Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Beliefs and Practices During Antenatal and Postnatal Period Among the Host Communities in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh

*Corresponding author: Md Khobair Hossain, International Center for Diarrhoeal Diseases Research, 68 Shaheed Tajuddin Ahmed Sarani, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh.

Received: August 01, 2020;Published: August 12, 2020

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2020.09.001451

Abstract

Bangladesh, one of the affected countries with refugee, faces the challenge to provide health care especially maternal care to the host communities. This paper presents maternal care related thoughts and practices in the host communities in Ukhia of Cox’s Bazar. We collected data using mixed method approach including a cross-sectional survey and semi-structure interviews. Using a probability sample, we selected mothers with infants (n=588) living in the host communities of Ukhia sub-district. We also conducted forty-two in-depth semi-structured interviews among the currently pregnant women who had also previously given births (n =21); and recently delivered women (n = 21). The survey found one quarter of the recently delivered women received at least four antenatal care visits and 28 percent women received at least one postnatal care visit. Seventy four percent of deliveries took place at home and 71 percent of the deliveries were assisted by untrained traditional birth attendants. The women mostly relied on their mother in law for information and support. Residents of the host community mainly use cheap, easily accessible informal sectors for seeking care. Cultural beliefs and practices also involved in this behavior, including home delivery without skilled assistance. There is demand of developing behavior change messages to change local resident’s attitude towards antenatal and postnatal care visits and encourage skilled attendance at delivery. Programs in the host communities should also consider interventions to improve social support for key influential persons in the community, particularly mother in law who serve as advisor and decision maker.

Keywords: Beliefs; Practices; Maternal Care; Refugee; Host Community

Introduction

Recently, Bangladesh has experienced rapid influx by Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMN) known as Rohingya [1]. Rohingyas were forcibly displaced from Myanmar and as of by 2019 about 742000 have cumulatively arrived Bangladesh [2]. Coupling with the previous influx, the recent displacement, has created the world’s most densely populated FDMN settlement in Cox’s Bazar with an estimated 911,566 Rohingyas currently living in different camps [3- 5] that affected the host communities severely. This rapid influx in Bangladesh, coupled with the increasing market price of goods, is likely to have profound implications on its health profile, especially on maternal and child health [6,7]. The perception and practices during pregnancy and child birth has strong link with maternal and child health that can affect the health of the child and mother after the birth. The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in Bangladesh was 214 per 100,000 live births in 2014 which decreased to 173 per 100, 000 live births in 2017 [8]. It shows that Bangladesh achieved major strides in MDG goal on Maternal and child mortality [9]. Nevertheless, data from the recent Bangladesh. Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2014 suggests that only 42% of the delivery were assisted by a skilled birth attendant, and that 37% of births took place at a health facility [10,11]. Comparing to the whole country condition the host communities is worse with respect to at least one antenatal care consisting of a medically trained provider (17% vs. 62%), all four antenatal care (0% vs 65%) and delivery at a facility (3% vs. 5%) [12]. In the same year, the neonatal mortality was 4% in Ukhia. Having this situation back in 2015, we hypothesize that after the influx the condition would be worse. This makes host communities health issues, especially of the pregnant women, a high priority. It is therefore crucial to address maternal health of the host community population in Bangladesh. In general the rural communities, are provided the maternal services at community clinics and Family Welfare Center (FWC) or in static service delivery sites operated by non-governmental organization (NGO) field workers. In some instances, services are available at clinics or dispensaries managed by NGOs, the government or the private sector [13]. But recent data showed that host population are having child birth at home most of the cases. There is lack of evidence about maternal care in the current FDMN influx at host communities. This paper investigates the beliefs and practices of different aspects of maternal care.

Materials and Methods

We used mixed method design in this study [14,15]. The quantitative and qualitative assessments were conducted separately in different time. In the quantitative assessment, we carried out a cross sectional survey the Ukhia sub-district of Cox’s Bazar between May and June 2019. We followed a two stage sampling each village contained 120 households. At first, ten villages from each union (local unit of a sub-district) were selected using probability proportional in terms of the village population size. Secondly, we selected around fourteen women from each village with an infant and currently living in the same village were randomly selected (n = 588). We used qualitative methods to explore perceptions, beliefs and practices around maternal care. Forty two in-depth interviews were conducted using semi-structured guideline in the selected areas between August and September 2019. Ukhia is a sub-district where a million refugee are inhabited with host communities. For the semi-structure interviews, we randomly enrolled 21 pregnant women having previous live births experience and 21 women who had a recent delivery and were not pregnant during the assessment. We took informed consent prior to complete the cross-sectional survey and qualitative interviews.

Data Collection and Analysis

In the cross sectional survey trained interviewers documented participant’s reproductive history, knowledge and perception about pregnancy, delivery, and post-partum care. We analyzed the survey data using Stata v 10. For the qualitative assessment, four well trained anthropologists conducted interviews using a semistructured interview guide. The interviews discovered community knowledge, perceptions and practices regarding maternal care. The interview guideline included modules on antenatal care related perceptions and practices, delivery, postnatal care, birth preparedness as well as the person’s influence on maternal care decisions. We reviewed the interview transcripts and developed a list of codes for the topics regarding the research questions. We applied the code manually to the transcripts [16]. We organized the coded texts in a matrix and translated into English pertaining the text.

Results

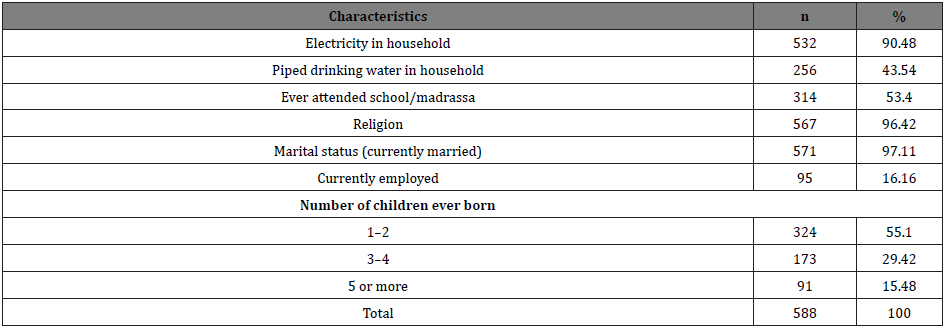

The Table 1 presents background characteristics of respondents documented in the cross-sectional survey. Eighty-two percent of the respondent’s bellow 20 years of age were married, having a median age of 17 years at marriage. The majority of the respondents (79%) were between 15 and 29 years. Most of the respondents had educational attainment either from formal or religious schools. Participants had widespread exposure to the electronic media such as the television; 94 percent of them reported that they watch television at least twice a week.

Prenatal Period

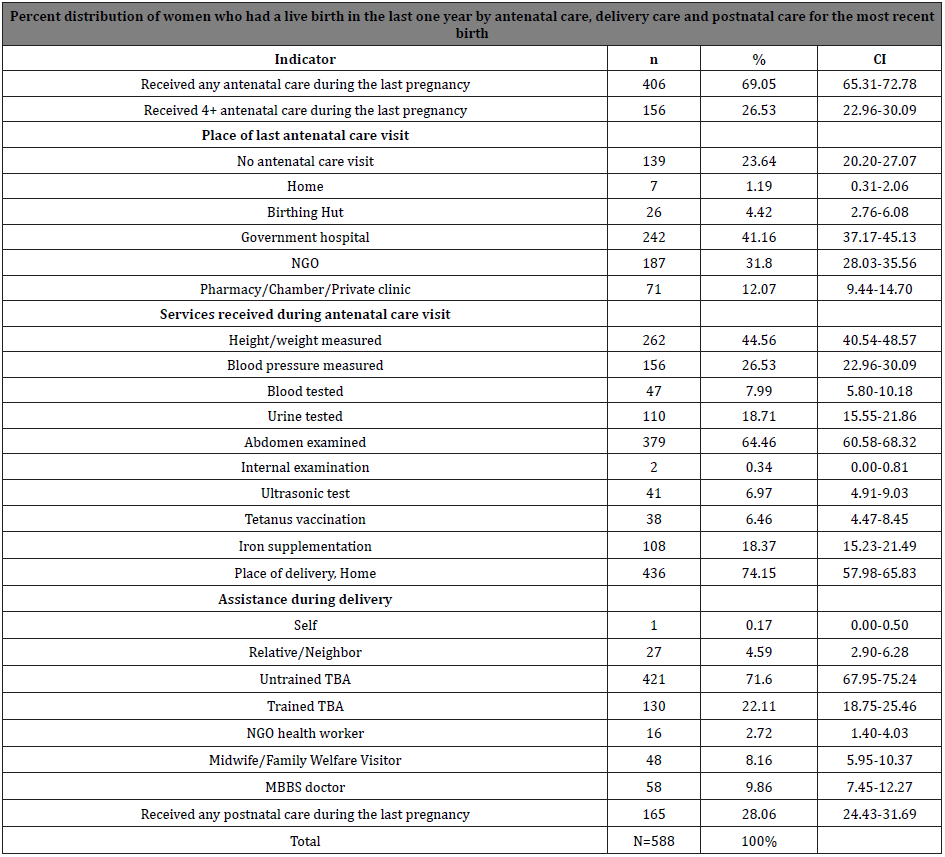

We found from the survey that three of every four women (69%) had received at least one antenatal care visit for the most recent birth while (27) percent of women reported as receiving four or more antenatal care visits (Table 2). The qualitative interviews explored that the nature of their antenatal care practice is about to check pregnancy either via urine test or physical examination. Some of the women reasoned that they emphasize reconfirmation of the pregnancy only rather than seeking antenatal care routinely. ‘Allah is always with poor people like us. He must help us; He will ease our work that are beyond our capacity’ (Pregnant woman, 23 years old). ‘I thought it would be normal so I had no plan; I knew that someone from my relatives would come for assistance

when I would the delivery pain. If required my family members would bring a ‘dai’ (Traditional birth attendant) for delivery’ (Recently delivered women, 25 years old). The majority of women reported as not having affordability to manage money in case of an emergency, reasoning that their parents would give money for pregnancy related need and delivery.

Delivery and Privacy

The survey revealed that 62 percent of women giving birth at home assisted by traditional birth attendants (TBA) (Table 2). In the in-depth interviews, women reported widespread preference for TBAs. TBAs were low-cost and women preferred to receive care in the home, unless there was a perceived complication. ‘Dai is easily available and comes at home for providing service. Also they are less expensive, and they live in our locality. A Dai is a female and my familiar person so I feel comfort to her than going to hospital for delivery’ (Recently delivered woman, 21 years old). Women prefer to give birth in their natal home, to ensure care and comfort from their family members. However, due to the distance and long travel, this was not often feasible. In that case, their relative from natal home come to accompany the pregnant woman. They ensure privacy for the delivering woman by sending the male and younger family members send outside the home typically. However, women reported that maintaining privacy was difficult after the delivery, as family members needed to return.

Table 2: Percent distribution of women having a live birth in the last one year by prenatal care, delivery care and postpartum care for the last delivery.

Postnatal Care

We conceptualized the postnatal care as if a women after the birth visits to a facility or any health worker comes to the house to check up on the woman and her newborn baby. The findings in the survey indicated that 28% of the women received postnatal care [17,18], while seven percent women attended four or more postnatal care. Qualitative interviews explored that after the birth, women are kept on the floor usually on a mat until the TBA cuts the umbilical cord and delivered the placenta. The TBA or close relatives such as mother in law or sister in law wash the woman, especially the lower part of the body. Usually, the TBA helped the woman for the day of delivery; then the family members or relatives assist the woman. A majority [19] out of 21 women having recent delivery reported not attending any postnatal care. As they did not perceive the condition as major health problem, they did not seek care. They did not think about the necessity of attending postnatal care even they suffer headaches and body aches. They perceived minor headaches and body aches as the normal parts of the delivery procedure.

Taboo during Post-Partum Period

Qualitative interviews revealed that women’s diets were inflexibily controlled after birth even during the pregnancy period. They did not allow a pregnant woman to eat bigger size fish as they thought the head of the baby would be bigger and it would be difficult for delivery. After the birth, they advised women to eat dry foods that was cooked without water and rice with mash potato and black cumin seed. They believe that these foods would keep the stomach of a woman cool and initiate the production of breast milk. Most of the women in the in-depth interviews opined not to eat hard food because after giving birth, the consumption of hard food makes the flesh inside flaccid and soft. Women reported that family members, primarily mother in law advocated for traditional practices with regard to food restrictions. “My mother in law always suggest the best ways in taking food especially after the delivery, this restriction at least will be beneficial for me” (A recently delivered woman, 20 years old, FGD-3).

All the women reported they knew that they should not go for heavy work for up to 45 days after delivery.

But in reality, this varied depending on support within the household and place of delivery. Many women

reported resuming work within 20 to 30 days after delivery.

Influential Group in the Family and Community

In the qualitative interviews, the mother in law emerged as an influential figure. Mother in law typically governs the behavioral practices of pregnant woman within the household. We also observed this influence in the extended families. During pregnancy, women have to rely on their mother in law during pregnancy practices and delivery-related decisions. At the community level, Traditional Healer (TH) had strong influence on treating pregnancy related complications providing amulets. Women believe that wearing amulets saves them from many illnesses and malicious spirits. “My mother in law introduced me to a local dai. She often come to me ask about my health condition and checked my belly. (Pregnant woman, 21 years old). Mother in law was perceived to be socially empowered while TH were traditionally respected in the community. Since THs had resided in the same community for long periods of time and had knowledge of reliable and available local medicines.

Discussion

This study combines both quantitative and qualitative methods to understand the maternal care practices to inform the programs covering maternal health of host communities. Our findings match the maternal practices and behaviors among the rural residents of Bangladesh [17-21]. Although there is increased availability of health services at community level in rural areas (Community Clinic, Family Welfare Center and Satellite clinic activities), women are less likely to attain those services [22]. Women in this study also maintained the practices and behaviors similar to those in the rural areas. This may be due to the fact that these women had been in restriction to visit outside and they share the access to local markets very less. As community supports, these behaviors and attitude have been profoundly embedded, and culturally accepted. These long practiced behaviors are difficult to change over the years. Studies reasoned that community people face cultural concerns as major barrier for seeking antenatal care in South Asia [23,24]. Women groups and community health workers (CHWs) play important role in motivating women in health care seeking. In South Asian cultural context, these groups often influence careseeking practices [25,26]. Other studies found that women are more likely to seek antenatal care when CHW pay at least one home visit during pregnancy [26]. Behavior change intervention should run for a certain duration with sharing consistent information to promote target behavior [27]. It is evident that training and supervision of CHWs are critical for planned implementation [28]. Thus, development skills among CHWs and train them can be a key strategy to create positive attitude about the routine care, promoting birth preparedness, and to improve the uptake of antenatal care and postnatal care visits. The key findings of this study point to the issues about the privacy and support during delivery. In the south Asia including Bangladesh, as the beliefs goes about pollution and impurity associated to the delivery process, family members isolate the mother and the child immediately after the delivery. They consider the mothers and the baby to be at vulnerable state after the delivery [29-31]. So they confine the mother and the baby believing that it will protect them from exposure to disease and evil spirits. Though the amount of seclusion and confinement varies across regions [32] the confinement period can last up to 45 days. This study found, women having desired privacy during delivery also as after the birth, but couldn’t enjoy support from natal home always. Findings indicated that social support is an important element for pregnancy and delivery. Study showed strong social networks for responding to social support but less effective economic assistance for pregnancy related health problems [33]. After the birth, generally female family members provide extensive support for mother and newborn during pregnancy and delivery in rural areas. We found that in Ukhia most of the women after marriage often live in nuclear families, at great distances from their family members. As a result women relied heavily on their neighbors for support. Neighbors often support in terms of helping women in childbirth, and postpartum period. Because of the distance sometimes they stayed at in laws house for delivery and mother in law provide great support. The programs on health education messages and behavior change could target these groups for intervention. This study has some limitations that need to be considered prior to interpretation of the findings. The findings were generated from the community practices on maternal care that may not reflect participant’s actual practices. However, as the qualitative and the quantitative data were analyzed, we can claim that the findings characterize the actual maternal care practice of the host communities. Our findings have some implications for the design of potential programs on maternal care in the host communities. Though there are similarity in maternal practices between host communities and rural households, this study found that women in host communities enjoy less social support. Generally, in the host communities traditional birth attendants and relatives assist during delivery. To enhance social support and maternal care for pregnant women, programs in host communities can train mother in law. Their training will include pregnancy, child deliver and postpartum periods.

Conclusion

This study emphasizes behavior change interventions to increase the antennal care and postnatal care visits. It also suggests to enhance community knowledge of birth preparedness, ensuring skilled maternal care and privacy at delivery. Programs in host community areas should also devise interventions to enhance support for women during this vulnerable period. In particular mother in law and husband who provide direct and social support can be trained on maternal care. These implications may contribute to improve maternal care practices in the host communities.

Acknowledgement

This study was developed and conducted with own support from Bhorer Alo Mohila Somaj Kollyan Sangstha. We would like to thank the community participants who spent time on providing valuable information to analyse. Then we would like to thank the co- researchers from, BRAC university and the Bhorer Alo Mohila Somaj Kollyan Sangstha. We specially thank the local leaders who helped to get access in to the community. We are also thankful to the mentors from icddr,b who provided support in preparing tools, analysis and write up.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Funding

This study was conducted with the Bhorer Alo Mohila Somaj Kollyan Sangstha’s own fund.

References

- Sarker M, Saha A, Matin M, Mehjabeen S, Tamim MA, et al. (2020) Effective maternal,Newborn and child health programming among Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh: Implementation challenges and potential solutions. PLoS ONE 15(5): e0234227.

- UNHCR, Asia Pacific. (2019). Rohingya emergency. Retrieved in July 2020.

- Lewa C (2009) North Arakan: an open prison for the Rohingya in Burma. Forced Migration Review 1(32): 11.

- Reliefweb (2019) Perspectives and priorities from guest and host communities in Cox’s Bazar. Retrieved in July 2020.

- World Vision (2019) Rohingya refugee crisis: Facts, FAQs, and how to help. Retrieved in July 2020.

- Action against hunger (2017) Rapid Market Assessment in Cox’s Bazar. Retrieved in July 2020.

- DanChurchAid (DCA) actalliance (2019) Market Assessment in Cox’s Bazar. Analysis for DCA’s Cash and Livelihood Project.

- Bangladesh Fertility Rater 1950-2020. Retrieved in June.

- Chowdhury S, Banu LA, Chowdhury TA, Rubayet S, Khatoon S, et al. (2011) Achieving Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 in Bangladesh. BJOG 118 (Suppl 2): 36-46.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) (2015). Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014: Key Indicators. Dhaka Bangladesh and Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) (2017). Bangladesh maternal mortality and health care survey (BMMS) 2016: Preliminary Report. Dhaka, Bangladesh and Chapel Hill NC USA.

- Health Bulletin. Ukhia Upazila Health Complex (UHC) (2016) Ministry of Health and Family Planning Welfare (MOHFW).

- Community Based Health Care (CBHC) (2019) Independent evaluation of community-based health services in Bangladesh. Dhaka: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Directorate General of Health 9 Services, Community Based Health Care programme and World Health Organization (WHO) Bangladesh.

- Ahsan KZ, Streatfield PK, Ahmed SM (2008) Community health solutions in Bangladesh: Baseline survey in Dhaka urban slums 2007. Scientific report no 104.

- Moran AC, Choudhury N, Zaman NU, Karar ZA, Wahed T, et al. (2009) Newborn care Practices among slum dwellers in Dhaka Bangladesh: a quantitative and qualitative exploratory Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 9: 54.

- Glynn LH, Hallgren KA, Houck JM, Moyers TB (2012) Free, Open-Source Software for the Sequential Coding of Behavioral Interactions. PLoS ONE 7(7): e39740.

- Morrison J, Osrin D, Shrestha B, Tumbahangphe KM, Tamang S, Shrestha D, Thapa S, Mesko N, Manandhar DS, Costello A (2008) How did formative research inform the development of a women’s Group intervention in rural Nepal? J Perinatol 2(Supp2): S14–S22.

- Simkhada B, Teijlingen ERv, Porter M, Simkhada P (2008) Factors affecting the utilization of Antenatal care in developing countries: systematic review of the literature J Adv Nurs 61(3): 244-260.

- Rahman A, Nisha MK, Begum T, Ahmed S, Alam N, et al. (2017) Trends, determinants and Inequities of 4+ ANC utilisation in Bangladesh. Journal of Health Population and Nutrition 36(1): 2.

- Md Shahjahan, Hasina Akhter Chowdhury, Jesmin Akter, Afsana Afroz, M Mizanur Rahman, et al. (2013) Factors associated with use of antenatal care services in a rural area of Bangladesh. South East Asia Journal of Public Health 2(2).

- Walton L M, Schbley B (2013) Cultural Barriers to Maternal Health Care in Rural Bangladesh. Online Journal of Health Ethics 9(1).

- Siddique AB, Perkins J, Mazumder T, Haider MR, Banik G, et al. (2018) Antenatal care in Rural Bangladesh: Gaps in adequate coverage and content. PLoS ONE 13(11): e0205149.

- Choudhury, N Moran, A C Alam, M A Alam (2012) Beliefs and practices during pregnancy and Childbirth in urban slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 12: 791.

- U Syed, N Khadka, A Khan, S Wall (2008) Care-seeking practices in South Asia: using formative Research to design program interventions to save newborn lives. Journal of Perinatology. 28(suppl 2): S9-S13.

- Bhutta ZA, Soofi S, Cousens S, Mohammad S, Memon ZA, et al. (2011) Improvement of perinatal and newborn care in rural Pakistan through community-based strategies: a clusterrandomised effectiveness trial Lancet 377(9763): 403-412.

- Wade A, Osrin D, Shrestha BP, Sen A, Morrison J, et al. (2006) Behaviour change in perinatal care practices among rural women exposed to a women's group intervention in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 6: 20.

- Hill Z, Taiwah Agyemang C, Manu A, Okyere E, Kirkwood BR (2010) Keeping newborns warm: Beliefs, practices and potential for behaviour change in rural Ghana. Trop Med and Intl Health 15(10): 1118-1124.

- Adams AM, Vuckovic M, Graul E, Rashid SF, Sarker M, et al. (2020) Supporting the role and enabling the Potential of community health workers in Bangladesh’s rural maternal and newborn health Programs: a qualitative study. Journal of Global Health Reports 4: e2020029.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Mitra and Associates, Macro International. BDHS (2009) Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007, Dhaka.

- Kavita Singh, Paul Brodish, Mahbub Elahi Chowdhury, Taposh Kumar Biswas, Eunsoo Timothy Kim, et al. (2017) Postnatal care for newborns in Bangladesh: The importance of health–related factors and location. J Glob Health 7(2): 020507.

- Choudhury N, Ahmed SM (2011) maternal care practices among the ultra-poor households in rural Bangladesh: a qualitative exploratory study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 11:15.

- Blanchet T (1984) Women, pollution and marginality: meanings and rituals of birth in rural Bangladesh. Dhaka: University Press.

- Joyce K, Edmonds, Moni Paul, Lynn M Sibley (2011) Type, Content, and Source of Social Support Perceived by Women during Pregnancy: Evidence from Matlab, Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr 29(2): 163-173.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.