Research Article

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Discriminating Bangladeshi Children and Adolescents of Affluent Families by Level of Obesity

*Corresponding author: KC Bhuyan, Ex Professor of Statistics, Jahangirnagar University, Bangladesh.

Received: July 20, 2019; Published: August 06, 2019

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.04.000810

Abstract

The present analysis was based on data regarding level of obesity of 662 children and adolescents of 560 families of students of American International University, Bangladesh. The children and adolescents were classified by level of obesity, where level of obesity was measured by percentiles of BMI. It was observed that, among 662 children and youth 465 were in underweight group. Obesity and severe obesity were observed among 9.1 percent children and adolescents. Among the obese and severe obesity group, 53% killed their time by watching television and another 26.7% spent their time by doing other works including games and sports. Obesity and severe obesity were associated with time spent by the children and adolescents. Among these groups 31.7% were suffering from diabetes. Diabetes and level of obesity were significantly associated. Among obese and severe obese group around 42% were habituated in taking restaurant food and these two characters were also significantly associated. Some socioeconomic factors of parents were also associated with level of obesity. The discriminant analysis showed that the children and adolescents of different levels of obesity were significantly different mainly for parents’ education and fathers’ occupation.

Keywords: Obesity; Severe obesity; Prevalence of diabetes; Association of level of obesity; Discriminant analysis

Introduction

Child obesity is a condition where excess body fat negatively affects a child’s health or well-being and creates a state of chronic calorie imbalance [1]. Trends in obesity are causing serious public health problem throughout the world [2]. It is a threat to the viability of basic health care delivery. It is an independent risk factor for many non-communicable diseases like diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, cardiovascular disease risk, osteoarthritis and cancer. A global epidemic of pediatric obesity occurred in recent years, and prevalence of obesity is continuing to rise [3]. In the developed world obesity is now the most common disease of childhood and adolescence. In Bangladesh also, the increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity among children (0-12 years) and adolescents (13-19years) have emerged as a major public health problem [4] and it was observed that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents varied from 1.0% to 20.6% and 0.35 to 25.6%, respectively. The pooled prevalence rates of overweight and obesity were 7.0% and 6.0%, respectively. However, it is in increasing trend. Approximately, 43 million pre-school age children throughout the world have been estimated to be overweight and obese and 92 million are at risk of overweight [5].

Children who are obese are at a significantly elevated risk for adverse health outcomes including both medical and psychological problems [6]. The most common medical co-morbidities associated with obesity include metabolic risk factors for type ІІ diabetes (T2D) including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, impaired glucose tolerance and metabolic syndrome [7,8]. Behavioral factors have significant effects on metabolic risk. It has been observed in some research findings that youth who do not meet guidelines for dietary behavior, physical activity and sedentary behavior have greater insulin resistance than those who do meet guidelines [9].

Psychological correlates of obesity create problems both in the family and in the society. The problems include reduced quality of life, low self-esteem social isolation and discrimination [10-12]. Depressed mood has been associated with greater risk of obesity and higher BMI [13]. The short and long term medical and psychological effects of childhood obesity have adverse consequences including increased morbidities and early mortality in adulthood [11,13].

A prospective study on adolescents revealed that as young adults, women particularly had an increased risk of social and economic difficulties [14]. Obesity has been attributed to various factors including genetics, environment, metabolism, behavior, personal history of obesity, culture and socio-economic status [9]. The origins of obesity can be traced to early adiposity rebound, which refers to the time at which BMI of young children begins to increase after reaching their lowest level of fat. Children in whom adiposity rebound begins at age of three years tend to have an increased mean BMI from age 3 to adolescence, which often extends into adulthood [14,15]. Children born to overweight or obese mothers are more likely to be overweight by the age of four years old even if their BMI is within the average range at the age of two years [16]. Other aspects of family environment are also highly influential [1]. Parents’ knowledge about nutrition and physical activity have also been found to be very strong predictors of children’s weight status [17]. In a study [18], among school-aged children it was observed that parental behavior and BMI have stronger impact on children’s BMI. Features of the built environment, including excess to parks, supermarkets, and convenient store hours, have been found to moderate treatment effects of obesity intervention [19].

Proximity of a person’s home to fast food restaurants has been associated with increased obesity rates [20]. Living in low-income neighborhoods has also been associated with more sedentary behavior and less physical activity [21]. School activity affects physical activity in youth. It has observed that children in higher socioeconomic schools have more excess to regular physical education classes than children attending low socioeconomic schools [22]. Therefore, it can be concluded that environmental factors are associated with physical activity and indirectly are associated with overweight and obesity. Beside, family and school based interventions, medical treatment, etc. can prevent overweight and obesity among children and youth and ultimately the disease like diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, cardiovascular disease risk, osteoarthritis and cancer.

Considering all the associations of childhood obesity as discussed above, the objective of the present study was to identify the socioeconomic factors associated with overweight and obesity among children and youth under the age of 18 years who belonged to privileged families. The specific objectives were:

i) to estimate the proportions of overweight and obese groups of children and youth,

ii) to identify the factors associated with overweight and obesity of children and youth and to test the significance of the associations.

iii) to discriminate the children and youth according to the level of obesity and to identify the factors responsible for the discrimination.

Methodology

The present analysis was based on 662 responses observed from 560 randomly selected affluent [23,24] families of students of American International University - Bangladesh during Summer 2016-2017 semester. During the semester there were 9488 students in the university. One of our objectives was to estimate the proportions of children and youth of different levels of obesity along with a combined proportion of obese and severe obese group of all ages of children and youth. In a previous study [4] it was reported that there were 7% overweight and obese children and youth in Bangladesh. Accordingly, we had decided to have a proportion of at least 7% overweight and obese children and youth with margin of error of 2% with 95% confidence in our study. To have such an estimate it required a sample of students of size n, where n= 625 proportion of expected obese and overweight children and youth, p = 0.07, q =0.93, margin of error, d =0.02, normal ordinate for 95% confidence, z= 1.96. These values were used to calculate the value of n]. This sample size covered 6.6% students of the university. The sample students were selected by simple random sampling method and were expecting at least responses from 5% families of the students. However, information was received from 560 families, covering the data of 662 children.

The data were collected through pre-designed and pre-tested printed questionnaire covering the questions related to the demographic characteristics of the children and youth of age below 18 years and the questions related to the socioeconomic variables of the parents. The randomly selected students were given written instructions how to collect information and they were requested to help in collecting information from their parents, who were very much concerned about the health hazard of their offspring. The children’s fathers/mothers filled in the questionnaires as the they were under 18 years of age and some were even below 10 years. The important collected information was age, height, weight, sex, food habit, time spent, involvement in co-curricular activities, if it is feasible, of the children. To study the socioeconomic background of the children the information regarding parent’s level of education, occupation and income were also collected. For youth having diabetes, the latest blood sugar level measured by registered practitioner or measured in a registered clinic also recorded. Association of level of obesity of offspring with families’ socioeconomic background were examined using chi-square test, where significant association was concluded when p-value ≤0.05. To study the socioeconomic background of the children the information regarding parent’s level of education, occupation and income were also collected. For youth having diabetes, the latest blood sugar level measured by registered practitioner or measured in a registered clinic also recorded.

Discriminant analysis was performed to discriminate the children and youth by their level of obesity. This analysis gave an idea about the importance of the variables in discriminating [23,24] the children and youth by their level of obesity. The variables used in discriminant analysis were age of children and youth, their food habit, spending of time, parent’s education, parent’s occupation, and monthly family income. Some of the variables were qualitative in character. These variables were transformed to nominal scale by assigning number.

Result

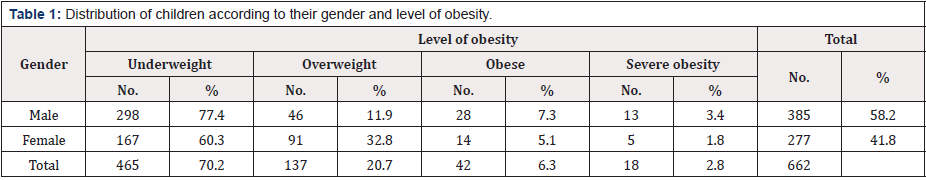

The data of the present analysis included different social, medical and economic aspects of 662 children aged 18years or below of 560 randomly selected families of students of American International University- Bangladesh. Amongst the studied children 58.2% were males and 41.8% were females. The children and youth were classified by their gender and level of obesity. The level of obesity was decided by the level body mass index (BMI kg/ m2). As methods of direct determination of body fat is difficult, the diagnosis of obesity is often based on body mass index [BMI]. Among the children aged 2-19 years the obesity is measured by BMI<5-th percentile=underweight, BMI is between 85th to 95th percentile= overweight, BMI >95th percentile is obese and BMI 120% of 95th percentile= severe obesity [3]. For all the children and youth, the mean BMI was 17.67 with a standard deviation 10.58. The underweight group of children and adolescents had BMI<23 kg/ m2. The BMI for other 3 groups were 23-<30, 30-<45 and 45+. The BMI values were decided according to the percentile’s values. The classified results were shown in (Table 1). Obese and severe group of children and adolescents were 9.1%. This finding is almost like that observed in another study [4]. It was seen that among the male children 77.4 percent were underweight. The corresponding figure among females is 60.3 percent. The differential in obesity by gender were significant [χ2= 44.03, p-value= 0.00].

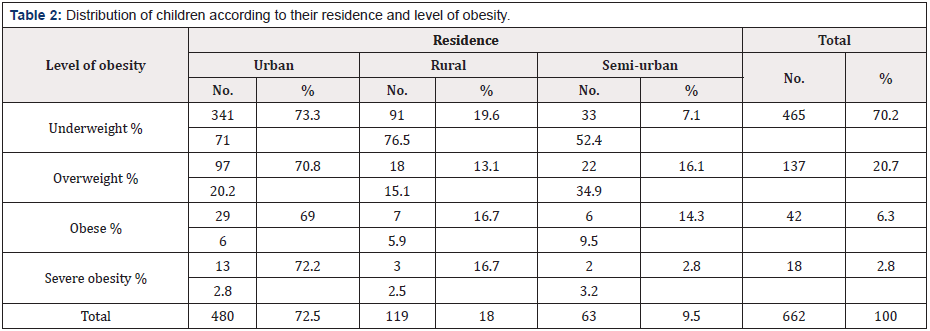

The information of 72.5% children were reported from urban area. The corresponding percentages of rural and semi-urban children were 18 and 9.5, respectively. The classified information of number of children of different levels of obesity belonging to different residential areas are presented in s 2. It was seen that maximum village children (76.5%) were underweight compared to urban and semi-urban children. Again, among the village children, number of obese and severe obese groups were lower compared to other groups of children. The differences in proportions of level of obesity and residence of children were significantly different [χ2= 12.45, p-value= 0.04].

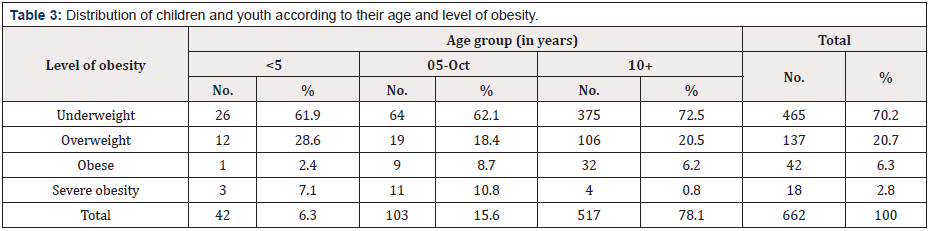

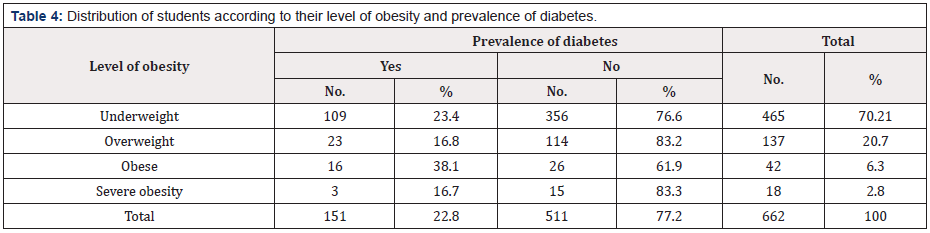

The investigated children and youths were classified into three classes by their age levels. These three groups of children were again classified by their level of obesity. The classified results are shown in Table 3. It was seen that 72.5% children and youths of age group 10 years and above were underweight. The proportions of underweight children of other two groups were lesser than the percentages of overall underweight group of children. The higher percentage of overweight group was observed among the children of age less than 5 years. This differential in proportions of level of obesity according to age groups was highly significant as calculated χ2= 38.94 with p-value = 0.00. Amongst the investigated children and youth 22.8% were diabetic (Table 3). The corresponding percentage among obese and severe obese group together is 31.7%. Diabetes was less prevalent among overweight group (16.8%). The differences in proportions of diabetic group among children with different levels of obesity were significant [χ2= 8.75 with p-value = 0.033].

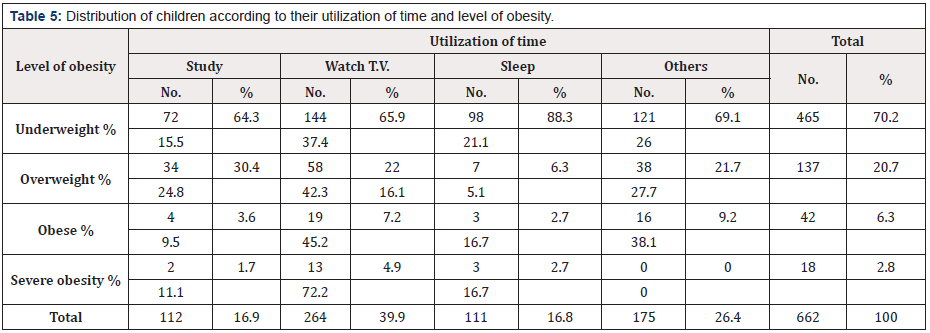

The present study group of children were mostly living in city center (72.5%) and they had enough scope to be involved in physical activity like games and sports. Still majority of the children (39.9%) spent their time by watching television and 16.8% slept after or before their academic activities. One-fourth (26.4%) of the investigated children mentioned that they were involved in some other activities including games and sports [Table 5]. Around 72% severe obese group killed their time by watching television. The corresponding percentage among obese group was 45.2%. The differences in proportions of utilization of time by the children of different obese groups were significantly different as [χ2= 54.12 with p-value = 0.00].

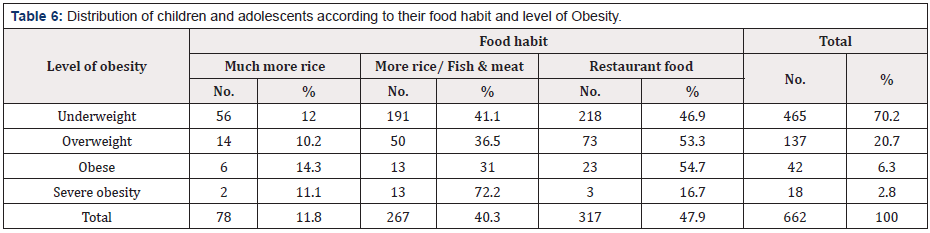

Table 6: Distribution of children and adolescents according to their food habit and level of Obesity.

Let us now observe the food habits of investigated children and adolescent. As the investigating units were mostly from affluent residents of city, they had the scope to get enough foods, with proper hygienic measures. Among the investigating units 47.9% [Table 6] were habituated in taking food from restaurants. Among the obese children 54.7% were habituated in taking restaurant food. Of course, higher proportions of underweight (46.9%) and overweight group of children (53.3%) were habituated in taking restaurant food. However, the differentials in proportions of children taking restaurant food according to different levels of obesity were significant [χ2= 94.63 with p-value= 0.00].

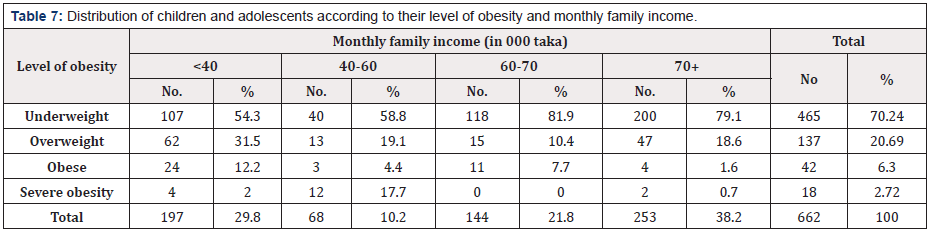

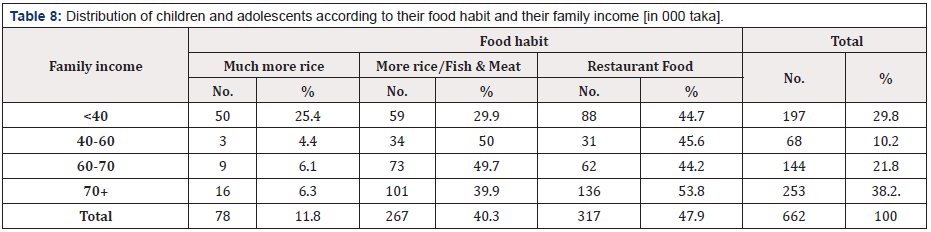

Usually the children of affluent families were more prone to be stay back in the house and kill time by watching television and they had more chances to frequently visit fast food shops. Their parents could afford the cost of fast food and they also fulfilled the demand of their children if they had enough family income. It was observed that the monthly family income of 38.2% families was taka [Bangladesh currency] 70 thousand and above but 79.1% children of these families were in underweight group [Table 7]. It was seen that prevalence of obesity was higher among the children of low-income group of families. The relationship was significant in the lower income group of families [χ2= 53.06 with p-value = 0.00]. The family income and food habit of the children and youth was significantly associated [Table 8, χ2= 94.76, p-value=0.00 It was seen that 47.9% children and youth took restaurant food. This percentage among the children and youth of higher income [70 thousand and above taka] group of families was 53.8.

Table 7: Distribution of children and adolescents according to their level of obesity and monthly family income.

Table 8: Distribution of children and adolescents according to their food habit and their family income [in 000 taka].

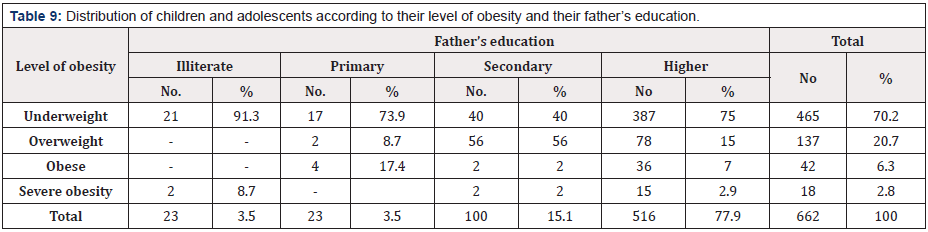

Table 9: Distribution of children and adolescents according to their level of obesity and their father’s education.

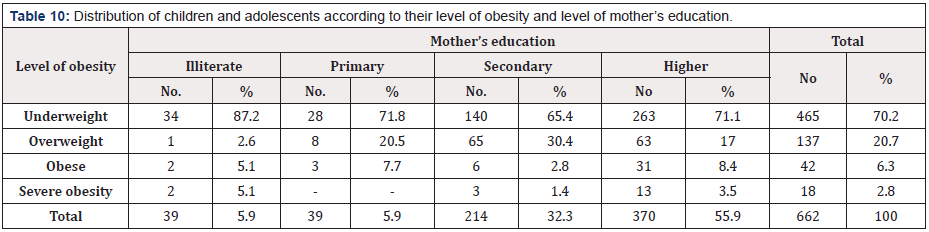

Table 10: Distribution of children and adolescents according to their level of obesity and level of mother’s education.

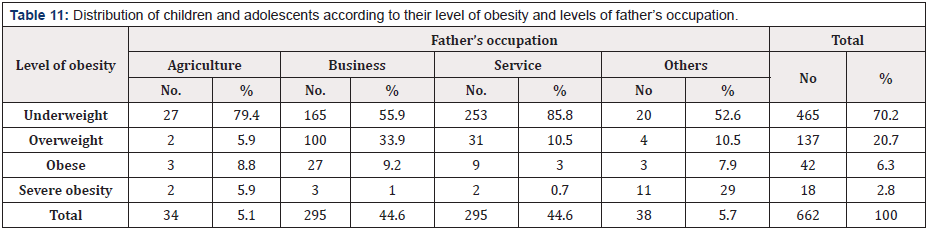

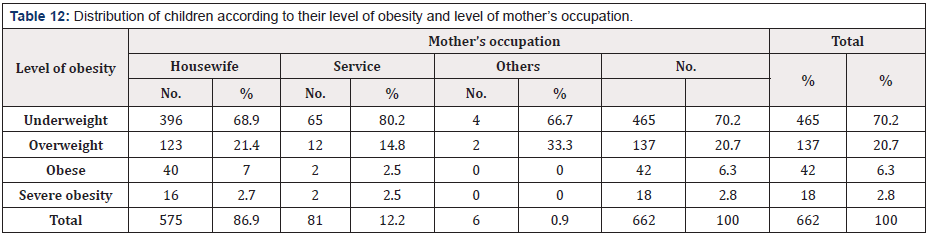

Family environment is one of the correlates of obesity among children [19]. It seemed that family environment is influenced by parents’ education and occupation. Let us investigate how fathers’ and mothers’ education were associated with children and adolescent’s obesity. It was seen that [Table 9] the fathers of 77.9 % children were highly educated and 75% children of them were underweight. The percentage of illiterate fathers was 3.5 and 91% children of these fathers are underweight. Both obesity and severe obesity among children of illiterate and primary educated fathers were more (8.7 and 17.4% respectively) compared to the children of secondary educated (2.1%) fathers. The differential in proportions of level of obesity and fathers’ educational level were highly significant [χ2= 111.70 with p-value = 0.00]. Similarly, significant differentials in proportions of obesity of children according to the differences of mothers’ education were also observed [Table 10, χ2= 39.23 with p-value = 0.00]. Significant differences in the level of obesity according to the variations in the levels of occupation of fathers (Table 11) were also observed [χ2= 186.02 with p-value = 0.00]. But mother’s occupation was not an influencing factor for the changes in the levels of obesity of children [(Table 11), χ2= 10. 50 with p-value = 0.572] (Table 12).

Results of Discriminant Analysis

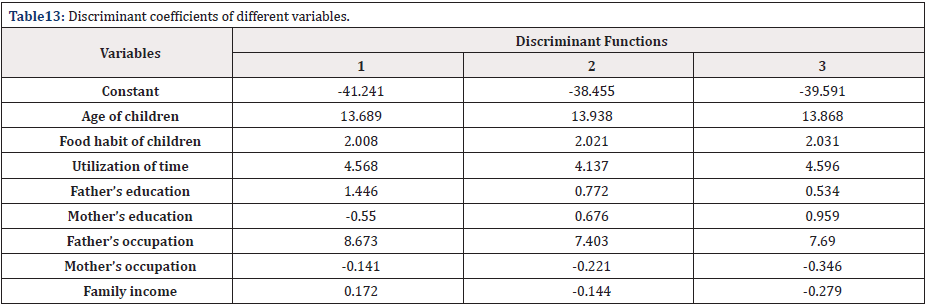

The children and adolescents are classified by their level of obesity. There are 4 groups of respondents and for these 4 groups the variables age of the children, food habit of children, utilization of time by the children, father’s education, mother’s education, father’s occupation, mother’s occupation and family income were different and most of them were associated with the level of obesity. Therefore, these variables were included to discriminate the children. For 4 groups of children 3 Fisher’s linear discriminant functions were available. The coefficients of these functions for different variables are shown in (Table 13).

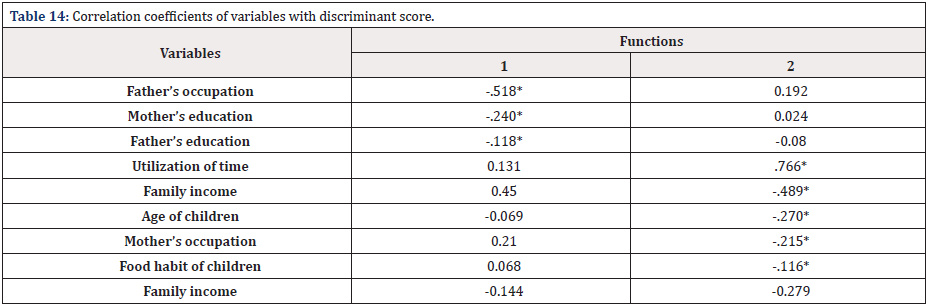

First function explains 92.7% variation of the children’s level of obesity and most important variable to explain this variation is father’s occupation followed by mother’s education and father’s education. This phenomenon is observed from pooled within groups correlations between discriminating variables and standardized canonical discriminant functions. The results of this pooled within groups correlations are given in Table 14. The most important variables identified by functions are shown by given asterix. Since first functions explains 92.7% variation in level of obesity and this function is statistically significant [ Wilk’s Lamda=0.834, Chi-square =97.811, p-value=0.000], the pooled within groups correlations are shown for this first function. Some variables are also found important by second function to discriminate children by level of obesity. However, the 2nd and 3rd functions are not statistically significant and the pooled within groups correlations of variables and 3rd function are not shown.

Discussion

In a cross-sectional study, it was observed that 81.4% students of the university under study [24] were living in urban area and fathers of around 46% students are highly educated. Almost similar was the case with mother’s education (90%). In respect of parent’s education and family income, the families of the students could be considered affluent. The present study was done using the data collected from similar type of affluent families. The data were collected from 560 randomly selected families. In these selected families, there were 662 children and youth These children were privileged group compared to the general children of the country. Our objective was to study the level of obesity among the children and adolescents of affluent families.

The study result showed that around 6.3% children were obese and 2.8% belonged to severe obese group. In a separate study [4] it was observed that the proportions of overweight are 2%, 11% and 15% among children of age under 15 years, 5-9 years and 10-18 years respectively in the Indian sub-continent [Bangladesh, India and Pakistan], the pooled estimate of obesity was around 6%. But these results were observed among all the children in the country The same percentage in Bangladesh was 7 [5]. The pooled estimate of proportion of obese and severe obese group of children and youth of affluent families was 9.1%. It indicated that obesity among children of affluent families was an alarming problem.

Fathers of most of the children and youth were engaged in respectable profession and higher proportion of them belonged to higher income group. Majority of the investigated children were males and higher proportion of them were underweight compared to the underweight group among female. As these children and adolescents belonged to affluent families, they had the scope to go to high socioeconomic school in which the expected facilities of physical education exist. But majority of the children were engaged in watching T.V. Very few children were involved in games and sports. Among the urban children risk of obesity was more compared to rural children. The percentage of obese children were lesser in rural area. This is an environmental effect on obesity as urban children spent less time for physical activity. Similar findings were observed in other studies. [18,21]. This study also indicated that the overweight and obesity were in increasing trend as rates of overweight were less in 2014 [5].

In a separate study [19] it was reported that the increasing trend of obesity was associated with fast food from restaurant. The present findings were also similar in respect of association of obesity and fast food from restaurants and visiting the fast food shops was associated with parent’s social status and family income. The offspring from affluent families visited fast food restaurants every now and then and obesity and severe obesity were particularly observed among them. Upward trend in parent’s education and family income were responsible factors for the children’s physical inactivity and their tendencies to watch T.V. and for visiting fast food shops. Discriminant analysis also showed that fathers’ occupation was the most responsible factor for obesity and overweight of children and youth followed by mothers’ education and fathers’ education. As a result, children of affluent families were becoming obese and finally were affected by diabetes. These are grave health hazards with significantly elevated risk of medical and psychological problems [9]. Thus, obesity and diabetes are interrelated phenomena, which can start at any time of life. In many instances’ obesity starts during childhood, unless proper care is not taken for the health of the children and youth.

Conclusion

The study was conducted among the children and adolescents of some randomly selected affluent [23,24] families of students of American International University, Bangladesh. Most of the children and adolescents were the city dwellers and parents of them were mostly highly educated and were in better economic and social conditions. The study indicated that obesity and severe obesity were significantly associated with parental social and economic status. Again, obesity and severe obesity were related to diabetes and many other non-communicable diseases [25,26]. These diseases are the major health burden in both developed and developing countries. In a separate study [2], it was reported that most of the NCDs affected people were suffering from diabetes. This is true for both children and adults. In this study also the prevalence rate of diabetes among the obese and severe obese groups of children and youth were observed higher (31.7%). This percentage was 21.9 among the underweight and overweight groups of children.

This is a problem for both parents and health planners. Parents can take care of foods of their offspring. They can choose school for their kids where there are enough facilities for child’s physical education. Government can introduce some regulations so that physical education is a compulsory co-curricular activity of the school. Urban parents should find time to accompany their kids to parks and playgrounds at least for some hours in a week. The urban children should be advised to go to the nearby school on foot accompanied by either of the parents or any of the family member. The school authority can encourage the children to take healthy foods which are available nearby school or they may be advised to bring healthy foods to take it during school hours. There should be prohibited regulations not to advertise fast food and candy for their children. Fresh and healthy foods along with physical activities may decrease the rate of obese children.

References

- Elizabeth R Pulgarom, Alam M Delameter (2014) Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes in Children, Epidemiology and Treatment. Curr Diab Rep 14(8): 508.

- Manu Raj, R Krishna Kumar (2010) Obesity in children and adolescents, Indian Jour. Medical Research 132(5): 598-607.

- Reilly JJ (2006) Obesity in childhood and adolescence: evidence based clinical and public health perspective. Post Graduate Medical Journal 82(969): 429-437.

- Biswas T, Islam A, Islam Md S, Pervin S, Rawal LB (2017) Overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in Bangladesh: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 142: 94-101.

- Hoque ME, Suhail AR Doli, Munim M, Kurt Long, Louis WN, et al. (2014) Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents of the Indian subcontinent: A meta-analysis approach. Nutrition Review 72(8): 541-550.

- Sinha R, Fisch G, Teague B, Tamborlane WV, Banya B, et al. (2002) Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance among children and adolescents with marked obesity. N Engl J Med 346(11): 802-810.

- Chris Wool Stem MS (2017) Type 2 Diabletes and Kids, The Growing Epidemic. Health Day.

- Weiss R, Dzuria J, Burgert TS, Tamborlane WV, Taksali SE, et al. (2004) Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 350(23): 2362-2374.

- Huang J, Gottschalk M, Norman G, Galfas K, Sallis J, et al. (2011) Compliance with behavioral guidelines for diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviors is related to insulin resistance among overweight and obese youth. BMC Res Notes 4: 29.

- Pulgaron ER (2013) Child obesity: a review of increased risk for physical and psychological combordities. Clin Ther 35A: A18-32.

- Goodman E, Whitaker RC (2002) A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity: Systematic Review. Int J Obesity 35.

- Schwimmer JB, Burnwinkle TM, Varni JW (2003) Health related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. J Am Med Assn 289(14): 1813-1819.

- Rolland Cachera MF, Dehgeer M, Maillot M, Bellisle F (2006) Early adiposity rebound: Causes and consequences for obesity in children and adults. Int J Obes 30 Suppl 4: S11-S17.

- Gortmaker SL, Must A, Perrin JM, et al. (1993) Social and economic consequences of overweight in adolescence and young adulthood. N Eng J Med 329(14): 1008-1012.

- Williams SM, Goulding A (2009) A patterns of growth associated with development of excessive fatness in children and adolescents: a review of prospective studies. Obes Rev 14(8): 645-658.

- Ketsantas P, Gaffney KF (2010) Risk profiles for overweight /obesity among preschools. Early Hum Dev 86(9): 563-568.

- Hendrie GA, Coveney J, Cox DN (2011) Defining the complexity of childhood obesity and related behavior within the family environment using structural equation modelling. Public Health Nutrition 15(1): 48-57.

- Elder JP, Arredondo EM, Campbell N, Baquero B, Duerksen S, et al. (2010) Individual, family, and community environmental correlates of obesity in Latino elementary school children. J Sch Health 80(1): 20-30.

- Epstien LH, Raja S, Daniel TO, Paluch RA, Wilfley DE, et al. (2012) The built environment moderate’s effects of family-based childhood obesity treatment over 2 years. Ann Behav Med 44(2): 248-258.

- Currie J, Della Vigna S, Moretti E, Vikram Pathania (2010) The effect of fast food restaurants on obesity and weight gain, Amer. Econ Jour Economic Policy 2: 32-63.

- Block JL, Macinko J (2008) Neighbourhoods and obesity. Nutr Rev 66(1): 2-20.

- Sallis JF, Zakarian JM, Hovell MF, Hofstetter R (1996) Ethnic, socioeconomic and sex differences in physical activity among adolescents. J Clin Epidemol 49(2): 125-134.

- Jannatul Fardus, Bhuyan KC (2016) Discriminating diabetic patients of some rural and urban areas of Bangladesh: A discriminant analysis approach. Euromediterrean Biom Jour 11(9): 134-140.

- Mahfuza K, Bhuyan KC (2014) Awareness of health hazard of tobacco consumption among students of American International University- Bangladesh. AJSE 13(1): 85-92.

- Bhuyan KC (2004) Multivariate analysis and its Applications. New Central Book Agency (Pvt) Ltd India.

- Ahmmed Md Mortuza, Bhuyan KC, Fardus J (2018) A study on identification of socioeconomic variables associated with non-communicable diseases among Bangladeshi adults. American Journal of Biomedical Science and Engineering 4(3): 24-29.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.