Mini Review

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Creative Commons, CC-BY

Heavy Metals in Cosmetics: The Notorious Daredevils and Burning Health Issues

*Corresponding author: Abdul Kader Mohiuddin, Department of Pharmacy, World University of Bangladesh, Bangladesh

Received: August 13, 2019 Published: August 20, 2019

DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.04.000829

Abstract

Personal care products and facial cosmetics are commonly used by millions of consumers on a daily basis. Direct application of cosmetics on human skin makes it vulnerable to a wide variety of ingredients. Despite the protecting role of skin against exogenous contaminants, some of the ingredients in cosmetic products are able to penetrate the skin and to produce systemic exposure. Consumers’ knowledge of the potential risks of the frequent application of cosmetic products should be improved. While regulations exist in most of the high-income countries, in low income countries there is a lack of similar standards. In most countries for which these legal regulations have been identified, restrictions on the permissible level of heavy metals are strict. There is a need for enforcement of existing rules, and rigorous assessment of the effectiveness of these regulations. The occurrence of metals in cosmetic products is of concern for three principal reasons:

a) The use of cosmetic products could represent a possible source of population-wide exposure daily, and often long-term exposure to metals in cosmetic products

b) Metals can accumulate in the body over time, and

c) A number of them are known to exhibit different chronic health effects, such as cancer, contact dermatitis, developmental, neurological and reproductive disorders, brittle hair and hair loss. Some metals are potent endocrine disruptors and respiratory toxins. Moreover, some metals, such as Cd, As, Pb, Hg and Sb, are exceptionally toxic with a wide variety of chronic health effects, whereas Cr, Ni and Co are well known skin sensitizers. Since the issue of heavy metals as deliberate cosmetic ingredients has been addressed, attention is turned to the presence of these substances as impurities.

Keywords: Heavy Metal Toxicity; Personal care products; Endocrine disruptors; Cosmetics Safety; Heavy Metal Contamination; Kohl; Cosmetic Regulation; Cosmetic Impurities

Abbreviations: CAGR: Compound Annual Growth Rate; ACD: Allergic Contact Dermatitis; CIR: Cosmetic Ingredient Review; T2DM: Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus; EWG: Environmental Working Group

Introduction

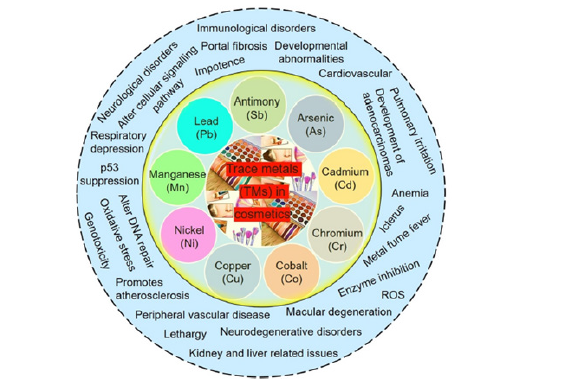

Cosmetics and personal care products are ubiquitous [1-3]. The US researchers identified some 12500 industrial chemicals used as cosmetic ingredients, includes carcinogens, pesticides, reproductive toxics, endocrine disruptors, plasticizers, degreasers, and surfactants [4-6]. The US FDA estimated 12,500 chemicals used in cosmetics, 20% of them are safe according to Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR) review, only 11 of them are banned in US but more than 1300 are banned or restricted in the EU [7-9]. Heavy metals such as lead, mercury, cadmium, arsenic and nickel, as well as aluminum, classified as a light metal, are detected in various types of cosmetics (color cosmetics, face and body care products, hair cosmetics, herbal cosmetics, etc.) [10]. The metals are from the contamination of raw materials and use of sub-standard raw materials, lack of compliance by small scale manufacturers, and lack of strict regulations [11]. Also, Alam et al. [12] says many cosmetic products contain heavy metals as ingredients or impurities [12]. Vella et al. [13] reported presence of lead in toothpastes were beyond limit of US and EU standards [13]. According to Panico et al. [14] PEGs (favorably used as penetration enhancers) may contain residual impurities like lead, iron, cobalt, nickel, cadmium, arsenic [14]. Łodyga-Chruścińska et al. [15] detailed nearness of lead and nickel in lipsticks and powders at level restricted by European guideline in Polish market [15] (Figure 1).

Applying kajal (otherwise called Kohl or Surma) to infants’ eyes is an old custom in numerous societies of the world including Asia, Middle East, European countries, North America and Africa. Kajal/ Surma has been reported to contain lead and to be a potential source of lead toxicity in children, which can lead to permanent damage to multiple organ systems [16-18]. A similar Nigerian cosmetic called ‘Tiro” applied to the infant’s eyelids contained 82.6% lead which was as high as 70% in Kajal or Surma [19,20]. Use of eye cosmetics imported from Pakistan was found to be strongly correlated with elevated blood lead levels [21]. Kohl, a type of customary cosmetic product used for eyeliner in the Middle East, contains more than 50% of lead [22]. A similar study with Malaysian eyeshadows shows the same, lead content exceeding limit of international standard [23]. It has been observed that the blood lead level of eye cosmetics consumers in Pakistan, India, and Saudi Arabia in comparison with non-consumers was threefold. Cd and Pb was profound among lipstick samples of Iran and were the most predominant in most Indian cosmetics, along with arsenic (As) [24-26]. Lip cosmetics to the digestive tract damages various vital organs once reaching into systemic circulation [1]. A similar study shows predominance of Hg and Pb among Indian herbal cosmetics exceeding WHO permissible limit. Very high level of trace metals was reported in locally produced facial makeup in Nigeria [1].

Figure 1:Several Untoward Effects Exerted by Heavy Metal Exposure from Cosmetics [1-3]. The global cosmetic products market was valued at USD 382.3 billion in 2010, 532.43 billion in 2017, and is expected to reach a market value of USD 805.61 billion by 2023, registering a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 7.14% during 2018-2023. Social media is key to the shift in consumer demand. Trends are shared more quickly and emotively, with celebrities and influencers-as well as everyday people-posting content which urges everyone to become a conscious consumer. The presence of heavy metals and xenobiotics are not normally considered as a primary concern in cosmetics. With many new products released into the market every season, it is hard to keep track of the safety of every product and some products may carry carcinogenic contaminants, while some others raise many more detrimental issues.

Cobalt is a skin allergen responsible for allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), found higher concentration in shampoo than relaxers and conditioners [28]. In individuals with tattoos containing red pigment of the starting point of mercuric sulfur (cinnabar-vermilion, Chinese red), they may encounter irritation that is restricted to this region inside a half year of tattooing [29]. Sindoor, a corrective powder utilized in Hindu religious and cultural ceremonies has hazardous degrees of lead [30]. The highest concentration of Pb was found in nettle, Cd in yarrow, and Hg in horsetail, plants most commonly used in herbal cosmetics of Poland [31]. Henna, a traditional plant product applied as temporary painton tattoos and hair dying, is reported to be very rich in heavy metals such as mercury and lead [32]. Saadatzadeh et al. [33] reported that arsenic contents of lipsticks, eye shadows, and eyebrow pencils was significantly higher than the BVL (Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety of Germany) standard [33]. Among the heavy metal impurities, mercury, arsenic, lead, cobalt, antimony, cadmium, nickel and chromium are exceptionally toxic and are prohibited in cosmetics to be included deliberately as ingredients in EU and US [34].

Pb were Cr are the most profound metals in talcum powder samples [35]. According to Health Canada, 100% of all cosmetics product tested positive for nickel and over 90% tested positive for both lead and beryllium and on the average contained at least 4 of the 8 metals of concern (arsenic, cadmium, lead, mercury, beryllium, nickel, selenium, and thallium) [36]. Although titanium’s use in sunscreens is regulated, some formulations also include other heavy metals, which are not regulated [37,38]. Cosmetics use in pregnancy is not uncommon. Schwalfenberg et al. [39] reported that prenatal lead exposure is associated with a greater risk of premature delivery, reduced postnatal growth, lower mental growth in childhood, schizophrenia and dementia in adulthood [39]. Even low level of Cd exposure may avert neurodevelopment [40]. Prenatal As exposure has been associated with low growth in utero, low birth weight, head and chest circumference in infants, inflammation and atherosclerotic disease in adults [41]. Also, Li et al. [41]reported that heavy metal exposure during fetal period of pregnancy may lead to intrauterine growth retardation [42].

Iron oxides are common colorants in eye shadows, blushes and concealers [43]. Some aluminum compounds are colorants in lip glosses, lipsticks and nail polishes [44]. Aluminum is also used in antiperspirants, sun creams and toothpaste. Chronic disorders currently discussed in connection with aluminum exposure: Alzheimer’s disease and breast cancer [45]. The safety assessment by CIR does not include metallic or elemental aluminum as a cosmetic ingredient [46]. Arsenic was known to be poisonous during the Victorian era, but perhaps some women thought that a little bit wouldn’t hurt [47]. In addition, some color additives may be contaminated by heavy metals like arsenic, lead and mercury [48]. Heavy metals may be intentionally added to detergents as preservatives, pigments (Pb), skin lightening, as well as antimicrobial agents (Hg) [49]. Significant level of As and Hg was reported with Mohammad et.al, 2017 in skin bleaching agents of Caribbean region [50] As used in skin cream and make-up powder causes skin problems, lung cancer, circulatory and peripheral neuropathy, and increased risk of gastrointestinal and urinary tract malignancies [51,52]. Several recent and older studies reported nephrotic syndrome from repeated exposure of mercury and other heavy metals from skin lightening agent [53,58].

Dental amalgam has been used as a restorative treatment in dentistry for well over 170 years. Even after the last mercury dental amalgam is placed, its toxic legacy will continue for decades, because of its pervasive bioaccumulation in the environment, as reported by Tibau et al. [9]. However, mercury is usually added to skin-lightening products due to its whitening effect. Mercury ions replace tyrosinase enzyme anions, which inhibit the formation of melanin and produce the whitening and anti-freckle effects [60]. Sun et al. [61] reported that chronic mercury poisoning is associated with irritability, tremor, gingivitis, memory loss, dizziness, insomnia, edema, proteinuria, abdominal pain, nausea, hyperthyroidism, and abortion [61]. Wang et al. [62] suggested that cumulative exposure to heavy metals as mixtures is associated with obesity and its related chronic conditions such as hypertension and T2DM [62]. Lead poisoning leads to anemia due to jeopardized heme synthesis and acts as a potent reversible and selective blocker of voltage-dependent calcium channels at low concentrations [63,64]. Severe damage to the brain and kidneys, both in adults and children, were found to be linked to exposure to heavy lead levels resulting in death [62-65]. In pregnant women, high exposure to lead may cause miscarriage [76-81]. Men exposed to lead mainly from hair colorants [82-85].

Chronic lead exposure was found to reduce fertility in males [86-89]. The 2017 US FDA safety recall to discontinue using Magellan Diagnostics’ Lead-Care Testing Systems for analyzing venous blood samples also highlighted the need for improved blood lead testing and surveillance [90]. Ettinger et al. [91] reported that economic benefit of lowering lead levels among children by preventing lead exposure has been estimated at $213 billion per year [91]. Childhood lead poisoning prevention programs can effectively utilize Medicaid data to increase testing and improve blood lead surveillance [92]. Various sources of acquaintance to chromium exist; including lipstick, eye pencil, eyeliner, eyeshadow, and makeup powder [93,94]. Cr exists in two valence states, and both oxidation states, i.e. Cr3+ and Cr6+ can act as potential haptens causing ACD and skin ulcers [95,99]. Chromium ACD can be a chronic debilitating disease, perhaps because chromium is difficult to avoid. Toxic metals (cadmium, cobalt, copper, nickel and. lead) from body cream basically moisturizers and skin-lightening (toning/bleaching) creams [100]. An increase in level of cadmium has been reported to inhibit DNA repair including mismatch, base excision, and nucleotide excision [101]. Zinc oxide (ZnO), an inorganic compound that appears as a white powder, is used frequently as an ingredient in sunscreens [102].

Zinc has been reported to cause the same signs of illness as does lead, and can easily be mistakenly diagnosed as lead poisoning [103]. Excess zinc exposure may induce toxic effects on the hematopoietic system, biochemistry and endocrine system function [104]. Skin care experts in the US reckon copper will be this decade’s most prominent anti-aging ingredient [105]. Copper delivery through skin can provide beneficial effects but its potential to induce skin irritation reactions is often overlooked [106]. Cobalt and nickel metals commonly found in lipstick, eyeshadow, face paint and hair cream associated with contact dermatitis. Cobalt and its salts are widely used as coloring agents in makeup and light-brown hair dyes [31]. Nickel compound exposure can lead to nephrotoxicity, skin irritation and hypersensitivity [107]. Cobalt chloride has a hazard rank of 9 in the Environmental Working Group (EWG) Skin Deep Database and is banned for use in cosmetics by the EU. Since cobalt and nickel are almost always found together, it is wise to avoid both metals [108]. Literature data show that in commercially available cosmetics have potentially toxic metals that may cause danger to human health. This is coupled with prolonged duration of contact, which may occur due to repeated use of the products. There’s an old saying that “A thing of beauty is joy forever”. But it should be imparted through avoiding beasts inside the beautification.

Acknowledgement

I’m thankful to Dr. Alessandra Panico, Department of Biological and Environmental Science and Technology, University of Salento, Lecce, Italy for her valuable time to audit my paper and for her thoughtful suggestions. I’m also grateful to seminar library of Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Dhaka and BANSDOC Library, Bangladesh for providing me books, journal and newsletters.

References

- Bilal M, Iqbal HMN (2019) An insight into toxicity and human-health-related adverse consequences of cosmeceuticals - A review. Sci Total Environ 670: 555-568.

- Bakr RO, Amer RI, Fayed MAA, Ragab TIM. (2019) A Completely Polyherbal Conditioning and Antioxidant Shampoo: A Phytochemical Study and Pharmaceutical Evaluation. J Pharm Bioallied Sci (2): 105-115.

- Reuters (2018) Global Cosmetics Products Market expected to reach USD 805.61 billion by 2023-Industry Size & Share Analysis. Featured News.

- Zanolli L (2019) Pretty hurts: are chemicals in beauty products making us ill? The Guardian.

- Sheikh AG (2018) Harmful effects of beauty care products on human health. Int J Med Sci Public Health 7(1): 1-8.

- Navid N (2014) The Perils of Cosmetics. J Pharm Sci & Res 6(10): 338- 341.

- St. Pierre B. Safe cosmetics: What’s in your bathroom cabinet?

- Milman O (2019) US cosmetics are full of chemicals banned by Europe – why? The Guardian.

- Anne Houtman SKAJI (2013) Toxic bottles? On the trail of chemicals in our everyday lives. In: Correa J (Ed.) American Environmental Science for a Changing World. Kate Ahr Paker p. 54.

- Ahsan H (2019) The biomolecules of beauty: biochemical pharmacology and immunotoxicology of cosmeceuticals. J Immunoassay Immunochem 40(1): 91-108.

- Omenka SS, Adeyi AA (2016) Heavy metal content of selected personal care products (PCPs) available in Ibadan, Nigeria and their toxic effects. Toxicol Rep 3: 628-635.

- Alam MF, Akhter M, Mazumder B, ferdous A, Hossain MD, et al. (2019) Assessment of some heavy metals in selected cosmetics commonly used in Bangladesh and human health risk. J Anal Sci Technol 10(2): 1-8.

- Vella A, Attard E (2019) Analysis of Heavy Metal Content in Conventional and Herbal Toothpastes Available at Maltese Pharmacies. Cosmetics 6(2): 28.

- Chruścińska EL, Sykuła A, Więdłocha M (2018) Hidden Metals in Several Brands of Lipstick and Face Powder Present on Polish Market. Cosmetics 5(4): 57.

- Panico A, Serio F, Bagordo F, Grassi T, Idolo A, et al. (2019) Skin safety and health prevention: an overview of chemicals in cosmetic products. J Prev Med Hyg 60(1): E50-E57.

- Khan F (2019) Is surma safe for newborn eyes? Daily Times.

- McMichael JR, Stoff BK (2018) Surma eye cosmetic in Afghanistan: a potential source of lead toxicity in children. Eur J Pediatr 177(2): 265-268.

- De Caluwé JP (2009) Lead poisoning caused by prolonged use of kohl, an underestimated cause in French-speaking countries. J Fr Ophtalmol 32(7): 459-463.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012) Infant lead poisoning associated with use of tiro, an eye cosmetic from Nigeria--Boston, Massachusetts, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 61(30): 574-576.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2013) Childhood lead exposure associated with the use of kajal, an eye cosmetic from Afghanistan- Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 62(46): 917-9.

- Sprinkle RV (1995) Leaded eye cosmetics: a cultural cause of elevated lead levels in children. J Fam Pract 40(4): 358-62.

- Massadeh AM, El-Khateeb MY, Ibrahim SM (2017) Evaluation of Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, and Pb in selected cosmetic products from Jordanian, Sudanese, and Syrian markets. Public Health 149: 130-137.

- Lim JS, Ho YB, Hamsan H (2017) Heavy metals contamination in eye shadows sold in Malaysia and user’s potential health risks. Ann Trop Med Public Health 10: 56-64.

- Nourmoradi H, Foroghi M, Farhadkhani M, Vahid Dastjerdi M (2013) Assessment of lead and cadmium levels in frequently used cosmetic products in Iran. J Environ Public Health 962727.

- Salama AK (2015) Assessment of metals in cosmetics commonly used in Saudi Arabia. Environ Monit Assess 188(10): 553.

- Alqadami AA, Abdalla MA, AlOthman ZA, Omer K (2013) Application of solid phase extraction on multiwalled carbon nanotubes of some heavy metal ions to analysis of skin whitening cosmetics using ICP-AES. Int J Environ Res Public Health 10(1): 361-374.

- Sani A, Gaya MB, Abubakar FA (2016) Determination of some heavy metals in selected cosmetic products sold in kano metropolis, Nigeria. Toxicol Rep 3: 866-869.

- Iwegbue CMA, Emakunu OS, Obi G, Nwajei GE, Martincigh BS (2016) Evaluation of human exposure to metals from some commonly used hair care products in Nigeria. Toxicol Rep 3: 796-803.

- Unsal V (2018) Natural Phytotherapeutic Antioxidants in the Treatment of Mercury Intoxication-A Review. Adv Pharm Bull. 8(3): 365-376.

- Shah MP, Shendell DG, Strickland PO, Bogden JD, Kemp FW, et al. (2017 ) Lead Content of Sindoor, a Hindu Religious Powder and Cosmetic: New Jersey and India, 2014-2015. Am J Public Health 107(10): 1630-1632.

- Fischer A, Brodziak-Dopierała B, Loska K, Stojko J (2017) The Assessment of Toxic Metals in Plants Used in Cosmetics and Cosmetology. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(10).

- Alissa EM, Ferns GA (2011) Heavy metal poisoning and cardiovascular disease. J Toxicol 870125.

- Saadatzadeh A, Afzalan S, Zadehdabagh R, Tishezan L, Najafi N, et al. (2019) Determination of heavy metals (lead, cadmium, arsenic, and mercury) in authorized and unauthorized cosmetics. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 38(3): 207-211.

- SCOOPWHOOP (2017) Not Just Virat Kohli, Here Are Other Celebs Who Said No to Endorsements On Ethical Grounds.

- Gondal MA, Dastageer MA, Naqvi AA, Isab AA, Maganda YW (2012) Detection of toxic metals (lead and chromium) in talcum powder using laser induced breakdown spectroscopy. Appl Opt 51(30): 7395-401.

- Orisakwe OE, Otaraku JO (2013) Metal concentrations in cosmetics commonly used in Nigeria. Scientific World Journal 5: 959637.

- Aldayel O, Hefne J, Alharbi KN, Al-Ajyan T (2018) Heavy Metals Concentration in Facial Cosmetics. Nat Prod Chem Res 6: 303.

- Capelli C, Foppiano D, Venturelli G, Carlini E, Magi E, et al. (2014) Determination of Arsenic, Cadmium, Cobalt, Chromium, Nickel, and Lead in Cosmetic Face-Powders: Optimization of Extraction and Validation. Analytical Letters 47: 7.

- Schwalfenberg G, Rodushkin I, Genuis SJ (2018) Heavy metal contamination of prenatal vitamins. Toxicol Rep 5: 390-395.

- Wang Y, Chen L, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Wang C, et al. (2016) Effects of prenatal exposure to cadmium on neurodevelopment of infants in Shandong, China. Environ Pollut 211: 67-73.

- Claus Henn B, Ettinger AS, Hopkins MR, Jim R, Amarasiriwardena C, et al. (2016) Prenatal Arsenic Exposure and Birth Outcomes among a Population Residing near a Mining Related Superfund Site. Environ Health Perspect 124(8): 1308-1315.

- Li H, Zheng J, Wang H, Huang G, Huang Q, et al. (2019) Maternal cosmetics use during pregnancy and risks of adverse outcomes: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 9(1): 8030.

- Bruzzoniti MC, Abollino O, Pazzi M, Rivoira L, Giacomino A, et al. (2017) Chromium, nickel, and cobalt in cosmetic matrices: an integrated bioanalytical characterization through total content, bioaccessibility, and Cr (III)/Cr (VI) speciation. Anal Bioanal Chem 409(29): 6831-6841.

- Brown VJ (2013) Metals in lip products: a cause for concern? Environ Health Perspect 121(6): A196.

- Klotz K, Weistenhöfer W, Neff F, Hartwig A, Van Thriel C, et al. (2017) The Health Effects of Aluminum Exposure. Dtsch Arztebl Int 114(39): 653-659.

- Becker LC, Boyer I, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, Hill RA, et al. (2016) Safety Assessment of Alumina and Aluminum Hydroxide as Used in Cosmetics. Int J Toxicol 35(3 suppl): 16S-33S.

- Mohiuddin AK (2019) Cosmetics in use: a pharmacological review. J Dermat Cosmetol 3(2): 50-67.

- Ajaezi GC, Amadi CN, Ekhator OC, Igbiri S, Orisakwe OE (2018) Cosmetic Use in Nigeria May Be Safe: A Human Health Risk Assessment of Metals and Metalloids in Some Common Brands. J Cosmet Sci 69(6): 429-445.

- Alizadeh A, Balali Mood M, Mahdizadeh A, Riahi Zanjani B (2017) Mercury and Lead Levels in Common Soaps from Local Markets in Mashhad, Iran. IJT 11(4): 1-3.

- Mohammed T, Mohammed E, Bascombe S (2017) The evaluation of total mercury and arsenic in skin bleaching creams commonly used in Trinidad and Tobago and their potential risk to the people of the Caribbean. J Public Health Res 6(3): 1097.

- Sneyers L, Verheyen L, Vermaercke P, Bruggemann M (2009) Trace element determination in beauty products by k0-instrumental neutron activation analysis. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 281: 259-263.

- Lavilla I, Cabaleiro N, Costas M, de la Calle I, Bendicho C (2009) Ultrasound- assisted emulsification of cosmetic samples prior to elemental analysis by different atomic spectrometric techniques. Talanta 80(1): 109-116.

- Chan TYK, Chan APL, Tang HL (2019) Nephrotic syndrome caused by exposures to skin-lightening cosmetic products containing inorganic mercury. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 17: 1-7.

- Qin AB, Su T, Wang SX, Zhang F, Zhou FD, et al. (2019) Mercury-associated glomerulonephritis: a retrospective study of 35 cases in a single Chinese center. BMC Nephrol 20(1): 228.

- Doshi M, Annigeri RA, Kowdle PC, Subba Rao B, Varman M (2018) Membranous nephropathy due to chronic mercury poisoning from traditional Indian medicines: report of five cases. Clin Kidney J 12(2): 239-244.

- Zhang L, Liu F, Peng Y, Sun L, Chen C (2014) Nephrotic syndrome of minimal change disease following exposure to mercury-containing skin-lightening cream. Ann Saudi Med 34(3): 257-261.

- Díaz Gacía JD, Arceo E (2018) Rev Colomb Nefrol 5(1): 43-53.

- Orr SE, Bridges CC (2017) Chronic Kidney Disease and Exposure to Nephrotoxic Metals. Int J Mol Sci 18(5): E1039.

- Tibau AV, Grube BD (2019) Mercury Contamination from Dental Amalgam. J Health Pollut 9(22): 190612.

- Mohiuddin AK (2019) Skin Lighteners & Hyperpigmentation Management. ASIO Journal of Pharmaceutical & Herbal Medicines Research (ASIO-JPHMR) 5(1).

- Sun GF, Hu WT, Yuan ZH, Zhang BA, Lu H (2017) Characteristics of Mercury Intoxication Induced by Skin-lightening Products. Chin Med J (Engl) 130(24): 3003-3004.

- Wang X, Mukherjee B, Park SK (2018) Associations of cumulative exposure to heavy metal mixtures with obesity and its comorbidities among U.S. adults in NHANES 2003-2014. Environ Int 121(Pt 1): 683-694.

- Wani AL, Ara A, Usmani JA (2015) Lead toxicity: a review. Interdiscip Toxicol 8(2): 55-64.

- Assi MA, Hezmee MN, Haron AW, Sabri MY, Rajion MA (2016) The detrimental effects of lead on human and animal health. Vet World 9(6): 660-671.

- Sanders T, Liu Y, Buchner V, Tchounwou PB (2009) Neurotoxic effects and biomarkers of lead exposure: a review. Rev Environ Health 24(1): 15-45.

- Cecil KM, Brubaker CJ, Adler CM, Dietrich KN, Altaye M, et al. (2008) Decreased brain volume in adults with childhood lead exposure. PLoS Med 5(5): e112.

- Mason LH, Harp JP, Han DY (2014) Pb neurotoxicity: neuropsychological effects of lead toxicity. Biomed Res Int 2014: 840547.

- Kim HC, Jang TW, Chae HJ, Choi WJ, Ha MN, et al. (2015) Evaluation and management of lead exposure. Ann Occup Environ Med 27: 30.

- Stewart WF, Schwartz BS (2007) Effects of lead on the adult brain: a 15- year exploration. Am J Ind Med 50(10): 729-739.

- Liu KS, Hao JH, Zeng Y, Dai FC, Gu PQ (2013) Neurotoxicity and biomarkers of lead exposure: a review. Chin Med Sci J 28(3): 178-188.

- Kwon SY, Bae ON, Noh JY, Kim K, Kang S, et al. (2015) Erythrophagocytosis of lead-exposed erythrocytes by renal tubular cells: possible role in lead-induced nephrotoxicity. Environ Health Perspect 123(2): 120-127.

- Hauptman M, Bruccoleri R, Woolf AD (2017) An Update on Childhood Lead Poisoning. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 18(3): 181-192.

- Rana MN, Tangpong J, Rahman MM (2018) Toxicodynamics of Lead, Cadmium, Mercury and Arsenic-induced kidney toxicity and treatment strategy: A mini review. Toxicol Rep 5: 704-713.

- Vivek B Kute, Jigar D shrimali, Manish R Balwani, Umesh R Godhani, Aruna V Vanikar, et al. (2013) Lead nephropathy due to Sindoor in India. Renal Failure 35(6): 885-887.

- Reilly R, Spalding S, Walsh B, Wainer J, Pickens S, et al. (2018) Chronic Environmental and Occupational Lead Exposure and Kidney Function among African Americans: Dallas Lead Project II. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(12): E2875.

- Cleveland LM, Minter ML, Cobb KA, Scott AA, German VF (2008) Lead hazards for pregnant women and children: part 1: immigrants and the poor shoulder most of the burden of lead exposure in this country. Part 1 of a two-part article details how exposure happens, whom it affects, and the harm it can do. Am J Nurs 108(10): 40-49.

- Bakhireva LN, Rowland AS, Young BN, Cano S, Phelan ST, et al. (2013) Sources of potential lead exposure among pregnant women in New Mexico. Matern Child Health J 17(1): 172-179.

- Vigeh M, Yokoyama K, Kitamura F, Afshinrokh M, Beygi A, et al. (2010) Early pregnancy blood lead and spontaneous abortion. Women Health 50(8): 756-766.

- Taylor CM, Golding J, Emond AM (2015) Adverse effects of maternal lead levels on birth outcomes in the ALSPAC study: a prospective birth cohort study. BJOG 122(3): 322-328.

- Jameil NA (2014) Maternal serum lead levels and risk of preeclampsia in pregnant women: a cohort study in a maternity hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7(6): 3182-3189.

- Riess ML, Halm JK (2007) Lead poisoning in an adult: lead mobilization by pregnancy? J Gen Intern Med 22(8): 1212-1215.

- Marzulli FN, Watlington PM, Maibach HI (1978) Exploratory skin penetration findings relating to the use of lead acetate hair dyes. Hair as a test tissue for monitoring uptake of systemic lead. Curr Probl Dermatol 7: 196-204.

- Liu B, Jin SF, Li HC, Sun XY, Yan SQ, et al. (2019) The Bio-Safety Concerns of Three Domestic Temporary Hair Dye Molecules: Fuchsin Basic, Victoria Blue B and Basic Red 2. Molecules 24(9): E1744.

- Sampathkumar K, Yesudas S (2009) Hair dye poisoning and the developing world. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2(2): 129-131

- Saitta P, Cook CE, Messina JL, Brancaccio R, Wu BC, et al. (2013) Is there a true concern regarding the use of hair dye and malignancy development?: a review of the epidemiological evidence relating personal hair dye use to the risk of malignancy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 6(1): 39-46.

- Vigeh M, Smith DR, Hsu PC (2011) How does lead induce male infertility? Iran J Reprod Med. Winter 9(1): 1-8.

- Wu HM, Lin Tan DT, Wang ML, Huang HY, Lee CL, et al. (2012) Lead level in seminal plasma may affect semen quality for men without occupational exposure to lead. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 10: 91.

- Rehman S, Usman Z, Rehman S, Al Draihem M, Rehman N, et al. (2018) Endocrine disrupting chemicals and impact on male reproductive health. Transl Androl Urol 7(3): 490-503.

- Flora G, Gupta D, Tiwari A (2012) Toxicity of lead: A review with recent updates. Interdiscip Toxicol 5(2): 47-58.

- Ettinger AS, Ruckart PZ, Dignam T (2019) Lead Poisoning Prevention: The Unfinished Agenda. J Public Health Manag Pract 25(Suppl 1), Lead Poisoning Prevention: S1-S2.

- Ettinger AS, Leonard ML, Mason J (2019) CDC’s Lead Poisoning Prevention Program: A Long-standing Responsibility and Commitment to Protect Children from Lead Exposure. J Public Health Manag Pract 25 Suppl 1, Lead Poisoning Prevention: S5-S12.

- Bruce SA, Christensen KY, Coons MJ, Havlena JA, Meiman JG, et al. (2019) Using Medicaid Data to Improve Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program Outcomes and Blood Lead Surveillance. J Public Health Manag Pract 25 Suppl 1, Lead Poisoning Prevention: S51-S57.

- Gondal MA, Seddigi ZS, Nasr MM, Gondal B (2010) Spectroscopic detection of health hazardous contaminants in lipstick using Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. J Hazard Mater 175(1-3): 726-732.

- Lim DS, Roh TH, Kim MK, Kwon YC, Choi SM, et al. (2018) Non-cancer, cancer, and dermal sensitization risk assessment of heavy metals in cosmetics. J Toxicol Environ Health A 81(11): 432-452.

- Hwang M, Yoon EK, Kim JY, Son BK, Yang SJ, et al. (2009) Safety assessment of chromium by exposure from cosmetic products. Arch Pharm Res 32(2): 235-241.

- Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Menné T (2007) Contact allergy epidemics and their controls. Contact Dermatitis 56(4): 185-195.

- Kang EK, Lee S, Park JH, Joo KM, Jeong HJ, et al. (2006) Determination of hexavalent chromium in cosmetic products by ion chromatography and postcolumn derivatization. Contact Dermatitis 54(5): 244-248.

- Wilbur S, Abadin H, Fay M, Yu D, Tencza B, et al. (2012) Toxicological Profile for Chromium. Atlanta (GA): Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US) health effects.

- Shelnutt SR, Goad P, Belsito DV (2007) Dermatological toxicity of hexavalent chromium. Crit Rev Toxicol 37(5): 375-387.

- OC Theresa, OC Onebunne, WA Dorcas, OI Ajani (2011) Potentially toxic metals exposure from body creams sold in Lagos, Nigeria. Researcher 3(1): 30-37.

- Chen QY, DesMarais T, Costa M (2019) Metals and Mechanisms of Carcinogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 59: 537-554.

- Kim KB, Kim YW, Lim SK, Roh TH, Bang DY, et al. (2017) Risk assessment of zinc oxide, a cosmetic ingredient used as a UV filter of sunscreens. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 20(3): 155-182.

- Martin CJ, Werntz CL 3rd, Ducatman AM (2004) The interpretation of zinc protoporphyrin changes in lead intoxication: a case report and review of the literature. Occup Med (Lond) 54(8): 587-591.

- Piao F, Yokoyama K, Ma N, Yamauchi T (2003) Subacute toxic effects of zinc on various tissues and organs of rats. Toxicol Lett 145(1): 28-35.

- Yeomans M (2014) Copper-the anti-aging ingredient of this decade? Cosmetics Design (USA).

- Li H, Toh PZ, Tan JY, Zin MT, Lee CY, et al. (2016) Selected Biomarkers Revealed Potential Skin Toxicity Caused by Certain Copper Compounds. Sci Rep 6: 37664.

- Magaye RR, Yue X, Zou B, Shi H, Yu H, et al. (2014) Acute toxicity of nickel nanoparticles in rats after intravenous injection. Int J Nanomedicine 9:1393-1402.

- Thompson L Cobalt in Cosmetics: Is it safe?

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.