Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Laryngeal Symptoms and Findings in Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems Users

*Corresponding author: Dr. Eduardo López-Orozco, Otolaryngology private practice, Niños Héroes 1921-9, Guadalajara, México.

Received: April 08, 2025; Published: April 14, 2025

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2025.26.003469

Abstract

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDSs) are a relatively new device that have been demonstrated to have toxicologic effects. Laryngeal exposure to ENDSs in animals and experimental models has shown hyperplasia, metaplasia and inflammatory molecules. This was a cross-sectional study in which volunteers were assessed both with an indirect laryngoscopy and with validated questionnaires. Volunteers answered the Reflux Symptoms Index (RSI), Voice Handicap Index-10 (VHI-10), and Eating Assessment Tool-10 (Eat-10). Laryngoscopies were assessed using Reflux Finding Score (RFS). We included 11 ENDSs users, and 5 healthy volunteers. Mean use of ENDSs was 11.64 uses per day for 3.23 years. RSI was 13.82 (0-31, SD 8.98) in the ENDSs user group, vs 0 (0-0, SD 0) in the non-user group, this finding was statistically significant (p 0.0002). EAT-10 score was 1.82 (0-10, SD 2.93) in the ENDSs users group, while it was 0 (0-0, SD 0) in the non-user group, this finding was statistically significant (p 0.033). RFS was 7.09 (2-12, SD 3.03) In the ENDSs users group, while it was 5.6 (3-9, SD 2.7) in the non-users, this finding was not statistically significant (0.179). We can conclude there is higher prevalence of laryngeal irritation symptoms in ENDSs users, larger sample sizes and more studies with a larger follow up will be required to establish a clear link.

Keywords: Electronic nicotine delivery systems, E-cigarettes, vape, Larynx, Laryngopharyngeal reflux

Introduction

The terms electronic-cigarettes, “e-cigs”, “vapes” or Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDSs) refer to products that heat a chemical solution (that consists mainly of propylene glycol, glycerol and nicotine), and deliver it to the user, mainly through the airways [1]. They were marketed as a healthier alternative to tobacco, calling them “cleaner”, and even featuring doctors in their marketing [2].

However, as ENDSs’ popularity has increased, so have the publications linking them to adverse health effects. ENDSs contain mostly propylene glycol and glycerol (80-94%), which act as solvents, and which have been proven to be airway irritants. The active ingredient is nicotine, which is often accompanied by benzoic or citric acid. Other components include metals (nickel, manganese, zinc, copper, iron and arsenic), flavoring agents (ethyl maltol, ethyl vanillin menthol) and solvents (formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein and glycoxal) [3]. Toxicologic effects similar to smoking have been shown with exposure to ENDSs such as disruption to epithelial barriers, oxidative stress, cytotoxicity and DNA damage [4].

Literature regarding the effects of ENDS use is more limited in the otolaryngologic area, with most publications reporting upper- respiratory symptoms related to its use, such as throat irritation, discomfort, cough, nasal congestion and sinusitis [5]. Basic research has shown that exposure of human engineered vocal fold mucosae to electronic cigarette vapor extract induced cellular damage of luminal cells, disrupting homeostasis and innate immune responses [6]. Animal research has also shown that exposure to ENDS for 4 weeks caused hyperplasia and metaplasia of the laryngeal mucosa of rats; however, this finding was not statistical significant [7]. An increase in laryngeal IL-4 has been found in murine models exposed to nicotine products [8]. Nevertheless, to our knowledge there are no studies performed in current ENDSs user evaluating their larynx and their symptoms.

Objective

The objective of this study is to perform indirect laryngoscopic examinations in ENDSs users, to describe their findings, and to compare them with non-users.

Material and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study in which healthy volunteers in the Guadalajara, Mexico area who admitted to using ENDSs were recruited. Volunteers who do not use ENDSs were recruited as a control group. After their informed consent, a questionnaire was administered. To quantify the use of ENDSs we used the first item of the Penn State Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index [9], which was demonstrated to be a significant predictor of actual frequency of e-cig puffs taken, after comparing the users’ self-reported scores with multiple observations [10]. We utilized a translated, adapted and validated Spanish version [11].

We also assessed ENDSs users’ self-reported symptoms regarding voice, swallowing and reflux symptoms, using scales that have been translated and validated in Spanish. Belafsky’s 9-item Reflux Symptom Index [12] was used to assess whether the participants experienced any reflux-associated symptom; we employed a validated Spanish translation (13). To assess the vocal quality, we employed the Voice Handicap Index-10 (VHI-10) developed by Rosen to screen for voice alterations [14]; we utilized a validated Spanish translation [15]. Finally, we screened for any dysphagia symptom using the 10-item self-administered questionnaire Eating Assessment Tool-10 [16] in a Spanish translated and validated version [17].

Afterwards, an endoscopic examination of the larynx and upper airways was performed using a flexible fibreoptic chip-on-the-tip endoscope. The endoscopic examinations were performed by the same otolaryngologist (ELO). The endoscopic examinations were analyzed and scored blindly by the same laryngologist (AGMR) using the Reflux Finding Score, an 8-item clinical severity score, which assigns scores to subglottic edema, ventricular obliteration, laryngeal erythema/hyperemia, vocal fold edema, diffuse laryngeal edema, posterior commissure hypertrophy, granulation tissue and thick endolaryngeal mucus [18].

Results were pooled in Microsoft Excel, which was used to obtain descriptive statistics. Paired t-test was performed to determine whether a statistical significant difference was present between the ENDSs users and the non-users. Statistical significancy at a confidence interval of 95% was determined if the p value was less than 0.05. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to correlate the ENDSs exposure (calculated by multiplying ENDSs used per year times years used) with RSI, VHI-10, EAT-10 and RFS scores.

Results

Results are summarized in Table 1. We included 11 ENDSs users and 5 non-users to serve as controls. The mean use of ENDSs was 11.64 uses per day with a range from 1 to 50 uses per day (each use equals to 15 puffs or 10 minutes of use). Users have used ENDSs on average for 3.23 years, with a range from 2 to 5 years. Every volunteer was otherwise healthy and denied tobacco use.

Table1: Results. ENDSs=Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems; SD=Standard Deviation; RSI=Reflux Symptoms Index; VHI-10=Voice Handicap Index 10; EAT-10=Eating Assessment Tool 10; RFS=Reflux Findigs Score; (range)

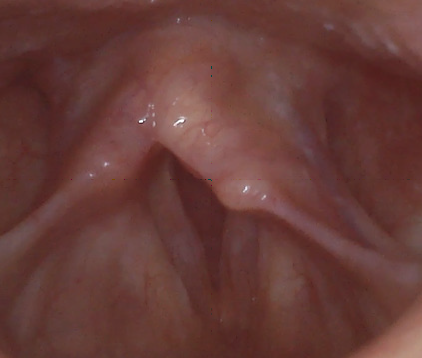

The average Reflux Symptoms Index (RSI) score on ENDSs users was 13.82 (range 0-31, SD 8.98) compared to 0 on non-users (range 0, SD 0), this result was statistically significant with a p value of 0.0002. The average Voice Handicap Index-10 (VHI-10) on ENDSs users was 1.45 (range 0-6, SD 1.97), while it was 1.8 (range 0-9, SD 4.02) on non-users; this was non-statistically significant with a p value of 0.8626. Finally, the average Eating Assessment Tool-10 (EAT-10) score for ENDSs users was 1.82 (range 0-10, SD 2.93), the mean score for non-users was 0 (range 0, SD 0); this difference was statistically significant with a p value of 0.033157384. After performing the laryngoscopic examinations, the average Reflux Finding Score in ENDSs users was 7.09 (range 2-12, SD 3.03), while it was 5.6 (range 3-9, SD 2.7) in non-users; p value was 0.17. Among the ENDSs users there were two patients with moderate ventricular band hypertrophy and one with vocal cord ectasia and a vocal cord varix. Illustrative findings are included in Figure 1 and 2.

Figure1: Laryngoscopic image showing a larynx with vocal cord ectasia, mild vocal cord edema, thick mucus, and mild posterior commissure hypertrophy and a vocal cord varix.

Figure2: Laryngoscopic image showing hyperemia, abundant mucus and posterior commissure hypertrophy.

Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.2839 for RSI, 0.5627 for VHI-10, -0.1196 for EAT-10, and -0.2387 for RFS.

Conclusions

ENDSs users presented statistically significant higher scores in both the Reflux Symptoms Index and the Eating Assessment Tool- 10. This indicates that the exposure to the ENDSs may be associated to laryngeal irritation symptoms such as hoarseness, excess mucous, cough, throat clearing and dysphagia. ENDSs users had a higher RFS score after laryngeal examination. The average for ENDSs users was 7.09, while the average for non-users was 5.6. This was not statistically significant, which could be explained by the sample size. Nonetheless, the ENDSs user group did have other pathologic findings such as ventricular band hypertrophy and vocal cord ectasia and vocal cord varices. Pearson correlation coefficient did not show strong correlations between time and intensity of ENDSs use and RSI, EAT-10 and RFS. However, it did show a slightly stronger correlation between time and intensity of ENDSs use, and VHI-10. This could imply that the higher the exposure to ENDSs, the worse the self-reported voice perception.

Discussion

The larynx of the ENDSs tended to have higher RFS scores and more inflammatory findings than their non-user counterparts. Nevertheless, this finding did not achieve statistical significancy. This could be due to a couple of factors. First of all, ENDSs are a relatively new product, and users have not been exposed for a long time: the average length of use of ENDSs was 3.23 years, with the longest user having used them for 5 years. A longer follow-up could reveal the long-term effects of ENDSs. Second, our study was limited to questionnaires and a laryngologic exam. We hypothesize that a laryngeal biopsy could reveal more microscopic inflammatory or dysplastic changes in the larynx; however, we could not justify biopsying healthy patients. Thirdly, the sample size was relatively small.

An argument could be made regarding the utilization of the reflux finding score and the reflux symptoms index, both scales designed specifically for reflux-related laryngeal alterations. However, those are the only validated and objective scales designed for laryngeal irritation. Since most of the ingredients contained in ENDSs are known airway irritants, we hypothesized that irritation similar to that generated by reflux would be found. Linking cigarette-smoking with disease was a long process that required a multitude of studies, and millions of patients [19]. This publication’s intention is not to establish a link between ENDSs and adverse laryngeal effects, but to shed a light on some of the effects ENDSs may have in the laryngeal inflammation. Ultimately more and larger studies will be required.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA (2014) E-Cigarettes: A Scientific Review. Circulation 129(19): 1972-1986.

- Grana RA, Ling PM (2014) “Smoking Revolution” A Content Analysis of Electronic Cigarette Retail Websites. Am J Prev Med 46(4): 395-403.

- Bonner E, Chang Y, Christie E, Colvin V, Cunningham B, et al. (2021) The chemistry and toxicology of vaping. Pharmacol Ther 225: 107837.

- Shields PG, Berman M, Brasky TM, Freudenheim JL, Mathe E, et al. (2017) A review of pulmonary toxicity of electronic cigarettes in the context of smoking: A focus on inflammation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26(8): 1175-1191.

- Soo J, Easwaran M, Erickson DiRenzo E (2023) Impact of Electronic Cigarettes on the Upper Aerodigestive Tract: A Comprehensive Review for Otolaryngology Providers. OTO Open 7(1): e25.

- Lungova V, Wendt K, Thibeault SL (2022) Exposure to e-cigarette vapor extract induces vocal fold epithelial injury and triggers intense mucosal remodeling. Dis Model Mech 15(8): dmm049476.

- Salturk Z, Çakir Ç, Sünnetçi G, Atar Y, Kumral TL, et al. (2015) Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery System on Larynx: Experimental Study. J Voice 29(5): 560-563.

- Ha TAN, Madison MC, Kheradmand F, Altman KW (2019) Laryngeal inflammatory response to smoke and vape in a murine model. Am J Otolaryngol 40(1): 89-92.

- Foulds J, Veldheer S, Yingst J, Hrabovsky S, Wilson SJ, et al. (2015) Development of a questionnaire for assessing dependence on electronic cigarettes among a large sample of ex-smoking E-cigarette users. Nicotine Tob Res 17(2): 186-192.

- Yingst J, Foulds J, Veldheer S, Cobb CO, Yen MS, et al. (2018) Measurement of Electronic Cigarette Frequency of Use Among Smokers Participating in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Nicotine Tob Res 22(5): 699-704.

- Manrique Ruiz Tapia MA, Macías López MP, Murcia Casas DZ, Ramírez GL, Barreto KT, et al. (2022) Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index (ECDI) in a Colombian Sample. Int J Psychol Res (Medellin) 15(1): 20-29.

- Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the Reflux Symptom Index (RSI). J Voice 16(2): 274-277.

- Saúl A, Reynoso M (2009) Initial validation of the Reflux Symptom Index for clinical use. 54.

- Rosen CA, Lee AS, Osborne J, Zullo T, Murry T (2004) Development and Validation of the Voice Handicap Index-10. Laryngoscope 114(9): 1549-1556.

- Román Zubeldia J, Farías PG, Román Zubeldia J, Farías PG (2024) Adaptation and validation of the Voice Handicap Index and its abbreviated version to the Spanish of the River Plate of Argentina. J Res Innovation Health Sci 6(1): 127-147.

- Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA, Rees CJ, Pryor JC, Postma GN, et al. (2008) Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10). Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 117(12): 919-924.

- Peláez RB, Sarto B, Segurola H, Romagosa A, Puiggrós C, et al. (2012) Translation and validation of the Spanish version of the EAT-10 scale (Eating Assessment Tool-10) for the screening of dysphagia. Nutr Hosp 27(6): 2048-2054.

- Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA (2001) The validity and reliability of the Reflux Finding Score (RFS). Laryngoscope 111(8): 1313-1317.

- Proctor RN (2012) The history of the discovery of the cigarette-lung cancer link: evidentiary traditions, corporate denial, global toll. Tob Control 21(2): 87-91.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.