Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Relationship Between Viral Load And Clinical Stages in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 And Tuberculosis Co-Infected Patients at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital and Kisumu County Hospital, Kenya

*Corresponding author: Kambale Kisuba, School of Public Health and Community Development Department of Biomedical Sciences and Technology, Maseno University and Department of Microbiology, Institut Superieur des Techniques Medicales de Goma (ISTM – GOMA), DR. Congo.

Received: February 17, 2025; Published: February 25, 2025

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2025.26.003392

Abstract

Introduction: In dual tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection, each disease speeds up the progression of the other. The risk of death in TB-HIV co-infected individuals is also twice that of HIV infected individuals without TB. It is important to get a viral load test to determine the level of HIV in blood for treatment assessment. This study aimed to determine the HIV viral load levels in various clinical stages of HIV infection and clinical form of tuberculosis (pulmonary and extra-pulmonary TB).

Methodology: This research adopted a cross sectional design involving data collection from a population of patients aged 5 to 65 years’ old; tested HIV positive and co-infected with MTB. For sampling, we considered 88 – 44 from Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital (JOOTRH) and 44 others from Kisumu County Hospital (KCH). Adult participants were consented and children gave their assent despite consent from their parents. Whole blood was drawn from the 88 clients for viral load testing. Pearson Chi-square Test and Fisher’s Exact Tests were used through SPSS 20.0 for data analysis.

Results: Findings showed that most of the study participants (78.0%) with high viral load (> 10.000 copies/ml) were found in HIV stage three with pulmonary TB while 22.0% were in HIV stage four with extra-pulmonary TB. There was a statistical significance between viral load and HIV clinical stages (p = 0.004) and also a statistical significance between viral load and TB clinical form (p=0.006).

Conclusion: Overall, the results showed a positive relationship between viral load and HIV clinical stages, and also with pulmonary TB; but not with extra-pulmonary TB. These findings are useful to enhance HIV and TB co-infection management system by enabling viral load testing repeats to follow up HIV and TB medication and also by enhancing patient’s mobilization against dropping treatment, which may lead to drug resistance.

Keywords: Relationship, Tuberculosis, HIV, Viral load, Clinical Stages

Introduction

TB and HIV co-infection is when people have both HIV infection, and also either latent or active TB disease. When someone has both HIV and TB each disease speeds up the progress of the other. In addition to HIV infection speeding up the progression from latent to active TB, M. tuberculosis also accelerates the progress of HIV infection [1]. The risk of progressing from latent to active TB is estimated to be between 12 and 20 times greater in people living with HIV than among those without HIV infection [2]. From WHO and CDC, it has been clarified that Stage I of HIV infection is asymptomatic; Stage II: mild symptoms which may include minor mucocutaneous manifestations and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections; Stage III: advanced symptoms – associated with pulmonary TB – and Stage IV or AIDS: severe symptoms related to various opportunistic infections like extra-pulmonary TB, etc. [3,4].

In 2016, 374,000 people who had both TB and HIV were estimated to have died worldwide [5]. About 70% of people living with HIV are found in sub-Saharan Africa. The proportion of known HIV positive TB patients on antiretroviral therapy (ARVs) is 78% globally, and above 90% are in Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Uganda and Swaziland. The important goal of HIV treatment is to keep the viral load so low that the virus can’t be detected by a viral load test [6]. Kenya has the joint fourth-largest HIV epidemic in the world (alongside Mozambique and Uganda) in terms of the number of people living with HIV, which was 1.5 million people in 2015. Roughly 36,000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses in the same year, although this figure is steadily declining from its total of 51,000 in 2010 [7]. The HIV prevalence peaked at 10.5% in 1996, and had fallen to 5.9% by 2015 in Kenya, but co-infection HIV/TB statistics are going up [8].

Several studies have been done and are related to different aspects of HIV and TB co-infection, but none of them focused on relationship between HIV viral load with various clinical stages of HIV and TB co-infection and HAART and anti-TB treatment. For example, Lukas et al, [9] conducted a study on HIV viral load as an independent risk factor for tuberculosis in South Africa. The study showed that TB incidence was higher in patients with high HIVRNA compared to patients with lower HIV-RNA. Another previous study on HIV–TB co-infection, did not take into account the HIV viral load and TB relationship, but limited to positivity and negativity of laboratory tests. The study described 110 TB patients; among them, 99 were tested for HIV infection, of which 40 (40.4%) were positive for HIV. The proportion of HIV-positive participants among TB patients was significantly higher compared with the proportion of HIV infection, (22.3%) among smear- and/or culture-negative pulmonary TB suspects (p=0.001) [10]. A previous study found co-infections to contribute to HIV-related pathogenesis and often increase viral load in HIV-infected people [11]. Another study [12], postulated that immunocompromised individuals still have a significantly higher likelihood of infection by other pathogenic viruses (e.g., influenza virus) and experience worse symptoms compared with healthy persons. Another one described several infectious condi tions found in HIV patients, such as influenza/influenza-like illness (ILI), Lower Respiratory Tract Infections (LRTIs), Opportunistic Infections (OIs) and Tuberculosis (TB) in HIV-Infected Children [13]. In link with the above statements, much information on HIV and TB co-infection are available without taking in account simultaneously the number of viruses (viral load) related to the progress of HIV infection. Although, in order to supplement former researches, many other studies have to be done so as to determine the possible link between levels of HIV viral load and HIV clinical stages in case of HIV and TB co-infection. As such, the current study determined the HIV viral load levels in HIV infection clinical stages in HIV and TB co-infected patients in HIV and TB co-infected patients at JOOTRH and Kisumu County Hospital.

Annual statistics from Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital and Kisumu County Hospital (2021 to 2023) have shown that HIV and TB co-infection is frequent. Actual data (up to 2023) are showing that HIV and TB co-infected patients are increasing in number. It was reported 89; 92 and 109 cases respectively in 2021, 2022 and 2023 at JOOTRH and in the same order 73; 90 and 93 for Kisumu County Hospital [14]. Therefore, more studies are needed to be done in the particular area of HIV and TB co-infection for the well-being of these kind of patients and also, to prevent non-infected people. This study contributes to enhance HIV and TB co-infection management system by showing the correlation between HIV viral load with the clinical stages of HIV and TB co-infection and HART and anti-TB treatment in order to improve public health. It also provides new knowledge on the body’s response to HAART (ARVs) and anti-TB treatment.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

This study was conducted at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital and Kisumu County Hospital in Kenya. These two health facilities are located in the western part of Kenya, within Kisumu County.

Study Design

This research followed a cross sectional design based on the type of study population, period and methods of data collection. A cross-sectional study involves looking at data from a population at one specific point in time. The participants in this type of study are selected based on particular variables of interest. Cross-sectional studies are often used in developmental psychology, but this method is also utilized in many other areas including social science, education and public health researches [15].

Study Population

The target population is constituted of patients tested and found to be HIV positive and co-infected with MTB. The participants were between 5 to 65 years old. Under five years old children and old persons such as above 65 years old are known to have weaker immune system because of immaturity of immune organs for children and thymus atrophy for elder people. This weak immune system may be in fever of virus replication and lead to a high viral load. It has been clarified that as age advances, the immune system undergoes profound remodeling and decline, with major impact on health and survival [16,17]. This immune senescence predisposes older adults to a higher risk of acute viral and bacterial infections. Moreover, the mortality rates of these infections are three times higher among elderly patients compared with younger adult patients [18].

Procedure For HIV and AIDS Clinical Staging

A clinician helped with staging all the patients using the World Health Organization [3]. procedure as follows: All patients with either asymptomatic or associated with acute retroviral syndrome are classified in primary HIV infection; Asymptomatic patients with a CD4+ T cell count (also known as CD4 count) greater than 500 per microliter (μl or cubic mm) of blood may include generalized lymph node enlargement are in stage I; Stage II is constituted by patients with mild symptoms which may include minor mucocutaneous manifestations and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections. A CD4 count of less than 500/μl; Stage III includes patients with advanced symptoms which may consist of unexplained chronic diarrhea for longer than a month, severe bacterial infections including tuberculosis of the lung, and a CD4 count of less than 350/μl; Patients with severe symptoms which include toxoplasmosis of the brain, extra-pulmonary TB candidiasis of the esophagus, trachea, bronchi or lungs and Kaposi’s sarcoma and a CD4 count of less than 200/μl are classified in stage IV or AIDS [3].

Sample Size Determination

With 88 HIV and TB co-infected patients, the detectable effect size of 0.28 (a two tailed – test) was expected with the 80% power and α (false – positive rate) of 0.05. The detectable effect viral load was assumed on prevalence of ARN copies. In total, for the two hospitals, the study population was 92 patients. Three patients refused to provide blood sample while one patient died before giving blood for viral load. From the 88 remaining patients, a number of 44 of these patients were considered for each of the two health facilities [19].

Eligibility Criteria of Study Participants

The participants tested HIV-positive and MTB (M. tuberculosis) positive; with 5 to 65 years old were selected. But those tested HIV positive only and negative for MTB or positive for MTB and HIV negative and also, those who were vaccinated the same week of sample collection. we’re not part of the study.

Laboratory Analysis

Sample Collection and Processing

In order to protect the investigators (researcher, clinician – Doctor or Nurse, lab staff) from potential infections from biohazards, proper use of sterile gloves, disinfectant, laboratory coat and safety bio-cabinet was a must during the whole process of sample collection and processing. Peripheral venous blood samples (4ml) were collected from each patient and be put in vacutainer tubes, at room temperature, for centrifugation (2400 revolutions per minute for 10minutes) then, 2.5ml of plasma were collected and be put in well labeled tubes for viral load testing.

Viral Load Testing

Specimen Handling and Storage

Whole blood specimens were kept at 19°C for up to 24 hours before testing. The whole blood was centrifuged at 2400 RPM at 10 minutes at room temperature to extract and separate the plasma. It is recommended that plasma be stored in 1.1 - 1.2ml aliquots in sterile, 2.0 mL polypropylene screw-cap tubes. Plasma specimens were stored at room temperature (25°C) for up to 1 day, or at 2°C to 8°C for 6 days, or frozen at -20°C to -80°C for up to 6 weeks. Clinicians handling and storing specimens followed appropriate standard operating procedures for the process.

Assay Protocol Summary

Thaw assay controls, calibrators, IC (Internal Control), amplification reagents and samples at 15-30°C. Invert gently Sample Preparation bottles to ensure a homogeneous solution without generating any bubbles. Add 500 μL of IC to each bottle of lyses Buffer. Mix by gently. Vortex specimen and centrifuge at 2,000g for 5 minutes. Place the low and high positive controls, and the patient specimens into the Abbott m2000sp sample rack. Place the 5 mL Reaction Vessels into the m2000sp 1 mL subsystem carrier. Load the Abbott m Sample Preparation System reagents and the Abbott 96 Deep-Well Plate on the Abbott m2000sp worktable. Select the appropriate application file for sample extraction. Load the amplification reagents and the master mix vial after sample preparation is completed. Remove and discard the amplification vial caps. Switch on and initialize the instrument. Seal the Abbott 96-Well Optical Reaction Plate after the instrument has completed addition of samples and master mix. Export completed PCR plate results to a CD. Place the Abbott 96-Well Optical Reaction Plate in the Abbott m2000rt instrument. Import m2000sp test order via CD. Place the Abbott 96-Well Optical Reaction Plate in a sealable plastic bag and dispose. Calculate the concentration of viral HIV-1 RNA and report in Copies/mL or in Log [Copies/mL] (97/656).

Validity and Reliability

HIV viral load determines how infectious bodily fluids are. Levels are highest in someone who is recently infected (up to 40 million copies in a milliliter of blood). By comparison, someone on treatment with an undetectable viral load has less than 50 copies/ mL and a viral load of 10,000 copies /ml is known to be lower wile > 10,000 copies/ml is higher.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

After laboratory works, data were analyzed using SPSS statistics 20.0. The Fisher’s Exact Test was used to determine HIV viral load levels in various clinical stages of HIV infection, Pearson Chisquare Test used to associate the level of viral load with clinical forms of TB (pulmonary and extra pulmonary TB).

Ethical Considerations of the Study

In order to keep confidentiality, each of the study participants was given a unique code for identification. They were assured that the data were to be used for research purposes only. The participants received adequate explanation about the study in simple understandable language for informed consent for adults. Children provided assent besides obtaining consent from their parents or guardians. The participants were informed of their rights to withdraw from the study at any time. The study was officially approved. The first ethical approval was obtained from the Maseno University Ethical Review Committee (MUERC), while the second was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital, Kisumu.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

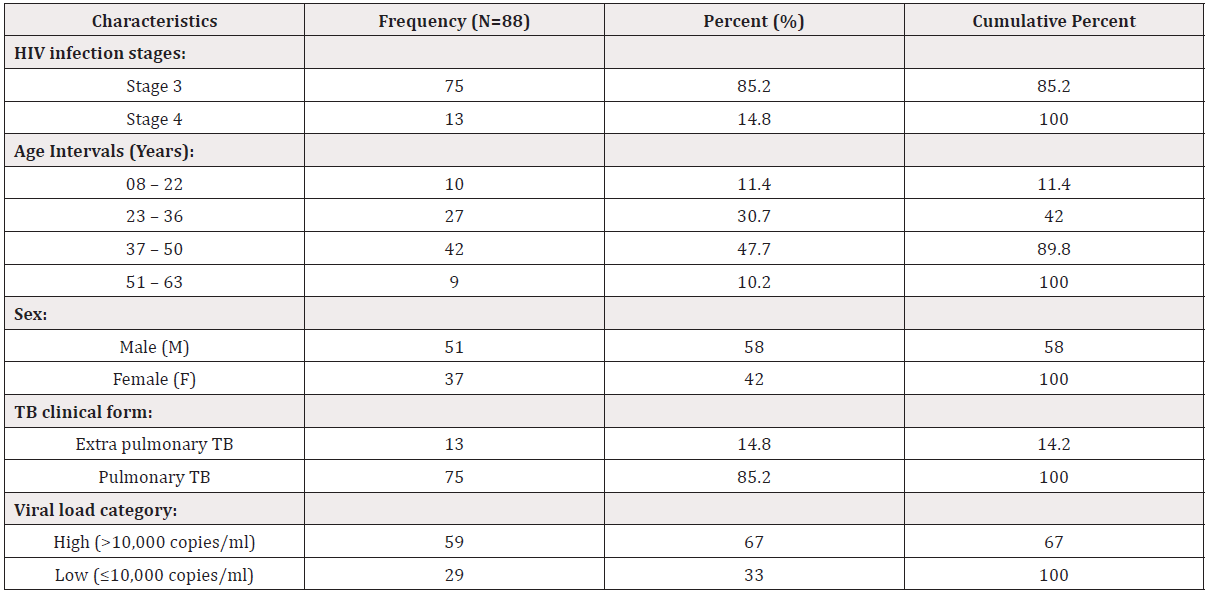

The demographic characteristics of the study participants have shown that 10 (11.4%) out of 88 HIV and TB co-infected patients were aged 08 to 22 years old, 27 (30.7%) were aged 23 to 36, and most of the participants 42 (47.7%) were aged 37 to 50 years old while only 9 (10.2%) were in the interval of age 51 to 63 years old. According to gender, most of the patients were males, 51 (58.0%) while females were 37 (42.0%). Most of the participants, 75 (85.2%) were HIV infection stage three (3) and had pulmonary TB while 13 (14.8%) of them were in stage four (4) with extra pulmonary TB. A large number of these patients 59 (67%) had a higher viral load (> 10,000 copies/ml) while 29 (33.0) of them had a lower viral load (≤ 10,000 copies/ml) (Table 1).

Proportions for various parameters (HIV infection stage, age and sex of the participants, TB clinical form and viral load category - high [> 10,000 copies/ml] or low [≤ 10,000 copies/ml] of the participants) were calculated relate to their frequencies expressed in % with N= study sample size. The cumulative percent is the total of frequencies for each clinical characteristic.

Relationship Between Viral Load Levels and HIV Clinical Stages

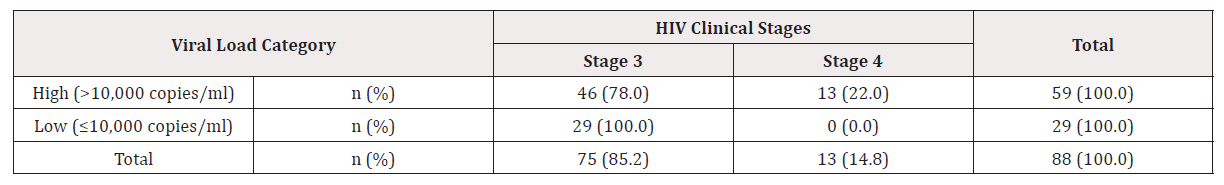

Majority of the study participants 46 (78.0%) out of 59 (100.0%) with high viral load were found to be in stage three of HIV infection while 29 (100.0%) of those with low viral load – all of them –were in clinical stage three. On the other hand, all the patients13 (22.0%) found to be in HIV infection stage four had a higher viral load. There was a statistical significance between the viral load and the HIV clinical stages (Fishers Exact test, p = 0.004) (Table 2).

n (%): proportion of patients with high or low viral load related to the observed parameters (HIV stages and viral load) in Table 3. HIV=Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection cases; Stage 3= HIV clinical stage, representing 75 cases (85.2%) of study participants; Stage 4= HIV clinical stage, representing 13 cases (14.8%) of study participants = 88 participants.

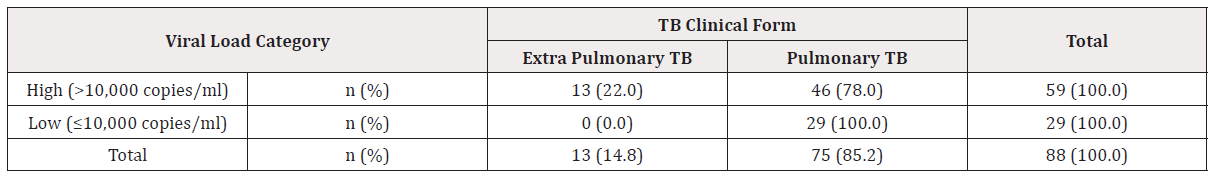

Relationship Between Viral Load Levels and TB Clinical Form

Two clinical forms of tuberculosis are known, Pulmonary and Extra-pulmonary TB. For this study, it was found that majority of the participants 46 (78.0%) out of 59 (100.0%) having high viral load (> 10,000 copies/ml) were developing pulmonary TB, while 13 (22.0%) with high viral load had extra-pulmonary TB. The same table 4.4 is showing 29 (100.0%) patients with pulmonary TB out of 29 (100.0%) having low viral load (≤ 10,000 copies/ml). No any case of extra-pulmonary TB 0 (0.0%) appeared with low viral load. This has shown a statistical significance between viral load and TB clinical form (Pearson Chi-Square 7.497; df 1; p= 0.006) (Table 3).

n (%): proportion of patients with high or low viral load related to the observed parameters (TB clinical forms and viral load). Pulmonary TB for 75 cases (85.2%) of study participants; extra-pulmonary TB for 13 cases (14.8%) of study participants = 88 patients.

Discussion

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

This study done on HIV and TB co-infected patients, demographic clinical characteristics have shown respectively that most of the participants, 47.7% were aged 37 to 50 years old, 30.7% were 23 to 36 years old and 11.4% were between 08 to 22 years old, while only 10.2% were in the interval of age 51 to 63 years old. According to gender, males were predominant, 58.0% while female were 42.0%. The current study found out that 85.2% of participants were HIV infection stage three (3) and had pulmonary TB while 14.8% of them were in stage four (4) with extra pulmonary TB. Most of these patients, 67% had a higher viral load (>10,000 copies/ml) while 33.0% of them had a lower viral load (≤10,000 copies/ml). These findings are consistent with a study done by Peter et al, [20] describing that among 266 persons who were currently taking ART, they observed significant differences in the proportion of detectable viremia across age groups: 22·3% among persons aged 30–64 years compared with 46·5% among persons aged 15–29 years (p<0·0001). A similar study was carried out by Maria et al, [21], in which HIV–MTB co-infection was more common in adults with an average age of 33–45 years. A previous study done by Peter et al, [20], showed in multivariate analysis for the subsample of patients on ART, detectable viremia was independently associated with younger age and sub optimal adherence to ART. It was also shown in another study conducted in South Africa that majority of HIV positive patients co-infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis were in interval 28–40 years of age [9]. For another similar study undertook by Jialun et al, [22], males were predominant, 74% among the study participants. Agneta et al, [23] found out the same result in a study undertook in Kenya, on study participants aged 15–64 years who had heard of tuberculosis, of whom 2.0% reported having prior tuberculosis. This is in contrast with a study in South Africa for which 69.3% of study participants were females [9]. The difference in gender may be due to the various sample size for the different studies and may not significantly affect the outcome for this particular study.

Relationship Between Viral Load Levels and HIV Clinical Stages

According to the findings of this study, majority of the participants with high viral load were found to be in stage three of HIV infection while those with low viral load – all of them – were in clinical stage three. On the other hand, all the patients found to be in HIV infection stage four had a higher viral load. There was a statistical significance between the viral load and the HIV clinical stages. These findings are consistent with a study conducted in India, where HIV-1 viral load was reported to be high in patients in HIV stage four [24]. A similar earlier study conducted by John et al, [25], showed that HIV viral load was higher in the TB group, HIV stage three followed by HIV stage four. Similarly, another study [26], found out that patients who were initiated to treatment with a viral load baseline above 10,000 copies/mL experienced an increase in viral rebound and also an increase in immune deterioration from stage 2 to stage 3 or stage 4 and a reduced viral suppression developing TB in the two late stages of HIV infection. This corroboration between the previous and the findings of the current study may be due to the similarities in the use of WHO HIV staging, and potentially the same laboratory equipment (laboratory methods) for testing.

It has been explained by Avert et al, [27] that the asymptomatic phase lasts for around ten years on average. The same study [27], showed that the length of the asymptomatic phase depends on how quickly the CD4 cell count declines. If a person has a very high viral load (above 100,000 copies/ml), they will lose CD4 cells more quickly. HIV viral load is typically undetectable below levels of 40 to 75 copies/mL. The exact number depends on the lab that analyzes the tests. So as to validate the results of the current study, basic principles were taken into account as postulated by Puren et al, [28] that different test methods often give different results for the same patient sample. To be comparable the same test method (Target amplification, probe specific amplification, or signal amplification) should be used each time a patient specimen is run. Ideally patient testing should be conducted at the same medical laboratory, using the same viral load test and analyzer. Time of day, fatigue, and stress can also affect viral load values. Recent immunizations or infections can affect the viral load test. Testing should be postponed for at least four weeks after an immunization or infection. Another postulate supporting findings of the current study is from Roger et al, [29] who found viral load in blood and in other body fluids is usually very similar – if HIV in blood is undetectable, it’s likely to be undetectable elsewhere. Occasionally people have undetectable HIV in blood and have low levels of HIV in other body fluids, but very rarely at infectious levels. Reason why, in the current study, plasma from blood was used for viral load testing.

In contrast with findings of the current study, Richard et al, [30], found in their study the median viral load dropping from 205,862 in week 1 to 119,000 in week 6. In the 1st week after diagnosis, viral loads in early infections are generally several times higher than those in later stages at diagnosis. By the 3rd week, however, most are lower than those in stage 3 and stage four. Peter et al, [20] are not supporting findings of the current study by saying that the individual level, there is clear evidence that Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) transmission can be substantially reduced by lowering viral load. However, there are few data describing population-level HIV viremias especially in high-burden settings with substantial under-diagnosis of HIV infection.

In comparison with Peter et al, [20], it had been shown by other researchers like Dye et al, [31] that HIV clinical staging, adherence to treatment and good drug prescription are the most important procedures to decrease viral load and reduce the HIV transmission in any population. This may not be same for the current study due to the fact that in the previous study, the study participants were HIV patients from stage one to four, while in the current study; the staging was based on TB co-infection, which is found in stage 3 and 4 of HIV infection. Variability in study participants and sample size may be another reason of difference.

Relationship between Viral Load Levels and TB Clinical Form

Two clinical forms of tuberculosis are known, Pulmonary and Extra-pulmonary TB. For this study, it was found that 78.0% of the participants having high viral load (>10,000 copies/ml) had pulmonary TB, while 22.0% with high viral load had extra-pulmonary TB. In the current study, it was also indicated that all the patients with low viral load (≤10,000 copies/ml) were found to have pulmonary TB. No any case of extra-pulmonary TB appeared in patients who had low viral load. There was a statistical significance between viral load and TB clinical form. These findings are consistent with a study in South Africa [25], from which an episode of TB was associated with a small – adjusted increase in HIV load at the end of the study. According to the South African study, prevention of TB is important for the reduction of HIV-related morbidity and mortality because good prevention leads to decrease in HIV viral load [25]. Another study [32], found similar findings in which most common clinical form of TB was the isolated pulmonary form, occurring in 37% of the cases. However, the extra-pulmonary (36%) and disseminated (22%) forms occurred at a higher frequency than has been observed among HIV seronegative patients [32]. The findings of the current study are consistent with another study [9] in South Africa in which in accordance with WHO clinical staging, most of the participants co-infected with HIV and TB, 22.2% in the study, were found in stage three versus 15.6% in stage four. Similarly, Agneta et al, [23] found out that prevalence of laboratory-confirmed HIV infections in persons reporting prior tuberculosis was 33.2% with predominant pulmonary TB. While for the current study also the majority of patients with high viral load were found in stage three of HIV infection. The same study conducted by Lukas et al, [9] clarified that the rest of clients were classified as stage one and two and were not co-infected with TB. This did not much with the current study in which stage one and stage two of HIV infection was not considered. In a previous study [25], pulmonary TB were found in 73.2% and extra-pulmonary TB in 26.8% the study participants; while Oyomopito et al, [33] reported that 85% of cases of TB were restricted to the lungs and the remaining 15% were extra- pulmonary. These results are similar to those from the current study, showing 85.2% of pulmonary TB and 14.8% of extra-pulmonary TB among HIV and TB co-infected patients at JOOTRH and Kisumu County Hospital. Same way, the findings of a previous study [31], from a modeling showed that the burden of HIV among newly-diagnosed TB patients varied considerably; whereas 47% of newly-diagnosed TB patients tested HIV-positive in Tanzania, 70% in Botswana and Zambia, 78% in Zimbabwe and 84% in Swatini (Swaziland) did so. A previous study done in Uganda by Michael et al, [34] had shown that quarter of Ugandan HIV-positive patients with active Tuberculosis (TB) had a viral load below 10,000 copies/ ml. Furthermore, the investigators found that viral load increased in a significant proportion of patients whose viral load was below 1000 copies/ml after they started treatment with anti-TB drugs. These findings are unexpected as TB is usually associated with an increase in HIV viral load as it for the current study done at JOOTRH and KCH, Kenya. The same was described from another study done by Srikantiah et al, [35] which found that 49 patients had a baseline viral load below 10,000 copies/ml, with twelve of these individuals having a viral load below 1000 copies/ml. Earlier investigators could find no obvious patient characteristics associated with a lower viral load during active TB infection as it was found in the current study [35]. One may tend to think that these various studies were done in same conditions with the current.

According to the statement below, pulmonary TB is more likely to be found in HIV patients than extra-pulmonary TB. In contrast, Oyomopito et al, [33] postulated that this distribution has changed among HIV and TB co-infected patients. This statement may be associated with the difference in sample size and study area for two studies. The current study was done in two hospitals in Kenya (one country) and involved 88 patients while Dye et al [31] did they study in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Zambia and Swaziland with a sample size of 36,522 patients. Morbidity from tuberculosis and HIV remain major health challenges in Kenya and other countries. Tuberculosis is an important entry point for HIV diagnosis and treatment of the two diseases.

Conclusion

For the findings established in this study, it has been shown clearly that: HIV clinical stages were significantly associated with high viral load. The majority of the study participants was in HIV infection stage three and had high viral load. All of those patients found in the late stage – stage four – had also a higher viral load. For TB clinical form (Pulmonary and extra-pulmonary TB), there was a positive relationship between HIV viral load and pulmonary TB but, a negative relationship was found between viral load level and extra- pulmonary TB, may be due to the number of cases being fewer in this particular category of patients with extra-pulmonary TB. In fact, the two group of clients had a higher viral load. For enhancing HIV and TB management, HIV viral load testing repeats should be done for a successful medication follow up in order to maintain a very low – undetectable – viral load and control opportunistic infections (TB being one of them). This may also guide clinicians to change the regimen of treatment for HIV and TB patients.

Limitations of the Study

It has been known that immune system maturity is related to age. Young and old people are naturally immune deficient. Therefore, only patients aged 5 to 65 years old were taken in account, as defined in inclusion criteria.

Due to the limitations, patients under 5 years and those of the age beyond 65 years old were not be considered. Which affected the study sample size, by reducing the study population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kambale Kisuba; methodology, Kambale Kisuba, Guyah Bernard and Collins Ouma; resources, Kambale Kisuba, Guyah Bernard, Collins Ouma; writing—original draft preparation, Kambale Kisuba, Guyah Bernard and Collins Ouma; writing—review and editing, Kambale Kisuba, Guyah Bernard, Collins Ouma.; Final editing, All authors; visualization, Kambale Kisuba; supervision, Guyah Bernard and Collins Ouma; project administration, Kambale Kisuba. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the HIV – R Lab staff, KEMRI/CDC Kisian for allowing us to run our assay in their laboratory.

We are grateful to the TB clinic staff of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital and Kisumu County Hospital for helping me during sample collection. Thanks to all HIV and TB co-infected patients who gave their blood samples for this project.

References

- Solomon A, Thandisizwe M, Ribka F,Tadesse A (2016) Outcomes of TB treatment in HIV co-infected TB patients in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional analytic study, BMC Infectious Diseases, volume 16, Article number: 640.

- Luetkemeyer A (2018) Tuberculosis and HIV. HIV InSite.

- WHO (2007) case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children. (PDF) Geneva: pp 6-16.

- Quinn TC, M J Wawer, N Sewankambo, D Serwadda, C Li, et al. (2000) Viral load and heterosexual transmission of HIV type 1 Rakai Project Study Group. New England Journal of Medicine342: 921-929.

- WHO Geneva (2017) Global Tuberculosis Control 2017.

- Granich R, Williams B, Montaner J (2013) Fifteen million people on antiretroviral treatment by 2015: treatment as prevention. Curr Opin HIV AIDS; 8:41-49.

- UNAIDS (2016) Fact sheet 2015.

- Kenya National AIDS Control Council (2014) Kenya AIDS Strategic Framework 2014/2015 – 2018/2019

- Lukas F, Andrew A, Andrew B, Matthew F, Hans P, et al. (2017) HIV viral load as an independent risk factor for tuberculosis in South Africa: collaborative analysis of cohort studies, J Int AIDS Soc, 20(1): 21327.

- Mulugeta B, Gunnar B, Fekadu A (2017) Prevalence of tuberculosis, HIV, and TB-HIV co-infection among pulmonary tuberculosis suspects in a predominantly pastoralist area, northeast Ethiopia. 18(1): 27949.

- Kayvon M, Sten V (2010) Effect of treating co-infections on HIV-1 viral load: a systematic review Lancet Infect Dis 10(7): 455-463.

- Thitilertdecha P, Khowawisetsut L, Ammaranond P, Poungpairoj P, Tantithavorn V, et al. (2017) Impact of Vaccination on Distribution of T Cell Subsets in Antiretroviral-Treated HIV-Infected Children. Dis Markers: 5729639.

- Visal M, Suthat C, Jarurnsook A, Sirirat L, Sumonmal U, et al. (2018) The Effect of Detectable HIV Viral Load among HIV-Infected Children during Antiretroviral Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children (Basel) 5(1): 6.

- JOOTRH and KCH (2021 to 2023) Annual reports, HIV and TB co-infection.

- Kendra C, Steven G (2019) Cross-Sectional Research Method, Advantages and Challenges.

- Weiskopf D, Weinberger B, Grubeck Loebenstein B (2009) The aging of the immune system. Transplant Int 22(11): 1041-1050.

- Jiang N, He J, Weinstein J, Penland L, Katharina S, et al. (2013) Lineage structure of the human antibody repertoire in response to influenza vaccination. Sci. Transl Med 5(171): 171ra19.

- Katharina S, Georg H, Andrew M (2015) Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proc Biol Sci 282(1821): 20143085.

- Bumc (2020) Molecular Analysis and simple HIV testing.

- Peter C, Andrea K, Timothy K, Kenneth S, Anthony W, et al. (2016) Detectable HIV Viral Load in Kenya: Data from a Population-Based Survey. PLos One 11(5): e0154318.

- Maria M, Arun C, Alexandria B, Sowmya P, Naveen P, et al. (2015) HIV-Associated TB Syndemic: A Growing Clinical Challenge Worldwide, Front Public Health 3: 281.

- Jialun Z, Thira S, Sasisopin K, Yi Ming C, Ning H, et al. (2010) Trends in CD4 counts in HIV-infected patients with HIV viral load monitoring while on combination antiretroviral treatment: results from The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database. BMC Infectious Diseases 10: 361.

- Agneta M, Anthony G, Andrea K, Abraham K, Herman W, et al. (2016) Tuberculosis and HIV at the National Level in Kenya: Results From the Second Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 66(Suppl 1): S106-115.

- Shah L, Price A, Blondeau C, Hilditch L (2006) Correlation of CD4 count, CD4% and HIV viral load with clinical manifestations of HIV in infected Indian children, the paediatric and perinatal HIV clinic in a tertiary care hospital over a period of 4 years, from January 1999 to December 2003, Pediatric Tropical Annals.

- John D, Alison G, Katherine F, Lynn M, Victoria M, et al. (2004) Does Tuberculosis Increase HIV Load, The Journal of Infectious Diseases 190(9): 1677-1684.

- Claris S, Delson C, (2019) A superiority of viral load over CD4 cell count when predicting mortality in HIV patients on therapy. BMC Infectious Diseases 19(1): 169.

- Avert T, Benedetti A, Harries A (2018) Global information and education on HIV and AIDS, The science of HIV and AIDS – overview, nov.ppb. UK, charity: 1074849.

- Puren A, Gerlach L, Weigl H, Kelso M, Domingo J, et al. (2010) Laboratory Operations, Specimen Processing, and Handling for Viral Load Testing and Surveillance. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 201(Suppl 1): 27-36.

- Roger P, and Nam A (2019) Undetectable viral load and transmission – information for people with HIV, NAM Charity, England & Wales, number: 2707596; 1011220.

- Richard S, Laurie L (2018) Viral Loads Within 6 Weeks After Diagnosis of HIV Infection in Early and Later Stages: Observational Study Using National Surveillance Data, JMIR Public Health 4(4): e10770.

- Dye C, Williams B (2019) Tuberculosis decline in populations affected by HIV: a retrospective study of 12 countries in WHO African Region. Bull World Health Organ 97(6): 405-414,

- Giselle K, Tuba K (2005) Clinical forms and outcome of tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients in a tertiary hospital in São Paulo – Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis 9(6): 464-478.

- Oyomopito R, Lee M, Phanuphak P, Lim P, Ditangco R, et al. (2010) Measures of site resourcing predict virologic suppression, immunologic response and HIV disease progression following highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database (TAHOD). HIV Med 11 (8): 519-529.

- Michael Carter, French M, Chanda D, Sowmya P (2009) TB doesn't always increase HIV viral load, Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, Syndr 49: 458-460.

- Srikantiah P, Joseph W, Teri L, Maria W, Harriet K, et al. (2008) Unexpected low-level viremia among HIV-infected Ugandans adults with untreated active tuberculosis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 49(4): 458-460.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.