Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

COVID-19: Initiating the Expansion of Telemedicine in Neurosurgery

*Corresponding author: Jason H Huang, MD, Department of Neurosurgery, Baylor Scott & White Health, 2401 S. 31st Street, Temple, Texas 76508, USA

Received: May 28, 2020; Published: June 03, 2020

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2020.09.001359

Abstract

Objective: As COVID-19 spreads around the world, so does telemedicine across many medical specialties including neurosurgery. Given the unique patient population in neurosurgery, arising opportunities for integration and expansion of telemedicine into neurosurgery practice come with challenges for both the patient and the provider.

Methods: A literature review has been performed, and a survey has been sent out to neurosurgery providers in Texas to determine if providers are satisfied with the current state of telemedicine in their clinical practice.

Results: Patients who live far away from a medical center have cited increased convenience when routine postoperative visits have been converted to telemedicine. For providers, challenges have arisen in performing physical exams, especially when performing detailed neurological exams in the diagnosis of a spine disorder. Survey results of neurosurgery providers have revealed mixed opinions since the initiation of telemedicine.

Conclusion: Although it is unclear what role telemedicine will have after the social distancing restrictions are lifted, many providers surveyed have expressed interest in keeping telemedicine in their clinical practice.

Keywords: Coronavirus; COVID-19; Neurosurgery; Telemedicine

Introduction of Telemedicine

Since the emergence of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December of 2019, the novel coronavirus has quickly spread across the globe with the number of COVID-19 cases growing exponentially. Although the majority of patients during this pandemic are seeking experts in the management of respiratory disorders, there remains patients with neurological problems requiring evaluation by neurosurgical providers. Recommendations and regulations set forth by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the federal government, state governments, and healthcare systems have imposed stringent restrictions on physical contact (social distancing). It is becoming increasingly difficult for patients with non-emergent neurosurgical problems to be evaluated.

The use of telemedicine is not unfamiliar to certain specialties within neurosurgery, especially emergent cerebrovascular care. Beginning in the late 1990s, some patients presenting with an acute ischemic stroke were assessed remotely by neurologists and neurosurgeons. This early experience developed into modern touch screen platforms allowing for two-way audiovisual communication between the provider and patient [1]. Also, remote interpretations of computed tomography (CT) angiography and CT perfusion of the brain are now widely adopted in endovascular neurosurgery. Some smartphone applications can display the results of the CT angiogram with similar accuracy to a hospital-based work station [2]. On the other hand, as telemedicine continues to expand during the COVID-19 crisis, certain subspecialties of neurosurgery are experiencing telemedicine for the first time. Consequently, new opportunities and challenges are being discovered by the patient and the provider with the expansion of telemedicine into this field. With the intention to determine if patients and providers are satisfied with the expansion of telemedicine, a survey has been sent out to neurosurgery providers in the state of Texas, and a literature review has been performed. The opportunities, challenges, and the prospect of telemedicine in neurosurgery have been discussed.

Methods

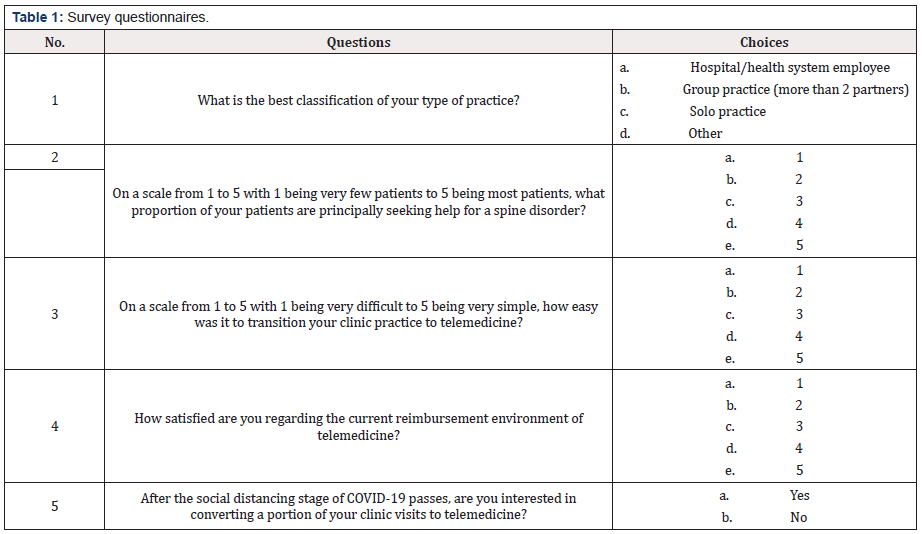

A questionnaire has been sent out to the nation’s secondlargest organized group of neurosurgeons, the Texas Association of Neurological Surgeons (TANS) (Table 1). The questionnaire consists of five questions of interest. First, neurosurgery practices have been put into four categories, i.e., hospital/health system employed or academic practice, group practice with more than two partners, solo practice, and other. Second, we asked the surveyed providers the proportion of patients seeking help for a spine issue as this group of disorders requires a more complex physical examination. Third, the surveyed neurosurgeons scaled the level of complexity in transitioning clinic practice to telemedicine. Then the satisfaction of reimbursement in telemedicine was scaled. The second to the fourth questions are matrix types with a scale from one to five, with one being the least and five being the most. For matrix types of survey questions, the mean of the scale has been obtained, which was then divided by 5 to obtain the percentage in the corresponding question category. Finally, the surveyed surgeons responded with whether they would be interested in converting a portion of clinic visits to telemedicine. With the results of responses in hand, we performed a literature review and examined the opportunities, challenges, and the prospect of telemedicine in neurosurgery.

Results

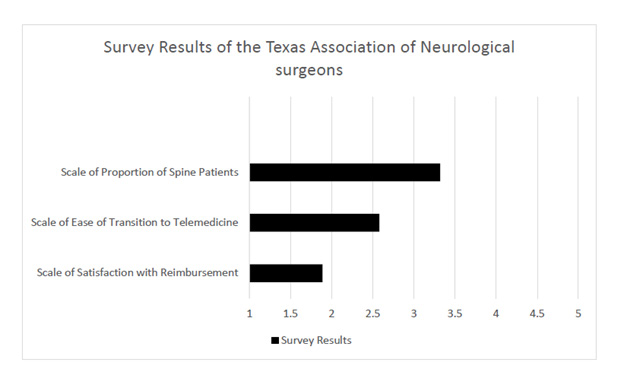

Of the 39 responders, 54.85% (n=21) was a hospital/health system academic employee, 23.08% (n=9) were in a group practice (more than two partners), 15.38% (n=6) were in a solo private practice, and 7.69% (n=3) were in other practice (one is retired, one is a medical director, one did not specify). Neurosurgery practice consists of 66.5% of spine disorders (mean scale=3.32, scale from 1 to 5). Since the initiation of telemedicine during the COVID-19 outbreak, neurosurgery providers had a more than average difficulty level (51.6%, mean scale=2.58, scale from 1 to 5) with the transition to telemedicine, and satisfaction rate is 37.7% (mean scale=1.89, scale from 1 to 5) with the reimbursement obtained from telemedicine clinic visits (Figure 1). Interestingly, 68.4% of surveyed neurosurgeons would like to convert a portion of their clinical practice to telemedicine after social distancing restrictions are released.

Discussion

Neurosurgery clinic consists of a wide range of encounters, from initial neurosurgical evaluation, preoperative visit, to postoperative wound care and follow-up. Inevitably, the complexity of each visit is contingent on the specific scenario. Nonetheless, a physical examination with a neurological focus is essential to each neurosurgery visit. As telemedicine separates patient and provider physically, neurological exam becomes unreliable and even impossible for certain assessments. Meanwhile, technical infrastructure demanded by telemedicine calls for professional information technology (IT) support on both ends of healthcare service. These all hinder the transition of traditional neurosurgery clinic visit to a telemedicine platform. The low satisfaction rate in reimbursement for telehealth visit could be a reflection of the limitation of telemedicine in neurosurgery, as a virtual visit prevents a comprehensive evaluation including a thorough physical examination. Intriguingly, the majority of the surveyed neurosurgeons favored converting a portion of their clinic practice to telemedicine. This might be contributed to the flexibility of conducting a telepresence visit.

Opportunities of telemedicine in neurosurgery

A crisis is an opportunity in disguise. The dreadful COVID-19 has been such an opportunity for telemedicine. The COVID-19 pandemic has posed both patients and healthcare providers in great threat through traditional in-person clinic visit. With social distancing being imposed nationwide, many patients and providers have turned to telemedicine for certain outpatient visits, as it efficiently keeps patients and providers connected while maintaining a safe physical distance.

Emergency stroke evaluations via telemedicine have been established and proven to be non-inferior to traditional evaluation. Telemedicine is often well-suited for routine postoperative visits where the patient can report progress, and a simple video wound check can be conducted easily. Thakar et al. [3] found telemedicine to be more cost-effective as measured by patient-perceived utility scores, especially for patients traveling long distances to the medical center in routine postoperative visits after elective spine surgery [3]. Telemedicine postoperative visit was a safe and even desirable alternative by patients in the first ninety days after elective cranial surgeries, including aneurysm clipping, arteriovenous malformation resection, brain tumor resection, and various forms of microvascular decompression [4]. The time and cost savings attributed to telemedicine visits are the major contributing factors leading to higher patient satisfaction scores in regards to routine postoperative or post-hospital discharge follow-up visits [5].

Other types of neurosurgical patients may be well-suited for telemedicine-based initial consultations or follow-up visits. For example, patients harboring small, unruptured intracranial aneurysms that simply need to establish care or schedule an outpatient angiogram with a neurosurgeon may find it ideal to do so with a telemedicine visit. Also, patients with small brain tumors discovered incidentally may benefit from establishing care or seeking long-term follow up with a neurosurgeon with a telemedicine visit. In both of the above examples, if the decision for surgery is made by the neurosurgeon, then a formal in-patient visit complete with the patient’s family is recommended.

Telemedicine has offered patients unique access to the relative scarce neurosurgical resources. Other providers who need a consult can also collaborate with neurosurgeons more easily and efficiently. This is a perfect time for providers, legislatures, medical boards, federal agencies to work together and perfect the telemedicine model by establishing guidelines, regulations, and medical legislature.

It may sound daring, but the robotic surgical system and advanced communication technology have enabled surgeons to perform surgeries remotely. The first remote neurosurgery was reported back in 2018 when a deep brain stimulation was performed by a surgeon 1,800 miles away from the patient through the help of a robotic surgical system equipped with 5G technology [6]. Robotic arms have been developed for vascular interventional treatment and used in abdominal aorta disorders. It might not be long before neurosurgeons can perform neurosurgical procedures thousands of miles away from the patient.

Challenges of telemedicine in neurosurgery

The core of a clinical encounter lies in the physician’s evaluation and recommendations based on a comprehensive medical history, physical exam, and available test results and images. A medical history can be collected through synchronous audio and video communication, test result, and image accessible via the electronic medical chart and imaging system. The most challenging part during a telemedicine visit is the physical examination. Certain neurosurgical conditions produce signs and symptoms that are beyond the scope of telemedicine. Many limitations have been recognized by the practitioner performing detailed neurological exams on patients. A large-scale study has found that the telemedicine-based physical exam is inferior to an in-person physical exam [7].

To perform a better neurological exam via telemedicine, the American Academy of Neurology has shared some tips. Mental status can be easily determined through observation. Speech should be assessed in the sequence of comprehension, naming, and repetition. Visual fields evaluation can be done on the screen, but may require an assistant on the patient’s side. To examine the extraocular muscles, instruct patient to look all the way to the left, right, up, and down without moving the head; to examine visual fixation, instruct patient to focus on camera and rotate head from side to side. Face and tongue can be examined through video. Pupils can be observed with zoom function, however light reflex and fundoscopy won’t be able to be assessed. Gross hearing can be assessed through audio; however, air and bone conduction tests cannot be assessed without an assistant or a tuning fork with the patient. Shoulder shrug symmetry can be observed virtually. Motor strength can be examined with nonconfrontational measures: asymmetry of forearm rolling, digiti quinti sign can be used as signs of arm weakness; examine legs strength by instructing patient to stand up from a sitting position with arms crossed, crouch, heel walk, and plantar walk. The cerebellar function can be assessed with finger to nose test or heal-knee-shin test easily. Sensory exams, reflexes, fundoscopy, muscle tone, strength grades, and vestibular maneuvers that require head movement are difficult to perform without a trained assessor [8].

The area of neurosurgery that might be most hindered by telemedicine is spine disorder since imaging findings may not directly correlate with the patient’s presenting complaints. The physical exam is crucial to patients presenting with severe low back pain to differentiate a spine pathology such as a compressive myelopathy or radiculopathy from an intrinsic hip, sacroiliac joint, or peripheral nerve pathology [9]. Additionally, patients presenting with cauda equina syndrome, a surgical emergency, can accurately be diagnosed only after a detailed physical exam is performed with a careful assessment of a patient’s rectal tone, perineal sensation, and lower extremity strength [10].

Aside from certain aspects of the neurological exam, providers may struggle with obtaining other critical pieces of a patient’s overall health to include current weight, gait, posture, and vital signs. The collection of certain vital signs using over-the-counter equipment may be commonplace for patients with chronic respiratory disease, cardiac conditions, or diabetes, but this requires a purchase that patients seeking an initial consultation with a neurosurgeon may be unable to perform [11].

In addition to the telepresence visit, both patient and provider may come across obstacles pertaining to the infrastructure of telemedicine. Small group and solo practice may not have a dedicated IT source or support to set up the platform required for the telehealth visit. Some patients may have insufficient equipment, internet access, or skills to operate the application for the visit. There could be regulations imposed by the state or federal government restricting telemedicine practice. Providers could be put in a position where they could not comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) completely. The coding, billing, and reimbursement process could be perfected to better serve telehealth visits. These are all challenges that limit the broad adoption of telemedicine in neurosurgery.

Future of telemedicine in neurosurgery

Telemedicine closes the physical gap between providers and patients, among specialists, between educators and students. We already have access to medical resources at our fingertips through smartphones. Soon, in a rural area, we may see a local clinic with a designated room in which a patient can be comprehensively evaluated by a neurosurgeon via telemedicine while assisted by a trained examiner present with the patient. With the advancement of communicating technology and improvement of a robotic surgery system, remote neurosurgery might become the new norm of neurosurgery practice. As augmented reality being introduced into the medical field, patient-physician interaction will become more effective and efficient. Additionally, students from underdeveloped regions can learn advanced neurosurgical knowledge and technique even from thousands of miles away under the establishment of telemedicine. Without a doubt, telemedicine will advance and greatly mobilize limited medical resources and upraise medical education.

Limitations

The survey sample size is small and targeted neurosurgeons that are members of the TANS. This inevitably created selection bias, and the small sample size limit the generalization of the findings. Not all neurosurgeons responded to the surveys. Those who did not respond may present a different picture of telemedicine in neurosurgery. The matrix-type of survey question requests responders to scale from 1 to 5. Responses generated in this way are more subjective; therefore, objective parameters and measurements are warranted in further study.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 outbreak has set the stage for a potential new practice model with telemedicine as an integral part to neurosurgical care instead of an alternative means during times of social distancing. At this time, it is unclear if certain restrictions that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have lifted such as the ability for practitioners to practice across state lines or equal reimbursement for a telehealth visit when compared to an in-person visit of equal complexity level will continue to hold true once the pandemic is over [12].

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health (NIH-R01-NS-067435 awarded to JHH) and Moody Foundation (JHH).

References

- Levine SR, Gorman M (1999) Telestroke: the application of telemedicine for stroke. Stroke 30(2): 464-9.

- Hidlay DT, McTaggart RA, Baird G, Shadi Yaghi, Morgan Hemendinger, et al. (2018) Accuracy of smartphone-based evaluation of emergent large vessel occlusion on CTA. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 171: 135-138.

- Thakar S, Rajagopal N, Mani S, Maya Shyam, Saritha Aryan, et al. (2018) Comparison of telemedicine with in-person care for follow-up after elective neurosurgery: Results of a cost-effectiveness analysis of 1200 patients using patient-perceived utility scores. Neurosurg Focus 44(5): E17.

- Reider-Demer M, Raja P, Martin N, Mariel Schwinger, Diana Babayan, et al. (2018) Prospective and retrospective study of videoconference telemedicine follow-up after elective neurosurgery: results of a pilot program. Neurosurg Rev 41(2): 497-501.

- Williams AM, Bhatti UF, Alam HB, Vahagn C Nikolian, et al. (2018) The role of telemedicine in postoperative care. Mhealth 4: 11.

- https://www.geek.com/tech/worlds-first-5g-powered-remote-brain-surgery-performed-in-china-1778982

- Akhtar M, Van Heukelom PG, Ahmed A, Rachel D Tranter, Erinn White, et al. (2018) Telemedicine physical examination utilizing a consumer device demonstrates poor concordance with in-person physical examination in emergency department patients with sore throat: a prospective blinded study. Telemed J E Health 24(10): 790-796.

- https://www.aan.com/siteassets/home-page/tools-and-resources/practicing-neurologist--administrators/telemedicine-and-remote-care/20-telemedicine-and-covid19-v103.pdf

- Buckland AJ, Miyamoto R, Patel RD, James Slover, Afshin E Razi, et al. (2017) Differentiating Hip Pathology From Lumbar Spine Pathology: Key Points of Evaluation and Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 25(2): e23-e34.

- Todd NV (2018) Quantifying the clinical aspects of the cauda equina syndrome - The Cauda Scale (TCS). Br J Neurosurg 32(3): 260-263.

- Zhao F, Li M, Tsien JZ (2015) Technology platforms for remote monitoring of vital signs in the new era of telemedicine. Expert Rev Med Devices 12(4): 411-429.

- https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-telehealth-coverage-policies

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.