Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Biomechanical Principles of Multipoint Suture Fixation for Abdominal Wall Reconstruction

*Corresponding author: Jorge de la Torre, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Division of Plastic Surgery and Birmingham V.A. Medical Center, Birmingham, Alabama.

Received:January 21, 2020; Published: January 28, 2020

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2020.07.001115

Introduction

In the United States, approximately 400,000 ventral hernias are repaired every year with an estimated cost of about 3 billion dollars [1] . Ventral hernias are a relatively morbid condition given that an intact abdominal wall is necessary for dynamic activities such as rotation of the torso, respiration, defecation/urination, emesis, and childbirth.

The management of ventral hernias has evolved over the past several decades with advances in technology and knowledge. The first significant improvement was the use of prosthetic mesh reinforcement to simple suture repair alone [2] . As reported by Luijendijk, randomized controlled trials demonstrated a decrease in hernia recurrence rates from 43 percent to 24 percent [3, 4].

Another major advancement was the popularization of the component separation technique as escribed by Ramirez [5] . This technique was found to be particularly useful in the case of large hernias where primary closure of the hernia defect is not possible otherwise. In addition, it eliminates the need for prosthetic mesh and its associated risks, while providing comparable or superior reduction in hernia recurrence [6, 7, 8]. Perhaps more importantly, the component separation technique provides a dynamic abdominal wall reconstruction, using innervated muscle which is critical to reducing hernia recurrence. In addition, component separation procedures provide an anatomic alignment of the muscles, which enhances abdominal wall function.

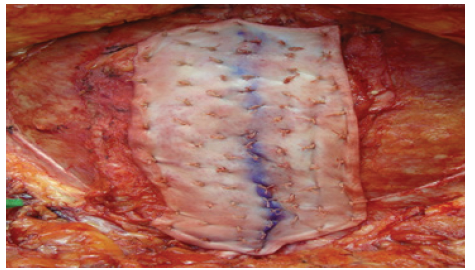

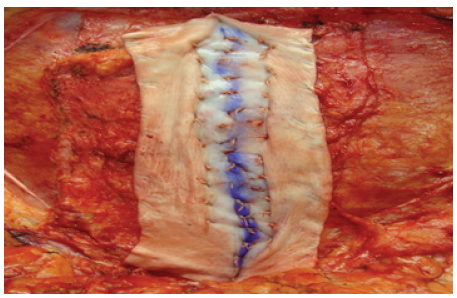

The advent and implementation of biologic mesh or acellular dermal matrices (ADM) has offered an additional valuable tool in the reconstructive armamentarium for ventral hernias [9] . ADM is superior to prosthetic mesh in setting of contaminated and highrisk cases and is a valuable adjunct to the component separation technique [10, 11, 12]. Abdominal wall reconstruction with human acellular dermal matrices (HADM) has also been described [13] . However, since it has increase elasticity as compared to porcine or bovine ADMs, it can leave a significant bulge if used as an inter-positional bridge when myofascial continuity cannot be reestablished (Figure 1A) (Figure 1B)

Figure 1B: Progressive tension stretching the HADM laterally on each side with multiple fixation points with interrupted sutures

Although component separation with biologic mesh reinforcement is effective, there is still not universal agreement as to the technique and location for mesh fixation [14].For standard mesh fixation, the retro-muscular or underlay placements are most commonly used and are associated with lower recurrence rates [15, 16]. There has been some difference in outcomes with different types of fixation for underlay indicating that the method of fixation is important [17] .Placement of sutures lateral to the junction of the linea alba and the anterior rectus sheath have been found to provide the greatest support and tolerance for tissue tension in studies on laparotomy closure [18] .

The multipoint suture fixation offers a technique that combines these advantages for the patient undergoing abdominal wall reconstruction for ventral wall hernia, including the largest and most complex hernias as well as those with infected mesh and soft tissue deficiencies. The multipoint suture fixation technique is a physiologic approach to hernia reconstruction. The technique utilizes wide exposure to avoid injury to the hernia sac or contents. In patients who have had a prior midline incision, that is used. However, in patients without incisions on the abdomen, an abdominoplasty type incision has been found to have a number of advantages [19] . Local anesthesia with epinephrine is injected along the planned incisions to minimize bleeding and facilitate the dissection. The hernia sac and defect are circumscribed, and dissection is continued cephalad to the xyphoid.

Component release incisions are made lateral to the lateral border of the rectus muscles to mobilize the rectus muscles to the midline. The location of the component release is determined by the width of the anterior rectus sheath. It is made at least 8 cms lateral to the midline inset of the rectus sheath. The fascia is released, and the external oblique muscle preserved. In patients in whom the loss of domain is greater, posterior release of the rectus sheath can be added as well. The two abdominal rectus muscles are brought together in the midline with several interrupted 0 Vicryl sutures to ensure alignment of the muscles. This is critical for two reasons, first as indicated previously, a lower recurrence rate is associated with patients in whom myofascial continuity is reestablished. Second, the proper alignment of is important for proper function of the muscles in the actions on the abdominal wall. Even a small deviation of the line of action can have a significant impact on the how effectively muscles function [20] . A looped 1 PDS is used as a continuous running horizontal mattress suture to imbricate the anterior fascia, which is the most effective suture technique [21] . This facilitates securing the anterior fascia just lateral to the junction of the linea alba and anterior rectus sheath where it is strongest [22] .

The intentional selection of HADM to reinforce the abdominal wall fascia offers several advantages. Fascia takes approximately two months to gain 40% of its original strength, but original strength is never regained [23] . The addition of HADM provides not only a temporary increase in tensile strength of the abdominal, but as it integrates, it reinforces the native abdominal wall structure.

As compared to non-crosslinked xenograft ADMs, HADM provide more rapid vascular ingrowth and integration and greater tensile strength of the musculo-fascial interface [24] . The HADM has greater elasticity than non-cross-linked xenograft ADMS or any of the crosslinked ADMs. While this elasticity is a disadvantage for standard inset or interposition graft placement, with the multipoint fixation it offers the advantage of increased abdominal wall compliance.

The wide exposure open approach facilitates careful placement of the HADM. It is secured along the midline imbrication to bolster the inset of the two rectus abdominus muscles. Additional sutures are then placed in an offset row pattern working from the midline out laterally in each direction. Progressive tension sutures have been well-described to fix soft tissue in abdominoplasties to decrease seroma formation [25] . With each row additional traction displaces the HADM laterally as compared to the underlying fascia. This helps fix the HADM to the fascia to decrease the risk of seroma formation between the HADM and the fascia. In addition, the number of sutures strands used for fixation had been demonstrated to have a critical effect on the strength of fixation [26] . Perhaps more importantly, each row progressively offloads the tension on the midline inset of the muscles.

This technique specifically addresses the underlying concept that recurrences most often occur at the mesh-fascia interface. The structural design provides maximum interface of the anterior rectus sheath and the HADM. The progressive tension sutures provide an increased number of fixation points and off-load the inset of the muscles. The clinical results of this technique show that a multipoint fixation suture technique for abdominal wall reconstruction with component separation and onlay biologic mesh is reproducible and effective with low recurrence rates.

References

- Reza ZH, Belyansky I, Park A (2018) Abdominal wall hernia. Curr Probl Surg 55(8): 286-317.

- Bauer JJ, Harris MT, Kreel I, Gelernt IM (1999) Twelve-year experience with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene in the repair of abdominal wall defects. Mt Sinai J Med 66(1): 20-25.

- Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, van den Tol MP, de Lange DC, Braaksma MM, et al. (2000) A comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. N Engl J Med 343(6):3 92-398.

- Burger JW, Luijendijk RW, Wim C J Hop, Jens A Halm, Emiel GG Verdaasdonk, et al. (2004) Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann Surg 240(4): 578- 585.

- Ramirez OM, Ruas E, Dellon AL (1990) "Components separation" method for closure of abdominal-wall defects: An anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg 86(3): 519-526.

- Basoglu M, Yildirgan MI, Yilmaz I, Balik A, Celebi F, et al. (2004) Late complications of incisional hernias following prosthetic mesh repair. Acta Chir Belg 104(4):425- 428.

- Espinosa de los Monteros A, de la Torre JI, Ahumada LA, Person DW, Rosenberg LZ, Vásconez LO (2006) Reconstruction of the abdominal wall for incisional hernia repair. Am J Surg 191:173-177.

- Slater NJ, van der Kolk M, Hendriks T, van Goor H, Bleichrodt RP (2013) Biologic grafts for ventral hernia repair: a systematic review. Am J Surg 205(2):220-230.

- Buinewicz B, Rosen B (2004) A cellular cadaveric dermis (AlloDerm): a new alternative for abdominal hernia repair. Ann Plast Surg 52(2): 188-194.

- Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, de la Torre JI, Marrero I, Andrades P, Davis MR, et al. (2007) Utilization of human cadaveric acellular dermis for abdominal hernia reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 58(3): 264-267.

- Candage R, Jones K, Luchette FA, Sinacore JM, Vandevender D, Re, et al. (2008) Use of human acellular dermal matrix for hernia repair: friend or foe? Surgery 144(4): 703-709.

- Diaz Jr JJ, Conquest AM, Ferzoco SJ, Vargo D, Miller P, et al. (2009) Multi-institutional Experience Using Human Acellular Dermal Matrix for Ventral Hernia Repair in a Compromised Surgical Field. Arch Surg 144(3): 209-215.

- Hood K, Millikan K, Pittman T, Zelhart M, Secemsky B, et al. (2013) Abdominal wall re- construction: a case series of ventral hernia repair using the component separation technique with biologic mesh. Am J Surg 205(3): 322-328.

- Razavi SA, Desai KA, Hart AM, Thompson PW, Losken A (2018) The Impact of Mesh Reinforcement with Components Separation for Abdominal Wall Reconstruction. Am Surg 84(6): 959-962.

- Haskins IN, Voeller GR, Stoikes NF, Webb DL, Chandler RG, et al. (2017) Onlay with Adhesive Use Compared with Sublay Mesh Placement in Ventral Hernia Repair: Was Chevrel Right? An Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative Analysis. J Am Coll Surg 224(5): 962-970.

- Albino FP, Patel KM, Nahabedian MY, Sosin M, Attinger CE, et al. (2013) Does mesh location matter in abdominal wall reconstruction? A systematic review of the literature and a summary of recommendations. Plast Reconst Surg 132(5): 1295-1304.

- Baker JJ, Öberg S, Andresen K, Klausen TW, Rosenberg J (2018) Systematic review and network meta-analysis of methods of mesh fixation during laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Br J Surg 105(1): 37-47.

- Tera H, Aberg C (1976) Tissue strength of structures involved in musculo-aponeurotic layer sutures in laparotomy incisions. Acta Chir Scand 142(5): 349-355.

- Robertson JD, de la Torre JI, Gardner PM, Grant JH, Fix RJ, Vásconez LO, et al. (2003) Abdominoplasty repair for abdominal wall hernia. Ann Plast Surg 51(1):10-16.

- Nussbaum MA, Chaffin DB, Rechtien CJ (1995) Muscle lines-of-action affect predicted forces in optimization-based spine muscle modeling. J Biomech 28(4): 401-409.

- Ishida LH, Gemperli R, Longo MV, Alves HR, da Silva PH, et al. (2011) Analysis of the strength of the abdominal fascia in different sutures used in abdominoplasties. Aesth Plast Surg 35(4): 435-438.

- Tera H, Aberg C (1976) Tissue strength of structures involved in musculo-aponeurotic layer sutures in laparotomy incisions. Acta Chir Scand 142: 349-355.

- (2007) Wound Closure Manual, Ethicon.

- Campbell KT, Burns NK, Rios CN, Mathur AB, Butler CE (2011) Human versus non-cross-linked porcine acellular dermal matrix used for ventral hernia repair: Comparison of in vivo fibrovascular remodeling and mechanical repair strength. Plast Reconstr Surg 127(6): 2321-2332.

- Andrades P, Prado A, Danilla S, Guerra C, Benitez S, et al. (2007) Progressive tension sutures in the prevention of postabdominoplasty seroma: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Plast Reconstr Surg 120(4): 935-946.

- Osei DA, Stepan JG, Calfee RP, Thomopoulos S, Boyer MI, et al. (2014) The Effect of Suture Caliber and Number of Core Suture Strands on Zone II Flexor Tendon Repair; A Study in Human Cadavers. J Hand Surg Am 239(2): 262-268.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.