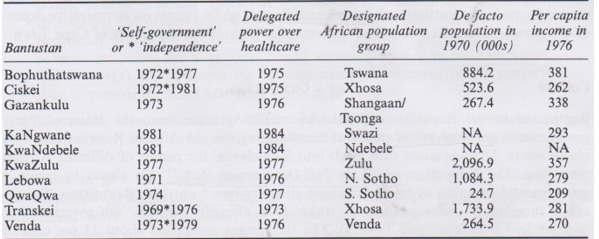

The negative consequences of apartheid were highlighted by Horwitz regarding the unequal distribution of health services between blacks and whites. In the homelands, the administration of health services by health workers was hampered by the overcrowding of black patients and poorly resourced health institutions. This inequality is clearly illustrated in Figure 1 below, which depicts a low level of African (black) expenditure between 1965 and 1987, followed by the coloureds, and then Indians, with the whites showing the highest per capita expenditure. The underfunded blacks were exposed to the diseases of which tuberculosis spread by the mine workers also increased ill-health and death [2].

The article written by Shula Marks and Neil Andersson entitled ‘Issues in the Political Economy of Health in Southern Africa’, and published in a special edition of the Journal of Southern African Studies, adopts a political economy approach to black health during apartheid. The two scholars show that the poor health profile of blacks was linked to their socio-economic status, which came about because of active policy discrimination and neglect by the apartheid state. The National Party’s short-lived health reform strategy was designed to cool down the black discontent as violence surged in the context of increases in preventable diseases [3]. Anne Digby has also analysed the effects of apartheid on health care of the blacks. Although acknowledging the negative developments of this period, Digby also shines a spotlight on the innovative, integrated health care policies adopted by some homeland governments from the 1970s to the 1990s, as they attempted to extend PHC services to the remote rural areas. Digby highlights the prioritisation of health care and expansion of a network of clinics and other health centres in the homelands and the assistance in the provision of resources to promote preventative health services [4]. Notwithstanding, analysis also highlights the little funds allocated to the homelands, leaving them to grapple with the prevention of the diseases such as cholera, malaria, polio, typhoid, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS [4].

The repressive and oppressive attitudes by the National Party government were entrenched massively during the 1950s, hence the slow pace in the development of community healthcare services by those in the medical field who supported reform measures as they were restricted by legislations. One can therefore argue that the roots of South Africa’s contemporary healthcare challenges and the dysfunctional systems that is failing to address the challenges can be traced back to, mostly, the period of racial subjugation and apartheid.

Homelands and Fragmented Healthcare Services

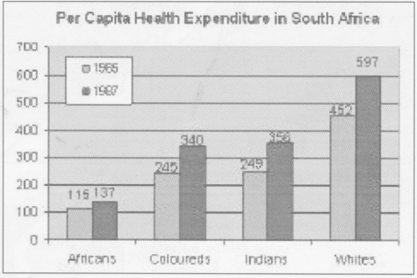

The homelands or Bantustans, which emerged from the National Party government’s apartheid policy, was aimed at transforming the old ‘African reserves’ where blacks were placed on separate lands based on different ethnic groups as depicted in the table below (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The reported list of homelands by the South African Department of Health in relation to the population and per capita income in the 1970s and early 1980s.

This new territorial alignment had a negative impact on the health services of the homelands. As a result, the Department of Health and Welfare in the homelands realized that the only way to manage this challenge was through the implementation of comprehensive and integrated community-based health care services, within the context of prioritizing promotive and preventative medicine [4].

The creation of homelands intensified the fragmentation of the country’s healthcare services, with dire consequences for the rural black population. It was through the 1960s and 1970s that such ‘black spots’ as popularly known by the historians, were created, namely: the ten homelands of which Venda, Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Ciskei became fully independent. The remaining six included: Lebowa, KwaZulu, Gazankulu, Qwaqwa, KaNgwane and KwaNdebele which remained self-governing states, with other departments still under the control of Central government. This arrangement was aiming at the eventual complete independence that would disprove all blacks from being citizens of the Republic of South Africa but of the respective homelands where they could practice their own political, social, cultural and economic affairs [5].

However, the homelands were unable to provide health services effectively because of meagre and insufficient allocated budged which was tightly controlled by the National Party government. The fact that the homelands were financially depending on the central government, made it impossible to effectively provide health services to their populations as the allocated budget was usually inefficient and tightly controlled. In order to remedy the situation, Gazankulu, Kwazulu and Bophuthatswana committed themselves to a community medicine approach based on preventative primary healthcare rather than purely hospital-based curative medicine. Further action was evident when in 1977 the Gazankulu government introduced a Five-Year Health Service Plan which was to be piloted in 18 health centres, with specific objective of providing comprehensive PHC services to everyone in the homeland. It became evident that this endeavour could not be easily achieved due to available insufficient funds [1].

The lack of funds was also felt in other homelands throughout the country as it happened in Bophuthatswana when in 1981 the report by a senior official revealed that 400 villages were without clinics. Similar incidents were reported by the head of the Department of Community Medicine of Natal Medical School. The report reflected that Kwazulu homeland could not manage to build additional 200 clinics due to insufficient budget allocated by the South African government [6].

Selina Maphorogo explained that the introduction of the 1977 Service Plan in Gazankulu was influenced by the promulgation of the 1977 Health Plan by the Nationalist government. She indicated that other homelands in South Africa were influenced by the Gazankulu Service Plan despite the South African government’s reluctance to effect meaningful health reforms for the rural blacks [7].

The role of the South African Defense Force was also crucial in the development of PHC services in the homelands since the 1970s. Since the South African Defense Force consisted of highly professional soldiers in a variety of fields, the soldier doctors were utilized to perform the necessary health services. This was made possible by the Army Education Scheme (AES) which was introduced in the army in 1939 to see to it that the servicemen are prepared for the war and post-war era to be in line with the concept of ‘war and peace’. It was the medical section of the South African Force which played a vital role in the community health development since 1945 as the incidents of diseases among blacks were escalating due to post-war economic constraints [1]. The military medical officers were mostly used where there were staff shortages. For example, when the officers of the health service from Pietersburg (Polokwane) visited several hospitals in Lebowa in 1978, they found that a military medical officer was left in charge of St. Ritas Hospital near Jane Furse in Sekhukhuneland while the Superintendent was on leave. At Metse-a-Bophelo the staff shortages were resolved with the addition of two military medical officers [8].

In Lebowa, Venda, KwaNdebele and Bophuthatswana as well as other areas where the majority of blacks resided, soldier doctors were sent to the schools, hospitals and clinics to perform health services to the needy as a result of a shortage of doctors and nurses. One should also note that although use of these soldier doctors was aimed at winning the support of black communities as the resistance against apartheid was showing an upward trend, nevertheless it helped greatly in the reduction of poverty and diseases. Their provision of food parcels, medicines, vaccinations, campaigns and other immunisation services was crucial [9].

The fragmentation of the homelands had a negative impact on the lives of the homeland population in relation to the provision of PHC services. This state of affairs became evident with regard to the scattered distribution of clinics and hospitals, which, in turn, impacted on the provision of PHC services. It is crucial to note that hospitals as health care centres, played a crucial role in the support and the provision of community-based healthcare services as well as to create a balance between curative and preventative healthcare services [5].

The regionalization process in the homelands aggravated challenges related to access and development of basic healthcare services. Hospitals remained crucial in the provision of basic healthcare services as doctors, nurses and other health practitioners were supposed to know the various health challenges as well as other related issues pertaining to social, cultural, economic and status of the surrounding population. It was in this respect that the homeland system was considered significant in the division of people in terms of ethnic groups, and by so doing, exacerbating incidents of unequal access to health services.

At Shiluvane Hospital, situated near Tzaneen in the eastern Transvaal represented a typical example of imbalance created by regionalization. The hospital was controlled by Lebowa government from 1976-1981 and was later handed over to Gazankulu homeland by the South African government. Such intervention created divisions as the area was inhabited by both the Pedi and Shangaan-speaking population. The frustration became evident when the Lebowa Department of Health established Dr C.N. Phatudi Hospital, about five kilometres north east of Shiluvane Hospital, a situation that compelled the Pedi hospital staff and patients to be transferred to the new hospital. The challenges that already existed in terms of community health service delivery were accelerated by such political divisions, thus hampering the expected positive implementation of PHC programmes already in place [10].

Similar situation occurred in the two districts, Mapulaneng and Mhala, situated side by side by the apartheid homeland system. For instance, Mhala belonged to Gazankulu homeland which inhabited the majority of the shangaan ethnic group, while Mapulaneng was given to Lebowa with the Sotho-speaking majority. The homeland policy in these two districts created many problems because it broke up health services and created divisions and social ills between the people. A study conducted by the Institute for Development Studies of the Rand Afrikaans University (University of Johannesburg) during the early 1980s at the Mhala revealed that the homeland had serious widespread of poverty and diseases associated with adversity of land, food, water, transport and education [10] (Figure 3).

Tintswalo Hospital was situated in the Mhala district of Gazankulu homeland while Masana was located in the Mapulaneng district of Lebowa as reflected on the above map. The geographical distribution of the two hospitals depicts how fragmentation impacted negatively on the provision of health services to communities. Before homelands were created there was a coordination and communication of services to all people in the region without ethnic segregation, but this scenario changed thereafter. Since the two homelands overlap and penetrated each other in terms of human settlement, confusion always existed as the Shangaan population, who happened to be located at proximity to Masana Hospital were frustrated when they had to travel long distances to Tintswalo Hospital situated in the north-eastern corner of the district bordering Mapulaneng district of Lebowa. On the other hand, the Pulana people of Lebowa experienced similar problem when they had to travel to Masana which was located far south of the district [10]. This scenario was complicated by the fact that these homelands followed different healthcare policies, leaving clinics in the area supporting communities belonging to the two different authorities, thus complicating the administration and management of both homeland departments of health.

The fragmentation in this respect also frustrated the system of home visits to the patients by the nurses and other health care teams to either side of the districts. The referral system of patients to the hospitals worsened and further complicated the provision of community health services. Mapulaneng and Tintswalo Hospitals represented a clear illustration of how the homeland system destabilised the intended ideas of PHC, which was seen as a viable way of solving a variety of health problems of rural blacks in the area [10].

The Politics of Early 1970s and Health Act 63 of 1977

Since the social organisation of South African medicine was mainly white-centred, the training of nurses and doctors was effected at different or separate institutions, which also created unequal provision of health services, finances, and other resources relative to health matters. This political norm became an inevitable breeding ground for unequal physical capacities, physical quality and quality of care offered by the state [10]. The opening of Durban Medical School in 1951 was aiming at the training of black students– Africans, Indians and coloureds, who were from different provinces of South Africa. Although the institution was segregated from the white medical students which had a separate campus, the medical degree offered to blacks was recognised on an equal basis, with those provided by the country’s white medical schools, and the degree also offered students to register with the South African Medical and Dental Council, which was responsible for the regulation of practice of medicine in South Africa. Most of the former students of the institution produced the most prominent leaders who played significant roles in the resistance against apartheid. Some of these leaders included: Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi, Professor Malegapuru William Makgoba, Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma, Dr. Frank Mdlaluse, Dr Mamphela Ramphele, and Dr Ben Ngubane [11]. Most of these leaders were afforded with leadership roles in the newly- formed democratic South Africa since 1994.

When the Medical University of South Africa (MEDUNSA) was established in the late 1970s, the idea of emphasising and strengthening community-based preventative PHC services continued to be seen as a workable model to overcome health challenges in tge rural and township areas. Meanwhile MEDUNSA was additional symbol of racially segregated health institution for blacks, its inception was also aimed to alleviate scarcity of black doctors with the hope of increasing black health professionals in health sciences [11].

Kathleen Dennil argued that the economic recession in the 1970s was also influential in the state’s move towards the direction of self-reliance and privatization of health to overcome financial challenges. A comprehensive approach, with preventative community- based health care was considered a priority by the state [12]. This became evident when the Health Act 63 of 1977 was promulgated with the aim of rationalizing health organizations and promoting community health care services by statutory means. It was in this respect that the state saw the need to emphasise preventative health care as well as the establishment of community health centres [1].

The idea received outstanding support from the Star Newspaper Science Editor, Marais Malan It was also during the second half of the 1970’s that Marais Malan, the Star Newspaper Science Editor who emphasized the importance of the preventative health rather than costly curative services that only catered for the few South Africans. Malan also remarked about the warning from an expert in the medical field. Professor I.W.F. Spencer who held the chair in comprehensive and community medicine at the University of Cape Town, and as a former deputy medical officer of health in Johannesburg who also supported the idea. Other related issues raised by Spencer included training of community members to adapt comprehensive care and organizing funds to cater for the needs of the rural areas due to their less access to the urban health services [13].

Although little was achieved in bringing about meaningful health reforms, the step taken in the promulgation Act 63 of 1977 was a clear indication that the pressure from the marginalised black people compelled the state to come to its senses. One would also argue that the state’s action in this regard was the beginning of its preparedness to embark on the road to health for all, even though it was doubtful as to whether it would abandon segregated health care in favour of unitary health for all races as a solution.

The State of Reluctance and Health Reforms of the 1980s

The health politics of the late 1970s and early 1980s were marked by emergence of hopes and uncertainty on matters related to health reforms in the country. This state of affairs was exacerbated by the growing popularity of global PHC concept since the inception of Alma Ata Conference of 1978. Among these professional formations were National Medical and Dental Association of South Africa (NAMDA) and other United Democratic/ANC-aligned health formations who put pressure on the state to address health challenges. The National Party’s new leadership under Prime Minister, PW Botha saw the need to reform apartheid instead of abolishing it completely by establishing various commissions to investigate the health challenges. At the same time there was a growing concern worldwide over escalating state of poverty, diseases and fragmentation of health services. In South Africa and elsewhere throughout the world, health professionals held robust discussions about need for implementation of progressive healthcare.

Among those fought to achieve equitable health services to all South Africans included the likes of Dr Aaron Motsoaledi, Dr Joe Phaahla and Dr Peter Kgaphola [14]. Leaders of South African Council of Churches like Father Smangaliso Mkhatshwa, Frank Chikane, Dean Farisani, Dean Mminele and Desmond Tutu also influenced the health reform initiatives [14]. In addition to these developments, the Azanian Peoples Organisation (AZAPO) responded fiercely against segregated healthcare services. The escalating discontents of fragmented segregated healthcare services in the homelands of Lebowa and Gazankulu as well as in other homelands in the country [15], compelled the state to pass various health legislations of which the National Health Plan of 1986 and the National Health Policy Council were significant [16].

The nationalist government was aware that health reforms were necessary, however they chose to delay the process in favour of apartheid throughout the period of the 1980s until 1994 when democratic government was entrenched. One can argue that this decision in a way intensified resistant activities, forcing the government to be on the defensive and negotiating under duress.

Conclusion

The notion of equalising health services for all South Africans created mounting pressure exerted against apartheid government by anti-apartheid organisation which forced the state to be on the defensive since 1948. The delaying tactics adopted by the state heightened tensions and tussles over the issue of segregated healthcare services until 1994 when democratic government was established. However, the health constraints created during apartheid era were carried into democracy, making it difficult for the state to fulfill the agenda of universal healthcare coverage for all South Africans, most particularly the previously disadvantaged rural black communities. These post-apartheid challenges included among others like shortage of medications, clinics, hospitals, doctors, nurses, health workers and other health-related requirements. When COVID-19 erupted in the country during the late 2019, it became difficult for democratic government to deal effectively with the disease. Government attempts to deal effectively with this pandemic was hampered by a variety of challenges associated with unresolved poor infrastructure, electricity load shedding, corruption and fraud, incompetent leadership, dysfunctional government institutions, illegal foreign nationals and soaring unemployment which continued to complicate health services. Many South Africans continue to rely heavily on government health institutions where health services remained poor as compared to the quality provided by expensive and unaffordable private health facilities.

The signing of the National Health Insurance (NHI) into law on 15 May 2024 by President Cyril Ramaphosa which aimed at implementing the long awaited quality and affordable health for all, received critical response from business sector and civil society organizations [17]. With many South Africans, most particularly rural blacks suffering from escalating disease crisis like HIV-AIDS, sugar diabetes, cancer, hypertension, glaucoma and cardio-vascular disease, it became evident that health challenges were far from being resolved. Disease burden continued to cause ill-health and mortality among black South Africans, with rural blacks as the most vulnerable victims because of high poverty rate. Although the recent Government of National Unity (GNU) created after 29 May 2024 general elections vowed to forge ahead with NHI implementation, some outstanding divides between the businesses and government delayed the process. The implication is that if amicable agreement is not reached, the matter might possibly take a costly legal route before it is fully implemented. The struggle for its full implementation remained a poignant reminder of the negative trait of the legacy of apartheid.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- De Beer C (1986) The South African Disease: Apartheid Health and Health Services. Johannesburg.

- Horwitz (2009) Health and Health Care under apartheid. University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- Marks S, N Andersson (1987) Issues in the Political Economy of Health in Southern Africa. J South Afr Stud 13(2): 177-186.

- Digby A (2012) The Bandwagon of Golden Opportunities’? Health in South Africa’s Bantustan Periphery. South African Historical Journal 64(4).

- Van Rensburg HCJ (1992) Health Care in South Africa: Structure and Dynamics. Academica, Pretoria.

- Van Rensburg HC Van J (2004) Health and Health Care in South Africa. Van Schaik, Pretoria.

- Maphorogo (2007) Elim Care Group Centre, Waterval, Louis Trichardt.

- (1978) Limpopo Provincial Archives, Box 21, File16/2, Medical and Preventative Medicine, The Visits to Lebowa Hospitals: pp. 1-3.

- Maepa MW, Personal experience as a former Lebowa Homeland citizen during the 1970s and 1980s.

- Buch E (1988) A National Health Service for South Africa Part 1: The Case for Change, The Centre for the Study of Health Policy, University of Witwatersrand. Johannesburg.

- Noble VA (1913) School of Struggle: Durban Medical School and the Education of Black Doctors. University of Kwa-Zulu Natal Press.

- Dennil K (1995) Aspects of Primary Health Care. Southern Book Publishers.

- (1976) Witwatersrand University Historical Archives, AD, Box 1912, File 112.19, Health, 77c The Star.

- Makgoga N (2017) Deputy Director, Limpopo Provincial Department of Health.

- Ramphele M (2013) Non-Governmental Organisation, Community Health, Tzaneen.

- (1994) Subcommittee: Primary Health Care Strategy for Primary Health Care in South Africa. Nursing RSA: pp.9-24.

- (2024) Department of Health. National Health Insurance: Access to health services you need, when and where you need them, without financial hardship. gov.za.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.