Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Diagnostic Significance of Hematological, Biochemical, and Immune Markers in Thalassemia and Sickle Cell Disease

*Corresponding author: Md Samiul Bashir, Department of Laboratory Medicine Institute of Health Technology, Kurigram, Bangladesh mtsamiulbashir@gmail.com

Received: May 16, 2025; Published: May 21, 2025

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2025.27.003525

Abstract

Background: Thalassemia and sickle cell disease (SCD) are prevalent hemoglobinopathies in Bangladesh, requiring accurate diagnostic markers for differentiation and management. This study evaluated the diagnostic significance of hematological, biochemical, and immune markers in these disorders.

Purpose of the Study: This study aimed to identify and validate hematological, biochemical, and immune markers for accurate differentiation and improved management of thalassemia and sickle cell disease in resource-limited settings.

Methods: A cross-sectional study of 230 participants (100 thalassemia, 100 SCD, 30 controls) was conducted at a tertiary care hospital. Hematological (MCV, RDW, reticulocytes), biochemical (ferritin, LDH, haptoglobin), and immune markers (IL-6, TNF-α, oxidative stress) were analyzed using HPLC, ELISA, and automated assays. Statistical analysis included ROC curves and correlation tests.

Results: Thalassemia patients exhibited microcytic anemia (MCV 65.3 fL, hemoglobin 7.2 g/dL) with elevated ferritin (1850 ng/ mL), while SCD patients had normocytic anemia (MCV 82.1 fL, hemoglobin 8.1 g/dL) with higher reticulocytosis (12.3%) and inflammation (IL-6: 25.1 pg/mL). MCV ≤72 fL distinguished thalassemia (AUC 0.92, 94% specificity), and IL-6 ≥18 pg/mL identified SCD-related inflammation (AUC 0.79). Oxidative stress was more severe in SCD (MDA 8.2 nmol/mL vs. 5.8 nmol/mL in thalassemia).

Conclusion: MCV, ferritin, and IL-6 are robust diagnostic markers for thalassemia and SCD in resource-limited settings. These findings support tailored screening algorithms and therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: Thalassemia, Sickle Cell Disease, Hemoglobinopathies, Diagnostic Markers, Bangladesh

Introduction

Thalassemia and sickle cell disease (SCD) represent two of the most common inherited hemoglobin disorders globally, presenting major public health challenges particularly in tropical and subtropical regions including Bangladesh [1]. These chronic blood disorders result from genetic defects affecting hemoglobin molecules, leading to severe anemia, progressive organ damage, and significant morbidity and mortality if not properly managed [2].

Thalassemia syndromes occur due to mutations that reduce or completely prevent the synthesis of α- or β-globin chains, creating an imbalance in hemoglobin tetramer formation. This imbalance leads to ineffective erythropoiesis, chronic hemolytic anemia, and iron overload, even in the absence of blood transfusions [3]. In Bangladesh, β-thalassemia is particularly prevalent, with carrier rates estimated at 4-8% in some regions, making it one of the countries most affected by this disorder in South Asia [4].

Sickle cell disease, in contrast, results from a specific point mutation in the β-globin gene that produces hemoglobin S (HbS). This abnormal hemoglobin polymerizes under low oxygen conditions, causing red blood cells to assume a characteristic sickle shape [5]. These sickled cells are rigid and adhesive, leading to vaso-occlusive crises, chronic hemolysis, and progressive damage to multiple organ systems [6]. While traditionally considered less common in Bangladesh than thalassemia, recent studies suggest sickle cell trait prevalence may reach 5-7% in certain populations, particularly in the tribal communities of the Chittagong Hill Tracts [7].

The clinical manifestations of these disorders often overlap significantly, with both presenting with chronic anemia, jaundice, growth retardation in children, and progressive organ dysfunction [7]. This overlap creates diagnostic challenges, particularly in resource- limited settings where advanced testing may not be readily available. In Bangladesh, where healthcare resources are often stretched thin, the development of accurate yet cost-effective diagnostic algorithms are particularly crucial [8].

Diagnostic approaches to these hemoglobinopathies have evolved significantly in recent years. Traditional methods including complete blood count analysis, peripheral blood smear examination, and hemoglobin electrophoresis remain fundamental tools [9]. However, newer techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), molecular genetic testing, and advanced biomarker analysis have greatly enhanced diagnostic precision [10]. These developments are particularly relevant for Bangladesh, where the high prevalence of both conditions necessitates robust screening programs and accurate diagnostic protocols [11].

The hematological profiles of these disorders show characteristic differences that aid in differentiation. Thalassemia typically presents with microcytic, hypochromic anemia with target cells and nucleated red blood cells on peripheral smear, while SCD shows normocytic anemia with sickled cells and features of hypersplenism [12]. Biochemical markers including iron studies, lactate dehydrogenase, and bilirubin levels provide additional diagnostic and prognostic information. Furthermore, emerging research highlights the importance of inflammatory and immune markers in understanding disease progression and complications in both conditions [13].

In Bangladesh, where consanguineous marriages remain relatively common in some communities, the genetic burden of hemoglobinopathies is particularly high. This has led to increased focus on carrier screening programs and prenatal diagnosis initiatives, though significant challenges remain in implementing these services nationwide [14]. The development of point-of-care testing methods and simplified diagnostic algorithms could greatly improve case detection and management in primary healthcare settings across the country.

Aim of the study to comprehensively review the diagnostic significance of hematological, biochemical, and immune markers in thalassemia and sickle cell disease, with particular attention to their application in resource-limited settings like Bangladesh.

Methods and Materials

Study Design

This cross-sectional analytical study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital in Bangladesh from January 2022 to December 2024. The study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic significance of hematological, biochemical, and immune markers in differentiating thalassemia and sickle cell disease (SCD) among Bangladeshi patients.

Study Population

The study enrolled a total of 230 participants through consecutive sampling. The study population comprised 100 confirmed thalassemia patients (including 50 cases of β-thalassemia major, 30 cases of β-thalassemia intermedia, and 20 cases of HbE/β-thalassemia), 100 SCD patients (including 80 cases of HbSS and 20 cases of HbS/β-thalassemia), and 30 age- and sex-matched healthy controls who served as the reference group. The inclusion criteria required participants to be diagnosed cases of thalassemia or SCD confirmed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and genetic testing, aged between 5-40 years, and willing to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included recent blood transfusion (within 3 months), co-existing hematological malignancies, active infections or inflammatory conditions, and pregnancy.

Sample Collection and Processing

Venous blood samples (10 mL) were collected from each participant following standard phlebotomy procedures. The samples were distributed as follows: 3 mL in EDTA tubes for complete blood count and HPLC analysis, 5 mL in plain tubes for biochemical analysis, and 2 mL in sodium citrate tubes for coagulation studies. All samples were processed within 2 hours of collection at the hospital’s central laboratory to ensure sample integrity and minimize pre-analytical errors.

Laboratory Methods

Hematological Analysis

Complete blood count (CBC) was performed using the Sysmex XN-1000 automated hematology analyzer, measuring hemoglobin concentration, red blood cell count, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), red cell distribution width (RDW), and reticulocyte count. Peripheral blood smears were prepared and stained with Leishman stain, then evaluated independently by two hematologists for characteristic morphological features. Hemoglobin analysis was conducted using HPLC (Bio-Rad Variant II system) with confirmation by capillary electrophoresis (Sebia Capillarys 2) [14].

Biochemical Analysis

Iron studies included serum ferritin measurement by chemiluminescence immunoassay, serum iron and total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) by colorimetric method, with transferrin saturation calculated accordingly. Hemolysis markers were assessed through lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) using UV kinetic method, bilirubin by diazo method, and haptoglobin by immunoturbidimetric assay. Liver and renal function tests were performed using an automated analyzer (Beckman Coulter AU680) [15].

Immunological Markers: Inflammatory markers including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) were measured by immunoturbidimetry, while interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Oxidative stress was evaluated through malondialdehyde (MDA) levels using Thio barbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) method and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) by colorimetric assay [16].

Statistical Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data. Group comparisons were performed using ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test. Diagnostic accuracy was assessed through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Associations between markers were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants and from parents or legal guardians of minors. Confidentiality was maintained through anonymized data coding, and participants with abnormal findings were appropriately referred for clinical management.

Quality Control

Rigorous quality control measures were implemented throughout the study. Internal quality control was performed daily using commercial controls. The laboratory participated in the external quality assurance program of the Bangladesh Medical Research Council. To ensure consistency, 10% of samples were randomly selected for re-testing. Inter-observer agreement for peripheral smear analysis was maintained at an excellent level (κ >0.85). These measures ensured the reliability and reproducibility of the laboratory findings.

Results

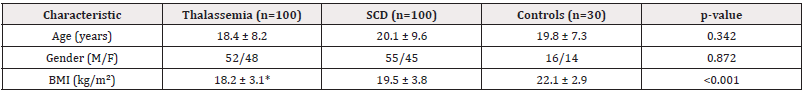

The study groups were well-matched for age and gender distribution (p>0.05). Thalassemia patients had significantly lower bmi compared to both scd patients and controls (18.2 vs 19.5 vs 22.1 kg/m², p<0.001), reflecting the nutritional impact of chronic disease. The mean age was comparable across groups (18.4-20.1 years), with a balanced gender ratio (Table 1).

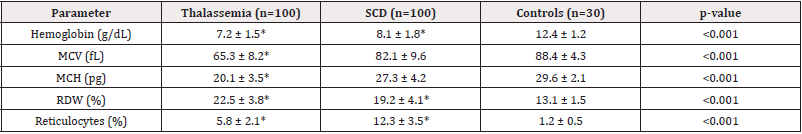

Thalassemia patients showed significantly lower hemoglobin levels compared to SCD patients (7.2 vs 8.1 g/dL, p<0.001). Microcytosis (MCV 65.3 fL) and hypochromia (MCH 20.1 pg) were characteristic of thalassemia, while SCD patients had higher MCV and MCH values. Both groups exhibited elevated RDW and reticulocyte counts compared to controls, with SCD patients showing more pronounced reticulocytosis (12.3% vs 5.8%, p<0.001) (Table 2).

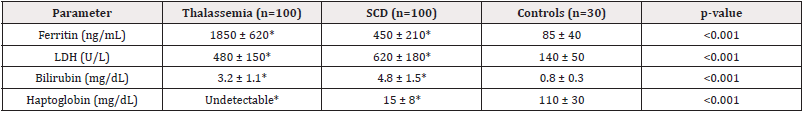

Thalassemia patients had significantly higher ferritin levels (1850 ng/mL) due to transfusion-related iron overload, while SCD patients showed moderate elevation (450 ng/mL). Hemolysis markers (LDH, bilirubin) were elevated in both groups, but more markedly in SCD (LDH 620 U/L vs 480 U/L in thalassemia, p<0.001). Haptoglobin was undetectable in thalassemia and significantly reduced in SCD compared to controls (Table3).

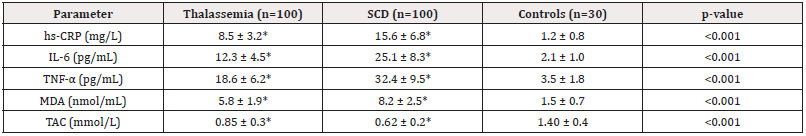

SCD patients demonstrated significantly higher inflammatory markers compared to thalassemia, with IL-6 (25.1 vs 12.3 pg/ mL) and TNF-α (32.4 vs 18.6 pg/mL) being particularly elevated (p<0.001). Oxidative stress was more pronounced in SCD, evidenced by higher MDA (8.2 nmol/mL) and lower total antioxidant capacity (TAC 0.62 mmol/L) compared to thalassemia (Table 4).

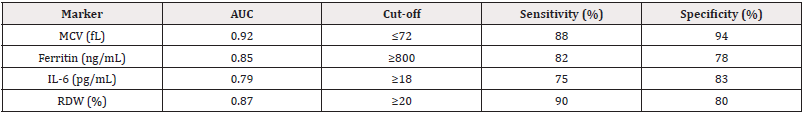

MCV demonstrated the best diagnostic performance (AUC 0.92) with 88% sensitivity and 94% specificity at a cut-off of ≤72 fL for thalassemia. Ferritin ≥800 ng/mL showed good discrimination for iron overload in thalassemia. RDW ≥20% was highly sensitive (90%) for both disorders, while IL-6 ≥18 pg/mL better identified SCD-related inflammation (Table 5).

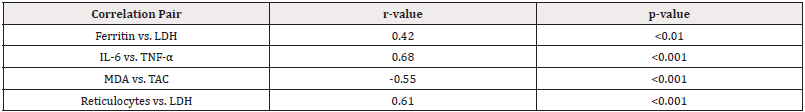

Strong positive correlations were observed between inflammatory markers (IL-6 and TNF-α, r=0.68) and hemolysis indicators (reticulocytes and LDH, r=0.61). A negative correlation between MDA and TAC (r=-0.55) confirmed oxidative stress imbalance in both disorders. Ferritin showed moderate correlation with LDH (r=0.42), suggesting iron overload contributes to hemolysis in thalassemia (Table 6).

Discussion

Our study confirmed that microcytic hypochromic anemia (MCV 65.3 fL, MCH 20.1 pg) is characteristic of thalassemia, while SCD patients exhibited normocytic anemia with higher reticulocytosis (12.3% vs 5.8%, p<0.001). These findings align with previous studies [17,18], where thalassemia patients showed severe microcytosis due to impaired globin chain synthesis, whereas SCD patients had elevated reticulocytes due to chronic hemolysis.

The RDW was significantly elevated in both groups (thalassemia: 22.5%, SCD: 19.2%) compared to controls (13.1%, p<0.001), consistent with studies by Musallam, et al. (2021) [19], suggesting that RDW is a sensitive but nonspecific marker for hemoglobinopathies. However, MCV ≤72 fL demonstrated excellent diagnostic accuracy (AUC 0.92, 94% specificity) for thalassemia, supporting its use as a first-line screening tool in resource-limited settings.

Thalassemia patients had markedly elevated ferritin (1850 ng/mL) due to transfusional iron overload, whereas SCD patients showed moderate elevation (450 ng/mL), likely due to chronic inflammation and hemolysis. These results correlate with studies by Thein (2018) [20], where iron overload in thalassemia was linked to increased oxidative stress and organ damage.

Hemolysis markers (LDH, bilirubin, haptoglobin) were significantly elevated in both disorders but more pronounced in SCD (LDH 620 U/L vs. 480 U/L, p<0.001). This aligns another study [21], who reported that intravascular hemolysis in SCD contributes to endothelial dysfunction and vaso-occlusive crises. The undetectable haptoglobin in thalassemia further supports its role as a marker of severe extravascular hemolysis.

SCD patients exhibited higher inflammatory markers (IL-6: 25.1 pg/mL, TNF-α: 32.4 pg/mL) compared to thalassemia (IL-6: 12.3 pg/mL, TNF-α: 18.6 pg/mL, p<0.001). This finding is consistent with one study [21], who linked chronic inflammation in SCD to vaso-occlusion and tissue damage.

Oxidative stress was more severe in SCD, with higher MDA (8.2 nmol/mL) and lower TAC (0.62 mmol/L) compared to thalassemia (MDA: 5.8 nmol/mL, TAC: 0.85 mmol/L). This supports previous evidence [22,23] that HbS polymerization generates reactive oxygen species, exacerbating cellular damage. Thalassemia patients, despite lower inflammation, still showed significant oxidative stress due to iron-mediated Fenton reactions [24].

The ROC curve analysis revealed MCV ≤72 fL as the most effective discriminator for thalassemia, demonstrating excellent diagnostic accuracy with an AUC of 0.92. This finding strongly supports the use of MCV as a primary screening tool in clinical settings. For SCD, IL-6 ≥18 pg/mL emerged as a more specific inflammatory marker with an AUC of 0.79, indicating its potential utility in identifying disease-related complications.

The combination of MCV and RDW measurements appears particularly valuable for thalassemia screening in endemic regions. This approach could enhance detection rates while maintaining cost-effectiveness in resource-limited healthcare systems. Our data suggest that ferritin levels ≥800 ng/mL serve as a reliable indicator of significant iron overload in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients, which is crucial for clinical monitoring and chelation therapy decisions [25].

The inflammatory markers IL-6 and TNF-α showed promising prognostic potential for SCD complications, particularly for predicting vaso-occlusive crises and acute chest syndrome. These findings align with international guidelines but importantly provide region-specific cut-off values that account for potential variations in Bangladeshi populations due to nutritional factors and other environmental influences.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of hematological, biochemical, and immune markers in thalassemia and sickle cell disease (SCD), offering valuable insights for their differential diagnosis and clinical management. Our findings demonstrate distinct biomarker profiles that can aid in distinguishing these hemoglobinopathies, particularly in resource-limited settings where advanced diagnostic tools may be unavailable.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of our study design warrant consideration. The single-center nature of the research may affect the generalizability of our findings to broader populations. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to track biomarker changes over time or establish causal relationships between the measured parameters and disease progression.

An important limitation was our inability to account for potential genetic modifiers, such as alpha-thalassemia co-inheritance in SCD patients, which could influence clinical presentation and biomarker levels. Future research should prioritize multi-center validation studies to confirm our proposed diagnostic cut-offs across diverse populations.

There is significant potential for exploring novel biomarkers, including microRNAs and endothelial dysfunction markers, which may provide additional diagnostic and prognostic information. Longitudinal studies are particularly needed to better understand the temporal changes in iron overload and inflammatory markers, and their relationship with clinical outcomes in both thalassemia and SCD patients.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors are sincerely grateful to all the patients who participated in this study and generously provided their personal and medical information. Their cooperation and willingness made this research possible.

Author contributions

M.A.S., H.I. and F.A.R., conceptualized, conducted lab and field works, analyzed data, wrote the original draft, reviewed, and edited; M.M.A.S., M.K.M.U., and A.H. conducted research design, validated methodology, analyzed, visualized the data, reviewed, and edited; D.D.R, N.F.S. and S.S.D. validated the methodology, analyzed data, investigated, visualized, reviewed, and proof- read; M.S.B. conceptualization, conducted research design, validated methodology, Conducted analysis, investigated, visualized the data, reviewed, supervised and edited the paper. All authors read and approved the paper for publication.

References

- Kattamis A, Kwiatkowski JL, Aydinok Y (2022) Thalassaemia. The lancet Jun 399(10343): 2310-2324.

- Weatherall DJ (2010) The inherited diseases of hemoglobin are an emerging global health burden. Blood 115(22):4331-4336.

- Piel FB (2016) The present and future global burden of the inherited disorders of hemoglobin. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 30(2): 327-341.

- Williams TN, Weatherall DJ (2012) World distribution, population genetics, and health burden of the hemoglobinopathies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2(9): a011692.

- Taher AT, Weatherall DJ, Cappellini MD (2018) Thalassaemia. Lancet 391(10116): 155-167.

- Cappellini MD, Porter JB, Viprakasit V, Taher AT (2018) A paradigm shift on beta-thalassaemia treatment: How will we manage this old disease with new therapies?. Blood Rev 32(4): 300-311.

- Hokland P, Daar S, Khair W, Sheth S, Taher AT, et al. (2023) Thalassaemia-A global view. Br J of Haematol 201(2): 199-214.

- Cappellini MD, Cohen A, Eleftheriou A, Piga A, Porter J, et al. (2008) Guidelines for the clinical management of thalassaemia [internet].

- Srivastava A, Shaji RV (2017) Cure for thalassemia major–from allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to gene therapy. Haematologica 102(2): 214-223.

- Palmer AC, Bedsaul-Fryer JR, Stephensen CB (2024) Interactions of nutrition and infection: the role of micronutrient deficiencies in the immune response to pathogens and implications for child health. Annu Rev Nutr 44(1): 99-124.

- Jajosky RP, Wu SC, Jajosky PG, Stowell SR (2023) Plasmodium knowlesi (Pk) malaria: A review & proposal of therapeutically rational exchange (T-REX) of Pk-resistant red blood cells. Trop Med Infect Dis 8(10): 478.

- Piel FB, Steinberg MH, Rees DC (2017) Sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med 376(16): 1561-1573.

- Gardner RV (2018) Sickle cell disease: advances in treatment. Ochsner 18(4): 377-389.

- Nath S, Devi M, Rabbi G, Tarafder S, Sharma N, et al. (2020) Clinical Profile and Pattern of Hemoglobinopathies and Thalassaemias: A Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh. IOSR-JDMS 19(2): 60-65.

- Rahman MA, Islam S, Molla Amiruzzaman, Arifa Akram (2022) Variation of Hemoglobin level in Male and Female; single center study of Bangladesh. Journal of National Institute of Laboratory Medicine and Referral Centre Bangladesh 2(1): 11-12.

- Thein SL (2018) Molecular basis of β thalassemia and potential therapeutic targets. Blood Cells Mol Dis 70: 54-65.

- Jaing TH, Chang TY, Chen SH, Lin CW, Wen YC, et al. (2021) Molecular genetics of β-thalassemia: A narrative review. Medicine. 100(45): e27522.

- Ayyash H, Sirdah M (2018) Hematological and biochemical evaluation of β-thalassemia major (βTM) patients in Gaza Strip: A cross-sectional study. Int j health sci 12(6): 18-24.

- Ismaeel H, El Chafic AH, El Rassi F, Inati A, Koussa S, et al. (2008) Relation between iron-overload indices, cardiac echo-Doppler, and biochemical markers in thalassemia intermedia. Am j of cardiol 102(3): 363-367.

- Sultan S, Irfan SM, Ahmed SI (2016) Biochemical Markers of Bone Turnover in Patients with β‐Thalassemia Major: A Single Center Study from Southern Pakistan. Adv hematol 2016: 5437609.

- McGann PT, Nero AC, Ware RE (2017) Clinical features of β-thalassemia and sickle cell disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 1013:1-26.

- Yousuf R, Jahan D, Sinha S, Haque M (2023) Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Thalassaemia Major: A Narrative Review. Advances in Human Biology 13(4): 313-21.

- Mitro A, Hossain D, Rahman MM, Dam B, Hosen MJ (2024) β-Thalassemia in Bangladesh: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Thalassemia Reports 14(3): 49-59.

- Pace BS, Ofori-Acquah SF, Peterson KR (2012) Sickle cell disease: genetics, cellular and molecular mechanisms, and therapies. Anemia 2012:143594.

- Sabath DE (2017) Molecular diagnosis of thalassemias and hemoglobinopathies: an ACLPS critical review. Am j clin pathol 148(1): 6-15.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.