Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Biopesticides and Anaerobic Fermentation in Sustainable Agricultural Production in Nigerian Soils

*Corresponding author: Nweke IA, Department of Soil Science Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Nigeria.

Received: February 18, 2025; Published: March 20, 2025

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2025.26.003432

Abstract

The sustainability of crop production in Nigeria with much population increase and critical environmental challenges is very problematic. Intense rainfall and high temperatures experienced in the area create good conditions for various type of pathogens and pest to thrive and cause different kinds of diseases to crop plants. Thus, limiting production period for most crops in the area. Synthetic or chemical pesticides used to confront these disease problems have been found to have pronounced negative effects on the health of humans such as been carcinogenic, natural foe, poisonous to community of organisms in the soil and their interaction with the environment. While increased use of the synthetic pesticides has been found to cause disappearance of bees and some other useful insects responsible for pollination. Biopesticides proffers better substitute to chemical or industrial pesticides due to their less poison, degradability and very less lasting effect in the environment or an area applied. They are readily available and inexpensive, unlike the synthetic that has not been sustainable at the farmer’s level. Increased awareness of the public on the dangers pose by synthetic pesticides on the soil, safety and quality of food have hastened the use of biopesticides in agricultural production. This is very important for increased food production to checkmate the population increase as well as income generation and delivery of healthier food to the public.

Keywords: Aerobic, Anaerobic, Bioheat, Biopesticides, Fermentation, Organic Farming

Introduction

The sustainability of agricultural activities in Nigeria is herculean task as it faces a lot of challenges; the soils are fragile and prone to erosion and land degradation problems, population explosion that put pressure on available land that today some of the suitable land for crop production now play home to residential building, industries or even roads. Intense rainfall and temperature that have created different scenarios or situations in soil such as soil infertility, multiple nutrient deficiency, low soil biodiversity, moisture stress, disease organism, disease and pest infestation, toxic substances ecological imbalance etc. While inputs such as improved seeds and cultivars, synthetic pesticides, chemical fertilizer and other synthetic chemicals to confront these challenges are not within the reach of poor resource farmers that form the bulk of crop and food producers in Nigeria. Thus, the inputs whether in form of improved seeds and cultivars or synthetic chemicals has never been sustainable at the farmer’s level in Nigeria. In the works of Nweke, et al., (2018abc) [104,106-7] and Nweke, et al., (2020abc) [108-110] different ideas and solutions were proffered on how to meet up with most of the above challenges facing crop production in Nigeria using indigenous cultural practices. This particular paper again will try to x-ray the need for the farmers to anchor their knowledge, energy and resources to the use of our indigenous bio-pesticides for increased healthy growth of crops, yield and healthy food delivery to the populace. This is very important knowing fully well that most of these disease-causing agents and pests inhabit the soil, hence making them more difficult to control. Nematode for example inhabit the soil from where it attacks the underground part of the plant host making nutrient absorption, water uptake and all that dissolve therein impossible leading to the death of the plant. Pests and pathogens are capable of causing monumental damage to a wide range of crops, vegetables, cereals, grains, roots and tubers, flowers etc., making a farmer to be under penury. Sikora, et al., and Fernandez, et al., [118] found out that in tropical and subtropical agriculture nematode causes great losses in vegetable crops. Maize, one of the major crops cultivated across the globe, is susceptible to a lot of diseases and pests causing great yield decline and nightmares to the farmers. According to Flet, et al. (1996) [47] maize crops are attacked by nematode causing root-knot disease, viral disease such as streak and dwarf mosaic, cob and tassel fungal diseases, bacteria diseases like stalk rot and leaf streak and insect pest species such as aphids, leafhoppers, stalk borers, beetles, boll worms and weevils. Another important crop like cowpea have been noted by Adipola, et al. (1999) [3] and Edema (1995) [38] to be attacked by virus disease like anthracnose (rust virus) and scab, bacteria disease like blight and insect pest such as aphids, thrips, pod borers and foliage beetles.

The use of synthetic chemical in the control of diseases in crops is still a common practice in Nigeria and other and developing countries and even to some extent developed countries. The only difference is that in developed countries there is strict compliance to the type of synthetic chemicals that could be used for crop production. And even in sale of the farm produce a tag is placed on the produce to denote chemically produced or organically produced. In this situation the buyer is left with a choice of which product to buy. This is not obtainable in Nigeria and Africa at large. Although with the application of chemicals such as pesticides, fungicides, bactericides, nematicides etc., crop diseases can be managed but the consequences in ecosystem and human health are well documented. Pest resistance may occur with many applications. Chemical control of most pests and plant diseases may be present and could broadly decrease the effect of crop disease, but farm application of chemicals may not be worth the effort, an undesirable outcome. Gill, et al. (2012) [53] opined that the mysterious or sudden disappearance of bees and some other insects important in pollination of flowers of agricultural crops was due to increased use of chemical pesticides. While global decline in frog population as noted by Bruhl, et al. (2013) [20] may be associated with intensified use of pesticides. Elyous, et al., (2010) [40] in their studies observed that ground and surface water are contaminated, the ecosystem balance existing between soil-plant-microorganisms are very much disturbed with repeated application of various synthetic chemicals under intensive agricultural activities or production. The entire world has come to realize that undue and appropriate use of chemical is dangerous to the humans and animals’ health. Therefore, adequate study for environmentally safe and easily biodegradable biopesticides becomes the best alternative. According to Gnanamanickam, et al., (2002) [54], bio-pesticides are natural in origin and have less inauspicious effect on the physiology of crops and their processes of development and easily changed into environmentally friendly organic residues. For the following authors, Radhakrishnan (2010) [126], Akpheokhai, et al. (2012) [7] and Taye et al. (2012) [153], they are economical, biodegradable and bio-renewable resources. Biocontrol is the best option for disease and pest control in crop production and to cope with the dangers and losses at chemical control. Biopesticides can be derived or harnessed from microorganisms, plant parts or extracts and animals for pest and disease control. In order to encourage sustainable crop production Radhakrishnan (2010) [126] and Pendse, et al. (2013) [123] found biopesticides to be environmentally safe alternative for plant protection that have great potential for productivity. Extract from plants (such as oils, gums, resins etc.) according to Romanazzi et al. (2012) [131]; Jalili, et al. (2010) [69] and Fawzi, et al. (2009) [44] have been noted to exert great biological influence on plant fungal pathogens in vitro and can be used as biofungicidal products. These products are less hazardous for the ecosystems and hence alternative remedies for treatment of crop diseases Chuange, et al., (2007) [29]. Muthomi, et al. (2017) [97] found significant effective reduction against alternaria solani; Phythium ultinum, fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Lycopersici and rhzoctonia solani in vitro study involving alcohol plant extract of garlic (allium sativum), pepper (capsicum frutescens), turmeric (curcuma longa), ginger (zimgibar offcinals) and lemon (citrus limon), while turmeric was reported by the authors to be the highest with a growth inhibition of up to 73% relative to alternaria solani. In a study conducted at Igabariam southeast, Nigeria Chime et al. (2019ab) [26,27] observed an increased plant biomass of Indian spinach infected with root knot nematode in soils treated with ginger rhizome extract and pawpaw leaf. Their study showed the potential of ginger extract and pawpaw leaf as bio-pesticides against root knot nematode that normally attack the Indian spinach at early stage of growth in the study area. Taye, et al. (2012) [153] using plant extract and Elyous, et al. (2010) [40] using pseudomonas spp and plant extract found significant reduction in root knot nematode in tomato production. While Pascual, et al. (2002) [121] observed suppression of Pythiumultimum in crop plant in soils treated with municipal waste compost and its humic fraction. The biopesticides were able to affect these reductions because of their ability to stimulate the defence mechanism of the plant and their physiological processes that make treated crops more resistant to the diseases and pests. Another important aspect of these natural bio-pesticides, especially those applied inform of compost, is that they improved the physical, biological and chemical properties of the soil as can be found in the works of Randhawa, et al. (2001) [127], Pascual, et al. (2002) [121], Elyous, et al. (2010) [40], and Chime, et al. (2019ab) [26,27].

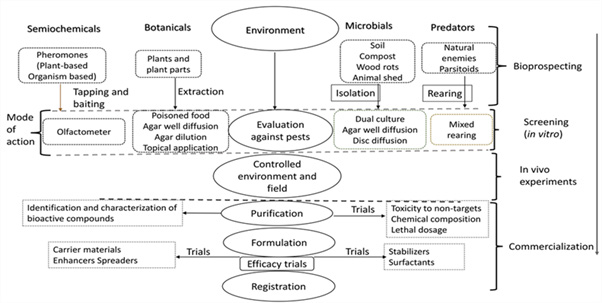

Bio-pesticides are an alternative to chemical pesticides due to their low toxicity, biodegradability and environmentally friendly. The base materials for bio-pesticides are available without much difficulty and at less cost. The formulation and commercialization of bio-pesticides, however, require the knowledge of their toxic levels, chemistry, active compounds and their compatibility with other methods of disease and pest management to achieve the desired results. The present study, therefore, aims to review and highlight the following:

a) the various sources of bio-pesticides.

b) their various active compounds or ingredients.

c) their components mode of action on targeted pests.

d) roles of bio-pesticides in sustainable agricultural production.

Materials and Methods

Materials used for this study were the various work done in the area of synthetic pesticides, bio-pesticides, bio-heat, anaerobic fermentation etc. These are published journal papers, books, seminar papers and student thesis and personal experience gathered. All were reviewed, discussed and draw conclusions from the results of the various practices.

Synthetic Chemicals and Bio-Pesticides at a Glance

Poisoning and toxicity as reported by Damalas, et al. (2015) [33] are some of the ills associated with synthetic pesticides use in crop production. Due to the non-degradability of their constituent compounds enhance environmental pollution Kekuda, et al., (2016) [76]. Most synthetic pesticides after application stay up to half a year in a soil environment before fully degraded and example of such as noted by Paliman (2001) [119] is the degradation of methane sodium. In the process of degradation pesticides become toxic and harmful to soil habitats (PAN, 2011). Following this, most synthetic chemicals like methyl bromide as a result of its toxic effects on the environment and crop production its use in agricultural activities have been banned. The chemicals can influence significantly the climate change because of its effect on ozone layer. The chemicals pollute the soil, ground water through leaching and make aquatic life and crop production impossible because the constituent makeup of the chemicals is toxic and take much time to degrade in soil Kumari, et al., (2014) [85]; Maksymiv, (2015) [90]. In agricultural production DDT (dichloro diphenl trichloro ethane) is no more in use due to its carcinogenic effects in humans as a result of retained active compounds in harvested crops and its poisonous effect to aquatic life (Jantasorn, et al., 2016 [70]; Harada, et al., 2016 [60]). Human population have been noted to be adversely affected by the application of these synthetic chemicals ranging from reproductive complications Ghorab, et al., (2015) [51]), retard growth and distort immune system and retard resistance of organisms to disease (Maksymiv, 2015 [90]), cause genetic mutations and damages and chronic diseases. Hence its use in crop production has generated much controversy with regards to its non-environmentally friendly status.

By-products and products of plants, microbes, insects and nematodes according to Gasic and Tavonic, (2013) [49] are bio-pesticides. Semeniuc, et al., (2017) [137] grouped the bio-pesticides into botanicals, resisters (obstructer), compost teas, growth promoters, predators and pheromones (secretion). Bio-pesticide active compounds are bound in plants and soil microbes of which include but not limited to saponins, alcohol, terpenes, phenols, quinones, alkaloids, and steroids (Nefzi, et al., 2016 [103]; Mizubuti, et al., 2007 [93]). Ali, et al. (2017) [10] and Vidyasagar et al. (2013) [154] observed that different plant species have various antimicrobial bioactive compounds like α- and β-phillandrene, limonene, camphor, linalool, and β-caryophyellene and linalyl acetate depending on the plant species. Kachhawa (2017) [73] enumerated microbial biopesticides to include bacteria species like Xanthomonas, Bacillus, Rahnella Pseudomonas, and fungi or Serratia such as Verticillium, Beauveria and Trichoderma, species. Souza et al. (2007) [6] reported that they exhibit different modes of action against disease causing pathogens. Plant growth, root hair formation and protection from environmental stress are improved by bacteria such as pseudomonas, bacillus, rhizobium, agrobacterium, ensifer, microbacterium, chryseobacteria and rhodococcus Souza, et al., 2015 [146]; Abbamondi, et al., (2016) [1]. These microbes as reported by Compant, et al. (2009) fix nitrogen, enhance phosphate solubilisation and increase crop yield. Esitken, et al. (2009) [42] reported increased yield, phosphorous, and zinc content in fruits and soil as well as plant growth when pseudomonas and bacillus are used as bio fertilizer. In management of destructive insects like Helicoverpa armigera (boll worm) in cotton plant, natural enemies such as insects, pathogens and predators, bugs, beetles, parasitoids, wasps, lady birds, compost tea extract etc. could be used as bio-pesticides Knutson, et al., (2015) [81]; Wu, et al., (2005) [157]; Ghorbani, et al., (2005) [52]).

Restrictions and Challenges in the Use of Conventional Pesticides

In eager to control destructive pests in farms farmers end up applying more synthetic chemicals than required through continuous application and this led to development of resistant pathogens and their rebirth Birech, et al., (2006 [18]; Halimatunsadiah, et al., (2016) [59]. Prasad, et al. (2010) [125] and Ndakidemi, et al. (2016) [102] argued that these chemicals disrupt organism biodiversity by killing antagonist, predators and pollinators of which are beneficial organisms. For example, it has been documented that some of these chemicals persist for many days even up to months in soil Xavier, et al., (2016) [158] and retention of their residues in crop products even after processing Pandey, et al., (2016) [116]. As a result of these aforementioned problems, crop production in developing countries is seriously affected to the extent that the European Union (EU) has put up strict regulations on agricultural produce entering their market from those developing countries with regards to level of pesticide residues. Hence from Business Daily, (2014) [22], it was found that EU banned the use of dimethoate containing pesticide in vegetable production and above limit led to destruction of fresh vegetable consignments. While Business Daily, (2013) [21], recorded that chemical residue should not exceed 0.02ppm on fresh vegetables and at port of entry to the EU should not exceed 10% on fresh produce. In related manner, unidentified synthetic chemicals, their Maximum Residue Levels (MRLs) must not be above 0.01mgkg-1, this they imposed 10% sampling check in fresh beans and pods per consignment European Commission, (2012). From the Business Daily, (2014) [23], it was found out that Kenya’s export market was almost ruined due to the traces of banned chemicals found on the fresh produce intended to export to EU. These restrictions, however, brought down the volumes of export of agricultural produce leading to losses and total rejection as well as destruction of the consignments. Daily Nation (2014) [31] noted that the entire scenario affected the livelihood of small holder farmers that are the main producers of vegetable crops. In order not to blanket the farmers and to pinpoint the farmer whose good fail the test regulation, GPS coordinates and quick reference code are used Daily Nation (2016) [32], as a result many farmers who cannot cope opted out of the business due to increase in the cost of production.

Sources of Bio-Pesticides and their Effect on Causative Agents

Bio-pesticides of plant origin: Botanical pesticides as noted by Vidyasagar, et al. (2013) [154] can be essential oils or plant extract, though it depends on the method of extraction. This plant extract could come from rhizomes, cloves, bulbs, seeds, or flowers, roots, fruits, leaves, barks, which are either dried or fresh. For instance, Chougule, et al. (2016) [28] observed that the extract from dried parts of plant is the ideal as this result in higher yield of active ingredient due to reduction in water concentration. The major oil component found in citrus sinensis using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis were mycene and d-limonene, Zarubova, et al. (2014) [161] reported that these products cause 48% mortality in larvae of cereal leaf beetle (Oulema melanopus) of wheat within 48 hours of application.

Nefzi, et al. (2016) [103] worked on aqueous fruit extract of Withania somnifera and using merely a concentration of 2% found 56% growth inhibition of the fungal pathogen (Fusarium oxysporum F.SP. radicis-lycopersici) of root not disease in tomato and crow. Also, in research conducted by Muthomi, et al. (2017) [97] using ethanol extracted from crops such as lemon (Citrus limon), ginger (Zingiber officinale), pepper (Capsicum frutescens) garlic (Allium sativum), and turmeric (Curcuma longa), found out that extract from turmeric greatly limit the growth of Alternaria solani and Pseudomonas syringae p.v up to 73%. Using in vitro technique in tomato Bastas, (2015) [16], found the crop efficiently managed by Rosmarinus, Eucalyptus globulus and officinalis Rhus coriaria. He found under greenhouse research that Eucalyptus globulus effectively cause 65% reduction on Pseudominas syringae p.v. (bacterial speck of tomato). A mortality rate of 78% on juvenile of root not nematodes (Meloidogyne sp) by extracts of Nerium oleander was reported when the concentration increased to 5%. On the second stage application of 10% a mortality rate of 65-100% was recorded by Salim, et al. (2016) [134] on juveniles treated with extracts of Azadirachta indica, Zingiber officinale Eucalyptus sp, Nerium oleander, Cinnamomum verum, and Allium sativum. According to the work of Dar, et al. (2014) [34] the most commercialized botanical pesticides are extracts from sabadilla (Schoenocaulon officinale), neem (Azadirachta indica), pyrethrum (Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium), and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum).

Though the quality of oils and extracts as noted by Odhiambo, et al. (2011) [83] is dependent on two factors which are method of extraction and solvent used. Javaid, et al. (2011) [71] argued that extract that will possess preservative properties should be made from solvent of low toxicity, low temperature, evaporation easily and above all high dissolution percentage for many compounds. Although the choice of solvent is a factor of target active compound. Water is a universal solvent but according to Bandor, et al. (2013) [14] it extracts small antimicrobial compounds relative to other solvents. Ethanol and methanol solvents give better extracts, and their results have been found to be consistent. Other solvents according to the work of Mahlo, et al. (2013) [89], include hexane, acetone and dichloromethane. An extract of hexane and methanol obtained from Tarchonanthus camphoratus was observed by Wetungu et al. (2014) [156] to show much greater growth prevention against salmonella typhi, Escherichia coli, Staphylocccus aureus, Candida albicans, Proteus mirabilis and Klebsiella pneumoniae. To extract seed component of Morinda citrofolia, methanol was found to be very effective and using the extract, Sunder, et al. (2011) [151] reported 63% antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas spp. Hence the differences recorded among the different solvents according to Ahmad, et al. (2009) [5] could be attributed to their different polarity. Thus, plant parts from which the extracts are produced affect the quality of the extracts.

Microbes as Source of Biopesticides

Most of the commercialized biopesticides are microorganism based on which are reported by Koul, (2011) [83] to include viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa and nematodes. Singh, (2014) [144] opined that biopesticides have been used in the management of insects, pathogens, nematodes and weeds, from the 175 reported microbial based biopesticide active compounds. Many of these biopesticides are used to control soil borne diseases as reported by Vinale, et al. (2008) [155]. Some bacteria species like Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Xanthomonas, Enterobacter, Streptomyces, Serratia noted to be either crystalliferous, facultative or obligate have been utilized as biopesticides. Fungi species used as biopesticides as reported by Kachhawa, (2017) [73], include Pythium, Penicillium and Verticillium., Trichoderma, Beauveria, Metarhizium, Paecilomyces, Fusarium, while nematode species used to produce biopesticides include Steinernama and Heterarhabditis. The mode of action of these microbes against pathogen as reported by Suprapta, (2012) [152] includes parasitism, hype-parasitism, competition, antibiosis and secretion of volatile compounds. Song, et al. (2012) [145] is of the opinion that the pesticides very active on agricultural fields are mainly sourced from microorganisms especially where they co-exist with other microorganisms. The rhizosphere is inhabited by many important classes of microorganisms. Other rich sources of microorganisms as reported by Beric, et al. (2012) [60] include manure, hay, straw and cow shed. The effectiveness of microbial biopesticides, however, depends on the formulation and substrate used. A study done by Adan et al. (2015) [2]indicated that black gram bran, peat soil and water used in the formulation of Trichoderma harzianum, showed greatest level of activity against Sclerotium rolfsii that cause damping off in eggplant seedlings. They attributed their findings to the high number of spores produced by the fungus.

The exposure of Helicoverpa armigera to conidial suspension of Beauveria bassiana, was observed by Prasad and Syed (2010) [125] to cause blackening of the body, sluggish and morbid in larvae and anti-feeding. Finally, death results when fungus consumes the entire larvae tissues. For instance, isolates of Bacillus showed antagonistic activity against rice pathogen, Xanthomonas oryzae P.V. oryzae, and Beric et al. (2012) [17], attributed the activity to the production of a bacteriocin by the bacterium. The effect of wheat rust (Puccinia recondite) and rice blast (Magnaporthe grisea) was found to have reduced up 80% when Park et al. (2005) [118] treated wheat and rice plants with concentrations of Chaetomium globosum. Their studies also showed that 50% reduction in late blight (Phytophthora infestans) on tomato was observed when Chaetomium globosum was used and in well diffusion assays mycelia growth of pythium ultimum was inhibited in vitro. Park, et al. (2005) [118] noted that the activity of the fungus was due to the production of two types of chaetoviridins, A and B. This documented evidence simply suggests that the microbial biopesticides can be integrated in pest management programmed for sustainable agriculture.

Biopesticides as Parasitoids and Predators

While parasitoids grow on or inside their hosts and eventually kill them, predator kills and feeds on their prey Elzinga, et al., (2002) [41]. According to Knutson, et al. (2015) [81] parasitoids consist mainly of wasps and other hemipterans, while predators are spiders, true bugs, beetles (Carabidae), ladybirds (Coccinellidae), and lacewings (Chrysopidae) etc. However, they are not evenly distributed in the environment where they are found. Hence in order to have them in large numbers Morales-Ramos, et al. (2014) [94] opined that they are either multiplied in the open field containing the prey or they are reared in a controlled condition such as green house and released into the fields. And the most ideal of rearing these predators is by growing them on their preferred host. Silva, et al. (2010) [146], noted that it is either grown under control condition or growth chambers where the host plants are first grown and then exposed to pest infestation and maintained by growing on the prey Lee, et al., (1990) [87]. In contrast, the predators can be reared in cylinders where they are provided with the prey and all other necessary conditions for growth are supplied. An example according to Morales-Ramos, et al. (2014) [94] is the mass rearing of Phytoseiulus persililis on Tetranychus urticae Koch. The optimum growth of Neoseiulus californicus, (predator mite) was observed by Khanamani, et al. (2017) [79] when grown on an artificial diet supplemented with eggs of Ephestia kuehniella, Artemia franciscana cysts and maize bran. Such artificial diets are important in reproduction, growth and survival of the predators during rearing and reduction in production costs. On the egg masses of their prey predators can also be grown on other suitable hosts that will give them longer storage capacity. Steinberg, (2013) [148] employed parasitoids in the management of mealy bugs. For Fernando, et al. (2006) [45] predators can be grown in rice bran because it contains nutrients necessary for the insects. However, considering the cost involved these predators are best reared in artificial media with carefully evaluated nutritional needs and requirements. Their growth media was found to range from beef and live to crushed lepidopteran pupae. This according to Grenier, (2012) [57] provides a combination of hormones and nutrients needed by the predators for growth and development. Artificial media is mostly used in laboratories and provide sufficient nutrients as the host plants thus reducing the cost of growing the plants. This technology has been used by Grenier (2009) [56] in rearing Trichogramma and Anastatus spp. In vitro study showed that Amblyseius swirskii predated on Tetranychus urticae nymphs and Frankliniella occidentalis Xu and Enkegaard, (2010) [160] of which their preference was their first instars. They found the predation rate on T. urticae to be 4-6 nymphs in 12 hours. The authors finally argued that predation is very much dependent on the traits of the host plant. Fiedler (2012) [46] reported a mortality rate of up to 86% in a synergistic effect on predation between Amblyseius swirskii and Phytoseiulus persimilis against two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae). He further observed that under laboratory conditions that a mortality rate of up to 72% within 25 days was achieved in introduction of Amblyseius californicus and Amblyseius degenerans into a population of Tetranychus urticae.

Formulation, Production and Commercialization of Biopesticides

Plants and plant parts obtained from the environment, natural or man-made according to Dubey, et al. (2016) [37] can be used to prepare botanical pesticides. To obtain extracts or essential oils according to Goufo, et al. (2008) [55], the materials should be cleaned of dirt and foreign materials, then extracted using distillation or solvent. The disc diffusion, agar well diffusion, agar dilution and poisoned food technique according to Ademe, et al. (2013) [4] and Jahangiriana, et al. (2013) [68] are then used to subject the resultant extracts to screening activity in vitro against pests. Field conditions is used to evaluate the most efficient and active botanicals in managing pests. While the active constituents of the selected extracts according to Nashwa, et al. (2012) [100] are then known or established for optimum formulation. Intensive laboratory research and field trials conditions are carried out to ensure that the most efficient combination of the active compounds, carrier materials, emulsifiers, surfactants and other components used in pesticide development are optimized. The report of the effectiveness from the laboratory and field trials is used to request for registration of the product from the pest control products body.

The process of producing microbial pesticides follows the same process as botanicals except that Hassanein, et al. (2010) [61] emphasized that the antagonistic microorganisms are obtained from sources like the compost, manure cowshed, hay fields, rhizosphere, etc. Sahu, et al. (2014) [132] stated that these organisms can be isolated in laboratory from pure culture and kept in good condition in agar slants. The effectiveness of trials in vitro according to Karimi, et al. (2012) [74] lies in such methods as agar well diffusion, agar discs’ diffusion and dual culture. However, Naing, et al. (2013) [99] said that to stabilize these organisms for field application they need to be multiplied in suitable substrate in laboratory, mixed with suitable and adequate carrier materials that will enhance application. In this process the efficacy trials of the natural products continue both in the laboratory and field conditions against the target pest before registration process begins and finally commercialization of the natural product. Nonetheless, many methods are used to assess the efficacy of the products these methods according to Hossain, et al. (2013) [62] and Araújo, et al. (2014) [12] were Gas Chromatography- Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). For longevity and to enhance their applicability the carrier materials and stabilizers are usually added to the active compounds. Thus, to increase their efficacy and applicability, formulation of the active compound should improve the stability of the product, this should also decrease its degradability from such factors as water, acids and heat. To achieve the stability of the product the carrier materials mainly used are clay, water, talc, petroleum distillates and corn starch. Also, during formulation of the compound emulsifiers such as soap is added to optimize the product and ensure that the effectiveness is not lost. The biopesticide of plant and microorganisms’ origin noted by Khater, (2012) [80] and Cawoy, et al. (2011) [24] respectively to have been formulated and commercialized for agricultural use include neem and pyrethrum, Bacillus and Trichoderma respectively.

Actions of Biopesticides

Biopesticides varied in their mode of action as the action is dependent on the type of the pesticide. Predation, antibiosis, antagonism, and hyper-parasitism are modes of action of microbial pesticides on pathogen. While botanical pesticides in their action against pathogens inhibit their growth by modifying their cellular structures, morphology and exhibit neurotoxicity in insects. Botanicals as well suppress, oviposition and repel insects. In the case of predators, they kill their prey by injection of toxic substances that finally kill the prey or by parasitization. Semi chemicals, however, can be used to attract the target pests, then through sterilization and death they can now be managed and their impact drastically reduced. Vidyasagar, et al. (2013) [154] found that extracts of plant from Asteraceae family inhibit hyphal growth and induce structural modifications on mycelia of plant pathogenic fungi. The absolute fungal toxicity was found to be due to the fact that extracts from the plant contain active compounds like; alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, and coumarins. According to Iberê, et al. (2014) [64] some compounds cause changes in the morphology of cellular organelles and cell wall. However, in some cases active compounds cause breakdown of fungal cell membranes there by making them permeable that will result in leakages of cell contents. El-Wakeil, (2013) [39] observe that plant bioactive compound cause separation of the cytoplasmic membrane and eventually death because it damages the intracellular components and swelling of cells. Phenolics and terpenoids build hydrophobic and ionic bonds and Rodino, et al. (2012) [130] noted that this can attack multiple proteins in the insects causing physiological malfunction. Compounds in plant extracts and essential oils interfere with receptor cells and this cause malfunctioning of the nervous system and failure of coordination cause death of the insect as reported by Moreira, et al. (2007) [95]./

Hyper- parasitism according to Akrami, et al. (2011) [8] is the most reported mode of action of many biocontrol measures or agents. The antagonist attacks the sclerotia or the hypha of the fungal pathogen, while some kills the pathogen or its propagules. A single pathogen as reported by Blaszczyk, et al. (2014) [19] can be attacked by a number of biocontrol agents. An example of parasitic biocontrol agent is Pasteuria penetrans according to Kokalis-Burelle, (2015) [82] it parasitizes on root-knot nematodes of Meloidogyne spp. Some form of Trichoderma species displays a predation style of action by releasing enzymes that directly kill cell walls of the pathogens and colonize the environment therein. Some microorganisms release some compounds that kill other microorganisms. This mechanism is called antibiosis and is mainly common with bacteria species such as agrobacterium, bacillus, burkholderia, pantoea, pseudomonas. Mendoza, et al. (2015) [91] reported antibiosis in the fungus Trichoderma spp. To enhance or fortify biocontrol, adequate quantities of antibiotics need to be produced. Pal, et al. (2006) [115] observed that bacillus cereus produces multiple compounds that could suppress more than two pathogens that are very effective in plant disease management programme. While Xiao, et al. (2011) [159] reported that Lysobacter and Myxobacteria produce lytic enzymes which hydrolyse compounds leading to suppression of pathogens. Beauveria bassiana prevents chitin growth and development in insects by conidia attaching to the insect’s body. Prasad, et al. (2010) [125] noted that the hypha penetrates through the cuticle after germination and grows throughout the insect body and finally killing the insect. Female sex pheromones (semi chemicals) are used to attract male insect pests, thus sterilizing them thereby reducing their effectiveness. So, when the sterilize male mate with the female insects the females lay unfertilized eggs thereby decreasing insect populations and their harmful effect (Refki, et al., 2016) [129]. Chermiti, et al. (2012) [25] however, reported that host site pheromones attract insects into site with mass traps from where they can be starved to death or sterilized. Predators feed on a particular life stage of their prey such as nymphs or larvae Xu, et al., (2010) [160]. The predator prey ratio is of importance in checking the populations of the pests and biodiversity Rao, et al., (2017) [128].

Efficiency of Different Kinds of Biopesticides

In managing crop pests’ chemical pesticides according to Khan, et al. (2015) [78] are considered more effective than biopesticides. Their efficacy and efficiency sometime as agued by Ahmad, et al. (2007) [6] are not very significantly effective to manage a particular population compared with biopesticides. When biopesticides are applied in the appropriate concentrations and frequencies, they perform better than chemical pesticides Shah, et al., (2013) [139]. Documented works across the world have shown different microorganisms, predators and plants with potential biopesticides properties, while natural enemies predate on insect pests. This helps to balance their population in the ecosystem. These kinds of predators according to works of Rao, et al. (2017) [128] and Kenis, et al. (2017) [77] are very important in crop management programme. These predators attract their insect prey through scents and attractants. An example of these scents’ pheromones has been commercialized as reported by Refki, et al. (2016) [129] and used in plant pests’ management like Tuta absoluta. While Galko, et al. (2016) [48] noted that commercialized pheromones are baited to help the adult insects and deactivating them by sterilization or starvation to death. Rizvi, et al. (2016) [129] in effort to manage different crops in their works found out that some plants contain certain active compounds that protect them from pest attack and these active compounds has been explored by researchers and found effective against several pests including nematodes and fungi Hussain, et al., (2015) [78]; Sidhu, et al., (2017) [141]. While some certain species of microorganisms have antagonistic properties towards other species hence effective as biopesticides Aw, et al., (2017) [13].

Extracts of some certain plants (neem Azadirachta indica and Mexican sunflower Tithonia diversifolia) have been observed to prevent growth of some diseases causing organism in some crops up to 100%. Ngegba, et al. (2018) [106] observed this effect in rotting disease pathogens of tomato, Aspergillus niger, Fusarium oxysporum and Geotrichum candidium. In a dose dependent poisoned food method research Patrice, et al. (2017) [122] used the extract of castor seeds (Ricinus communis) to prevent the development of post-harvest pathogens Penicillium oxalicum and Aspergillus niger of yams (Dioscorea alata). While Nweke and Chukwuma (2023) [111] in their studies used neem leaves and castor capsules to reduce fungal infection in tomato production. Also using extracts from Lasonia ineruis and Duranta erecta, Devi et al. (2017) [35] reported similar result on post-harvest pathogens like Rhizopus arrhizus, Sclerotium rolfsii and Fusarium solani. Minz, et al. (2012) [92] using methanolic extracts of Chenopodium ambrosioides obtained up to 50% inhibition of antifungal activity against Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. ciceris that cause wilt in chickpea (Cicer arietinum). Sumitra, et al. (2014) [150] in their own experiment recorded 70% - 80% control when they evaluated the efficacy of a biopesticide formulation that contains onion (Allium cepa) and ginger (Zingiber officinale) against tomato fruit worm (Helicoverpa armigera). They further reported an increase in yield of treated plants relative to the untreated ones. Powder extract of Solanum delaguense and Lippia javanica was used by Muzemu et al. (2011) [98] in their work to record 50% decrease in tomato red spider mites (Tetranychus evansi) and rape aphids (Brevicoryne brassicae) infestation. Extracts of henge (Ferula assa-foetida), Allium sativum and Curcuma longa, were used effectively by Shah et al. (2013) [139] to decrease the population of larvae and pupa of Helicoverpa armigera. While a mortality of 60% - 100% of green peach aphid (Myzus persicae) was recorded by Nia, et al. (2015) [105] within one-day exposure in dose dependent in vitro experiments using extract from, Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Rosmarinus officinalis and Artemisia herbaalba soaked on leaves of broad bean. In similar study Part, et al. (2015) [120] recorded 100% mortality rate of bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) within less than 19 seconds exposure to the extract of Annona squamosal, Ficus benghalensis, Polyalthia longifolia, Azadirachta indica and Mangifera indica.

The effectiveness of plant extracts on insects as recorded by Oyedokun, et al. (2011) [114] and Barbosa, et al. (2013) [15] depends on the type of solvent and its ability to extract the main active compound with insecticidal properties. Karimi, et al. (2012) [74] reported an increase in plant growth parameters when they evaluated seed treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pseudomonas putida and Bacillus subtilis, against Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. ciceris. Beric, et al. (2012) [17] and Islam, et al. (2012) [65] earlier reported that some certain species of bacillus release some active compounds effective against some fungal pathogens such as Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae and Rhizoctonia solani. Extract from Chaetomium globosum have also been reported by Park, et al. (2005) [118] to be effective against fungal pathogens of rice (Magnaporthe grisea and Puccinia recondita). The effect of fusarium wilt of tomato was found reduced by Anitha and Rabeethet al. (2009) [11] after using streptomycesgriseus extract. In a seeded media study, Selim, et al. (2016) [136] found Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Stenotrophomnas maltophilia, to have exhibited antagonism effect against Erwinina carotovora. Extract from poultry litter and compost tea decrease the seriousness of bacterial wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum) of brinjals (Solanum melongena) as recorded by Islam, et al. (2012) [65]. Greater efficiency was recorded when the extract from compost tea was used as a soil submerge and the poultry litter applied on the soil improved yield and health of plants. A similar formulation was found by Islam, et al. (2013) [66] to have decreased the frequency and seriousness of late blight (Phytophtora infestans) of potato (Solanum tuberosum) when the extract of compost tea was applied as a foliar spray. A formulation of compost tea containing wood chips when applied as a foliar spray by Pane et al. (2014) [117] was found to improve yield of Kohlrabi or German turnip (Brassica oleracea var. gongylodes) and lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. gentilina). Semiochemicals have been employed in management of insect pests, Chermiti and Abbes (2012) [25], found mass trapping by use of sex pheromones with water traps effective in management of Tuta absoluta by delaying their attacks on tomato plants. Similarly, Sarles, et al. (2015) [135] have used semiochemicals such as oviposition, sex pheromones, mating pheromones and host location to managed fruit flies (Rhagoletis cingulata). These semi chemicals according to the findings of Powell and Pickett (2003) [124] may be insect induced, or insect plant induced but whichever increased the reduction of the insect population infestation. Further, microbial nature and predator insects have been effectively used in insect pests’ management programme in crop production. For example, Xu, et al. (2010) [160] and Arthurs, et al. (2009) [11] have used species of Amblyseius swirskii in their studies to effectively manage spider mites (Tetranychus urticae), thrips, Scirtothrips dorsalis and Frankliniella occidentalis.

The role of Biopesticides in Sustainable Crop Production

The use of biopesticides in the management of crop pest was studied and found very effective by Birech, et al. (2006) [18] as synthetic pesticide in pest management. They are not only efficient in pest management but easily degradable in the environment, hence they are eco-friendly and do not pollute the environment Leng, et al., (2011). Following the demand for organically produced food world over biopesticides have become suitable alternatives to chemical pesticides Okunlola, et al., (2014) [113]. As reported by Khater, (2012) [80] they are safe to use on fresh fruits and vegetables because they have very short prey harvest intervals. Their action as well does not interfere with the beneficial organisms or natural enemies as they are target specific Shiberu, et al., (2016) [140]. According to Nawaz, et al. (2016) [101] the application of these biopesticides, even small quantity enhances pest management and promotes sustainable crop production. Biopesticides are safe products both for the field application and the user because of no toxicity Damalas, et al., (2015) [33]. Thus, biopesticides can suitably be integrated into pest management programmed to aid decrease the quantity of synthetic pesticides used in crop pests’ management Sesan, et al., (2015) [138]. Biopesticides through the introduction of vital microbial species could be used in removal of contaminants from agricultural soils Javaid, et al., (2016) [72]. They are found within the environment, hence inexpensive and easily available as some of them are used as food and feed Srijita, (2015) [147]. Natural products decompose quickly Kawalekar, (2013) [75] hence safe for use in the environment. Pesticides from natural sources according to Stoneman, (2010) [149] have very short re-entry intervals which guarantee safety for the applicant.

Disadvantages in use of Biopesticides

The advantages in the use of biopesticides in the management of crop pests are notwithstanding, there are some drawbacks in their full adoption as management options in pest and disease in agricultural fields. For instance, under field conditions for maximum efficiency high rates of the constituent compounds are needed as reported by Shiberu, et al. (2016) [140]. Though, Ghorbani, et al. (2005) [52] opined that the strength of the bioactive compounds in plants is controlled by the environment under which they grow. They are equally controlled by the diversity of plants and their species (Sales, et al., 2016) [133] leading to differences in the responses to pathogens. According to Sesan, et al. (2015) [138] method of extraction also influe influences the quality of botanical extracts. Also, it is difficult sometimes to get the right proportions of the active and inert ingredients needed during the formulation. Additionally, there is no standard preparation technique and procedure for effective testing, especially under field conditions as reported by Okunlola, et al. (2014) [113]. Although the in vitro technique gives wonderful results, there are always non-uniformity of results at the field probable due to low shelf life, poor quality of source materials and preparation methods. For predatory nature of biopesticides to be adopted Gerson, (2014) [50] noted that they need a lot of host crops and dispersal capability, while Lanzoni, et al. (2017) [86] is of the opinion that since their application may be manual, the exposure time and crop coverage is important because to cover small hectare could be very expensive.

Further, registration of the products according to Gupta, et al. (2010) [58] requires data on formulation, chemistry, toxicity and packaging and this is not easily available. Stoneman, (2010) [149] asserted that the cost of producing a new pesticide product is always high and has lot of setbacks in resource materials and non-readily available markets constitute the greatest limitation in investing in biopesticides. In developing countries inadequate facilities and money for the production of biopesticides limit investment in biopesticides. Many factors determine the shelf life of natural products some of these factors according to Koul, (2011) [83] are moisture and temperature that are many times difficult to control. Biopesticides face much competition from chemical pesticides and if produced for a small field, the costs will be high and not reachable to poor resource farmers. There is not much awareness with regard to biopesticides among the local farmers, stake holders and policy makers in agriculture. For microbial pesticides, Kumar, et al. (2015) [84] noted that there is no trust in the value and use chain between producers, buyers and users and considering the risk of importation, synthetic pesticides appear reliable (Figure 1).

Conclusion

Biopesticides remain a suitable alternative to chemical pesticides not minding the challenges facing the adoption. Stable products under field conditions will ensure the efficacy of biopesticides in plant disease/ pest management. Hence researchers should work together with experts in the industry and government as well as farmers that will be the end user to provide stable, durable and endurable formulations of biopesticides.

Acknowledgement

We are greatly indebted to our students of whom their research assignments and seminar papers form the basis of this work. We wish to express our thanks and appreciation to all the farmers we consulted and interviewed who gave us much incite on their findings with regard to the use of biopesticides in crop production.

References

- Abbamondi GR, Giuseppina T, Nele W, Sofie T, Wouter S et al. (2016) Plant Growth-Promoting Effects of Rhizospheric and Endophytic Bacteria Associated with Different Tomato Cultivars and New Tomato Hybrids. Chem Biol Tech Agric, 1: 1-10.

- Adan MJ, Baque MA, Rahman MM, Islam M, Jahan A et al. (2015) Formulation of Trichoderma Based Biopesticide for Controlling Damping off Pathogen of Eggplant Seedling. Universal J Agric Res, 3: 106-113.

- Adipala E, Omongo CA, Sabiti A, Obou JE, Edema R, Bua B et al. (1999) Pests and diseases on cowpea in Uganda experience from diagnostic survey. African Crop Sci J 4: 465-478

- Ademe A, Ayalew A, Woldetsadik K (2013) Evaluation of Antifungal Activity of Plant Extracts against Papaya Anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides). Pl Path Microbiol 10: 1-4.

- Ahmad A, Alkarkhi AFM, Hena S, Lim HK (2009) Extraction, Separation and Identification of Chemical Ingredients of Elephantopus scaber L. Using Factorial Design of Experiment. Inter J Chem 1: 36-49.

- Ahmad S, Khan IA, Hussain Z, Shah SIA, Ahmad M, et al. (2007) Comparison of a Biopesticide with Some Synthetic Pesticides against Aphids in Rapeseed Crop. Sahrad J Agric 4: 1117-1120.

- Akpheokhai IL, Cole AC, Fawole B (2012) Evaluation of some plant extracts for the management of Meloidogyneincognita on soybean (Glycine max). World J Agric Sci 8(4): 429-435.

- Akrami M, Golzary H, Ahmadzadeh M (2011) Evaluation of Different Combinations of Trichoderma Species for Controlling Fusarium Rot of Lentil. Afr J Biotech 14: 2653-2658.

- Alavanja MCR, Ross MK, Bonner MR (2013) Increased Cancer Burden among Pesticide Applicators and others Due to Pesticide Exposure. A Cancer J Clinic 63(2): 120-142.

- Ali AM, Mohamed DS, Shaurub EH, Elsayed AM (2017) Antifeedant Activity and Some Biochemical Effects of Garlic and Lemon Essential Oils on Spodoptera littoralis (Boisduval) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J Entom Zool Stud 3: 1476-1482.

- Anitha A, Rabeeth M (2009) Control of Fusarium Wilt by Bioformulation of Streptomyces griseus in the Green House Condition. Afr J Basic Appl Sci 1-2: 9-14.

- Araújo KM, Lima A, Silva JN, Rodrigues LL, Amorim et al. (2014) Identification of Phenolic Compounds and Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Euphorbia tirucalli L. Antioxid 3(1): 159-175.

- Aw KMS, Hue SM (2017) Mode of Infection of Metarhizium spp. Fungus and Their Potential as Biological Control Agents. J Fungi 3(2): 30.

- Bandor H, Hijazi A, Rammal H, Hachem A, Saad Z et al. (2013) Techniques for the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Labanese Urtica diotica. Amer J Phytomed.Clinic Therapeut 6: 507-513.

- Barbosa FS, Leite GLD, Martins ER, Davila VA, Cerqueira VM et al. (2013) Medicinal Plant extracts on the Control of Diabrotica speciosa (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Brazil J Med Pl 1: 142-149.

- Bastas KK (2015) Determination of Antibacterial Efficacies of Plant Extracts on Tomato Bacterial Speck Disease. J Turk Phytopath 1(3):1-10.

- Beric T, Koji M, Stankovi S, Topisirovi L, Degrassi G et al. (2012) Antimicrobial Activity of Bacillus spp. Natural Isolates and their Potential use in the Biocontrol of Phytopathogenic Bacteria. Food Techn Biotech 1: 25-31.

- Birech R, Bernhard F, Joseph M (2006) Towards Reducing Synthetic Pesticides Imports in Favour of Locally Available Botanicals in Kenya. Proceedings International Agricultural Research for Development Bonn 8-12.

- Blaszczyk L, Siwulski M, Sobieralski K, Lisiecka J, Jedryczka M et al. (2014) Trichoderma spp. Application and Prospects for Use in Organic Farming and Industry. J Pl Protect Res 4: 309-317.

- Brühl CA, Schmidt T, Pieper S, Alscher A (2013) Terrestrial pesticide exposure of amphibians: An underestimated cause of global decline? Sci Rep 3: 1135

- (2013) Chemical Ban Hits Vegetable Exports to the EU Market. Business Daily.

- (2014) Illegal Horticulture Exports Risk Kenya’s EU Market. Business Daily.

- (2014) Regulator Suspends Use of Pesticides on Vegetables. Business Daily.

- Cawoy H, Wagner B, Fickers P, Ongena M (2011) Bacillus-Based Biological Control of Plant Diseases, Pesticides in the Modern World, Pesticides Use and Management 2011, Margarita Stoytcheva (Ed.).

- Chermiti B, Abbes K (2012) Comparison of Pheromone Lures Used in Mass Trapping to Control the Tomato Leafminer Tuta absoluta in Industrial Tomato Crops in Kairouan (Tunisia). EPPO Bulletin 241-248.

- Chime EU, Nweke IA, Ibeh CU, Nsoanya LN (2019a) Biopesticide and biofertilizer effect on some growth parameter of indian spinach and soil physical properties Inter. J Inform Res Rev 10(1): 6051-6054

- Chime EU, Ibeh CU, Nweke IA, Nsoanya LN (2019b) Bioefficacy of some biopesticide agents and treated pennisetum biofertilizer against root- knot nematode (meloidogyne incognita) on Indian spinach (basellaalba) and soil chemical properties Inter. J Inform Res Rev 10(1): 6047-6050

- Chougule PM, Andoji YS (2016) Antifungal Activity of Some Common Medicinal Plant Extracts against Soil Borne Phytopathogenic Fungi Fusarium oxysporum Causing Wilt of Tomato. Inter J Dev Res 3: 7030-7033.

- Chuang PH, Lee CW, Chou JY, Murugan M, Shieh BJ et al. (2007) Antifungal activity of crude extracts and essential oil of Moringa oleifera Lam. Biores Techn 98(1): 232-236.

- Compant S, Clément C, Sessitsch A (2009) Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria in the Rhizo- and Endosphere of Plants: Their Role, Colonization, Mechanisms involved and Prospects for Utilization. Soil Biol Biochem 42: 669-678.

- Daily Nation (2014) Bio-Pesticides in Focus as Safety Concerns Reshape Export Trade.

- Daily Nation (2016) Boost for Horticulture as New System Set to Improve Quality.

- Damalas CA, Koutroubas SD (20156) Farmers’ Exposure to Pesticides: Toxicity Types and Ways of Prevention. Toxics 8(1): 1.

- Dar AS, Nisar AD, Mudasir AB, Mudasir HB (2014) Prospects, Utilization and Challenges of Botanical Pesticides in Sustainable Agriculture. Inter J Mole Biol Biochem 1: 1-14.

- Devi KB, Pavankumar P, Bhadraiah B (2017) Antifungal Activity of Plant Extracts against Post-Harvest Fungal Pathogens. Inter J Cur Microbiol Appl Sci 6: 669-679.

- Dey KR, Choudhury P, Dutta BK (2015) Impact of Pesticide Use on the Health of Farmers: A study in Barak Valley, Assam (India). J Environ Chem Ecotoxic 10: 269-277.

- Dubey M, Thind TS, Dubey RK, Jindal SK (2016) Efficacy of Plant Extracts against Tomato Late Blight under Net House Conditions. Ind J Ecol 1: 375-377.

- Edema R (1995) Investigation into factors affecting diseases occurrence and farmer control strategies on cowpea in Uganda M Sc. Thesis Mackerel University Kampala.

- El-Wakeil NE (2013) Botanical Pesticides and their Mode of Action. Gesunde Pflanzen 65: 125-149.

- Elyousr KAA, Khan Z, Award EMM, Moneim MFA (2010) Evaluation of plant extracts and Pseudomonas spp for control of root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita on tomato. Nematropica 40: 289-299.

- Elzinga JA, Bier, A, Harvey JA (2002) The Rearing of the Gregarious Koinobiont Endoparasitoid Microplitis tristis (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) on Its Natural Host Hadena bicruris (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Proceedings Section Experimental and Applied Entomology of the Netherlands Entomological Society 13: 109-115.

- Esitken A, Yildiz HE, Ercisli S, Donmez MF, Turan M et al. (2009) Effects of Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria (PGPB) on Yield, Growth and Nutrient Contents of Organically Grown Strawberry. Scientia Horticulturae 124: 62-66.

- European Commission (2012) Amending Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 669/2009 Implementing Regulation (EC) No 882/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards the Increased Level of Official Controls on Imports of Certain Feed and Food of Non-Animal Origin. Official J Eur Uni L 350.

- Fawzi EM, Khali AA, Afif AF (2009) Antifungal effect of some plant extracts on Alternaria alternata and Fusarium oxysporum. Afr J Biotech 8(11): 2590–2597.

- Fernando LCP, Aratchige NS, Kumari SLML, Appuhamy PALD, Hapuarachchi DCL et al. (2006) Development of a Method for Mass Rearing of Neoseiulus baraka, a Mite Predatory on the Coconut Mite, Aceria guerreronis. J Coconut Res Inst Sri Lanka 16: 22-36.

- Fiedler Z (2012) Interaction Between Beneficial Organisms in Control of Spider Mite Tetranychus urticae (Koch.) J Pl Protect Res 2: 226-229.

- Flett BC, Bensch MJ, Smit E (1996) A field guide for identification of maize diseases in South African Agricultural Research Council potchefstoom 1996.

- Galko J, Nikolov C, Kunca A, Vakula J, Gubka A et al. (2016) Effectiveness of Pheromone Traps for the European Spruce Bark Beetle: A Comparative Study of Four Commercial Products and Two New Models. Lesnícky Casopis-Forestry J 62: 207-215.

- Gasic S, Tanovic B (2013) Biopesticide Formulations, Possibility of Application and Future Trends. J Pest Phytomed (Belgrade) 2: 97-102

- Gerson U (2014) Pest Control by Mites (acari): Present and Future. Acarologia 4: 371-394.

- Ghorab MA, Khalil MS (2015) Toxicological Effects of Organophosphates Pesticides. Inter J Environ Monito Anal 4: 218-220.

- Ghorbani R, Wilcockson S, Leifert C (2005) Alternative Treatments for Late Blight Control in Organic Potato: Antagonistic Micro-Organisms and Compost Extracts for Activity against Phytophthora infestans. Potato Res 48: 181-189.

- Gill RJ, Rodriguez, R, Raine NE (2012) Combined pesticide exposure severely affects individual and colony level traits in bees. Nat 491(7422): 105-8.

- Gnanamanickam SS (2002) Biological control of crop diseases. Marcel Dekker Inc.

- Goufo P, Mofor TC, Fontem DA, Ngnokam D (2008) High Efficacy of Extracts of Cameroon Plants against Tomato Late Blight Disease. Agron Sust Dev 4: 567-573.

- Grenier S (2009) In Vitro Rearing of Entomophagous Insects - Past and Future Trends: A Mini review Bulletin Insectology. 1: 1-6.

- Grenier S (2012) Artificial Rearing of Entomophagous Insects, with Emphasis on Nutrition and Parasitoids-General Outlines from Personal Experience. Karaelmas Sci Eng J 2: 1-12.

- Gupta S, Dikshit AK (2010) Biopesticides: An Ecofriendly Approach for Pest Control. J Biopesticides 1: 186-188.

- Halimatunsadiah AB, Norida M, Omar D, Kamarulzaman NH (2016) Application of Pesticide in Pest Management: The Case of Lowland Vegetable Growers. Inter Food Res J 1: 85-94.

- Harada T, Takeda M, Kojima S, Tomiyama N (2016) Toxicity and Carcinogenicity of Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). Toxicol Res 32(1):21-33.

- Hassanein MN, Abou ZMA, Youssef AK, Mahmoud AD (2010) Control of Tomato Early Blight and Wilt using Aqueous Extract of Neem Leaves. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 49: 143-151.

- Hossain MA ALsabari KM, Weli AM (2013) Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis and Total Phenolic Contents of Various Crude Extracts from the Fruits of Datura metel L. J Taibah Uni Sci 7: 209-215.

- Hussain F, Abid M, Shauka, S, Farzana S, Akbar M (2015) Anti-Fungal Activity of Some Medicinal Plants on Different Pathogenic Fungi. Pakis J Bot 5: 2009-2013.

- Iberê FS, Oliveira RG, Soares IM, Alvim TC, Ascêncio SD et al. (2014) Evaluation of Acute Toxicity, Antibacterial Activity and Mode of Action of the Hydro Ethanolic Extract of Piper umbellatum L. J Ethnopharma 151(1):137-43.

- Islam MR, Jeong YT, Lee YS, Song CH (2012) Isolation and Identification of Antifungal Compounds from Bacillus subtilis C9 Inhibiting the Growth of Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Mycobiology 40(1):59-66.

- Islam MR, Mondal C, Hossain I, Meah BM (2013) Organic Management: An Alternative to Control Late Blight of Potato and Tomato Caused by Phytophthora infestans. Inter J Theor Appl Sci 2: 32-42.

- Islam MR, Monda C, Hossain I, Meah BM (2014) Compost Tea as Soil Drench: An Alternative Approach to Control Bacterial Wilt in Brinjal. Archiv. Phytopath Pl Protect 12: 1475-1488.

- Jahangiriana H, Haron MDJ, Mohd HSIA, Roshanak R, Leili ADYAE (2013) Well Diffusion Method for Valuation of Antibacterial Activity of Copper Phenyl Fatty Hydroxamate Synthesized from Canola and Palm Kernel Oils Digest J Nanomater. Biostruct 3: 1263-1270.

- Jalili-Marandi R, Hassani A, Ghosta Y, Abdollahi A, Pirzad A et al. (2010) Thymus kotschyanus and Carumcopticum essential oils as botanical preservatives for table grape. J Med Pl Res 4(22): 2424-2430.

- Jantasorn A, Moungsrimuangdee B, Dethoup T (2016) In Vitro Antifungal Activity Evaluation of Five Plant Extracts against Five Plant Pathogenic Fungi Causing Rice and Economic Crop Diseases. J Biopest 1: 1-7.

- Javaid A, Rehman AH (2011) Antifungal Activity of Leaf Extracts of Some Medicinal Trees against Macrophomina phaseolina. J Med Pl Res 13: 2858-2872.

- Javaid MK, Ashiq M, Tahir M (2016) Potential of Biological Agents in Decontamination of Agricultural Soil.

- Kachhawa D (2017) Microorganisms as a Biopesticides. J Entom Zoo Stud 3: 468-473.

- Karimi K, Amini J, Harighi B, Bahramnejad B (2012) Evaluation of Biocontrol Potential of Pseudomonas and Bacillus spp against Fusarium Wilt of Chickpea. Aust J Crop Sci 6: 695-703.

- Kawalekar JS (2013) Role of Biofertilizers and Biopesticides for Sustainable Agriculture. J Bio Innov 2: 73-78.

- Kekuda PTR, Akarsh S, Nawaz SAN, Ranjitha MC, Darshini SM et al. (2016) In Vitro Antifungal Activity of Some Plants against Bipolaris sarokiniana (Sacc.) Shoem. Inter J Cur Microbiol Appl Sci 6: 331-337.

- Kenis M, Hurley BP, Hajek AE, Cock MJW (2017) Classical Biological Control of Insect Pests of Trees: Facts and Figures. Biological Invasions,19: 3401-3417.

- Khan AI, Hussain S, Akbar R, Saeed M, Farid A et al. (2015) Efficacy of a Biopesticide and Synthetic Pesticides against Tobacco Aphid, Myzus persicae Sulz. (Homoptera, Aphididae), on Tobacco in Peshawar. J Entomol Zoo Stud 4: 371-373.

- Khanamani M, Fathipour BY, Talebi AA, Mehrabadi M (2017) Evaluation of Different Artificial Diets for Rearing the Predatory Mite Neoseiulus californicus (Acari: Phytoseiidae): Diet Dependent Life Table Studies. Acarologia 2: 407-419.

- Khater HF (2012) Prospects of Botanical Biopesticides in Insect Pest Management. Pharmacologia 12: 641-656.

- Knutson A, Ruberson J (2015) Field Guide to Predators, Parasites and Pathogens Attacking Insect and Mite Pests of Cotton. In: Smith EM, Ed, Texas Cooperative Extension, TX Publication Pp136.

- Kokalis-Burelle N (2015) Pasteuria penetrans for Control of Meloidogyne incognita on Tomato and Cucumber, and M. arenaria on Snap Dragon. J Nematol 3: 207-213.

- Koul O (2011) Microbial Biopesticides: Opportunities and Challenges. CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources, 6: 056.

- Kumar S, Singh A (2015) Biopesticides: Present Status and the Future Prospects. J Fert Pest 2: 1-2.

- Kumari A, Kumar KNR, Rao CHN (2014) Adverse Effects of Chemical Fertilizers and Pesticides on Human Health and Environment. Proceedings National Seminar on the Impact of Toxic Metals, Minerals and Solvents leading to Environmental Pollution. J Chem Pharma Sci 3: 150-151.

- Lanzoni A, Martelli R, Pezzi F (2017) Mechanical Release of Phytoseiulus persimilis and Amblyseius swirskii on Protected Crops. Bull Insectol 2: 245-250.

- Lee W, Ho C, Lo K (1990) Mass Production of Phytoseiids: Evaluation of Eight Host Plants for the Mass-Rearing of Tetranychus urticae and T. kanzawai Kishda (Acarina: Tetranychidae). Agric Sci China 2: 121-132.

- Leng P, Zhang Z, Pan G, Zhao M (2011) Applications and Development Trends in Biopesticides. Afr J Biotech 86: 19864-19873.

- Mahlo SM, Chauk HR, McGaw LJ, Eloff JN (2013) Antioxidant and Antifungal Activity of Selected Plant Species Used in Traditional Medicine. J Med Pl Res 33: 2444-2450.

- Maksymiv I (2015) Pesticides: Benefits and Hazards. J Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian Nat Uni1: 70-76.

- Mendoza JLH, Pérez MIS, Prieto JMG, Velásquez JDQ, Olivares JGG et al. (2015) Antibiosis of Trichoderma spp Strains Native to Northeastern Mexico against the Pathogenic Fungus Macrophomina phaseolina. Brazil J Microbiol 4: 1093-1101.

- Minz, S., Samuel, C.O., Tripathi, C.S. (2012) The Effect of Plant Extracts on the Growth of Wilt Causing Fungi Fusarium oxysporum. J Pharm Biol Sci 1: 13-16.

- Mizubuti GSE, Junior VL, Forbes GA (2007) Management of Late Blight with Alternative Products. Pest Tech 2: 106-116.

- Morales-Ramos JA, Rojas MGA (2014) Modular Cage System Design for Continuous Medium to Large Scale in Vivo Rearing of Predatory Mites (Acari: Phytoseiidae).

- Moreira MD, Picanco MC, Barbosa LCA, Guedes RNC, Campos MR et al. (2007) Plant Compounds Insecticide Activity against Coleoptera Pests of Stored Products. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira 7: 909-915.

- Morrissey WA (2006) Methyl Bromide and Stratospheric Ozone Depletion. CRS Report for Congress 1-6.

- Muthomi JW, Lengai GMW, Wagacha JM, Narla RD (2017) In Vitro Activity of Plant Extracts against Some Important Plant Pathogenic Fungi of Tomato. Aust J Crop Sci 6: 683-689.

- Muzemu S, Mvumi BM, Nyirenda SPM, Sileshi GW, Sola P et al. (2011) Pesticidal Effects of Indigenous Plant Extracts against Rape Aphids and Tomato Red Spider Mites. African Crop Science Conference Proceedings 10: 171-173.

- Naing WK, Anees M, Nyugen HX, Lee SY, Jeon WS et al. (2013) Biocontrol of Late Blight Diseases (Phytophthora Capsici) of Pepper and the Plant Growth Promotion by Paenibacillus chimensis KWNJ8. J Phytopath 2: 164-165.

- Nashwa SMA, Abo-Elyousr AMK (2012) Evaluation of Various Plant Extracts against the Early Blight Disease of Tomato Plants under Green House and Field Conditions. Pl Prot Sci 2: 74-79.

- Nawaz M, Mabubu JI, Hua H (2016) Current Status and Advancement of Biopesticides: Microbial and Botanical Pesticides. J Entomol Zoo Stud, 2: 241-246.

- Ndakidemi B, Mtei K, Ndakidemi PA (2016) Impacts of Synthetic and Botanical Pesticides on Beneficial Insects Agric Sci 7: 364-372.

- Nefzi A, Abdallah BAR, Jabnoun-Khiareddine H, Saidiana-Medimagh S, Haouala Ret al. (2016) Antifungal Activity of Aqueous and Organic Extracts from Withania somnifera L. against Fusarium oxysporum fsp radicislycopersici. J Microbial Biochem Techn 8: 144-150.

- Ngegba PM, Kanneh SM, Bayon MS, Ndoko EJ, Musa PD et al. (2018a) Fungicidal Effect of Three Plants Extracts in Control of Four Phytopathogenic Fungi of Tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum L.) Fruit Rot. Inter J Environ Agric Biotechn 1: 112-117.

- Nia B, Frah N, Azoui I (2015) Insecticidal Activity of Three Plants Extracts against Myzuspersicae (Sulzer, 1776) and Their Phytochemical Screening. Acta Agric Slovenica 2: 261-267.

- Nweke IA (2018b) In support of a well-planned intercropping systems in southeastern soils of Nigeria: A review. Afr J Agric Res 13(26): 1320-1330.

- Nweke IA (2018c) Residual effect of organic waste amendment on soil productivity and crop yield-A review. Greener J Agric Sci 8(9): 209-218.

- Nweke IA (2020a) Soil testing a panacea to crop yield and agricultural sustainability – a case for farmers of southeastern, Nigeria. J Agric Sci 2(2): 7-14.

- Nweke IA (2020b) Potentials of intercropping systems to soil - water - plant- atmosphere. J Agric Sci 2(1): 31-38.

- Nweke IA (2020c) Alley cropping for soil and agricultural sustainability in southeastern soils of Nigeria. Sumerianz J Agric Veter 3(1): 1-6.

- Nweke IA, Chukwuma TR (2023) Effect of castor capsules (Ricinus communis) and neem leaves (Azadiracta indica) on soil properties and fungi infection on tomato (Lycopesicum esculentum) Global Scientific Journals (GSL) 11(2): 1999-2010.

- Odhiambo AJ, Siboe GM, Lukhoba CW, Dossaji FS (2009) Antifungal Activity of Crude Extracts of Selected Medicinal Plants Used in Combination in Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya. Pl Prod Res J 13: 35-43.

- Okunlola AI, Akinrinnola O (2014) Effectiveness of Botanical Formulations in Vegetable Production and Bio-Diversity Preservation in Ondo State, Nigeria. J Hortic For 1: 6-13.

- Oyedokun AV, Anikwe JC, Okelana FA, Mokwunye IU, Azeez OM et al. (2011) Pesticidal Efficacy of Three Tropical Herbal Plants’ Leaf Extracts against Macrotermes bellicosus, an Emerging Pest of Cocoa, Theobroma cacao L. J Biopest 2: 131-137.

- Pal KK, McSpadde, GB (2006) Biological Control of Plant Pathogens. The Pl. Health Instr 10: 1-25.

- Pandey S, Gill RS, Mandal K (2016) Persistence and Efficacy of Spinosad, Indoxacarb and Deltamethrin against Major Insect Pests of Stored Wheat. Pest Res J 28: 178-184.

- Pane C, Palese AM, Celano G, Zaccardelli M (2014) Effects of Compost Tea Treatments on Productivity of Lettuce and Kohlrabi Systems under Organic Cropping Management. Italian J Agron 3: 1-4.

- Park JP, Gyung JC, Kyoung SJ, He KL, Heung TK et al. (2005) Antifungal Activity against Plant Pathogenic Fungi of Chaetoviridins Isolated from Chaetomium globosum. FEMS Microbiol Letters 252(2):309-13.

- Parliman DJ (2001) Soil Analyses for 1, 3-Dichloropropene (1, 3-DCP), Sodium N Methyldithiocarbamate (Metam-Sodium), and Their Degradation Products near Fort Hall, Idaho, September 1999 through March 2000. Water-Resources Investigations Report 01: 4052.

- Parte SG, Kharat AS, Mohekar AD, Chavan JA, Jagtap AA et al. (2015) Efficacy of Plant Extracts for Management of Cimex lectularius (Bed Bug). Inter J Pure Appl Biosci 3: 506-508.

- Pascual JA, Hernandez T, Garcia C, Lerma S, Lynch JM et al. (2002) Effectiveness of municipal waste compost and its humic fraction in suppressing pythiumultimum. Microbial Ecol 44: 59-68.

- Patrice AK, Séka K, Francis YK, Théophile AS, Fatoumata F et al. (2017) Effects of Three Aqueous Plant Extracts in the Control of Fungi Associated with Post-harvest of Yam (Dioscorea alata). Inter J Agron Agric Res 3: 77-87.

- Pendse MA, Karwander PP, Limaye MN (2013) Past, present and future of nematopathogenic fungi as bioagent to control plant parasitic nematodes. J Pl Protect Sci 5(1): 1-9.

- Powell W, Pickett JA (2003) Manipulation of Parasitoids for Aphid Pest Management: Progress and Prospects. Pest Manag Sci 59(2):149-55.

- Prasad A, Syed N (2010) Evaluating Prospects of Fungal Biopesticide Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) against Helicoverpa armigera (Hubner): An Eco-Safe Strategy for Pesticidal Pollution. Asian J Experi Biol Sci 3: 596-601.

- Radhakrishnan B (2010) Indigenous botanicals preparations for pest and disease control in tea. Bul. UPASI Tea Res Found 55: 31-39.

- Randhawa N, Sakhuja PK, Singh I (2001) Management of root- knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita in tomato with organic amendments. Pl Dis Res 16: 274–276.

- Rao KS, Vishnupriya R, Ramaraju K (2017) Efficacy and Safety Studies on Predatory Mite, Neoseiulus longispinosus (Evans) against Two-Spotted Spider Mite, Tetranychusurticae Koch under Laboratory and Greenhouse Conditions. J Entom Zoo Stud 4: 835-839.

- Refki E, Sadok BM, Ali BB, Faouzi A, Jean VF et al. (2016) Effectiveness of Pheromone Traps against Tuta absoluta. J Entom Zoo Stud 6: 841-844.

- Rodino S, Butu A, Butu M, Cornea CP (2012) In Vitro Efficacy of some Plant Extracts against Damping off Disease of Tomatoes. Journal of International Scientific Publications: Agric Food 2: 240-244.

- Romanazzi G, Lichter A, Gabler FM, Smilanick JL (2012) Recent advances on the use of natural and safe alternatives to conventional methods to control postharvest grey mold of table grapes. Postharvest Bio Techn 63: 141-147.

- Sahu DK, Khare CP, Patel R (2014) Eco-Friendly Management of Early Blight of Tomato Using Botanical Plant Extracts. J Ind Poll Cont 2: 215-218.

- Sales MDC, Costa HB, Fernandez PMB, Ventura JA, Meira DD et al. (2016) Antifungal Activity of Plant Extracts with Potential to Control Plant Pathogens in Pineapple. Asian Pacific J Trop Biomed 1: 26-31.

- Salim HA, Salman IS, Ishtar IM, Hatam HH (2016) Evaluation of Some Plant Extracts for their Nematicidal Properties against Root-Knot Nematode (Meloidogyne sp). J Gen Environ Res Conserv 3: 241-244.

- Sarles L, Verhaeghe A, Francis F, Verheggen FJ (2015) Semiochemicals of Rhagoletis Fruit Flies: Potential for Integrated Pest Management. Crop Protect 78: 114-118.

- Selim HMM, Gomaa NM, Essa AMM (2016) Antagonistic Effect of Endophytic Bacteria against Some Phytopathogens. Egyptian Bot 1: 74-81.

- Semeniuc CA, Pop CR, Rotar AM (2017) Antibacterial Activity and Interactions of Plant Essential Oil Combinations gainst Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. J Food Anal 25: 403-408.

- Sesan TE, Enache E, Iacomi M, Oprea M, Oancea F et al. (2015) Antifungal Activity of some Plant Extract against Botrytis cinerea Pers. in the Blackcurrant Crop (Ribes nigrum L). Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Technologia Alimentaria 1: 29-43.

- Shah JA, Inayatullah M, Sohail K, Shah SF, Shah S et al. (2013) Efficacy of Botanical Extracts and a Chemical Pesticide against Tomato Fruit Worm (Helicoverpa armigera). Sarhad J Agric, 1: 93-96.

- Shiberu T, Getu E (2016) Assessment of Selected Botanical Extracts against Liriomyza Species (Diptera: Agromyzidae) on Tomato under Glasshouse Condition. Inter J Fauna Bio Stud 1: 87-90.

- Sidhu SH, Kumar V, Madhu MR (2017) Eco-Friendly Management of Root-Knot Nematode, Meloidogyne javanica in Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) Crop. Inter J Pure Appl Biosci 1: 569-574.

- Sikora RA (2005) Fernandez E Nematode parasites of vegetables, p. 319–392. In: “Plant- Parasitic Nematodes in Sub- tropical and Tropical Agriculture” (M Luck, RA Sikora J eds).

- Silva FR, Moraes GJ, Gondim MGC, Knapp M, Rouam Sl et al. (2010) Efficiency of Phytoseiulus longipes Evans as a Control Agent of Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard (Acari: Phytoseiidae: Tetranychidae) on Screen House Tomatoes. Neotropical Entomology, 39(6):991-5.

- Singh HB (2014) Management of Plant Pathogens with Microorganisms. Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy 2: 443-454.

- Song CH, Islam RMD, Jeong YT, Lee YS (2012) Isolation and Identification of Antifungal Compounds from Bacillus subtilis C9 Inhibiting the Growth of Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Mycobiology 40(1):59-66.

- Souza R, Ambrosini A, Passaglia LMP (2015) Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria as Inoculants in Agricultural Soils. Gen Mol Bio 38(4):401-19.

- Srijita D (2015) Biopesticides: An Eco-friendly Approach for Pest Control. World J Phar Pharmaceut Sci 6: 250-265.

- Steinberg S (2013) Novel Technologies in Mass Rearing of Beneficial Arthropods. Proceedings of the Annual Biocontrol Industry Meeting Bael 1-28.

- Stoneman B (2010) Challenges to Commercialization of Biopesticides, Proceedings Microbial Biocontrol of Arthropods, Weeds and Plant Pathogens: Risks, Benefits and Challenges. National Conservation Training Center Shepherdstown WV.

- Sumitra A, Kanojia AK, Kumar A, Mogha N, Sahu V et al. (2014) Biopesticide Formulation to Control Tomato Lepidopteran Pest Menace. Cur Sci 7: 1051-1057.

- Sunder J, Singh DR, Jeyakumar S, Kundu A, Kumar A et al. (2011) Antibacterial Activity in Solvent Extract of Different Parts of Morinda citrifolia plant. J Pharmaceut Sci Res 8: 1404-1407.

- Suprapta DN (2012) Potential of Microbial Antagonists as Biocontrol Agents against Plant Fungal Pathogens. Inter Soc Southeast Asian Agric Sci J 2: 1-8.

- Taye W, Sakhuja PK, Tefera T (2012) Evaluation of plant extracts on infestation of root-knot nematodes on tomato (Lycopersicon esculemtum Mill). J Agric Res Develop 2(3): 86-91.

- Vidyasagar GM, Tabassum N (2013) Antifungal Investigations on Plant Essential Oils: A Review. Inter J Phar Pharmaceut Sci 2: 19-28.

- Vinale F, Krishnapillai S, Ghisalbertic LE, Marraa R, Wooa LS et al. (2008) Trichoderma-Plant-Pathogen Interactions. Soil Bio. Biochem 40: 1-10.

- Wetungu MW, Matasyoh JC, Kinyanjui T (2014) Antimicrobial Activity of Solvent Extracts from the Leaves of Tarchonanthus camphoratus (Asteraceae). J Pharmacog Phytochem 1: 123-127.

- Wu K, Lin K, Miao J, Zhang Y (2005) Field Abundances of Insect Predators and Insect Pests on δ-Endotoxin-Producing Transgenic Cotton in Northern China. Second International Symposium on Biological Control of Arthropods, Davos 362-368.

- Xavier G, Chandran M, Naseema BS, Mathew TB, George T et al. (2016) Persistence of Fenpyroximate in Chilli Pepper (Capsicum annum L.) and Soil and Effect of Processing on Reduction of Residues. Pest Res J 2: 145-151.

- Xiao Y, Wei X, Ebright R, Wall D (2011) Antibiotic Production by Myxobacteria Plays a Role in Predation. Journal of Bacteriology 193(18):4626-33.

- Xu X, Enkegaard A (2010) Prey Preference of the Predatory Mite, Amblyseius swirskii between First Instar Western Flower Thrips Frankliniella occidentalis and Nymphs of the Two-Spotted Spider Mite Tetranychus urticae. J Insect Sci 149: 1-11.

- Zarubova L, Lenka K, Pavel N, Miloslav Z, Ondrej D et al. (2014) Botanical Pesticides and Their Human Health Safety on the Example of Citrus sinensis Essential Oil and Oulema melanopus under Laboratory Conditions. Mendel Net pp. 330-336.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.