Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Explosive Outbreak of Dalbulus Sp. and Corn Stunt Disease Associated to Climatic Variations in the Cochabamba Inter-Andean Valley, Bolivia

*Corresponding author: Coca Morante M, Plant pathology laboratory. Phytotechnician department. Agricultural and Livestock Sciences Faculty. Universidad Mayor de San Simón. Cochabamba, Bolivia, Email: m.cocamorante@umss.edu.bo

Received: March 11, 2025; Published: March 20, 2025

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2025.26.003431

Abstract

Corn (Zea mays L.) is a cereal that is traditionally grown in the inter-Andean valleys of Bolivia. Cochabamba inter-Andean Valley - 2400 to 2700 meters above sea level - includes lower, central and high valleys, and diversity local varieties are grown for consumption such as “Choclo” and grain. “Hualtaco” white corn is the most cultivated variety. Due the climate variations -temperature and rainfall-, water and intensive use of technology, winter corn - July to December - cultivation was promoted throughout the Cochabamba valley, generating an early planting different from the traditional summer planting - November to April. This led to a gradual proliferation of Dalbulus sp., as well as the emergence of the stunt or “Palmarado” disease corn. Stunt corn disease, presenting symptoms such as reddening of the leaves, short internodes, proliferation of ears and dwarfism, is Caused by Spiroplasma (CSS) and/ or phytoplasma (MBSP). According to technical reports, since the 1960s, Dalbulus sp. had a proliferation process and stunt disease began to be reported in the 1970s. Approximately, since the 1980s, in the lower and central valley, Hualtaco corn variety for “Choclo” stopped being cultivated due to the stunt disease corn. In the high valley, in a similar process, both Dalbulus sp and stunt disease corn were spread. In 2008, it was reported that Dalbulus and stunt disease corn were scattered throughout the valley. In 2018, was recorded severe damage to the “Choclo” production in communities in Toco municipality. In 2024, an outbreak was recorded with severe losses in the same communities in Toco and Punata municipalities, and other high valleys. In conclusion, Dalbulus sp and the stunt or “Palmarado” corn disease are widespread throughout the valley, due to the change in the cropping system and climatic variations causing severe losses in corn production.

Keywords: Bacterial disease, Traditional pattern, Native varieties

Introduction

In Bolivia, a diversity native corn (Zea mays L.) varieties -143 races- are traditionally grown, typical of the inter-Andean valleys -2000 to 3000 to the highlands -3800 meters above sea level-, for fresh consumption as “choclo” and grain as “mote” -grain cooked in a pot- [1,2]. More than 400 thousand hectares are cultivated in Bolivia, but 150 thousand hectares are cultivated in the extensive agriculture of eastern Bolivia with hybrid varieties and 45 thousand hectares are cultivated approximately to food security in the valleys of Cochabamba (INE 2024). Most native varieties cultivated are: Culli (Figure 1A), Ch’uspillo, Uchuquilla, Huillcaparu, Chuncula and yellow corn and white corn [1,3,4]. Cochabamba Valley is differentiated by the lower valley -Quillacollo, Vinto, Sipe sipe and Capinota municipalities, an average of 2400 meters-, central valley -Cercado, Tamborada, Colcapirhua and Tiquipaya municipalities, an average of 2500 meters-, and the high valley -Punata, Sacaba, San Benito, Tarata, Arbieto, Cliza and Toco municipalities, average 2700 meters-. “White corn” variety known as “Hualtaco” (Figure 1B) [5] is the most cultivated for consumption as “Choclo” and has “Hualtaco” variants one is small grain -early- and large grain other -late-. One of the limiting factors in corn production in these valleys is diseases [6], reports Phyllachora maydis Maubi, affecting corn in Coroico locality, La Paz department. In a study of Bolivian corn germplasm [2], mentions the evaluation for rusts, helminthosporiosis and smut [7] made one of the first systematic records of plant diseases in Bolivia. It mentions 15 causal agents of common corn diseases, such as smut (Ustilago maydis), rust (Puccinia sorghi), bacteria (Pseudomonas alboprecipitans), nematodes (Trichodorus christiei and Tylenchorynchus sp) and leaf spots (Cladosporium sp., Helmintosporium sp., etc.). Subsequently [8], in an updated version of corn diseases, mention same and additional diseases and causal agents of corn diseases in Bolivia, but, for the first time, they mention viral diseases.

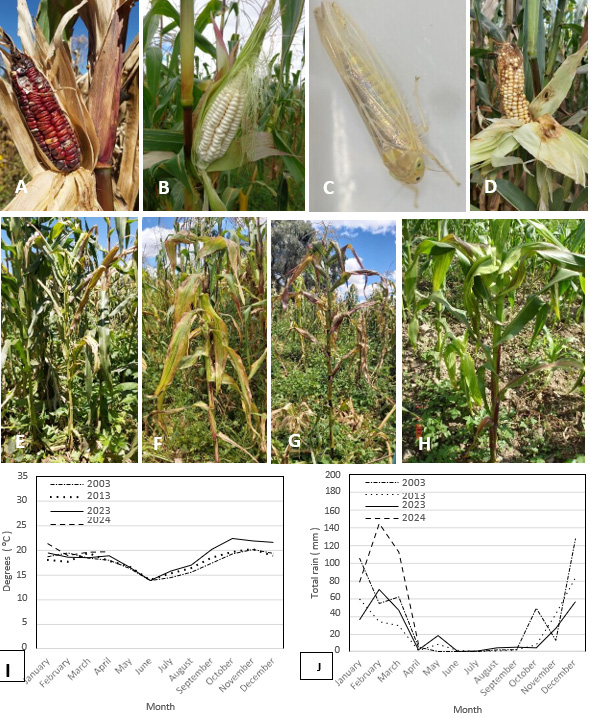

But viral corn diseases began to be reported since 1960s. Candia (1965) (cited by Bascope 1977), mentions vectors of the “Palmarado” virus corn disease as if Palmarado of corn were a viral disease [9] mentions Dalbulus sp (Figure 1C), which transmits various viral diseases. Until these years, “Palmarado” disease was associated with a disease caused by viruses, and, apparently, associated with transmission by Dalbulus sp. (Figure 1C). [8], report for Bolivia, the viral disease “leaf curl” -unconfirmed-, mosaic -probably SCMV- and “fine stripe” of corn. Subsequently [10] reported that corn stunting, “central meza race” in Mexico, known as “Palmarado” of corn in Bolivia, is caused by a Mycoplasma type microorganism - today called Phytoplasma - and transmitted by the leafhopper Dalbulus maidis (Figure. 1C). At present, it is known that Dalbulus sp. is a vector of corn diseases, which include “Corn Stunt Spiroplasma” (CSS) -, “Severe corn stunt” or “Maize Bushy Stunt Phytoplasm” (MBSP) -, caused by a phytoplasma [11], and “rayado fino virus” -Maize Rayado Fino Virus, MRFV- [12]. Both bacterial diseases - spiroplasm and phytoplasm - cause similar symptoms of stunting (Figure 1D), formation of short internodes, proliferation of small corns, linear yellowing and reddish coloration of the leaves and collapse of the male inflorescence, known as “Palmarado” disease or corn palm in the Cochabamba Valley.

Emerging Leafhopper Populations Associated to Early Planting and Climatic Change Effect

Early or winter sowing - July/December - was a traditional practice in the lower valley, small scale. Climate, irrigation water and market were factors that motivated this planting. Climate is temperate, typical of the inter-Andean valleys. Water comes from the Tunari mountain range which favors intensive agriculture. Tunari mountain range has several water basins that allow surface and underground water to be captured. With creation of irrigation system No. 1 “La Angostura” dam - law of January 9, 1945 - since 1945, irrigation improved, and helped consolidate winter planting with the “Hualtaco” variety (Figure 1B), apart from late or summer sowing -October/November-, which is the most important. Geographical location and roads that pass through these valleys also favored the supply of “choclo” to the local market and west and east of Bolivia. The impacts were an increase in “corn” production -approximately from 2% to 5% of the almost 45,000 hectares cultivated- [2] INE 2024, and improvements in the income of producers.

With the “Green Revolution” technology emergence, the use of chemical fertilizers, herbicides, insecticides and other agro inputs intensified, causing a selective impact on pest management. This transformation process of the corn cultivation system in these valleys, in the long term, generated a “phytosanitary” complex caused by pests -insects and diseases-, such as the emergence of the leafhopper -Dalbulus sp.- (Figure 1C). 1970s, some pests began to be reported as harmful to corn crops. [9], reports that “…in the valleys, the insects that cause the greatest damage to corn crops are the earworm -Heliotis sp.- (Figure 1D) and Dalbulus sp (Figure 1C), that transmits various viral diseases. This was one of the first reports where Dalbulus sp. began to stand out as an insect pest and vector (Figure 1C). Climatic variations were an additional factor in insects’ proliferation such as the “Dalbulus sp.” (Figure 1C). Global warming, prolonged droughts, changes in atmospheric CO2 concentrations, climate disruptions, and other variations - droughts, hailstorms, and frosts - have affected the reproduction, survival, development and dispersal of crop pests [13].

In the Cochabamba Valley, according to records of temperatures - maximum and minimum - and average precipitation of the last 20 years, the average temperature per year recorded 2003 = 17.7oC to 2023 = 18.7oC (Figure 1I), and, total precipitation (mm) per year decreased, from 2003=422mm to 2023=270 mm (Figure 1J). This means a new climate pattern formation with a trend of temperatures increasing -from 17.7 to 18.7oC- and rainfall decreasing -from 422 in 2003 to 270mm in 2023-. [14]. In the medium and long term, these temperature and rainfall variations-droughts and rainfall decreased - have completed accelerating a new behavioral pattern emergence for the Dalbulus sp proliferation. In 2008, a study revealed the widespread distribution of Dalbulus sp, throughout the Cochabamba valley [4].

Van Nieuwenhove, et al. (2015), [15], indicate that the vector is unlikely to develop permanent populations in temperate areas of the American continent because there is no availability of host plants for extended periods, with mean temperatures below 17oC. In the Cochabamba valley conditions, 1970s, there are two planting systems during a year -winter and summer cultivation-, therefore, there are host and alternate host plants available, another hand, there is an increase in temperature - from 17.7 to 18.7oC - and a reduction in rainfall - from 422 in 2003 to 270 mm in 2023 - (Figure 1I-J). According to our data (Figure 1I-J), the months from August -17oC- to December-21.6oC - of 2023, were the hottest and driest -August 4.07 mm and December 56.89 mm- of the last 20 years. August to December is coincident with vegetative growth of the winter sowing and harvesting of “corn”, therefore, there are conditions for the proliferation of Dalbulus sp., which will “greatly” affect the summer sowing - November - which is the most important sowing [16] indicate in the seasonal and vertical distribution of Dalbulus maidis in Brasilian corn fields that the population of D. maidis in the dry season was much larger than in the rainy season. Alternate host have a rol complementary in the population of D. maidis [17], Vicia faba L., Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don, Raphanus sativus L., Sinapis alba L. (Brassica hirta Moench) and Spinacia oleracea L. are also reported as experimental hosts for CSS. On another hand, [18], it is known to feed on several other monocotyledonous plant species such as gamagrass and Johnson grass in the absence of corn and teosintes and there is evidence of D. maidis surviving for several months in the absence of host plants in non-irrigated maizefree fields. Finally, Arthropod vectors play an important role in the spread of plant pathogenic spiroplasmas, and thus it is important to understand how they interact with their vectors and cause disease epidemics in agricultural settings and D. maidis is considered a serious pest of corn in Mexico, the Caribbean basin, and Central and South America, especially because of its competence in phytopathogen transmission and associated yield loss [18].

Figure 1: Corn, grain and forage crops grown in the Cochabamba valley. A: Cob Maturity state of culli variety maize; B: Cob in “Choclo” state, Hualtaco variety; C: Adult stage of Dalbulus sp.; D: Cob affected by Heliotis sp., Forage Compound 10 variety. Symptoms of stunt disease in Hualtaco and forage corn. E-G: Choclero corn stunting, var. Hualtaco; Linear yellowing and reddening of leaves; H: Stunt disease in forage variety Pool 12; I: Temperature variations; J: Rain variations.

Outbreak Corn Stunt Disease

Corn stunt disease in the Cochabamba Valley occurred in two different times -1970-1980 in the lower valley and 2018-2024 in the high valley, causing severe losses in production. In the lower valley, since the 1980s, the white corn “Hualtaco” production for consumption as “Choclo” began to be drastically reduced. Currently, due to losses caused by corn stunt or “Palmarado” it is cultivated in isolation. Instead, forage corn such as Compound 10 (Figure 1D), Pool 12, UMSS V- 107, etc. is cultivated -all of Mexican origin-, including Cuban-type varieties. Losses caused by this disease in “Choclero” corn can reach 100% of production. “Choclero” varieties such as “Hualtaco” corn are more susceptible compared to forage, hard or hybrid corn.

In the high valley, Dalbulus sp. and stunt disease had a similar process to that of the lower valley, especially due to their traditional relationship, for example, in agriculture, the exchange seed or the continuous and permanent movement of “chala”. This process could be related to the dissemination of Dalbulus sp and the stunt disease. Likewise, the winter sowing increase with Hualtaco corn for “Choclo” could also be related to the dissemination of Dalbulus sp and stunt disease. Irrigation water in the higher valley municipalities was traditional, although have small rivers or temporary springs. But, since the ‘80s, Non-Governmental Organizations -NGOs- and the state government, invested resources in drilling wells, until after more or less, 20years, they were saturated with water wells, currently generating overload. in the higher valley groundwater system.

Irrigation system growth in High Valley increased the winter corn cultivated area intensified the chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and insecticides use, as well as increased the supply of “choclo” for the December month. Currently, there are two seasons of corn cultivation in the higher valley - winter and summer -more importantly-. This two-epoch system, in the long term, also generated conditions for the Dalbulus sp proliferation and stunt disease. According to knowledge farmers, the stunt disease was present for a long time, but without relevance. In 2008, it was reported that Dalbulus sp. and stunt corn disease, are distributed in the lower and higher Valley of Cochabamba [4]. In 2018, severe damage to corn production caused by stunt corn disease was recorded in the Incachaca community Toco municipality. This year -2024-, in the same communities in the influence area of community “Incachaca”, toco municipality, severe losses were recorded. In Punata municipality, severe losses were recorded in corn plantations “Hualtaco”, “Ch’uspillo”, “Culli”, “Uchukilla”, etc. It is estimated that some four thousand producers were affected, approximately 1,500 hectares of summer planting with losses between 80 to 100% of production corn. Considering that they are small farmers, economic losses are significant and the impact is relevant because production is destined entirely for self-consumption and the local market. Until now, insect corn control in the inter-Andean valleys has mainly been directed against Heliotis sp.-, but, based on this new pest corn context, different control management strategies both Heliotis and Dalbulus sp must be implemented.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the stunt or “Palmarado” corn disease, is characterized by presenting symptoms such as plant stunting, internodes short, small ears proliferation, apical leaves reddening and favored by early planting times - June/July - and late sowing -Novemberof corn, technology intensive use, overload of irrigation projects, climatic variations and local and national market demand, caused a high proliferation of -Dalbulus sp.- and explosive outbreak corn stunt disease, causing severe losses in the production of “Choclo”, and probably, in other Cochabamba valley municipalities and other regions of Bolivia [19,20-24].

Acknowledgment

The author thanks the producer’s irrigators’ associations and municipal technicians of the Toco and Punata municipalities of Cochabamba department, for their cooperation in the production fields evaluations in different communities. To Ing. Hernan Campos Garvizu, Head of the Corn and Sorghum Forage Program at the Forage Research Center (CIF) [19] “La Violeta” and Ing. Emigdio Cespedes Salazar, research professor at Agricultural and Livestock Sciences Faculty -FCAyP-, for his comments and suggestions.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Cutler HC (1949) Races of maize in south america. Journal of Agriculture. Official organ of the Faculty of Agronomic Sciences of the Universidad Mayor de San Simó Cochabamba, Bolivia pp: 4-19.

- Quiroga Gómez J (1963) Study of Bolivian maize germplasm. Thesis presented to obtain the degree of Agricultural Engineer. Faculty of Agronomy Sciences. Universidad Mayor de San Simó Cochabamba, Bolivia pp. 500.

- Bascopé Quintanilla JB (1973) Trial of six varieties of corn for corn in four planting seasons in two localities of the central valley of Cochabamba. Degree thesis. Faculty of Agricultural Sciences "Martin Cárdenas H.". Universidad Boliviana Mayor de San Simó Cochabamba, Bolivia: pp. 75.

- García Escobar J (2008) Incidence of palmarado and fine streak virus vs populations of Dalbulus maidis De Long & Wolcott in maize plants (Zea mays ). Bachelor's thesis.

- Cárdenas M (1944) Plant Health. pp: 39-40. Agriculture Magazine. Official organ of the Higher School of Agronomy of the Autonomous University of Cochabamba. University Press. Cochabamba, Bolivia: 46 pp.

- Cárdenas M (1944) Experimental corn fields at the "Las Cuadras" farm. pp: 43-45. Agriculture Magazine. Official organ of the Higher School of Agronomy of the Autonomous University of Cochabamba. University Press. Cochabamba, Bolivia: 46 pp.

- Ellis K C (1977) Index of plant diseases in Bolivia. Consortium for international development. Working paper No 15/77. La Paz, Bolivia: 25p.

- Otazu V, Brown WM, Mery H from Quiton (1982) Plant diseases in Bolivia. Ministry of Peasant and Agricultural Affairs. Bolivian Institute of Agricultural Technology-International Partnership for Development. Cochabamba, Bolivia pp. 30.

- Avila L G (1971) Current status of maize production and improvement in Bolivia. Fourth conference on maize in the Andean zone. ICA-CIAT. Palmira, Colombia pp. 25-27.

- Bascopé Quintanilla JB (1977) Causal agent of the so-called "Central Table Race" of corn stunting. National School of Agriculture. Chapingo Postgraduate College, Mexico pp. 55.

- Delia Gamarra, Charo Milagros Villar, Torres Suarez G, Ingaruca Esteban WD, Nicoletta Contaldo, et al. (2022) Diverse phytoplasmas associated with maize bushy stunt disease in Peru. Eur J Plant Pathol 163: 223-235.

- Gamez R, Leon P (1985) Maize Rayado Fino and Related Viruses. p: 213-233. in: The plant viruses volume 3 polyhedral virions with monopartite RNA genomes. koenig R. (ed.). Plenum Press New York and London.

- Subedi B, Anju Poudel, Samikshya Aryal (2023) The impact of climate change on insect pest biology and ecology: Implications for pest management strategies, crop production, and food securit ScienceDirect Journal of Agriculture and Food Research journal. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 14: 100733.

- Time (2024) World weather data. https://www.tutiempo.net/clima/11-2014/ws- 852230.html (12/05/2024).

- Van Nieuwenhove GA, Frías Eduardo A, Virla Eduardo G (2015) Effects of temperature on the development, performance and fitness of the corn leafhopper Dalbulus maidis (DeLong) (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae): implications on its distribution under climate change. Agricultural and Forest Entomology.

- Lowell R Nault (1975) Maize Bushy Stunt and Corn Stunt: A Comparison of Disease Symptoms, Pathogen Host Ranges, and Vectors. Phytopathology 70:659-662. Meneses Aurélio R, Ranyse B Querino, Oliveira Ch M, Aline H.N. Maia, and Silva P.R.R. 2016.

- Tsai J H, Miller J W (1995) Corn Stunt Spiroplasma. Fla. Dept. Agric. & Consumer Services.

- Jones Tara kay L, Medina Raúl F (2020) Corn Stunt Disease: An Ideal Insect-Microbial-Plant Pathosystem for Comprehensive Studies of Vector-Borne Plant Diseases of Corn. Plants 9(6): 747.

- Forage Research Center "La Violeta" (CIF) (2006) Forage maize: for the Andean valleys and the subtropics of Bolivia. Forage production training bulletin series. Cochabamba, Bolivia pp. 4.

- Gamarra DG, CM Villar, GT Suarez, WDI Esteban, E CC Lozano (2022) Center for Plant Molecular Biology Research, Universidad Nacional del Centro del Peru, Av. Mariscal Castilla N°3909, El Tambo, Huancayo, Peru N. Contaldo: A. Bertaccini Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, Alma Mater Studiorum - University of Bologna, Viale G. Fanin, 40, 40127 Bologna, Italy / Published online: 5 February 2022 Eur J Plant Pathol 163: 223-235.

- Faculty of Agricultural and Livestock Sciences. Universidad Mayor de San Simó Cochabamba, Bolivia pp. 60.

- Seasonal and vertical distribution of Dalbulus maidis (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) in Brazilian corn fields. Florida Entomological Society.

- Santa Olga Cacciola, Assunta Bertaccini, Antonella Pane and Pio Maria Furner (2017) Spiroplasma spp.: A Plant, Arthropod, Animal and Human Pathogen. In: Citrus diseases. Chapter two. Harsimran Gill and Harsh Garg (Eds.).

- Division of Plant Industry. Plant Pathology Circular No. 373.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.