Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Concise Details of RADS

*Corresponding author: Stuart M Brooks, Colleges of Public Health and Medicine, University of South Florida, USA.

Received: November 05, 2019; Published: November 22, 2019

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.06.001029

Abstract

Reactive Airways Dysfunction Syndrome (RADS) is an abrupt-onset asthmatic disorder of a non-allergy origin. Its mechanism relies on innate immunity that permits the airways to deal with non-microbiological constituents. The massive exposure causes a severe airway injury with ensuing detachment of damaged and dead epithelial cells. There is the release of Molecules of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) by stressed or dying cells. Hematopoietic and bone marrow-derived cells migrate to renew the denuded cellular barrier. Soluble growth factors, interleukins, chemokines, arachidonic acid products, and discharges from airway smooth muscle cells aid epithelial and tissue repair. Metalloproteases and extracellular matrix influence the epithelial-to-mesenchymal matrix. Lung macrophages contribute to the repair and influence airway hyperresponsiveness. Airway wall thickening, subepithelial fibrosis, mucus metaplasia, myofibroblast hyperplasia, muscle cells hyperplasia and hypertrophy, and epithelial hypertrophy are characteristic features of the airway remodeling (136-word count).

Introduction

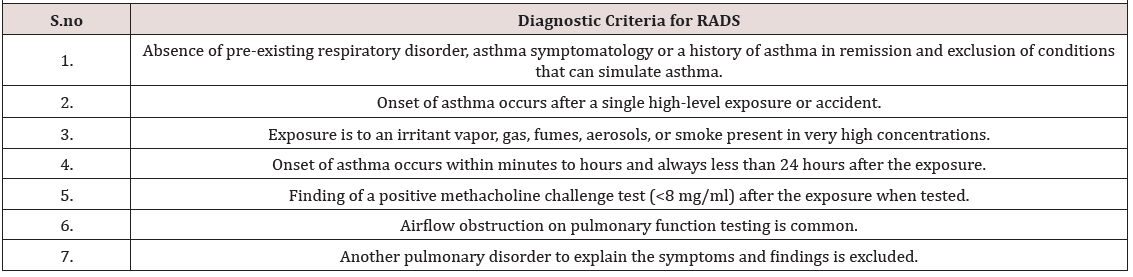

Reactive Airways Dysfunction Syndrome (RADS) is an abrupt-onset asthmatic disorder of a non-allergy origin [1] .RADS development involves the inhalation of a single high-level irritant exposure [2]. Innate immunity plays a critical role in RADS pathogenesis. Implementation of innate immunity permits the airways to deal with non-microbiological constituents arising after a massive irritant inhalation exposure [3, 4, 5]. Allergy, antigenantibody interaction, and actions by immune Th4 lymphocyte are not part of the pathogenetic processes of RADS. Causative agents causing RADS are irritating gases, vapors, aerosols and/or fumes, as well as solvent vapors and acid mists [6, 7]. There generally is need for prompt medical assistance within the first 24 hours after the inhalation exposure [8]. The foremost clinical characteristics of RADS are asthma-like symptoms and nonspecific airway hyperresponsiveness, which may be transient or present for a longer period [9, 10](Table 1) presents the diagnostic criteria of RADS .[2]

Humans and Rads

RADS ensues following an unforeseen or unexpected excessive irritant chemical release. There may be unanticipated explosions or circumstances where there is the sudden accidental release of irritant(s) held under pressure [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Dangerous inhalation events occur in the workplace, the home surroundings, and in various community environmental situations [21]. Accomplishing workplace activities within a confined space having reduced rates of air exchanges and/or a space with reduced fresh air make-up are potentially unsafe situations. Elevated irritating emissions accompany a fire with smoke [22]. Workers engaged in repairing damaged workplace structures or malfunctioning machines are in potential danger. Cleaning activities become risky when a worker is not properly equipped, trained, or aware of potential hazardous risks while performing a job [23].

Adverse pulmonary consequences transpire after accidents involving trains or trucks transporting chemicals. The Bhopal release disaster, involving methyl isocyanate, caused serious lung consequences to workers and surrounding residents [24, 25, 26]. Intentional inhalational casualties occurred because of chemical warfare attacks during World War I and the Iran–Iraq War. A RADSlike condition affected rescue workers involved with the collapse of New York’s World Trade Center on September 11, 2001 [27]. The originally reported causative agents of RADS were uranium hexafluoride gas, floor sealant, spray paint containing significant concentrations of ammonia, heated acid, 35-percent hydrazine, fumigating fog, metal coating remover, and smoke.

When a massive exposure suddenly materializes, like a bolt from the blue, an oncoming exposure cloud quickly gains the attention of witnessing individuals. The expanding suspension may force persons to retreat in fear. Persons in attendance at a worksite or in a community location where a catastrophic massive irritant exposure emerges become frightened and surprised by the unannounced exposure. Panic may ensue. Vocal communications warn of a looming “danger.” Finally, the disastrous exposure envelops victims who breathe in its dangerous constituents, which enter the airway striking the bronchial epithelial cells and mucosal surfaces; both are the first lines of airway defense [5, 28]. Serial bronchial biopsies were obtained on an injured individual at three and 15 days after an accidental workplace inhalational of chlorine gas [29]; bronchial biopsies were also taken at three and five months after the exposure. The earliest bronchial biopsy depicted sloughing of epithelial cells, and infiltration of the submucosa with a fibrinohemorrhagic exudate. Basal and parabasal cells proliferation and deposition of collagen took place early on. Mononuclear cell inflammation, denuded epithelium, and edematous mucosa were reported for the originally reported cases of RADS [1]. Mucosal squamous cell metaplasia, thickening of the basement membrane with reticulum, and collagen-associated bronchial wall fibrosis tended to be later pathological findings [30, 31]. An individual who inhaled sodium hypochlorite and hydrochloric acid disclosed bronchial biopsy pathological findings of cellular destruction, lymphocytic inflammation and subepithelial fibrosis several months after the exposure [30].

An investigation utilizing Sprague-Dawley rats mirrored a human RADS exposure. The laboratory rats sustained a single exposure to 1,500 parts per million of chlorine gas for 5 minutes [32, 33]. The massive exposure caused a severe airway injury with ensuing detachment of damaged and dead epithelial cells; the first line of defense is laid bare [5, 28]. At 24 hours after the exposure, the rat’s airway tissue exhibited a severe injury to the bronchial mucosal with sloughing of damaged or dead epithelial cells, and cellular detachment from the basement membrane. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid identified an initial neutrophilic inflammation. There were mucosal regenerative changes by the third day after the exposure. Cellular regeneration changes persisted for the next 7-14 days. There was the appearance of increasing numbers of mucussecreting cells. Reparative pathological abnormalities disappeared by 90 days after the exposure.

Discussion

Human and animal pathological surveys afford clues to what happens biomedically. Pathological specimens reveal sloughing of damaged and dead epithelial cells; there is and cellular detachment from the basement membrane. In response to the inhalation injury, activated innate repair genes proceed without reliance on an adapted immunity route that requires an antigen-antibody trigger and contributions by Th4 lymphocytes. Hematopoietic and bone marrow-derived cells migrate to renew the denuded cellular barrier [34, 35, 36, 37, 38]. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) are released by stressed or dying cells [39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45]. A variety of cytokines and chemokines, arachidonic and prostaglandin products, and nitric oxide emissions appear [41, 42, 46, 48]. Soluble growthfactors, G-protein-coupled receptor agonists, and liberations from airway smooth muscle cells contribute to epithelial and tissue repair [34, 38, 41, 42, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50]. The mononuclear lymphoid-type cell, noted in RADS, may embody innate lymphoid cells that lack T-cell and B-cell receptors.

Type 2 innate lymphoid cells produce cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-25 or IL-33. These type cells are involved in the pathogenesis of airway hyperreactivity [51,52][51, 52]. RAGE (Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-products) molecules, expressed on macrophages, influence the inflammatory response through DAMPs [38, 40, 53, 54, 55, 56]. RAGE triggers NF-κB (nuclear factor kappalight- chain-enhancer of activated B cells) and numerous MAPKs (Mitogen-activated protein kinases) [57, 58, 59]. NF-κB controls genes involved in inflammation while MAPKs transduce a wide range of cellular responses. HMGB1 (High Mobility Group Box 1), a chromatin-associated, non-histone protein and DAMP, kindles cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, neovascularization, and cellular differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells with RAGE binding [60].

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) influences migration of vascular smooth muscle cells and in “cleanup” operations [42]. The chemokine RANTES (Regulated on Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted) plays a role in the inflammatory process [61, 4]. The amount of RANTES contained in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid is higher in patients with non-allergic asthma[63]. Lung macrophages assist the repair and clean-up processes; and influence airway hyperresponsiveness [64, 65, 6, 67]. The presence of nonspecific airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) is a cardinal feature of RADS. Components of metalloproteases and extracellular matrix improve the epithelial-to-mesenchymal matrix [68-69]. Airway wall thickening, subepithelial fibrosis, mucus metaplasia, myofibroblast hyperplasia, muscle cells hyperplasia and hypertrophy, and epithelial hypertrophy are characteristic features of the airway remodeling response described in cases of RADS [70].

Conclusion

The massive exposure causing RADS initiates detachment of damaged and dead epithelial cells. Molecules of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) enter the extracellular space after being release by stressed or dying cells. Hematopoietic and bone marrowderived cells migrate to renew the denuded cellular barrier. Soluble growth factors, interleukins, chemokines, arachidonic acid products, and discharges from airway smooth muscle cells aid epithelial and tissue repair. Lung macrophages contribute to the repair and influence airway hyperresponsiveness. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells release important cytokines. Proteases and extracellular matrix influence the epithelial-to-mesenchymal matrix. Further airway remodeling entails airway wall thickening, subepithelial fibrosis, mucus metaplasia, myofibroblast hyperplasia, muscle cells hyperplasia and hypertrophy, and epithelial hypertrophy.

References

- Brooks SM, Weiss MA, Bernstein IL (1985) Reactive airways dysfunction syndrome (rads). Chest 88(3): 376-384.

- Brooks SM, Gautrin D, Malo JL (2013) Reactive airways dysfunction syndrome and irritant induced asthma. J Occup Environ Med 55(9): 1118-1120.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, et al. (2002) Cells in their social contex. Innate immunity In: NCBI (editor) Molecular Biology of the Cell Fourth Edition: Garland Science p. 1-10.

- Beutler B (2004) Innate immunity: An overview. Mol Immunol 40(12): 845-859.

- Parker D, Prince A (2011) Innate immunity in the respiratory epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 45(2): 189-201.

- Mc Donald JC, Chen Y, Zekveld C, Cherry NM (2005) Incidence by occupation and industry of acute work related respiratory diseases in the Uk, 1992-2001. Occup Environ Med 62(12): 836-842.

- Shakeri MS, Dick FD, Ayres JG (2008) Which agents cause reactive airways dysfunction syndrome (rads)? A systematic review. Occup Med (Lond) 58(3): 205-211.

- Lemière C, Boulet LP, Cartier A (2016) Reactive airways dysfunction syndrome and irritant-induced asthma. J Occup Environ Med 55(9): 1118-1120.

- Malo JL, L’Archeveque J, Castellanos L, Lavoie K, Ghezzo H, et al. (2009) Long-term outcomes of acute irritant-induced asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179(10): 923-928.

- Takeda N, Maghni K, Daigle S, L'Archevêque J, Castellanos L, et al. (2009) Long-term pathologic consequences of acute irritant-induced asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 124(5): 975-981.

- Franz T, Mc Murrain KD, Brooks SM, Bernstein IL (1971) Clinical, immunologic and physiologic observations in factory workers exposed to b Subtilis dust. J Allergy 47: 170-180.

- Chan Yeung M (2004) Occupational asthma-the past 50 years. Canadian Respiratory Journal 11(1): 21-26.

- Brooks SM (1985) Occupational asthma. In: Weiss EG, Stein M, editors. Bronchial asthma mechanisms and therapeutics. Boston: Little, Brown and Company pp. 461-493.

- Kennedy SM (1992) Acquired airway hyperresponsiveness from nonimmunogenic irritant exposure. Occup Med 7(2): 287-300.

- Barnes PJ (1991) Neurogenic inflammation in airways. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 94(1-4): 303-309.

- Tarlo SM, Broder I (1989) Irritant-induced occupational asthma. Chest 96(2): 297-300.

- Kern DG, Sherman CB (1994) What is this thing called rads? Chest 106(6): 1643-1644.

- Labrecque M (2012) Irritant induced asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 12(2): 140-144.

- Malo JL, Lemiere C, Gautrin D, Labrecque M (2004) Occupational asthma. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine 10(1): 57-61.

- (2007) American College of Chest Physicians. Asthma in the workplace: An accp evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Chest 2007.

- Nemery B (2006) Inhalation injury, chemical. In: B. N, editor. Occupational diseases London: Elsevier Ltd Pp. 208-216.

- Stenton SC, Kelly CA, Walters EH, Hendrick DJ (1988) Induction of bronchial hyperresponsiveness following smoke inhalation injury. Br J Dis Chest 82(4): 436-438.

- Valent F, Mc Gwin JG, Bovenzi M, Barbone F (2002) Fatal work-related inhalation of harmful substances in the united states. Chest 121(3): 969-975.

- Broughton E (2005) The bhopal disaster and its aftermath: A review. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source 4: 1-6.

- Nemery B (1996) Late consequences of accidental exposure to inhaled irritants: Rads and the bhopal disaster. Eur Respir J 9(10): 1973-1976.

- Sriramachari S (2004) The bhopal gas tragedy: An environmental disaster. Current Science 86(7): 905-920.

- Banauch GI, Alleyne D, Sanchez R, Olender K, Cohen HW, et al. (2003) Persistent hyperreactivity and reactive airway dysfunction in firefighters at the world trade center. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168(1): 54-62.

- Laitinen LA, Heino M, Laitinen A, Kava T, Haahtela T (1985) Damage of the airway epithelium and bronchial reactivity in patients with asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 131(4): 599-606.

- Lemiere C, Malo Jl, Boutet M (1997) Reactive airways dysfunction syndrome due to chlorine: Sequential bronchial biopsies and functional assessment. European Respiratory Journal 10(1): 241-244.

- Deschamps D, Soler P, Rosenberg N, Baud F, Gervais P (1994) Persistent asthma after inhalation of a mixture of sodium hypochlorite and hydrochloric acid. Chest 105(6): 1895-1896.

- Gautrin D, Bernstein IL, Brooks SM, PH (2006) Reactive airways dysfunction syndrome, or irritant induced asthma. In: Bernstein IL, Chan Yeung M, Luc-Malo J, D. B, editors. Asthma in the workplace.

- Demnati R, Fraser R, Ghezzo H, Martin JG, Plaa G, et al. (1998) Time-course of functional and pathological changes after a single high acute inhalation of chlorine in rats. Eur Respir J 11(4): 922-928.

- Demnati R, Fraser R, Plaa G, Malo Jl (1995) Histopathological effects of acute exposure to chlorine gas on sprague-dawley rat lungs. Journal of Environmental Pathology, Toxicology & Oncology 14(1): 15-19.

- Fujishima S (2011) Epithelial cell restoration and regeneration in inflammatory lung diseases Inflammation and Regeneration 31(3): 290-295.

- Krause DS (2008) Bone marrow–derived cells and stem cells in lung repair. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5(3): 323-327.

- Davies DE (2009) The role of the epithelium in airway remodeling in asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc 6(8): 678-682.

- Allahverdian S, Harada N, Singhera GK, Knight DA, Dorscheid DR (2008) Secretion of il-13 by airway epithelial cells enhances epithelial repair via hb-egf. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 38(2): 153-160.

- Crosby LM, Waters CM (2010) Epithelial repair mechanisms in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298(6): L715-L731.

- Bianchi ME (2007) Damps, pamps and alarmins: All we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol 81(1): 1-5.

- Vénéreau E, Ceriotti C, Bianchi ME (2015) Damps from cell death to new life. Front Immunol 6: 422.

- Shi Y, Evans JE, Roc KL (2003) Letter to the editor: Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature 425(6957): 516-521.

- Roh JS, Sohn DH (2018) Damage-associated molecular patterns in inflammatory diseases. Immune Netw 18(4): e27.

- Rider P, Voronov E, Dinarello CA, Apte RN, Cohen I (2017) Brief review. Alarmins: Feel the stress. The Journal of Immunology 198(4): 1395-1140.

- Schaefer L (2014) Complexity of danger: The diverse nature of damage-associated molecular patterns. J Biol Chem 289(51): 35237-35245.

- Lands WG (2015) The role of damage-associated molecular patterns (damps) in human diseases. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 15(1): e157-e170.

- Howarth P, Redington AE, Springall DR, Martin U, Bloom SR, et al. (1995) Epithelially derived endothelin and nitric oxide in asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 107(1-3): 228-230.

- Lazaar AL, Panettieri J, Reynold A (2005) Airway smooth muscle: A modulator of airway remodeling in asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 116(3): 488-495.

- Doeing DC, Solway J (1985) Airway smooth muscle in the pathophysiology and treatment of asthma. J Appl Physiol 114(7): 834-843.

- Joubert P, Hamid Q (2005) Role of airway smooth muscle in airway remodeling. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 116 (3): 713-716.

- Chung KF (2000) Airway smooth muscle cells: Contributing to and regulating airway mucosal inflammation?. Eur Respir J 15(5): 961-968.

- Cayrol C, Girard J P (2019) Innate lymphoid cells in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 143(5): 1739-1741.

- Erle DJ, Sheppard D (2014) The cell biology of asthma. J Cell Biol 205(5): 621-631.

- Bierhaus A, Humpert PM, Morcos M, Wendt T, Chavakis T, et al. (2005) Understanding rage, the receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Mol Med 83(11): 876-886.

- Pillai P, Corrigan CJ, Ying S (2011) Airway epithelium in atopic and nonatopic asthma: Similarities and differences. International Scholarly Research Network Allergy 2011: 195846.

- Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, Boulet LP, Boushey HA, et al. (2009) An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Asthma control and exacerbations: Standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180(1): 59-99.

- Fixman ED, Stewart A, Martin JG (2007) Basic mechanisms of development of airway structural changes in asthma. Eur Respir J 29(2): 379-389.

- Zhang W, Liu HT (2002) MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell Research 12(1): 9-18.

- Brasier AR (2006) The Nf-Κb regulatory network. Cardiovascular Toxicology 6(2): 111-130.

- Iwamura C, Nakayama T (2018) Role of CD1D- and MR1-restricted t cells in asthma. Front Immunol 9: 1942.

- Gasparotto J, Girardi CS, Somensi N, Ribeiro CT, Moreira JCF, et al. (2017) Receptor for advanced glycation end products mediates sepsis-triggered amyloid-β accumulation, tau phosphorylation, and cognitive impairment. J Biol Chem 293(1): 226-244.

- Donolon TA, Krensky AM, Wallace MR, Collins FS, Lovett M, et al. (1990) Localization of a human t-cell-specific gene, rantes (d17s136e), to chromosome 17ql1.2-q12. Genomics 6(3): 548-553.

- Maghazachi AA, Al Aoukaty A, Schall TJ (1996) Cc chemokines induce the generation of killer cells from cd56+ cells. Eur J Immunol 26(2): 315-319.

- Novak N, Bieber T (2003) Allergic and nonallergic forms of atopic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 112(2): 252-262.

- Bentley AM, Durham SR, Kay AB (1994) Comparison of the immunopathology of extrinsic, intrinsic and occupational asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 4(5): 222-232.

- Byrne AJ, Mathie SA, Gregory LG, Lloyd CM (2015) Pulmonary macrophages: Key players in the innate defence of the airways. Thorax 70(12): 1189-1196.

- Lambrecht BN (2006) Alveolar macrophage in the driver's seat. Immunity 24(4): 366-368.

- Song C, Luo L, Lei Z, Li B, Liang Z, et al. (2008) Il-17-producing alveolar macrophages mediate allergic lung inflammation related to asthma. The Journal of Immunology 181(9): 6117-6124.

- Brightling CE, Symon FA, SS B, Bradding P, Wardlaw AJ, et al. (2003) Comparison of airway immunopathology of eosinophilic bronchitis and asthma. Thorax 58(6): 528-532.

- Holgate ST, Davies DE, Lackie PM, Wilson SJ, Puddicombe SM, et al. (2000) Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the pathogenesis of asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 105(1): 193-204.

- Elias JA, Zhu Z, Chupp G, Homer RJ (1999) Airway remodeling in asthma. J Clin Invest 104(8): 1001-1006.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.