Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Comparison of Attenuation Tissue Imaging with UDFF of Intervendor Platforms for Liver Fat Estimation

*Corresponding author: Atul Kapoor, Departments of Radiology, Advanced Diagnostics and Institute of Imaging. Amritsar, India.

Received: March 11, 2025; Published: March 19, 2025

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2025.26.003428

Abstract

Background: This prospective cross-sectional study compared the performance of Attenuation Imaging (ATI) and Ultrasound-Derived Fat Fraction (UDFF) in quantifying and grading liver fat content in 88 patients with an increased risk of Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) and suspected chronic liver disease. Methods: The study included 88 patients (63 males, 25 females) with a mean age of 52 years and a mean BMI of 29.5 kg/m2 who had high risk of MAFLD and underwent Ultrasound based liver fat quantification on Canoni800 attenuation-based method and Siemens Sequioa based UDFF method. All discordant cases were confirmed using the MR-PDFF method. Results: The Canon Aplio and Siemens Sequoia systems successfully classified all cases into S0-S3 grades of fatty liver, with a moderate positive correlation (0.590) and 91% agreement within one grade difference. However, the Aplio system tended to grade slightly lower than Sequoia, with a mean difference of -0.29 grade. Subcutaneous fat thickness (SCD) emerged as a major confounding factor, accounting for 25-30% of the discordance, with the highest discrepancy rate (66.7%) observed in patients with SCD > 2.6cm. BMI, inflammation, and fibrosis did not significantly affect the grading discrepancies. Outlier cases with the largest absolute differences were primarily patients with the highest BMIs (>32) and SCD (>3.2). This study highlights high liver iron as another potential variable leading to measurement differences and suggests further evaluation for such patients. Conclusion: ATI and UDFF showed good agreement in grading liver fat content, with most differences within a single grade. SCD was a single univariate confounding factor and patients with high SCD and BMI had an odds ratio of 1.9 for grading discrepancies with 76% sensitivity. The study also highlights high liver iron as another potential variable leading to measurements, and suggests further evaluation for such patients.

Keywords: Elastography, Ultrasound derived fat fraction, Attenuation imaging, MASLD, Liver fibrosis

Introduction

Evaluation of liver fat content has become important because of the worldwide increase in the prevalence of Metabolic Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD), with a prevalence rate of 30% [1,2]. Ultrasound (US) is the basic modality used to diagnose fatty liver based on the increased echotexture of the liver [3]. However, the sensitivity for the detection of steatosis is less than 60% [4]. Routine ultrasonography cannot quantify steatosis, which is important for treatment planning and follow-up. US also lacks repeatability and has high subjectivity in classifying fatty liver; therefore, the MR-based Proton Density Fat Fraction (PDFF) protocol was established as the gold standard for the diagnosis of MAFLD [5]. The use of MR also has limitations in terms of cost, cumbersome nature, and lack of easy availability. Therefore, newer ultrasound-based methods have been developed to analyse sound waves emitted from transducers and quantify fat in the liver parenchyma. Four US-based methods are used: a) Attenuation-based imaging (AC), b) Backscatter Coefficient Estimation (BSC), c) Speed of sound analysis, and d) Combination of AC and BSC-ultrasound-derived fat fraction (UDFF), [6-9]. AC has been used by Canon in Aplio systems to determine the attenuation coefficient in the assessment of MAFLD [10-11] similarly the novel technique of UDFF has been used by Siemens in the Sequioa system [12]. Likewise, there have been other algorithms using same principles by different vendors with acronyms like CAP (Controlled Attenuation Parameter), USAT (Ultrasound Attenuation Analysis) and UGAP (Ultrasound Guided Attenuation Parameter) and they all primarily focus on the diagnostic performance of their individual techniques and there is a gap in research regarding direct comparisons between different vendors algorithms that needs to be addressed.

This study was designed to compare the results of both systems for quantification and grading of liver fat content in patients with an increased risk of MAFLD and in patients with coexisting advanced chronic liver disease to determine their concordance in results and to determine if any confounding factors of variance are present.

Material and Methods

Study Population

Approval for the study was obtained from the local ethics review board (Aerb030624) and all participants provided informed consent. Power analysis was performed to obtain a power factor of 0.9 with a p-value of 0.05, for which a minimum of 87 patients were needed to complete the study. A total of 88 patients were enrolled in a single-center cross-sectional prospective study from July to November. The inclusion criteria were undiagnosed adults aged >25 years with an increased risk of fatty liver disease, such as diabetes, abnormal liver enzymes, overweight and obesity, or a history of treated hepatitis with adequate breath-holding. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, malignancy, chronic alcoholism with daily intake of more than 200ml/day or severe comorbidities with inadequate breath holding. Height, weight, and clinical data were recorded, and BMI was calculated to correlate the demographic data. The patients ranged in age from 25 to 80 years and presented with clinical presentations of MAFLD, NASH, Advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD), and isolated increased liver transaminases. All patients fasted for at least 4h and informed consent was obtained. Patients were made to lie supine on the examination bed, and routine gray-scale ultrasound of the liver was performed by an experienced sonologist with 30 years of experience in sonography and 15 years of experience in elastography. This was followed by a fat quantification protocol on two machines, Canon Aplio i800, using the ATI technique based on attenuation, and Siemens Sequioa version 2.0, using the hybrid imaging technique, UDFF.

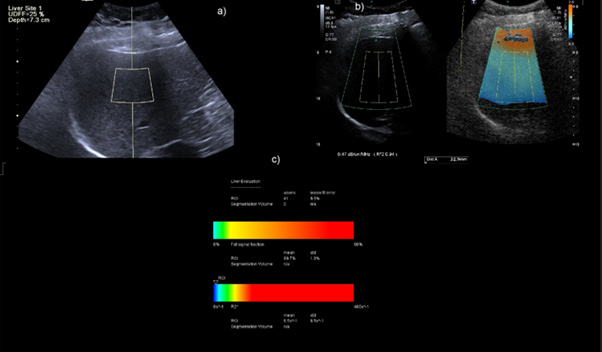

The patient abducted the right arm to its maximum extent during the measurements to fully expose the intercostal space. Liver morphology was first assessed using grayscale ultrasonography with a curvilinear probe (5C1, 1.0-5.7 MHz). Subsequently, the UDFF and pSWE measurements were conducted separately using a deep abdominal transducer (DAX, 1.0-3.5 MHz). The manufacturer predefined the fixed and unchangeable ROI depth and size (1.5cm from the liver capsule; 3cm × 4cm). The horizontal positioning line was aligned with the liver capsule to ensure accurate measurement depth and data collected in the breath-hold position. Five measurements were taken and the median was taken as the final percentage of fat. Finally, the skin-to-liver capsule distance (SCD) was estimated for all patients.

A similar positioning technique was used for Canon Aplio i800 measurements. A convex 5C (1-6.2 MHz) was used in this study. After the gray scale, the ATI mode was selected and a color-coded box appeared, which showed a large area of interest for attenuation in real time. All the vessels and artifacts were filtered out. Reverberation artifacts are also separately labelled in orange and excluded. The measurement area consisted of another ROI of 5 × 3cm in the center, with the patient holding their breath. Five measurements were recorded with R2 >0.90 and the median value was obtained in dB/cm/MHz. This was followed by elastography measurements at the same position for the estimation of liver stiffness in kilopascals and shear wave dispersion in m/s(kHz).

Data Analysis

All collected data were sorted into an Excel spreadsheet and graded before analysis. The Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated for all patients. Liver fat content was graded from S0-S3 grades based on vendor guidelines. For the Canon i800 (ATI) S0: <0.63bB/ cm/MHz S1: 0.63-0.72; S2 0.72-0.82 and S3 >0.82 dB/cm/MHz For Siemens Sequoia UDFF; S0>5%, S1: 5%-15% S2: 16%-25% and S3: >25%.

In cases of discordance, MRI-PDFF was performed on a Siemens 1.5Tesla Amira system on the same day with automated Liver Lab software, and the percentage of liver fat along with liver iron content was estimated.

Statistical Analysis

All demographic data were analyzed using STATX and Analyze- IT software to normalize the distribution before choosing the tests. Mean values and confidence intervals were also calculated for demographic data and for the categories of fatty grades estimated for both systems. The Bland-Altman test was used to determine the differences in the mean. Spearman’s correlation was performed to determine variable correlation along with the ANOVA test to determine the statistical significance. The mean difference test was estimated in cases of discordance, and further tests with diagnostic analysis were performed using the Mann-Whitney test for the cause of discrepancy. The chi-square test was performed for categorical variables to test statistical significance. Both univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed to detect the importance of the variables.

Results

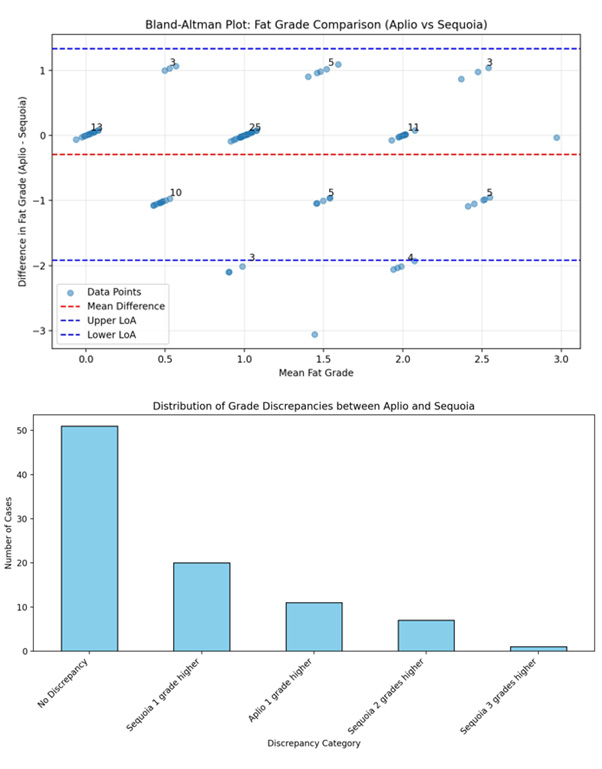

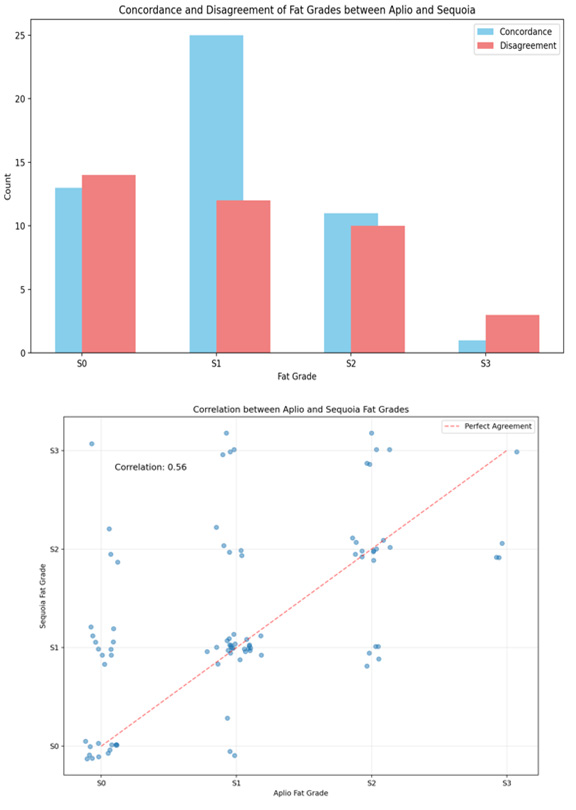

The study included 88 patients, of whom 63 were male and 25 were female and showed a clear male predominance in the study population. The mean age of the patients was 52 years (range: 22- 80 years). The mean BMI was 29.5 kg/m2 (range 27.3-32.9 Kg/m2) with a slight right-sided skew. Most patients were in the overweight category (53), followed by the obese category (32), while only (4) patients had a normal BMI, and there were no patients in the underweight category. SCD showed a relatively normal distribution, with a median of 2.19 cm (range, 1.78-3.7cm) (Figure 1). The most common clinical diagnoses in this cohort were MASLD (31) and advanced chronic liver disease ACLD (29). Both Aplio and Sequoia successfully classified all cases into S0-S3 grades of fatty liver, and the distribution is shown in a bar chart and scatter plot (Figure 2a, b) with a positive moderate correlation (0.59 to classify grades of steatosis and with an absolute concordance of 56% (Figure 3). On average, Aplio tended to grade slightly lower than Sequoia, with a mean difference of -0.29 grade which was small, with maximum differences seen in the S3 grade. The Bland-Altman test of comparison between the two systems showed 91% agreement with no or one grade difference, of which 56.2% was in absolute agreement, 34.8% was a one-grade difference, and 9% patients had a two-grade difference (Figure 4a, b). The Spearman correlation test for significance between all variables revealed a strong moderate positive correlation between the Aplio and Sequoia Fat Grades (0.586, p < 0.001), weighted Kappa of 0.52 with Chi square test showing p=0.0001. An absolute mean difference of 0.53 was seen between the two systems (Figure 4).

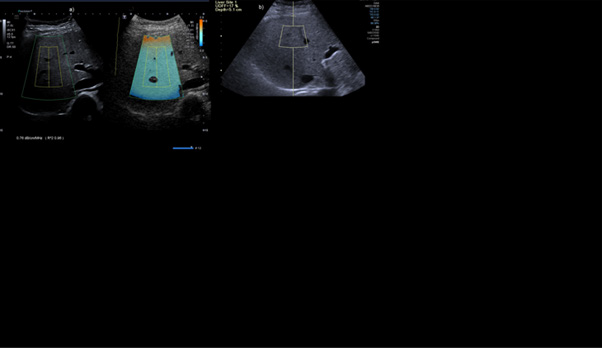

Figure 3: Concordant case of Category S2 grade patient on Aplio showing ATI of 0.76db/cm/MHz b) UDFF of 17% in the same patient.

Figure 4: a) Bland Altman test of difference of means between Aplio and Sequioa grades b) Bar chart showing distribution of concordance and discordance in grades of fatty liver.

Grade-Specific Patterns

A. S0 (Aplio): Shows 51.9% disagreement rate

i. Most common disagreement: 10 cases where Aplio labelled grade S0 but with Sequoia it was S1

ii. More severe disagreements: 3 cases of S2 and 1 case of S3 by Sequoia

B. S1 (Aplio): Shows 32.4% disagreement rate

i. Balanced disagreement: Both upgrades and downgrades

ii. 3 cases downgraded to S0

iii. 9 cases upgraded to S2/S3

C. S2 (Aplio): Shows 50% disagreement rate

i. Mixed pattern: 5 cases each of S1 and S3 by Sequoia

ii. Shows both upgrade and downgrade patterns

D. S3 (Aplio): Shows 75% disagreement rate

i. Only 3 cases of disagreement, all downgraded to S2 by Sequoia

ii. Small sample size (only 4 total S3 cases)

Most disagreements (35.2%) were one-grade differences, which may be clinically acceptable.

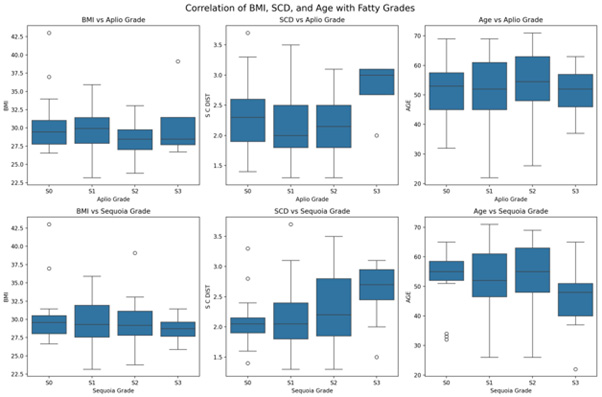

Further analysis showed that obese patients had the largest grade difference of 0.344, overweight patients showed a 0.283 grade measurement difference, and patients with a normal BMI had no average difference between the measurements. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test ranked these differences as statistically significant (p=0.0318) and (p=0.0157) for the obese and overweight categories, respectively, whereas p=1.0000 was observed for the normal BMI category (p=1.0000) (Figure 5).

Correlation analysis of age, sex, BMI, and SCD showed a positive association between BMI and SCD and the fatty grades of both Aplio and Sequioa. ANOVA revealed that the BMI association was statistically insignificant (p=1.0000). An analysis of discrepant cases between the two systems of fatty liver grading systems was performed for confounding variables.

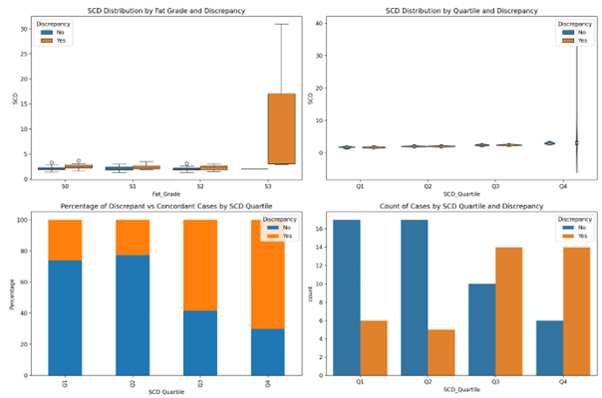

We analysed the effect on two variables SCD and BMI in discrepant cases and is shown in box plots.

The effect of SCD: SCD ratio showed a statistically significant difference in the ANOVA test between the three groups (p=0.001). The median SCD value for S3 cases (3.0) was higher than that for non-S3 cases (2.1), suggesting that S3 cases tended to have higher SCD values. (p=0.039), while S2 discrepant cases showed (2.31 vs 2.0; p=0.045). The Kruskal-Wallis test showed a statistically significant difference of 0.055, with a Progressive Pattern across S0-S2 discrepant cases (Figure 6).

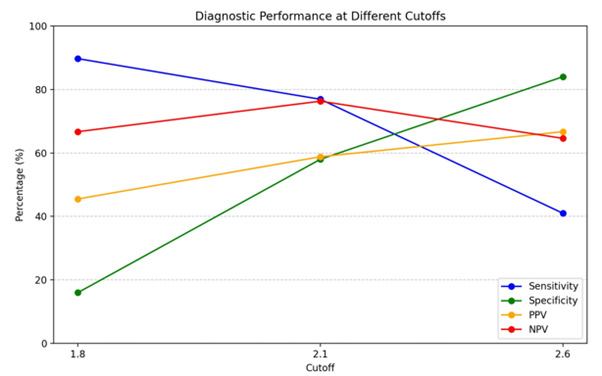

Quartile analysis was also performed, and SCD was classified into four quartiles. Q1 (First Quartile): ≤ 1.8

Q2 (Second Quartile): 1.8 -2.1, Q3 (Third Quartile): 2.1 -2.6, Q4 (Fourth Quartile): ≥ 2.6

The results showed that the highest discrepancy rate was 66.7% in patients with cut-off SCD>2.6. A cut of 2.1 provides a good balance of sensitivity 76.9% and specificity (58.0%), and as the cutoff increases, sensitivity falls. PPV increased with a higher SCD cutoff but was associated with higher discrepancies (Figures 6,7).

Effect of BMI on discrepant cases: ANOVA indicated no statistically significant difference in BMI across the discrepancy groups (p=0.946), suggesting that BMI does not have a strong effect on grading discrepancies.

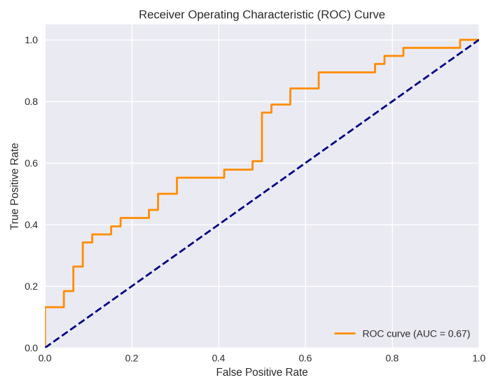

Multivariate logistic regression analysis model showed when BMI was combined with SCD they had the largest statistical significant impact on grade discordances (p value 0.037) with an odds ratio of 1.95, (CI 1.04-3.6) indicating a strong interaction effect with AUC of 67% (Figure 8).

Analysis of Outliers

The outliers with the largest absolute differences (two or more grades) were primarily patients with the highest BMIs (>32), highest SCD (>3.2), or both, with S3 graded as S1 by Aplio (Figures 9,10). There were two outlier cases with SCD >2.5 and BMI <30, where fat grades S2,3 on sequoia were graded as S0 and S1 by Aplio (Figure 9). The latter cases indicate measurement inconsistencies owing to high SCD patient characteristics that affect agreement. The correlation MRI of the other outlier patients revealed high liver ferritin levels, which was a confounding factor leading to a systematic bias (Figure 10). We also analyzed 38 cases with discrepant grades of inflammation and fibrosis as confounding factors for discrepancies in steatosis grades. The mean SWD in cases without grade discrepancy were 15.07 while SWD grade discrepancy and 13.81%, respectively. The t-test p-value (0.233) indicates no statistically significant difference in SWD between discrepancy and non-discrepancy groups (Figure 11).

Discussion

MR-PDFF is considered the gold standard for liver fat quantification, but it is both expensive and inexpensive. ATI and UDFF are techniques comparable to MR-PDFF for the same purpose [7]. Aplio used ATI measuring the energy loss of the sound waves while UDFF also takes into account the BSC which changes with the microstructure of tissue and theoretically is more sensitive and gives a numerical figure in percentages which appears more acceptable. Our study is unique because it conducts a prospective evaluation of the predominant population of overweight and obese patients with a high prevalence of MAFLD but also includes ACLD, which is a more realistic clinical scenario in the application of liver fat quantification methods. This study performed a comprehensive evaluation of patients to assess the effect of altered liver texture due to inflammation and fibrosis on liver fat quantification. Our study evaluated a mixed population cohort, unlike the studies by Roberto, et al. [12], who evaluated patients with < S2 grade, and by Dillman, et al. [13] and Labyed, et al. [9], who evaluated only obese patients.

Results of current study show a 56.6%, 53.1%, and 75% perfect agreement in the measurements between the two systems in the overweight, obese, and normal categories respectively, with major differences observed being 18.9%,15.6% and 0% respectively. Our study is the first to show steatotic grade differences between two systems with one grade or less differences seen in 91.2% of cases and more than one grade in the remaining 8.8%, which suggests that both systems are reliable for clinical use in normal, overweight, and obese patients, similar to the results reported by Dillard, et al. [13] and Labyed, et al. [9]. There was a measurement bias with slight underestimation of fatty grade by Aplio with mean bias difference of -0.29 with 95% CI of1.96SD with these differences being clinically insignificant. The explanation for these differences lies in the systematic differences in the measurement techniques of both systems, namely Aplio, using AC-based imaging with no set ROI point from the surface of the liver, whereas Sequoia uses AC with the BSC technique with a fixed 1.5cm distance of ROI from the liver capsule. Furthermore, these differences were much smaller than the 4% difference between UDFF and MRPDFF in obese patients reported by Dillman, et al [13]. Our study also showed no strong association between BMI, age, and fatty-grade, which is similar to the results of Ferrolia et al. [4] and Labyed, et al. [9]. The reason for this is likely due to the predominance of patients with a high BMI in the present cohort, with only four normal BMI patients. It would also be interesting to discuss the results of the confounding variables for discordance in the measurements in this study.

SCD, which reflects increased subcutaneous fat, emerged in the current study as the major factor accounting for 25-30% discordance. Song, et al [14] also pointed out that SCD strongly correlated with hepatic steatosis than the traditional obesity metric of BMI but did not gave any percentage of discordance. Our study clearly showed high effect of 66.7% 4th quartile of SCD on both S2 and S3 fat grades, while the Q1-Q3 quartiles had an overall (4-11%) weak relationship effect. Diagnostic analysis of the SCD Quartile showed a sensitivity of 76% at a cut-off value of 2.1cm and has not been documented earlier. This finding has clinical implications, and patients with increased subcutaneous fat, but not obesity, are also candidates for measurement discordance in fatty grades by the systems. Our study also highlights the importance of combination of SCD with BMI in the multivariate analysis model, where addition of high BMI raised the means odds ratio for discordance to 1.9. This suggests that patients with both visceral and subcutaneous fat are twice as likely to show variations in intersystem measurements; hence, longitudinal studies of such patients for fat quantification must be performed on the same systems. Our study clearly ruled out the presence of inflammation and fibrosis as confounding variables, as hypothesized by Baek, et al. [15]. Current study also had outlier cases four of which had raised iron liver levels demonstrated on MR-PDFF and were falsely labelled as S3 grades on Sequoia and as S1 grade on Aplio and were patients of Dysmetabolic Iron Overload Syndrome (DIOS) [16-18] a condition with increase in iron stores associated with components of metabolic syndrome and in the absence of an identifiable cause of iron excess. We hypothesize that increased iron in liver parenchyma causes more back scatter resulting in false high fat percentage calculation on sequoia which was not the case in AC algorithm in Aplio. Further we did not observe any statistically significant differences in SWD and SWE values in the concordance and discordant groups with liver inflammation or fibrosis.

Conclusion

The majority (91%) of measurements were within one grade; however, there was a negligible negative bias in the study, which suggests that Aplio had lower values than Sequoia but was clinically acceptable given that most differences were within one grade. Cases with more than one grade difference (9%) may require additional evaluation owing to systematic bias in the measurements. S3 obese categories of patients may require additional evaluation; liver ferritin may be the main confounding factor, and the same machine should be recommended for longitudinal monitoring. SCD was observed as the main factor for discrepancies rather than BMI alone, and had a significant correlation (p=0.001) with a magnitude of 0.40. Aplio showed a higher discrepancy at cut off of 2.3cm while it was 2.52cm for sequoia with no discrepancy seen at 2.06cm. The study proposed a cut of 2.1cm for increased discrepancies with an OR of 1.9 and a sensitivity of 76%.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- (2016) EASLEASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 64(6): 1388-1402.

- Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, et al. (2016) Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 64(1): 73-84.

- Barr RG (2019) Ultrasonography of diffuse liver disease, including elastography. Radiol Clin North Am 57(3): 549-562.

- Ferraioli G, Soares Monteiro LB (2019) Ultrasound-based techniques for the diagnosis of liver steatosis. World J Gastroenterol 25(40): 6053-6062.

- Tang A, Desai A, Hamilton G, Tanya Wolfson, Anthony Gamst, et al. (2015) Accuracy of MR imaging-estimated proton density fat fraction for classification of dichotomized histologic steatosis grades in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Radiology 274(2): 416-425.

- Chan WK, Nik Mustapha NR, Mahadeva S (2014) Controlled attenuation parameter for the detection and quantification of hepatic steatosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 29(7): 1470-1476.

- Chan WK, Nik Mustapha NR, Mahadeva S, Wong VW, Cheng JY, et al. (2018) Can the same controlled attenuation parameter cut-offs be used? be used as the M and XL probes for diagnosing hepatic steatosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 33(10): 1787-1794.

- Chen CF, Robinson DE, Wilson LS, Griffiths KA, Manoharan A, et al. (1987) Clinical sound speed measurements in the liver and spleen in vivo. Ultrason Imaging 9(4): 221-235.

- Labyed Y, Milkowski A (2020) Novel method for ULTRASOUND-DERIVED fat fraction using an integrated phantom. J Ultrasound Med 39(12): 2427-2438.

- Ferraioli G, Maiocchi L, Raciti MV, Tinelli C, De Silvestri, et al. (2019) Detection of liver steatosis with a novel ultrasound-based technique: A pilot study using MRI-derived proton density fat fraction as the gold standard. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 10(10): e00081.

- Jesper D, Klett D, Schellhaas B, Pfeifer L, Leppkes M, et al. (2020) Ultrasound-Based Attenuation Imaging for the Non-Invasive Quantification of Liver Fat-A Pilot Study on Feasibility and Inter-Observer Variability. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med 8: 1800409.

- De Robertis R, Spoto F, Autelitano D, Guagenti D, Olivieri A, et al. (2023) Ultrasound-derived fat fraction for detection of hepatic steatosis and quantification of liver fat content. Radiol Med (Torino) 128(10): 1174-1180.

- Dillman JR, Thapaliya S, Tkach JA, Trout AT (2022) Quantification of Hepatic Steatosis by Ultrasound: Prospective Comparison With MRI Proton Density Fat Fraction as Reference Standard. Am J Roentgenol 219(5): 784-791.

- Song D, Wang P, Han J, Chen H, Gao R, et al. (2024) Reproducibility of the ultrasound-derived fat fraction for measuring hepatic steatosis. Insights Imaging 15(1): 254.

- Baek J, Kaffas AE, Kamaya A, Hoyt K, Parker KJ (2025) Multiparametric quantification and visualization of liver fat using ultrasound. Physics, arXiv.

- Dos Santos Vieira DA, Hermes Sales C, Galvão Cesar CL, Marchioni DM, Fisberg RM (2018) Influence of Haem, Non-Haem, and Total Iron Intake on Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components: A Population-Based Study. Nutrients 10(3): 314.

- Ameka M, Hasty AH (2022) Paying the Iron Price: Liver Iron Homeostasis and Metabolic Disease. Compr Physiol 12(3): 3641-3663.

- Fernandez M, Lokan J, Leung C, Grigg A (2022) A critical evaluation of the role of iron overload in fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 37(10): 1873-1883.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.