Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

A Study of and a Proposal for Correcting Non- Compliance in the Dietary Management of Type 2 Diabetes in a Select Population

*Corresponding author: Charles H McGowen, One Health Ohio, Community Health and Dental Center, Section of Internal Medicine, Youngstown, USA.

Received: December 31, 2019; Published: January 16, 2020

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2020.06.001098

Background

The purpose of performing this study was to discover through interviews, and thereby objectively establish, the degree of dietary compliance which an inner-city sub-set of type 2 diabetics maintains in conjunction with prescription drug therapy. This was thought necessary in order to ascertain whether or not a proactive and pace setting, programmed approach to afford them healthier and more affordable food choices would improve the outcomes of their hemoglobin A1C monitoring, provide weight reduction and ultimately reduce the severity and number of chronic diabetic complications, i.e. cardiovascular, renal, visual, gastrointestinal, dermatologic and neurological diseases.

According to the recently published Ohio Diabetes Action Plan 2018 [1] “Diabetes represents a significant burden in the state of Ohio. In 1996, 1 in 20 Ohio adults had diabetes; today 1 in 9 do. There are significant racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the prevalence of diabetes in Ohio, and the financial burden is costly” (Ohio Department of Health, 2018). Our demographic represents, and thereby focuses upon, those very disparities sited in the action plan and thus stresses the relevant importance of this study and the reasonable solutions that we will propose [2] .

Methods

Seventy-one patients, ages 24 to 73, were selected randomly from our clinicians’ schedules in each of four separate inner-city clinics (owned and operated by One Health Ohio; a Federally Qualified Healthcare Center) located in Northeastern Ohio (NEO). Permission having been granted by the patients’ clinicians, the subjects were then interviewed by one of two medical or pre-medical students following a routine office visit [3] . Those patients were asked to be honest and forthright regarding their actual eating habits since the information was part of a non-punitive study involving other diabetics who were likely battling the same impediments to eating a healthy diet as were, they. The patients were asked to cite the number of meals consumed per day, the food groups chosen, and relative amounts eaten during those meals, as well as the number and types of snacks they ate [4] . Included were questions concerning the volumes of soda pop and other beverages consumed during an average 24-hour day? After patients shared their average portions per meal and snack, the website nutritionix.com was used to convert their food into grams of macromolecules (including carbohydrates, 4 calories/gm., fats 9 calories/gm., and proteins 4 calories/gm.). Data analysis and graphics were done using various libraries on a Jupyter Notebook using Python 3.7.4.

Results

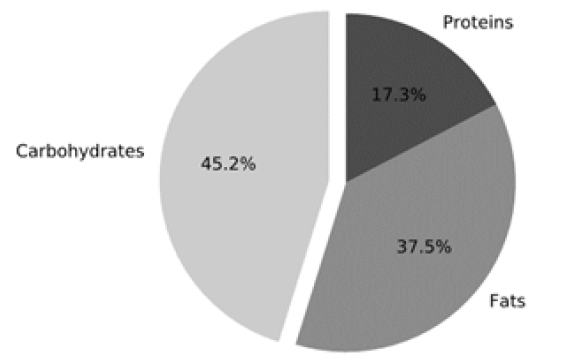

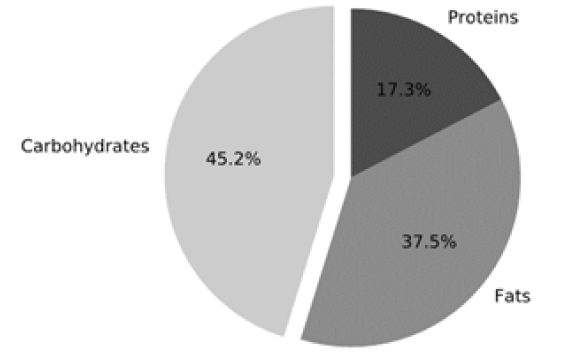

(Figure 1) illustrates the average amount of each macronutrient consumed by the interviewed patients per day, in grams. The USDA sets a Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) of 130 grams of carbohydrates (USDA, 2005). The patients in our study with diabetes surpassed this amount by 35 grams. (Figure 2) depicts the average percentage of calories per macronutrient consumed per day. The CDC recommends that people with diabetes attempt to get nearly 45% of their daily calories from carbohydrates (CDC, 2019). The ADA recommends limiting fat calories to between 20 and 35% and proteins to make up the balance. On average, our patients’ caloric intake is comprised of 45% carbohydrates, 38% fats, and 17% proteins. It is worthy of note that the patients did not significantly surpass the average percentage per diem; however, they exceeded the gross amount in grams by over two servings equaling 30 grams of carbohydrates, or 120 calories per day.

Figure 1: This figure shows the average amount, in g, of each respective macronutrient consumed by patients.

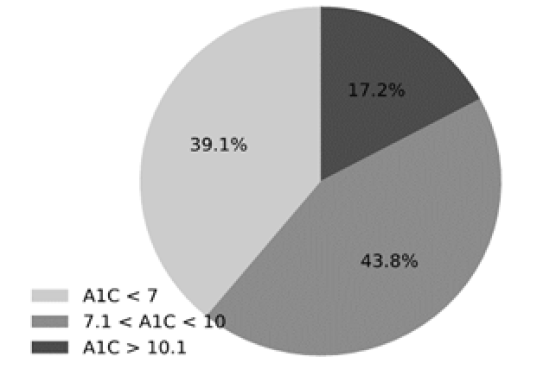

Figure 3: This figure shows the breakdown of patients’ Hb-A1Cs as controlled (<7), or uncontrolled (>7, with >10.1 being severely uncontrolled).

As shown in (Figure 3), only 39% of patients had desirable Hb- A1C levels under 7%, with the remaining 59% of patients being uncontrolled diabetics [5] . These data suggest that blood sugars are not adequately controlled, despite 99% (70/71) being on medications. One potential explanation of this occurrence makes an appearance in (Figure 2), when considering the percentage calories per day from fats (38%), which exceeds the recommendations set by the USDA. (USDA, 2005). Since less-healthy foods often are higher in fats and higher in carbohydrates, and a qualitative observation shows most items consumed are high in simple carbohydrates, it is likely that patients are consuming the right number of carbohydrates, but not the ideal quality; more complex and fewer simple.

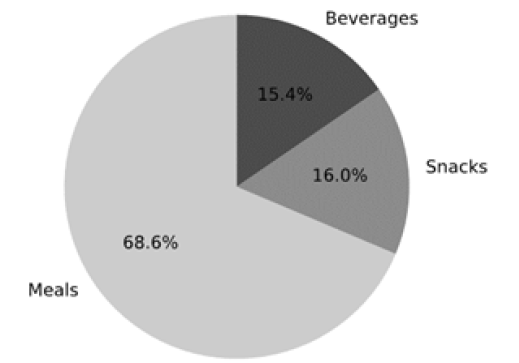

To further verify this finding, (Figure 4) illustrates the average percentage of carbohydrates consumed per source of nutrition (i.e. whether these carbohydrates were eaten during a meal, a snack, or consumed as a beverage). It is noted that 69% of carbohydrates came from meals, 16% from snacks, and 15% from beverages. The CDC recommends that snacks and drinks combined consist of just 1 serving of carbohydrates per day (CDC, 2019) [6] . With an RDA of 130 grams, doing the math tells us that only 12% of carbohydrates should be consumed from snacks and beverages (CDC 2005), compared to the 31% of carbohydrates consumed by the patients interviewed in our study. The fact that patients are over-consuming carbohydrates from snacks and beverages, combined with the high amounts of fats in the patients’ diets, is suggestive of patients choosing simple carbohydrates (i.e. sugar) and saturated fats over higher-quality, more favorable complex carbohydrates and healthier fats such as olive oil.

Discussion

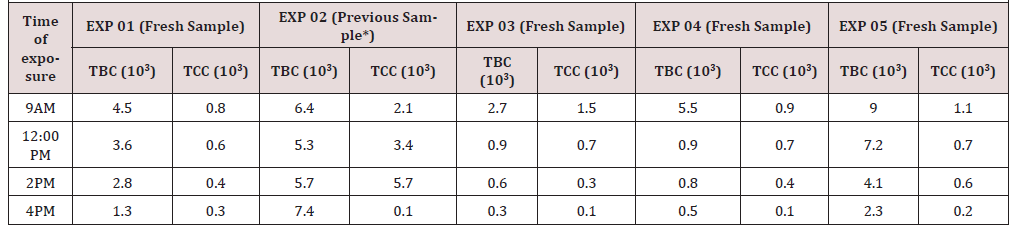

We are unquestionably during an obesity crisis of epidemic proportions in the United States of America and the ever-growing number of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetics in our nation is directly proportional to the increased number of obese persons of all ages and gender. Although T2DM has long been widely diagnosed in adults, the frequency had sadly increased significantly in the pediatric age group by the end of the twentieth century [7] . Depending on the study population, type 2 diabetes now accounts for 8% to 45% of all new cases of diabetes reported among children and adolescents; the differences in numbers depending primarily on which demographic subset was studied; urban, suburban or rural. Prior to 1946 type 2 diabetes was almost unheard of in the pediatric patient population that was younger than age 16. By 1958, 2% of all 16-year-old children were diagnosed with type II diabetes and by 1970 1.5% of 10-year-olds had been discovered to have type 2 diabetes. The rise in those numbers in that pediatric population was mainly attributed to obesity. In 2016 it was estimated that 32% of persons in our US population of 327 million were overweight, and 39.4% obese; of the latter group 6.7 % (27 million) were morbidly obese. Children were included in those totals. The rise in the numbers of pediatric type 2 diabetics thus called for a comparative analysis between them and their adult counterparts (Table 1).

From the observations noted in the above table, it is obvious that the T2DM developing in children and adolescence is a decidedly different kind of disease than that which develops in the adult population and that the more rapid rise of complications signals a greater need for early diagnosis and treatment in the younger subset of non-insulin dependent diabetics. In 1996 there were 11.2 million people living in Ohio; 4.2% (470,000) being diabetic. In 2018 the Ohio population had only risen to 11.7 million, but by then 11.3% (1,300,000) were known to have diabetes (America’s Health Rankings, 2018). The American Diabetes Association (ADA) has found that those people diagnosed with diabetes incur average medical expenditures of $16,752 per year, of which about $9,601 is attributed to their diabetes alone. People diagnosed with diabetes, on average, have medical expenditures approximately 2 and 1/3rd times higher than what their expenditures would be in the absence of diabetes (ADA, 2018). Therefore, since we have seen a more than doubling of our diabetic population in Ohio over the past 22 years, it is obvious that the condition is putting a considerable strain on the state’s healthcare budget. Given the economic toll that both general maintenance care and the long-term complications of diabetes eventuate, our State and national healthcare systems will be economically unsustainable within the next two generations. Thus far, nothing has stemmed the tide of this seemingly insoluble problem. It seems time to take up the challenge, regardless of how daunting it may appear.

The data in this study suggest that our patients consume a large amount of simple carbohydrate (sugar laden), high fat foods. When asked why our subset of patients chose the foods they did, one major motivation involved the lower cost of obtaining these appetite satisfying, high carbohydrate foods (i.e. pasta or other noodles, potatoes, rice, beans, cold cereal, sugar and white bread) as opposed to those foods that are either protein rich (lean meat, eggs, cheese, 2% milk and nuts), olive oils as opposed to other oils and lards, whole grained breads or weight friendly food found in the fresh fruit and vegetable departments of their grocery store.

Conclusion

Based upon our findings, we propose a proactive, pilot project, beginning with volunteer patients in one of the clinics in our NEO locality and the opening of a grocery store there that will serve that select diabetic population in lieu of food stamps, to meet their dietary needs with diabetic and weight friendly, affordable foods. There would be no availability of common snack foods (I.e. chips and candies), deserts (I.e. cakes, pies and ice cream) that our patients seemed to be consuming or beverages other than coffee, tea and 2% or buttermilk milk. Almonds will be provided for snacks since they are a good source of protein and will satisfy mid-meal craving. They will be free to shop elsewhere for non-recommended foods, at their own expense, but we would only ask that they inform us of such breaches so that their resulting weights and HbA1C values can be hash-tagged so as not to skew the curves on the expected success of our project. All patients will be followed monthly for one year; having both weight and hemoglobin A1C levels monitored, the latter at 3-month intervals [8] . Should this pilot program prove effective in lowering both their Body Mass Index (BMI) and hemoglobin A1C values, a recommendation will be extended to the State of Ohio to also take up the challenge through a presentation of our data to both general assembly’s sub-committees on healthcare.

The State is replete with vacant buildings where locally owned grocery stores have gone out of business because of the influx of large, “brand name” national food chain stores. Converting those facilities into State run food distribution centers where Medicaid recipients and other persons who would have been availed the opportunity of food stamps could shop instead, would encourage the purchase of diabetic and weight loss friendly foods at a lower cost to the State, thus reducing the deleterious effects of uncontrolled diabetes and those encountered by non-diabetic obese persons in their cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems. Should Ohio prove successful in favorably altering the bottom line numbers of its diabetic, healthcare expenditures in its Medicaid population, one would hope that the nation would take this successful program on to the fullest extent thus preventing the melting down of our national healthcare programs currently being funded through Medicaid, Medicare and other 3rd party, private insurance organizations [9]. This is not a quick fix for our state or the nation, but it will be beneficial on an individual patient basis as those diabetics who limit their food buying to these health friendly stores begin to notice an overall apparent improvement in their general health and sense of well-being.

Progressive Steps That Lie Ahead

1. Convince the leadership of OHO of the need to establish a diabetic friendly food distribution facility (DFFDF) near or in one of our inner-city clinic locations. The soon opening clinic on the south side of Youngstown, Ohio would be an ideal location for the pilot program.

2. Poll the type 2 diabetics within that clinic who would be willing to forego their food stamps for 12 months in order to qualify for utilizing the newly established DFFDF. Once that number has been determined, the size of the DFFDF can be decided upon by collaborating with local grocers who would be willing to be a part of the project.

3. Work out the logistical details of temporary food stamp withholding in those patients involved in the pilot project.

4. Meet with 2 or 3 local grocers planning the type of food that we recommend and discuss the cost of those foods. Low cost meats, cheese, eggs, grains, nuts, vegetables and fruits, etc. Attempt to get our grocery stocked with the foods we desire at no more than 1% above cost.

5. Once we have good statistics from our pilot program, we can decide upon the future of that lone DFFDF and the desirability of opening branches at other of our clinics.

6. Steps then need to be taken to present our data before the general assembly’s (House and Senate) committees on health and welfare in the hope of encouraging the development of similar programs throughout the state of Ohio as spearheaded by other FQHC’s such as OHO.

7. The announcement of our pilot program, its reasons and goals will be announced through appearances at Radio Station 570 AM on the Dan Rivers morning show.

8. Capri Cafaro may help us get on Fox and Friends in the Morning show.

References

- (2018) Ohio Diabetes Action Plan 2018. Ohio Department of Health.

- (2018) America’s Health Rankings. Trend: Diabetes, Ohio, United States.

- (2018) American Diabetes Association. The Cost of Diabetes.

- (2019) Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes and Carbohydrates.

- D’Adamo E, Caprio S (2011) Type 2 Diabetes in Youth: Epidemiology and Pathophysiology. Diabetes Care 34(2): S161-S165.

- Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Ogden CL (2018) Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Severe Obesity Among Adults Aged 20 and Over: United States, 1960-1962 Through 2015-2016. NCHS Health E-Stats 1(1): 1-6.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL (2017) Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief (288): 1-8.

- Mayer Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, Divers J, Isom S, et al. (2017) Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths 2002-2012. New England Journal of Medicine 376(15): 1419-1429.

- (2005) United States Department of Agriculture. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.