Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Overall Clinical Outcome of Stereotactic Guided Burrhole-Drainage Versus Craniotomy with Removal of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage

*Corresponding author: Young Zoon Kim, Center for Cerebrovascular Disease and Department of Neurosurgery, Samsung Changwon Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, 158 Paryong-ro, Masanhoewon-gu, Changwon 51353, South Korea.

Received: May 12, 2020;Published: May 20, 2020

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2020.08.001336

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to compare the clinical efficacy and safety of stereotactic guided burrhole-drainage (STBD) and

craniotomy for the treatment of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage(S-ICH).

Method: We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of patients with S-ICH treated in our hospital from December 2017 to November 2018.

Patients were divided into STBD group and craniotomy with hematoma removal group according to different surgical methods. We compared the

basic clinical data, basic conditions before surgery, postoperative status, and related complications of the two groups. The GOS score was used to

evaluate the neurological function, and the activity of daily living (ADL) score was used to evaluate the daily living ability of the two groups.

Results: A total of 120 cases with S-ICH were included in this study, including 78 cases in the STBD group and 42 cases in the craniotomy

group. There were no significant differences in basic clinical data between the two groups of patients at admission. The operation time and hospital

stay of patients in the STBD group were significantly shorter than those in the craniotomy group. There were no significant differences in the risk

of intracranial infection, rebleeding, hydrocephalus, concurrent pulmonary infection, epilepsy and one month postoperative mortality in the two

groups. GCS score increased value ΔGCS was used to judge the degree of consciousness improvement. There was no significant difference in ΔGCS

between the two groups 24 hours and 2 weeks after operation. The follow-up GOS score showed that the clinical prognosis of the STBD group at 1

month was significantly better than that of the craniotomy group, but there was no significant difference between the two groups at 6 and 12 months

after operation. The ADL score showed no significant difference between the two groups at 1 month after surgery, but the ADL score of the STBD

group at 6 and 12 months after surgery was better than that of the craniotomy group.

Conclusion: Stereotactic guided burrhole-drainage combined with urokinase hematoma intraluminal injection has certain advantages over

craniotomy with hematoma removal. It can effectively reduce operation time and hospital stay, improve the symptoms of patients in a short period

of time, and is more conducive to the recovery of patients’ ability of daily living. It is worth promoting in clinic, but its long-term prognosis still needs

further research.

Keywords: Intracerebral Hemorrhage; Stereotaxis; Minimal Invasive; Craniotomy; Outcome

Introduction

Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (S-ICH) is a kind of central nervous system diseases with high mortality and disability rate, which accounts for 15% of all kinds of strokes [1]. In the past 20 years, the incidence of S-ICH increased by nearly 50% [2]. Even it is accompanied by the continuous improvement and progress of treatment concept and treatment means, there is still 40.4% of S-ICH patients died within one month after onset, and the mortality rate is increasing by 0.4% every year [1].While for the surviving patients with S-ICH, severe neurological deficit is still unavoidable. Some studies said that only 26% of patients with S-ICH can complete their daily lives independently within 3 months of onset, most patients cannot take care of themselves, stay in bed for a long time, and even are in the state of plant survival [1].

Surgical treatment is still an effective means to reduce mortality, prolong patient life, and save neurological function. The main purpose of treatment of S-ICH is to reduce intracranial pressure, prevent the formation of brain hernia, and reduce the space occupying effect caused by intracerebral hematoma and secondary brain edema, so as to reduce mortality and improve clinical prognosis. Traditional intracranial hematoma removal has been widely used in clinical practice as the main or even the only surgical method for a long time. However, the traditional removal of intracerebral hematoma by craniotomy is very traumatic, and the brain tissue damage and secondary brain edema caused by the surgery are its disadvantages that cannot be ignored. In recent years, a variety of new surgical methods have been developed and applied in clinical practice, such as small bone flap hematoma clearance, endoscopic hematoma clearance and burr hole drainage, etc. Burr hole trepanation and drainage of intracranial hematoma has been carried out for old times. After its satisfactory effect, neurosurgeons constantly are carrying out the clinical randomized controlled trials of the burr hole trepanation and drainage of intracranial hematoma. However, the results are different, and there is no final conclusion at present. Intracranial pressure monitoring technology, as a new technique has been used in craniocerebral injury operation and intraventricular hemorrhage operation in recent years, it has been proved to be able to guide the peri operative treatment and improve the prognosis of patients, especially stereotactic method using neuro navigation system can help targeting the S-ICH more precisely [3]. But for patients with S-ICH, whether employing burr hole trepanation and hematoma drainage combined with intracranial pressure monitoring and intracavitary urokinase injection can benefit them or not, there is no definitive theory presently because there are few studies.

Therefore, we herein retrospectively analyzed the clinical and follow-up data of patients with S-ICH from December 2017 to November 2018 in our department, to explore the clinical effect of stereotactic guided burrhole-drainage (STBD) combined with intracranial pressure monitoring and urokinase injection in hematoma cavity for S-ICH.

Material and Methods

We conducted a retrospective study on the clinical and followup data of S-ICH admitted in our department from December 2017 to November 2018. All cases were confirmed as S-ICH by plain computed tomography (CT) scan, and the volume of hematoma was more than 30 ml, which had the indication of surgical treatment. The exclusion criteria were followed :(1) CT angiography showed that the patients had intracranial aneurysm, cerebral vascular malformation, moyamoya disease or tumor apoplexy; (2) subtentorial hemorrhage; (3) there has been a subfalx hernia or a foramen magnum hernia; (4) patients had previously taken anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs, pre-operation examination of platelets are less than 50*109 / L, or combined blood system diseases with bleeding tendency; (5) severe organ dysfunction such as heart, liver and kidney. We recorded the patients’ basic information in detail, using Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score to evaluate the neurological function of patients at admission, and record in detail whether the patient has midline structure deviation, hydrocephalus, intraventricular hemorrhage, tobacco and alcohol history, basic diseases, etc.

The hematoma volume in the thalamus was estimated from the CT scans using the formula

A × B × C/2,

where A is the greatest diameter on the largest hemorrhage slice, B is the maximal diameter perpendicular to A, and C is the vertical hematoma depth.

The institutional review boards of the Samsung Changwon Hospital approved this study (SCMC 2019-05-002). All analyses were conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki for biomedical research. The requirement of obtaining informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study and minimal hazard to the participants.

Stereotactic Guided Burr hole-Drainage (STBD) Group

After routine preoperative preparation, we marked the body surface projection of midline, wing point, lateral fissure, and central sulcus using neuronavigation system. According to the preoperative CT scan and body surface positioning, we draw the body surface projection of the patient’s intracranial hematoma on scalp and take the center of the largest layer of the hematoma as the puncture target point. We choose burrhole trephination sites according to the location and shape of hematoma using neuronavigation system as follows: 1)if an oval hematoma located in the basal ganglia, it should be trephined in the temporal area perpendicular to the hematoma; 2)if an oval hematoma located in the basal ganglia and breaks into the lateral ventricle, it should be trephined perpendicular to the hematoma in the temporal area and trephined the contralateral lateral ventricle; 3) If a long strip shape hematoma located in the basal ganglia, it should be trephined parallel to the longitudinal axis of the hematoma in the forehead; 4)if the hematoma is located in the lobes, the trephined site should be selected according to the location of the hematoma and kept away from the important structure or blood vessels.

The operative procedures are as follows: After routine disinfection, towel laying and local infiltration anesthesia, cut a 3-5cm long incision at the trephination site, slice the scalp and subcutaneous tissue layer by layer, stretch the soft tissue with a spreader, burrhole trephination of a hole on the skull and carefully stanch after reaching dura, then cut the dura with a sharp knife, insert the drainage tube along the direction of the hematoma, you can see hematoma flow out when there’s a sense emptiness, continue to insert the drainage tube about 2-4cm, the final insertion depth based on neuronavigation measurement, use syringe to aspirate part of hematoma out, generally 1 / 3 the volume of intracranial hematoma, clamp and close the drainage tube, insert the intracranial pressure probe (Codman, brain parenchyma, model 82236) along the edge of the bone hole about 2cm, then suture the scalp layer by layer, fix the drainage tube and intracranial pressure monitoring probe, finally wrap the wound with sterile dressings. Re-examination of cranial CT and injection of urokinase 20,000-40,000 units into the intracranial hematoma cavity the next day. The course of treatment with urokinase, and removal of drainage tube and intracranial pressure monitoring probe should be determined according to the cranial CT review. The operation of craniotomy hematoma removal group were according to the routine of craniotomy.

Determination of the Prognostic Value

All patients were recorded the GCS scores 24 hours and 2 weeks after operation, and calculated the increased value compared to admission which recorded as Δ GCS. At the same time, we record whether there was intracranial infection, rebleeding, hydrocephalus, epilepsy, pulmonary infection, or death after operation. The follow-up data of patients in 1, 6 and 12 months after operation were recorded. Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score was employed to evaluate the neurological function, and ADL score was employed to evaluate the ability of daily living of patients.

Statistical Analysis

Measurement data was presented as the average of at least triplicate samples and as the mean ± standard deviation and tested with Student’s t test. Counting data was presented as percentage and tested with Chi-square Test. GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) were used for statistical analysis. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

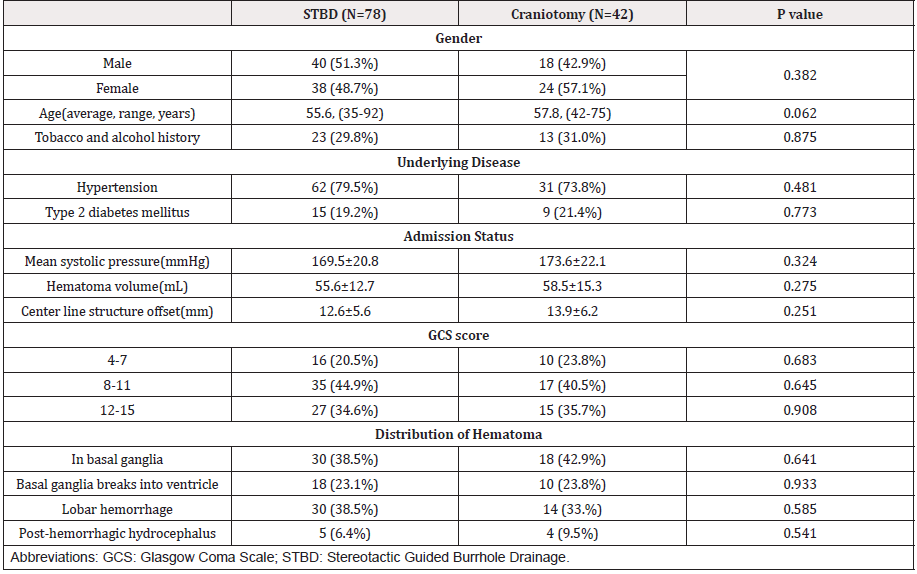

There were 78 cases included in the STBD group, 40 males and 38 females with an average age of 55.6 years (35-92 years). Among the 78 patients included, 62 patients (79.5%) had hypertension, 15 patients (19.2%) had type 2 diabetes and 23 patients (29.8%) had tobacco or alcohol history for more than 10 years. There were 27 cases with a GCS score between 12-15, 35 cases between 8-11 and 16 cases between 4-7 on admission. The mean systolic blood pressure of 78 cases was (169.5 ± 20.8) mmHg. The hematoma of the 78 cases were located as follows, 30 cases(38.5%) in basal ganglia, 18 cases(23.1%) in basal ganglia with breaking into ventricle and 5 cases (6.4%) had hydrocephalus after hemorrhage, 30 cases (38.5%) in lobes including 10 cases of frontal lobe, 12 cases of parietooccipital lobe and 8 cases of temporal lobe. The average volume of hematoma before operation was (52.6 ± 12.7) ml, and the deviation of midline structure was (12.6 ± 5.6) mm.

There were 42 cases in the group of intracranial hematoma removal by craniotomy, including 18 males and 24 females, with an average age of 57.8 years (42-75 years). 31 cases (73.8%) were complicated with hypertension, 9 cases (21.4%) with type 2 diabetes and 13 cases (31.0%) had tobacco or alcohol history for more than 10 years. There were 15 cases with a GCS score between 12-15, 17 cases between 8-11 and 10 cases between 4-7 on admission. The systolic blood pressure on admission was (173.6 ± 22.1) mmHg. The distribution of hematoma was as follows: 18 cases (42.9%) in the basal ganglia, 10 cases (23.8%) in the basal ganglia with breaking into ventricle and 4 cases (9.5%) had hydrocephalus after hemorrhage, 14 cases (33%) in lobes, including 3 cases of frontal lobe, 7 cases of parietooccipital lobe and 4 cases of temporal lobe. The average volume of hematoma before operation was (64.5 ± 15.3) ml, and the deviation of midline structure was (13.9 ± 6.2) mm. The detailed basic clinical data of two groups were shown as Table 1.

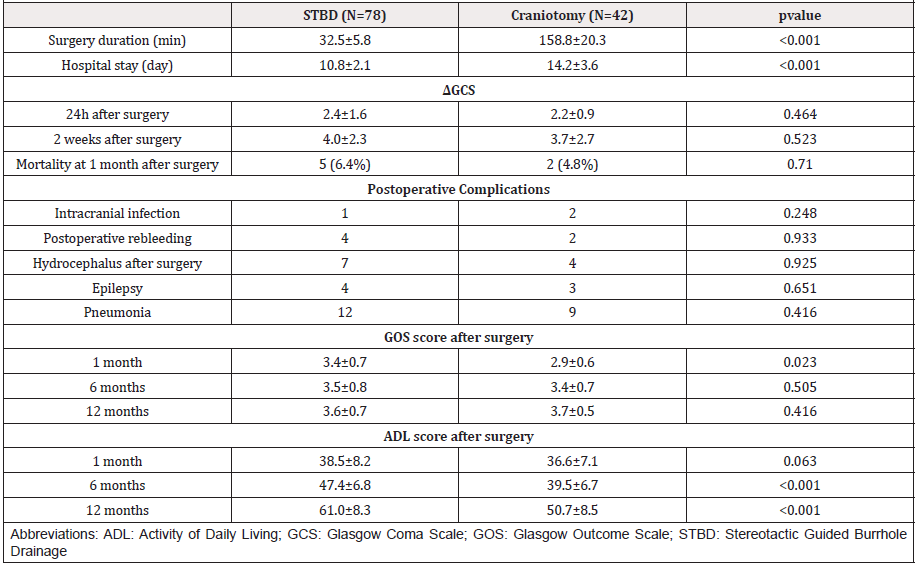

We compared the operative time, hospital stay, postoperative complications, postoperative mortality, postoperative recovery of consciousness, neurological function, and ADL between the two groups, the results were as follows. The average operation time of STBD was (32.5 ± 5.8) minutes, which was significantly shorter than (158.8 ± 20.3) minutes compared with craniotomy. The average hospital stay of the two groups was (10.8 ± 2.1) days versus (14.2 ± 3.6), which indicated that the former group has obvious advantage. By comparing the postoperative complications, we found that there was no significant difference in the incidence of postoperative intracranial infection, postoperative rebleeding, pulmonary infection, postoperative hydrocephalus and epilepsy between the two groups.

There was no significant difference in mortality between the two groups in one month after operation. We count and analyze the difference of GCS score between two groups at 24 hours and 2 weeks after operation with the score of at admission, the ΔGCS, as to evaluate the recovery of consciousness. The results showed that there was no significant difference in Δ GCS between the two groups at 24 hours and 2 weeks after operation. We analyzed the follow-up results of 1 month, 6 months and 12 months after operation, GOS score showed that the prognosis of STBD group was significantly better than that of craniotomy group at 1 month after operation, however a longer-term follow-up found that there was no significant difference in clinical prognosis between the two groups at 6 months and 1 year after operation. ADL score showed that there was no significant difference between the two groups at 1 month after operation, while the ability of daily living in the group of STBD was higher than that in the group of craniotomy in 6 months and 12 months after operation. The postoperative and follow-up data of the two groups are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

Previous reports suggested that the occupying effect of intracranial hematoma was the main factor affecting the prognosis of patients. Studies in recent years suggest that the secondary pathological changes of brain tissue around hematoma may play a decisive role in the prognosis of patients. The secondary pathological change led to increased glutamate release, which was cytotoxic to peripheral neurons. Therefore, it is particularly vital to clear the intracranial hematoma as soon as possible [4,5]. Compared with STBD, removing of hematoma by craniotomy can maximize the removal of hematoma, quickly eliminate the occupying effect of intracranial hematoma, reduce the edema of peripheral brain tissue, however it is unknown whether the patient ’s prognosis has really improved. Not all patients with cerebral hemorrhage can benefit from craniotomy, especially for those patients whose intracerebral hemorrhage located in functional area, such as intracapsular or basal ganglia [6]. In addition, the removal of hematoma by craniotomy is more traumatic and takes longer. In order to clear the hematoma and stanch bleeding, the brain tissue around the hematoma will be damaged more or less, which may in turn aggravate the brain edema. In some reports the clinical effects of craniotomy and conservative treatment were compared, which confirmed that there was no significant difference in clinical effects between them, even for some severe patients with large hematoma volume and low preoperative score, the mortality rate of patients undergoing craniotomy hematoma removal is as high as 64.7% [7]. It has also been found that early craniotomy does not increase mortality and disability, however, the follow-up observation also lacks sufficient evidence to prove that early operation can effectively improve the prognosis of patients, especially for patients conscious, with a hematoma between 10-30 ml, and without ventricular hemorrhage [8]. Therefore, in view of the advantages and disadvantages of craniotomy, there were always some concerns in clinical decision-making. In the STBD operation as minimal invasive methods, most patients can be operated under local anesthesia. It has been reported that general anesthesia has a greater impact on the prognosis of patients with cerebral hemorrhage. Compared with patients with local anesthesia, patients undergoing general anesthesia have higher postoperative mortality and respiratory complications [9]. In STBD operation, we draw out part of the hematoma with a syringe slowly and steadily, it can also reduce the intracranial occupying effect and intracranial pressure to a certain extent, and also reduce the occurrence of secondary pathological injury. In this study, 78 patients with STBD were treated with intracavitary urokinase injection at a dose of 30000-50000 IU / day, according to the remaining hematoma on CT, the average time of urokinase injection was 6.8 days. There was 1 case of postoperative intracranial infection and 4 cases of postoperative rebleeding, but there was no significant difference between the above indexes compared with craniotomy. Therefore, we do not think that the above complications are related to the injection of urokinase into the hematoma cavity. The STBD combined with intracavitary injection of plasminogen activator can not only accelerate the drainage of hematoma, but also effectively alleviate brain edema around hematoma, so it can quickly relieve intracranial hypertension and reduce the incidence of secondary brain injury to a certain extent, and its safety and clinical effect are worthy of affirmation [10]. At present, intracranial pressure monitoring is mostly used in patients with craniocerebral trauma and intraventricular hemorrhage, but there are few studies on the combination of hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage and intracranial pressure monitoring. It can objectively reflect the changes of intracranial pressure and provide clues for clinical decisionmaking [11]. In this study, 78 patients underwent minimally invasive drilling and drainage were guided by CT images before operation. Due to the difference of scanning baseline, the increase of hematoma before puncture, the position of drainage tube may be inappropriate. The drainage tube was at the edge of hematoma in few cases, which has negative effect on drainage and security risks for intraluminal urokinase injection.

In addition, for a few patients with irregular shape of hematoma, it is often difficult to implement the puncture. At present, there is a lack of comparison between the clinical effect of STBD and craniotomy. Some scholars have found that STBD cannot effectively reduce the mortality of patients, but it can effectively improve the long-term prognosis of patients [12]. Based on the study of hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage patients, it is found that STBD has a significant effect and can achieve good neurological function recovery. For some patients younger than 60 years old, it can significantly reduce mortality [13]. Intracavitary injection of plasminogen activator into hematoma has been repeatedly reported to be safe and effective [14-17]. Our study also found that intracavitary injection of urokinase in hematoma did not increase the risk of rebleeding, and its safety should be affirmed. Therefore, we believe that STBD combined with intraluminal injection of urokinase can effectively shorten the operation time and hospital stay and reduce hospitalization costs. In the short-term follow-up observation, we found that STBD as minimal invasive methods can effectively improve the symptoms of patients in a short period of time, which is more conducive to the recovery of patients’ nerve function and daily living ability. Compared with the traditional craniotomy, it is worthy of clinical application, but its long-term prognosis needs further study.

Conclusion

Based on the analysis of our study and the findings of the related references, we could conclude that STBD was effective and safe approach for treatment of S-ICH. This approach has the advantages of minimal invasiveness and shorter operation time and hospital stay. It can improve the symptoms of patients in a short period of time and is more conducive to the recovery of patients’ ability of daily living.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Young Min Kim, M.D. and Mi Ok Sunwoo, M.D. (Department of Radiology, Samsung Changwon Hospital) for their review of neuroradiological images, and Young Wook Kim, M.D. (Department of Biostatistics and Occupational Medicine, Samsung Changwon Hospital)for statistical advice.

Disclosure

The authors report no other conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Funding

This research was supported financially by Korea United Pharm Ltd.

References

- Gross BA, Jankowitz BT, Friedlander RM (2019) Cerebral Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage: A Review. JAMA 321(13): 1295-1303.

- Deopujari C, Shaikh S (2018) Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage.Neurol India 66(6):1704-1705.

- Liu M, Yang ZK, Yan YF, Shen X, Yao HB, et al. (2020) Optic Nerve Sheath Measurements by Computed Tomography to Predict Intracranial Pressure and Guide Surgery in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. World Neurosurg 134: e317-e324.

- Weimar C, Kleine Borgmann J (2017) Epidemiology, Prognosis and Prevention of Non-Traumatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Curr Pharm Des 23(15): 2193-2196.

- Xu X, Zheng Y, Chen X, Li F, and Zhang H, et al. (2017) Comparison of endoscopic evacuation, stereotactic aspiration and craniotomy for the treatment of supratentorial hypertensive intracerebral haemorrhage: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 18(1): 296.

- Ziai W C, Carhuapoma J R (2018) Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 24(6): 1603-1622.

- Hackenberg KA, Unterberg AW, Jung CS, Bösel J, Schönenberger S, et al. (2017) Does sub occipital decompression and evacuation of intraparenchymal hematoma improve neurological outcome in patients with spontaneous cerebellar hemorrhage? Clin Neurol Neurosurg 155: 22-29.

- Ge C, Zhao W, Guo H, Sun Z, Zhang W, et al.(2018) Comparison of the clinical efficacy of craniotomy and craniopuncture therapy for the early stage of moderate volume spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage in basal ganglia: Using the CTA spot sign as an entry criterion.Clin Neurol Neurosurg 169: 41-48.

- Brinjikji W, Pasternak J, Murad MH, Cloft HJ, Welch TL, et al. (2017) Anesthesia-Related Outcomes for Endovascular Stroke Revascularization: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.Stroke 48(10): 2784-2791.

- Ziai WC, McBee N, Lane K, Lees KR, Dawson J, et al. (2019) A randomized 500-subject open-label phase 3 clinical trial of minimally invasive surgery plus alteplase in intracerebral hemorrhage evacuation (MISTIE III). Int J Stroke 14(5): 548-554.

- Ren J, Wu X, Huang J, Cao X, Yuan Q, et al. (2020) Intracranial Pressure Monitoring-Aided Management Associated with Favorable Outcomes in Patients with Hypertension-Related Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res.

- Carvi YNM (2005) Why, when, and how spontaneous intracerebral hematomas should be operated. Med Sci Monit 11(1): RA24-A31.

- De Oliveira MA (2020) Surgery for spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care 24(1): 45.

- Wen AY, Wu BT, Xu XB, Liu SQ (2018) Clinical study on the early application and ideal dosage of urokinase after surgery for hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 22(14): 4663-4668.

- Hanley DF, Thompson RE, Muschelli J, Rosenblum M, McBee N, et al. (2016) Safety and efficacy of minimally invasive surgery plus alteplase in intracerebral haemorrhage evacuation (MISTIE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 15(12): 1228-1237.

- Abdelmalik PA, Ziai WC (2017) Spontaneous Intraventricular Hemorrhage: When should intraventricular tPA be considered? Semin Respir Crit Care Med 38(6): 745-759.

- Kim YZ, Kim KH (2009) Even in patients with a small hemorrhagic volume, stereotactic-guided evacuation of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage improves functional outcome. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 46(2): 109-115.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.