Mini Review

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Fetal Cervical Teratomas: Etiology, diagnosis, and Treatment Options

*Corresponding author: Florian Recker, Departmen for Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital Bonn, Venusberg Campus 1, 53127 Bonn, Germany

Received: June 22, 2020; Published: July 20, 2020

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2020.09.001422

Introduction

Cervical teratomas are rare fetal tumors with a frequency of 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 40,000 live births, with a female-to-male ratio of 3:1 [1]. In a series of 1,253 teratomas of different types [2,3], only 6 (0.47%) were classified as epignathus [4]. Histologically, they are benign tumours formed by the three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm). While the majority of fetal teratomas manifest themselves in the coccyx region, cervical teratomas represent only about 6% of congenital teratomas. Moreover, there are some cases in the literature where cervical teratomas showed a malignant tendency. Thus Thurkow et al. [6] reported an extremely rare case of malignant teratoma of the neck, with mature and immature metastatic lesions in the lungs, in an immature fetus [5]. Further, Bauman and Nerlich reported a metastazing cervical teratoma of the fetus [6]. Additionally, there is another report of six malignant teratomas in the literature so far [7].

Ultrasound diagnosis

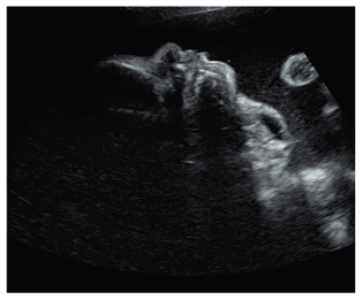

Ultrasound diagnosis has proved to be successful at very early stages of gestation. Thus between the 15-17 weeks an ultrasound detection can be achieved [8,9]. However, most of the lesions are seen in the late second and third trimesters, suggesting that the tumor can develop later in pregnancy [10]. The usonographic diagnostic clusters are based on the display of an anterior or bidirectional organoid facial mass that is partly solid and partly cystic (Figure 1). This mass protrudes (usually with no calcifications) from the fetal mouth and causes hyperextension of the head. Three-dimensional ultrasound can support the prenatal diagnosis [11]. Together with antenatal MRI, three-dimensional ultrasound may thus be of critical importance in identifying fetuses that require an ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure (Figure 1).

Prenatal treatment options

Cervical teratomas are rare congenital tumors with a poor prognosis and a nearly 100% mortality if not immediate managed and resected [12]. Teratoma occurring in the nasal cavity is a rare abnormality. When teratomas are found in the head or neck, high perinatal mortality occurs, mainly as the result of neonatal upper airway obstruction because the tumor impairs fetal swallowing and causes pharyngeal obstruction due to local mass effect. Thus, the main problems during pregnancy and the perinatal period are the increase in size, the resulting impairment of fetal swallowing with consecutive polyhydramnios and a significantly increased risk of preterm birth, and the difficulty of securing the airway postnatally [13,14].

For peripartal management, the decisive factor is whether there is compression of the upper airways. In these cases, delivery should be carried out by the so-called EXIT procedure (Ex Utero Intra Partum Treatment) in order to have sufficient time to secure the upper airways. This procedure, first described as a delivery method for fetuses with diaphragmatic hernia and iatrogenic tracheal occlusion [15], involves performing the dissection under general anaesthesia and high doses of inhalation anaesthetics for tocolysis. The edges of the uterotomy are secured with stacker systems to achieve the best possible hemostasis. After partial development of the fetus, the airways are secured at the placental perfusion. In collectives with fetal cervical teratomas, this part of the procedure takes 23 minutes [16,17] on average. The duration of placental support to the partially delivered fetus can even be as long as 60min [18]. A study reported the outcome of 23 EXIT procedures performed from 1996 to 2004 to deliver fetuses with giant masses in the neck. Three fetuses with giant cervical teratomas died of severe pulmonary hypoplasia. On postmortem, these patients presented severe airway distortion due to the mass. The carina was retracted superiorly to the first or second rib, resulting in compression of the lungs in the apices of the chest with pulmonary hypoplasia [19].

Disadvantages of the EXIT procedure are the risks of intubation anesthesia, increased maternal blood loss, and the increased risk of placental detachment, endometritis, and postpartum anemia [5]. A new alternative is fetoscopic endotracheal intubation (FETI) immediately prior to dissection, as described by Cruz Martinez et al [20]. This involves a fetoscopic endotracheal intubation (FETI) under local maternal anaesthesia. Using the Seldinger technique, an airlock is placed in the mouth of the fetus under ultrasound guidance and advanced through the fetoscope into the trachea. The free end of the endotracheal tube is placed in the amniotic cavity by slowly retracting the sheath and simultaneously advancing the sheath trocar under ultrasound control. Thus, the main disadvantages of the EXIT procedure can be eluded.

Conclusion

Cervical teratomas are rare, but usually benign congenital tumors with recognized multifactorial etiology. A prenatal ultrasound diagnosis can be made early in pregnancy (15-16 weeks) whereas 3D ultrasound and MRI may enhance the accuracy of the antenatal diagnosis and may aid in the selection of patients requiring treatment. The delivery of a fetus with a cervical teratoma should involve elective cesarean section with the EXIT or FETI procedure with a resection of the tumor mass afterwards.

References

- Calderon S, Kaplan I, Gornish M (1991) Epignathus. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 20(6): 322-324.

- Grosfeld JL, Ballantine TV, Lowe D, Baehner RL (1976) Benign and malignant teratomas in children: analysis of 85 patients. Surgery 80(3): 297-305.

- Tapper D, Lack EE (1983) Teratomas in Infancy and Childhood: A 54-Year Experience at the Children's Hospital Medical Center. Ann Surg 198(3): 398.

- Sarioglu N, Wegner RD, Gasiorek-WA, Entezami M, Schmock J, et al. (2003) Epignathus: always a simple teratoma? Report of an exceptional case with two additional fetiforme bodies: Epignathus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 21(4): 397-403.

- Thurkow AL, Visser GHA, Oosterhuis JW, de Vries JA (1983) Ultrasound observations of a malignant cervical teratoma of the fetus in a case of polyhydramnios: case history and review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 14(6): 375-384.

- Baumann FR, Nerlich A (1993) Metastasizing cervical teratoma of the fetus. Pediatr Pathol 13(1): 21-27.

- Shoenfeld A, Ovadia J, Edelstein T, Liban E (1982) Malignant cervical teratoma of the fetus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 61(1): 7-12.

- Gull I, Wolman I, Har-Toov J, Amster R, Schreiber L, et al. (1999) Antenatal sonographic diagnosis of epignathus at 15 weeks of pregnancy: Epignathus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 13(4): 271-273.

- Clement K, Chamberlain P, Boyd P, Molyneux A (2001) Prenatal diagnosis of an epignathus: a case report and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 18(2): 178-181.

- Daskalakis G, Efthimiou T, Pilalis A, Papadopoulos D, Anastasakis E, et al. (2007) Prenatal diagnosis and management of fetal pharyngeal teratoma: A case report and review of the literature. J Clin Ultrasound. 35(3): 159-163.

- Ruano R, Benachi A, Aubry M-C, Parat S, Dommergues M, et al. (2005) The impact of 3-dimensional ultrasonography on perinatal management of a large epignathus teratoma without ex utero intrapartum treatment. J Pediatr Surg 40(11): e31-34.

- Goldstein I, Drugan A (2005) Congenital cervical teratoma, associated with agenesis of corpus callosum and a subarachnoid cyst. Prenat Diagn 25(6): 439-441.

- Faschingbauer F, Geipel A, Berg C (2007) Fetale und Plazentare Tumore. Walter de Gruyter 273-300.

- Kamil D, Tepelmann J, Berg C, Heep A, Axt-Fliedner R, et al. (2008) Spectrum and outcome of prenatally diagnosed fetal tumors. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 31(3): 296-302.

- Mychaliska GB, Bealer JF, Graf JL, Rosen MA, Adzick NS, et al. (1997) Operating on placental support: The ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure. J Pediatr Surg 32(2): 227-231.

- Laje P, Johnson MP, Howell LJ, Bebbington MW, Hedrick HL, et al. (2012) Ex utero intrapartum treatment in the management of giant cervical teratomas. J Pediatr Surg. 47(6): 1208-1216.

- Lazar DA, Olutoye OO, Moise KJ, Ivey RT, Johnson A, et al. (2011) Ex-utero intrapartum treatment procedure for giant neck masses-fetal and maternal outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 46(5): 817-822.

- Cardesa-Salzmann TM, Mora-Graupera J, Claret G, Agut T (2004) Congenital cervical neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 43(7): 785-787.

- Liechty KW, Hedrick HL, Hubbard AM, Johnson MP, Wilson RD, et al. (2006) Severe pulmonary hypoplasia associated with giant cervical teratomas. J Pediatr Surg 41(1): 2230-2333.

- Cruz-MR, Moreno-AO, Garcia M, Pineda H, Cruz MA (2015) Fetal Endoscopic Tracheal Intubation: A New Fetoscopic Procedure to Ensure Extrauterine Tracheal Permeability in a Case with Congenital Cervical Teratoma. Fetal Diagn Ther 38(2): 154-158.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.