Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Vitamin A and its Derivatives- Retinoic Acid and Retinoid Pharmacology

*Corresponding author: George Zhu, Department of Oncology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran.

Received: April 30, 2019; Published: May 29, 2019

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.03.000656

Abstract

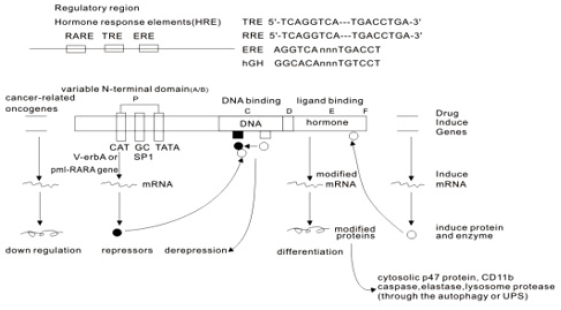

Retinol (Vitamin A) and its derivative retinoic acid (RA) are essential in the control of epithelial cell growth and cellular differentiation. Retinoid is indispensable in vision and RA inhibits the growth of some malignant cells. RA has also striking effect on pattern formation in developing and regenerating limbs, and also a potent morphogen in chick limb bud. Retinoic acid (RA) proved therapeutic benefits in cancer prevention, in skin diseases and in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). The elucidation of the molecular basis of vitamin A and its retinoid pharmacology emerged as paradigm for the connection between RA and its structure of RA receptors(RAR), oncogenic pml/RARa as constitutive transcriptional repressor that block myeloid differentiation at promyelocytic phenotype, and the molecular model of retinoic acid action in a special APL. A molecular model is further revised. As an approach to APL treatment, one possible the action of retinoic acid (RA), A consensus sequence (TCAGGTCA motif) has been postulated for thyroid hormone (TRE) and retinoic acid responsive element (RARE)-containing in the promoter region of target genes. High dose of RA-RARE-PML/RARa complexes in intracellular localization appears to relieve repressors from DNA-bound receptor, including the dissociation of corepressor complexes N-CoR, SMRT and HDACs from PML-RARa or partially PML-RARa/RXR. Also release PML/RARa -mediated transcription repression. This transcriptional derepression occurs at RARa target gene promoter. Consquentially, PML-RARa chimera converted receptor from a repressor to a RA-dependent activator of transcription. The resulting pml-RARA oncoprotein proteolytic degradation occurs through the autophagylysosome pathway and the ubiquitin SUMO-proteasome system(UPS) as well as caspase 3, or lysosomal protease (cathepsin D) enzyme or/and EI-like ubiquitin-activating enzyme(UBEIL) induction. Accordingly the expression level of PML-RARa downregulated. PML protein relocalizes into the wild-type nuclear body (PML-NB) configuration or a truncated PML-RARa fusion fragment detected or/and the wild-type RAR upregulated. An effect is to relieve the blockade of pml/RARa-mediated RA dependent promyelocytic differentiation and retinoic acid (9-cis RA, ATRA, Am80) in APL therapy (See figure by Zhu G, January 1991, revised in 2012). Here, RA can overcome the transcriptional repressor activity of pml/RARa.The oncogenic pml/RARa uncover a pathogenic role in leukemogenesis of APL through blocking promyelocytic differentiation. This oncogenic receptor derivative pml/RARa chimera is locked in their “off” regular mode thereby constitutively repressing transcription of target genes or key enzymes (such as AP-1, PTEN, DAPK2, UP.1, p21WAF/CCKN1A) that are critical for differentiation of hematopoietic cells. This is first described in eukaryotes.

Keywords: Vitamin A; Retinoic acid and retinoid pharmacology; Gene transcription; Molecular model of RA

Introduction

In vivo, the fat soluble Vitamin A (retinol) can be reversibly metabolised to the aldehyde (retinal) which can in turn, be further oxidised in a non-reversible manner to retinoic acid (RA). Enzymes that oxidize retinol to retinaldehyde belong to two classes: the cytosolic alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs) belonging to the mediumchain dehydrogenases/ reductase family; and microsomal shortchain dehydrogenases/reductases (retinol dehydrogenases, RDHs [1]. The next step in RA synthesis is the oxidation of retinaldehyde to RA, which is carried out by three retinaldehyde dehydrogenases (RALDHs): RALDH1, RALDH4 and RALDH3 [1,2]. The orange pigment of carrots (beta-carotene) can be represented as two connected retinyl groups, which are used in the body to contribute to vitamin A levels [3]. The physiological and biological actions of this class of substances centre on vision, embryonic development and production, cellular growth and differentiation, skin health, and maintenance of immune function.

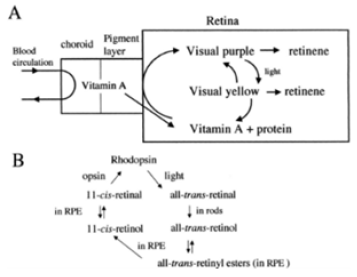

Initial studies had focused on vitamin A deficiency and its major consequences: night blindness and Xerophtalmia. Fridericia and Holm [4] investigated the influence of dietary A in the rhodopsin of the retina. Clearly, the rats lacking the fat-soluble vitamin A had a defect in the function of visual purple. Yudkin [5] achieved one of the earliest identifications of vitamin A as a component of the retina. Subsequently, Wald [6] determined the amount of vitamin A present in pig retinas. Wald G [7,8] was well established the visual cycle: light decomposed rhodopsin to retinal and opsin. Retinal could either recombine with opsin to reform rhodopsin or it converted to free retinol. Retinol could reform rhodopsin, but only in the presence of the RPE(Kuhne). The further structure and metabolism of retinoids implicated that retinaldehyde was the visual pigment.

Biochemistry of Vitamin A

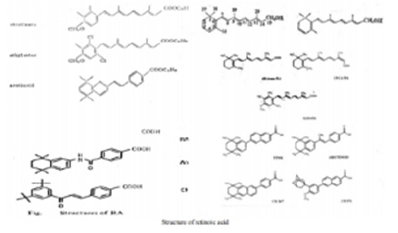

There is now a well-developed medicinal chemistry of RA (Figure 1 & 3) [9]. The group of pharmacologically used retinoids include vitamin A (all-trans retinol), tretinoin (all-trans retinoic acid), isotretinoin (13-cis retinoic acid) and alitretinoin (9-cis retinoic acid). The monoaromatic retinoids include acitretin and etretinate. The third generation polyaromatic retinoids include bexarotene and tazarotene. In view of this broad spectrum of pharmacological activity, these substances provide useful to treat multifactorial dermatological disorders and other hematological disorders such as acute promyelocytic leukemias (APL) (Figure 1 & Figure 2) [8,10-12].

Function of Vitamin A and its Physiological Role

Vision

Vitamin A is needed by the eye retina,11-cis-retinal (a derivative of vitamin A) is bound to the protein “opsin” to form rhodopsin (visual purple) in rods cells [8], the molecule necessary for both low light (scotopic vision). As light enters the eye, the 11-cis-retinal is isomerized to all-trans retinal in photoreceptor cells of the retina. This isomerization induces a nervous signal (a type of G regulatory protein) along the optic nerve to the visual center of the brain. After separating from opsin, the all-transretinal is recycled and converted back to the 11-cis-retinal form via a series of enzymatic reactions. The all-trans- retinal dissociates from opsin in a series of steps called photo-bleaching. The final stage is conversion of 11-cis-retinal rebind to opsin to reform rhodopsin in the retina [6-8] (Figure 2) vision cycle. Kuhne showed that rhodopsin in the retina is only regenerated when the retina is attached to retinal pimented epithelium (RPE) [8]. As the retinal component of rhodopsin is derived from vitamin A, a deficiency of vitamin A inhibit the reformation of rhodopsin and lead to night blindness. Within this cycle, all-trans retinal is reduced to all-trans retinol in photoreceptors via RDH8 and possible RDH12 in rods and transported to RPE. In the RPE, all-trans retinol is converted to 11- cis retinol, then 11-cis retinol is oxidized to 11-cis-retinal via RDH5 with possible RDH11 and RDH11 [1]. This represent each RDH for the roles in the visual cycle (Figure 2) .

Figure 3: A well developed medical chemistry of retinoic acid (RA). The all-trans and 13-cis forms of retinoic acid,two isomers of RA,are equally effective inhibiting proliferation. Retinyl acetate,and retinal(Vitamin A) are less potent inhibitor. Am80(Tamibarotene) is more potent inhibitor. The chemical structures of more potent analogues involved from labile flexible polyene structures to aromatic stable moieties are shown[9,10].

Embryonic Development

More recent, vitamin A and its metabolites play a key importance in embryo morphogenesis, development and differentiation in normal tissues. Retinoic acid (RA) is lipophilic molecule that act as ligand for nuclear RA receptors (RARs), converting them from transcriptional repressor to activators [2,11,12] in RA signaling pathway. It has been demonstrated that retinoic acid was identified as a morphogen(teratogen) responsible for the determination of the orientation of the limb outgrowth in chicken [13,14] and its retinoic acid receptors (RARs) appear at early stage of human embryonic development in certain types of tissues [15]. Vitamin A play a role in the differentiation of this cerebral nerve system in Xenopus laevi. The other molecules that interact with RA are FGF-8, Cdx and Hox genes, all participating in the development of various structures within fetus. For instance, this molecule plays an important role in hindbrain development. Both too little or too much vitamin A results in the embryo:defect in the central nervous system, various abnormalities in head and neck, the heart, the limb, and the urogenital system [15]. With an accumulation of these malformations, an individual can be diagnosed with DeGeorge syndrome [2].

Dermatology

Vitamin A, in the retinoic acid form, plays an important role in maintaining normal skin health through differentiating keratinocytes (immature skin cells) into immature epidermal cells. In earlier studies, Frazier and Hu (1931) [16] made the observation that both hypovitaminosis A and hypervitaminosis A provokes epithelial alterations together with decreased keratinization and hair loss. At present,13-cis retinoic acid (Isotretinoin) in clinical used to acne treatment. The mechanism was shown to reducing secretion of the sebaceous glands, triggering NGAL (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin) and other gene expression and selectively inducing apoptosis [17]. But precise action of retinoid therapeutic agents in dermatological diseases are being researched.

Hematopoiesis

vitamin A is important for the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell dormancy [18]. Mice maintained on a vitamin A-free diet loss HSCs (hematopoietic stem cells), showing a disrupted re-entry into dormancy after exposure to inflammatory stress stimuli. This condition highlight the impact of dietary vitamin A on the regulation of cell-cycle mediated stem cell plasticity [19]. In vitro, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) stimulates at least two-fold the clonal growth of normal human CFU-GM and early erythroid precursor BFU-E [20]. Cis-RA stimulates clonal growth of some myeloid leukemia cells. In suspension culture, there was an increase in cell number at day 5 in the presence of RA in half of 31 samples, which suggest that RA may play a role in the proliferation and survival of certain leukemia clones in vitro [21,22].

In contrast to the enhancement of normal hematopoietic proliferation, RA (10-6 - 10-9 mol/l) is capable of inducing differentiation of the F9 mouse teratocarcinoma, HL-60 cells [23,24] and some blasts from patients with promyelocytic leukemia [23]. Maximum HL-60 differentiation (90% of cells) occurs after a 6 day exposure to 10-6mol/l retinoic acid. Further in vitro studies found that retinoic acid induced differentiation of leukemic blast cells in only 2 of 21 patients with AML, both of these patients had promyelocytic variant [24]. These data suggest that retinoids may induce maturation of promyelocytes. Retinoic acid also inhibits the proliferation of other dermatological malignant cells (Myger,1975; Peck,1975).

Maintenance of Immune Homeostasis

There is a link between retinoid and immune homeostasis. RA is crucial for maintaining homeostasis at the intestinal barrier and equilibrating immunity and tolerance. de Mendonca Oliveira LM and colleagues [25] have in detail illustrated the impact of retinoic acid on immune cells and inflammatory diseases. After the absorption and metabolism of vitamin A and its precursor(β-carotene) into RA by alcohol dehydrogenase(ADH) and retinal dehydrogenase(RALDH) in CD103+ DC cells in gut, RA plays an important roles in mucosal immune response by promoting differentiation of Foxp3+ inducible regulatory T (Treg) cell and immunoglobulin(Ig) A production. In this process, RA promote dendritic cells to express CD103 and to produce RA. Vitamin A and zinc deficiency (VAD) lead to a decrease of serum IgA. Oral administration of RA in VAD mice can efficiently be reestablishing IgA production. These effects are mediated by an increase of the early B cell factor 1(EBF1) and paired box protein-5(pan-5) transcription factors, which are critical for B cell development. RA accelerates the maturation of human B cells and their differentiation into antibody-secreting plasma cells.

In addition, RA induces the homing of innate immune cells, such as innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) besides regulatory and effector T and B cells, to the gut. Among three ILCs, ILC3 depend on the transcription factor retinoic acid receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor gamma (RORrt) and secrete IL-17 and IL-22. During infections, RA can induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines by dendritic cells (DCs), promoting the generation of effector T cells and restoring the balance of Th17/Treg cells in the GALT (gut-associated lymphoid tissue), and the protection of the mucosa. Moreover, vitamin A is capable of inducing the IL-6- driven induction of proinflammatory T(H) 17 cells, promoting antiinflammatory T reg cells differentiation, regulating the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory immunity [26,27].

Retinoid Acids in MDS Treatment

The geometric isomer of the naturally occurring retinoic acid is 13-cis retinoic acid (13-CRA). Based on in vitro and in vivo antineoplastic activity, this agent has entered clinical trials for a variety of neoplasms including MDS. Retinoic acid is one of the biological inducers of differentiation that has been preliminarily tested in patients with preleukemia. Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) are a group of hematopoietic disorders characterized by ui- or multilineage maturation defects of the bone marrow [28]. Differentiation induction therapy is used in MDS to improve this maturation defects and induce a multilineage clinical response in a subgroup of MDS patients.13-CRA may have moderate effect on 20-30% of patients with MDS [29]. A various of combination therapy with 13-cis RA and growth factors G-CSF or erythropoietin (EPO) improve impaired cytokine secretion (IL-1beta, IL-6, IL-8) from monocytes [30]. In a prospective multicenter study, EPO-beta- ATRA [31] or EPO-13-cis RA [32] combination appears to erythroid response reaching about 36%-60% of therapeutic efficacy in anemia of low/intermediate risk MDS(LDMDS) (marrow blasts < 10% or excluding RARBt). More data analysis, erythroid response maintained an independent positive impact on survival, particularly in non-RARE patients in the first 3 years from diagnosis (90% survival in EPO responders compared to 50% of non-responders) [33]. Zhu [34] successfully conducted a CR patient with refractory anemia with multilineage megaloblastic dysplasia following traditional medicine and erythropoiesis-stimulating agent vitamin B12 and folate growth factor. His peripheral parameters presented pancytopenia (hemoglobin 59g/l, red blood cell count 1.9x1012/l, leukocyte count 2.6x109/l, platelet value 11.8x109/l).

He remained well over 10 years. While another MDS had its unequivocal evidence of disease progression in response to phytohemagglutinin (PHA), inducing the generation of interleukin-2, accelerating the number recovery of CFU-S and initiating DNA synthesis of cells. She had 2.5% blast plus promyelocytes in ~70% cellular marrow before beginning PHA, and 20.7% blast plus promyelocytes in a 90% cellular marrow after ten days (total dosage 250mg) of PHA. Venditt etal [35] conduct that 23 patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (HRMDS) were treated with a 10 days course of oral ATRA (45mg/m2) and subcutaneous low-dose cytosine arabinoside (LDARAc) given at the dose of 20mg twice a day. In all cases (RAEB9, RAEBt9 and CMML4) [36] bone marrow blasts infiltration was greater than 10% (12-30%). Overall, 5(23%) of 22 patients achieved complete responder and 2(9%) as partial responders. The overall median survival was 8 months (range 1-27months), whereas the median survival of responders was 16months(8-27months), the median duration of response was 11months(2-21months). It seems that the combination of ATRA and LDARA-c may be effective in approximately 30% of HRMDS patients [35].

Valproic acid (VPA) has been used as an anticovulsant for decades. VPA is a potent inhibitor of histone deacetylases (HDAc). It can modify the structure of chromatin allowing recruitment of transcription factors to restore epigenetically suppressed genes. VPA has been shown to posses antiproliferative activity and to overcome the differentiation block in leukemia blast cells [37]. Some clinical trials with VPA monotherapy or in combination with ATRA have been reported in MDS. In a piloty study of Kuendgen and colleagues [38- 40] patients with MDS or AML secondary to MDS were treated with VPA monotherapy or with ATRA later resulting in a 44% of response rate. In the follow-up study of 43 patients, an even higher response rate of 52% was observed in those low-risk MDS patients, while for the patients with excess blasts (RAEB) and CMML response rates were 6% and 0% respectively, which implicate the difference of MDS subtypes. In another trials, Siitonen etal [41] reported that according to IWG criteria,3 patients(16%) of 19 MDS responded to treatment following VPA,13-cis RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 combination. All the responses were hematological improvement. One patient responded to the treatment with an increase in platelet value from 67x109/l to 105x109/l. His peripheral blood and bone marrow blast cells decreased from 4% to 0% and from 19% to 7%, respectively. Furthermore, the disease remained stable in 11 patients but progressed in 5 during treatment. This is encouraging results.

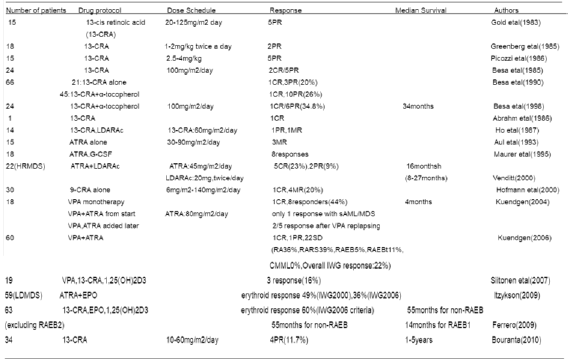

A series of these studies are summaried in (Table 1). While some patients experienced improvement in peripheral blood counts, complete responses were reported in only a small proportion of these studies [42-43]. The sole exception was a patient who presented with 29% marrow blasts and 90% abnormal metaphases with 13-cis RA. He obtained a complete clinical and cytogenetic remission therapy [44-49]. This clinical response to 13-cis RA drug was due to in vivo growth inhibition of malignant monocytoid clone [50]. Continued follow-up of this study in this field will be of interest [51-54] (Table 1).

Retinoic Acids in Skin Disease

Vitamin A is necessary for normal epithelial cell differentiation and maturation [55-57]. Retinoids influence on skin keratocyte proliferation, epidermal differentiation and kerintinisation. Those retinoids including natural and chemically synthesized vitamin A derivatives are common used as systemic and topical treatment of various skin disorders. At present there have well developed three generations: the naturally occurring retinoids (all-trans retinol, Aretinoin, Isotretinoin, Alitretinoin) the monoaromatic retinoid and the polyaromatic retinoid derivatives [58].

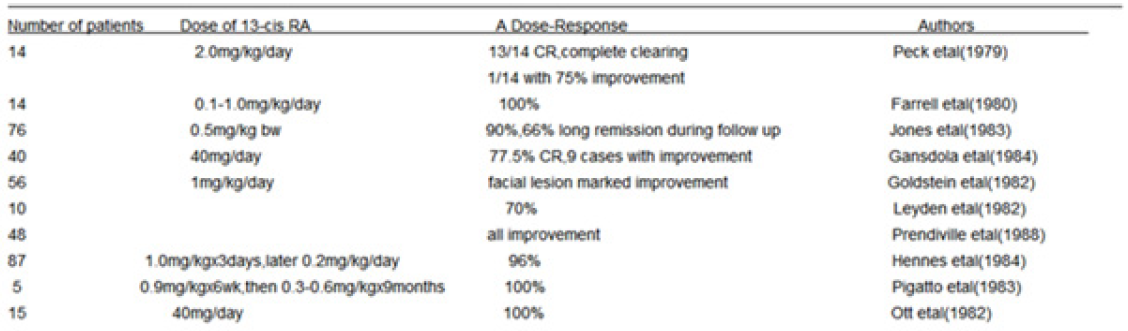

Isotretinoin is an orally active retinoic acid derivative for the treatment of acne (papulo- pustular,nodulo-cystic, conglobata) [59],since it shows an excellent efficacy against severe refractory nodulocystic acne. Peck’s [60] original observation in 1978-79 of the effectives of 13-cis RA in cystic acne has been well supported. In double-blind studies using small doses of 13-cis RA regimen, Farrell [61] in 15 patients, Jones [62] in 76 patients, Plewig [63] in 79 patients and Rapini [64] 150 patients reporting have confirmed this results. A summary study of limited review on 365 affected persons are presented in (Table 2). The drug action involves an inhibition of sebum excretion rate(SER) in sebaceous glands and production rate of free fatty acids[60,61,65-68] through trigerring NGAL (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin) expression [17] normalise follicular keratinisation [69] and the decrease in colonisation of propionibacterium acnes and associated inflammation in skin surface microflora [70].This response, mediated by toll-like-receptor 2(TLR2), is increased in acne patients due to high expression of TLR2 [71] (Table 2).

Figure 4: An advanced squamous cell carcinoma of skin before(left) and after(right) isotretinoin [57].

Encouraging results have also been used 13-cis RA in small numbers of patients with rosacea, Gram-negative folliculitis, Darier’s disease, ichthyosis and pityriasis rubra pilaris [72,73]. In the treatment of rosacea, isotretinoins led to a significant reduction of erythemia, papules and pustules in several studies [72,73]. During treatment of rosacea,13-cis RA act as a potent anti-inflammatory and sebum-suppressive agent. Long-lasting remission can be reported for first patient over 12 months [72]. The use of low dose isotretinoin (0.15-0.3mg/kg bw daily) showed high efficacy and was well tolerated. Isotretinoin is only partially effective in psoriasis, in contrast etretinate which is effective in psoriasis but ineffective in severe acne. Promising, some trials have reported with isotretinoin in patients with squamous and basal cell carcinomas [74,75] cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [56] recurrent malignant glioma [76] malignant eccrine poroma [77] and keratoacanthomas [78,79] and xeroderma pigmentosum with squamous cell carcinoma [79]. In literature, there were at least 10 CR patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Skroza etal [74] reported a CR patient with well-differentiated SCC following the daily dosage of 0.5mg/kg/day for 5 months. Dring 1-year follow up, he remained all in normal range. Using combination chemotherapy and isotretinoin for 4 months, Zaman [80] reported a complete clinical remission of tumors in a case of 15 year old female of xeroderma pigmentosum with SCC. Another collection of four SCC of skin obtained CR through isotretinoin at daily dose of 1mg/ kg/day twice a day for 4 months (Figure 4) [57]. The mechanism may involve the modification of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and certain protein kinase. At present, It has clearly known the results that amplified (50-fold EGF receptor in SCC relative to normal skin keratinocytes) or mutant EGFR is oncogenic in origin of some SCC [81]. This oncogenic receptor EGFRvIII has also been found in malignant glioma and invasive breast carcinoma [82-89]. Zhu [90] conduct a short CR using chemotherapy and topical 5% Fu of retinoic acid ointment in a 75-year old patient with SCC. She had a 8x5cm rodent ulcer in her left ear and facial area. A shrinkage of irregular and harden marginal valgus converted to flat and superficial red and scar noted after one month treatment. These findings suggest that retinoids may be effective and well-tolerated therapy for advanced epidermoid SCCs in some studies [91-95] (Figure 4) .

ATRA in patients with gastric cancer (GC)

Recently [96], two cohorts of group presented ATRA trials on patients with GC. Jin etal presented a better benefits of gastric dysplasia with omeprazole and sucralfate and the addition of ATRA (68% vs 37%) compared to patients treated with omeprazole and sucralfate alone. Hu etal also showed that ATRA significantly prolong overall survival following the combination of conventional chemotherapy. ATRA anticancer mechanisms of action against GC cells included cell cycle blocking and differentiation initiation(p21WAF1/CIP1 induction, decreased ERK/MAPK pathway), decreased expression of HER2 oncogenic receptor in patient’s gastric mucosa, apoptosis initiation and inhibiting CSC(cancer stem cell) properties such as tumorspheres formation and patient derived xenografts(PDX) growth in mice. In GC cells, CD44+ stem/progenitor cells and a high ALDH (aldehyde dehydrogenase, R-ALDH, ALDH1A1 and ALDH1A3) activity could be considered as putative targets to inhibit tumor growth, to overcome resistance to cancer therapy and to improve GC prognosis.

The-Structure-of-Retinoic-Acid-Receptors-Molecular-Basis-of-Retinoic-Acid-Action-and-the-RAR-Gene-Transcription

RARs structure

The retinoic acid receptors (RAR) belong to the large family of ligand responsive gene regulatory proteins that includes receptors for steroid and thyroid hormones [97]. There are three retinoic acid receptors (RAR), RARα, RARβ and RARγ which are conserved throughout vetebrates encoded by their different RAR (chr 17q21, chr 3p24 and chr12q13) gene, respectively. The RARA contains 462 amino acids(aa) [98,99] RARB consists of 455aa [100] and RARG contains 454aa [101] respectively. The RAR is a type of nuclear receptor which act as a transcription factor that is activated by both all-trans RA and 9-cis RA. The RARs have different functions and may activate distinct target genes. The RARa is expressed in a wide variety of different hematopoietic cells [98,99] the RARβ in a variety of epithelial cells [100] and the RARr in differentiation of squamous epithelia and human skin tissue [101,102]

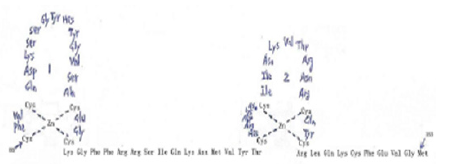

All RARs contain a variable N-terminal region(A/B), a highly conserved cysteine-rich central domain(C) responsible for the DNA binding activity, and a relatively well-conserved C-terminal half(E) functionally its role in ligand binding and nuclear translocation. These three main domain are separated by a hinge region(D) [12,97,102].The central DNA binding domain(88-153aa) exhibits an array of cysteine residues compatible with the formation of two so-called zinc finger(Miller,1985).Each of them a zinc atom tetrahedrically coordinated to four cysteine and each of the hypothetical zinc finger is encoded by a separate exon of the receptor gene (Figure 5) Zinc finger 1, 88-108aa, Zinc finger 2, 124- 148aa] [97-103].The N-terminal zinc finger of the DNA binding domain confers hormone responsiveness to HREs, determing target gene specificity and responsible for functional discrimination between HREs whereas the C-terminal finger contains the sugarphosphamide backbone of the flanking sequences [103,104] (Figure 5) .

Figure 5:Amino acid sequence of the DNA binding domain of the hRARa into two putative zinc–binding finger (Figure from George Zhu a feeling for scientific drawing based on Evans RM, Science, 1988, 240:899- 895; Beato M,Cell,1989, 56: 335-344; Giguere V,Nature,1987;330:624-29; Petkovich M, Nature, 1987,330: 444).

The molecular basis of retinoic acid action and the RAR gene transcription

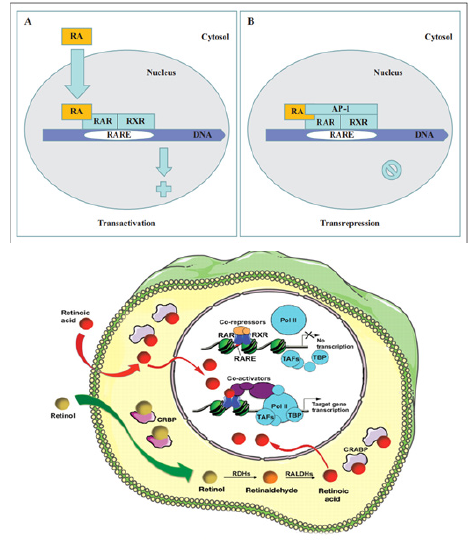

Retinoic acid (RA) is a lipophilic signal molecule which is able to induce acute and direct activation of the expression of specific genes supports its molecular model of action that resembles that of steroid hormones [105]. The cellular retinoic acid-binding protein (CRABP) may be involved in this transfer [9,10]. In the nucleus, RA receptors (RAR) function as a heterodimer with retinoid X receptors (RXRs) [106-109]. RAR/RXR can bind to DNA motif at RA-response elements (RAREs, also HRE) in the regulatory sequences of target genes in the absence of ligand, thereby interacting with multiple protein complexes that include co-repressors N-CoR [110] SMRT [111] and histone deacetylases (HDACs), and maintaining gene repression. Here, RAREs consist of a direct repeat of a core hexameric sequence 5’ (A/G)G(G/T)TCA-3’ [112] or of the more relaxed 5’-(A/G)G(G/T) (G/T)(G/C)A-3’ motif, separated by 1,2,5 bp [113]. A corepressor represses expression of genes by binding to and activating a repressor transcription factor, the repressor in turn bind to target gene’s operator including RARE sequence, then blocking transcription of that gene (see corepressor-wikipedia). Transcriptional regulation thus drives from the binding of hormone-receptor complexes to RARE sites on target DNA [12,97,103]. In the presence of RA(all-trans RA,9- cis RA),binding of the RA ligand to RAR alter the conformation of the RAR, a conformational change in the DNA-bound receptor leads to the release of co-repressor complexes associated with the RAR/RXR dimer and the recruitment of co-acitivator complexes. These induce chromatin remodeling and facilitate assembly of the transcription pre-initiation complex including RNA polymerase II (Pol II) [114], TATA-binding protein (TBP) and TBP-associated factors (TAFs) [2,12,103,115,116] (Figure 6). Subsequently, transcription of target genes is initiated. This also represent liganddependent transcriptional activation which mediated by nuclear receptors. Like thyroid hormone receptor (THR) [117,118] retinoic acid act as ligand for RARs, converting RARa from transcriptional repressor to activators [2,12,119-122]. Numerous RAR target genes after RA induction have been identified including genes within retinoid pathway, such as RARB,Crbp1/2 (Rbp1/2),Crabp1/2 and CYP26a1.And also, several members of HOX gene family, including HOXa1,HOXb1,HOXb4 and HOXd4,and other genes Tshz1 and Cdx1 [123] the function of which has been demonstrated in vivo in the normal roles of retinoids in patterning vertebrate embryogenesis, early neurogenesis, cell growth and differentiation (Figure 6).

Figure 6:Retinoid receptor-dependent gene regulation [116] & (b): Gene regulation by retinoic acid signalling [2].

Molecular Model of the Gene Regulation of Retinoic Acid Action in APL

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is a clonal expansion of promyelocytic precursors . Retinoic acid(RA) (initial 13-cis RA, later ATRA and tamibarotene) plus chemotherapy is currently the standard of care [124-131]. APL has a very good prognosis, with long-term survival rates up to near 70%-90% [132]. Molecular analysis has uncovered the facts that approximately 98% of APL, RARa translocates and fuses with the PML gene on chromosome 15 [133-136]. The resulting RAR chimeric genes encode pml/RARa fusion protein, which is specifically expressed in the promyelocytic lineage [20]. In addition to oncogenic receptor derivative pml/RARa [108,137-139] the translocation involves oncogenic TBL1XR1- RARB [140] and NUP98/RARG [141] and oncogenic PML-RARG [142] which share high homolog (90%) of three RAR family that were also detected in APL rare cases.

Most studies have shown in APL that oncogenic pml/ RARa act as constitutive transcriptional repressor that blocks neutrophil differentiation at the promyelocyte stage. Without its ligand, retinoic acid (RA), PML-RARA functions as a constitutive transcriptional repressor of RARE-containing target genes, abnormally associating NcoR/HDACs complex and blocking hematopoietic differentiation. In the presence of pharmacological concentration of RA (about 350ng/ml), RA induce the corepressors NcoR/ HDACs dissociation from PML-RARA, thereby activates transcription and stimulate differentiation [11,12,108,139]. In vitro by using a dominant negative RAR construct transfected with interleukin 3(IL-3)-dependent multipotent hematopoietic cell line (FDCP mix A4) and normal mouse bone marrow cells, GM-CSF induced neutrophil differentiation was blocked at the promyelocyte stage. The blocked promyelocytes could be induced to terminally differentiate into neutrophils with supraphysiological concentration of ATRA [143]. Similarly, overexpression of normal RARa transduced cells displayed promyelocyte like morphology in semisolid culture,and immature RARa transduced cells differentiate into mature granulocytes under high dose of RA(10-6M) [144]. Moreover, mutation of the N-CoR binding site abolishes the ability of PML-RARa to block differentiation [145,146]. Therefore, ectopic expression of RAR fusion protein in hematopoietic precursor cells blocks their ability to undergo terminal differentiation via recruiting nuclear corepressor N-CoR/histone deactylase complex and histone methyltransferase SUV39H1 [147]. In vivo, transgenic mice expressing PML-RARA fusion can disrupt normal hematopoiesis, give sufficient time, develop acute leukemia with a differentiation block at the promyelocytic stage that closely mimics human APL (APL-like syndrome, even in its response to RA in many studies. These results are conclusive in vivo evidence that PML/ RARa is indeed oncogenic, and oncogenic pml/RARa is etiology of APL pathogenesis [148-150]. This also represent a steroid receptor in tumorigenesis (Figure 7).

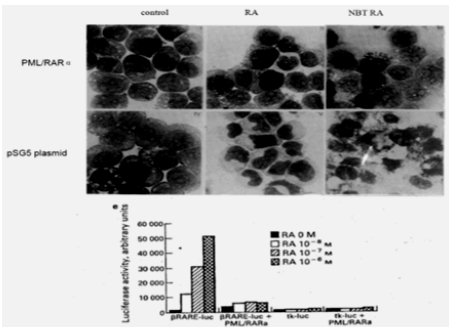

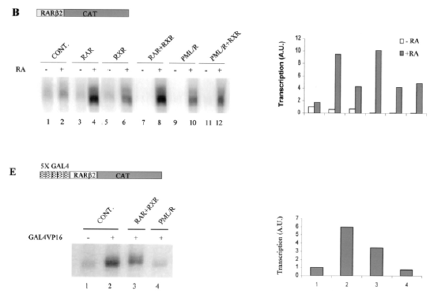

Moreover, in Rousselot’s group experiments, HL-60 cells transfected with 15-30ug of PML-RARa fusion in culture show no features of granulocytic differentiation after 7 days of incubation with 10-7,10-6 uM RA (5.5-9.5% of differentiated cells by the NBT test). At 5ug of PML-RARa plasmid concentration, the blockage of RA-dependent myeloid differentiation could be overcomes with high doses(10-6M) of RA (99% of differentiated cells by NBT test) (Figure 8) [151]. The results clearly indicate that PMLRARa mediated transcriptional repression, as well as PML-RARa oncoprotein blocks RA-mediate promyelocyte differentiation. (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Expression of pml-RARa in HL-60 cells blocks ATRA-induced promyelocytic differentiation a(in the presence of 10-7 M RA, top), and transcriptional repressive properties of pml-RARa in human myeloid cells as βRARE-luc assay(bottom) [151].

By using Xenopus oocyte system to uniquely the comparison of the transcriptional properties of RAR and PML-RAR is due to the lack of endogenous nuclear receptors and the opportunity to evaluate the role of chromatin in transcriptional regulation. The results shown in (Figure 9) demonstrated that, indeed, PML-RARA is a stronger transcriptional repressor that is able to impose its silencing effect on chromatin state even in the absence of RXR. Only pharmacological concentration of RA,pml/RARA become transcriptional activator function [139]. (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Shows pml/RARa as a constitutive transcriptional repressor in xenopus oocyte system, as measured by RARE3 CAT and GAL4 assay [139].

In vitro experiments, ATRA induce pml-RARA itself cleavage into a 85-97kd delta PML-RARA product (a truncated pml/RARA form) in RA sensitive NB4 [152-156] (Figure 10). Delta PML-RARa is not formed in ATRA differentiation resistant NB4 subclones [152,155] which indicate the loss of PML/RARa may be directly linked to ATRA-induced differentiation [152,155].This induction of of PML-RARa cleavage and degradation by RA(ATRA,9-cis RA,Am80) involve the proteasome-dependent [152-154] and caspase mediated pathway [155] or independent of proteasome and caspase cleavage[156] and possibly ubiquitin-activating enzyme EI-like(UBEIL) induction in NB4 cells. This is reason that proteasome inhibitor MG-132 and caspase inhibitor ZVAD do not block ATRA-induced pml/RARa cleavage and differentiation whereas this delta pml-RARA is blocked by RARA itself antagonist Ro-41-5253 [156].The proteasome-dependent pml/RARA degradation, by using proteasome inhibitor lactacystin test, allows APL cells to differentiation by relieving the differentiation block [153]. These data suggest a set of multiple molecular mechanisms for restoration by RA induced myeloid differentiation in APL cells. (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Shows delta pml/RARa cleavage products independent of proteasome and caspase in the presence of ATRA(a,b), and pml/RARa act as transcriptional repressor even in the presence of ATRA(0.01uM,1uM) in RARE-tu-luc assay while delta pml/ RARa is less potent activator of RARE-tk-leu activation than wild-type RARa(c) in NB4 cells [155].

Next we further examine the pml/RARa three region functions,in vitro deletion of the RARa DNA binding domain decreased the ability of pml/RARa to inhibit vitD3 and TGFinduced the myeloid precursor U937and TF-1 cell differentiation [145]. This is also supported by functional analysis of DNA binding domain mutation in vitro. The RARa zinc finger is a sequencespecific DNA binding through which RARa contacts the RA target genes. Moreover, deletion of PML coiled-coil region also blocked the differentiation capacity of TF-1 cells [145]. The coiled-coil region directs the formation of pml/RARa homodimers tightly interact with the N-CoR/HDACs complex, so that transcriptional derepression cannot occur at RARA target gene promoter even if the presence of ATRA [RA resistant, 12,157]. In vitro, using established subclones of NB4 resistant to both ATRA and 9-cis RA, they were significantly less able to stimulate transcription of a RARE driven CAT-reporter gene induction by ATRA and showed altered DNA binding activaty on a RARE [158]. In the resistant cases, mut PML stabilizes PML-RARa [159]. PML-RARA with ligand-binding domain (LBD) mutation, ligand RA binding with LBD is impaired. These results have clearly shown that PML protein dimerization and RARa DNA binding domain are indispensible for the myeloid precursors differentiation which was blocked by PML/RARA and eventually leukemic transformation.

In accordance,the pml/RARa/RXR target genes is found to block differentiation by consitutively silencing a set of RA-responsive genes in the control of hematopoietic precursor cells. Five major transcription factors, Ap-1 [160] C/EBPepsilon [161,162] Pu.1/ DAPK2 [163] PTEN [164] and p21WAF/CCKN1A [165] directly regulate genes important in myeloid differentiation. PML/RARA fusion is oncogenic transcriptional repressor of five genes. Inhibited expression or functions of these five transcription factors lead to a block in myeloid differentiation, which is a hallmark of APL.

In vitro cotransfection of pml/RARA with plasmid expressing AP-1 of c-Jun and c-fos proteins in MCF-7 cells, by using CAT assay, PML-RARa is a repressor of AP-1 transcriptional activity in the absence of RA while RA treatment converted the chimera into a strong activator [160]. Since high AP-1 activity is associated with differentiation of leukemic cells in several context [160] the stimulatory effects in the presence of RA could be relevance to its reversal by provoking differentiation. Another, in pml/RARacontaining cell lines, a close link exists between induction of differentiation and induction of C/EBP epsilon expression [161]. C/ EBPepsilon knockout mice had a block in myeloid differentiation [162]. In absence of retinoic acid (RA), induction of pml/RARa expression in U937PR9 cells stably transfected with zinc-inducible pml/RARa suppressed the expression of C/EBPepsilon. In contrast to its repression, in the presence of a pharmacologic concentration of RA, pml/RARa significantly increased the level of C/EBPepsilon expression in a time and dose-dependent manner [161]. The findings implicate that C/EBPepsilon is critical downstream target gene in RA-dependent granulocytic differentiation in the treatment of APL [163-165].

Phosphotase and Tensin homolog (PTEN) is a protein and lipid phosphatase, which plays a pivotal dual role in tumor suppression and self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells as its promoting exhaustion of normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and generation of leukemia-initiating cells (LICs) [166,167]. PTEN expression is downregulated in APL, while ATRA treatment increases PTEN leves by inducing PU.1 transcriptional activity via pml/RARa degradation, allowing the binding of PU.1 in PTEN promoter, in turn promotes PTEN nuclear re-location and decreases expression of the PTEN target Aurora A kinases. Therefore, PTEN is one of the primary target gene of oncogenic pml/RARa in APL

Importantly, restoring DAPK2 expression in PU.1 knockdown APL cells partially rescued neutrophil differentiation [168]. In addition, DAPK2 interacts with other cyclin- dependent kinase inhibitors such as p15INK4b and p21WAF1/CIP, which is needed for the cell-cycle arrest in terminal differentiation of neutrophils. Moreover, DAPK2 can bind and activate the key autophagy gene beclin-1 [169]. DAPK phosphorylates beclin 1 on Thr 119 located at a crucial position within its BH3 domain and thus promotes the dissociation of beclin 1 from BCL-XL inhibitor and induction of autophagy [169]. Here, beclin 1 was initially identified as a BCL-2- binding protein, which is part of a class III PI3K (phosphatidylinositol -3-kinase) multiprotein complex that participate in autophagosome nucleation. Death- associated protein kinase (DAPK1) is a calcium/ calmodulin (CaM) serine/threonine kinase for mediator of cell death [170]. PU.1, an ETS transcription factor known to regulate myeloid differentiation. Silencing of PU.1 in the adult hematopoietic tissue produces dysfunctional stem cells and impaires granulopoiesis by inducing a maturation block. Overexpression of PU.1 overcomes the differentiation block in SCa 1+/Lin- HSC with transduction of PML/ RARa fusion, as measured by the Gr-1 and Mac-1 expression [171]. Thus, pml/RARa represses PAPK2/PU.1 - mediated transcription of myeloid genes in APL,linking a novel autophagy mechanism of pml/ RARA degradation [172].

Figure 11:Molecular model of the gene regulation of retinoic acid (RA) action (George Zhu, January 1991, revised in 2012, further revised in 2018 and in this paper). Schematic alignment of the receptor protein. The two highly conserved regions, identified as the putative DNA-binding (C) and hormone- binding (E), a hinge region (D) and the non-conserved variable NH4-terminus (A/B) as described above. CAT:CAAT box, CCAAT-enhancer binding proteins(or C/EBPs); GC:GC box; TATA:TATA box. Note: In APLcells, pml/RARa fusion point is located in the first 60 amino acids from the N-terminus(A/B) of RARa [12,182].

The elucidation of the molecular basis of retinoic acid and retinoid pharmacology in APL has been illustrated in several publications [157,173-176] the detail molecular model of gene regulation had also been proposed by Zhu in 1990s [12,177,178]. As an approach to APL treatment, one possible the action of retinoic acid, A consensus sequence (TCAGGTCA motif) has been postulated for thyroid hormone (TRE) and retinoic acid responsive element(RARE)-containing in the promoter region of target genes [112]. High dose of RA-RARE-PML/RARa complexes in intracellular localization appears to relieve repressors from DNA-bound receptor [11,12,117,145,158,179] including the dissociation of corepressor complexes N-CoR, SMRT and HDACs from PML- RARa or partially PML-RARa/RXR [11,12,146,157,179]. Also release PML/RARa -mediated transcription repression [175]. This transcriptional derepression occurs at RARa target gene promoter [12,157,180]. Consquentially, PML-RARa chimera converted receptor from a repressor to a RA-dependent activator of transcription [156,157,160]. Co-activator complexes containing histone acetyltransferase (e.g. p300/CBP) are recruited. The resulting pml-RARA oncoprotein proteolytic degradation occurs through the autophagy- lysosome pathway [172] and the ubiquitin SUMO-proteasome system (UPS) [152-155] as well as caspase 3 [155] or lysosomal protease (cathepsin D) enzyme or/and EI-like ubiquitin-activating enzyme (UBEIL) induction [181]. An effect is to relieve the blockade of pml/RARa-mediated RA dependent promyelocytic differentiation and retinoic acid (9-cid RA, ATRA, Am80) in APL therapy Zhu G, March 1990- January 1991, revised in 2012). Here, RA can overcome the transcriptional repressor activity of pml/RARa [11,12,156,179,182]. The oncogenic pml/ RARa uncover a pathogenic role in leukemogenesis of APL through blocking promyelocytic differentiation. This oncogenic receptor derivative pml/RARa chimera is locked in their “off” regular mode thereby constitutively repressing transcription of target genes or key enzymes (such as AP-1, PTEN, DAPK2, UP.1, p21WAF/CCKN1A) [160-165] that are critical for differentiation of hematopoietic cells. This is first described in eukaryotes (Figure 11).

References

- Parker RO, Crouch RK (2010) Retinol dehydrogenases (RDHs) in the visual cycle. Exp Eye Res 91(6): 788-792.

- Rhinn M, Dolle P (2012) Retinoic acid signaling during development. Development 139(5): 843-858.

- DeMan J Principles of food chemistry (3rd edn). Aspen Publication Inc, Maryland, USA p. 358.

- Fridericia LS, Holm E (1925) Experimental contribution to the study of the relation between night blindness and malnutrition. Am J Physiol 73: 63-78.

- Yudkin AM (1931) The presence of vitamin A in the retina. Arch Ophthalmol 6(4): 510- 517.

- Wald G (1935) Vitamin A in eye tissues. J Gen Physiol 18(6): 905-915.

- Wald G (1935) Caroteniods and the visual cycle. J Gen Physiol 19: 351- 371.

- Wolf G (2001) The discovery of the visual function of vitamin A. The Journal of Nutrition 131(6): 1647-1650.

- Hashimoto Y, Kagechika H, Kawachi E, Shudo K (1988) Specific uptake of retinoids into human promyelocytic leukemia cells HL-60 by retinoidspecific binding protein, possibly the true retinoid receptor. Jpn J Cancer Res 79(4): 473-483.

- Shroot B (1990) Round table conference, Retinoic acid. Nour Rev Fr Hematol 32.

- Zhu G (2010) Use of chemotherapy and traditional chinese medicine for advanced cancer:A retrospective study of 68 patients(1993~2010). JCCM 5(6): 343-350.

- Zhu G, Mische SE, Seigneres B (2013) Novel treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia:As2O3, retinoic acid and retinoid pharmacology. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 14(9): 849-858.

- Sharma RP, Kim YW (1995) Localization of retinoic acid receptors in anterior human embryo. Experimental & Molecular Pathology(Exp Med Pathol) 62(3): 180-189.

- Paulsen DF (1994) Retinoic acid in limb-bud outgrowth:Review and hypothesis. Anat Embryol 190(5): 399-415.

- Maden M (1995) The role of retinoids in developmental mechanisms in embryos. Fat-Soluble Vitamins 30: 81-111.

- Frazier CN, Hu CK (1931) Cutaneous lesions associated with a deficiency in vitamin A in man. Arch Intern Med 48(3): 507-514.

- Nelson AM, Zhao W, Gilliland KL, Zaenglein AL, Liu W, et al. (2008) Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin mediates 13-cis retinoic acid-induced apoptosis of human sebaceous gland cells. The Journal of Chemical Investigation 118(4): 1468-1478.

- Cabezas-Wallscheid N, Buettner F, Sommerkamp P, Klimmeck D, Ladel L, et al. (2017) Vitamin A-retinoic acid signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell dormancy. Cell 169(5): 807-823.

- Fuchs E, Green H (1981) Regulation of terminal differentiation of cultured human keratinocytes by vitamin A. Cell 25(3): 617-625.

- Dour D, Koeffler HP (1982) Retinoic acid enhances growth of human early erythroid progenitor cells in vitro. J Clin Invest 69(4): 1039-1041.

- Lawrence HJ, Conner K, Keller MA, Haussler MR, Wallace P, et al. (1987) Cis-retinoic acid stimulates the clonal growth of some myeloid leukemia cells in vitro. Blood 69(1): 302-307.

- Chomienne C, Ballerini P, Balitrand N, Daniel MT, Fenaux P, et al. (1990) All-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia II. In vitro studies. Structure-function relationship. Blood 76(9): 1710-1717.

- Dour D, Koeffler HP (1982) Retinoic acid inhibition of the clonal growth of human myeloid leukemia cells. J Clin Invest 69(2): 277-283.

- Breitman TR, Selonic SE, Collins SJ (1980) Induction of differentiation of the human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60) by retinoic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77(5): 2936-2940.

- De Mendona Oliveira L, Emidio Teixeira FM, Notomi Sato M (2018) Impact of retinoic acid on immune cells and inflammatory diseases. Mediators Inflamm.

- Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank KB, Bouladoux N, Oukka M, et al. (2007) Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 Treg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med 204(8): 1775-1785.

- Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovskaya O, Scott I, et al. (2007) Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science 317(5835): 250-260.

- Visani G, Tosi P, Manfroi S, Ottaviani E, Finelli C, et al. (1995) Alltrans retinoic acid in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome. Leu lymphoma 19(3-4): 277-2780.

- Ohno R (1994) Differentiation therapy of myelodysplastic syndromes with retinoic acid. Leuk Lymphoma 14(5-6): 401-409.

- Maurer AB, Ganser A, Seipelt G, Ottmann OG, Mentzel U, et al. (1995) Changes in erythroid progenitor cell and accessary cell compartments in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes during treatment with alltrans retinoic acid and hematopoietic growth factors. Br J Haematol 89(3): 449-456.

- Itzykson R, Avari S, Vassilief D, Berger E, Slama B, et al. (2009) Is there a role for all-trans retinoic acid in combination with recombinant erythropoietin in myelodysplastic syndrome?A report on 59 cases. Leukemia 23(4): 673-678.

- Ferrero D, Darbesio A, Giai V, Genuardi M, Dellacasa CM, et al. (2009) Efficacy of a combination of human erythropoietin + 13-cis-retinoic acid and dihydroxylated vitamin D3 to improve moderate to severe anaemia in low/intermediate risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Br J Haematol 144(3): 342-349.

- Crisa E, Foli C, Passera R, Darbesio A, Garvey KB, et al. (2012) Long-term follow up of myelodysplastic sydrome patients with moderate/severe anaemia receiving human recombinant erythropoietin + 13-cis-retinoic acid and dihydroxylated vitamin D3:independent positive impact of erythroid response on survival. Br J Haematol 158(1): 99-107.

- Zhu G (2018) Long term follow up of patients with advanced cancers after chemotherapy and traditional medicine(82 cases). J Clin Trials Pathol Case Stud 3(1): 13- 21.Zhu G (2018) Long term follow up of patients with advanced cancers after chemotherapy and traditional medicine(82 cases). J Clin Trials Pathol Case Stud 3(1): 13- 21.

- Venditti A, Tamburini A, Buccisano F, Scimò MT, Del Poeta G, et al. (2000) A phase-II trial of all trans retinoic acid and low-dose cytosine arabinoside for the treatment of high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Ann Hematol 79(3): 138-1342.

- Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, et al. (1982) Proposals for the classification of the myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol 51(2): 189-199.

- Gottlicher M, Minucci S, Zhu P, Krämer OH, Schimpf A, et al. (2001) Valproic acid defines a novel class of HDAC inhibitors inducing differentiation of transformed cells. EMBO J 20(24): 6969-6978.

- Kuendgen A, Strupp C, Alvado M, Bernhardt A, Hildebrandt B, et al. (2004) Treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes with valproic acid alone or in combination with all-trans retinoic acid. Blood 104(5): 1266- 1269.

- Kuendgen A, Knipp S, Fox F, Strupp C, Hildebrandt B, et al. (2005) Results of a phase 2 study of valproic acid alone or in combination with all-trans retinoic acif in 75 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol 84(suppl 1): 61-66.

- Kuendgen A, Schmid M, Knipp S, et al. (2005) Valproic acid (VPA) achieves high response rates in patients with low-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 106 Abstract 789.

- Siitonen T, Timonen T, Juvonen E, Terävä V, Kutila A, et al. (2007) Valproic acid combined with 13-cis retinoic acid and 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in the treatment of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica 92(8): 1119-1122.

- Clamon G, Chabot GG, Valeriote F, Davilla E, Vogel C, et al. (1985) Phase I study and pharmacokinetics of weekly high dose 13-cis-retinoic acid. Cancer Res 45(4): 1874-1878.

- Koeffler HP (1986) Preleukemia. Clinics in Haematology, 15(3): 829- 850.

- Gold EJ, Mertelsmann RH, Itri LM, Gee T, Arlin Z, et al. (1983) Phase I clinical trial of 13-cis-retinoic acid in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Treatment Reports 67(11): 981-986.

- Greenberg BR, Durie BG, Barnett TC, Meyskens FL (1985) Phase I-II study of 13-cis-retinoic acid in myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer Treat Rep 69(12): 1369-1374.

- Piccozi VJ, Swanson GF, Morgan R, Hecht F, Greenberg PL (1986) 13-cisretinoic acid treatment for myelodysplastic syndromes. Journal of Clinical Oncology 4(4): 589-596.

- Besa EC, Hyzinskin NK, Abrahm JL (1985) High dose prolonged cisretinoic acid (RA) is required for clinical response in myelodysplastic syndrome(MDS). Blood 66(5): 663.

- Besa EC, Abrahm JL, Bartholomew MJ, Hyzinski M, Nowell PC (1990) Treatment with 13-cis-retinoic acid in transfusion-dependent patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and decreased toxicity with addition of alpha-tocopherol. Am J Med 89(6): 739-747.

- Besa EC, Kunselman S, Nowell PC (1998) A pilot trial of 13-cis-retinoic acid and alph-tocopherol with recombinant human erythropoietin in myelodysplastic syndrome patients with progressive or transfusiondependent anemias. The central pennsyvania Oncology Group. Leuk Res 22(8): 741-749.

- Abrahm J, Besa EC, Hyzinski M, Finan J, Nowell P, et al. (1986) Disappearance of cytogenetic abnormalities and clinical remission during therapy with 13-cis-retinoic acid in a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome:Inhition of growth of the patient’s malignant monocytoid clone. Blood 67(5): 1323-1327.

- Ho AD, Martin H, Knauf W, Reichardt P, Trümper L, et al. (1987) Combination of low-dose cytarabine and 13-cis retinoic acid in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res 11(11): 1041-1044.

- Aul C, Runde V, Gattermann N (1993) All-trans retinoic acid in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome:result of a pilot study. Blood 82(10): 2967-2974.

- Hofmann WK, Kell WJ, Fenaux P, Castaigne S, Ganser A, et al. (2000) Oral 9-cis retinoic acid(Alitretinoin) in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome:results from a pilot study. Leukemia 14(9): 1583-1588.

- Bourantas KL, Tsiara S, Christou L (1995) Treatment of 34 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes with 13-cis retinoic acid. Eur J Haematol 55(4): 235-239.

- Bollag W, Ott F (1975) Vitamin A acid in benign and malignant epithelial tumours of the skin. Acta Dermato-Venereol 74: 163.

- Kessler JF, Meyskens FL, Levine N, Lynch PJ, Jones SE (1983) Treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma(mycosis fungoides) with 13-cis-retinoic acid. The Lancet 1(8338): 1345-1347.

- Lippman SM, Meyskens FL (1987) Treatment of advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the skin with isotretinoin. Ann Intern Med 107(4): 499- 502.

- Beckenbach L, Baron JM, Merk HF, Loffler H, Amann PM (2015) Retinoid treatment of skin diseases. Eur J Dermatol 25(5): 384-391.

- Ward A, Brogden RN, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS (1984) Isotretinoin. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in acne and other skin disorders. Drugs 28(1): 6-37.

- Peck GL, Olsen TG, Yoder FW, Strauss JS, Downing DT, et al. (1979) Prolonged remission of cystic and conglobate acne with 13-cis-retinioc acid. N Engl J Med 300(7): 329-333.

- Farrell LN, Strauss JJ, Stranieri AM (1980) The treatment of severe cytstic acne with 13-cis-retinoic acid. J Am Acad Dermatol 3(6): 602-611.

- Jones DH, King K, Miller AJ, Cunliffe WJ (1983) A dose-response study of 13-cis-retinoic acid in acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 108(3): 333-343.

- Plewig G, Wagner A, Nikolowski J, et al. (1980) Treatment of severe acne, rosacea and gram negative folliculities with 13-cis-retinoic acid. Scientific Exhibit. Am Acad Dermatol.

- Rapini RR, Konecky EA, Schillinger B, Comite H, et al. (1983) Effect of varying dosages of isotretinoin on nodulocytic acne. J Invest Dermatol 80: 357.

- Goldstein JA, Socha-Szott A, Thomsen RJ, Pochi PE, Shalita AR, et al. (1982) Comparative effect of isotretinoin and etretinate on acne and sebaceous gland secretion. J Am Acad Dermatol 6(4 Pt 2 Suppl): 760- 765.

- Prendiville JS, Logan RA, Russell-Jones R (1988) A comparison of dapsone with 13-cis retinoic acid in the treatment of nodular cystic acne. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 13(2): 67-71.

- Landthaler M, Kammermehr J, Wagner A, Plewig G (1980) Inhibitory effects of 13-cis-retinoic acid on human sebaceous glands. Arch Dermatol Res 269(3): 297-309.

- King K, Jones DH, Daltrey DC, Cunliffe WJ (1982) A double-blind study of the effects of 13-cis-retinoic acid on acne, sebum excretion rate and microbial population. Br J Dermatol 107(5): 583-590.

- DeLuca L, Bonnani F, Bonanni F, Nelson D (1972) Manitenance of epithelial cell differentiation:the mode of actions of vitamin A. Cancer 30(5): 1326-1331.

- Fisher GL, Voorhees JJ (1996) Molecular mechanisms of retinoid actions in skin. FASEB J 10(9):00201002-1013.

- Dispenza MC, Wolpert EB, Gilliland KL, Dai JP, Cong Z, et al. (2012) Systemic isotretinoin therapy normalizes exaggerated TLR2-mediated innate immune responses in acne patients. J Invest Dermatol 132(9): 2198-2205.

- Nikolowski J, Plewig G (1981) Oral treatment of rosacea with 13-cisretinoic acid. Hautarzt 32(11): 575-584.

- Goldsmith LA, Weinrich AE, Shupack J (1982) Pityriasis rubra pilasis response to 13-cis-retinoic acid(Isotretinoin). J Am Acad Dermatol 6(4 Pt 2 Suppl): 710-715.

- Skroza N, Proietti I, Tolino E, Bernardini N, La Viola G, et al. (2014) Isotretinoin for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma arising on an epidermoid cyst. Dermatol Ther 27(2): 94-96.

- Sankowski A, Janik P, Bogacka-Zatorska E (1984) Treatment of basal cell carcinoma with 13-cis-retinoic acid. Neoplasma 31(5): 615-618.

- Yung WK, Kyritsis AP, Gleason MJ, Levin VA (1996) Treatment of recurrent malignant gliomas with high-dose 13-cis retinoic acid. Clin Cancer Res 2(12): 1931-1935.

- Roach M (1983) A malignant eccrine poroma responds to isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid). Ann Intern Med 99(4): 486-488.

- Haydey RP, Reed ML, Shupak JL, Dzubow LM (1980) Treatment of keratoacanthomas with oral 13-cis-retinoic acid. N Engl J Med 303(10): 560-562.

- Levine N, Miller RC, Meyskens FL (1984) Oral isotretinoin therapy. Use in patient with multiple cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas and keratoacanthomas. Arch Dermatol 120(9): 1215-1217.

- Zaman S, Gillani JA, Khattak R, Khattak R, Iqbal, et al. (2014) Role of isotretinoin in cancer prevention and management in malignancies associated with xeroderma pigmentosum. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 26(2): 255-257.

- Kamata N, Chida K, Rikimaruk, Horikoshi M, Enomoto S, et al. (1986) Growth-inhibitory effects of epidermal growth factor and overexpression of its receptors on human squamous cell carcinomas in culture. Cancer Res 46(4 Pt 1): 1648-1653.

- Tang CK, Gang XQ, Maseatello DK, Wong AJ, Lippman MF (2000) Epidermal growth factor VIII enhances tumorigenicity in human breast cancer. Cancer Res 60(11): 3081-3087.

- Stutz MA, Shattuck DL, Laederich MB, Carraway III KL, Sweeney C, et al. (2008) LRIG1 negatively regulates the oncogenic EGF receptor mutant EGFRvIII. Oncogene 27(43): 5741-5752.

- Yan T, Mizutani A, Chen L, Takaki M, Hiramoto Y, et al. (2014) Characterization of cancer stem-like cells derived from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells transformed by tumor-derived extracellular vesicles. J Cancer 5(7): 572-584.

- Montermini L, Meehan B, Garnier D, Lee WG, Lee TH, et al. (2015) Inhibition of oncogenic epidermal growth factor receptor kinase triggers release of exosome-like extracellular vesicle and impacts their phosphoprotein and DNA content. J Biol Chem 290(40): 24534-24546.

- Lee JC, Vivanco I, Beroukhim R, Rameen Beroukhim, Huang JH, et al. (2006) Epidermal growth factor receptor activation in glioblastoma through novel missense mutations in the extracellular domain. PLoS Med 3(12): e485.

- Wang LK, Hsiao TH, Hong TM, Chen HY, Kao SH, et al. (2014) MicroRNA- 133a supresses multiple oncogenic membrane receptors and cell invasion in non-small cell lung carcinoma. PLoS one 9(5): e96765.

- Zhu G, Saboor-Yaraghi AA, Yarden Y, Santos J, Neil JC (2016) Downregulating oncogenic receptor: From bench to clinic. Hematol Med Oncol 1(1): 30-40.

- Greulich H, Chen TH, Feng W, Janne PA, Alvarez JV, et al. (2005) Oncogenic transformation by inhibitor-sensitive and -resistant EGFR mutants. PLoS Med 2(11): e313.

- Zhu G (2018) Treatment of patients with advanced cancer following chemotherapy and traditional medicine - Long term follow up of 75 cases. Universal Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 3(3): 10-18.

- Gansdola M (1984) Therapy of severe acne and acne rosacea with oral 13-cis-retinoic acid (Isotretinoin). Acta Vitaminol Enzymol 6(4): 325- 337.

- Leyden JJ, McGinley KJ (1982) Effects of 13-cis-retinoic acid on sebum production and propionibacterium acnes in severe nodulocystic acne. Arch Dermatol Res 272(3-4): 331-337.

- Hennes R, Mack A, Schell H, Vogt HJ (1984) 13-cis-retinoic acid in conglobate acne. A follow-up study of 14 trial centers. Arch Dermatol Res 276(4): 209-215.

- Pigatto PD, Fioroni A, Moroni P (1983) Effects of 13-cis-retinoic acid (Ro4-3780) in the therapy of severe cystic acne. Acta Vitaminol Enzymol 5(1): 23-28.

- Ott F, Geiger JM (1982) Long-term treatment of severe nodulo-cystic acne with 13-cis retinoic acid. Ann Dermatol Venereol 109(10): 849- 853.

- Bouriez D, Giraud J, Gronnier C, Varon C (2018) Efficiency of all-trans retinoic acid on gastric cancer: A narrative literature Review. Int J Med Sci 19(11): E3388.

- Evans RM (1988) The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science 240(4854): 889-895.

- Giguere V, Ong ES, Segui P, Evans RM (1987) Identification of a receptor for morphogen retinoic acid. Nature 330(6149): 624-629.

- Petkovich M, Brand N, Krust A, Chambon P (1987) A human retinoic acid receptors which belongs to the family of nuclear receptors. Nature 330(6147): 444-450.

- Brand N, Petkovich M, Krust A, Chambon P, de The H, et al. (1988) Identification of a second human retinoic acid receptor. Nature 332(6167): 850-853.

- Krust A, Kastner PH, Petkovich M, Zelent A, Chambon P, et al. (1989) A third human retinoic acid receptor, hRAR- gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86(14): 5310-5314.

- Lehmann JM, Hoffmann B, Pfahl M (1991) Genomic organization of the retinoic acid receptor gamma gene. Nucleic Acids Res 19(3): 573-578.

- Beato M (1989) Gene regulation by steroid hormone. Cell 56(3): 335- 344.

- Chalepakis G, Postma JPM, Beato M (1988) A model for hormone receptor binding to the mouse mammary tumour virus regulatory element based on hydroxyl radical footprinting. Nucl Acids Res 16(21): 10237-10247.

- Chiocca EA, Davies PJA, Stein JP (1986) The molecular basis of retinoic acid action. Transcriptional regulation of tissue transglutaminase gene expression in macrophages. J Biol Chem 263(23): 11584-11589.

- Schule R, Evans RM, Rangarajan P, Yang N, Kliewer S, et al. (1991) Retinoic acid is a negative regulator of AP-1-responsive genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88(14): 6092-6096.

- Lehman JM, Jong L, Fanjul A, Cameron JF, Lu XP, et al. (1992) Retinoids selective for retinoid X receptor response pathways. Science, 258(5090): 1944-1946.

- Hauksdotti H, Privalsky ML (2001) DNA recognition by the aberrant retinoic acid receptors implicated in human acute promyelocyric leukemia. Cell Growth Differ 12(2): 85-98.

- Schr der M, Wyss A, Sturzenbecker LJ, J F Grippo, P LeMotte, et al. (1993) RXR-dependent and RXR-independent transactivation by retinoic acid receptors. Nucleic Acids Res 21(5): 1231-1237

- Horlein AJ, Naar AM, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Gloss B, et al. (1995) ligandindependent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature 377(6548): 397-404.

- Chen JD, Evans RM (1995) A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 3779(6548): 454-457.

- Umesono K, Giguere V, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Evans RM, et al. (1988) Retinoic acid and thyroid hormone induce gene expression through a common responsive element. Nature 336(6196): 262-265.

- Balmer JE, Blomhoff R (2005) A robust characterization of retinoic acid response elements based on a comparison of sites in three species. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 96(5): 347-354.

- Mitchell PJ, Tjian R (1989) Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Science 245(4916): 371-378.

- Dilworth FJ, Chambon P (2001) Nuclear receptors coordinate the activation of chromatin remodeling complexes and coactivators to facilitate initiation of transcription. Oncogene 20(24): 3047-3054.

- Beckenbach L, Baron JM, Merk HF, Loffler H, Amann PM, et al. (2015) Retinoid treatment of skin diseases. Eur J Dermatol 25(5): 384-391.

- Damm K, Thompson CC, Evans RM (1989) Protein encoded by v-erbA functions as a thyroid-hormone receptor antagonist. Nature 339: 593- 597.

- Graupner G, Wills KN, Tzukerman M, Zhang XK, Evans EM, et al. (1989) Dual regulatory role for thyroid-hormone receptors allows control of retinoic-acid receptor activity. Nature 340(6235): 653-656.

- Evans PD, Jaseja M, Jeeves M, Hyde EI (1996) NMR studies of the Escheerichia Coli Trp repressor.trpRs operator complex. Eur J Biochem 242(3): 567-575.

- Lazar MA (2003) Nuclear receptor corepressors. Nucl Recept Signal 1: e001.

- Kornberg RD (1999) Eukaryotic transcriptional control. Trends Cell Biol 9(12): M46-49.

- Onate SA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW (1995) Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor family. Science 270(5240): 1354-1357.

- Walkley CR, Yuan YD, Chandraratna RAS, McArthur GA (2002) Retinoic acid receptor antagonism in vivo expands the numbers of precursor cells during granulopoiesis. Leukemia 16(9): 1763-1772.

- Tallman MS, Altman JK (2009) How I treat acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 114(25): 5126-5135.

- Flynn TJ, Miller WJ, Weisdorf DJ, Arthur DC, Brunning R, et al. (1983) Retinoic acid treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia: in vitro and in vivo observation. Blood 62(6): 1211-1217.

- Castaigne S, Chomienne C, Daniel MT, Ballerini P, Berger R, et al. (1990) All-trans-retinoic acid as a differentiation therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia. I. clinical results. Blood 76(9): 1704-9.

- Tobita T, Takashita A, Kitamura K, et al. (1997) Treatment with a new synthetic retinoid, Am80, of acute promyelocytic leukemia relapsed from complete remission induced by all-trans retinoic acid. Blood 90(3): 967-973.

- Soignet SL, Benedetti F, Fleischauer A, Ohnishi K, Yanagi M, et al. (1998) Clinical study of 9-cis retinoic acid (LGD 1057) in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia 12(10): 1518-1521.

- Au WY, Kumana CR, Lee HKK, Lee HK, Lin SY, Liu H, et al. (2011) Oral arsenic trioxide-based maintenance regimens for first complete remission of acute promyelocytic leukemia. a 10-year follow-up study. Blood 118(25): 6535-6543.

- Ades L, Guerci A, Raffoux E, Sanz M, Chevallier P, et al. (2010) Very long-term outcome of acute promyelocytic leukemia after treatment with all-trans retinoic acid and chemotherapy, the European APL group experience. Blood 115(9): 1690-1696.

- Asou N (2017) Retinoic acid, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and Tamibarotene. Chemotherapy for Leukemia 131: 183-211.

- Cicconi L, Lo-coco F, (2016) Current management of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Ann Oncol 27(8): 1474-81.

- de The H, Chomienne C, Lanotte M, Degos L, Dejean A (1990) The t(15;17) translocation of acute promyelocytic leukemia fuses the retinoic acid receptor a gene to a novel transcribed locus. Nature 347(6293): 558-561.

- Alcalay M, Zangrilli O, Pandolfi PA, Longo L, Mencarelli A, et al. (1991) Translocation breakpoint of acute promyelocytic leukemia lies within the retinoic acid receptor alpha gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88(5): 1977-1978.

- Kakizuka A, Miller WH, Umesono K, Warrell RP, Frankel SR, et al. (1991) Chromosomal translocation t(15;17) in human acute promyelocytic leukemia fuses RARa with a novel putative transcription factor, PML. Cell 66(4): 663-674.

- Zhu Y (1992) Retinoic acid receptor alpha gene rearrangement as specific marker of acute promyelocytic leukemia and its use in the study of cell differentiation. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 72(4): 229-233.

- Zhu G (1992) Oncogenic receptor hypothesis (1989-91). VOA (Voice of America) 12: 31.

- Marinelli A, Bossi D, Pellicci PG, Minucci S (2007) A redundant oncogenic potential of the retinoic acid receptor(RAR) alpha, beta and gamma isoforms in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia 21(4): 647-650.

- Segalla S, Rinaldi L, Kalstrup-Nielsen C (2003) Retinoic acid receptor alpha fusion to PML affects its transcriptional and chromatinremodeling properties. Mol Cell Biol 23(23): 8795-8808.

- Osumi T, Tsujimoto SI, Tamura M (2018) Recurrent RARBtranslocations in acute promyelocytic leukemia lacking RARA translocation. Cancer Res 78(16): 4452-4458.

- Such E, Cervera J, Valencia A (2011) A novel NUP98/RSRG fusion in acute myeloid leukemia resembling acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 117(1): 242-245.

- Ha JS, Do YR, Ki CS, Jeon DS, Kim DH, et al. (2017) Identification of a novel PML-RARG fusion in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia 31(9): 1992-1995.

- Tsai S, Collins SJ (1993) A dominant negative retinoic acid receptor blocks neutrophil differentiation at promyelocytic stages. PNAS 90(15): 7153-7157.

- Onodera M, Kunisada T, Nishikawa S, Sakiyama Y, Matsumoto S, etal. (1995) Overexpression of retinoic acid receptor alpha suppresses myeloid cell differentiation at the promyelocyte stage. Oncogene11(7): 1291-1298.

- Grignani F, Testa U, Rogaia D, Ferrucci PF, Samoggia P, et al. (1996) Effects on differentiation by the promyelocytic leukemia pml/RAR alpha protein dimerization and RARalpha DNA binding domains. EMBO J 15(18): 4949-4958.

- Grignani F, De Matteis S, Nervi C, Tomassoni L, Pelicci PG, et al. (1998) Fusion proteins of the retinoic acid receptor-a recruit histone deacetylase in promyelocytic leukemia. Nature 391(6669): 815-818.

- Carbone R, Botrugn OA, Ronzoni S, Insinga A, Pelicci PG, et al. (2006) Recruitment of the histone methyltransferase SUV39H1 and its role in the oncogenic properties of the leukemia-associated PML-retinoic acid receptor fusion protein. Mol Cell Biol 26(4): 1288-1296.

- Brown D, Kogan S, Lagasse E, Weissman L, Alcalay M, et al. (1997) A PML/RARa transgenic initiates murine acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94(6): 2551.

- He LZ, Tribioli C, Rivi R, Peruzzi D, Pelicci PG, et al. (1997) Acute leukemia with promyelocytic features in pml/RARa transgenic mice. Blood 94(10): 5302-5307.

- Westervelt P, Lane AA, Pollock JL, Oldfather K, Holt MS, et al. (2002) High penetrance mouse model of acute promyelocytic leukemia with very low levels of PML-RAR alpha expression. Blood 102(5): 1857- 1865.

- Rousselot P, Hardas B, Patel A, Guidez F, Gäken J, et al. (1994) The PMLRARa gene products of the t (15;17) translocation inhibits retinoic acidinduced granulocytic differentiation and mediated transactivation in human myeloid cells. Oncogene 9(2): 545-551.

- Raelson JV, Nervi C, Rosenauer A, Benedetti L, Monczak Y, et al. (1996) The PML/RAR alpha oncoprotein is a direct molecular target of retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Blood 88(8): 2826-2832.

- Yoshida H, Kitamura K, Tanaka K, Omura S, Miyazaki T, et al. (1996) Accelerated degradation of PML-RARA oncoprotein by ATRA in APL:possible role of the proteasome pathway. Cancer Res 56(13): 2945-2948.

- Fanelli M, Minucci S, Gelmetti V, Nervi C, Pelicci PG (1999) Constitutive degradation of pml/RAR through the proteasome pathway mediates retinoic acid resistance. Blood 93(5): 1477-1481.

- Nervi C, Ferrara FF, Fanelli M, Rippo RM, Tomassini B, et al. (1998) Caspases mediate retinoic acid-induced degradation of the acute promyelocytic leukemia PML/RARa fusion protein. Blood 92(7): 2244- 2251.

- Jing Y, Xia L, Lu M, Waxman S (2003) The cleavage product delta PMLRARa contributes to all-trans retinoic acid-mediated differentiation in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Oncogene 22(26): 4083-4091.

- Tomita A, Kiyoi H, Naoe T (2013) Mechanisms of action and resistance to all-trans retinoic acid(ATRA) and arsenic trioxide(As2O3) in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Int J Hematol 97(6): 717-725.

- Rosenauer A, Raelson JV, Nervi C, Eydoux P, DeBlasio A, et al. (1996) Alterations in expression, binding to ligand and DNA, and transcriptional activity of rearranged and wild-type retinoid receptors in retinoid-resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia cell lines. Blood 88(7): 2671-2682.

- Bellodi C, Kindle K, Bernassola F, Binsdale D, Cossarizza A, et al. (2006) Cytoplasmic function of mutant promyelocytic leukemia (PML) and PML-retinoic acid receptor alpha. J Biol Chem 281(20): 14465-14473.

- Doucar V, Brockes JP, Yaniv M, de The H, Dejean A, et al. (1993) The PML-retinoic acid alpha translocation converts the receptor from an inhibitor to a retinoic acid-dependent activator of transcription factor AP-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90(20): 9345-9349.

- Park DJ, Chumakov AM, Vuong PT, Chih DY, Koeffler HP, et al. (1999) CCAAT/enhancer binding protein epsilon is a potential retinoid target gene in acute promyelocytic leukemia treatment. J Clin Invest 103(10): 1399-1408.

- Yamanaka R, Barlow C, Lekstrom-Himes J, Castilla LH, Liu PP, et al. (1998) Impaired granulopoiesis, myelodysplasia, and early lethality in CCAAT/enhancer binding protein epsilon-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94(24): 13187-13192.

- Humbert M, Federzoni EA, Britschgi A, Valk PJ, Kaufmann T, et al. (2014) The tumor suppressor gene DAPK2 is induced by the myeloid transcript factors PU.1 and C/EBPa during granulocytic differentiation but repressed by PML-RARa in APL. J Leuk Biol 95(1): 83-93.

- Noguera NI, Piredda ML, Taulli R, Catalano G, Angelini G, et al. (2016) PML/RARa inhibits PTEN expression in hematopoietic cells by competing with PU.1 transcriptional activity. Oncotarget 7(41): 66386-66397.

- Choi W-II, Yoon JH, Kim MY, Koh DI, Litch JD, et al. (2014) Promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger-retinoic acid receptor a(PLZF-RARa), an oncogenic transcriptional repressor of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A(p21WAF/CCKN1A) and tumor protein p53(TP53) gene. J Biol Chem 289(27): 18641-18656.

- Zhang J, Grindley JC, Yin T, Jayasinghe S, Ross JT, et al. (2006) PTEN maintains hematopoietic stem cells and acts in lineage choice and leukemia prevention. Nature 441(7092): 518-522.

- Yilmaz QH, Valdez R, Theisen BK, Guo W, Feruson DO, et al. (2006) Pten dependence distinguishes haematopoietic stem cells from leukemiainitiating cells. Nature 441(7092): 475-482.

- Mueller BU, Pabst T, Fos J, Petkovic V, Asou N (2006) ATRA resolves the differentiation block in (15;17) acute promyelocytic leukemia by restoring PU.1 expression. Blood 107(8): 3330-3338.

- Zalckvar E, Berssi H, Mizrachy L, Idelchuk Y, Koren I, et al. (2009) DAPkinase mediated phosphorylation on the BH3 domain of beclin 1 from BCL-XL and induction of autophagy. EMBO Rep 10(3): 285-292.

- Cohen O, Feinstein E, Kimchi A (1997) DAP-kinase is a Ca2+/ calmodulin-dependent, cytoskeletal-associated protein kinase, with cell death-inducing functions that depends on its catalytic activity. EMBO J 16(5): 998-1008.

- Seshire A, Iger TR, French M, Beez S, Hagemeyer H (2012) Direct interaction of PU.1 with oncogenic transcription factors reduces its serine phosphorylation and promoter binding. Leukemia 26(6): 1338- 1347.

- Isakson P, Bjoras M, Boe SO, Simonsen A (2010) Autophagy contributes to therapy-induced degradation of the PML/RARA oncoprotein. Blood 116(13): 2324-2331.

- Melnick A, Litcht JD (1999) Deconstructing a disease, RAR, its fusion partners, and their roles in the pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 93(10): 3167-3215.

- Marstrand TT, Borup R, Willer A, Borregaad N, Sandelin A, et al. (2010) A conceptual framework for the identification of candidate drugs and drug targets in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia 24(7): 1265- 1275.

- Lallemand BV, de The H (2010) A new oncoprotein catabolism pathway. Blood 116(13): 2200-2201.

- Dos Santos GA, Kats L, Pandolfi PP (2013) Synergy against PML-RARa targeting transcription, proteolysis, differentiation, and self-renewal in acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Exp Med 210(13): 2793-2802.

- Zhu G (2014) Discovery of the molecular basis of retinoic acid action (retinoid signaling)- A genetic regulation of eukaryotes in transcription(Abstract). Proceedings of 3nd biotechnology world congress 97-98.

- Zhu G, Saboor-Yaraghi AA, Yarden Y (2017) Targeting oncogenic receptor:From molecular physiology to currently the standard of target therapy. Advance Pharmaceutical Journal 2(1): 10-28.

- He LZ, Guidez F, Tribioli C, Peruzzi D, Pandolfi PP, et al. (1998) Distinct interactions of PML-RARa and PLZF-RARa with Co-repressors determine differential responses to RA in APL. Nature Genetics 18(2): 126-135.

- Villa R, Morey L, Raker VA, Burchbeck M, Gutierrez A, et al. (2006) The methyl-CpG binding protein MBD, is required for PML-RARa fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103(5): 1400-1405.

- Kitareewan S, Pitha-Rowe I, Sekula D, Lowrey CH, Nemeth MJ, et al. (2002) UBE1L is a retinoid target that triggers PML/RAR alpha degradation and apoptosis in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99(6): 3806-3811.

- Zhu G, Ahmed Al-Kaf AG (2018) Vitamin A, retinoic acid and tamibarotene, a front toward its advances:a review. Univ J Pharm Res 3(6): 38-48.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.