Review Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Post-Trauma Early Intervention

*Corresponding author: Hana Válková, Faculty of Sport Studies, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic, Czechia

Received: May 16, 2019; Published: June 21, 2019

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.03.000688

Abstract

The term of early intervention is usually associated with early childhood. But early intervention is an important process after injury in teenagers or early adulthood. Research reports indicate that it requires a period of two years to restore the habits of everyday life. The background of the presented research study is based on the theoretical models of post-trauma development and modification of the theory of transition. Physical activities can play a significant role as the one of the determinants of a post-trauma early intervention, which should shorten the recovery period. The theories are confronted with the research findings of sitting volleyball players of Bosnia & Herzegovina and sledge-hockey players of the Czech Republic. The determinants of social environment, health and rehabilitation care, economy and technologies, as well as the origin of the trauma (injury) were found in both countries but in different proportions. The period of one year is usually important for daily life acceptance, and a second year for participation in regular Paralympic sports.

Keywords: Theory of transition, Family surrounding, Sport for disabled, Sitting volleyball

Introduction

Understanding the theory of transition

Motto:

a. You cannot teach an old dog new tricks

b. Young Learner - Wise Elder

c. What you learn in your youth will be useful when you are old

The attention given to the childhood years is at the centre of developmental psychologists’ theories because early childhood and early intervention are documented as a very important and sensitive period for the future functioning of every individual. This approach is stressed in the education of parents, teachers, and sports coaches from the point of view either for the general development of the personality or for high performance due to talent cultivation. Piaget´s Theory of Cognitive Development and Ericsson´s Theory of Psychosocial Development respect the approach based on the necessity of early intervention [1], which can be summarized as follows:

i. Trust stage: birth up to 2 years - learns about the physical environment, routine operations;

ii. Autonomy stage: 2-4 years, recognizes the existence of free will and choice;

iii. Experiences the imitation stage: 4-6 years, imitation roles, models the world around them;

iv. Competence stage: 6-12 years, they are able to demonstrate competence in front of their peers;

v. Identity phase: 12-18 years, marks a critical time of development between childhood and adulthood.

These educational approaches should be accepted during “talent development” and life-span career development. Bloom reported in his theory about the talent development of athletes, as well as concert pianists, sculptors, mathematicians, etc. He believed that there were three career phases: initiation, development, and perfection. He completed his model with the roles and specific support of educators: performers, mentors, and parents [2,3]

Côté, Baker and Abernethy [4] summarized the discussion with dividing “training” into deliberate play and deliberate practice; and they used new terminology for the stages of development: sampling years, specializing years, and investment years. Sampling years (with an accent on deliberate play) are important from the point of view “intrinsic motivation”. The role of parents has been reported as a very important marker during all stages of sports career development. Parents play an important role, particularly in the early intervention period, in the first years of professionalism, this means in the early stages of participating in sports (new experiences, providing a positive environment and attention to children interests, but not strongly stressing the child or searching for achievements). One of the crucial questions was: how many hours is it necessary to spend in exercise before reaching the top of your performance? In addition, how much time is available for youths or adults?

The recent official title of the “Theory of Transition” has its origin from the last century and was presented by Czech authors, Vaněk & Hošek in 1975 [5]. The concept from the 1970s was explained as the developmental phases of motivation during a sports career. Their theory was founded on three sources: a) Madson’s theory (1969), b) the theory of “Ustanovka” (Puni, 1961, Uznadze 1966, in Vaněk & Hošek, [5]) as the potential of activity and regulation, and c) Atkinson’s theory of the “need for achievement” (1966). The authors stressed a developmental approach. The terminology of the four developmental phases was presented at the FEPSAC conference [5], as generalization; differentiation; stabilization; involution. During the next several years they changed the terminology to primary (spontaneous) expansion, equal “early intervention for a sports career”; selective self-inclusion; stabilization; involution.

A more detailed explanation respected the age, level of performance, type of motivation, and the role of the social environment of parents, teachers, coaches, and peers. Variables of the social environment seemed to be crucial and were mainly the person’s family.

1st Stage - primary expansion (early intervention)

Age up to10 years

Activities spectrum all-round, majority of deliberate play

Performance low, beginners discovering the potential of activity

Motivation primary, based on need for motion, affiliation, fun and joy

Function of educator early sports socialization, attitudes towards physical activity, basic principles of skills

2nd Stage - selective self-inclusion

Age youth/adolescent

Activities spectrum sports specialization, deliberate practice, training

Performance middle (1st selection)

Motivation primary mixed with secondary (expectation of awards, advantages)

Function of educator “Lucky with coach“

Stage 3rd - stabilization

Age adults

Activities spectrum specialization

Performance high/super

Motivation secondary, linked with external markers, economy and media attention

Function of educator maintaining on top level position, team building

4th Stage - involution

Age higher adulthood

Activities spectrum specialization

Performance mature

Motivation primary, linked with joy

Function of educator team harmonization, phenomenon of ambassadorship behaviour as a model for children, teenagers

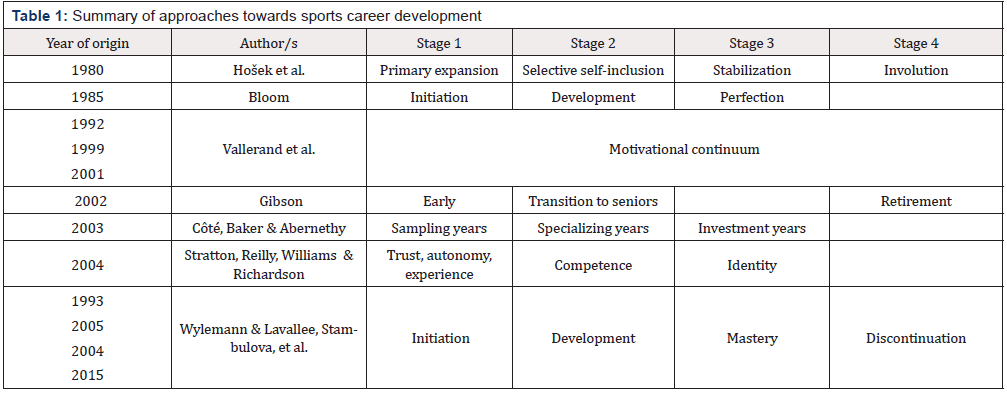

Wylleman and others [6-10] worked on the topic “career development” since the 1990s up to the present time. The presented terminology “transition period” (originally from Ericsson) was used firstly for the period between the top sportsmen performance stage and his/her sports retirement stage. Recently, the “Transition Theory” has been applied and accepted in respect of any periods/ stages of sports career development (Table 1).

According to these ideas, can this model be applied to other situations, for example, in situations where a career is interrupted after serious injury, specifically in relation to Stage 1, which is oriented on early intervention? Is it possible to apply the “Theory of Transition model” within this situation? Is it possible to apply crucial questions formulated within the general model: how many hours? how much time is needed to settle personal issues and later to participate in physical activity? Is it possible to define some markers for motivation and adherence in sports activities? The issues became the basis for the students´ projects, which are summarized in the presented article.

Sport as an Agent of Socialization

Motto:

a. Tempora, o mores

b. Birds of a feather flock together

c. Like will to like.

Both recreation physical activities and competitive sports might be opportunities that fulfil the criteria for successful integration in sports and via sports to society. Disability sports might include sports that were designed for selected disability groups: sitting volleyball for amputees, goal-ball for the blind, wheelchair basketball for paraplegics, unified bocce for Special Olympians, etc. [11].

Sports are realized in a social environment, which encompass the immediate physical surroundings, social relationships, and cultural milieus within defined groups where people interact, cooperate, and compete [12]. Components of the social environment include the built infrastructure, industrial and occupational structure, labour markets, social and economic processes, wealth, social and health services, power relations, governmental policy, race and ethnic relations, religious institutions, social equality or inequality, cultural practices, the arts, beliefs about place and community. The social environment subsumes many aspects of the physical environment, given that contemporary landscapes, water resources, and other natural resources have been at least partially configured by human social processes [12]. Sports are realized in outdoor and indoor social environments, thus, sports in the social environment can improve social skills, not only for participants, but also for daily life, for example, in teamwork, harmony between cooperation and competition, self-discipline, respect for others or leadership, to take appropriate risks, and to learn how to manage failure and success in a safe and supportive environment [13]. Even inclusion in spontaneous groups (family) or in chosen social groups is linked to the need for affiliation and necessary improvement of intrinsic self-motivation, too.

Motivation for sports participation

Motto:

a. Where there is will there is way

b. A faint heart never won a fair lady

c. If someone does not want, it is worse than when you can not

Motivation is considered as one of the most important issues for any achievement in daily life, as well as in sports. Ogilvie and Tutko [14] considered motivation for sports participation as a complex situation, which consists of social approval, a need for love, or a need for achievement, status, and security. This concerns both the general population, as well as the population with disabilities [15]. Among many theories, two theories are the most popular and accepted for the physical activities context and sports setting, these are: a) “task orientation” – focusing on improving the quality of skills, performance, achievement and goals, and b) “ego (outcome) orientation” – focusing on being persistent, with constant comparison with others [16]. According to Brasile and Hedrick [17], motivation for participation, involvement and further adherence in sport activities can be grouped into three major categories: task, ego and social incentives. Duda and White [18] examined goal orientation and perceived reasons for sport success among adolescents with physical disabilities. The results indicated that both task and ego-oriented goal perspectives were present among athletes with disabilities. Similar findings were included in the research study of Brasile and Hedrick [17].

Five major external issues connected with sport participation, which were identified as important for people with disabilities, were formulated by Collins and Kay [12], these include: transport, physical and human barriers to access, staff training and programming, and information and communication. All the authors above showed similar motivation clusters. The markers mentioned above influence the development of the motivation trajectory: the length of some transition stages, the intensity of intrinsic - extrinsic motivation, variables of incentives to participate in sport and the power of adherence, as well as competitive sports orientation. Some people engaged in sport for health reasons, to improve their physical fitness or discover their physical skills or to revive ignored abilities or learn about different games and sports. Others may seek an opportunity to meet new people, make friends, or to have fun, while some of them have the desire of wining a Paralympic medal as the ultimate prize [3].

As we found out from the work of Kälbli [19], most of the Hungarian sitting volleyball players (2nd stage of transition) did sports as a hobby, for fun or just to keep healthy. But no differences were found between the general population and individuals with a disability: both groups on a recreation level and competitive level. The differences between male and female elite athletes with a spinal cord injury were presented by Fung [15]. Their prior motivation for sport participation was fitness and skills development, the need for movement and energy release and, later, top achievement, winning medals, and glory, which can be considered as typical in the development of the motivation stages, according to the transition theory.

Wu and Williams [20] assessed the motivation of sports participants with a spinal cord injury. They stressed the importance of early intervention in the hospital just after the accident (physical, psycho-social and rapid flow information), appropriate timing and the quality of the hospital rehabilitation program, information from therapists, visits from disability sports clubs’ members, and re-introducing physical activities and sport. These markers can be classified as an important part of early intervention in the first stage of transition. The person concerns him/her-selves in a new situation after the traumatic event, feels the problems of the post-trauma situation, finds him/her-selves in an unexpected life situation. He/she needs to start just at the beginning of another new life trajectory.

Post-trauma situation

Motto:

a. Per aspera ad astra

b. Every cloud has a silver lining.

c. No gain without pain.

The background of the transition theory is a biodromal approach that is the perception of the life span throughout the continuum of life´s crossroads. The crossroad is usually a traumatic event, which affects the further development of the individual and his/her surroundings; these events can evoke a personal feeling of happiness, as well as trauma, which alternate in the course of life. Different types of reactions, behaviour and inner experiences accompany the traumatic event. The question is whether a trauma, which usually causes shock, can later evoke either post-traumatic syndrome or reinforce a new quality of life. What are the variables which can influence either the beginning of a decline or an improvement in life’s trajectories? Examples might be the fiction of writers like Dostoevsky or Solzhenitsyn, who reported positive changes after overcoming dramatically difficult situations [21]. Similarly, Hošek formulated well-being as personal satisfaction and comfort after overcoming discomfort; wellness with coping with illness [22].

The phenomenon of post-traumatic syndrome has been investigated since World War 1 and more intensively after World War 2 [23-25]. Although war is one of the most stressful experiences, other personal negative experiences can also lead to long-term stress. The sources of all negative events are based on a loss of security, safety and self-awareness. The concepts of stress have been explained with many theories but just three of them are common for the understanding of the post-traumatic situation:

a) Stress as a physiology reaction of the organism, the theory of Selye (1956);

b) Stress as the stimulus for re-adaptation. It is possible to classify the stimuli (life-events) according the criteria of difficulty and potential strategy of coping: loosing a child, loosing a partner, divorce, values and freedom, natural disasters, health, poverty, emigration, loosing a job, retirement, etc. [26]; c) Stress as a transaction stimulus for cognitive evaluation and emotional processing leading to the perception of a challenge [27].

Currently, the coping stress strategies are investigated in relation to pre– or post surgery intervention, the situation in families with a disabled child, after a transport crash or sports injuries, as the prolonged post-traumatic syndrome dramatically affects the health status of the individual affected and his/her surroundings [28].

Post-traumatic development has been characterized in continuous stages [21]:

Denial: “This can’t be happening to me.”

Anger: “Why is this happening? Who is to blame?”

Bargaining: “Make this not happen, and in return I will ____.”

Depression: “I’m too sad to do anything.”

Acceptance: “I’m at peace with what happened.”

An important issue for the quality of life for the person concerned is whether the traumatic event will either result in posttraumatic syndrome or in a stress coping strategy. The length of time individuals remain in the post-traumatic stages, the length of inclusion in major society (?) and the final solution depends on a variety of factors [28]. The personal features of the person before the trauma are the most important. In biodromal perspectives, the person’s education, formative years and generation transition in the early intervention period are the background of the personal features, which Antonovsky indicated as a “personal sense of coherence”, consisting of an understanding of reality, the acceptance of the situation as a challenge, an active approach to the future, and the ability to invest energy for the future [23]. Other variables include the: timing of the event, age of the individuals, origin of trauma, level of social support, and the demographic, socio-economic or cultural context [21].

Research Overview

The original purpose of disability sports came from the pioneering approach of Sir Guttmann, who viewed physical activities as a part of rehabilitation including social rehabilitation [11]. Physical activities and sports formed a link between rehabilitation or education, on the one hand and leisure on the other, later, even the fulfilment of the aspirations to achieve the best performances at the top competitive level [29]. As physical activities and sports are considered to be part of the phenomenon of a process of socialization, we should go back to the issues mentioned in the introductory part:

i. How much time is needed for the transition back into mainstream society?

ii. Is it possible to apply the model of the theory of transition after a trauma situation?

iii. What markers can be common or important for the motivation to start again with physical activities or sports?

iv. Which similarities or differences could be formulated by comparing the classical process of early intervention and early intervention of adults after an accident?

v. Can we find similarities – differences related to early intervention after type of trauma in selected countries?

The effort to resolve these issues resulted in the composition of an internal research project with the participation of 4 students: two Czech students, one from Bosnia & Hercegovina, one from B&H, Republica Srpska. The leader of the project and theses mentor was the author of this article. Summary of theses included in the project is.

Methods

Participants included in the data collection period

An internal research project, involving several universities, was oriented on early intervention after trauma of persons with physical disabilities. Due to the current situation, the students from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Republica Srpska had an opportunity to study in the Czech Republic within a project supporting an international students exchange, which was a unique possibility for student cooperation. The comparison of variables from those countries seemed to be suitable as the project anticipated different social backgrounds in those countries. Extracts from four students theses were used for this article. The participants were sportsmen after injury, who had been recruited from team sports because the project wanted to stress a more intensive social environment. In reality, sledge hockey and wheelchair basketball players in the Czech Republic and sitting volleyball in Bosnia were included. It was the reason why only males were involved in the project. The basic diagnoses of the athletes were amputation and paraplegia. Data regarding the demographic background, personal history and sports history of the participants was obtained by semi-structured interviews (ethical consensus was provided). The topics of the semi-structured interviews were oriented on the “life before”, the “life after” the trauma, the most positive or supportive experience, and the most negative or stressful experience.

Data evaluation

The data was processed by logical analyses using a nominal categorical scale. Nominal categories emerged from the semistructured interviews. The guidelines for formulating the categories of motivation for the adherence of the sitting volleyball players were from studies of Vute [3] and Collins and Kay [12]. Vute analysed the responses of male and female sitting volleyball players at the competitive top level, as well as beginners. His categories were: the way to success, healthy status, fun and joy in sport, friends and socialization, spare time, personal strength and power, sporting life-style, psycho-physical ability, ambitions, medialization. Differences between males and females were found. The motivation of the top male players was more ego oriented than that of females. In addition, differences related to the length of sports careers were also found. Beginners preferred to have fun in sport, to make friends and socialize, fill their spare time and relax. Collins and Kay [12] presented general variables, which prevented participation in sports after injury: transport accessibility, physical and human barriers to access, staff training and programming, information and communication. Even these authors were oriented on the motivation of engagement and adherence in sports of persons with disabilities; they were not interested in the length of the period between the trauma and the decision to start sport. The checklist of the nominal categories, which resulted from four studies, was: the family unit, friends “before”, new friends “after”, and the economic and technological situation.

Results

Study 1 – Czech Republic [30]

Eight male case studies who had sustained injuries in either transport accidents, sports injuries, or work injuries and were paraplegic or had lower limb amputations. All of them had suffered an injury after 18 years of age and their age, at the time of questioning, was between 28 – 43 years. Recently, they had played sledge-hockey, wheelchair basketball, or quad rugby. Their accommodation for sports inclusion lasted from 1 year and 5 months up to 3 years, and in one extraordinary case, 14 years (the trajectory of the life-span had gone since a period of suicidal attempts, using alcohol, later orientation on sport up to recent period in happy family. Usually, they started with various recreation activities, as they did not receive adequate information about sports opportunities, which they perceived as the most problematic issue. The technology barriers and a lack of sports equipment were also stressful for them, as was loosing old friends, as they could not absorb the new situation. They experienced further economic problems with the need to adapt their accommodation and the absence of a car. The most important domain to them was family support and new friends from the disability sports environment.

Study 2 – Czech Republic [31]

Nine male case studies who had been injured in transport accidents, or sports (skiing, jumping in water) who were paraplegic or had lower limb amputations. All of them had suffered with injury after age 16 years and their age at the time of questioning was between 23 – 26 years. Recently, they had played sledge-hockey, wheelchair basketball; one of them had done athletics throwing, and two of them had done mono skiing. Their accommodation for sports involvement lasted from 1 year and 8 months up to 3 years. They considered that family psychosocial support was the most important criterion for starting an active life style. The next positive issue was the stay in a rehabilitation centre as they could receive information about sport and meet new friends with sports experience and even Paralympic experience. However, they had lost their old friends from their previous life before injury. Returning to the original majority (contact with “old friends” and the perception of society and self-perception was difficult. Their new economic situation or the absence of a car was not thought too stressful as they could handle a car again after one year.

Study 3 – Bosnia and Herzegovina [32]

Sixty-seven male participants after injury, with paraplegia or leg amputations were questioned during an international tournament in sitting volleyball (in Banja Luca). Their age was from 20 years up to 60 years (the sitting volleyball coaches with disabilities were also questioned). They participated in competitive sitting volleyball after two or more years and their motives for playing sitting volleyball were “to find friends in society” after the trauma. The first period after the trauma was perceived as a crucial point for their life’s development, not only for sports participation. Even though they started with basic general activities, sitting volleyball was a previous sport for the disabled in Bosnia at that time. Their first motives were for socialization, to find friends, and join in various physical activities. Later, task oriented motivation led to regular training and competitive goals up to performing in international tournaments.

Study 4 - Bosnia and Herzegovina [33]

Nine male case studies: were male who had been injured mostly in war accidents from the effects of gunshot wounds, shrapnel grenades, and landmines. All of them had suffered with injury after the age of 18 years and their age at the time of questioning was between 26 – 52 years, with an average age of 37.7 years. All of them started with sitting volleyball very early after injury, mainly in the clubs in Sarajevo and Tuzla. The team questioned was the national Bosnian team, which was the winning team in the Paralympics sitting volleyball in London, 2012. Their adaptation for participation in physical activities lasted from 6 months to 10 years after the traumatic event; most frequently it was 28 months in regular training, and participation in competitive sitting volleyball after 2 years and 6 months. They marked the order of determinants for participation in sports after the war trauma as follows: a) surrounding family, b) old friends, c) new friends from sport (who had usually suffered a similar fate). Their stay in hospital and the rehabilitation centre was the most stressful for them due to war or the fresh period after the war; it was the economic, technological and emotional situation. Getting a car was also considered important because there were problems with any kind of public transport.

Discussion

We compared the type of team sports in two countries mentioned above - the sledge-hockey and wheelchair basketball, which were sports played previously in the Czech Republic, and sitting volleyball, which was played in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The reasons may be associated with the sporting traditions in each country, but also with the technical and economic possibilities and requests at that time. Because sledge-hockey and wheelchair basketball need a more demanding playground and equipment, it is not easy to manage this sport. Sitting volleyball seems to be a favourable choice for athletes with lower limb amputations. Both sitting and standing volleyball can be modified for athletes with different physical disabilities, age, and gender, with the different skills of beginners or those more advanced [34]. These indicators are available for the first period of motivational development (the first stage of transition) and the comprehensive training for the top Paralympics competitions (third stage of transition). Traditionally, standing volleyball, as well as sitting volleyball, became attractive in the former Yugoslavian countries. Due to the attractiveness of the sport and its easier management than the wheelchair basketball teams from Bosnia, it has played an important role in the development of sitting volleyball in history [35].

The differences have been found in legislation, which influence possibilities for sports inclusion and the selection of types of sports. The governmental authority in the Czech Republic accepted the European legislation concerning the rights of individuals with disabilities in 1993 and the follow-up Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Participation in Cultural life, Recreation, Leisure and Sport in 2009 (UNO: CRPD, Article 30). Bosnia and Herzegovina ratified the UNO Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in March 2010. Previously, it had ratified the Standard Rules on the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities (CDDS, 1987) [36]. Currently, Bosnia has developed and adopted a policy on disability, according this governmental body, which should create action plans at the local level.

The external indicators, for example, legislation, technologies, equipment, and economic level can influence the selection of possible sports. Participants of Study 1 perceived a problem with technique and equipment; the level of technological background was very stressful. Three years later (Study 2), it was not so stressful due to some progress having been made.

An interesting finding was the phenomenon of “loosing old friends from their previous life” and problematic self-perception in contact with “former old majority” in society living in peaceful situation with a quite good economy (CR), compared to the society in conflict. “Old former friends” probably created a more cohesive surrounding with family members. Can we deduce that all of them lived in traumatic situations in which it was necessary to support each other? Or is the question only speculation?

In spite of the differences among the presented studies, participants from all four studies stressed the necessity of early information (which can be deduced like early intervention). But the number one indicator was “psycho-social support from surrounding family” which was crucial for coping with trauma strategies, as well as for starting, adhering to and development of future sports. Family intervention is linked with the length of the first stage of the transition and future adherence of the selected sport, which was, in general, from 6 months up to 3 years (on average 1 year and 8 months.)

Although studies of coping with stress underline the physiology concept [37] or re-adaptation according to the classified psychophysiology loading [26] within the sports orientation domain, we can understand stress as a transaction, or a stimulus for the perception of a challenge [27]. Early information about physical activities and sports participation after a traumatic event was also formulated by the interviewed participants as very useful, either from their family surrounding them or from the hospital/rehabilitation staff. This means that family members and rehabilitation staff should be informed on how to provide adequate information. Sports clubs should play relevant roles as well, specially, in the first stage of transition [38-43].

Conclusion

The four studies described the documents regarding the possibility of applying the classical theory of sports transition to the environment of physical activities and sports for disabled persons after a traumatic event. The possibility can be considered as a recommendation of how to arrange faster and easier management in daily life as well as for sports socialization in practice.

Stage 1 – early intervention in the classical model is oriented on children and preschoolers. Parents are crucial in the early states of intervention (first stage in the model of transition). In an environment of disabled sports, the age of the disabled is postponed in adolescent age and again family support is important. In this we can see similarities in the child’s development and the development of adolescents after a traumatic event. Motivation cannot be associated with only the “task-goal” orientation or “ego” orientation. This motivation can come later for those interested in high level competitive sports. Again, there is a parallel development in mainstream sport on the recreation level as well as in disabled sport. But coping with the post-traumatic situation of adolescents and their inclusion into society via sport is due to respecting early intervention, which is the most important issue.

References

- Ericsson KA (2003) Expert performance in sports: advances in research on sport expertise. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, ICL.

- Bloom B S (1985) Developing talent in the young. Ballantine, New York, USA, p. 1-5.

- Válková H (2007) Life Span Sports career motivation-development: phases of Transition. FEPSAC Proceedings 2007, Chalkidiki Vute R (2004), Studies on volleyball for the disabled World Organization Volleyball for Disabled, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

- Côté J, Baker J, Abernethy B (2003) A developmental framework for acquisition of expertise in team sports. In: JL Starkes, KA Ericsson (Eds.), Expert performance in sports. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, ICL

- Hošek V, Vaněk M (1975) Úspěch jako motivační factor při sportovní činnosti. [Success as the factor of motivation during sports activities.] In: Psychologie a sport. [Psychology and sport.] Proceedings of sport psychologist, FEPSAC. Praha: Olympia, pp. 76-93

- Lavallee D, Wylleman P (2000) Career transition in sport: International perspectives. WV: FIT, Morgantown.

- Stambulova NB, Ryba TV (2013) Athletes´ careers across cultures. London and New York: Routlege, Taylor & Francis Group, USA.

- Stambulova NB, Wylleman P (2014) Athletes´ career development and transitions. In G Papaioannou, D Hackfort (Eds.), Routlege companion to sport and exercise psychology. Global perspectives and fundamental concepts. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group UNO (2009). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities : Participation in cultural life, recreation, leisure and sports. Article 30 UNO, New York, USA, pp. 605-620.

- Wylleman P (2005) The career development of elite athletes: a sport psychological perspective. In: Proceedings of 4th International Scientific Conference on Kinesiology. Opatija, Croatia.

- Wylleman P (1993) Career termination and social integration among elite athletes. In S Serpa et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the VIII World Congress of Sport Psychology. International Society of Sport Psychology, Lisbon, Portugal.

- De Paw KP, Gavron SJ (2005) Disability Sport (2nd edn). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, ICL.

- Collins MF, Kay T (2003) Sport and social exclusion. Routlege: Francis Taylor, England.

- Sherrill C (1998) Adapted Physical Activity, Recreation and Sport. Cross disciplinary and Lifespan, The Mc Graw -Hill Companies, Dubuque, USA.

- Ogilvie B, Tutko T (1963) A psychologists review the future of motivation research in track and field. Track & Field News, US.

- Fung L (1992) Participation motives in competitive sports: A crosscultural comparison. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 9(2): 114-122.

- Skordilis EK, Koutsouki D, Asonitou K, Evans E, Jensen B et al. (2001) Sport orientation and goal perspectives of wheelchair athletes. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 18: 304-315.

- Brasile FM, Hedrick BN (2001) A comparison of participation incentives between adult and youth wheelchair basketball players. Palaestra, Greece, 7(4): 40-46.

- Duda LJ, White SA (1993) Dimensions of goals and beliefs among adolescents with physical disabilities. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 10: 125-136.

- Kälbli K (2008) Injury and sport specific training for sportsman with disability sitting volleyball players. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, pp. 1-19.

- Wu SK, Williams T (2001) Factors influencing sport participation among athletes with spinal cord injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33(2): 177-182.

- Mareš J (2012) Post-traumatický rozvoj člověka. Praha: Grada Publishing, Czechia.

- Hošek V (2010) Wellness, well-being a pohybová aktivita. In: V Hošek, P Tilinger (Eds.), Wellness jako odbornost, pp. 7-14. Praha, Palestra: Tiskcyklos, Czechia.

- Antonovsky A (1987) Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well.: Jossey Bass. In: J Mareš (2012) Posttraumatický rozvoj člověka, Praha Grada Publishing, Czechia, p. 14.

- Antonovsky A (1985) Health, stress, and coping. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, California

- Frankl, Check Name VE, (2006) Vůle ke smyslu. Praha, Cesta.

- Holmes T, Rahe R (1967) Readjusting rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 12: 213-233.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, coping. New York: Springer Press, USA.

- Kořán M (1986) Dynamika procesu vyrovnávání se s náhlými změnami zdravotního stavu. Praha: Bohnice: Výzkumný ústav psychiatrický, Czech.

- Roderick O, Schnyde U (2003) Reconstructing early intervention after trauma. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Mlčák T (2008) Determinanty vztahující se k participaci ve sportovní činnosti u osob s tělesným postižením. Nepublikovaná bakalářská práce, [Unpublished Bachelor Thesis.] Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého, Fakulta tělesné kultury, Czechia.

- Skovajsová E (2011) Determinanty zapojení do pohybových aktivit po traumatu. Nepublikovaná bakalářská práce. [Unpublished Bachelor Thesis] Univerzita Palackého, Fakulta tělesné kultury, Olomouc, Czechia.

- Protić M (2010) Psychosocial aspects of player´s engagement to the sitting volleyball. Nepublikovaná magisterská práce, [Unpublished Master Thesis.] Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého, Fakulta tělesné kultury, Czechia.

- Pajević M (2015) The determinants of participation in physical activities after the war trauma in the national sitting volleyball team of Bosnia and Hercegovina. Nepublikovaná magisterská práce, [Unpublished Master Thesis.] Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého, Fakulta tělesné kultury, Czechia.

- Vute R (2009) Teaching and coaching volleyball for the disabled: foundation course handbook (2nd edn). Faculty of education, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia, pp. 1-59.

- Kwok Ng (2012) When sitting is not resting. Bloomington: Author House.

- CDDS (1987) European Charter of Sport for All: Handicapped People. France.

- Selye H (1956) The stress of life. Mc Graw-Hill, New York, USA.

- Cox RH (2002) Sport psychology: concepts and applications. Mc Graw Hill Publishing: location?

- Franks AM, Williams AM, Reilly T, Nevill AM (2002) Talent identification in elite youth soccer players: physical and physiological characteristics. In W Spinks, T Reilly, A Murphy (Eds.), Science and Football IV, London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, USA.

- Gibson B (2002) Determining the role of the parents in preparing the young elite players for A.F.L. career. In W Spinks, T Reilly, A Murphy (Eds.), Science and Football IV. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, USA.

- Hošek (1980) Psychologie sportu.[Sport psychology] Praha: Státní pedagogické nakladatelství, pp. 55-57.

- Protic M (2012) Psychosocial aspects of sitting volleyball players´ in sports engagement. Acta Kinesiologica, 5(2): 12-16.

- Selye H (1983) The stress concept: past, present and future. In CL Cooper (Edn) Stress research: issues for the eightees. David Willey, New York, USA

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.